Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus (Cristoforo Colombo, in Italian, or Christophorus Columbus, in Latin; of disputed origins, experts favor Genoa, Republic of Genoa where he may have been born on October 31, 1451 and is known to have died in Valladolid on May 20, 1506) was a navigator, cartographer, admiral, viceroy, and Governor-General of the West Indies serving of the Crown of Castile. He made the so-called discovery of America on October 12, 1492, upon reaching the island of Guanahani, in the Bahamas.

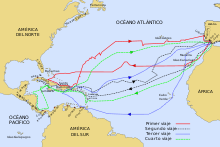

He made four trips to the Indies —the initial name of the American continent— and although he was possibly not the first European explorer of America, he is considered the discoverer of a new continent —for this reason called the New World— for Europe, being the first to chart a round-trip route across the Atlantic Ocean and break the news. This fact decisively promoted the worldwide expansion of European civilization, as well as the conquest and colonization of the American continent by several of its powers. It is not known for sure to what extent he was aware that the Americas were a totally separate land mass; he never clearly renounced his belief that he had reached the Far East.

As colonial governor, Columbus was accused by his contemporaries of significant brutality and was soon removed from office. During his government in Hispaniola, the Taínos, a people who were decimated and not counted in the censuses of the time but of whom descendants remain, were subject to a tax, distributed among the colonists and sold as slaves. The accusations of genocide made against him by others have been denied by some historians. Columbus's strained relations with the Crown of Castile and its appointed colonial administrators in the Americas led to his arrest and expulsion from Hispaniola in 1500, and subsequently to a protracted dispute over the benefits he and his heirs claimed were owed by the crown.

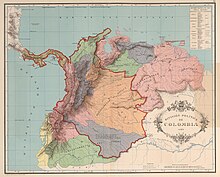

His anthroponym is a global icon that inspired various names, such as that of a country: Colombia, and two regions of North America: British Columbia, in Canada, and the District of Columbia, in the United States.

Historical profile

Christopher Columbus argued that the Far East (known at the time as "Las Indias") could be reached from Europe by sailing west across the Atlantic Ocean, and that it was possible to make the voyage by sea with a chance of success. The fall of the Eastern Roman Empire into the hands of the Ottoman Turks in 1453, after the capture of Constantinople, its capital, caused the cost of trade between Europe and the eastern regions.

Although in the iii century B.C. C., the Greek astronomer Eratosthenes had calculated the measurement of the Earth's circumference quite accurately, apparently Columbus's hypothesis about the possibility of the trip was based on alternative (and erroneous) calculations about the size of the sphere, since which he supposed was smaller than it really is. Now, Columbus claimed that he had collected data on the existence of inhabited lands on the other side of the Atlantic. From them he deduced that the eastern end of Asia was much closer to Europe than the cosmographers of the time supposed. It was also possible that such reports testified to the presence of islands that could serve as stopovers on a voyage to the Indies.

Other theories maintain that Columbus had heard data, through the gossip of sailors, about the existence of lands much closer to Europe than Asia was scientifically supposed to be, and that he undertook the task of reaching it to trade without depending on the Republic of Genoa or the Kingdom of Portugal. One of them, known as the prenaut theory, suggests that during the time Columbus spent on the Portuguese islands in the Atlantic he took care of a dying Portuguese or Castilian sailor whose caravel had been swept away by currents. from the Gulf of Guinea to the Caribbean Sea. Some authors even say that it could be Alonso Sánchez de Huelva, although according to other sources it could be Portuguese or Biscayan. This theory suggests that the prenaut confided the secret to Columbus. Some scholars believe that the strongest evidence in favor of this theory is the Capitulations of Santa Fe, since they speak of "what he has discovered in the oceanic seas" while granting Columbus a series of privileges not granted until then no one.

What is certain is that Columbus not only managed to reach the shores of America, but also returned to Europe, making a total of four voyages and creating a periodic and safe navigation route between Europe and America. Although it is known that the Siberians had arrived in America in the Pleistocene, and that there is documentation that talks about possible previous trips made by the Carthaginians, Andalusian Muslims, Vikings, Chinese and Polynesians. However, it is from the Columbus' voyages, and other explorers and conquerors that followed him, when permanent links were established with Europe and one can speak of a "discovery", as there was recognition of the nations involved and verifiable testimonies at the time. From this "meeting" some European powers invaded American territory, imposing their political, cultural and religious dominance over local cultures.

Columbus planned his voyage in order to bring merchandise from the East, especially spices and gold. The path of spices, which included spices, silk and other products originating from the Far East, had arrived through the centuries always along the commercial route that crossed Asia to Europe, through Asia Minor and Egypt, but after the expansion of the Ottoman Empire this route became difficult and was monopolized by them and their partners, the Italian merchants. The Kingdom of Portugal and the Kingdom of Castile, at that time the first States of the Modern Age, wanted these goods without intermediaries.

Because the Portuguese had achieved their Reconquista against the Muslims in the 13th century, they took the lead in the competition to reach a new route of the spice industry that was a direct maritime alternative to East Asia. Portugal launched to navigate the ocean sea bordering Africa and granting itself the monopoly of said navigation through the Atlantic Ocean with the exception of the Canary Islands. In 1488 the navigator Bartolomé Díaz found the way through the Cape of Good Hope, which linked the Atlantic Ocean with the Indian Ocean.

For its part, the Kingdom of Castile, in the same year that it successfully completed its Reconquest, searched for a new spice route, and although it also searched for it in the Atlantic Ocean, it set another course —to the west — in waters far from the coast and unknown to mariners.

The arrival of Columbus in America allowed the development of trade and the shipment to Europe of a large amount of food that was grown in those lands, such as corn, potatoes, cocoa, tobacco, peppers, pumpkins, pumpkin, tomato, beans (new varieties of beans), avocado and vanilla, among others, which were quickly adopted by Europeans and the rest of the world. Researchers have estimated that three-fifths of the world's current crops were imported from the Americas. Conversely, the Columbian expedition later brought the wheel, the iron, the horse, the pig, the donkey to America., coffee, sugar cane and firearms, among others.

On his first voyage, the navigator reached the island of San Salvador, called Guanahani by the inhabitants they encountered, in what is now the Bahamas. After two months of voyage, later visiting Cuba and Hispaniola, he returned to Spain seven months after his departure. On his last trip, it only took him a month and four days to reach the shores of America.

Origin

The consensus among experts on the birthplace of Christopher Columbus is that he was born in the Republic of Genoa. Alternative theories of his origin have been generally rejected by mainstream experts.

The majority supported thesis maintains that Cristoforo Colombo was born in 1451 in Savona, in the Republic of Genoa, although recent research estimates, on the contrary, that he was born in 1446. His parents would be Doménico Colombo —master weaver and later merchant— and Susanna Fontanarossa. Of the five children of the marriage, two, Cristoforo and Bartolomeo, soon had a seafaring vocation. The third was Giacomo, who learned the weaver's trade. Regarding the remaining two, Giovanni died young and the only woman left no trace. There are notarial and judicial acts, such as the mentioned will of his son where he affirms his father's Genoese origin, which defend this thesis. In addition, the Columbus himself declares to be Genoese, in the document called Fundación de Mayorazgo he mentions "I came out of it and was born there [in Génova]", but various authors and researchers indicate that this statement would probably be interested for the Columbian Lawsuits that his descendants maintained with the crown of Castile, and for this reason they declared it false or apocryphal; however, other researchers at the beginning of the xx century found documentation in the Simancas Archive that, according to them, showed the authenticity of this statement. Said document was found in 1925 and contained all the pertinent signatures and seals, which were validated by a special commission that ratified the credibility of the document issued on September 28, 1501. There is also a letter from Pedro de Ayala, ambassador of the Reyes Católicos in England, where he affirms that Juan Caboto, who proposed to explore the Atlantic for England, was "another Genoese like Columbus". In addition, the municipal authorities of Genoa showed, between 1931 and 1932, reliable records that affirmed its Genoese origin.

Another Genoese hypothesis is that Christopher Columbus was born in Cogoleto.

