Charles Linnaeus

Carlos Linnaeus (Swedish: Carl Nilsson Linnæus, Latinized as Carolus Linnæus) (Råshult, 23 May 1707- Uppsala, January 10, 1778), also known after his ennoblement as Carl von Linné, was a Swedish scientist, naturalist, botanist, and zoologist.

Considered the creator of the classification of living beings or taxonomy, Linnaeus developed a system of binomial nomenclature (1735) that would become classic, based on the use of a first term, with its initial letter written in capital letter, indicative of the genus and a second part, corresponding to the specific name of the described species, written in lower case. On the other hand, he grouped genera into families, families into classes, classes into types (row) and types into kingdoms. He is considered one of the fathers of ecology.

Linnaeus was born in the rural region of Råshult, in southern Sweden. His father, Nils, was the first of his line to adopt a permanent surname; previously, ancestors used the patronymic-based naming system, as was traditional in Scandinavian countries. Inspired by a linden tree on the family land, Nils chose the name Linnaeus, as a Latinized form of lind, Swedish for “linden”. Linnaeus did much of his higher education at the University of Uppsala and, around 1730, he began to give lectures on botany. He lived abroad between 1735-1738, where he studied and published a first edition of his Systema naturæ in the Netherlands. Back in Sweden he became a professor of botany at Uppsala. During the 1740s, 1750s, and 1760s, he made several expeditions across Sweden to collect and classify plants, animals, and minerals, and published several volumes on the subject. At the time of his death, he was recognized as one of the foremost scientists in all of Europe.

The philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau sent him the message: "Tell him I don't know a greater man on earth." The German writer Goethe wrote: "With the exception of Shakespeare and Spinoza, I know no one, among those who are no longer living, may it have influenced me more strongly." The Swedish author Strindberg wrote: "Linnaeus was actually a poet who became a naturalist." Among other compliments, Linnaeus was called "Princeps Botanicorum » («Prince of Botanists»), «The Pliny of the North» and «The Second Adam». He is also considered a national hero of Sweden.

His remains, buried in Uppsala, are considered the nomenclatural (symbolic) type for the species Homo sapiens.

Biography

Early Years

Childhood

Carlos Nilsson Linnaeus was born in Råshult, Småland, Sweden, on May 23, 1707. He was the eldest son of Nils Ingemarsson Linnaeus (1674-1748) and Christina Brodersonia (1688-1733). Nils's ancestors had been peasants or priests for many generations. His father, Nils, was a Lutheran pastor from the small town of Stenbrohult, in Småland, and an amateur botanist. His mother, Christina, was the daughter of Stenbrohult's rector, Samuel Brodersonius. After Carlos, three daughters were born and another son, Samuel, who would eventually succeed his father as rector at Stenbrohult and write a manual on beekeeping. A year after the birth of Carlos Linnaeus, his grandfather, Samuel Brodersonius, died and his father, Nils, became the chancellor of Stenbrohult. Thus, Linnaeus and his parents moved to the rectory, leaving the pastor's house where they had lived.

Even in his early years, Linnaeus seemed to show an attraction to plants and flowers in particular. When he was worried or angry, they would give him a flower, and he would immediately calm down. Nils spent a lot of time in his garden and often showed Linnaeus flowers, teaching him their names.Soon, Linnaeus had his own plot of land in his father's garden, where he could grow plants.

Basic education

His father began to teach him Latin, religion, and geography at an early age, but when Linnaeus was seven years old, he thought it better for him to have an educator. His parents chose Johan Telander, the son of a local “husbonde” (a minor landowner). Telander was not liked by Linnaeus, who would later write in his autobiography that Telander "was better at extinguishing a child's talent than developing it."Two years after he had started teaching, he was sent to the Elementary Institute in Växjö. Linnaeus rarely studied; instead, he often went to the fields to look for plants. However, he made it to the last year of elementary school when he was fifteen, in 1722. This course was taught by primary school principal Daniel Lannerus, who was interested in botany. Lannerus noticed Linnaeus's interest in her and gave her classes in his garden. He also introduced her to Johan Rothman, who was the state doctor for Småland and a teacher at the Växjö Gymnasium. Rothman, who for a doctor at the time was also a botanist, deepened Linnaeus's interest in botany and helped him develop an interest in medicine.

