Chinese art

Since the origins of Chinese history, objects were created in bronze, jade and bone that reflected the spirit and effect sought in shamanistic rituals.

These bronze and jade forms show for the first time one of the essential principles of Chinese art: the synthesis between the artistic creative spirit and the social and hierarchical function to which they were destined from their conception. The first of them was shown in the exquisiteness of the shapes, in the origin of the decorative themes taking the forces of nature and their action on the human spirit as a paradigm, and in the great technical knowledge of the materials that has characterized all the artistic forms.

As a complement, both the diversification of the forms and the iconography with which they were adorned corresponded to the principles of social hierarchy and ritual use that characterized the beginnings of Chinese civilization with the Shang Dynasty and the Zhou Dynasty. In this last dynasty, the schools of philosophy arose that, delving into the relationship of the individual with his environment and his social consideration, would establish the theoretical foundations on which centuries later the Chinese theory of art would develop.

We are referring fundamentally to Taoism and Confucianism, without thereby affirming that there is a clear division between what some consider Taoist art as a disintegrated manifestation of a supposed Confucian art.

Lines and brushstrokes in Chinese art

It is true that poetry, painting and calligraphy all represent through the brush, the very essence of Taoist artistic thought, but it must not be forgotten that even these sublime arts had their social function, their hierarchy and consequently participated in the confucian thought.

These were art with capital letters, reserved for an intellectual class trained in the classics, and tradition, where the artist and the work of art were recognized and valued as a unit and not as a social product. From the first script treated artistically and converted into the art of calligraphy by Wang Xizhi in the 4th century AD. C. until the last heterodox of the Qing Dynasty, the painters Zhuda and Shitao, calligraphy, painting and poetry have been united in the same technical and aesthetic principles.

The basic instruments —ink, paper, brush and inkwell—, the classical formation, and the search for rhythm, spontaneity and expressiveness based on the line, the brushstroke and the void have been the common elements from which have developed diachronically over the centuries.

The word, the character is considered as an image, as the abstraction of an idea and concept, and the pictorial image in which both a character and a landscape are recognized is read as a word, thus merging thought artistic in poetry-calligraphy-painting.

A taste for materials in art

Some of these materials developed in a way that was almost unique in a given historical context, while others were adopted into new uses and forms. Thus we observe that bronze and jade are characteristic of the Shang and Zhou dynasties, always linked to ritual and social representation.

Lacquer and silk coincide in being associated with the historical moment of political and cultural expansion of the Chinese empire during the Han dynasty (206 BC-220 AD), being also the first materials on which he designs thinking only of the beauty of the object and not of its ritual use.

Since the reign of Qin Shi Huang, ceramics, whose first forms appeared in the Neolithic, serving in many cases as a reference to forms in bronze, acquired greater value as they reproduced the great imperial army with which they the emperor wanted to protect his mausoleum underground.

From then on, ceramics (clay, terracotta, stoneware and porcelain) became, thanks to the labor organization capacity of pottery centers, technical innovations and the skill of artisans in the most versatile and polysemantic material of all.

From the simplicity of fired and painted clay, the Chinese potter has been able, through the application of glazes and decorative techniques and the control of firing, an immense formal and typological variety, capable of satisfying all tastes and needs.

The scarcity of other materials (bronze, jade), led to an attempt to find the chromatic and plastic effects of other materials through varnishes. Thus, the iron oxide varnish treated in a reducing atmosphere produced a chromatic range from olive-green to lavender blue with which it was intended to imitate the appearance of jade. This decorative technique known in China since the Han Dynasty lasted until the 20th century, with the green color of these pieces being renamed celadon by Europeans.

Ceramic funerary pieces found their best expression in the Tang Dynasty with the application, by immersion and dripping, of three colors (or sancai).

In the Song Dynasty, the uses and forms of pottery were totally transformed. The knowledge of kaolin since the 10th century —a necessary ingredient to obtain porcelain— together with the economic development of this dynasty and the search for greater exquisiteness in the design of everyday objects by the literate class, allowed the appearance of new ceramic types. This is how the products destined for imperial use were differentiated, compared to those requested by lawyers, merchants and monastic communities.

The turn of the 13th century was reflected in the artistic field in its industrialization and its distribution abroad. The blue and white ceramic type is the most characteristic of this transformation, being synonymous with the new iconographic repertoire and the gradual change in its distribution and spatial conception that would affect all the materials.

The last dynasty showed the world a taste for ornamentation, technical exuberance and formal flaunting, in a variety of shapes and materials, reflecting the new taste and aesthetics of the Manchu Dynasty.

Art for representation and the community

Along with the aesthetic delicacy of the indicated materials, designed for private enjoyment and in some cases also as a symbol of social position, there were other ways of understanding art.

Stone sculpture and wooden architecture were the channels through which society manifested itself as a deeply hierarchical community.

