Charles I of Spain

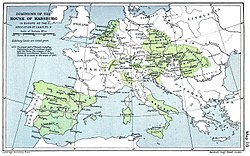

Charles I of Spain and V of the Holy Roman Empire (Ghent, County of Flanders, February 24, 1500-Cuacos de Yuste, September 21, 1558), called « el César", he reigned together with his mother, Juana I of Castilla —the latter only nominally and until 1555—, in all the Hispanic kingdoms and territories under the name of Carlos I from 1516 to 1556, bringing together thus for the first time in the same person the crowns of Castile —the Kingdom of Navarre included— and Aragon. He was Holy Roman Emperor as Charles V from 1520 to 1558.

Son of Juana I of Castile and Felipe I el Hermoso, and paternal grandson of Emperor Maximilian I of Habsburg and Maria of Burgundy, from whom he inherited the Burgundian patrimony and the Archduchy of Austria with the right to the imperial throne of the SIRG, and through the maternal line of the Catholic Monarchs, Isabella I of Castile and Fernando II of Aragon, from whom he inherited the crown of Castile, with the domains in Navarra and the West Indies, and the crown of Aragon that included the kingdoms of: Naples, Sicily, Sardinia, Valencia, Mallorca and Aragon, and the Principality of Catalonia.

Biography

The Young Prince

The birth of Carlos de Habsburgo occurred during the celebration of a dance in the Casa del Príncipe palace (Prinsenhof) in Ghent, Flanders, when the pregnant Archduchess Doña Juana began to feel severe pain in her belly for which she was born in a toilet, which meant that his birth was not witnessed by numerous witnesses who would legally identify the newborn, thus avoiding any doubt about the legitimacy of the future Heir. She wanted to name him Juan in memory of his deceased brother, but he was finally baptized as Charles at his father's wish and in memory of his great-grandfather, Charles the Bold, who died at the Battle of Nancy in 1477. The christening, held on 7 March, was officiated by the Bishop of Tournai, Pierre Quick, in Saint Bavo's Cathedral. Margarita de Austria, wife of the late Prince Juan, and Margarita de York, wife of Carlos the Bold, attended as godmothers, and Carlos de Croy, prince of Chimay, and the lord of Vergás as godparents.

Before he was a year old, Philip made Charles Duke of Luxembourg and Knight of the Burgundian Order of the Golden Fleece. On November 16, 1501, Philip and Joan left for Spain to be sworn in by the Cortes as successors to the Catholic Monarchs and left Carlos in the care of Margarita de York. During his stay in France, Felipe met with King Louis XII and agreed to the marriage between his daughter, Claudia, and Carlos, a deal that was renewed with the signing of the Treaty of Blois years later. After Felipe's return to Flanders and due to the advanced age of Margarita de York, he left Carlos in the care of Mrs. Ravenstein, Ana de Borgoña; He also named his godfather, Carlos de Croy, a gentleman of Carlos's chamber, and entrusted his education to Burgundian teachers who would teach him the history of the duchy. For his part, back in Castile, Fernando the Catholic, aware that Carlos could one day occupy his throne, sent the humanist Luis to Flanders to teach him Spanish and Spanish customs, although when the prince arrived in Spain years later he still had not he mastered this language.

In early 1506 Philip and Juana set out again for Spain to claim the crown of Castile after the death of Isabella the Catholic, but their joint reign was short-lived as Philip died prematurely in September. Fernando, having considered that her daughter was a prisoner of madness, ordered her to be locked up in the Royal Palace of Tordesillas and became her regent. Due to Carlos's minority, his grandfather Maximilian I of Habsburg assumed the regency of the Netherlands, although shortly after he handed over the position to his daughter Margaret of Austria, along with the guardianship of Carlos and his brothers. All of the young prince's education took place in Flanders, specifically in the city of Mechelen from where his aunt Margarita of Austria served as regent and had been in charge of raising her until she came of age. In 1509 the emperor arranged for William de Croy, Lord of Chiévres, to replace his cousin Charles de Croy as gentleman of the prince's chamber, and Hadrian of Utrecht, dean of the University of Louvain and future Pope Hadrian VI, was appointed his teacher.

On January 5, 1515, Guillermo de Croy managed to get the emperor to declare Charles to be of legal age; Immediately afterwards, the General States named Lord of the Netherlands to the young prince, ending here the regency of his aunt Margarita. However, without his own will to govern, the young sovereign would then delegate power to the lord of Chièvres. That same year, Cardinal Adriano of Utrecht traveled to Aragon to ensure that Ferdinand the Catholic would not take away the inheritance of Castile and Aragon from Carlos in favor of his brother Ferdinand I of Habsburg, who had grown up with him and was the favorite grandson. of the. Although he promised to name Carlos as his successor, the king's advisers had to convince him shortly before his death not to appoint Fernando.

