Chinese calligraphy

According to Chinese calligraphy, or shūfǎ (書法), Chinese characters can be drawn according to five historical styles. Normally all are done with brush and ink. These styles are intrinsically linked to the history of Chinese writing.

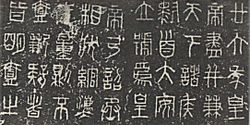

Stamp style

The oldest of the styles (with its heyday in the Qín dynasty, 221 BC-206 BC), known as seal script (篆書, zhuànshū), corresponds to an adaptation of the characters as they were engraved, not painted, on bronze or stone. The lines are fine and pointed at the ends, the curvature is not excluded, the shape of the characters is relatively free: this type of stroke does not follow the guidelines that are spoken of in other styles and that are essentially due to the brush. The characters are still quite close to the pictogram: their form cannot always be deduced from the modern form, since they are ancient forms that have undergone various alterations to reach their current form. Therefore, the stroke of the characters must be learned individually and their reading is not possible for the layman who only knows the modern characters.

Within the style of the seal, two types of characters can be distinguished: the great seal (大篆, dàzhuàn) and the small seal (小篆, xiǎozhuàn). The first is the oldest, most irregular, and the least cared for. It dates back to the IX century BCE. C. and derives directly from archaic characters, 甲骨文 jiǎgǔwén (under the Shāng dynasty) and 金文 jīnwén (under the Xīzhōu, or Western Zhōu), respectively " writing of oracles on bone" engraved on tortoise shells for fortune telling and "writing on bronze" on liturgical bronzes. These are the first authentic manifestations of Chinese writing. The great seal and archaic characters should not be thought of as the same thing: the great seal is the oldest type of script still in use, and not the oldest Chinese script.

The second, the small seal, is a standardization and refinement of the great seal dating from the Qín dynasty, modeled after Qín Shǐhuáng's prime minister Lǐ Sī (circa 200 BC). The small seal, superseded by simpler, more regular styles, originates from the usages of the Hàn (220-206 BCE) later becoming a purely solemn calligraphic style under the Táng (618-907). Normally drawn with a brush or engraved on the seals (origin of its current name). The great seal, for its part, is only studied by historians and scholars of writing.

Style of the scribes 隸書 lìshū

As the Chinese administration asserted itself through the power of writing, it seemed that the complex and irregular characters of the seal style were a brake on the speed of comprehension and learning of writing. It was for the officials, the scribes, for whom -according to tradition- Chéng Miǎo, prison director under the Qin dynasty (221 BC-206 BC), would have created a simpler plot style from the stamp style. This new style follows certain graphic rules (see on Wikipedia in French). Thus, Chéng Miǎo contributed to the development of learning and the improvement of the notation of administrative documents. That is why this style is attributed to officials (or scribes). This script becomes very common under the Hàn dynasty, in competition with the seal style, which it completely replaces (with the exception of calligraphy) between the 1st and 3rd centuries.

It is characterized by thick strokes with a hidden tip (the initial and final stroke of the brush is not visible). The strokes are square, flattened in the middle area, spaced out and tending to overflow on the sides. Along the s. II, under the Dōnghàn, or Eastern Hàn, the improvement of the brush led calligraphers to give more breadth to the strokes, mainly by adding undulations and stretching the horizontal lines.

This style is quickly replaced, from the III century, by the regular style. However, it continued to be used in calligraphy even to this day. It gives the composition a dignified, sententious and majestic air. It is therefore used, apart from calligraphy, mainly for slogans, illustrious citations and titles.

Regular style 楷書 kǎishū

Still under the Hàn, throughout the 3rd century AD, this style appears, considered as an improvement and rationalization of the style of the scribes. It is the standard script (正楷, zhèngkǎi), which had its heyday under the Táng (618-907 of our era) in which calligraphers definitively set the structure and technique of the line. The need for a simple script, as legible as possible, very regular, responded to the need for centralization of power. This writing, vector of the administration, has therefore participated, due to its stability, in the hegemony of imperial power, to such an extent that until the simplifications of 1958 and 1964 made in the People's Republic of China, it had not been retouched or modified.

Stylistically, it is characterized by the respect of the layout rules mentioned above: great stability (no character leaves the virtual square), the definitive abandonment of the direct curves and the sharp angles of the writing of the scribes by a smoother compromise, the ability to use no more than a defined number of fundamental strokes, horizontal strokes ascending slightly from left to right, and a modification of stroke initiation techniques.