Having spent the last seven years in a high school, Linnaeus entered the Växjö Gymnasium in 1724. Theology, Greek, Hebrew, and mathematics were studied there, a curriculum designed for someone aspiring to be a religious minister. In the last year at the gymnasium, Nils, Carlos Linnaeus's father, visited his teachers to ask how his studies were progressing; to his surprise, most of them told him that "Linnaeus would never be a good student." However, Rothman was convinced and suggested that Linnaeus might have a future in medicine. Rothman also offered to house Linnaeus in Växjö and teach him physiology and botany. Nils accepted this offer.

University

Lund

Rothman showed Linnaeus that botany was a serious subject and not just entertainment. He taught her to classify plants according to the Tournefort system. Linnaeus was also educated on the sexuality of plants according to Sébastien Vaillant.In 1727, at the age of 21, he enrolled at the University of Lund, in Scania.Linnaeus was tutored and housed by the local doctor Kilian Stobaeus. There he could use the doctor's library, which had many books on botany, and had free access to lectures given by Stobaeus himself.In his spare time, he explored the flora of Scania together with the students who shared the same interests.

Uppsala

In August 1728, Linnaeus decided to go to Uppsala University on the advice of Rothman, who believed that he would be the best choice whether he wanted to study medicine or botany. Rothman based this recommendation on the two professors who taught at the Uppsala medical college: Olof Rudbeck the Younger and Lars Roberg. Both Rudbeck and Roberg had undoubtedly been good teachers, but by then they were older and had little interest in teaching. Rudbeck, for example, stopped lecturing in public, and allowed other less-trained people to do it for him; thus, lectures on botany, zoology, pharmacology, and anatomy were not given at their best level. In Uppsala, Linnaeus found a new benefactor, Olof Celsius, a professor of theology and amateur botanist. Olof received Linnaeus at his home and offered him gave entry into his library, which was one of the most comprehensive botanical libraries in Sweden.

In 1729, Linnaeus wrote the thesis Praeludia sponsaliorum plantarum on the sexuality of plants. This caught the attention of Olof Rudbeck, who, in May 1730, selected Linnaeus to start teaching at the university, even though he was only a sophomore. The lectures were very popular and Linnaeus could find himself speaking to an audience of 300 people. In June, he moved from the Celsius home to the Rudbeck home to tutor and teach the three youngest of his 24 children. His friendship with Celsius did not diminish and they continued to go on botanical expeditions together.During that winter, Linnaeus began to doubt Tournefort's classification system and decided to create his own. His plan was to divide the plants by the number of stamens and pistils; he began to write a few annotations that would later become books, such as Genera plantarum and Critica botanica . He also produced the book Adonis Uplandicus , concerning the plants grown in his garden.

Rudbeck's former assistant, Nils Rosen, returned to the University in March 1731 with a degree in Medicine. Rosen was beginning to teach anatomy and was trying to take over Linnaeus's botany lectures; however, Rudbeck stopped him. Until December, Rosen tutored Linnaeus in Medicine. In December, Linnaeus, because of a "disagreement" with Rudbeck's wife, had to leave his house, although his relationship with Rudbeck seems to have remained unscathed. That Christmas Linnaeus returned home to Stenbrohult to visit his parents for the first time in about three years. His mother's feelings for him had cooled since she had decided not to become a pastor, but when she saw that she was teaching at the University, she was pleased.