Inheritance and patrimony

Titles

Don Carlos by the grace of God King of Romans Emperor Semper Augustus.Doña Joana su madre y el mesmo Don Carlos por la mesmagracia Reyes de Castilla, de Leon, de Aragon, de las dos Sicilias, de Ierusalen, de Navarra, de Granada, de Toledo, de Galicia, de Mallorcas, de Sevilla, de Cerdeña, de Cordova, de Corcega, de Murcia, de Jaen, de los Algezira, de Gibraltar,

Counts of Barcelona,

Lords of Vizcaya and of Molina,

Duchess of Athens and Neopatria,

Counts of Ruysellon and Cerdenia,

Marquis de Oristan e de Gorciano,

Archdukes of Austria,

Dukes of Burgundy of Bravante.Pragmatic or Edict of the Emperor against the comuneros given in Worms (February 1521).

King of Spain

Succession of Ferdinand the Catholic

On January 22, 1516, Prince Charles's grandfather, Ferdinand II of Aragon, wrote his last testament. In it, he named him Governor and Administrator of the Kingdoms of Castilla and León, in the name of Queen Juana I of Castilla, incapacitated by her illness. With regard to the Crown of Aragon, King Ferdinand left all his states to his daughter Juana, naming Carlos Governor-General in his mother's name, also in this case. Until Carlos arrived, Cardinal Cisneros would rule in Castile and Archbishop Alonso de Aragón in Aragon.

On January 23, King Ferdinand died in Madrigalejo (present-day Extremadura). From then on, Carlos began to think about taking the title of king, advised by his Flemish advisers. This decision was not well seen in the Iberian Peninsula. The Council of Castilla sent him a letter on March 4 in which he asked him to respect the titles of his mother, since "that would be to take away the son's honor from the father while he was alive." But ten days later the funeral ceremonies for King Ferdinand ended with shouts of:

Long live the Catholic kings Doña Juana and don Carlos his son. Alive is the king, alive is the king, alive is the king

On March 21, Carlos sent a letter to Castile informing of his decision to call himself King. After lengthy deliberations by the Council, on April 3, Cardinal Cisneros informed the kingdom of Carlos' decision. On the 13th of the same month, the new royal title was reported:

Doña Juana and don Carlos his son, queen and king of Castile, of León, of Aragon, of the Two Sicilies, of Jerusalem, of Navarre, of Granada, of Toledo, of Galicia, of Mallorca, of Seville, of Sardinia, of Córdoba, of Cordoba, of Murcia, of Jaén, of the Algarves, of Algeciras, of Gibraltar, of the islands of the Canary Islands,

In May, the three estates of the Kingdom of Navarre, meeting at the request of Viceroy Antonio Manrique de Lara, swore allegiance to Carlos as their king and natural lord.

Meanwhile, in the Crown of Aragon the situation was chaotic. The Justice of Aragon prevented Archbishop Alonso de Aragón from governing, alleging that, according to Aragonese laws, the position of governor could only be exercised by the heir to the Throne. The Royal Court of Aragon sided with Justice, but ruled that the archbishop could govern as Queen Juana's curator. But the Justice did not allow it then either, claiming that Juana was no longer her heir, since when she was sworn in as such, it was included that if the king had a male child, he would become the heir. And, therefore, as in 1509 Fernando had had a son with Germana de Foix, Juana's oath was annulled (despite the fact that the child had died a few hours later). On May 13, Carlos recognized the archbishop's powers as Queen Juana's curator, but, even so, he was refused to take the oath. On the other hand, the Provincial Council of the Kingdom of Aragon recognized Juana as heir to the Crown, but since she could not reign due to her illness, she had to be removed from the government so that her son could reign. Added to all this was the fact that no institution of the Crown of Aragon recognized Carlos as King until he swore the privileges and liberties of the Kingdoms.

In the Kingdom of Naples, Viceroy Ramón de Cardona received the news of the death of King Ferdinand through the Archbishop of Zaragoza, he was confirmed as Viceroy by Prince Charles from Brussels, on February 11, and had the Juana and Prince Carlos as kings on February 20. Regarding the kingdom of Sicily, before the death of Fernando el Católico, the viceroy of Sicily, Hugo de Moncada, dissolved a Parliament hostile to a new donation to remain in the position until the confirmation of the new king Carlos, but an important part refused to dissolve, not recognizing Carlos as the successor of Fernando, but his mother Juana. On March 5, after celebrating the funeral of the deceased monarch, the uprising took place. They considered that once the king died, the viceroy automatically ceased, they raised banners for Queen Juana and constituted a regency. A new Parliament entrusted the regency of the kingdom to the Marquis of Geraci, Simone Ventimiglia, and to the Marquis of Licodia, Matteo Santapau, and only the city of Messina remained faithful to the viceroy and King Carlos.

