Charlemagne

Charlemagne (Latin, Carolus [Karolus] Magnus; April 2, 742, 747 or 748-Aachen, January 28, 814), personal name Charles, as Charles I the Great was King of the Franks from 768, nominal King of the Lombards from 774, and Imperator Romanum gubernans Imperium from 800 until his death.

The son of King Pepin the Short and Bertrada of Laon, he succeeded his father and became viceroyalty with his brother, Carloman I. Although relations between the two became tense, Carloman's sudden death prevented the outbreak of war. He strengthened the friendly relations his father had maintained with the papacy and became his protector after defeating the Lombards in Italy. He fought the Muslims who threatened his possessions in the Iberian Peninsula and tried to seize the territory, although he had to retreat and because of an attack by the Basques, he lost his entire rearguard, as well as Roldán, in the Roncesvalles gorge. He fought against the Slavic peoples. After a long campaign he managed to subdue the Saxons, forcing them to convert to Christianity and integrating them into his kingdom; thus he paved the way for the establishment of the Holy Roman Empire under the Saxon dynasty.

He expanded the various Frankish kingdoms into an empire, incorporating much of Western and Central Europe. He conquered Italy and was crowned Imperator Augustus by Pope Leo III on December 25, 800 in Rome, thanks to the opportunity offered by the deposition of Constantine VI and what was considered the vacancy of the imperial throne, occupied by a woman, Irene. These events provoked the indignation of the imperial court, which refused to recognize his claimed title. After frustrated wedding plans between Charlemagne and Irene, the war broke out. Finally, in 812 Michael I Rangabé recognized Charlemagne as emperor (though not "emperor of the Romans").

Her reign has been commonly associated with the Carolingian Renaissance, a revival of Latin culture and arts through the Carolingian Empire, led by the Catholic Church[citation needed], which established a common European identity. Through his conquests abroad and his internal reforms, Charlemagne laid the foundations of what would become Western Europe in the Middle Ages. Today, Charlemagne is considered not only as the founder of the French and German monarchies, who name him Charles I, but also as "the father of Europe." Pierre Riché writes:

[...] He enjoyed an exceptional destiny, and by the leadership of his reign, by his conquests, legislation and legendary stature, he deeply marked the history of Western Europe.

Chronology of the Carolingian Empire

| The Carolingian Empire (birth until its fall) | Years |

|---|---|

| Pipino, crowned king of the Franks | 751 |

| Queen of Charlemagne | 768-814 |

| Campaign in Italy | 773-774 |

| Campaign in Hispania | 778 |

| Conquest of the Bavarians | 787-788 |

| Charlemagne, crowned emperor. | 800 |

| Final conquest of the Saxons. | 804 |

| Death of Carlomagno and Reinado de Luis el Piadoso | 814-840 |

| Treaty of Verdun dividing the Carolingian Empire | 843 |

Historical context

At the end of the 5th century the Christianization of the Franks took place, through the conversion of their Merovingian king Clovis I. The Merovingian kingdom became, after the battle of Vouillé in 507, the most powerful among the resulting kingdoms the fall of the Western Roman Empire. However, the decline of the dynasty became evident after the Battle of Tertry (687) and no sovereign tried to remedy the situation. Eventually, all governmental powers would be exercised through the major officers or the Maior domus, that is, of the butler.

Pepin of Heristal, steward of Austrasia, ended the conflict between the various Frankish kings and their stewards with his victory at Tertry, after which he became sole ruler of the entire Frankish kingdom. He was the grandson of two of the most important figures in the Austrasian kingdom: Arnulf of Metz and Pepin of Landen. Upon his death, he was succeeded by his illegitimate son Carlos Martel, "the Hammer", who never adopted the title of king. Martel was succeeded by his two sons: Carloman and Pepin "the Short", who would be the father of Charlemagne. In order to curb the separatism present in the periphery of the kingdom, the brothers placed Childeric III, the last Merovingian king, on the throne.

After Carloman's resignation from office, Pepin deposed Childeric with the approval of Pontiff Zacharias, who elected and anointed him King of the Franks in 751. In 754, Stephen II would once again anoint him and his sons, heirs of a kingdom that encompassed most of Western and Central Europe. This is how the Merovingian dynasty was replaced by the Carolingian. The term Carolingian (Medieval Latin karolingi, altered form of Old High German *karling, kerling, meaning 'descendant of Charles', cf. Middle High German kerlinc) derives from the Latinized name of Carlos Martel: Carolus.

