Chiroptera

The bats (Chiroptera, from the Greek cheir, "hand" and pteron, "ala"), commonly known as bats, are an order of placental mammals whose upper limbs developed as wings. With about 1,400 species today, they represent approximately 20% of all mammal species, making them, after rodents, the second most diverse order in this class. They are present on all continents except Antarctica.

Are the only mammals capable of flight, they have spread almost all over the world and have occupied a wide variety of different ecological niches. They play a vital ecological role as pollinators, as pest controllers of insects and small vertebrates, and also play an important role in seed dispersal; many tropical plants are completely dependent on bats. They have forelimbs transformed into wings and more than half of known species orient and hunt by means of echolocation. About 70% of species are insectivorous and most part of the rest frugivorous; some feed on small vertebrates such as frogs, rodents, birds, fish, other bats or, as in the case of vampires (subfamily Desmodontinae), blood.

Its size varies from the 29-33 mm in length and 2 g in weight of the bumblebee bat (Craseonycteris thonglongyai), to more than 1.5 m in wingspan and 1.2 kg in weight. weight of the Philippine flying fox (Acerodon jubatus).

Because of the nocturnal habits of most of their species and the age-old misunderstanding of how they could "see" in the dark, they were and often are still regarded as sinister denizens of the night, and with few exceptions (as in China, where they are a symbol of happiness and profit) in most of the world bats have caused fear among humans throughout history; Essential icons in horror movies, they appear in a multitude of myths and legends and, although only three species are actually blood-sucking, they are often associated with mythological vampires.

Etymology

The scientific name of the order, Chiroptera, comes from two Greek words, cheir (χειρ), hand, and pteron (πτερον), wing. Although few bats are completely blind, in the past the belief that they were blind predominated, as evidenced by the origin of their common name, "bat", which is a historical metathesis of "bat", formed by the Old Castilian expression mur cego 'blind mouse', which in turn derives from the union of the Latin terms mus, mouse, caecŭlus (diminutive of caecus), blind, and alatus, winged. In other languages, its name is also a compound word that alludes to its resemblance to these rodents and its ability to fly, such as ratpenat (winged rat) in Catalan, or Fledermaus (mouse that flies) in German, in Basque it is called sagu zahar (old mouse), the Chinese call it sein-shii (celestial mouse) and the Aztecs called it quimich-papalotl, from quimich, mouse, and papalotl, butterfly.

The term "vampire", which is used as a common name for blood-sucking bats, comes from the French vampire, and this from the German Vampir. This word has its origin in the mythical vampires, a term that is generally accepted to have its origin in the Slavic and Magyar languages, although its etymological origin is uncertain.

Morphology

Bats, along with birds and the now extinct pterosaurs, are the only vertebrate animals capable of flight. To achieve this, they have developed a series of characters intended to allow flight; Except for the thumb, all the fingers of the hands are particularly elongated and support a thin, flexible and elastic skin membrane, which guarantees support. This membrane, called patagium, is made up of two layers of skin that cover a central layer of innervated tissues, blood vessels, and muscle fibers.

Their fur varies from species to species, but is generally brown, grey, yellow, red, and black. Its size ranges from the 29-33 mm length and 2 g weight of the bumblebee bat (Craseonycteris thonglongyai), the smallest mammal extant today, to the more than 1.5 m in length and 1.2 kg in weight of the great Philippine flying fox (Acerodon jubatus). Other large bats include the Indian flying fox (Pteropus giganteus), Livingston's flying fox (Pteropus livingstonii) or the great flying fox ( Pteropus vampyrus), the largest bat. Despite their name, megabats are not always larger than microbats, as some species are only six centimeters in length and smaller than the largest microbats.

The orientation of its lower extremities is unique among mammals; the hip joint is rotated 90° so that the legs are projected to the side and the knees face almost to the rear. Partly due to this rotation, their gait is generally clumsy and sets them apart from other tetrapods. This design of the lower extremities supports the patagio in flight and allows them to hang upside down, a position in which they spend much of their lives, hanging from the branches of trees or from the ceilings of the caves where they live. They also have a free toe and is endowed with a nail that helps them hang and climb. When they are hanging, their weight exerts a traction on the tendons that keeps the claws in the hooking position, which allows them to remain hanging even when asleep and not expend energy even if they remain in that position for long periods of time.

Skeleton

The main skeletal adaptation of this order of mammals is a pronounced elongation of the chyridia, especially in its bones furthest from the midline. The radius is long and the ulna is reduced and is fused with it, and the humerus is also very long and with a large head, articulated with the scapula in a special way, since flight movements occur above all at shoulder level, the rest of the limb remaining rigid; the elbow only allows flexion-extension movements and the carpus performs the flexion-extension and unfolding of the fingers. The first finger is robust and external to the wing and is always provided with a nail (in the case of megachiroptera also the second finger); the rest of the metacarpals and proximal phalanges are especially elongated to support the patagium, with the distal phalanges relatively short. The hind limbs are weak and have five clawed fingers, which they use to hang without the need for muscle contraction.

The sternum forms a keel where its powerful pectoral muscles attach, and the broad, vigorous clavicle is often fused to the sternum and scapula. The ribs are wide, have little mobility, and can fuse with each other and with the vertebrae, making their breathing predominantly diaphragmatic. The pelvis has evolved to accommodate flight; it is displaced so that the acetabulum is located dorsally and the paw is held out and up, and generally lacks a pubic symphysis; in microbats, the ilium and sacrum are fused to the level of the acetabulum, thus lacking mobility at the iliosacral junction, and in flying foxes the two bones are completely fused. The sternebrae are stout and fused, and the neural spines, the vertebral column itself, and especially the lumbar region are short. The column is composed of seven cervical vertebrae, eleven thoracic vertebrae, and up to ten caudal vertebrae; to support its powerful flight muscles, the thoracic vertebrae are tightly attached to each other to form a rigid column.

Head

Its head differs considerably from species to species. The head of many bats resembles that of other animals such as mice, but they have differential structures in bats. Many have nasal blades or other structures on the face, which serve to emit or enhance the ultrasound. The ears, which in many species are large, are often furrowed or wrinkled, in addition to the tragus, a lobe of skin that enhances their ability to echolocate.

Microbats have dichromatic black-and-white vision, while Megabats see in color. Although the eyes of most Microbats are small and underdeveloped, with low visual acuity, it cannot be said that be blind They use sight as an aid in navigation, especially over long distances, which are not reached by echolocation. According to recent research, some species also perceive ultraviolet light reflected from some flowers, which would help them find nectar. Some have a sense of magnetoreception, which allows them to orient themselves using the Earth's magnetic field, similar to birds. migratory birds and other animals, and helps them orient themselves during their nocturnal flights. Lacking echolocation, the eyes of megabats are more developed than those of microbats, and they use smell and sight to orient themselves and locate their food; its ability to gather light is enhanced by numerous projections from the retinal rods.

They generally have between 32 and 38 teeth, of which the canines are specially developed. The evolution of different feeding modes has developed multiple dental configurations, and in this order of mammals some 50 different dental formulas are known; the common vampire (Desmodus rotundus), with twenty teeth, is one of the bat species with the least number. The teeth of microbats are similar to those of insectivorous animals; they are very sharp in order to penetrate the tough exoskeleton of insects or the skin of fruit. Those of the megachiroptera are adapted to bite the hard skin of some fruits.

The species Anoura fistulata has the longest tongue in relation to body measurement of all mammals. With its long and narrow tongue it can reach the bottom of many flowers with an elongated conical receptacle, and helps it to pollinate and feed. When you retract your tongue, it curls up inside your ribcage.