Secondary Hypotheses

Secondary theories affirm that the origin of Christopher Columbus is an enigma on which there is no unanimity among historians and researchers, among other reasons due to confusion and loss of documentation regarding his origins and ancestry. In addition, his own son, Hernando Colón, in his History of Admiral Don Cristóbal Colón, further obscured his place of birth, stating that his father did not want his origin and homeland to be known. Among other reasons, multiple theories have arisen about the birthplace of Columbus, although there is a reliable will in which Hernando Colón himself asserts that his father was a Genoese: "son of Christopher Columbus, Genoese, first admiral to discover the Indies". Some authors and researchers have defended other hypotheses about the possible origins of Columbus and the reasons why he wanted to hide them.

Jewish hypothesis

Several historians and authors have argued that Columbus was of Sephardic origin. Among others, The Enigma of Columbus includes the interpretation made by Cecil Roth of the initials S.A.S noted by Columbus in his confidential writings, which he attributes to a warrior invocation of the god of armies from the Old Testament. Roth also mentions certain coincidences of the dates chosen by Columbus to set sail according to the Jewish calendar. For his part, both the Valencian writer Juan Atienza in his book on the Jews of Spain, as well as the historian Celso García de la Riega, and some others, describe as striking the close relations that Columbus had with prominent Jewish figures of the time, having provided him with support, financing (in the form of loans to the royal house) and facilities for cartographic study by characters such as Abraham Zacuto.

The Sephardic thesis is defended by several essayists, most accepting the admiral's Genoese origin, as is the case of Pedro de Frutos in his book The enigma of Columbus. But according to the According to Salvador de Madariaga, Columbus would be Genoese, but his ancestors would be Catalan Jews who fled persecution at the end of the xiv century. Columbus would be a a converted Jew, a reason that would explain, according to Madariaga, his determination to hide his origins. For his part, Nito Verdera maintains the theory that Columbus was crypto-Jewish and born in Ibiza. Other essayists adhere to the Galician hypothesis, such as Enrique María de Arribas y Turull.

Catalan hypothesis

One of them is the Catalan hypothesis; Luis Ulloa, a Peruvian historian who lived in Barcelona for several years, affirmed that Columbus was originally from Catalonia and from a seafaring tradition, basing himself, among other reasons, on the fact that in his writings, all in Spanish, there are linguistic twists typical of Catalan. For Ulloa, Christopher Columbus was a Catalan nobleman who would actually be called Joan Colom, a navigator who was an enemy of King John II of Aragon, against whom he fought in the service of Renato de Anjou, aspirant to the throne and who also it would be the supposed John Scolvus who would have arrived in North America in the year 1476, who would later offer the discovery project to King Ferdinand the Catholic for the benefit of the Crown of Aragon. This theory has been followed, expanded or modified by various authors, mostly Catalan historians and researchers, although there are also researchers from other countries such as the American Charles Merrill who have supported this thesis. On the contrary, this hypothesis s has been answered indicating that its supporters dedicate a large part of their efforts to refute or deny numerous historical documents that show the Genoese origin of the navigator, while they have not provided any document that demonstrates the supposed Catalan origin.

Different currents have emerged from the Catalan hypothesis, such as the Balearic theses. One of them, the Mallorcan, identifies Columbus with a natural son of the Prince of Viana born in Felanich, Mallorca. However, other experts such as the researcher, journalist and merchant pilot, Nito Verdera, have rejected this thesis.

Galician hypothesis

Another hypothesis indicates that Columbus was of Galician origin. Celso García de la Riega and later Enrique María de Arribas y Turull supported this theory, mainly based on documents from the Columbian era that recorded the existence of families that had that surname. However, these were later discredited by the paleographer Eladio Oviedo Arce, concluding that these documents were either false or had been manipulated on dates after their creation. However, in 2013 a new study considered the documents authentic, limiting itself to verifying the past presence of inhabitants with the surname Colón in the current province of Pontevedra, without ruling on the supposed Galician origin of the Admiral. In the words of María del Carmen Hidalgo Brinquis, who presented the results of the verification, this finding neither denies nor confirms the Galician origin of the navigator, since it only shows "that in Pontevedra there was a Columbus clan, but we do not know if it was the discoverer's clan." of America". A variant of the Galician theory identifies Columbus with the nobleman from Pontevedra Pedro Álvarez de Sotomayor; this hypothesis being rejected by most historians, who expose, among many documents, the testament of his son Álvaro written in 1491, where he cites "the bones of my parents (...) bring them and bury them inside the chapel that the S. Bishop D. Juan built in the Cathedral Church of Tuy", which indicates that Pedro de Sotomayor He was dead before Columbus reached the Americas.

Portuguese hypothesis

There is also the theory of Portuguese origin, which is based on the interpretation of the anagram of Columbus's signature or on the existence of supposed Portuguese words in his writings. The expert philologist Ramón Menéndez Pidal confirmed that they were Portuguese against those who maintained that they were Galician or Catalan, although the historian Antonio Romeu de Armas qualified that this was not due to his being born in Portugal but to a naturalization due to the years that he remained in that country.

The theory of Portuguese origin arose in the twenties and thirties of the xx century. Its first defender was Patrocínio Ribeiro, who pointed out that some place names used by Columbus to name his discoveries are also found in Portugal. Former minister Manuel Pestana Júnior published almost simultaneously his theory that Columbus would have been a secret agent of King John II of Portugal. Later authors would give Columbus a Portuguese aristocratic origin.

Other hypotheses

There are also other theories within Spain that attribute an Andalusian origin to it, specifically from Seville, Castilian from Guadalajara, Extremadura from Plasencia or Basque.

Other countries also dispute being the birthplace of the admiral, being of possible Greek, English, Corsican, Sardinian, Norwegian, Scottish, or Croatian origin.

Language of Columbus

About the mother tongue of Christopher Columbus there is also controversy, since, according to researchers, it is an important support for one or another theory about his hometown. To try to fix the real origins of it, various reasons have been given in every way.

Most of his writings are in Spanish, but with evident linguistic shifts from other languages of the Iberian Peninsula which, following Menéndez Pidal, many agree in pointing out as lusisms. There are various researchers and linguists, both Galicia and Catalonia or the Balearic Islands, which support the hypothesis that they are Galician or Catalan.

There do not seem to be any writings in Italian made by Columbus, except for some marginal notes, apparently with poor writing. He did not write in Italian even when he addressed his children or his brothers; not even to the Bank of San Giorgio in Genoa. When the Florentine Francisco de Bardi, his brother-in-law, sent him a personal letter in 1505, he preferred to write it in poor Spanish than in Italian. Nor did he seem to master Latin, which he wrote with influence Hispanic and not Italian.

Historians such as Consuelo Varela or Arranz Márquez believe that he is a typical man of the sea who expresses himself in various languages without mastering any of them, or that perhaps he spoke the lingua franca or rebellious jargon.

Early Years

According to the Genoese origin, overwhelmingly supported by most historians, Christopher Columbus would be the hispanicization of the Italian Cristoforo Colombo. Cristoforo can be translated as Christopher, the which carries Christ, and Colombo in Italian means dove. One of Columbus' signatures reads "Xpo Ferens", which, according to some researchers, means "bearer of Christ".

According to this, his literary education was scant and he was introduced to sailing at an early age. Between 1474 and 1475 he would have traveled to the island of Chios (Chio or Chío), a Genoese possession in the Aegean Sea, as a sailor and probably also as a trader. On the other hand, his son, Hernando Colón, assured that his father learned letters and studied in Pavía, which allowed him to understand cosmographers.

It is not clear how Columbus got to Portugal. According to the biography written by his son Hernando, it was by accident, as a result of a shipwreck in a naval combat near Cape San Vicente on an undetermined date. Columbus would have been part of the crew of a corsair named "Colón el Mozo", who attacked some Venetian ships. Columbus's ship sank, he swam to safety and reached the coast of the Algarve. From there he left for Lisbon, seeking the help of his brother Bartolomé and other acquaintances. However, it has since been proven that Hernando Colón invented this story by mixing sources about two different battles, one from 1476 (during the War of the Castilian Succession) and another from 1485.