University

Lund

Rothman showed Linnaeus that botany was a serious subject and not just entertainment. He taught her to classify plants according to the Tournefort system. Linnaeus was also educated on the sexuality of plants according to Sébastien Vaillant.In 1727, at the age of 21, he enrolled at the University of Lund, in Scania.Linnaeus was tutored and housed by the local doctor Kilian Stobaeus. There he could use the doctor's library, which had many books on botany, and had free access to lectures given by Stobaeus himself.In his spare time, he explored the flora of Scania together with the students who shared the same interests.

Uppsala

In August 1728, Linnaeus decided to go to Uppsala University on the advice of Rothman, who believed that he would be the best choice whether he wanted to study medicine or botany. Rothman based this recommendation on the two professors who taught at the Uppsala medical college: Olof Rudbeck the Younger and Lars Roberg. Both Rudbeck and Roberg had undoubtedly been good teachers, but by then they were older and had little interest in teaching. Rudbeck, for example, stopped lecturing in public, and allowed other less-trained people to do it for him; thus, lectures on botany, zoology, pharmacology, and anatomy were not given at their best level. In Uppsala, Linnaeus found a new benefactor, Olof Celsius, a professor of theology and amateur botanist. Olof received Linnaeus at his home and offered him gave entry into his library, which was one of the most comprehensive botanical libraries in Sweden.

In 1729, Linnaeus wrote the thesis Praeludia sponsaliorum plantarum on the sexuality of plants. This caught the attention of Olof Rudbeck, who, in May 1730, selected Linnaeus to start teaching at the university, even though he was only a sophomore. The lectures were very popular and Linnaeus could find himself speaking to an audience of 300 people. In June, he moved from the Celsius home to the Rudbeck home to tutor and teach the three youngest of his 24 children. His friendship with Celsius did not diminish and they continued to go on botanical expeditions together.During that winter, Linnaeus began to doubt Tournefort's classification system and decided to create his own. His plan was to divide the plants by the number of stamens and pistils; he began to write a few annotations that would later become books, such as Genera plantarum and Critica botanica . He also produced the book Adonis Uplandicus , concerning the plants grown in his garden.

Rudbeck's former assistant, Nils Rosen, returned to the University in March 1731 with a degree in Medicine. Rosen was beginning to teach anatomy and was trying to take over Linnaeus's botany lectures; however, Rudbeck stopped him. Until December, Rosen tutored Linnaeus in Medicine. In December, Linnaeus, because of a "disagreement" with Rudbeck's wife, had to leave his house, although his relationship with Rudbeck seems to have remained unscathed. That Christmas Linnaeus returned home to Stenbrohult to visit his parents for the first time in about three years. His mother's feelings for him had cooled since she had decided not to become a pastor, but when she saw that she was teaching at the University, she was pleased.

Expedition to Lapland

When Linnaeus visited his parents, he explained his plan to go to Lapland, a trip Rudbeck had once made, but the results had been destroyed in a fire in 1702. Linnaeus's hope was to find new plants, animals and possibly valuable minerals. He was also curious about the customs of the native Sami, nomadic reindeer herders who roamed the great tundras of Scandinavia. In April 1732, Linnaeus was awarded a grant from the Uppsala Royal Society of Sciences to finance the expedition.

Linnaeus began his journey on May 22. He did it on foot and on horseback, taking with him his diary, botanical and ornithological manuscripts, and leaves for herbifying plants. It took him eleven days to reach his first objective, Umeå, dismounting on the way to examine a flower or a rock. He was especially interested in mosses and lichens, an important food item for reindeer, a common animal in Lapland., reached Gävle, where he found large quantities of Campanula serpyllifolia, a creeping perennial plant that would become a favorite of Linnaeus, later renamed Linnaea borealis.