Wings

Chiroptera are an example of the great variety of development possibilities that tetrapod legs can have. Except for the thumb, all the phalanges of the fingers of its forelegs are specially elongated to support an extensive and thin membrane of skin, flexible and elastic, which is called patagio and which allows it to sustain itself in the air. The patagium is formed by a central layer of tissues riddled with nerves, blood vessels and muscle fibers, covered on both sides with layers of skin. The patagium is divided into propagium (the part that goes from the neck to the first finger), dactylopatagium (between the fingers), plagiopatagium (between the last finger and the hind legs) and uropatagium (caudal or interfemoral membrane, which joins both hind limbs together, including the tail in whole or in part). Depending on the species and their style of flight, they can have a very long uropatagium, be smaller or even lack it; likewise some such as Anoura spp. and Sturnira spp. they lack obvious uropatagium and the genera Desmodus, Diphylla and Diaemus lack a tail but have uropatagium, albeit very narrow.

The bones of the fingers are much more flexible than those of other mammals. One reason is that cartilage lacks calcium and other minerals at its end, which allows it to twist without breaking. The section of the finger bones is flattened, instead of circular as for example in humans, which makes them even more flexible. The skin of the wing membranes is very elastic and can be stretched much more than is usual in mammals.

Since they have much thinner wings than those of birds, being more similar by convergent evolution to that of pterosaurs, they can maneuver more quickly and precisely, although they are also more delicate and tear easily; however, the membrane tissue replaces itself in a short time, so these small tears can heal quickly. The wing surfaces are endowed with touch-sensitive receptors in the form of small bumps called Merkel cells, present in most mammals but in the case of bats they are different, since each lump has a tiny hair in the center, which makes it even more sensitive and allows it to detect and collect information about the air that flows over its wings and thus being able to change its shape to fly more efficiently. Many species, such as Myotis lucifugus, take advantage of this ability to fly near the surface of the water and drink while in flight, and others, such as the flying fox (genus Pteropus) or megachiroptera, skim the surface of the water with their bodies and land nearby to lick the water adhering to the skin on their chests. The membrane of species that use wings to hunt their prey ne an additional type of receptor cell, sensitive to membrane stretch. These cells are concentrated in the parts of the membrane that insects strike with their wings when captured by bats.

Piscivorous bats have a poorly developed uropatagium, to minimize aerodynamic drag and improve their stability during low flight. Those that eat flying insects have long, narrow wings that allow them to fly at over 50 km/h. When large concentrations of insects are encountered, they sometimes only have to fly with their mouths open to capture their prey, similar to how cetaceans feed on krill. In contrast, those that eat insects located on the bark or leaves of trees have large wing surfaces that allow them to fly slowly and smoothly through dense vegetation.

Their wings also serve as protection when the animal is at rest, as well as a thermal regulator; they isolate the animal's body from the outside environment to conserve heat (to which the blood circulates through them also contributes), but they also serve to reduce the animal's temperature while it flies (this blood that circulates through the capillaries of its thin wings cools with their movement).

Not all bats have flight as their only mode of locomotion. Some, like the New Zealand mystacinids, have the ability to hide their wings under a tough membrane, an adaptation that allows them to move and feed on land, and even burrow in the ground.

There was some scientific consensus that bats evolved from flying squirrel-like gliding ancestors. However, bat flight is a highly complex functional system from a morphological, physiological, and aerodynamic perspective, and the transition from gliding to flight requires a significant series of adaptations, and recent studies suggest that bat evolution it is not related to gliding mammals.

Echolocation

Ultrasonic (red) emissions that reach the object (blue) and are reflected in the form of echo (green), returning to the bat, which calculates the distance (r) based on the time between the emission and the reception. The address is deduced by the difference between the arrival of the echo in the right and left ear.

Investigating the ability of bats to fly and capture insects in the dark, Lazzaro Spallanzani discovered in 1793 that they became disoriented if they could not hear, but avoided obstacles when blinded. In 1920 the English physiologist Hartridge pointed out the possibility that they could locate and capture their prey by hearing. As early as 1938, with the development of a microphone that picked up high frequencies, Donald Griffin discovered that bats emit ultrasound.

Bats, like dolphins or sperm whales, use echolocation, a perception system that consists of emitting sounds to produce echoes that, on their return, are transmitted to the brain through the auditory nervous system and helps them to orient themselves, detect obstacles, locate prey or for social reasons; it is a kind of biological "sonar". They use it mainly to capture their prey and provide them with information about its size, speed and direction.

Microbats emit ultrasound by contractions of the larynx, which is proportionally wider than in other mammals. These sounds can vary in frequency, rhythm, duration, and intensity. They are emitted through the mouth or nose and are amplified by "nasal blades". Different species emit different frequencies. Humans can perceive up to 20 kHz, but bats emit from 15 to 200 kHz. Frequencies can be constant (they do not change during the duration of the signal) or modulated (they vary to a greater or lesser extent). The calls may end suddenly or gradually, depending on the species. Megadermatids, phyllostomids, nicteriids, and some vespertilionids use weak intensities, while the genus Nyctalus has very loud calls that can be heard from a much greater distance. familiar or well-known places, perhaps to avoid discovery by certain predators.

During the search for prey, they emit an average of 4-12 search signals per second at irregular intervals; when they locate a possible prey, during the chase the rhythm of the signals increases significantly (up to 40-50 per second), and just before capturing them they emit a "final buzz" consisting of a sequence of 10-15 short pulses separated by an interval minimum. The entire sequence of locating, chasing and "final buzz" lasts less than 1-2 seconds.

They use their ears to hear their own echo, and those of some groups, such as rhinolophids, can move independently of each other. They calculate the distance from the prey by the difference in time between the emission of the sound and the reception of the echo, and the direction is deduced by the difference between the arrival of the echo at the right and left ears. The auricle of bats is adapted to the type of flight of each species; the faster they fly, the shorter the ears. The auricle of the two species of the genus Mormoops is one of the most sophisticated among mammals.

With very few exceptions, such as the genus Rousettus which only lives in caves and which is the only one of the suborder that produces authentic echolocation sounds to be able to move inside in complete darkness, or as Rousettus aegyptiacus which has a rudimentary form of it, megachiroptera (which feed on fruit juice, nectar and pollen) lack this ability, and use sight and smell to orient yourself.

There are studies that show that in flights through obstacles consisting of wires of different diameters stretched vertically, bats were able to avoid wires with a diameter of 0.065 mm, and that even in those of 0.05 mm the percentage of flights without collisions was very high. However, despite this accuracy and the fact that echolocation allows bats to navigate and hunt in low-light situations or even in total darkness, it also poses significant disadvantages with respect to visual perception, such as the energy cost for its production, the response time in the reception of the echo compared to the continuous perception of vision images, a limited sound field compared to the visual field of mammals, its limited range (generally less than 20 m and with a maximum of 50-60 m) or the low resolution of the "images" it produces.

Echolocation is a system that is based on the analysis of echoes; This implies that bats have adaptations both to emit signals (in the larynx) and to receive them (in the auditory system).

Adaptations in the larynx: In bats this organ is a very rigid structure, since the arytenoid cartilages are fused at their upper ends creating a single structure. The lateral cricoarytenoid musculature can rotate the arytenoid cartilages along their axes toward the midline. The intensity of the echolocation pulses emitted by a bat can reach 100 dB, and they originate from the accumulation of air under the glottis, which creates a subglottic pressure that increases the force of air output upon expiration. To minimize energy expenditure, the bat emits the ultrasonic signal on the expiration that accompanies the flapping of the wings.