Until 1485 he lived in Portugal as an agent of the Centurione de Madeira house and made numerous trips to various destinations, including Genoa, England and Ireland. Possibly on this trip, in the year 1477, he reached Iceland and heard rumors of the existence of other lands to the west. He had been to the Canary Islands, which implies that he would also know the "Volta da Mina", a route followed by Portuguese sailors when they returned to their country from the Gulf of Guinea and with it the trade winds of the Atlantic Ocean.

Between 1479 and 1480 Christopher Columbus married Felipa Moniz, daughter of the colonizer of the Madeira Islands, Bartolomeu Perestrelo, probably in Lisbon. Once married, he lived in Porto Santo and Madeira, which suggests that he also traveled to the Azores. His wife Felipa, from the Portuguese upper class, opened the doors for him to prepare his project. In 1480 the couple had an only son, Diego Colón. Many years later, Columbus would write that on the beaches of Porto Santo he saw objects dragged from the East, including a corpse with Asian features. This is, however, unlikely because the prevailing currents in that area are north-south, not west-east.

The project

It is difficult to estimate when Christopher Columbus' project to reach Cipango —modern Japan— and the lands of the Great Khan by sailing westward was born, but it can be dated after his marriage and before 1481.

He probably had knowledge of the reports by the Florentine mathematician and physician Paolo dal Pozzo Toscanelli on the possibility of reaching the Indies from the west, written at the request of King Alfonso V of Portugal, who was interested in the matter.

In any case, Columbus had access to a letter from Toscanelli that was accompanied by a map outlining the route to follow to East Asia, including all the islands that were supposed to be on the route. This map and Toscanelli's news stories were based mainly on Marco Polo's travels. The latter pointed out that the distance between the western end of Europe and Asia was not excessive, estimating the space between Lisbon and Quinsay at around 6,500 nautical leagues, and only 2,500 miles from the legendary Antillia to Cipango, which made navigation easier. Two letters addressed by Toscanelli to Columbus are known, collected by Father Bartolomé de las Casas in his Historia de las Indias, however, there is also controversy about their authenticity.

The books that are preserved from the library of Columbus shed light on what influenced his ideas, due to his habit of underlining the books and it follows that the most underlined would be the most read. Among those with the most annotations are the Tractatus de Imago Mundi by Pierre d'Ailly, the Historia Rerum ubique Gestarum by Aeneas Silvio Piccolomini and especially The Voyages of Marco Polo, who gave him the idea of what the Orient he dreamed of finding was like.

Columbus was based on the fact that the Earth had a circumference of 29,000 km, according to the "measurement" of Posidonius and the measure of the terrestrial degree of Ailly, without considering that he was speaking of Arabian miles and not Italian, which are more short, so that he encrypted that circumference in less than three quarters of the real one, which on the other hand was the one scientifically accepted since the time of Eratosthenes. As a result of the above, according to Columbus, between the Canary Islands and Cipango there should be about 2,400 nautical miles, when, in reality, there are 10,700.

The search for patronage

Portuguese

Between 1483 and 1485 Christopher Columbus first offered his project to King John II of Portugal. He consulted with three experts —Bishop Diego Ortiz and the Jews Maese Rodrigo and Maese Vizinho— who gave a negative opinion, after which the monarch rejected Columbus's offer. Around those same years there were other explorers who were authorized by the Portuguese king to sail to the Western Atlantic, with much more modest requests for money or privileges than Columbus seems to have made., and in 1486 Ferdinand van Olmen obtained permission to sail west from the Azores to explore and conquer the "island of the Seven Cities". According to Hernando Colón's Historia del Almirante , Juan II secretly sent a caravel following the course Columbus had indicated, but he returned without having managed to reach any new land.

The failure of Christopher Columbus before John II, perhaps added to the campaign launched by the Portuguese king against the House of Braganza, led Columbus to emigrate from Portugal to the neighboring kingdoms of Castile. He left behind his son Diego and his wife Felipa, who, contrary to what some historians have claimed, was still alive.

Castile

Although the first chroniclers and some testimonies of the Colombian lawsuits reflect that Christopher Columbus arrived in Castile, entering the Port of Palos towards the end of 1484 or the beginning of 1485, there are some authors who do not admit these events as true, although it is the most frequently supported version, although there are other theories. According to this version, in the neighboring monastery of La Rábida, he first became friends with Fray Antonio de Marchena and years later with fray Juan Pérez, to whom he entrusted his plans.

The friars supported him and recommended Fray Hernando de Talavera, confessor to Queen Isabel I of Castile. In the neighboring town of Moguer he also found the support of the abbess of the convent of Santa Clara, Inés Enríquez, aunt of the king of Castile and Aragon, Ferdinand the Catholic. Columbus went to the courts, established at that time in Córdoba, and established relationships with important personalities of the royal environment. It is unknown how long he was in La Rábida. Columbus arrived in Seville in mid-1485 and stayed several times at the Monastery from La Cartuja.

Although the Royal Council rejected his project, he managed to be received in January 1486, thanks to the support of Hernando de Talavera, by Queen Isabella, to whom he explained his plans. The sovereign was interested in the idea, but wanted to that, previously, a council of learned men, chaired by Talavera, give an opinion on the feasibility of the project, while assigning a subsidy from the crown to Columbus, poor in resources.

The Council met first in Salamanca and then in Córdoba and several years later ruled that it was impossible for what Columbus said to be true. On the other hand, Talavera feared that the voyage proposed by Columbus would violate the treaty of Alcáçovas signed with Portugal and endorsed by papal bull. It also seems that the economic and political demands set forth by Columbus were very high, as was seen later in the Capitulations of Santa Fe.

The queen then called Columbus, telling him that she was not totally ruling out his plan. While the navigator waited, he dedicated himself to selling maps and books to support himself financially.

At that time, he met Beatriz Enríquez de Arana, from Córdoba, who lived with a cousin and worked as a weaver. They never married, although at her death Columbus bequeathed her fortune to him and made her first son, Diego, treat her as her true mother. They had a son, Hernando Colón (called Fernando by some sources), who traveled with his father to America on his fourth voyage and years later wrote the Historia del Almirante Don Cristóbal Colón, a biography of his father. perhaps overly complimentary.

Columbus went back to Portugal, with the consent of the sovereigns and the king of Portugal, to negotiate on issues that are unknown. There he picked up his son Diego, whose mother had died while Columbus was in Castile. attending the return of Bartolomeu Dias from the trip in which he had discovered the Cape of Good Hope, the southern tip of Africa, after which the sea route to India through the Indian Ocean was opened to the Portuguese. Columbus, on his return to Andalusia, went to propose his project to the Duke of Medina Sidonia, who rejected it, and later to Luis de la Cerda, Duke of Medinaceli, who was interested and welcomed Columbus for two years in his palace in El Puerto de Santa María. However, when consulted, the queen sent for Columbus and promised to deal with his plan as soon as the conquest of Granada was completed.

In December 1491, Columbus arrived at the royal camp of Santa Fe de Granada. His project was submitted to a new board, convened by the queen, but it was again rejected. An important part of the opposition was due to the excessive demands of Columbus. At that time, Luis de Santángel and Diego de Deza intervened, who won for his cause to King Ferdinand, gaining his support.

The coffers of the monarchs, due to the different war campaigns and especially the one carried out during the war in Granada —which successfully culminated in the Reconquest with its capture by the Christians—, were not going through their best moments. That is why Luis de Santángel, a notary public, offered to lend the money that he was supposed to contribute to the crown, 1,140,000 maravedís. The return of this amount to Luis de Santángel is recorded in the Simancas Archive.

The Capitulations of Santa Fe

The negotiations between Christopher Columbus and the Crown were carried out through the secretary of the Crown of Aragon, Juan de Coloma, and fray Juan Pérez, representing Columbus. The result of the negotiations was the Capitulations of Santa Fe, April 17, 1492.

The legal nature of this document (binding contract or revocable grant) is still controversial today. In it Columbus obtained, "in satisfaction of what he has discovered in the Ocean Seas and the voyage he is now (...) has to do for them in service» of the Crown, the following prebends:

- The title of Admiral in all lands that he discovered or won in the Ocean Sea, with an inherited character and with the same rank as the Admiral of Castile.