In view of this situation, the viceroy of Naples, Ramón de Cardona, intervened, obtaining an agreement between the parties so that they would travel to Carlos' court, while the government of Sicily was in charge of Diego del Águila. Finally, the new viceroy appointed was Ettore Pignatelli, Count of Monteleone. However, the position of the Crown was weakened, and in July 1517, a conspiracy that tried to change the political situation of the kingdom failed when the assassination of the king was not carried out. viceroy, which led to a broader revolt known as the Squarcialuppo rebellion to demand order and justice. Ultimately, the situation was put in order, and in the Parliament of 1518, Charles was recognized as king of Sicily. Regarding the kingdom of Sardinia, an extraordinary meeting of the estates recognized the new sovereigns Carlos and Juana, and in June 1518 a delegation of the royal estate in the Cortes of Zaragoza swore allegiance to the new monarch, although it cannot be verified if representatives were with them. of the other two estates. In October the king granted powers to his viceroy in Sardinia, Ángel de Vilanova, to convene Parliament and collect the oath of allegiance and thus formalize the act partially formulated in Zaragoza.

In the Netherlands, on February 19, 1516, upon the death of Ferdinand the Catholic, William de Croy, lord of Chièvres, requested 400,000 gold florins for the future trip to Spain, which was approved by the States General of the Netherlands, but in return Carlos had to leave the pacified territory. In this way, he agreed to the Treaty of Noyón with Francisco I of France, and since the acquisition of the rights over Friesland left an open front with Carlos de Egmond, Duke of Güeldres, a peace treaty was agreed on September 17, 1517. In June 1517, Charles informed the Estates General meeting in Ghent that the government in his absence would be in charge of a Privy Council chaired by his aunt, the Archduchess Margaret of Austria, and his grandfather, the Emperor Maximilian, as its supervisor in in case communication with Spain could not be carried out. And in July he appointed Filiberto de Chalôns as Governor and Lieutenant General in the counties of Burgundy and Charolais.

Charles secured his position as king thanks to Pope Leo X's recognition as king in the bull Pacificus et aeternum of April 1, 1517, and on September 8, 1517, Charles He left with his squad from Vlesinga, at five in the morning, heading to Santander. But a strong storm diverted the course of the ships, and in the early morning of September 19, 1517, Saturday, the forty ships that made up the squadron found themselves off the coast of Villaviciosa. When the error in the course was discovered, Carlos and his advisers deliberated on whether to continue the voyage by sea or disembark right there. The insecurity of the sea route, "because of the mutability of the wind, which can change the same thing for good or bad", inclined the decision towards disembarkation, according to Laurent Vital, the Flemish chronicler who was traveling with the king. They finally disembarked in the Asturian port of Tazones. The next stage of the trip was in Tordesillas, where he visited his mother, Queen Juana la Loca, very briefly on November 4, 1517, confined there, where Chièvres obtained from the queen Juana the act by which she recognized her son Carlos to govern in her name, so that in this way the appearance of legitimacy was given to the seizure of power by Carlos. Already in Valladolid, she received the news of the death of the Cardinal Cisneros, which left the government of Castile completely flattened.

On February 9, 1518, the Cortes of Castile, meeting in Valladolid, swore Carlos along with his mother Juana as king and granted him 600,000 ducats. In addition, the Cortes made a series of requests to the king, among them:

- Learn to speak Spanish.

- The cessation of appointments to foreigners.

- The ban on the exit of precious metals and horses of Castile.

- I treat her mother Juana more respectful, in Tordesillas.

In Aragon the situation was still complicated. Carlos arrived in Zaragoza on May 9. The sessions of the Courts of Aragon began on May 20 and after long discussions, on July 29 Carlos was sworn in as King of Aragon. Juana was recognized as Queen, but due to her inability to govern, her titles remained only "nominal". She was also given 200,000 pounds.

On February 15, 1519, Carlos entered Barcelona, summoning the Catalan Parliament the following day. After a speech very similar to the one he gave in Aragon, and the corresponding deliberations, Carlos was sworn in together with Juana on April 16. The question of the money that the Cortes had to contribute lasted until the beginning of January 1520, when they finally granted him 300,000 pounds.

Meanwhile, Emperor Maximilian I died on January 12, 1519. On June 28, Charles was elected King of the Romans in Frankfurt am Main, making him the new sovereign of the Holy Roman Empire, and For this reason, he decided to suspend the trip to Valencia to go to Germany, previously convening the Castilian Cortes in Santiago de Compostela for March 20, 1520. In this way, Carlos sent Hadrian of Utrecht so that through him they would swear him as king and could convene Cortes in Valencia, despite the illegality, which caused discomfort among the privileged classes; however, due to the disputes between the noble (military) and ecclesiastical arms against the Germanías, the Cortes did not come to be held, and in view of the disturbances, the king sent a document on April 30, 1520 offering to keep his privileges and privileges. Finally, the king complied with the foral legality and before going to the General Courts of Monzón, convened on June 1, 1528, he passed through Valencia and swore his privileges on May 16 of that year.

After this long process that lasted four years (not counting the oath in Valencia), Carlos became the first monarch to hold the crowns of Castile, Aragon and Navarra.