Adaptations in the auditory system: in bats, hearing works and is structured in a very similar way to that of other mammals; however, there are changes in the shape and size of the ear and the tragus that are related to the ability of bats to perceive the echoes of their prey or objects. It also highlights the high sensitivity of the organ of Corti in the inner ear, which receives the stimulus from the echoes and sends the signal to the brain for later interpretation depending on the environmental conditions and the type of sound emitted.

The so-called hunting buzz is a group of short, rapidly emitted echolocation pulses that are emitted by bats before making physical contact with their prey. Upon detecting it, the bat approaches it, as it gets closer, the time interval of the pulse emission decreases in order to reduce the return time of the echo. In this way, the bat receives more detailed information on its trajectory, in order to follow or intercept it. Bats using FM-FC signals when locating prey can gradually convert the pulses entirely to constant frequency (FC) to receive detailed prey information. At first these sweeps (changes) are of a wide frequency range or bandwidth, but as the bat gets closer to the prey, the FM (frequency modulated) sweeps become shorter as the bat each time is getting more detailed information about it.

Ecology

They occupy niches in all habitats except polar regions, oceans, or the highest mountains. Most are insectivorous, but have a very wide variety of diets; some specialize in a relatively narrow range of foods, and others are omnivorous. Almost all bats eat at night and rest during the day, in very varied places depending on the species, such as caves, buildings, holes, cracks or outdoors. Some species are solitary, but others, such as the mouse-tailed bat (Tadarida brasiliensis), form colonies of 20 and up to 50 million individuals in some caves in Texas and the northwestern United States, which consume between 45 and 250 tons of insects each night. Bats are viviparous, and many species have evolved complex reproductive physiology.

Life Cycle

They typically reach sexual maturity at twelve months, and mating systems vary from species to species. Some bats are promiscuous, congregating in large groups in one or more trees and copulating with several nearby mates. Many Neotropical microbats maintain and defend small "harems" of females. Although most species are polygynous or promiscuous, some, such as Vampyrum spectrum, Lavia frons, Hipposideros galeritus, Nycteris hispida and several of the genus Kerivoula, are monogamous and, in these cases, the male, the female and their offspring live together in family groups and the males can help protect and feed the young.. Courtship behavior is complex in some species, while in others it can be almost non-existent, reaching the case of males of some species that mate with hibernating females that hardly react to copulation.

A large number of species breed seasonally; those from temperate zones often do so before initiating hibernation. All species that are not seasonal breeders occur in the tropics, where resources are often relatively constant throughout the year. The function of seasonal breeding is to coordinate reproduction with the availability of resources that allows the survival of newborns. Vampire bats can hatch at any time of the year.

Bats are viviparous, generally with a relatively slow embryonic development (3-6 months), the length of gestation can vary depending on food availability and climate, and from one species to another can vary from forty days to ten months. Many species have developed a complex reproductive physiology, such as delayed ovulation, delayed implantation, sperm storage, delayed fertilization, or embryonic diapause. Delayed ovulation occurs primarily in bats from temperate zones, and implies that they mate in late autumn and that the female stores the semen throughout the winter; ovulation occurs in spring so that the young are born in summer, when plenty of insects are available. In the case of delayed implantation, the embryo begins to develop immediately but stops shortly after, waiting for conditions to become favorable again; This type of embryogenesis occurs in African megabats and in the genus Miniopterus and in other species, such as Macrotus californicus, the ovule is implanted but the fetus does not develop until the spring. They can also lengthen gestation to avoid bad weather; in tropical areas, they can do it to wait for a better time in terms of weather or food availability. Migration and hibernation also limit the optimal mating season.

Females generally give birth to one pup per litter (although sometimes there can be two) and one litter per year, however some species of the genus Lasiurus, such as the reddish boreal bat (< i>L. borealis) from North America, can have three or four young. In northern Europe, pipistrels have one calf, but in more southern areas they usually have two, and taking into account that twins are more frequent among well-fed captive specimens than among the same species in the wild, probably a better nutrition influence the number of births.

At birth they already have between 10 and 30% of the weight of their mothers, who need a great energy supply to produce milk for their young. Newborns are completely dependent on their mothers for both protection and food, even in the case of pteropods, whose young are already born with fur and open eyes; microbats tend to be more altricial at birth. In some species the young are born with the mother hanging upside down and in others she turns her head up and picks up the young with the interfemoral membrane (skin membrane that extends between the lower limbs and upper limbs). The tail). In most species, the females have two breasts on the chest, in some they have another pair of false inguinal breasts that are used for the young to hold onto and in others, such as Lasiurus, there are four functional breasts; lactation can begin within minutes of birth.

Species from temperate zones generally form maternity colonies, a kind of nursery made up almost exclusively of adult females; these overcrowding reduce heat loss and energy expenditure of each individual. Most bats, especially insectivores, which need maximum maneuverability, leave their young on their perches while they feed and usually only carry them with them when they change roosts. The young of small species develop quickly and fly in 20 days, while the larger flying foxes can take three months to start their first flight; vampires are the slowest to develop, nursing for up to nine months. Although they generally reach their maximum body weight a few weeks after weaning, some species may take several years to achieve this.

The average lifespan of bats is usually four or five years, although they often reach ten to twenty-five years, and some species can live thirty years of age. Mammalian longevity is generally related to their size, so bats live surprisingly long in proportion to their size, typically about three and a half times longer than other mammals of a similar size..

Distribution

They are found all over the world, except for the polar regions, the highest mountains, particularly isolated islands (mainly in the eastern Pacific), oceans, or the center of the largest deserts; they occupy niches in all habitats and their ability to fly allows them to colonize new areas, if they have resting and food perches. In New Zealand, Hawaii, the Azores, and many oceanic islands, they are the only indigenous mammals. Along with rodents, they are the only eutherian taxon to colonize the Australian mainland without contribution from humans, where they are represented by six families. They probably came from Asia, and have only been present in the fossil record for fifteen million years. Although 7% of the world's bat species live in Australia, there are only two endemic genera on this continent.

Some species are migratory and although they generally do not migrate long distances, they can travel as long as the one that separates northern Canada from Mexico.

They have colonized a wide variety of habitats. They live underground, in cracks and fissures in rocky walls, among leaf litter, behind the bark of trees, or in their cavities. As for human constructions, bats also live in basements, warehouses, bridges, and military constructions.

Food

The feeding habits of bats are almost as varied as those of all mammals combined, and this dietary diversity is largely responsible for the morphological, physiological, and ecological diversity seen in these animals. They feed on insects and other arthropods, fruit, pollen, nectar, flowers, leaves, carrion, blood, mammals, fish, reptiles, amphibians, and birds.

Their food preferences vary greatly between the two extant bat suborders and between the different families. The megabats only eat fruit, pollen and nectar although sometimes they supplement their diet with carrion and small birds or fish, but among the microbats there is a great variety of diets. The peculiar New Zealand bat Mystacina tuberculata is an omnivorous species, like Phyllostomus or some Neotropical species. The family Phyllostomidae has a wide variety in feeding habits and ecology and alone accounts for virtually all of the diets exploited by other bats, and also includes the only three hematophagous (blood-feeding) species.

- Insectivorous

About two-thirds of living species, including all those in temperate and cold latitudes, are solely insectivorous. The large numbers of insects make them an abundant and varied food. Given their mostly nocturnal habits, when the insectivorous birds are inactive, the bats have no competition to hunt the large number of insects that emerge after sunset. Almost all families of insects can be their prey and, although to a much lesser extent, they also feed on other types of arthropods, such as spiders, harvestmen, crustaceans, scorpions or centipedes.