- The title of virrey, also hereditary and general governor in all islands or firm lands that he discovered or won in such seas, receiving the right to propose land for the government of each of them.

- The tithe, or ten percent of the net product of the goods purchased, won, found or stumbled within the limits of the Admiralty, leaving a fifth for the crown.

- The commercial jurisdiction of disputes arising from trade in the area of its admiralty, as appropriate.

- The right to contribute to an eighth of the expedition and to participate in the same share.

The content of the Capitulations was developed in a letter of mercy dated April 30, 1492, in which the granting of the title of admiral to Columbus was conditioned to the fact that he actually discovered and won new lands and it was not given to Columbus the treatment of don.

In addition, various certificates were dispatched for the organization of the trip. According to one of them, Columbus would be Major Captain of the Navy, made up of three ships. Another certificate was a Royal Provision addressed to certain residents of the town de Palos and said that they had to provide two equipped and manned caravels as payment of a sanction imposed on said neighbors. A third royal provision granted to Columbus by the Catholic Monarchs, forced the towns of the Andalusian coasts, of a later commission directed to the town of Moguer, to cede two ships to the discovering company. Christopher Columbus executed this Royal provision in the Puerto de la Ribera of this town, seizing two ships in the presence of the notary Alonso Pardo, vessels that more later they were discarded.

Columbus in Palos de la Frontera, intervention by Martín Alonso Pinzón

When Christopher Columbus arrived in the town of Palos de la Frontera, he found himself opposed by the neighbors, who distrusted the stranger. A Royal Provision addressed to Diego Rodríguez Prieto and other residents of the town, sanctioning them to serve the crown with two caravels for two months, was read at the door of the Church of San Jorge, where the public square was located. There were also problems in the recruitment of sailors, for this reason Columbus resorted to one of the provisions issued by the monarchs in which he was granted permission to recruit sailors from among those imprisoned, although in the end this was not necessary. Finally, the The religious of La Rábida Monastery, especially Fray Juan Pérez and Fray Antonio de Marchena, managed to solve the problem of recruiting sailors, by putting Columbus in contact with Martín Alonso Pinzón, a prominent local navigator, who supported the possibility of the trip, against what people thought of the project. Pero Vázquez de la Frontera, an old sailor from the town highly respected for his experience and a friend of Martín Alonso, also had an important influence so that the eldest of the Pinzón brothers decided to support the project. company.

According to Bartolomé de las Casas, Martín Alonso contributed half a million maravedis from his personal finances, a third of the company's cash expenses. He also scrapped the ships that Columbus had seized and also fired the men that he had enrolled, he chose for the company two other caravels, the Pinta and the Niña, since he knew they were very sailboats and "suitable for the trade of navigation" because he had them leased, he made his brothers participate and, in addition, he went through Palos, Moguer and Huelva, convincing his relatives and friends to enlist, thereby obtaining the necessary crew. Prominent families of sailors from the area joined the company, such as the Niño de Moguer brothers, the Quintero de Palos and other prestigious sailors who were decisive for the final recruitment of the crew.

Columbus in Moguer

In Moguer, Christopher Columbus visited the Monastery of Santa Clara, whose abbess, Inés Enríquez, aunt of King Ferdinand the Catholic, supported Columbus's project before the Court. She also found support in the clergyman Martín Sánchez and the landowner Juan Rodríguez Cabezudo to whom she entrusted custody of his son Diego, when he left on the discovery trip.

The Niño brothers had an outstanding participation in the preparations and development of the discovery trip. Once the initial reluctance to Columbus's project had been overcome, they joined the company and encouraged the Moguereña sailors, and the rest of the sailors who usually sailed with them, to enlist in the expedition. Likewise, one of the caravels —La Niña— was owned by this family. Pedro Alonso Niño was a pilot, possibly, of the Santa María, Francisco Niño participated as a sailor in La Niña and Juan Niño as master also in La Niña, in addition, part of the crew was from the town.

The four voyages of Columbus to the Indies

Christopher Columbus made a total of four voyages to what is now known as America:

- On the first trip he sailed from the port of Palos on August 3, 1492 and, passing through the Canary Islands, where he was from August 9th to September 6th, he arrived in the Indias when he discovered the Bahamas Islands on October 12th and later also the Spanish islands — now Santo Domingo — and Cuba. He returned from La Española on January 4, arriving in Lisbon on March 4 and Palos on March 15, 1493.

- On the second trip he left Cadiz on September 25, 1493, leaving Iron on October 13 and arriving at Guadalupe Island on November 4, discovering and exploring Puerto Rico and Jamaica. He returned to Cadiz on June 11, 1496.

- On the third trip he sailed on May 30, 1498, from Sanlúcar de Barrameda, on a scale in Cape Verde, from which he sailed on July 4th, and arrived on July 31st to Trinidad Island. It exploded the coast of Venezuela. On August 27, 1499, Francisco de Bobadilla arrived, who, with the powers of the kings, imprisoned the three Columbus brothers on September 15 and sent them chained to the peninsula in mid-October, arriving in Cadiz on November 25, 1500.

- On the fourth trip, he left Seville on April 3, 1502 and arrived at La Española on June 29. On July 17 he landed in the current Honduras and returned on September 11 from Santo Domingo, arriving on November 7 to Sanlúcar de Barrameda.

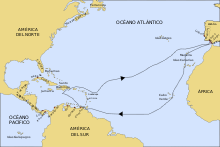

First voyage (August 3, 1492-March 15, 1493)

After all the preparations were completed, the expedition of Christopher Columbus left the port of Palos de la Frontera (Huelva) on August 3, 1492, with the caravels Pinta and Niña, and with the ship Santa María and with a crew of about ninety men. The Santa María, originally called La Gallega, was owned by Juan de la Cosa and was where Columbus embarked. The Niña, owned by the Niño family, and the Pinta were chosen by Martín Alonso Pinzón. Although in various paintings and other artistic works the presence of a priest or religious has been reflected, in this first expedition no clergyman traveled among the crew.

He was in the Canary Islands until September 6, specifically in La Gomera; according to the Historia del Almirante visiting Beatriz de Bobadilla y Ulloa, governor of the island, and in Gran Canaria, fixing the rudder of La Pinta and replacing its original triangular sails with some square, which made her the fastest caravel in the flotilla.

Heading towards the uncertain west, the expedition was not easy for anyone and during it there were several attempts at mutiny. Between 13 and 17 September they observed compass needles deviating from North Star to the west at night and to the east in the morning. This effect has been wrongly attributed to magnetic declination by some historians, but in reality it is due to the rotation of the Polaris around the north celestial pole. On September 22 Columbus sent his navigation chart to Pinzón. On the night of October 6 to 7 there was an attempted mutiny on the Santa María that it was put down with the help of the Pinzón family. However, between October 9 and October 10, the discontent spread to the rest of the expedition, and the captains determined that they would return within three days of not seeing land. On October 12, when the crew was already restless for the long voyage without getting anywhere, the cabin boy Rodrigo de Triana gave the famous cry of "land in sight!". There is also controversy about this episode among historians, since the kings had offered 10,000 maravedís to the first to sight land, however, this award was received by Columbus who, according to his logbook, would have seen "fire" a few hours before Rodrigo de Triana. They arrived at an island called Guanahani, which he renamed "San Salvador", in the Bahamas archipelago. Columbus believed he had fulfilled his long-awaited goal of reaching the Spice Indies by sailing west through the ocean. He was not aware that he had arrived on a different continent.

After October 12, Columbus traveled south to other islands of the Bahamas until he reached the island of Cuba, and later to Hispaniola (now the Dominican Republic). On its shores, on December 25, 1492, the flagship ship, the Santa María, sank. The remains of it were used to build the Fort of La Navidad, the first Spanish settlement in America.

The two caravels, under the command of the admiral, undertook the return trip to Spain. The ships were separated, la Pinta arriving first at Bayonne, around February 18, 1493. La Niña suffered a strong storm that almost caused her to shipwreck. In such a difficult situation, Christopher Columbus decided to cast lots, the promise of a pilgrimage to various temples. Columbus's ship made a stopover in the Portuguese islands of the Azores and from there arrived in Lisbon on March 4, forced by another storm. On 9 March Columbus was brought before King John II of Portugal, whom he tried to convince that the expedition was not interfering with his Atlantic possessions. Some courtiers proposed that Columbus be executed for violating the Treaty of Alcáçovas, but the king finally released him. After this Columbus set sail for Andalusia.