Stone sculpture began as a majestic and representative decoration of the funerary pathways of imperial tombs in the Han Dynasty. Large real and mythological animals, representations of social classes —learned, military, foreigners, etc.— were the themes chosen to dignify power.

That is why it is an anonymous art, the creation of collective workshops, where the stone was carved monolithically as a material and concept. Of all this are the sculptures that flank the path of the spirits of the Han and Tang dynasties and especially the Ming tombs, as well as the representative sculpture of the imperial palaces.

But the sculpture also had religious purposes linked to the spread of Buddhism in China. The Yungang, Longmen and Dunhuang Grottoes display the stone, brick and stucco work that shaped the Buddhist pantheon. In them, foreign influence and its transformation or adaptation to Chinese taste and aesthetics can be appreciated, as one of the greatest contributions of the exchanges produced on the Silk Road.

The palatial, funerary, religious and civil architecture started from simple construction systems and spatial distribution, mainly echoing its character of representativeness.

For this reason, it was not considered a creative art either, but as a work of craftsmen, especially carpenters and decorators, where innovations in design or construction technique had no place.

Among the most significant examples of Chinese architecture are the palaces —Forbidden City, Veracruz Palace, Chengde—, and temples —Temple of Heaven, Wild Goose Pagoda—, in which the imbrication of all artistic materials and their double artistic and representative function.

Chinese Architecture

Chinese architecture is characterized by distributing space into rectangular units that come together to form a whole. The Chinese style combines rectangles of different sizes and in different positions according to the importance of the organization of the whole, hence its pyramidal constructions: it uses feng shui. The different levels and elements are clearly distinguished. The result is an impressive external appearance, but at the same time dynamic and mysterious.

In traditional Chinese architecture, the distribution of spatial units is governed by the principles of balance and symmetry. The axis constitutes the main structure. The secondary structures are located on both sides of the axis, forming the central courtyard and the main rooms. Both houses and official buildings, temples and palaces conform to this fundamental principle. The distribution of the interior space reflects the ethical and social values of the Chinese.

In traditional homes, for example, rooms are assigned according to each person's position in the family hierarchy. The head of the family occupies the main room, the older members of the latter's family live in the back and the younger ones in the left and right wings; the older ones on the left and the younger ones on the right.

Chinese architecture is also characterized by the use of a structure of wooden beams and pillars and an adobe wall that surrounds three of the sides of the building. The main door and windows are located at the front. The Chinese have been using wood as one of their main building materials for thousands of years. Wood represents life and this is the main idea that Chinese culture, in its multiple manifestations, tries to communicate. This feature has survived to this day.

History

Chinese art has had a more uniform evolution than Western art, with a common cultural and aesthetic background to the successive artistic stages, marked by their reigning dynasties. Like most oriental art, it has an important religious charge (mainly Taoism, Confucianism and Buddhism) and communion with nature. Unlike in the West, the Chinese valued calligraphy, ceramics, silk or porcelain equally as architecture, painting or sculpture, while art is fully integrated into their philosophy and culture.

- Dinastía Shang (1600-1046 B.C.): it was highlighted by its objects and bronze sculptures, especially vessels decorated in relief and masks and anthropomorphic statues, such as those found in the Chengdu area, in the Upper Yangtse, of about 1200 B.C. Archaeological remains of several cities have been found in the Henan area, walled and with a rectangular reticle. These settlements have also been found tombs with rich weapons, jewellery and various bronze, jade, ivory and other materials.

- Dinastía Zhou (1045-256 a. C.): evolving from Shang art, the Zhou created a decorative and ornamental style, of stylized and dynamic figures, continuing the work in copper. A nomadic invasion in 771 a. C. fragmented the empire in small kingdoms, during which agriculture and metallurgy flourished, appearing various local artistic styles in the so-called Period of the Combating Kingdoms. Taoism and confucianism appeared, which would greatly influence art. He highlighted the work in jade, decorated in relief, and the lacquer appeared.

- Qin Dynasty (221-206 BC): unified China under the reign of Qin Shi Huang, the Great Wall was built to avoid external invasions, with 2400 kilometers long and an average of 9 meters high, with guard towers of 12 meters high. It highlights the great archaeological finding of the terracotta Army of Xi'an (210 B.C.), located inside the Mausoleum of Qin Shi Huang. It is composed of hundreds of terracotta statues of natural-made warriors, including several horses and chariots, with great naturalism and precision in physiognomy and details.

- Han Dynasty (206 B.C.-220 AD): the time of peace and prosperity, Buddhism was introduced, which had a slow but progressive implantation. He stood by his funeral chapels, with statues of lions, tigers and horses. The painting focused on themes of the imperial court, nobles and officials, with a confusing sense of solemnity and moral virtue. They are also to mark the reliefs in sanctuaries and chambers of offerings, usually dedicated to confucian motives, in a linear style of great simplicity.