After being in Gävle, Linnaeus headed towards Lycksele, a town further from the coast than he had been before, examining ducks on the way. After five days, he arrived in the city, where he stayed with the pastor and his wife. In early June, he returned to Umeå, after spending a few days in Lycksele, where he learned more about Sami customs. From Umeå, he moved north into the Scandinavian mountains, passing through Old Luleå, where he received a Lappish woman's hat. He crossed the Norwegian border at Sørfold, some 300 km from Old Luleå. Later, he went to Kalix and, in mid-September, he began his journey back to Uppsala via Finland and took the ship to Turku. He arrived on October 10, having made a total journey of six months and about 2,000 km, during which he collected and observed an innumerable number of plants, birds and rocks. Although Lapland was a region without much biodiversity, Linnaeus found and described a hundred previously unknown plants. His discoveries would later be the basis of the book Flora lapponica .In 1734, Linnaeus traveled to Dalarna at the head of a small group of students. The trip was funded by the Governor of Dalarna to catalog known natural resources and discover new ones, but also to have the results collected in Røros along with Norwegian mining activities.

European excursions

PhD

Back in Uppsala, Linnaeus's relations with Nils Rosen worsened and he kindly accepted an invitation from student Claes Sohlberg to spend the Christmas holidays with his family in Falun. Sohlberg's father was a mining inspector and took Linnaeus to visit the mines near Falun Sohlberg's father suggested that Linnaeus take his son to the Netherlands and continue teaching her there for an annual salary. At the time, the Netherlands was one of the most revered places to study natural history and a common place for Swedes to do their doctorates. Linnaeus, who was interested in both, accepted.

In April 1735, Linnaeus and Sohlberg left for the Netherlands. Linnaeus obtained the degree of Doctor of Medicine at the University of Harderwijk. On the way, he stopped in Hamburg, where the two had a meeting with the mayor, who proudly showed them a wonder of nature that he possessed: the embalmed remains of a Lernaean hydra with seven heads. Linnaeus immediately saw that it was false: the jaws and feet of weasels and the skin of snakes had been glued on. The hydra's provenance led Linnaeus to believe that it had been made by monks to represent the Beast of Revelation. Although this may have worried the mayor, Linnaeus went public with his observations, and the mayor's dream of selling the hydra for a huge sum was completely ruined. Fearing his wrath, Linnaeus and Sohlberg quickly left Hamburg.

When Linnaeus arrived in Harderwijk, he immediately began his undergraduate studies. First, he presented a thesis on the cause of malaria that he had written in Sweden. He then defended his thesis in a public debate. The next step was an oral examination and diagnosing a patient. After less than two weeks, he graduated and became a doctor at age 28. Over the summer, Linnaeus met a friend from Uppsala, Peter Artedi. Before leaving Uppsala, Artedi and Linnaeus had decided that if one of them were to die, the survivor should finish the other's work. Ten weeks later, Artedi drowned in one of the Amsterdam canals, and his unfinished manuscript on the classification of fish was left to Linnaeus for completion.

Publication of Systema naturæ

One of the first scientists Linnaeus met in the Netherlands was Jan Frederik Gronovius, to whom he showed one of the manuscripts he had brought with him from Sweden. The manuscript described a new system of classifying plants. When Gronovius saw it, he was very impressed, offering to help pay for the printing of him. With an additional monetary contribution from Scottish doctor Isaac Lawson, the manuscript was published under the name Systema naturæ. Linnaeus became acquainted with one of the most respected physicians and botanists in the Netherlands, Herman Boerhaave, who tried to convince him to make a career in his country. Boerhaave offered him a trip to South Africa and America, but Linnaeus excused himself, stating that he couldn't stand the heat. Boerhaave suggested that he visit the botanist Johannes Burman, which Linnaeus did. After the visit of Carlos Linnaeus, Burman was impressed by the knowledge of his guest and decided that Linnaeus would stay with him during the winter. During his stay, Linnaeus helped Burman with his Thesaurus Zeylanicus . Burman also helped Linnaeus with the books he was working on: Botanica Fundamentals and Bibliotheca Botanica .

Its full title is Systema naturæ per regna tria naturæ, secundum classes, ordines, generates, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis, translated as: «Natural system, in three kingdoms of nature, according to classes, orders, genera and species, with characteristics, differences, synonyms, places». The tenth edition of this book is considered the starting point of zoological nomenclature.