There are two variants of the regular style: the large regular (大楷, dàkǎi) and the small regular (小楷, xiǎokǎi). The differences between the two come mainly from the brush technique: in the small regular one, the beginnings of the stroke are less complex, more fluid, and the general stroke is more agile, less rigid than in the large regular one, which is the most common of the two variants.

This is the regular style in which you learn to draw characters these days and in which you normally write when trying to write well. The regular style is very close to the printed characters, of which it has already been said that sometimes they present slight differences with the handwritten characters.

Standard style 行書 xíngshū

As its name indicates, this style, born again under the Hàn, towards the end of the Eastern Dynasty (25-220), is a double form: it is rapid (the characters "run") and usual ("current"). The style is born from a "deformation" by simplification of the regular stroke. That is why it is currently the most widely used for manuscripts of everyday life. However, it is not ignored by calligraphy, far from it, and it is not considered a bastard form of the regular one either: it has its own rules in calligraphy.

Its creator is believed to have been Liú Déshēng, of the Dōnghàn. The perfection of this style was achieved, however, by Wáng Xiànzhī (344-348) as well as Wáng Xīzhī (321-379), his father, one of the most famous Chinese calligraphers, both under the Dōngjìn dynasty, or Dōngjìn (317- 420 of our era).

Traced with the tip of a brush or pen, it remains legible, quick to write, and easily decipherable. It does not require its own learning, separate from the regular one, since it is an almost cursive spelling, the simplifications of the characters are logical: they are stylizations of the basic units born naturally from the brush or the pen when the tip does not leave the paper for a new stroke, which are joined more often than in the regular style. In addition, the strokes are simpler and more direct (the tip of the brush does not return back, a characteristic movement of the regular style).

Grass style 草書 cǎoshū

The last of the calligraphic styles, also called cursive or crazy writing is undoubtedly the most surprising. Its name can be understood in several ways: either that it is a waved script like grass (it is one of the senses of the character 草 cǎo) in the wind, or that it is intended for ephemeral uses, as a eraser (another of the possible senses of 草), like straw. Far from being a stenographic form, born from the previous one, it is a type of writing entirely apart. The lines of the characters -which appear strongly deformed, appear to be shapes without apparent constraints, often linked together and moving away from the virtual square- rest on shorthand forms taken from previous styles. Reading and writing in this style are reserved for calligraphers and scholarly specialists.

The history of this style, which has undergone frequent modifications, is complex. Two main historical italics are distinguished, the "seals italics" (章草 zhāngcǎo) and the "new italic" (今草 jīncǎo). The first, first attested in the Warring States, 戰國 Zhànguó 475 BC. c.-221 a. C., and which was perfected under the Hàn, derives from the style of the scribes and the seal. The second, also created under the Hàn in the 2nd century AD, is a modification of the zhāngcǎo. If the characters of the first italics are separated from each other and are relatively regular, those of the second take on more independence, reaching the total elimination of the limits between strokes and characters. Wáng Xiànzhī and Wáng Xīzhī of the Dōngjìn (317-420), are considered the masters in the matter.

The style is characterized mainly by a highly coded stroke of the characters, which are abbreviated and reduced to their fundamental form and are no longer recognizable to the lay eye. The reductions come either from a natural simplification of the stroke, with which the brush hardly lifts off the paper, or from conventional stenographic spellings, sometimes very old, which could have given rise to some of the simplified characters of the People's Republic of China. The calligrapher who works in this grass style however does not necessarily draw the characters more quickly than in the other styles: the speed is suggested and described but not sought by itself. This style, in fact, is not currently used for drafts: it requires such a knowledge of Chinese writing and its history and such a mastery of technique that it has been reserved mainly for art. In fact, though italic, the grass style is most often carefully drawn.

One can easily talk about abstract art and the idealization of writing, since it is only sketched, the movements being written more than the strokes.

One can easily talk about abstract art and the idealization of writing, since it is only sketched, the movements being written more than the strokes.

Style dictionaries

To help calligraphers and amateurs alike, there are stylistic dictionaries, which give for each of the Chinese characters mentioned the five spellings (actually six counting the printed variety, which may differ slightly from the regular spelling)..

Contenido relacionado

113

56

Camille Pissarro