Finally, on March 15, the Niña arrived at the port of Palos, a few hours after the Pinta. Christopher Columbus spent a vigil night in the church of Santa Clara, fulfilling the promise or Columbian Vow made on the high seas. He also fulfilled in Huelva with the promise to light a candle in the Sanctuary of Cinta. A few days later he died Martín Alonso Pinzón, Columbus's main partner on this voyage, who was probably buried in La Rábida, according to his will.

First Pinzón and then Columbus separately sent news of their arrival to the Monarchs, who were in Barcelona. In this city, a letter from Columbus announcing the Discovery addressed to Luis de Santángel appeared in print, probably at the beginning of April. dated February 15, when they were still at sea. A very similar letter, addressed to the treasurer Gabriel (or Rafael) Sánchez and translated into Latin by Leandro de Cozco, was printed a few weeks later in Rome. This work spread rapidly throughout Europe and was translated into Italian and German..

In April 1493, Columbus was received by the Catholic Monarchs in the monastery of San Jerónimo de la Murtra, in Badalona, near Barcelona (other versions indicate that this meeting took place in the Saló del Tinell, in Barcelona), where he explained his arrival from the west in what he believed to be India.

Several years later, Europeans would begin to realize that the lands to which Columbus had arrived were not connected by land with Asia, but rather formed a different continent, which from 1507 would begin to be called America.

On May 20, the kings Ferdinand and Isabella, among the prizes and dignities granted to Columbus, granted him this extension of his original coat of arms:

The golden castle in the green field, in the picture of the shield of your weapons on the top of the right hand; and in the other high table on the left hand a purple Lion in white field ramping of green, and in the other picture below the right hand a golden islands in waves of sea, and in the other picture below the left hand the weapons you used to have. Which weapons will be known to you, and your landlords and descendants forever and ever..

The coat of arms granted by the kings was soon modified by the Columbus, although these alterations were made motu proprio, thus in 1502 in the publication of the Book of Privileges a new shield. This presents the following differences with the official coat of arms: the arms of the first and second quarters were modified to represent those of the Kingdom of Castilla and those of the Kingdom of León, the islands of the third quarter were modified accompanying them with a pointed "mainland", In order to add the new continental lands already discovered, and the fourth quarter they placed five anchors to indicate their dignity as Admiral, but not upright, but lying to the right; the primitive weapons, the ones you "used to have" by royal decree, were moved to a lower "entado".

Second Voyage (September 25, 1493-June 11, 1496)

The second voyage of Christopher Columbus left Cádiz and landed on the island of Puerto Rico on November 19.

The objective of this trip was to explore, colonize and preach the Catholic faith in the territories that had been discovered on the first trip, all under the protection of the Alexandrian bulls that protected the discovered territories from Portuguese claims.

Of the 17 ships that participated in this second voyage (three carracks, two large ships and twelve caravels), only a few are known by name, among which is la Niña, a participant of the first voyage, and the Marigalante or Santa María, namesake of the ill-fated on the first voyage, the caravel Cardera and the caravel San Juan, piloted by Bartolomé Pérez from Rota, who on his first trip was in la Niña.

On his second trip to the island of Hispaniola, he observed the lunar eclipse from September 14 to 15, 1494 and, comparing its beginning and end times with those recorded in the observations of Cádiz and Sao Vicente in Portugal, definitively deduced the sphericity of the Earth already described by Claudius Ptolemy.

In 1493 he discovered the island of Guadalupe, located about 480 km (300 miles) southeast of Puerto Rico and known to the Carib Indians as Karukera ("island of beautiful waters").

After founding the city of La Isabela, on January 6, 1494, he ordered the return to Spain of 12 ships of his fleet, keeping only the caravels Niña —now called Santa Clara (her original name)—, San Juan, Cardera and some others. In June 1496 Columbus returned from his second voyage aboard the Niña, accompanied only by the India, the first ship built in the New Lands.

Third Voyage (May 30, 1498-November 25, 1500)

On his third voyage, Christopher Columbus set sail from Sanlúcar de Barrameda captaining six ships and taking with him Bartolomé de Las Casas, who would later provide part of the transcriptions of the Diaries of Columbus.

The first stopover was made on the Portuguese island of Porto Santo, where his wife came from. From there he left for Madeira and arrived on July 31 at Trinidad Island.

The next day he arrived for the first time on continental land in present-day Venezuela. From August 4 to 12 he explored the Gulf of Paria, which separates Trinidad from Venezuela. In his reconnaissance of the area he reached the mouth of the Orinoco River, he sailed around the islands of Chacachacare and Margarita and renamed Tobago ("Bella Forma") and Granada ("Concepción"). They landed in the Macuro area, in Venezuela, in August 1498, this region being already part of the American continental mass.

Initially, he described the lands as belonging to a continent unknown to Europeans, but later backtracked and said they belonged to Asia.

On August 19, he returned to Hispaniola to find that most of the Spaniards settled there were discontented, feeling deceived by Columbus about the riches they would find. Columbus repeatedly tried to agree with the rebels, the Taínos and the Caribs. Some of the returning Spaniards accused Columbus in court of bad government. The kings sent the royal administrator Francisco de Bobadilla to Hispaniola in 1500, who on his arrival (23 August) arrested Columbus and his brothers and shipped them to Spain. Columbus refused to have his shackles removed throughout his voyage to Spain, during which he wrote a long letter to the Catholic Monarchs.When he arrived in Spain he regained his freedom, but he had lost his prestige and his powers.

Minor or Andalusian trips

Despite the intention of Admiral Columbus to reserve the monopoly of the conquest and colonization of the lands to which he had arrived, the Crown did not have those ideas. In this way, he capitulated to the conditions of new voyages, whose objective was to discover lands unknown to the Europeans and in no way colonize them.

These trips took place from 1499 and include the following:

- Alonso de Ojeda and Juan de la Cosa in 1499, in which Américo Vespuccio participated, whose name would give to the dessert the name to the continent. They arrived to the present Venezuela and gathered news about wealth. These news were investigated by other sailors, who eventually found pearl deposits.

- In the same year, 1499, Vicente Yáñez Pinzón became the first European to reach the Amazon River and, according to various historians, it must be considered the true discoverer of Brazil. He returned to the peninsula on September 30, 1500 with a shipment of a highly quoted wood called stick brasil. In a new capitulation, signed with King Fernando, on September 5, 1501, he appointed him captain and governor of Santa María de Consolación until the mouth of the Amazon River, but he did not return to the area. In the year 1508 he returned to the Caribbean with the mission of looking for a step to the Pacific Ocean, explored the entire coast of Central America and the Yucatan peninsula, establishing the first contact with the Mayan civilization.

These trips, although limited in their objectives, provided great information to the Crown and the Casa de la Contratación.

Fourth Voyage (April 3, 1502-November 7, 1504)

Between 1500 and 1502 Columbus, feeling harassed by his enemies, launched an imaging operation. In 1501, his friend Pedro Mártir wrote what can be considered the "official biography" of the Admiral. The following year, Columbus bequeathed 10% of his income to the city of Genoa to curry favor with him while Genoese merchants provided the necessary financing for a new voyage of exploration to the Indies.

The fourth and last voyage of Christopher Columbus departed from Seville on April 3, 1502, he headed for Puebla Vieja and later Columbus kept busy in Seville for ammunition and crew matters while the ships waited in Cádiz, from where they sailed on May 11. On May 25 they stopped at Gran Canaria and, after a 21-day journey across the Atlantic, they reached the Caribbean, landing in a bay in Hispaniola. Columbus explored the coasts of present-day Honduras, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, and Panama. From this gulf he attempted to return to Hispaniola, but a storm forced him to land in Jamaica, because he did not obtain permission from the Governor of Hispaniola. From there he turned to the Isle of Pines (Cuba) to end up on the mainland.