The vast majority of insectivorous bats are small and capture their prey in flight; some use their wings or legs and many have a membrane between their lower extremities (uropatagium) that they use to capture insects and that is sometimes bag-shaped. To capture their prey during flight, they mainly use echolocation, and to counteract this ability, some groups of moths such as arctids produce ultrasonic signals that warn them that they are chemically protected, or noctuids have an ear organ that responds. to the signal emitted by the bats and which causes the moth's flight muscles to contract erratically, causing it to execute random evasive maneuvers, such as dropping or performing a pirouette that misleads the bats and makes it difficult for them to escape. catch.

Bats not only hunt their prey in the air, but sometimes also on the ground. prey, waiting for them in a fixed place to launch into their pursuit. The Australian false vampire (Macroderma gigas) captures large insects and small vertebrates by attacking them from above and capturing them with their feet and then carrying them to the top of a tree branch to eat, similar to how they birds of prey do.

- Frugivores and polynivores

Approximately 25% of the bat species are vegetarian, and are distributed throughout the tropical and equatorial zones of the planet. Their diet can be made up of fruits, nectar or, to a much lesser extent, leaves. The fruit bat Eidolon helvum feeds on thirty-four genera of fruits, ten genera of flowers, and four species of leaves. Hypsignathus monstrosus feeds primarily on fruit juices, although it supplements its diet with carrion and birds.

Their preferences are generally towards fleshy and sweet fruits, but not particularly scented or brightly colored. They pluck the fruit from trees with their teeth and fly to a branch or ledge with the fruit in their mouths and consume it there in a specific way; they eat until their hunger is satisfied and the rest of the fruit, the seeds and the pulp fall to the ground and these seeds take root and become new fruit trees. More than 150 types of plants depend on bats for reproduction.

About 5% are polynivorous (they feed on pollen); These species have atrophied chewing muscles and jaws compared to other bats, a long, pointed nose (which allows them to insert it into goblet-shaped flowers), and a long, raspy tongue with which they quickly lick up nectar.. Smell and taste are well developed in these bats. As in the case of insects, plants that are pollinated by bats have coevolved with them; some plants have strong stems so as not to break when bats land on them, while other bats are more delicate and take nectar in mid-flight, like hummingbirds.

- Carnivores and fish

Few species have been confirmed as strict carnivores. The term carnivore applies to bats in which small vertebrates (excluding fish) form a significant part of their diet, although there appear to be species that are exclusive, opportunistic, or occasional carnivores. Thus, Vampyrum spectrum, Trachops cirrhosus or megadermatids feed on arthropods, other bats, small rodents, birds, lizards and frogs.

Some bats are predominantly piscivorous, although, as in the case of carnivores, it is not usually their exclusive food. Among the few existing fish-eating species, such as Myotis vivesi or Myotis capaccinii, the fishing bat (Noctilio leporinus) although it also feeds on insects and crustaceans, is one of the bats best adapted for a fish-based diet. This species, the largest of the Noctilionidae family, has anatomical adaptations such as enormously elongated legs, claws, and the spur on its hind limbs, which give it highly effective in catching fish near the surface of the water; with an extremely sensitive echolocation system, these bats detect their prey by means of the turbulence produced by schools of fish at the surface of the water. Although most take freshwater fish, some species, such as Pizonyx vivesi , they feed on crustaceans and marine fish, going so far as to experience adaptations that allow them to drink salt water, something very rare among mammals.

- Hematologists

Despite the widespread popular view of bats as blood-feeding animals, there are actually only three blood-sucking species, all native to the Americas and included in the subfamily Desmodontinae. Blood-sucking bats are known as vampires.

The common vampire (Desmodus rotundus) is the most widespread; it feeds on the blood of cattle, dogs, toads, tapirs, guanacos and even seals, while the hairy-legged vampire (Diphylla ecaudata) feeds on the blood of birds. The white-winged vampire (Diaemus youngi), the rarest of these species, also feeds on the blood of birds and most of the information on it has been obtained from specimens. found in chicken coops.

When the sun goes down, vampires come out in groups of between two and six animals. Once its prey is located, like a sleeping mammal, it lands on an area devoid of hair, or close to its prey and goes to it by land; it chooses a suitable place to bite using a heat sensor located in its nose to locate an area where blood is flowing close to the skin. They do not suck or absorb blood, but rather lick it up, and their saliva plays a key role in the process of feeding on the wound as it contains various compounds that prolong bleeding, such as anticoagulants that inhibit blood coagulation and compounds that prevent strangulation of blood vessels near the wound.

The blood loss caused by their bites is relatively small (about 15-20 ml), so the damage caused to the prey is also small. The greatest risk to their prey from these bites is associated with their exposure to secondary infections, parasites, and the spread of diseases transmitted by viruses such as rabies. Rabies occurs naturally in many wild animals, but it is much more common in skunks or foxes than in bats, and since vampire bites of humans are very rare, transmission of this disease to humans is very rare.; even so, considering that vampires can carry this virus, they should be handled with caution.

Hibernation

Bats that live in temperate zones suffer in winter, not only from low temperatures, but also from the scarcity of their prey (mainly insects). Most do not migrate, but sleep until spring in a state called hibernation. In this state, a series of physiological changes occur that allow a drop in body temperature and a general decrease in metabolic functions to prolong the duration of energy reserves; their duration is longer the closer they are to the poles (the most extreme last up to six months, while the mildest are short and intermittent). Many other mammals hibernate, such as bears (carnivores), squirrels and dormouse (rodents) or hedgehogs (erinaceomorphs), but none to the degree of many bat species, as most hibernating mammals drop their normal active body temperature to less than 10 °C, while some bats drop below 0 °C (up to -5 °C in the case of the reddish boreal bat).

During the fall or late summer they eat large amounts of food to build up reserves and gain weight rapidly, mostly in the form of subcutaneous fat that is stored on the shoulders, neck and flanks, where it forms visible lumps, and that can represent up to a third of your body mass; if they don't build up enough reserves, since they can't feed again until spring, they could starve. The change in habits from summer to winter is sudden, and is caused by one factor or a combination of factors such as the availability of food, the outside temperature, or the length of the day. The vital functions are diminishing and the metabolism decreases; the heart beats only ten times a minute, in contrast to the 600 beats during summer hunting; breathing is so faint that it is almost imperceptible and only accounts for 1% of breathing in the active phase, reaching several minutes without breathing; body temperature falls and equalizes with ambient temperature (0-10°C). Each species has a preferred temperature, and the lower the body temperature, the longer their energy reserves will last; however they must avoid freezing, and low temperatures can be dangerous and have negative effects such as reduced resistance to disease.

Bats in this state wake up periodically, to urinate and defecate in order to eliminate excess water and waste products, toxic to tissues, and restore physiological balance (homeostasis), or to move to another place. Some bats wake up every ten days, while others may take ninety; dormant periods tend to be longest early in hibernation. They choose places like caves, mines, tree cavities, cracks or even exposed places; it is important that they choose locations with high humidity (usually above 90%), to avoid excessive evaporative losses, which would force them to wake up more frequently to drink and to prevent their wings from drying out (i.e. particularly important for horseshoe bats, which hang in exposed places draped in their wings). Some species that sleep in caves do so alone or in small groups, but others form groups of tens and hundreds of thousands, or even millions of individuals, with concentrations of more than three thousand individuals per square meter. In some cases it is It is possible to find numerous species sharing the same cave permanently or temporarily.