Conflicts in Castile: the Communities (1520-1521)

The arrival of Carlos to Castile meant the arrival of an inexperienced young man who did not know the customs and language of his kingdom, given which he placed his trust in his Burgundian collaborators who had accompanied him from the Netherlands, to whom he provided high dignities and access to income and wealth. This annoyed the Castilians and they were informed of this in the Cortes of Valladolid in 1518, which was ignored by the king. The king immediately went to Aragon. In the long run, this annoyed the Castilians, since in Castile he had stayed much less time, so when he found out in Barcelona that he had been elected King of the Romans, he summoned the Cortes of Santiago and La Coruña to obtain subsidies to cover his expenses in the foreign. The cities opposed it, since they did not understand the preference of the interests in Germany over the Castilians and required their presence in the kingdom. Finally the service was accepted and Carlos embarked for Germany, naming Cardinal Adriano of Utrecht as regent.

The unrest spread throughout Castilla, and the fire in Medina del Campo spread the focus of the community rebellion throughout Castilla. The anti-seigneurial revolts caused the nobility to support the emperor, and the movement was losing acceptance in the cities. Finally the community members, under the command of Padilla, Bravo and Maldonado, were defeated in the battle of Villalar, and the king on his return made organizational changes in the kingdom that were manifested above all after the Cortes de Valladolid in 1523. Despite his victory, the community movement still lasted in some population centers, with greater or lesser success. The city of Toledo championed all that resistance in the figure of María Pacheco.

Conflicts in Aragon: the Germanías (1520-1523)

The Germanías movement took place in the territories of the Kingdom of Valencia and Majorca. The artisans of Valencia had the privilege of the reign of Fernando el Católico to form militias in case of need to fight against the Barbary fleets. In 1519 Carlos I allowed the formation of these militias and they were placed under the command of Joan Llorenç.

In 1520 when a plague epidemic occurred in Valencia and the nobles abandoned the area, the militias seized power and disobeyed Hadrian of Utrecht's order for their immediate dissolution. In a few days the movement reached the Balearic Islands where it lasted until 1523. After the defeat of the comuneros, the army ended the conflict of the Germanías.

The Navarre War

Taking advantage of the War of the Communities of Castile with a partial demilitarization of the Kingdom of Navarra, the third counter-offensive of the Navarrese took place to recover the kingdom in 1521. On this occasion, Enrique II of Navarre with the support of the French king Francisco I, he achieved recovery in a short time. However, the humble population remained almost entirely passive, without showing loyalty to Carlos I but without showing support for the legitimists. As for the aristocracy, many had encouraged the uprisings that had facilitated the operation, but the rest had sworn allegiance to Carlos I. Therefore, the Navarrese legitimists depended almost totally on French military and economic support, which left them in a situation Very fragile strategy. In a short time, the strategic errors of the French general André de Foix and the rapid recomposition of the Spanish army led to a military disaster in the battle of Noáin.

As the legitimists lacked solid support among the common people or the elites, the Spanish reconquest of almost all of Navarre was very rapid. Only pockets of resistance remained in border regions such as the Baztán-Bidasoa area, producing historic confrontations and sieges such as the Maya castle, the battle of Mount Aldabe or the siege of the Fuenterrabía fortress. Finally, the diplomatic route, granting a broad amnesty, and the resignation of Lower Navarre, which he did not manage to control militarily, led to the Emperor gaining control of Upper Navarre. However, in the long term the decisive factor was that the kings of France gave up supporting Navarrese legitimism as a weapon against Spain.

The organization of the Hispanic Monarchy

With the return of King Carlos I to Castile in September 1522, a series of reforms were undertaken to integrate the social elites into the government and administration of the Monarchy, which would be completed by his son King Felipe II constituting the polisynodial system. of advice. The structure of the polisynodial regime of the Councils can be found in the Curia Regis which in 1385 became the Royal Council, or Council of Castile, with the tasks of advising the king, processing ordinary administrative matters and exercise of justice. Due to the increase and diversity of issues to be discussed, in the time of the Catholic Monarchs the Council had been divided into sections that would become independent Councils, in 1494 the Council of Aragon was established, in 1483 the Council of the Inquisition, in 1498 the Council of Orders, and in 1509 the Council of the Crusade, but it would be Carlos I who gave the impetus to the system of Councils.

Once the armed uprising of the community members had been subdued and the supremacy of royal power assured, the great chancellor Gattinara proposed to Carlos I a Secret Council of State that would have supremacy over the other Councils and would be the regulatory and supervisory axis of global politics, in which he himself would be the president; for this purpose he undertook in 1522 the rationalization of the Spanish administration with the reform of the existing Councils and the creation of the Finance Council in 1523, but The king did not want to depend on a single minister and such a project to centralize in a single Council was rejected, so the influence of the Grand Chancellor, who after all was a position of Burgundian origin, gradually eclipsed in front of Francisco de los Cobos, and consequently he was critical of the collegiate and fractional administrative planning that was carried out in those years of 1523-1529. In 1524 the Council of the Indies was constituted and in 1526, the Council of State, not as Gattinara had devised it but as a private council of the monarch, hence it did not have a president or fixed residence in the time of Carlos. The other councils were established in Valladolid, which became the administrative capital until 1561.