In October 1502 he arrived at Chirqui Bay (Panama), believing he saw the passage to the Indies, the mythical Western Passage. The indigenous people told him about a step to reach the Great Ocean (Pacific Ocean). Columbus, as a sailor, refused to enter the jungle. Had he done so, he would have been the first European to do so.

On December 5, 1502, he gave up the search for the Western Pass for a purely economic exploitation, heading to Veragua (Panama) where he found gold in the torrents that came down from the mountains, advised by his brother Bartolomé. In April 1503, after four months in Veragua, they founded the settlement of Belén, with 80 people, under the command of his brother Bartolomé and his notary Diego Méndez. On April 6, 1503, the Guarani attacked Bethlehem in a ratio of 10 to 1 in favor of the indigenous people. Despite the Spanish technological superiority (arquebuses against arrows and macanas), they must abandon the settlement and go to sea, to the north.

With the wood of the ships' hulls rotting and water constantly coming in, he suffered the fourth storm of the voyage, running his ships aground in Jamaica. With the remains of the shipwreck, they made a camp on the beach. Given the certainty that no one was going to rescue them (no ship had arrived in Jamaica since 1494), Columbus trusted his notary, Diego Méndez, for a suicide mission: go to Hispaniola in a canoe and seek help from its Governor, Nicolás de Ovando..

After 5 days of crossing between Jamaica and Hispaniola, they arrived at the island, where its Governor, fighting against the natives, refused to help Columbus and retained Diego Méndez for months. Meanwhile, in Jamaica, there was a mutiny led by the Porras brothers to undermine the command of an already ailing and arthritic Columbus, who failed at first by not being able to leave Jamaica.

On February 29, 1504, there was a lunar eclipse predicted by Columbus that frightened the frightened native Jamaicans into making offerings to him. However, he only bought some time, because through a sent emissary, Nicolás de Ovando sent him his refusal to send a ransom.

After eight months of waiting, on September 11, 1504, a sick and exhausted Columbus and his son Hernando managed to re-embark in Jamaica bound for Hispaniola, on a ship obtained by Diego Méndez. Columbus had to pay for his passage. Surprisingly, this short trip lasted 45 days, compared to the 5 that Diego Méndez invested in a canoe, due to the adverse sea conditions.

110 of the 145 members of the expedition survived, although many of them, exhausted, gave up returning to Castile and stayed on Hispaniola.

In 1503, on his last voyage through the Greater Antilles, he discovered the islands now called Cayman Brac and Little Cayman (because Columbus never saw the island of Grand Cayman), which received the name Las Tortugas. He gave them that name because of the large number of turtles that were in and around them. He returned to Sanlúcar de Barrameda in 1504 without fulfilling any of his main objectives.

Relations with indigenous people

Following the customs in force at that time, the relations of Christopher Columbus and his men with other peoples and lands were governed by the possibilities of conquering them for the kingdom they represented.

Thinking that they were in the lands of the Great Khan, they tried to take defensive military positions and establish contact with a king, but they found nothing similar and gradually verified that they possessed a great weapons superiority over the natives and that they were unaware of the words "Great Khan". They attributed this lack of knowledge to a very low cultural level of the Indians and they began assuming the ease of conquest of the new territory. This was demonstrated in the communications to their monarchs.

Activity as a cartographer

Although no map signed by Columbus has survived, several indications point to the fact that he did draw some maps. Las Casas and other authors of the 16th century claim that Columbus earned his living occasionally by making nautical charts. Las Casas also relates that, sailing along Cuba in 1492, Columbus was drawing a map of the coast. In the correspondence between Columbus and the kings, maps of the new lands that the sovereigns claim or that Columbus claims to have sent are mentioned several times. It is also recorded that Alonso de Ojeda had access to a map of the South American continental coasts made by Columbus (or by someone in his service) during his third voyage.

Around 1501 Columbus stated in a letter that he knew how to draw terrestrial planispheres:

our lord (...) gave me (...) engenio en el anima e manos para debusar Espera y en la çibdades ryos yslas yslas y ports todo en su propia sytio.Columbus Charter to the Kings included in the Book of Prophecies

| Maps without signature or date attributed to Cristóbal or Bartolomé Colón | |||||||||

| |||||||||

Testament

On May 19, 1506, one day before his death in Valladolid, Christopher Columbus drew up his will before Pedro de Inoxedo, notary public of the Catholic Monarchs. He left his son Diego Colón, his brother Bartolomé Colón, and Juan de Porras, treasurer of Vizcaya, as testamentaries and executors of his last wishes.

In that document Columbus, who called himself admiral, viceroy and governor of the islands and mainland of the Indies discovered and to be discovered, established the following:

I made my dear son Don Diego, for my heir to all my possessions, and my offspring, which I have of swear and inheritance, that I should do in the greater part, and not by avenging the son heir male, that my son don Fernando inherit for the same month guise, and not by the same as the son heir, that he inherits Don Bartolome my brother for the same guise. E non herede mujer, except if non faltase non se fallar hombre; and if this acaesçiese, be the muger more close to my linia.

From which it is understood that he has two sons, Diego and Fernando, and that the heir is the first-born, according to custom. He also states that Doña Beatriz is Fernando's mother, which attests that they never married.

In his will, Columbus complained about the small amount —one cuento (million) of maravedíes— that the Catholic Monarchs had invested in 1492 for the discovery enterprise, having himself to contribute capital for the voyage. However, the myth invented by his son Hernando and propagated by Bartolomé de las Casas that Columbus died poor is false. His economic situation at the end of his life was that of a millionaire, with an estimated annual income of about 8,000 pesos (about four million maravedis).

Death, burial and subsequent transfers

Christopher Columbus died in Valladolid on May 20, 1506, presumably from complications derived from gout or arthritis suffered for years. After his death, his body was treated with a process called descarnation, through which the all the meat from the bones for the best preservation of the corpse.

He was initially buried in the Convent of San Francisco in Valladolid and, later, his remains were transferred to the chapel of Santa Ana in the Monastery of La Cartuja in Seville in 1509. The Florentine merchant Simón Verde was in charge of the transfer. family friend.

In 1523, at the wish of his son Diego Colón, he arranged in his will that both his remains and those of his father were transferred and buried in the Santo Domingo Cathedral.

The procedures related to the fulfillment of the testamentary will of Diego Columbus were in charge of his widow, the Viceroyalty María Álvarez de Toledo y Rojas, who through the good offices of Queen Isabella, requested and obtained from King Carlos I of Spain the authorization for Christopher and Diego Columbus to be transferred and buried in the main chapel of the Cathedral of Santo Domingo. María, on June 2, 1537, extended the right in favor of hers, her son Luis Colón.

There are discrepancies about the exact date when María de Toledo transferred the remains, since in 1536 the viceroy asked the monks of the Carthusian monastery of Santa María de la Cuevas in Seville to deliver the remains of both admirals, other sources mention that the transfer of the remains took place before 1539 and others, that the viceroy María Álvarez de Toledo took them with her on her return to Santo Domingo on August 8, 1544.

What is indubitable is that in 1548, when María wrote her will, the remains of both characters were already in the said cathedral, since María asked that her body not be buried in the same tomb as her husband Diego, but under of him, on the floor of the chapel, next to the presbytery of the main altar.

The mortal remains of Christopher Columbus remained entombed in Santo Domingo for more than two centuries.

After the conquest of the island of Santo Domingo in 1795 by the French, they moved to Havana and, after the Cuban war of independence in 1898, their remains were transferred aboard the Conde de Venadito cruise ship to Cádiz and from there to Seville by the Giralda sign bound for the Seville Cathedral, where they rest in a sumptuous catafalque.

Discussions about his burial

Subsequently, there was a controversy about the final destination of the remains of Christopher Columbus, after appearing in 1877, in the Cathedral of Santo Domingo, a lead box containing fragments of bones and bearing an inscription that read " Illustrious and distinguished man Christopher Columbus. Those remains remained in the Santo Domingo Cathedral until 1992, the year in which they were transferred to the Columbus Lighthouse, a pharaonic monument built by the Dominican Republic to honor and preserve the remains that are also supposed to be Columbus.