Hibernating bats can also become torpid at any time in the summer, especially in cold climates when food is scarce. This summer torpor is not as extreme as hibernation; they also accumulate food reserves when food is plentiful and enter a certain torpor when it is scarce. Its body temperature is around 30 °C, much higher than during hibernation.

Predators

In general, bats have few natural predators, limited to some birds of prey, carnivorous mammals, snakes, and large lizards.

Particularly in the tropics, boas and snakes attack flying foxes hanging from branches; these snakes climb the trees and capture them by surprise while they rest, especially the young. When the attacks of these reptiles are repeated, they can cause a great impact in some populations by leaving them without young. On the other hand, the snakes that hunt in the caves do not seem to have bats among their usual prey, and only attack them sporadically. Some large tropical lizards also eat bats.

The bat kite is a bird of prey that hunts bats, attacking them when they emerge at twilight. They are also hunted by the Common Kestrel, Eurasian Hobby, and Peregrine Falcon, but the greatest avian danger to bats is nocturnal raptors, such as barn owls and owls, which wait outside burrows for dusk to catch. to the bats that come out. Owls clip their wings before eating them. Some birds have learned to adapt to the habits of bats, attacking them when they are looking for insects. However, in the vast majority of cases they only represent 0.1-0.2% of the prey of birds of prey.

Some opportunistic carnivores, such as boreal raccoons, skunks, bobcats, and mustelids, actively hunt bats, while European badgers and foxes only eat hatchlings that have fallen off the roof of a cave or have chosen to escape. hangers at too low a height; however, bats are unusual prey for these animals. Also some rodents, such as the field mouse, occasionally feed on bats, as well as other animals such as mygalomorphic spiders, some carnivorous fish and some large amphibians such as the bullfrog.

However, species introduced by humans can decimate their populations. Thus, due to the introduction of the brown tree snake (Boiga irregularis) in Guam, between 1984 and 1988, all the young of some bat species were eaten before reaching adults; a similar situation occurred with the introduction of the Indian wolfsnake (Lycodon aulicus capucinus) to Christmas Island. The cat, another introduced species, is one of the most dangerous predators for the bats; some cats become feral and specialize in hunting bats, being able to exterminate an easily accessible and not very large colony in a matter of days. Some bats fight or play dead to defend themselves.

Threats and conservation

Bat populations are declining rapidly around the world, and several species have recently become extinct. Of the 1,150 species listed on the IUCN Red List, just over half are listed as Least Concern and for some two hundred there are no data available for their classification, but seventy-seven are listed as near threatened, ninety-nine as vulnerable, fifty-three are in danger of extinction, twenty-five are critically endangered, and five are already extinct (Desmodus draculae and four members of the genus Pteropus: P. brunneus, P. pilosus, P. subniger and P. tokudae).

White nose syndrome has killed more than a million bats in the northeastern United States in less than four years. The disease is named for a white fungus found growing in the snout, ear, and wings of some bats, but it is not known whether the fungus is the primary cause of the disease or simply an opportunistic infection. A mortality rate of 90–100% has been observed in some caves. At least six overwintering species have been affected, including the endangered Myotis sodalis. Because affected species have long lifespans and low birth rates (approximately one offspring per year), it is believed that populations will take time to recover.

Threats of anthropogenic origin include mercury poisoning and wind turbines, a means of producing clean and renewable energy, but which cause a high mortality rate among bats; taking into account that signs of external trauma are often not appreciated, it is assumed that their high mortality in the vicinity of these devices is due to a greater sensitivity of their lungs to sudden fluctuations in air pressure and that, unlike those of birds, it makes them more likely to break. On the other hand, in the dark they mistake wind turbines for trees and are injured or killed by their blades, or get caught in the air vortices generated by their rotation. Although various studies indicate While some species have adapted to feeding in open spaces on insects attracted to mercury vapor lamps, recent work shows that light pollution t It has a strong negative impact on species such as the lesser horseshoe bat (Rhinolophus hipposideros) and other slow-flying nocturnal bats, as it prevents them from selecting suitable flight routes to their feeding grounds and thus affects drastically to the growth of the young, and flying in illuminated areas makes them more vulnerable to their predators. To all of the above must be added the deaths from being run over by cars, trucks or trains, a mortality that has not yet been quantified but that is probably elevated.

For centuries, large frugivorous flying foxes have been hunted for meat in small numbers in Africa, Southeast Asia, and on islands in the Indian and Pacific Oceans; However, with the increase in firearms and the ease of accessing their habitats, this resource has been overexploited and many species are in danger of extinction, which, due to its importance in pollination and seed dispersal, has an important impact on crops and a great impact on the development of tropical forests and savannahs. Cave bats are particularly vulnerable, as caves often only have a small entrance through which all the animals must pass and if hunters station themselves at their entrance they can easily kill large numbers of bats; Added to this is the problem of by-catch (capture of species other than the one intended to be hunted), as in the case of the small insectivorous bat Tadarida plicata of Thailand, which forms colonies of more than one million individuals in some caves and where the local inhabitants have collected their guano for two hundred years, but which coexists with frugivorous bats that hunters now capture to sell their meat by setting up nets at the entrances of the caves, and at the same time they capture T. plicata, which are killed in large quantities and then discarded, which, in addition to reducing the population of both species, has affected the production of guano used by local farmers.

In temperate regions, the main causes of declines in bat populations are habitat loss and killings, deliberate or accidental. The collection of bat guano is a problem for these animals, as it disturbs their roosting sites, and when regularly disturbed during their hibernation they starve and many roosting sites, such as caves and hollow trees, have been obstructed or felled. The proliferation and intensive use of insecticides represent a threat to insectivorous bats. In addition to a large reduction in the size of the insect populations, which are their food, pesticides can cause indirect poisoning of bats when they eat intoxicated prey. Insecticides are not widely used in the developed world anymore, but in developing countries they are still widely used, and the lack of regulation means that highly toxic insecticides are often used.

Some species are persecuted because they feed on agricultural crops, or because they are vectors of diseases, and the Ministries of Agriculture of some countries consider some bats as pests and recommend their extermination or the reduction of their numbers. However, organizations such as Bat Conservation International, an organization dedicated to collecting data on the status, distribution and threats facing them, organizes educational programs and promotes research and conservation. Also myths, superstitions and mistrust towards these animals have often impeded the development of protection programs. However, currently international agreements have been signed for their conservation and bats are protected by the laws of most European countries and many others, and resting places and feeding habitats are being designated to promote their conservation.

Systematics and phylogeny

Systematics

|

Bats were previously grouped in the superorder Archonta along with scandentians (Scandentia), dermopterans (Dermoptera), and primates (Primates), due to apparent similarities between megabats and these mammals. Currently, genetic studies have placed bats in the superorder Laurasiatheria, along with carnivores (Carnivora), pangolins (Pholidota), Eurasian and American insectivores (Eulipotyphla), perissodactyls (Perissodactyla) and cetartiodactyls (Cetartiodactyla, order of placental mammals that brings together the ancient orders of cetaceans and artiodactyls).