George Clifford

In August, during his stay with Burman, Linnaeus met George Clifford III, a director of the Dutch East India Company and owner of a botanical garden near Hartecamp in Heemstede. Clifford was very impressed with Linnaeus's ability to classify plants and invited him to become his doctor and gardener. Linnaeus had already agreed to stay with Burman for the winter and could not immediately accept the invitation. However, Clifford offered to make it up to Burman by offering him a copy of Sir Hans Sloane's Natural History of Jamaica, a rare book, if Linnaeus would agree to keep it. Burman agreed. September 1735, Linnaeus became Hartecamp's personal botanist and medical conservator, free to buy any book or plant he wanted.

In July 1736, Linnaeus traveled to England, at Clifford's expense. He went to London to visit Sir Hans Sloane, a collector of Natural History, and to look at his collection. Another reason for his trip to England was visit Chelsea Physic Garden and its curator, Philip Miller. He introduced Miller to his new plant classification system which was described in Systema naturæ . Miller was impressed and from then on began arranging the botanical garden according to Linnaeus's system. Linnaeus also went to Oxford University to visit the botanist Johann Jacob Dillenius. He failed to get Dillenius to publicly accept his new classification system. He then returned to Hartecamp, taking many rare plant specimens with him. The following year, he published Genera Plantarum, in which he briefly described 935 genera of plants and was later supplemented by Corollarium Generum. Plantarum, with sixty more genera. His work at Hartecamp led to the publication of a new book, Hortus Cliffortianus, a catalog of the herbal holdings and Hartecamp's Botanists, written in nine months, completed in July 1737 but not published until 1738.

Linnaeus stayed with Clifford at Hartecamp until October 18, 1737, when he left for Sweden. Illnesses and the kindness of his Dutch friends made him stay a few more months in Holland. In May 1738, he went to Sweden again. On the way he stopped in Paris for about a month, visiting botanists like Antoine de Jussieu. After his return, Linnaeus never left Sweden again.

Return to Sweden

When Linnaeus returned to Sweden on June 28, 1738, he went to Falun, where he was hired by Sara Elisabeth Moraea. Three months later, he moved to Stockholm to find work as a doctor so he could support his family. Once again, Linnaeus contacted Count Carl Gustav Tessin, who helped him get a job as a doctor at the Admiralty. During this stay in Stockholm, Linnaeus helped found the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, becoming the academy's first praeses (president) by lot.

When his finances had improved and he was enough to have a family, he got permission to marry his fiancée, Sara Elisabeth Moræa. The wedding took place on June 26, 1739. Seven months later, Sara gave birth to her first child, Carl. Two years later, a daughter, Elisabeth Christina, was born, and the following year, Sara had Sara Magdalena, who died 15 days later. Sara and Linnaeus would later have four other children: Lovisa, Sara Christina, Johannes and Sophia. Johannes died before he was three years old. In May 1741, Linnaeus was appointed Professor of Medicine at the University of Uppsala, initially with responsibility for medical-related topics. He soon switched positions with another Professor of Medicine, Nils Rosen, and thus got responsibility for the botanical garden (which he would painstakingly rebuild and expand), botany, and natural history. In October of that same year, his wife and nine-year-old son moved to live with him in Uppsala.

Sweden Further Exploration

Oland and Gotland

Ten days after being appointed professor, he set out on an expedition to the island provinces of Öland and Gotland, with six university students, to search for plants useful in medicine. They first traveled to Öland, where they stayed until June 21, when they embarked for Visby. Linnaeus and the students stayed on Gotland for about a month, then returned to Uppsala. During this expedition, they discovered about 100 plant species not yet recorded. The expedition's observations were later published in Öländska och Gothländska Reza, written in Swedish. As in the case of Flora lapponica, the book contains both zoological and botanical observations, as well as observations on culture on Öland and Gotland. During the summer of 1745, Linnaeus published two more books: Swedish Flora and Swedish Fauna. Flora Suecica was a strictly botanical book, while Fauna Suecica was zoological.Anders Celsius had created the temperature scale named after him in 1742; the Celsius scale worked inversely to how we know it today; the boiling point of water was 0 °C and the melting point 100 °C. In 1745 Linnaeus inverted the scale, giving it its current format.