The Councils were made up of people personally chosen by the king (compliance with a series of unwritten rules when choosing them) who, under the presidency of the king himself or some representative of his (most of the times) discussed about any topic. The king always had the last word, but it is not impossible to understand the power they accumulated: first, because the Council was the place where the king weighed the positions of various noble, ecclesiastical or courtly factions. Second, because in times when the monarch was not able (disease, war, etc.), they were the true rulers in his sphere of action. Third, because, at that time, the legislative, executive or judicial powers were not strictly separated, so the Councils became a kind of Courts of Appeal; Fourth, because certain Councils had worldly and spiritual tasks together, which is why they used to have the keys to social prestige (Council of Orders, to name the clearest case), significant economic income (Council of Crusades) or political key (Council of the Inquisition).

In this order, the important work of the secretaries stands out. Aside from the Chancellery, which disappeared with the death of Gattinara in 1530, the king dispatched with his secretaries, who normally held the secretaries in the Councils, since after all, the secretaries were in charge of transferring the King the deliberations of the Councils and of transferring to the members of the Council the decisions and resolutions of the King, which avoided a paralysis in the government, allowing the system to work. However, their power went beyond this, since they became in the true managers of the Royal will: their transcriptions depended on the accuracy with which the monarch perceived the declarations of the members of the Councils, they accelerated or delayed the delivery of the deliberations to the monarch, they controlled the ordinary correspondence and they made the decisions preparing the documents for the signature and trafficked with the privileged information they had and with their ability to access the monarch.

His reign in America

During the reign of Carlos I, the crown of Castile expanded its territories over much of America:

- Hernán Cortés conquered the Mexican Empire in 1521, which would give rise to the Kingdom of New Spain

- Nuño de Guzmán conquered the Tarasco Empire and the lordships that formed the Kingdom of New Galicia, in the middle of the XVI

- Francisco de Montejo would begin the long process of conquest of the Mayas of the Yucatan peninsula, in the centuryXVI

- Pedro de Alvarado conquered the Central American territories that would give rise to the Kingdom of Guatemala,

- Francisco Pizarro conquered the Inca Empire that would give rise to the Virreinate of Peru

- Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada conquered the Muiscas and their confederation, in the current Colombia, founding the New Kingdom of Granada.

- The Spanish captains Sebastian de Benalcázar and Francisco de Orellana left the Kingdom of Quito in search of the mythical El Dorado. Benalcázar founded the city of San Francisco de Quito in 1534, while Orellana, after founding Guayaquil, stepped into the Amazon and discovered the Amazon River.

- Juan Sebastián Elcano made the first round of the world in 1522, finishing the journey that began Fernando de Magallanes and laying the first bases of Spanish sovereignty in the archipelagos of the Philippines and the Marianas.

Through the Capitulation of Madrid in 1528, King Charles temporarily leased the province of Venezuela to the German Welser family of Augsburg, which led to the creation of the Klein-Venedig, one of the German governorships in America.

On August 24, 1534, Diego García de Moguer, traveled on a second expedition to the Río de la Plata, with the caravel Concepción, passing through the island of Santiago de Cabo Verde, then to Brazil, where it descends the estuary of the Uruguay and Paraná rivers and founds the first settlement of the city of Santa María del Buen Aire. Later Pedro de Mendoza completed the foundation of Buenos Aires on the right bank of the Río de la Plata, being exterminated by the natives. A short time later, Juan de Salazar and Gonzalo de Mendoza founded Asunción, which would become the motor center of the conquest of the River Plate basin, and Pedro de Valdivia founded Santiago de Chile. All this contributed to establishing the first global empire in universal history under the reign of his successor, Philip II, where it was said that "the sun did not set."

Most of the expeditions were private companies, carried out with the permission of Carlos V, but always declaring the sovereignty of the Spanish Crown over all the conquered territories, although these were considered part of the Crown of Castile since 1492, having This kingdom promoted the first exploration and conquest expeditions of the Indies and the Mainland, a term that includes the Caribbean islands and all of America.

Control over the Church

Between 1508 and 1523 the popes had to grant prerogatives to the kings of Spain or the Hispanic Monarchy; but as early as 1516 they had granted similar privileges to the King of France (by Pope Leo X) and earlier still to the King of Portugal (by the bull Dudum cupientes of Pope Julius II, in 1506). These prerogatives "extended only to bishoprics and consistory benefits".

Later, the monarchs managed to exercise all or most of the powers attributed to the Church in the government of the faithful, becoming, in fact and in law, the highest ecclesiastical authority in the territories under their domain. This is called royal patronage or royal patronage strictu sensu.

The provisions issued by the pope, the apostolic nunciature and the councils had to obtain the royal pass or regium exequator before being published in Spain and its domains. If they were detrimental to the kingdom, the lien was applied and their dissemination was prevented.

Later, Carlos V added to the above the position of Patriarch of the Indies, obtaining control of all the evangelizing work.

Holy Roman Emperor

After the death of his grandfather Maximilian I of Habsburg, Holy Roman Emperor, on January 12, 1519, Carlos reunited in his person the territories from his grandparents' quadruple inheritance: Habsburg (Maximilian I), Burgundian (María de Borgoña), Aragonese (Fernando the Catholic) and Castilian (Isabel the Catholic), although a few years later he renounced the territories of Austria to his brother Fernando.