Apparently, at the time of exhuming the body from the Santo Domingo Cathedral it was not very clear which was the exact tomb of Christopher Columbus, due to the poor condition of the tombs, which makes it at least likely that they were only collect part of the bones, leaving the other part in the cathedral of Santo Domingo. Studies are still lacking that are more conclusive in this regard.

To find out what the real remains were, it was proposed to take DNA samples from both skeletons: the one from Seville and the one from Santo Domingo. The studies were to end in May 2006, but in January 2005 the Dominican authorities postponed the opening of the tomb. In the preliminary study, a probable filial link was detected between the bones buried in the Seville Cathedral and those of his son Diego.

On August 1, 2006, the research team led by José Antonio Lorente, forensic doctor and director of the Genetic Identification Laboratory of the University of Granada, who studied the skeletal remains attributed to the admiral that have been in Seville Cathedral since 1898, confirmed that "they are those of Christopher Columbus." This affirmation is based on the study of the DNA compared with that of his younger brother Diego and with that of his son Hernando.

Based on the research team's studies, it was determined that Christopher Columbus was

male, between 50 and 70 years, without pathology marks, without osteoporosis and with some cavities. Mediterranean, medium-sized and medium-sized.

It is still expected that the authorities of the Dominican Republic allow the study of the remains attributed to the Admiral that are in that country, which would allow completing the story around this issue. But this study is no longer decisive for identifying the remains of the discoverer. It is estimated that there may be remains in other places, since those in the Andalusian capital do not reach 15% of the entire skeleton, so it could be that those in Santo Domingo also correspond to the discoverer of America.[citation required]

Accusation of tyranny

After his first voyage, Christopher Columbus was appointed viceroy and governor of the Indies under the Santa Fe Capitulations. This included administration of the colonies on the island of Hispaniola, whose capital was established at Santo Domingo. By the end of his third voyage, Colon was physically and mentally exhausted: his body afflicted with arthritis and his eyes with ophthalmia. In October 1499, he sent two ships to Spain, asking the Court to appoint a royal commissioner to help him govern.

By then, the accusations of Columbus's tyranny and incompetence as governor had reached the Court. Queen Isabella and King Ferdinand responded by removing Columbus from power and replacing him with Francisco de Bobadilla, a member of the Order of Calatrava.

Bobadilla, who was governor from 1500 until 1502, when he died in a storm, had also been commissioned to investigate allegations of brutality made against Columbus. When Bobadilla arrived in Santo Domingo, while Columbus was busy with his third voyage explorations, he was greeted with complaints against the three Columbus brothers: Cristóbal, Bartolomé and Diego. A recently discovered report from Bobadilla asserts that Columbus frequently used torture and mutilation to rule Hispaniola. The 48-page report, found in 2006 in the General Archive of Simancas, contains testimonies from 23 people, including Columbus enemies and supporters, about Columbus's and his brothers' treatment of colonial subjects during their seven-year rule.

According to this report, Columbus punished a man guilty of stealing corn by having his ears and nose cut off, then sold as slaves. The testimonies recorded in the report assert that Columbus congratulated his brother Bartolomé for "defending the family" when the latter ordered that a woman be forced to parade naked in public and have her tongue cut out for suggesting that Columbus was of bad birth. The document also described how Columbus controlled the discontent and revolt of the natives. First, he ordered a brutal crackdown in which the natives were killed and then their dismembered bodies paraded through the streets in an attempt to discourage any further rebellion.

"Columbus' government was distinguished by a form of tyranny," says Consuelo Varela Bueno, a Spanish historian who has studied and published documents. "Even those who admired him [Columbus] had to admit the atrocities that had occurred." Varela Bueno affirms in the prologue of his book, that "The historiography that has been preserved to us until now is solely and exclusively the one that favored him." and as a result of his investigation he concludes that «Columbus, despite his greatness, is not a nice character. He is now even less so ».

Bartolomé de las Casas wrote that when he arrived in Hispaniola in 1508 there were, counting all the Indians, more than 60,000 people living on the island, so that from 1494 to 1508 around three million Indians would have died in wars, because of slavery or work in mines, and concluded by exclaiming: «Who of those who will be born in the coming centuries will believe this? I myself who wrote it and saw and know most of it, now it seems to me that it was not possible". The death figures given by Las Casas have been considered implausible by American historians John Tate Lanning and Philip Wayne Powell, the Argentine Enrique Díaz Araujo and Spanish Elvira Roca Barea. Demographic studies such as those carried out in colonial Mexico by Sherburne F. Cook in the middle of the century XX suggested that the decline in the early years of the conquest was truly drastic, ranging from 80 to 90%, due to many different causes but all of them ultimately attributable to the arrival of the Europeans. The main and overwhelming cause was disease introduced by Europeans. Various historians have also pointed out that exaggeration and inflation of figures was the norm in accounts of the 16th century, and both detractors like contemporary supporters of Las Casas were guilty of similar exaggerations.

The government of the Columbus brothers in Hispaniola did not meet the expectations of the Catholic Monarchs. From the outset, the position of Queen Isabella I of Castile herself in defense of the equality of the Indians, her subjects from the New World, and the Spanish, her subjects from the Old World, was clear. The attacks on indigenous people and the sale of some as slaves was a disobedience to the express orders of Queen Isabella the Catholic, who had made clear her wish that the indigenous people be treated as subjects of Castile, and therefore, as human beings. free.

For this reason, Columbus was arrested after his third voyage and sent in chains before the queen by the investigator Francisco de Bobadilla. Columbus's behavior did not correspond to what Spain proposed in its laws, although the distance between Other reasons led to behaviors similar to those of Columbus with the natives, which were denounced by Fray Bartolomé de las Casas and disapproved by the New Laws. Columbus and his brothers were in prison for six weeks before King Ferdinand ordered his release. After a short time, the king and queen called Columbus and his brothers to the Alhambra palace in Granada. There, the monarchs listened to the pleas of the brothers, returned their freedom and wealth, and after much persuasion, agreed to finance Columbus's fourth voyage. However, Columbus never got back his role as governor, which at that time was assumed by Nicolás de Ovando y Cáceres, the new governor of the West Indies.

Posterity

Formation of the myth

In the 16th and 17th centuries several visions of Columbus coexisted. One of them, favored by the Hispanic Monarchy, was the providential vision that saw Columbus as the instrument chosen by God to reveal the New World to (European) Humanity and place it in the hands of the Catholic Monarchs. The greatest exponent of this vision was Antonio de Herrera, who based himself on the biography written by Hernando Colón and on the unpublished manuscripts of Bartolomé de las Casas. The first great theatrical work dedicated to the character also dates from this period, created by Lope de Vega, in which he is presented as an envoy of God. In the rival powers of Spain, on the contrary, the Columbian discovery was attributed to mere good luck (for example the British Daniel Defoe in 1725)[citation required] or the inks were loaded on the crimes perpetrated by Columbus against the natives (French Abbe Raynal, 1770).

In 1777, Scotsman William Robertson introduced a new perspective: Columbus, a man of science, a genius ahead of his time. Robertson believed in the view of history put forward by earlier Scottish writers such as Adam Smith, who claimed that all human society progresses through a series of levels of civilization, from the most primitive of hunting, to herding, then to agriculture, and then on. end to "commercial". For Robertson, Columbus had been the culmination of a series of explorations that took Europe from the agricultural to the commercial phase of history. This heroic and enlightened vision of Columbus was very well received in the newly independent United States, which merged it with the female figure of Liberty to give rise to Columbia, a personification that became one of the symbols of the new republic as well as a the name of the federal capital district in 1791.

The Spanish historian Martín Fernández de Navarrete published in 1825 the first volume of a collection of essential archival documents to understand the reality of Columbus, his voyages and the discovery of America in general. The US ambassador to Spain hired the writer Washington Irving to translate Navarrete's work into English. However, Irving preferred to compose a fictionalized story based on this information, projecting onto Columbus the ideals of the discoverer of the Romantic era, personified at that time in Alexander von Humboldt. To this end, Irving did not hesitate to add invented episodes when it suited him, for example a non-existent debate in Salamanca between the "scientist" Columbus and some religious obscurantists who defended that the Earth was flat; or in denigrating the crew members and companions of Columbus, whom he branded as "dissolute rabble". Irving's work was a huge bestseller, being translated into six other languages including Spanish, and defined the vision of Columbus that endured until at least the mid-century XX, and was reflected in film productions such as 1492, the Conquest of Paradise.