Under this new dynasty, the Frankish kingdom extended over most of the territories of Western Europe. The effective administrative division during this time corresponds to the modern countries of France and Germany. Geographically located in the center of Europe, France gave rise to a religious, political and artistic evolution that left its mark on all of Western Europe..

Date and place of birth

His date of birth has generally been set in the year 743. However, various factors have led experts to reconsider this date, since his birth was calculated from the year of his death and in the Annales Petarienses contains another date, April 1, 747, which coincided with Easter. This coincidence was so suspicious that it has been questioned on numerous occasions. Modern historians defend that this date constitutes a farce destined to exalt the figure of the emperor, and suggest that he was born a year later, in 748.

It is currently impossible to know with certainty the date of his birth. The most feasible hypotheses are those of April 1, 747, April 15 of that same year, or April 1, 748. Most hypotheses hold that Charlemagne was born in Herstal, his father's hometown, where they were from. the Carolingian and Merovingian dynasties, and located in the vicinity of the current Belgian city of Liège. When he was seven years old, he went to live with his father in Jupille, which is why in almost all history books that city appears as one of his possible birthplaces. Other cities have also been considered as such, including Ingelheim, Prüm, Düren, Gauting and Aachen.

Language

His native language has been the subject of intense debate. It is presumed that his mother spoke a common Germanic dialect among the Franks of the time; however, linguists differ as to the identity and evolution of the language. It has even been claimed that at the time of his birth (742/747) the Old Frank was already extinct. The syntactic and orthographic structure of Old Frankish has been reconstructed through its evolution: Low Frankish, which influenced Old French and later gave rise to Old Netherlandish. The little knowledge of Old Frankish that linguists have corresponds to phrases and words present in the law codices of the main Frankish tribes, written in a Latin that integrates Germanic elements.

Your place of birth has not helped determine your native language. Many historians have defended that he, like his father, was born in the surroundings of Liège; others affirm that in Aachen, a city located 50 km from the previous one. The issue is complicated by the fact that this area encompasses great linguistic diversity. If you take Liège from the year 750, we find a region in which Low Frankish is spoken in the north and northwest, Gallo-Romance in the south and southwest, and High German dialects in the east. If Gallo-Romance is excluded, Charles would have spoken Old Low Frankish or a High German dialect, probably heavily influenced by Frankish.

In addition to his mother tongue, he spoke Latin "with a fluency similar to that of his own language," as well as understanding a little Greek:

Grecam vero melius intellegere quam pronuntiare poterat.I understood Greek better than he was.Eginardo, Vita Karoli Magni25.

Names of Charlemagne

As a consequence of the number of languages spoken within the Empire, and its expansion on a European scale, the name of Charlemagne has been preserved in abundant forms in a large number of different languages. His own language no longer exists on its own, but evolved into the Frankish language.

"Carlos", his birth name, derives from that of his grandfather, Carlos Martel; This name in turn comes from Karl, a Germanic lexeme meaning 'man' or 'free man', and which is related to the English Churl. The Latin names Carolus or Karolus constitute the earliest extant forms of his name.

In various Slavic dialects, the term "king" corresponds to a derivation of his Slavic name.[citation needed]

The modern variants existing in the languages of Germanic origin are:

- in Danish, Norwegian and Swedish: Karl den Store;

- in Dutch: Karel de Grote;

- in German: Karl der Große;

- in Luxembourg: Karel de Groussen;

- in western fries: Karel de Grutte.

The Germanic name was Latinized—Carolus Magnus—and preserved in modern Romance languages:

- in Asturleones: Carlomagnu;

- in Spanish and Galician: Carlomagno;

- in Catalan: Carlemany;

- in Aragonese: Carlemanyo;

- in French: Charlemagne and Charles le Grand, derivation of old French Charles le Magne;

- in Italian: Carlo Magno and Carlomagno;

- in Portuguese: Carlos Magno;

- in valon: Tchårlumagne and Tchåle li Grand.

Modern variants of Germanic-influenced Slavic dialects are:

- in Croatian: Karlo Veliki;

- in Czech: Karel Veliký;

- in Polish: Karol Wielki;

- in Slovak: Karol Ve dimensionký;

- in Slovenian: Karel Veliki.