In competition with King Francis I of France, which entailed an enormous expense that Carlos faced looking for money in Castile and German bankers, such as the Welsers and Fuggers, on October 23, 1520 he was crowned King of the Romans in Aachen and three days later was recognized Holy Roman Emperor Elect. These affairs in Germany absented him from Spain until 1522.

On February 24, 1530, the same day as his birthday, in Bologna, Charles was crowned Holy Roman Emperor by Pope Clement VII, who became an ally of the imperial cause. Previously, two days before, solemnly, but almost privately, so as not to underestimate his imperial coronation, he was crowned King of the Burgundians or King of Italy.

The emperor's ideology was the ideal of humanism of the Universitas Christiana, the supremacy of imperial authority over all the kings of Christendom and the assumption of the defense of Catholicism. This imperial conception was the work of Spanish minds such as Pedro Ruiz de la Mota, Hugo de Moncada or Alfonso de Valdés. In the face of these universalist ideals, the French King Francisco I and the Pope disagreed. Hence he was constantly in struggle with both during his reign.

Against the Ottoman Turks

In 1516, Prince Selim of Algiers asked the privateer Baba Aruj, better known as Barbarossa, for help to get rid of the subjugation of Castile. Aruj went as a friend, but after attacking Algiers and expelling the Spanish from the city, he killed Selim and declared himself king. Cardinal Cisneros, regent of Castile until the arrival of Carlos to the kingdom, sent a troop of 8,000 men under the command of Diego de Vera to reconquer the city, but their lack of military training caused them to be defeated.

In 1517 Aruj seized Tlemecén, a tributary city of the Spanish governor of Orán, the Marquis of Comares Diego Fernández de Córdoba. The following year, he defeated and killed the corsair and his brother Jeireddin proclaimed himself king of Algiers. After hearing the news, Carlos decided to immediately reconquer the city, sending Hugo de Moncada in command of an expedition made up of 7,500 soldiers. The council of war held on August 17 decided to wait for the help offered by the king of Tlemecén, but a strong storm devastated the Spanish fleet seven days later and Hugo de Moncada was forced to withdraw.

In this way, with the help of the Protestant German princes and a large part of the Castilian nobility, in 1532 Carlos came to the aid of his brother Ferdinand of Habsburg to defend Vienna from the attack of Suleiman the Magnificent, a city he He arrived on September 23 of that year, but Francis I of France, who feared that the emperor would defeat the Turks and thus focus on the war against him, advised the sultan not to attack the imperial army and he ended up withdrawing without offering much. battle.

That same year Jeireddín Barbarossa managed to expel the Spanish from the Rock of Algiers and in 1533 he allied with Suleiman, who appointed him admiral of the fleet. The following year the corsair took Tunisia and, faced with this situation, Carlos organized two operations of different fortunes. The first was known as the Journey of Tunis, in 1535, for which Tunisia was taken from Barbarossa and the second, the Journey of Algiers, in 1541, which failed due to bad weather.

The wars with France

Carlos I fought four wars with Francisco I of France, who also aspired to the imperial crown, and who demanded the return of Burgundy.

- In the first war (1521-1526), France took over Milanesado and helped Henry II to recover the Kingdom of Navarre after its conquest in 1512. However the French monarch was defeated and made prisoner, along with the Navarre monarch, in the battle of Pavia (1525). Francisco was taken to Madrid where he signed the Madrid Treaty (1526), for which he would never again occupy the Milanese and would not support the king of Navarre (peace to which he resigned months later for signing it under duress) and would hand over Burgundy to Carlos, in addition to giving up Flandes and Italy.

- In the second war (1526-1529) the imperial troops raided and looted Rome (Saco of Rome), forcing Pope Clement VII, ally of Francis I—after the League of Cognac—to take refuge in the castle of Sant'Angelo. Through the Peace of Cambrai, Carlos I resigned from Burgundy in exchange for Francisco I to give up Italy, Flanders and Artois, in addition to delivering the city of Tournay. Crowned by the Pope as emperor of the Holy Roman Empire (1530), Charles I continued his struggles against France.

- The third (1535-1538) was due to the French invasion of the Duke of Saboya, ally of the Habsburg monarchy, with the intention of continuing to Milan. It ended with the signature of the truce of Nice due to the exhaustion of both contenders.

- The fourth (1542-1544) concluded due to the resumption of the conflict of Protestants in Germany. Exhausted, the two monarchs signed the Peace of Crépy, by which Carlos I lost territories of northern France — such as Verdun, etc. — and close to Flanders; once again France renounced Italy and the Netherlands, entering Milan into marriage policy through a predictable Spanish-French link.

The Rise of Protestantism

The Catholic Monarchy or Hispanic Monarchy of King Carlos I was completed when the monarch was proclaimed Holy Roman Emperor under the name of Carlos V. The emperor assumed, among other commitments, to convene state assemblies called reunions or diets.