Vastergotland

During the summer of 1746, Linnaeus was again commissioned by the government to go on an expedition, this time in the Swedish province of Västergötland. He left Uppsala on June 12 and returned on August 11. On the expedition, his main companion was Erik Gustaf Lidbeck, a student who had accompanied him on his previous trip. Linnaeus described the discoveries of the expedition in the book Wästgöta-Reza, published the following year. After returning from his trip, the Government decided that Linnaeus should accept another expedition in the southern province of Scania. This trip was postponed due to the large amount of work Linnaeus had to do. In 1747, he was awarded the title of archiatre, or chief physician to the Swedish King Adolf Frederick, a highly regarded position. The same year he was elected a member of the Berlin Academy of Sciences.

Scan

In the spring of 1749, Linnaeus was finally able to travel to Scania, on behalf of the government, accompanied by his student Olof Söderberg. On the way to Scania, he paid his last visit to his brothers and sisters at Stenbrohult since his father's death the year before. The expedition was similar to previous voyages in most respects, but this time he was also tasked with finding the best growing spot for walnut and Swedish whitebait. These trees would be used by the military to make rifles. The voyage was successful and Linnaeus's observations were published the following year in Skånska resan ("The Voyage to Scania").

Rector of Uppsala University

In 1750, Linnaeus became rector of the University of Uppsala, beginning a period in which natural sciences were specifically appreciated. Perhaps Linnaeus's most important contribution during his tenure in Uppsala was teaching; many of his students traveled to various parts of the world to collect botanical samples. Linnaeus called the best of these students “his apostles.” His classes were usually very popular, and he often held them in the botanical garden. He tried to teach students to think and not trust anyone, not even him. Even more popular than the lectures were the botanical excursions held every Saturday during the summer, in which Linnaeus and his students explored the flora and fauna in the vicinity of Uppsala.

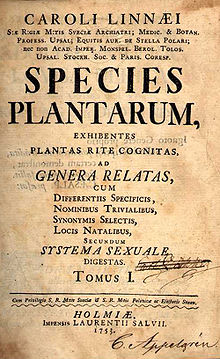

Publication of Species Plantarum

Linnaeus published Philosophia Botanica in 1751. The book contained a complete survey of the system of taxonomy that Linnaeus had been using in his earlier works. It also contained information on how to keep a travel journal and how to maintain a botanical garden.

In 1753, Linnaeus published Species Plantarum, which was internationally accepted as the beginning of modern botanical nomenclature along with his earlier work Systema naturæ. The book, which described more than 7,300 species, ran to 1,200 pages and was published in two volumes.The same year, he was knighted in the Order of the North Star by the king. Linnaeus was the first civilian in Sweden to become a knight of this order. Since then, he has rarely stopped wearing the distinction.

Ennoblement

Linnaeus felt that Uppsala was too noisy and unhealthy and bought two farms in 1758: Hammarby and Sävja. The following year, he bought a neighboring farm, Edeby. Together with his family, he spent summers in Hammarby, at first in a small house, which was extended with a new, larger main building in 1762. At Hammarby, Linnaeus built a garden where he could grow plants that could not be grown in the Uppsala botanical garden. In 1766, he began building a museum on a hill behind Hammarby, where he moved his library and a collection of plants. The reason for the move was a fire that destroyed almost a third of Uppsala and threatened the residence of Linnaeus. Today, this residence is part of a hamlet near Uppsala, known in Swedish as "Linnés Hammarby".