The Breton variant is Karl-Veur.

Physical appearance

Although there is no description of Charlemagne as contemporary to the monarch, his biographer Einardo offers a detailed vision of his physical appearance in his work Vita Karoli Magni. In article 22 of the brief he states:

Corpore erat amplo atque robusto, statura eminenti, quae tamen iustam non excederet - nam septem suorum pedum proceritatem eius constat habuisse mensuram -, apice capitis rotundo, oculis praegrandibus ac vegetis, naso paulum mediocritatem excedenti, fait pulcheta Unde formae auctoritas ac dignitas tam stanti quam sedenti plurima adquirebatur; quamquam cervix obesa et brevior venterque proiectior videretur, tamen haec ceterorum membrorum celabat aequalitas. Incessu firmo totaque corporis habitudine virili; voce clara quidem, sed quae minus corporis formae conveniret.He was of a wide and robust body, of eminent stature, without exceeding the just measure, for he reached seven feet of his; of a round head on the top, very great and bright eyes, little more than medium nose, white and beautiful scalpel, joyful and joyful face; so that standing as seated he enhanced his figure with great authority and dignity. And although the cervix was obese and brief and the belly somewhat prominent, it all disappeared before the harmony and proportion of the other members. His walking was firm, and all the attitude of his body, manly; his voice so clear, that he did not respond to the body figure.Eginardo. Vita Karoli MagniXXII.

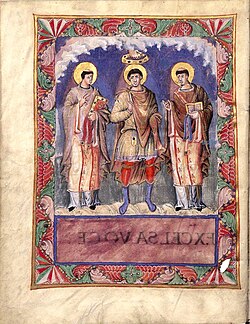

The Carolingian emperor was known among his contemporaries for being a blond, tall, stout man with an excessively thick neck. In his time, the traditional realistic Roman painting technique had been eclipsed by the habit of drawing portraits of personalities surrounded by iconic elements. In his condition of ideal monarch he had to be represented in a corresponding way. At his ascension to the throne he is presented as the incarnation of God on Earth; the paintings of this period contain a considerable number of icons binding to Christ. Modern portraits show a man with a strong complexion and long blond hair, as a result of an error in the interpretation of his biographer's writing; “canitie pulchra” or “beautiful white hair” has been translated as blond or golden mane.

Clothing

Charlemagne wore the traditional, understated, and coarse clothing of the Frankish nation. Eginardo describes it like this:

Patriot Vestitu, id est Francico, utebatur. Ad corpus shirtm lineam, et feminalibus lineis induebatur, deinde tunicam, quae limbo serico ambiebatur, et tibialia; tum fasciolis crura et pedes calciamentis constringebat et ex pellibus lutrinis vel murinis thorace confecto umeros ac pectus hieme muniebat.He dressed the way of the Franks: linen shirt and underwear of the same, tunic with silk handrails; he wrapped his legs with stripes of strips, and in winter he protected shoulders and chest with furs of seal and hammer.Eginardo. Vita Karoli MagniXXIII.

He liked to wear a bluish cloak, as well as a sword, usually finished with a gold or silver hilt. At banquets or ambassadorial receptions she carried imposing jeweled brands. Nevertheless:

Peregrina vero indumenta, quamvis pulcherrima, respuebat nec umquam eis indui patiebatur, except quod Romae semel Hadriano pontifice petente et iterum Leone successore eius supplicante longa tunica et clamide amictus, calceis quoque Romano more formatis induebatur.The strange suits, however beautiful they were, cast them away, so that only once, at the request of the pontiff Adriano, and another at the request of Pope Leo, wore the long robe and the chlamide and used the footwear to the Roman use.Eginardo. Vita Karoli MagniXXIII.

In important festivities he wore a diadem and dressed in embroidered and jeweled garments; on these occasions her cloak included a golden buckle. However, Eginardo affirms that the Frankish monarch despised ostentatious clothing, commonly dressing according to the plebeian fashion.