In 1521, at the Diet of Worms, his brother Ferdinand was appointed Regent of the Empire and raised to the rank of Archduke. At the same time the monk Martin Luther, under the protection of the elector Frederick of Saxony, was declared an outlaw, beginning the religious confrontation of Catholicism in order to stop the expansion of Lutheranism. In 1523 he ceded the islands of Malta and Gozo, as well as Tripoli to the Order of Malta. The followers of Luther's doctrine assumed the denomination "Protestants" as soon as they, gathered in "reformed orders", in the course of the second Diet of Speyer in 1529, protested against the decision of the emperor to reinstate the Edict of Worms, an edict that had been suspended at the preceding Diet of Speyer in 1526. As sovereign, after the imposition of the crown of the Empire by the hand of the pontiff in 1530, Charles devoted himself completely to trying to solve the problems that Lutheranism was creating in Germany and in Europe, in order to safeguard the unity of the Christian faith against the onslaught of the Muslim Turks.

In the same year 1530, between June 15 and November 19, he called the Diet of Augsburg, in which Lutherans and Catholics faced each other over the so-called Augsburg Confessions. At this Diet Melanchthon attended, as a representative of Luther. He made concessions, but was intransigent in the marriage of priests, communion under both species and the rejection of private masses. Carlos confirmed the Edict of Worms of 1521, that is, the excommunication for Lutherans, threatening the reconstitution of ecclesiastical property. In response, the Lutherans, represented by the so-called "reformed orders", acted by giving life to the Schmalkaldic League in 1531. Such a coalition, endowed with an army and a common treasury, was also called the "League of Protestants".

In the year 1532 the Diet of Regensburg did not reach an agreement between Catholics and Protestants either. According to the historian Joseph Pérez, Carlos V considered, at all times, the Protestants as heretics and rebels and if he could not apply a much harsher repression it was because the political system of the German Empire prevented him from doing so. Recognizing that a reform was necessary and to try to solve the problem, the pontiff Paul III called the Council of Trent. Council officially initiated on December 5, 1545 and concluded long after the disappearance of the pope who called it and Emperor Charles V.

After the Protestants refused to recognize the Council of Trent, the emperor began the war in June 1546, after signing the Peace of Crépy (1545) with France and reaching a truce with the Turks in Europe central. The Catholic armies were composed of an army armed by the pontiff, under the command of Octavio Farnesio, another Austrian commanded by Ferdinand of Austria and another by the soldiers of the Netherlands under the command of the Count of Buren. He also supported Caesar Maurice of Saxony who had cleverly been removed from the Schmalkaldic League. In summary, the Emperor managed to gather some 40,000 men led by the Duke of Alba, compared to 60,000 for the Lutheran troops, although the lack of funds and a confrontation that dragged on over time reduced the Emperor's forces to 25,000 men.; Despite everything, Carlos V achieved a resounding victory in the battle of Mühlberg, in 1547; soon after, the German princes withdrew and made themselves subservient to the emperor. The Augsburg diet of 1548 resulted in an imperial decree known as the Augsburg interim, to govern the Church pending the resolutions of the Council. In the meantime, Catholic doctrine was respected, but communion by both species and the marriage of the clergy were allowed.

Following the imperial victory in the Schmalkaldic War (1546-1547), the defeated Protestant princes were dissatisfied with the religious terms of the Augsburg Interim. In January 1552, led by Maurice of Saxony, a few allied with King Henry II of France by the Treaty of Chambord (1552). In exchange for French financial support and assistance, Henry was promised possession of the Three Bishoprics—Metz, Verdun, and Toul—as Vicar of the Empire. Unleashed the war with the Protestant princes and before the advance of Mauricio de Saxony, Carlos had to flee to Carinthia, while Enrique took the fortresses of Metz, Verdun and Toul. Carlos's brother, Fernando, negotiated peace with the Passau Treaty (1552), by which the emperor guaranteed freedom of worship to Protestants.

Despite his victory, he did not achieve the cherished desire of politically and socially unifying Lutheranism with Catholicism, for which reason shortly after, in 1555, he was forced to sign the Peace of Augsburg, by which he recognized German princes the right to freely adhere to the Catholic confession or to Lutheranism, ending, even temporarily (fifty years), the long conflict that arose from the Counter-Reformation.

The discouragement that occurred after the failure of the emperor to contain the Protestant reform in the German Empire was at the base of his abdication (1555) and the division of his inheritance, separating the German Empire from the rest of the territories, ceding it to him to his brother Fernando and creating two dynastic lines for the Habsburgs, the Spanish line and the Austrian line. The Empire would become a mere confederation of territories. The Peace of Augsburg (1555) was confirmed by the Peace of Westphalia a hundred years later, in 1648, which ended with the Thirty Years' War.

Abdication, retirement, death and transfer of remains

After so many wars and conflicts, Carlos entered a phase of reflection: about himself, about life and his experiences, and also about the state of Europe. The great protagonists, who together with him had shaped the European scene in the first half of the XVI century, had died: Henry VIII of England and Francis I of France in 1547, Martin Luther in 1546, Erasmus of Rotterdam ten years earlier, and Pope Paul III in 1549.