Since the initial publication of Systema naturæ in 1735, the book had been enlarged and reprinted several times; the tenth edition, published in 1758, was later established as the starting point for zoological nomenclature, the equivalent of Species Plantarum. 1757, but was not effective until 1761. He took the name "Carl von Linné". The family's noble coat of arms features, pre-eminently, a Linnaea , one of Linnaeus' favorite plants, to which Gronovius gave the scientific name Linnaea borealis in his honor. The coat of arms is divided into thirds: red, black and green, by the three kingdoms of nature (animal, mineral and vegetable) in Linnaeus's classification; in the center there is an egg "to denote Nature, which is continued and perpetuated in ovo".

Last years

Linnaeus was relieved of his duties at the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences in 1763, but continued his work as normal for more than ten years. In December 1772, he resigned as Rector of the University of Uppsala, mainly because of his health. it was starting to get worse. Linnaeus's last years were hard due to his health; in 1764 he suffered from a disease called Uppsala fever, which he survived thanks to Rosen's care; he suffered from sciatica in 1773, and the following year he had a stroke that would leave him partially paralyzed.In 1776, he suffered a second stroke that caused him to lose the use of his right side and affected his memory of he; while he was still able to admire his own writing, he could not acknowledge that he was the author.

In December 1777, he had another stroke that severely weakened him, killing him on 10 January 1778 in Hammarby. Although he wanted to be buried in Hammarby, he was buried in Hammarby Cathedral. Uppsala on January 22. His library and collections were left to his widow Sara and their children. Some time before, the English botanist Sir Joseph Banks had wanted to buy the collection, but Carl refused, moving it to Upsala. However, when Carl died in 1783, Sara tried to sell the collection to the Banks; However, they were no longer interested in it, so it was acquired by an acquaintance of theirs, James Edward Smith, a 24-year-old medical student, who got hold of the entire collection: 14,000 plants, 3,198 insects, 1,564 shells, approximately 3,000 letters and 1,600 books. Smith formed the Linnean Society of London five years later.

Taxonomy

Linnaeus's initial research in botany prompted him to introduce a new classification of plants based on their reproductive system but he found the new system insufficient. In 1731 he created a system of binomial nomenclature to classify living beings: the first word indicated the genus, followed by the name of the species. Likewise, he was the one who grouped the genera into families, these into classes and the classes into kingdoms. This system allowed him to typify and classify more than 8,000 animal species and 6,000 plants. In 1753 he published « The species of plants » ( Species plantarum ), a work that began the modern nomenclature in biology.

For this reason he was considered the creator of taxonomy, despite the pioneering works of J. P. de Tournefort (1656-1708) and John Ray (1686-1704) with his Historia plantarum generalis.

He was also the first to use the symbols ♂ (the shield and spear of Mars), and ♀ (the mirror of Venus) to respectively indicate male and female.

Linnaeus's conception of the human being

According to German biologist Ernst Haeckel, the question of the origin of man began with Linnaeus. He described humans just as he described any other plant or animal, helping future research into the natural history of man.Linnaeus was the first to place humans in a biological classification system. He placed humans under Homo sapiens , among the primates, in the first edition of Systema naturæ . During his stay at Hartecamp, he had the opportunity to examine some monkeys, identifying some similarities between them and man. He noted that the two species basically have the same anatomy, and found no other differences with the exception of speech. He therefore placed man and apes under the same category, Anthropomorpha, a term meaning "in human form". This classification was criticized by other botanists, such as Johan G. Wallerius and Jacob Theodor Klein, who believed that humans could not be placed under the category "in human form." They were also concerned that they would put themselves on the same level as the monkeys, lowering man from a higher spiritual position. Classification as such also posed another problem for religious people. The Bible says that man was created in the image of God, and if monkeys and humans were related, it would be interpreted that monkeys also represented the image of God, which many could not accept.