Rise to power

Early years of life

Charlemagne was the eldest son of Pepin the Short (714-24 September 768, king from 751) and his wife Bertrade of Laon (720-12 July 783), daughter of Caribert of Laon and Gisela of Laon. Among his younger siblings, the records only refer to Carlomán, Gisela and a boy named Pipino who died at a young age. On occasions it has been affirmed that the semi-legendary Redburga, wife of King Egbert of, was Charlemagne's sister —or sister-in-law or niece—, and legends point to him as Roldán's maternal uncle through a lady named Bertha.

Most of what is known about his life comes from the writings of his biographer Eginardo, who wrote the Vita Karoli Magni (or Vita Caroli Magni, 'Life of Charlemagne'). Eginardo affirms about the first years of Carlos' life:

De cuius nativitate atque infantia vel etiam pueritia quia neque scriptis usquam aliquid declaratum est, neque quisquam manera superesse invenitur, qui horum se dicat habere notitiam, scribere ineptum iudicans ad actus et mores ceterasque vitae illius parts explicandaosIt would be nonsense, I think, to write a single word about the birth and childhood of Carlos, or even about his early years, since nothing was written about it and there is no one alive who can give information about it. Consequently, I decided to ignore this and immediately dedicate myself to his person, his works and other facts of his life that deserve to be related and disclosed, and I will refer first to his local and foreign actions, then to his person and activities, and finally to his government and death, without omiting anything that deserves or is necessary to know.Eginardo. Vita Karoli MagniIV.

After Pepin's death, and continuing with tradition, the kingdom of the Franks was divided between Charlemagne and Carloman. Carlos took the outer regions of the kingdom, which bordered the sea, that is, Neustria, western Aquitaine and northern Austrasia; while Carloman had the inland region: southern Austrasia, Septimania, eastern Aquitaine, Burgundy, Provence and Swabia, territories bordering Italy.

Shared Reign

On October 9, immediately after their father's funeral, the two young men left Saint-Denis to be crowned kings by the nobles and anointed by the bishops. Charlemagne's investiture took place at Noyon, while Carloman's was at Soissons.

The first important event that occurred during the joint reign of the brothers was the uprising of the Aquitanians and Gascons, in 769, in the territory divided between both kings. Years before, Pepin had put down the revolt of Gaifier, Duke of Aquitaine. Now a man named Hunaldo—not Duke Hunaldo, it seems—led the Aquitanians north to Angoulême. Charlemagne met with Carloman, but he refused to participate and returned to Burgundy. Charlemagne prepared for war and led an army towards Bordeaux, setting up camp at Fronsac. Hunaldo was forced to flee to the court of Lupo II, Duke of Gascony. Lupo, fearful of Charlemagne, handed over Hunaldo in exchange for peace and he was banished to a monastery. Finally, the Franks completely subdued Aquitaine.

The brothers maintained a lukewarm relationship thanks to the mediation of their mother, Bertrada, but in 770 Charlemagne signed a treaty with Duke Tasilon III of Bavaria and married a Lombard princess, now known as Desiderata, daughter of King Desiderius, in order to surround Carloman with his own allies. Despite Pope Stephen III's initial opposition to his marriage to the Lombard princess, he would soon have little reason to fear a Frankish-Lombard alliance.

Barely a year after their marriage, Charlemagne disowned Desiderata and soon remarried a 13-year-old Swabian named Hildegard of Anglachgau. The disowned Desiderata returned to her father's court in Pavia. With her fury ignited, Desiderio would have gladly allied himself with Carloman to defeat Carlos, but Carloman died on December 5, 771, before the conflict broke out. Carloman's wife, Gerberga, fled with her children to Desiderio's court in search of protection.

Campaign in Italy

The conquest of Lombardy

The year of the appointment as pope of Hadrian I (772), he demanded that control over certain constituent cities of the former Exarchate of Ravenna be restored to him, in exchange for an agreement regarding the succession of desire. Nevertheless, Desiderius took some papal cities and invaded Pentapolis on his way to Rome. In the autumn, Hadrian sent a delegation to Charlemagne, asking him to comply with the policies of his father, Pepin. In turn, Desiderio sent his own embassy denying what the pope accused him of. Both delegations met in Thionville, where the Frankish monarch expressed his support for the papacy. Adriano's demands were joined by those of his ally; Seeing himself in this situation, the Tuscan duke swore that he would never give in. Charlemagne and his uncle Bernard crossed the Alps in 773 and pursued the Lombards until they besieged Pavia. Eventually Charles abandoned the siege in order to deal with Desiderio's son, Adelgis, who was raising an army in Verona. The Franks pursued the young prince to the Adriatic coast. From there Adelgis fled to Constantinople in order to request the help of Constantine V Kopronymos, then at war with Bulgaria.