The balance of his life and what he had completed was not entirely positive, especially in relation to the goals he had set for himself. His dream of a universal Empire under the Habsburgs had failed, as had his goal of reconquering Burgundy. He himself, although calling himself the first and most fervent defender of the Roman Church, had not been able to prevent the establishment of the Lutheran doctrine. His overseas possessions had increased enormously, but his governors had not been able to establish stable administrative structures. But he had consolidated Spanish rule over Italy, which would be secured after his death with the Peace of Cateau-Cambrésis in 1559 and would last for one hundred and fifty years. Carlos began to be aware that Europe was on its way to be governed by new princes, who, in the name of maintaining the States themselves, did not attempt to alter the political-religious balance within each of them in the slightest. His conception of the Empire had passed and Spain was consolidating as a hegemonic power.

In the abdications of Brussels (1555-1556), Carlos left the imperial government to his brother Ferdinand (although the voters did not formally accept his resignation until February 24, 1558) and that of Spain and the Indies to his son Philip. He returned to Spain on a boat trip from Flanders to Laredo, with the purpose of curing gout disease in a region that he had been told about because of its good climate and far from large cities, the region of La Vera in Extremadura. It took him a month and three weeks to reach Jarandilla de la Vera, where he stayed thanks to the hospitality of the III Count of Oropesa, Fernando Álvarez de Toledo y Figueroa, who lodged him in his Oropesa castle. There he waited from November 11, 1556 to February 3, 1557, the date on which the works on the palace house that he had built next to the Yuste monastery were completed. In this placid place he remained a year and a half in retirement, away from the cities and political life, and accompanied by the order of the Jerónimos, who spiritually guided the monarch until his last days.

In his will, he recognized Juan de Austria as his son born from the extramarital relationship he had with Bárbara Blomberg in 1545. He met him for the first time in one of the rooms of the palace house of the Yuste Monastery.

Finally, on September 21, 1558, he died of malaria after a month of agony and fever (to which was added gout, a disease he also suffered acutely), caused by the bite of a mosquito coming from the stagnant waters of one of the ponds built by the clock expert and hydrographic engineer Torriani.

In 1573, King Felipe II ordered the transfer of the remains of the late emperor and Infanta Leonor of Austria, Queen of Portugal, to the Monastery of El Escorial, a task that was carried out by the IV Count of Oropesa, Juan Álvarez de Toledo and Monroy. Carlos' coffin is located in the Royal Crypt of the Monastery of El Escorial, known as the Pantheon of the Kings.

Family

Marriage and children

On March 11, 1526, Carlos I married his cousin Isabel of Portugal, granddaughter of the Catholic Monarchs and sister of Juan III of Portugal, in the Real Alcázar of Seville, who in 1525 had married the sister of Charles I, Catherine of Austria. With her he had the following children:

- Philip (21 May 1527-13 September 1598), successor of his father on the throne of Spain (together with his possessions in America, the Netherlands, Milan, Sardinia, Naples and Sicily) with the name of Philip II.

- Mary (21 June 1528-26 February 1603), who in 1548 married the emperor Maximilian II of Habsburg, his cousin brother.

- Fernando (22 November 1529-13 July 1530).

- Juana (24 June 1535-7 September 1573), who in 1552 married his cousin Juan Manuel de Portugal, an infant heir to Portugal.

- John (1 May 1539).

Children out of wedlock

- Isabel de Castilla (1518), daughter of Queen Germana de Foix, widow of Fernando the Catholic and, therefore, grandmother of Charles.

- Margaret of Austria or Margarita de Parma (1522-1596), whose mother was Juana Van der Gheest.

- Joan of Austria (1523-1530), daughter of Catherine of Rebolledo, one of the ladies of Juana la Loca.

- Tadea of Austria (1523?-ca. 1562), whose mother was Orsolina della Penna. She married Sinibaldo di Copeschi.

- John of Austria (1547-1578), whose mother was Barbara Blomberg.

Genealogy

According to research carried out and published at the beginning of 2016 by researchers Gonzalo Álvarez and Francisco Ceballos, from the Department of Genetics of the University of Santiago de Compostela, on the consanguinity of the Spanish Habsburgs, King Carlos I had a coefficient of consanguinity small, 3.7%. His parents were third cousins to each other and descended from the kings Fernando I of Aragon and Juan I of Portugal.

| Ancestors of Carlos I of Spain | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Semblance

The Venetian ambassador Gaspar Contarini gave the following description of Emperor Charles V at twenty-five years of age:

It is of medium stature, but not very large, nor small, white, of color rather pale than blushing; of the body, well proportioned, beautiful leg, good arm, the nose a little stingy, but little; the avid eyes, the grave aspect, but not cruel or severe; nor in it another part of the body can be instilled, except the chin and also all its inner face, which is so long

Powers

Contenido relacionado

Alexander dumas

Tolosa (Guipuzcoa)

Minotaur