The classification of the current bats according to Simmons and Geisler (1998), with the modifications suggested by Kirsch et al. (1998), divides them into two suborders with eighteen families:

Order of Bats (Chiroptera) Blumenbach, 1779

- Suborden (Megachiroptera) Dobson, 1875

- The mega-shoulders, known as "flying foxes", contain a single family, Pteropodidae Gray, 1821. Pteropods include larger bats, their diet is exclusively vegetarian (frugivores or nectar) and live in the tropical and subtropical regions of Africa, Asia and Oceania. An example of this suborden is the flying fox of India (Pteropus giantusor the Filipino flying fox (Acerodon jubatusThe greatest bat in the world. From an evolutionary point of view, the mega-shoulders are the bats closest to the primates, and therefore to humans. They are characterized by their great eyes, their muzzle, reduced uropatagio and the presence of a claw on the second finger of the previous limb. The great flying fox (Pteropus vampyrus) has a size of 170 cm, the largest among the operating rooms. The species of this suborden lack ecolocalization (except Rousettus aegyptiacus which has a rudimentary form of this capacity), so they depend on their eyes and have a very developed and colored night vision.

- Suborden (Microchiroptera) Dobson, 1875

- Superfamily Emballonuroidea

- Emballonuridae Family (Gervais, 1855). Embaloneides live in tropical and subtropical regions around the world. This family has some of the smallest species in the world, with a body size ranging from 3.5 to 10 centimeters in length. They tend to be brown or gray, though those of the genus Diclidurus They're white. They have a short tail that is projected by the flow membrane forming a pod. Most species have sac-shaped glands in the wings, which are open and can serve to free pheromones to attract a couple. Other species have glands in the throat that produce secretions of a penetrating odor.

- Superfamily Molossoidea

- Antrozoidae Family (LeConte, 1856). It only has a species, Antrozous pallidus. Its distribution range goes from western Canada to central Mexico. It has bigger eyes than most of America's O.R. species and its ears are pale, long and wide. His coat usually has a clear tone. It measures between nine and thirteen centimeters long and feeds on arthropods as crickets and scorpions. Some authorities include Antrozous spp. within the Vespertilionidae family (Antrozoinae subfamily).

- Molossidae Family (Gervais, 1856). The molósidos, or “cold bats”, are widespread and live on all continents except Antarctica. In general they are quite robust, very suitable flyers and have relatively long and narrow wings. Controlled by the action of the muscles, a special cartilage ring slides up and down the flow vertebrae to stretch or remove the membrane from the tail, which gives these species a precision in flight manoeuvres comparable to that of the swallows and the victories. The molosides are the fastest bats.

- Superfamily Nataloidea

- Furipteridae Family (Gray, 1866). Furiptéridos, known as "furia aladas", live in Central America and South America. To this family only belong two genera and two species that are characterized by their small thumbs (almost absent) and function follies, surrounded by the elar membrane and by their wide ears in the form of funnel. They are insectivorous and live in different types of media. They have a gray coat and a small nostril.

- Myzopodidae family (Thomas, 1904). The mizopods are made up of two endemic species of Madagascar and of which there is little information. Both belong to the gender Myzopoda, and its most outstanding feature is the presence of suction cups on the wrists and ankles that allow them to easily attach to the smooth surface of the leaves.

- Natalidae Family (Gray, 1866). The Natalids live in Central America, South America and the Caribbean islands. Known as "pathy bats" or "sleep ears", they are slender, with an unusually long tail, a short and triangular drink and with large ears in the form of funnel. They are small, with a size of only 3.5-5.5 centimeters, and with a brown, gray or reddish coat.

- Thyropteridae Family (Miller, 1907). Tyroleans live in Central America and South America, from Honduras to Peru and Brazil, often in humid tropical jungles. They only have a genus, with three species. Known as "snare bats" because like the mizopods, they have suction cups on the wrists, ankles and functional thumbs that help them to stick to smooth surfaces such as banana leaves or Heliconiaunder which they protect themselves from the rain and hide from their predators. They feed exclusively on insects.

- Superfamily Noctilionoida

- Mormoopidae family (Saussure, 1860). Mormophoids are typical of Central America and South America and are distributed from southern Mexico to southeastern Brazil. They are characterized by the presence of a foliform development on the lips, instead of the nasal foliform typical of most bat species and have a strip of stiff hairs on their snouts, hence their common name of "mous bats". In some species the elar membrane joins on the animal's back, which makes them look bald, but under the wing they have a normal layer of skin. The tail only projects a short distance beyond the membrane that extends between the later legs. They live in caves and tunnels in huge colonies that can include hundreds of thousands of individuals, and produce enough guano to allow their commercial exploitation. Don't hibernate.

- Mystacinidae Family (Dobson, 1875). Mistacids are made up of two rather atypical endemic species of New Zealand and adjacent islands. Known as “collective bats”, they spend much of the time on the ground, instead of flying, and have the unique ability to fold the wings when they do not use them. The nails of the thumbs and fingers of the feet have a projection, unique among bats, that helps them run, dig and climb. Separate and simple ears with a long drink, and partially extendable tongue, with papills on your tip. They are omnivores who feed on fruit and carrion, as well as arthropods who hunt on the ground; they also eat pollen and nectar, which can collect with their extended tongue. Sometimes they build their hole in trunks in the process of rotting, but they also nest in cracks in rocks or nests of seabirds.

- Noctilonidae Family (Gray, 1821). Noctilionides only include a genus and two species, which are distributed from Mexico to Argentina. They live near the water and are known as "fisher bats", although they are mostly insectivorous and only Noctilio leporinus usually supplements your diet with small fish, using ecolocalization to detect your movements in the water; you can hunt between twenty and thirty fish in one night only.

- Phyllostomidae Family (Gray, 1825). The philtomides live in Central and South America and are the most varied and diverse family of aeropters. They are often referred to as "lance vampires" because many of their species have a foliform appendix as a spear; they have a fleshy protuberance in the nose that has a size that goes from occupying almost the head in some species, to complete absence in others, and many species also have carnosities, warts and other protuberances in the head near this protuberance or in the barb. Although mainly insectivorous, the members of this family have evolved to serve various types of food, such as fruit, nectar, pollen, insects, frogs, other bats and small vertebrates or, in the case of vampires, blood. The sounds used for echolocation are emitted by the nose. They do not hibernate, but some species stivan (enter a sopor state with high temperatures and drought).

- Superfamily Rhinolophoidea

- Megadermatidae Family (H. Allen, 1864). The mega-degree live from central Africa, across India and South Asia to the Philippines and Australia. They are known as "false vampires". They are relatively large, with a length of 6.5-14 cm. They have very large eyes and ears, a prominent nasal foil and a broad membrane between the later legs (uropatagio), but lack tail. Many species of this family are of a matt brown color, but some are white, of a blue grey or even olive green, which helps them to camouflage in their midst. They are mainly insectivorous, but supplement the diet with a wide variety of small vertebrates.

- Family Nycteridae (Van de Hoeven, 1855). Nictérides have a single gender, Nycteris. They speak in Malaysia, Indonesia and some parts of Africa. Its average length ranges between 4 and 8 cm, and its fur is greyish, brown or red. They are referred to as "hole bats" or "cut face", because they have a deep fold or pit in the center of their face, between the eyes, which could be related to echolocation, with the windows of the nose to the tip of the snout. They have long ears and small drink, and a T-shaped tail, unique feature among mammals. They have several periods of estro and give birth twice a year.

- Rhinolophidae Family (Gray, 1825). They are distributed by the Old World, especially in the tropics; some species in temperate Europe, Asia and Japan. Known as "sandlar bats", all rhinoceros have their nose surrounded by fleshy protuberances, which may have a shape of horseshoe, a saddle or a lancet. Most are small. Ears are generally large, broad at the base, end up on the tip and can move separately; they lack a drink, but the antitragus is well developed. The eyes are small and the broad and rounded wings. The tail is short and is completely included in the elar membrane; it is attached to the loin when the animals are at rest. Undeveloped rear legs, unable to walk on four legs. Like the flying foxes, and unlike most bats, the heads of these bats point down (ventrally). They usually embark on the flight by dropping down, but they can also start the flight from the ground. When landing they make a 180° turn on their axis.