The siege of Pavia lasted until the spring of 774, when Charlemagne paid a visit to the pope in Rome (2 April); there he confirmed the cessions of territories that his father had stipulated in his will Certain later chronicles, of doubtful veracity, affirm that he expanded them. After Hadrian granted him the title of patrician he returned to Pavia, where the Lombards were on the brink of defeat.

In exchange for their lives, the Lombards surrendered and opened the city gates early in the summer season. Desiderius was sent to Corbie Abbey; his son Adelgis died in Constantinople as a patrician. After having put on the Iron Crown , the Lombard lords —with the exception of Arechis II, who proclaimed the independence of the territories under his control— paid homage to the new monarch in Pavia. By becoming the new king of Lombardy, Charlemagne also became the most powerful lord in Italy. On his departure he left a powerful garrison at Pavia, to which he sent reinforcements every year.

Despite their victory, the Italian territories remained unstable: in 776, the dukes Rodgaudo of Friuli and Hildeprando of Spoleto revolted. Charlemagne hastily moved from Saxony to Italy in order to fight the rebels. He faced Rodgaudo in a battle that resulted in a crushing victory over the rebels and the death of the duke himself. Seeing himself defeated, Hildeprando agreed to sign a peace treaty. His co-conspirator, Arechis, was not subdued and Adelgis, his candidate for his throne, never left Byzantium. Northern Italy had been pacified.

Southern Italy

In 787 Charlemagne turned his attention to Benevento, where Arechis ruled independently; after besieging Salerno, the duke offered vassalage to him. However, when he died in 792, Benevento returned to proclaim its independence under the aegis of his son, Grimoald III. Although the armies of Carlos and his sons attacked him repeatedly, since the Frankish monarch did not return to the Mezzogiorno, these territories would never be subdued.

Carlos and his children

As was the tradition among monarchs and mayordomos of the past, Charles began to appoint his sons to occupy the most important positions in the kingdom during the first period of peace that his government went through (780-782). Having been anointed by the papacy, he made his two youngest sons kings (781): Carloman, the eldest of them, took the Iron Crown and the name "Pipin" on being named king of Italy; and the youngest, Louis, was made king of Aquitaine. Carlos ordered that both be raised in the knowledge of the customs of their kingdoms, while granting their regents some control over said territories. However, although the two young men had the hope of inheriting the kingdom one day, the power was always in the hands of their father. Furthermore, he did not tolerate any insubordination from his sons: in 792 he banished Pepin the Hunchback as a result of a revolt in which he was a party.

Upon coming of age, the monarch's sons fought on his behalf during numerous conflicts. Charles was particularly concerned with the Bretons, with whom he shared a border and who rebelled against him on at least two occasions (although they were easily subdued), and he also fought intensely against the Saxons. In 805-806 he entered the Böhmerwald, modern Bohemia, in order to face the Slavs who inhabited those territories, the modern Czechs. After a quick campaign, he subdued them to the point of forcing them to pay homage to him. After that the Franks devastated the Elbe Valley and imposed tribute in the area. Pepin faced the Avars, as well as the Beneventani and the North Slavs. When a conflict with the Byzantine Empire finally arose as a result of its imperial coronation and the rebellion of Venice, the internal political organization was unbeatable. Luis positioned himself at the head of the Hispanic Brand and, on at least one occasion, headed to southern Italy in order to confront the Duke of Benevento. Carlos's son would take Barcelona after an important siege in 797.

Charlemagne's attitude towards his daughters has been the subject of much controversy; he kept them at home with him and refused to allow them to marry—probably in order to prevent the establishment of sub-branches of the family that might rebel against the main one, as was the case with Tasilon III of Bavaria—although he allowed them to have extramarital affairs, even going so far as to honor his concubines, and he had great appreciation for the bastard children they fathered. Apparently he never believed the stories that circulated around his savagery. After Charlemagne's death, her son Louis banished them from court and sent them to convents that her father had chosen. One of them, Bertha, had a relationship, or perhaps a marriage, with Angilberto, a member of her father's court.