- Period of the Six Dynasties (220-618): Buddhism was more widely spread, building large shrines with colossal statues of Buddha (Yungang, Longmen). Alongside this new religion, and thanks to the Silk Road, various influences were received from West Asia. In painting the six principles were formulated, enunciated by Xie He at the beginning of the sixth century, and the artistic calligraphy began with the legendary figure of Wang Xianzhi.

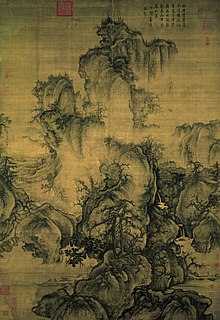

- Tang Dynasty (618-907): this was one of the most flourishing periods of Chinese art, highlighting its sculpture and its famous ceramic figures. The most represented figure remained Buddha, as well as the bodhisattvas (Buddhist mystics), highlighting the polychrome wood statue Guan Yin (o) Bodhisattva de la Misericordia2.41 meters high. In architecture the main typology was the pagoda (Hua-yen, Hsiangchi). In painting the landscape appeared, initially a genre of elitist sign, destined to small cultural circles. Unfortunately, the Tang landscapes have not arrived until today, and are only known for copies, as Buddhist temple on the hills after the rainLi Cheng (X century).

- Song Dynasty (960-1279): a period of great flourishing of the arts, a high level of culture was reached that would be remembered with great admiration in later stages. The engraving on wood appeared, impregnated with ink on silk or paper. In architecture continued the construction of pagodas, such as the hexagonal pagoda of Kuo-Hsiang-Su (960), or the payment of wood of Chang-Tiu-Fu. In ceramics two typologies stand out: the white enamel ceramic of Ting-tcheu, and the pink or blue enamel ceramic of Kin-tcheu. In painting the landscape continued, with two styles: the north, of precise drawing and sharp colors, with figures of monks or philosophers, flowers and insects; and the south, of quick brushstrokes, light and diluted colors, with special representation of cloudy landscapes.

- Yuan Dynasty (1280-1368): Mongolian dynasty (its first emperor was Kublai, the grandson of Gengis Kan), China opened more towards the West, as is evident in Marco Polo's famous journey. In architecture stands out the White Pagoda of Beijing. Decorative arts were especially developed: carpets were manufactured, ceramics were produced with new shapes and colors, and works of metalwork of great wealth were produced. In painting religious themes, especially Taoists and Buddhists, were proliferated, highlighting the mural paintings of the Yonglegong temple (Shanxi), and artists such as Huang Gongwang, Wang Meng and Ni Zan.

- Ming Dynasty (1368-1644): it was the restoration of an indigenous dynasty after the Mongolian period, returning to the ancient Chinese traditions. The third emperor of the dynasty, Yongle, moved the capital of Nanking to Beijing (1417), building an Imperial Palace (the Forbidden City), with three large courtyards surrounded by a wall of 24 kilometers, and a wide complex of buildings where the Hall of the Supreme Harmony (with the imperial throne) and the Temple of Heaven stand out. The painting of this era was traditional, of a naturalistic sign and a certain opulence, as in the work of Lü Ji, Shen Zhou, Wen Zhengming, etc. He also highlighted the porcelain, very light and bright tones, usually in white and blue, and developed the decoration of bronze vessels in enamel cloisonné, technique that had come to China from Byzantium and Central Asia during the Yuan dynasty. The cloisonné He experienced an interesting process of artistic hybridization in China, particularly in the pieces promoted by Chinese missionaries and Christian communities.

- Qing Dynasty (1644-1911): Manchu-origin dynasty, in art meant the continuity of traditional forms. The painting was quite eclectic, dedicated to floral themes (Yun Shouping), religious (Wu Li), landscapes (Gai Qi), etc. In architecture, the construction—and, in some cases, restoration—of the imperial enclosure, with the same stylistic seal, was continued, while new aristocratic temples and villas were built, highlighting the richness of materials (marble balustrades, ceramic on the roofs, etc.). The tradition also continued in the applied arts, especially ebanistry, porcelain, silk fabrics, lacquers, enamel, jade, etc. It should be mentioned that Chinese manufactures influenced the decoration of the European Rocococo (the so-called Chineseiseries).

- Contemporary art: the end of the imperial era meant the modernization of China, which opened more to Western influence. The triumph of the communist revolution imposed socialist realism as official art, although recently the new aperturist policy has favored the arrival of the latest artistic tendencies, linked to new technologies. In 1989, the exhibition was greatly resonated China/Vanguard, at the Chinese National Gallery of Beijing, which showed the latest creations of the moment, including both pictorial work and photographs, installations and performances. Unfortunately, the events of Tiananmén provoked a new setback, until a new opening in 1992. The most relevant contemporary Chinese artists are: Qi Baishi, Wu Guanzhong, Pan Yuliang, Zao Wou-Ki and Wang Guangyi.

Contenido relacionado

David (Michelangelo)

Palace of the Counts of Buenavista

Pedro de Gamboa