- Superfamily Rhinopomatoidea

- Craseonycteridae Family (Hill, 1974). Known as "swine nose bats", the craseonictérides only have one species, the murciélago flyrdon (Craseonycteris thonglongyai). With a size of 30-40 mm, it is the smallest mammal in the world in terms of length (in terms of weight, the etruscan musarain (Suncus etruscus) is lighter, although the difference is minimal. It is a very rare species and IUCN is listed as vulnerable, partly due to the impact of tourism and the collection of guano in its habitats of bamboo forests and teak plantations in Western Thailand and Myanmar. They live in caves forming groups of less than 20 individuals, feed on insects and spiders and hardly know their reproduction and ecology, and have not discovered fossils of this species.

- Rhinopomatidae Family (Bonaparte, 1838). The rhinos, known as "mouse tail bats", include a single genus with three species. They live in the Old World, from North Africa to Thailand and Sumatra, in arid and semi-arid regions. They nest in caves, houses and even in the pyramids of Egypt. They are relatively small, with a length of only 5-6 cm. Its common name is due to its long tail, which stands out almost entirely from the long membrane, and almost as long as the body, unique case among the current insectivorous bats.

- Superfamily Vespertilionoidea

- Familia Vespertilionidae (Gray, 1821). The vespertilionides contain almost one third of the living bat species, with five subfamilies and more than 300 species currently recognized. With the exception of polar regions and some remote islands, they can be found all over the world and live in tropical forests, deserts and temperate areas. They've got the sniffy muzzle, no nasal lobes. The ear has a drink and the eyes are small. The queue is fully or almost entirely included in the uropatagio and rest is bent in the abdomen. The color of the coat is dark (black, brown or grey) but the abdomen is clearer. Given its breadth, this family has a wide variety of sizes; some weigh only 4 grams, while others weigh up to 50 grams.

- Superfamily Emballonuroidea

In the work Mammal Species of the World eighteen families are also cited, but they do not include Antrozoidae and instead mention Hipposideridae, previously considered a subfamily of Rhinolophidae, but returned as a family by Corbet and Hill (1992), Bates and Harrison (1997), Bogdanowicz and Owen (1998), Hand and Kirsch (1998) and many other authors. The Integrated Taxonomic Information System (ITIS) recognizes seventeen families, those mentioned above but not including or Antrozoidae or Hipposideridae.

In addition, Simmons and Geisler describe in 1998 several extinct families of bats, which corrected and augmented by Smith et al. in 2007 and Simmons et al. in 2008 are:

- Family Onychonycteridae †

- Clado Microchiropteramorpha † (inc. sed.)

- Gender Jaegeria†

- Family Icaronycteridae †

- Family Archaeonycteridae †

- Palaeochiropterygidae Family †

- Hassianycterididae †

Phylogeny and evolution

According to more recent phylogenetic studies, within the Scrotifera clade, the basal group is the Chiroptera.

Regarding their evolution, based on morphological reasons, Chiroptera had long been misclassified in the superorder Archonta (along with primates, dermoptera, and scandentians) until genetic research showed their close relationship to laurasiateria (which contains the clade Scrotifera, which unites the order Chiroptera with the orders Carnivora, Artiodactyla, Perissodactyla and Pholidota); this despite the fact that there are few anatomical similarities within said clade and it seems that they are not related.

Regarding fossils, fossils of bats with more primitive characteristics have been discovered, being Onychonycteris finneyi the most primitive species of the two oldest monospecific genera of bats on record. This species lived in an area that is now the state of Wyoming during the Eocene period, 52.5 million years ago, succeeding Icaronycteris index, previously considered the most primitive bat species. The first bats to appear in the fossil record were already flying and feeding on insects. Their morphology was very similar to today's, but echolocation was not yet available, as evidenced by O's underdeveloped cochlea. finneyi. They are thought to have evolved from small arboreal mammals that jumped from tree to tree, first developing membranes for gliding and eventually wings. However, no fossils representing an intermediate stage have been discovered. of this evolution. The two suborders of Bats, Megabats and Microbats, diverged near the beginning of the Cenozoic.

During the Oligocene, when the configuration of the continents was different from today, South America was isolated from the rest of the land masses and the Australian continent was further south than it is today. In this geographical situation, their ability to fly allowed bats to expand much more than other groups of mammals. Twenty-three million years ago, they colonized Indonesia and Australia.

In the Pleistocene, global temperatures plummeted, creating vast polar caps in both hemispheres. Those that did not migrate to lower latitudes died. Population genetics shows that European bats took refuge in the southern European peninsulas (Iberian, Italic and Balkan).

During this time they shared caves with primitive humans, however almost nothing is known about this encounter between species; cave paintings of bats have only been found in caves in northern Australia.

Relationship with the human being

History of his studio

Aristotle did not know if bats were birds or some other type of animal. Three centuries later, Pliny the Elder considered them birds, an error that persisted for almost all naturalists until the 16th century. For Conrad von Gesner they represented an intermediate form between birds and mammals. Finally Linnaeus ended up classifying them as mammals in his famous Systema naturae , ordering them in a common trunk with primates and man. Soon after, Daubenton had already described five of the bat species that inhabit Europe.

In early works, legends were mixed with science, and they were full of inaccuracies. However, Buffon already discovered the hibernation of bats, and during his exploration of caves he found caverns full of bat guano; Observing that there were remains of flies and butterflies in the droppings, Buffon began to learn about the diet of European bats.

At the beginning of the 19th century it was already widely accepted that bats formed their own order. European naturalists received specimens from all over the world, sent by pioneers of the age of exploration. Many specimens came from exotic countries, and neither the distribution nor their behavior was known. Specimens were often received by naturalists without any indication of their origin. the behavior of bats, and hibernation and awakening (Brehm) or the shape of their wings (Blasius) was already studied. In addition to field work, laboratory research was carried out, with bats in cages fed with bat worms. flour and flies. In this way, details about mating, childbirth, or delayed ovulation were discovered.

With the arrival of the XX century, the banding technique began to be used for its study. The rise of speleology also allowed us to better understand cave-dwelling bats, although it also implied a disturbance of their habitat. Some of the techniques developed during this century were very cruel; Hibernating animals were caught (awakened in the process), studied, and then released back into the cold, where they died. Those in charge of their capture also used to put a large number of specimens in a very small space, causing them to die by drowning or to injure themselves trying to flee, and the inexperience of some capturers caused them to fracture their forearms or fingers. For this reason, some capture and study campaigns caused tens of thousands of bat deaths and the loss of entire colonies. In the early 1960s, some biologists began to oppose this methodology.

Early naturalists could not understand how bats could "see" in the dark. Investigating the possibility that it was a sense other than sight, some naturalists covered their eyes and released them in dark rooms with many obstacles and verified that the animals did not crash into the obstacles, however when they injured their ear canals or covered them with wax, the bats became disoriented. At the end of the 18th century, Spallanzani and Jurine began to investigate this phenomenon in the laboratory. Cuvier hypothesized that their ear and wing membranes were highly sensitive, detecting changes in the air. Boitard believed that this perception was related to hearing, and Allen suspected that the tragus, a lobe of skin in front of the pinna of bats, picked up return signals, just like sonar.

In 1938, with the development of a microphone that picked up high frequencies, Donald Griffin and Robert Galambos of the Harvard Medical School Laboratory conducted experiments to confirm that bats use echolocation. Working with different species of bats, they discovered their ability to send and receive ultrasound up to 50 kHz. In 1940 they presented their discovery.