Campaign in the Iberian Peninsula

The Roncesvalles campaign

According to the Muslim historian Ibn al-Athir, the Diet of Paderborn received in 777 the representatives of the Muslim rulers of Zaragoza, Gerona, Barcelona and Huesca, who had come there because their lords had been cornered on the peninsula Iberian by Abderramán I, the emir of Córdoba. These Muslim or Saracen rulers offered homage to the great king of the Franks in exchange for his military aid. Charlemagne, seeing an opportunity to extend both Christianity and his own power and believing the Saxons to be a subjugated nation, agreed to head for the Iberian peninsula.

In 778, he led the army of Neustria across the Western Pyrenees, while the Austrasians, Lombards, and Burgundians crossed the Eastern Pyrenees. The armies met in Zaragoza and received the homage of Sulayman al-Arabí and Kasmin ibn Yusuf, the foreign rulers. However, Zaragoza did not fall as quickly as Charlemagne thought; he even found himself facing the most difficult battle he had faced in his entire career and, fearing defeat, he decided to retire and return home. Charlemagne could not trust the Muslims or the Basques, whom he had faced during his conquest of Pamplona, and he was leaving the peninsula through the Roncesvalles Pass when one of the most famous events of his entire reign occurred: The Basques fell on their rear guard and cargo wagons, destroying them. The battle of Roncesvalles left several famous dead, including the seneschal Eggihard, the count of the Anselmo palace and the prefect of the Marca de Brittany, Roldán, later inspiration for the Cantar de Roldán (Chanson de Roland), the famous French epic song.

Since ancient times, there was a legend in Toledo about the alleged love affairs between Charlemagne and Princess Galiana, which served as the plot of a 12th-century French poem entitled Mainet, which, according to Menéndez Pidal, was written in Toledo by the "minstrel of Mainet", supposedly one of the Franks living in the city, especially in the "arrabal de los francos".

The war against al-Andalus

The conquest of Italy brought Charlemagne into contact with the Saracens who, at that time, controlled the Mediterranean and arduously occupied his son Pepin. Charlemagne conquered Corsica and Sardinia at unknown dates, and the Balearic Islands in 799. These islands were frequent targets of attacks by Saracen pirates, but the Count of Genoa and Tuscany (Boniface) kept them at bay by sending a large fleet. whose operation lasted until the end of the reign of Charlemagne. The king came to have contact with the caliph's court in Baghdad: in 797 (or possibly 801), the caliph of Baghdad, Haroun al-Rashid, presented Charlemagne with an Asiatic elephant named Abul-Abbas and a watch. As a background situation, the rapprochement with the Abbasid caliphate was due to the common enmity against the Byzantines.

In Hispania, the struggle against the Muslims continued unabated throughout the second half of Charlemagne's reign. In 785, the soldiers of his son Luis, who was in charge of defending the border with Spain, permanently conquered Gerona and extended Frankish control to the Catalan coast; such control was maintained for the remainder of Charlemagne's rule (and even remained nominally Frankish long after, until the Treaty of Corbeil in 1258). The Muslim warlords of north-eastern Islamic Spain continually revolted against the Cordovan authorities and often called on the help of the Franks, whose border continued to slowly expand until 795, when Gerona, Cerdanya, Osona and Urgell were grouped into the new Hispanic Brand, within the old Duchy of Septimania.

In 797 Barcelona, the main city of the region, fell to the Franks when Zeid, its governor, rebelled against Córdoba and, after failing, turned it over to Charlemagne. Despite the fact that the Umayyad authorities managed to recapture it in 799, Luis marched with his entire army, crossed the Pyrenees and besieged the city for two years, spending the winter there from 800 to 801, until his surrender. The Franks continued to attack the emir: in 809 they occupied Tarragona and, in 811, Tortosa. This last conquest took them to the mouth of the Ebro and allowed them access to Valencia, which prompted the emir Alhakén I to recognize his conquests in 812.

Campaigns in Eastern Europe

War against the Saxons

Charlemagne was involved in constant battles throughout his reign, often at the head of his elite squadrons or caras and with his legendary sword, Joyeuse, in hand. After thirty years of war, he managed to conquer Saxony and proceeded to convert it to Christianity, using force whenever necessary. At the end of the 8th century the Carolingian army of about 100,000 men on campaign, this included a large number of temporarily recruited troops from various regions and tribes, about 10,000 full-time professional soldiers, about 6,000 mounted knights, and a similar number of mercenaries.