Legacy

The historic trial

As a result of the revolution that marked the discovery of America led by Christopher Columbus, his figure and his name, as well as its variants, appear in numerous places and also in the arts, culture and education. A country, states, cities, schools, streets and parks are named after him, as well as sculptures and monuments honor him, so that the figure of Columbus has become a world icon. Novels, stories have been written about his life, musical pieces and dramatic works have been composed both in theater and in cinema. There was an attempt from the Catholic hierarchy to canonize him as a "propagator of the faith".

The practically unanimous admiration of Christopher Columbus during the XIX century, reached its culmination in 1892, when the IV was commemorated Centenary of its maiden voyage, understood in the context of the Second Industrial Revolution and the rise of colonialism, as a milestone of civilization. The few critical voices avoided focusing on him, and blamed the ills of the conquest on Spanish and Portuguese (to a lesser extent French and English), presenting Columbus as an explorer and champion of scientific thought. In relation to this idea, the myth of the medieval belief in a Flat Earth was entrenched, which Columbus would have challenged with his voyage.

In the XX century, this unanimous admiration for Columbus disappeared when his actions were related to the processes events that triggered, especially the Conquest of America. For this reason, some historical researchers and popularizers questioned Columbus as a representative of Eurocentrism and cultural imperialism, others preferred to highlight that, as a man of his time, he acted according to values and a belief system that are different from those of later centuries..

Commemorations

Different countries commemorate the Columbian landing in America on October 12, 1492, an initiative that was formulated around the celebrations of the IV Centenary of the Discovery. In Spain this date has been adopted as the National Holiday of Spain (until 1987 also called Día de la Hispanidad), different Latin American countries celebrate it, or celebrated it, with the name of Día de la Raza in the context of affirmation of identity at the beginning of the 20th century. Thus, Argentina (a pioneer since 1917 and until 2010 when it changed its name), Venezuela (between 1921 and 2002), Mexico (since 1928) and Chile (since 1931) adopted it as part of their calendar of civic festivals. In the United States, October 12 is commemorated as Columbus Day.

The rise of national liberation movements from the 1960s and 1970s, the emergence of new anthropological concepts of culture and civilization, criticism of colonialism and neocolonialism, and the emergence of a historiography based on the study of social processes, rather than in events, and in the collective role, more than the individual led to questioning the idea of "discovery" and Columbus's own actions, especially as the one who began the conquest of America. Once the biased ideas of Leyenda Negra and Leyenda Rosa had been overcome, towards the V Centenary two visions of this process appeared. One of them focused on subsequent developments and preferred to consider it as an "encounter", not without conflicts, between two worlds, during which, which began with Columbus, knowledge of the world was completed and the foundations of a global civilization interconnected by trade and culture were laid. The other considered that the processes of colonial domination were still in force both from the developed world and within postcolonial societies and that contempt for indigenous peoples in America and Europe and the asymmetry in the relations between the developed world and the Third World, were the consequence of what happened since October 12, 1492; for this interpretation, therefore, "no there is nothing to celebrate" and the date should be commemorated rather than celebrated.

While the Celebration of the IV Centennial in 1892 had been an apotheosis of Columbus, the celebrations of the Quincentennial in 1992 were carried out under the title of "Encounter of Two Worlds", agreed upon by Unesco with the approval of all the governments involved, which made Columbus less prominent in addition to avoiding the controversial term of "discovery". However, the celebrations were rejected as a "new conquest" by indigenous movements, left-wing parties in some countries, and other organizations. In the United States, where "Columbus Day" it was a date dedicated to celebrating the European legacy (especially Italian) and the audacity of the Genoese, there were no big celebrations in 1992. The National Council of Churches of this country declared that it was not a day to celebrate, but to " reflection and repentance".

Starting in the XXI century, some left-wing Latin American and Spanish governments began to officially question the celebration of the 12th October. Thus, in 2002, the president of Venezuela, Hugo Chávez —in accordance with the so-called Bolivarian thought— changed the name of Day of the Race to Day of Indigenous Resistance. Likewise, the National Indian Council, representing the 36 Venezuelan indigenous ethnic groups, requested that the statues of Christopher Columbus be removed and that they be replaced by that of the cacique Guaicaipuro who resisted the Spanish invasion. That same day a group of indigenous activists demolished the statue of Columbus located in Caracas.

In 2007, a variant of the same name - Day of Indigenous, Black and Popular Resistance - was adopted by Nicaragua and in 2017, the Parliament of Navarra commemorated October 12 also as Day of Indigenous Resistance.

In Argentina, President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner by means of a decree changed, in 2010, the name of Columbus Day to Day of Respect for Cultural Diversity, on the recommendation of INADI, in line with the idea that there are no races and in order for it to become a "...day of historical reflection and intercultural dialogue". In 2013, the transfer of the Monument to Christopher Columbus (a gift from the Italian community in commemoration to the Argentine Centennial) located behind the Casa Rosada, generated some controversy.

Toponymy

As far as toponymy is concerned, the name of Columbus is widely used, mainly in America. An American country, Colombia owes its name to the Admiral, as does its highest mountain, Pico Cristóbal Colón; as well as different regions, cities and rivers such as Columbus in Ohio (United States) or the City of Colón in Panama, as well as the province of the same name. In the United States, the Columbia form was adopted above all, a fusion of the heroic ideal of Columbus with the feminine figure of Liberty, for example in Columbia (South Carolina), the District of Columbia where the federal capital Washington D.C. is located., the Columbia River or the Canadian province of British Columbia.

In Argentina there are two cities called Colón, one in the province of Buenos Aires and the other in the province of Entre Ríos. In Cuba there is also a city called Colón, in the province of Matanzas, as well as the country's main cemetery: the Necropolis of Cristóbal Colón in Havana. Puerto Colón —in Paraguay—, Ciudad Colón —in Costa Rica—, Colón —in Mexico—, San Juan de Colón —in Venezuela—, San Marcos de Colón in Honduras. Likewise, the archipelago of the Galapagos Islands, belonging to Ecuador, officially receives the name of "Archipielago de Colón".

In Spain, specifically in the province of Huelva, there is the historical-artistic route of the "Columbian Places" around the figure of Columbus, the Pinzón brothers and the events surrounding the discovery. It was declared a historical-artistic site of the province in 1967.

The Egg of Columbus

The DLE defines the Columbus egg as: "Something that appears to be very difficult but turns out to be easy when knowing its artifice." The origin of this saying is related to an anecdote published by Girolamo Benzoni in the book History of the New World (Venice, 1565). This places us in a game between Columbus and a group of nobles. In response to a question about the discovery, Columbus asked for an egg and invited the nobles to try to make the egg stand upright on its own. The nobles were unable to keep the egg upright and when it returned to their hands, Columbus slammed the egg against the table, cracking it slightly and causing the egg to stand. Although this anecdote is likely to be a legend, it has become very popular.

Theatre, film and television

In 1614 Lope de Vega wrote The New World Discovered by Christopher Columbus, the first great play dedicated to the character of Columbus, in which he is presented as an envoy from God.

In the first two decades of the xx century, three films titled Christopher Columbus were made, directed by Vincent Lorant-Heilbronn (1904), Emiliano Fontana (1910) and Gérard Bourgeois (1917). All three highlighted the supposed Christian missionary character of Columbus. The experimental play published in 1933 by Paul Claudel, a markedly Catholic French author, is inscribed in the same hagiographic vein under the title Le livre de Christophe Colomb.

The first great film dedicated to Columbus was made in 1949 by the British David MacDonald. Titled Christopher Columbus (Cristóbal Colón in the Spanish version), Fredric March's performance in the title role stood out. The following super-productions on the same subject did not arrive until the Fifth Centenary of the Discovery, in 1992, when two films were released within a few months. The first was Christopher Columbus: The Discovery, directed by John Glen and starring George Corraface. It was followed by 1492: The Conquest of Paradise, directed by Ridley Scott and starring Gérard Depardieu. Both films were described as mediocre by critics.