Benefits for men

The role played by bats in maintaining and regenerating forests, dispersing seeds, or acting as pollinators or pest control agents is increasingly supported by arguments provided by numerous scientific studies.

Bats can be useful as biological control agents, reducing or limiting the growth of populations of insects or other arthropods that might otherwise become pests. In this way, they indirectly protect humans and other animals from diseases transmitted by insects, and prevent their uncontrolled growth from endangering vegetable plantations. There are recent studies that indicate that they contribute decisively to pest control, such as the one carried out by Cornell University, which recommends that farmers try to increase local populations of bats and swallows between May and July, when they can have the greatest effect on insect populations. Another study published in 2008 in the journal Science revealed that bats were significantly more efficient than birds in biological control tasks; plants with no access to birds had 65% more arthropods than control plants, while plants with no access to bats had 153% more. According to this study, bats also protect plants from herbivorous animals to some extent.

They play a vital ecological role as pollinators. There are about 750 species of plants pollinated by different bats around the world. A bat can visit up to 1,000 flowers in one night. A bat is capable of carrying pollen from one flower to another 30 kilometers away, and flights of 65 km in one direction in a single night have been recorded.

They also play an important role in seed dispersal. When they eat a fruit, which they later excrete elsewhere, they help the plant spread to new areas. Many tropical plants are completely dependent on bats.

Their role in disease transmission

Bats are a natural reservoir for a large number of zoonotic pathogens such as rabies, severe acute respiratory syndrome, Henipavirus and possibly Ebola virus. Their high mobility, wide distribution, and social behavior make bats hosts and vectors of disease. Many species also appear to have a high tolerance for harboring pathogens and often do not develop disease while infected.

In regions where rabies is endemic, only 0.5% of bats carry the disease, yet according to a report in the United States, 22 of 31 human rabies cases were not caused by dogs between the 1980s and 2000s, they were caused by bat bites.

There is evidence of several human deaths in the jungles of South America after the attack of large groups of bats due to the rabies virus transmitted by their bites, forcing the health authorities to apply preventive and control measures, such as vaccines and anti-rabies serum, to protect native populations where there were outbreaks of this disease; these attacks are caused by changes in local ecosystems, such as indiscriminate deforestation that causes the extinction of some species that are natural predators of bats and others that serve as a source of food and, in the case of blood-sucking bats, the transformation of the tropical forest into pastures for livestock initially increases their volume of food, which facilitates their reproduction and the increase of populations, but later the constant movement of the cattle in search of new pastures leaves them without a source of food.

Rabid individuals are often clumsy, disoriented, and unable to fly, making them more likely to come into contact with people. Although you should not have an irrational fear of these animals, it is advisable to avoid handling them or having them in inhabited places, as with any wild animal. If a bat is found in a residence near a sleeping person, infant, intoxicated person, or pet, the person or pet should receive immediate medical attention to rule out the possibility of infection.

In culture

In Central America, representations of a Mayan bat divinity have been found on stone columns and clay containers about 2000 years old; this deity had the head of a bat and outstretched wings, and also appears in pictograms of this culture.

In many myths and legends, and in most parts of the world, bats have caused fear among humans throughout history. Because of the nocturnal habits of most of their species and the age-old misunderstanding of how they could "see" in the dark, they were and often are regarded as sinister denizens of the night. Furthermore, although only three species are actually blood-sucking, they are often associated with mythical vampires.

These superstitious fears are manifested almost everywhere in the world with few exceptions, such as China, where they are a symbol of happiness and profit; this fact is reflected in the Chinese word fu, which means both “happiness” and “bat”. These animals are often used, in groups of five (wu fu), as embroidery on clothing or as a round talisman. The five bats represent the five happinesses: health, wealth, long life, good luck and peace of mind; this ancient design is often depicted in red, the color of joy.

In Europe, bats have been viewed in a predominantly negative light since ancient times. Thus, in The Metamorphoses, Ovid explains that the daughters of the king of Boeotia were turned into bats as punishment, because they had stayed to work at the loom telling mythological stories, instead of participating in the festivities in Bacchus's honor The Bible also assigns them a negative condition, including them among the "unclean birds" (Lt 11.13, 19; Dt 14.11, 12, 18) and Isaiah considers the caves where they rest as appropriate places to throw idols (Is 2.19ff).

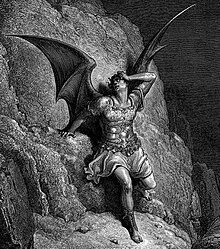

Demons and devilish creatures (including Satan himself) are often depicted in classical visual arts with bat wings, as opposed to angels.

In the famous engraving by Albrecht Dürer Melancholia I a creature similar to a bat appears holding a cartouche with the title of the engraving. During the Baroque they are one of the attributes of the Antichrist. The Spanish painter Francisco de Goya used them, along with owls, as a symbol of threat.

Bats are also associated with death and the soul; in some depictions of the 14th century century, the soul leaves the body after death rising in the form of a bat. European vampire legends may also have their origins in this association, dating back to times long before the discovery of true vampire bats in America. This myth of vampires has endured to this day in popular culture and is reflected above all in the imagination of writers and film directors; figures such as Count Dracula, who takes the form of a bat at night in search of victims, or in a multitude of films, such as The Vampire Ball, by Roman Polanski, which also use this myth.

In horror movies, bats frequently appear in caves and abandoned houses as fear-inspirers, and are even protagonists in films of the genre such as The Devil's Bat (1941), starring Bela Lugosi, or in Bats (1999), starring Lou Diamond Phillips and Dina Meyer.

The nocturnal life of these animals also inspired the creation of the comic book character and movie hero Batman, a superhero who disguises himself as a bat to go out to capture criminals at night and who chose this costume for fear that they infuse people.

Heraldry

In some areas of eastern Spain it is a heraldic symbol, and appears on the coats of arms of cities such as Valencia, Palma de Mallorca or Fraga. The heraldic use of the bat in Valencia, Catalonia and the Balearic Islands has its origins in the winged dragon (vibra or víbria), from the royal crest of King Pedro IV of Aragon.; This is the most widely accepted theory, although there is also a legend based on the Llibre dels feits that narrates that thanks to the intervention of a bat, King James I of Aragon won a crucial battle against the Saracens. during the Conquest of Valencia. Its use as a heraldic symbol is frequent in the territories of the former Crown of Aragon and little used elsewhere, although it can also be found on the coat of arms of the city of Albacete, in Spain, or in the city of Montchauvet, in France.

Additional bibliography

- Jones, K. E.; Bininda-Emonds, O. R. P.; Gittleman, J. L. (2005). "Bats clock,s, and rocks: diversification patterns in Chiroptera". Evolution (in English) 59 (10): 2243-2255. doi:10.1554/04-635.1.

- Kunz, T. H.; Fenton, M. B. (2006). Bat Ecology (in English). University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0226462072.

- Ramírez Pulido, J.; Arroyo Cabrales, J.; Castro Campillo, A. (2005). "Today state and nomenclatural relation of the land mammals of Mexico." Acta Zoológica Mexicana 21 (1): 21-82. ISSN 0065-1737.

- Toribio-Hernández, Edgar (2013). "Dinámica espacio-temporal de ensambles de murciélagos frugivoros in response to the availability of fruits in medium forests". Neotropical Chiroptera 19 (1): 1192-1197.

Contenido relacionado

Biodiversity

Quaternary structure of proteins

Human evolution