After this criticism, Linnaeus understood that he needed to explain himself more clearly. In the tenth edition of Systema naturæ (1758), he introduced new terms, including Mammalia and Primates, the latter replacing Anthropomorpha. The new classification received less criticism, but many natural historians felt that, being a mere part of nature, humans had been degraded from their previous position, in which they held a position of government. However, Linnaeus believed that man, biologically, belonged to the animal kingdom, and that this is how it should be. decrees that man has a soul and that animals are mere mechanical automata, but I think it would be better to teach that animals have souls and that the difference is in nobility."

Linnaeus also added a second species of Homo to Systema naturæ, Homo troglodytes or cave man. This inclusion was based on Bontius's (1658) description and illustration of an Indonesian or Malay woman and the description of an orangutan. Most of these new human species were based on myths or tales of people. who claimed to have seen something similar to a human. Most of these tales were scientifically accepted, and in the early editions of Systema naturæ many mythical animals were included, such as the hydra, phoenix, satyr, and unicorn. Linnaeus put them under the Paradox category; according to the Swedish historian Gunnar Broberg it was to offer a natural explanation and demystify the world of superstition. An example of this is that Linnaeus was not satisfied with just classifying, but also tried to find out, for example, if Homo troglodytes actually existed, so he asked the Swedish East India Trading Company to find a copy. He requested that, if they could not find it, they at least obtain signs of its existence. Broberg believes that the new human species described by Linnaeus were in fact monkeys or native people who wore fur to scare off settlers, and that the description of their aspect was exaggerated until reaching Linnaeus.

In 1771, Linnaeus published another name for a non-human primate in the genus Homo, Homo lar, now Hylobates lar (Linnaeus, 1771), the white-handed gibbon.

Main works

(date indicates first edition)

- Præludia sponsaliarum plantarum (1729)

- Fundamenta botanica quae majorum operum prodromi instar theoriam scientiae botanices per brief aphorismos tradunt (1732)

- Systema naturæ (1735-1770) [Systema naturæper regna tria naturæ, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis], with 13 edited and increased editions.

- Linnaeus, C. (1758). Systema naturæ: per regna tria naturaæ, secundum classes, ordines, generate, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. (in Latin). Take 1. Editio Decima Reformata. 1-824. Holmiæ (Estocolmo): Impensis Direct Laurentii Salvii. Available in Biodiversitas Heritage Library. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.542.

- Linnaeus, C. (1766). Systema naturæ: per regna tria natura, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis (in Latin). Volume 1 Part 1. Ed. 12, reform.. Holmiæ (Estocolmo): Impensis Direct Laurentii Salvii. Available in Biodiversitas Heritage Library. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.68927.

- Fundamenta botanica (1735)

- Bibliotheca botanica (1736) [Bibliotheca botanica recensens books plus mille de plantis huc usque editos secundum systema auctorum naturale in classes, ordines, genera et species]

- Critica botanica (1736)

- Genera plantarum (Ratio operis) (1737)

- Corollarium generum plantarum (1737)

- Flora lapponica (1737) [Flora lapponica exhibit plants per Lapponiam Crescentes, secundum Systema Sexuale Collectas in Itinere Impensis]

- Ichthyology (1738), in which he published the works of Peter Artedi, accidentally deceased.

- Classes plantarum (1738), in Bibliotheca Augustana

- Hortus Cliffortiana (1738)

- Philosophia botanica (1751)

- Metamorphosis plantarum (1755)

- Flora svecica exhibits plants per Regnum Sveciae crescentes (1755)

- Animalium specierum, Leyde: Haak, (1759)

- Fundamentum fructificationis (1762)

- Fructus esculenti (1763)

- Fundamentorum botanicorum parts I et II (1768)

- Fundamentorum botanicorum tomoi (1787)

Eponymy

In addition to numerous botanical and zoological references with his name, one must:

- The lunar crater Linné bears this name in his memory.

- The asteroid (7412) Linnaeus also commemorates its name.

Honorary Distinctions

Fonts

References

Contenido relacionado

Fields closed

Egyptian hieroglyphs

Antibody