The Saxons were divided into four groups, according to their regions of belonging: Westphalia, which bordered on the west with Austrasia and, beyond, Estfalia. In the middle of these two kingdoms was that of Angria, and north of the previous Nordalbingia, at the base of the Jutland peninsula.

During his first campaign, Charlemagne defeated the Saxons at Paderborn and forced the Angrians to cut down and surrender an irminsul (a sacred wooden pillar) found in 772 near Paderborn. The campaign was interrupted by his first expedition to Italy in 774, with the rebellion still active. When he returned the following year (775), he traversed Westphalia and conquered the Saxon fort of Sigiburg. Next, he crossed Angria, where he again defeated the Saxons. Finally, in Eastphalia, he defeated a Saxon detachment and converted their leader, Hessi, to Christianity. On his way back through Westphalia, he set up camps at Sigiburg and Eresburg, hitherto important Saxon strongholds. All Saxony was under his rule, with the exception of Nordalbingia; however, the Saxon resistance was not over.

After his campaign in Italy subjugating the dukes of Friuli and Spoleto (Rodgaudo and Hildeprando, respectively), Charlemagne rushed back to Saxony in 776, as a revolt had destroyed his fortress at Eresburg. Once again the Saxons were crushed, but his most important leader, Duke Widukind, managed to escape to Denmark, the home of his wife. Charlemagne built a new camp at Karlstadt and, in 777, called a national diet at Paderborn to complete the integration of Saxony into the Frankish kingdom. Faithfully following his religious policy, he had a considerable number of Saxons baptized.

In the summer of 779, he again invaded Saxony and recaptured Eastphalia, Angria, and Westphalia (lost in the rebellion the previous year). In a diet held near Lippe, he divided the territory into different missions and attended several mass baptisms in person (780). He then returned to Italy and, for the first time, there was no immediate Saxon revolt. In 780 Charlemagne decreed the death penalty for those Saxons who did not get baptized, did not celebrate Christian holidays and cremated their dead. Between 780 and 782, Saxony experienced a period of peace.

Charlemagne returned to Saxony again in 782. He established a code of laws and appointed several counts, both Saxon and Frankish. The laws were severe in religious matters, and the autochthonous German polytheism was left in an extremely precarious condition with respect to Christianity, which aroused old conflicts. That same year, Widukind returned in the autumn to lead a new revolt, which resulted in several attacks on the Church. In response, Charlemagne is believed to have ordered in Verden, Lower Saxony, the beheading of 4,500 Saxons who had been caught practicing their native paganism after converting to Christianity. The event, known as the Verden Massacre, sparked two years of bloody conflicts (783-785) that meant the forced transfer of about 30,000 Saxons to other regions of the empire. During this war, the Frankish king won the battles of Lippspringe (782) and Delmont (783) and finally managed to subdue the the Frisians and set a large part of their fleet on fire. The war ended when Widukind agreed to be baptized in 804.

After this event, the Saxons remained at peace for seven years, until the Westphalians rebelled again against their conquerors. Eastphalia and Nordalbingia joined them in 793, but the uprising did not enjoy the support of the entire population and was put down around 794. A revolt in Angria followed in 796, though it was quickly put down by the presence of the Christian Saxons, the Slavs and Charlemagne himself. The last attempt at independence occurred in 804, more than thirty years after Charlemagne's first campaign in Saxony. On this most turbulent occasion of all, the people of Nordalbingia found themselves unable to lead a new rebellion. According to Einardo:

The war that had lasted so many years ended at last when they agreed to the terms offered by the king, which consisted of relinquishing their national religious customs and worshiping demons, accepting the sacraments of religion and Christian faith, and joining the Franks to form a single people.

Pagan resistance in Saxony had ended. To make sure of this Charlemagne ordered the forced removal of 10,000 Saxon families and the handing over of their lands to the loyal Abrodites.

Submission of Bavaria

In 788, Charlemagne turned his attention to Bavaria and accused Tasilon of making deals with the Avars and other enemies of his, thereby breaking his promise of allegiance. Put on trial, Tasilón was deposed and sentenced to death, but Charles pardoned him and contented himself with having him shaved and imprisoned in the monastery of Jumièges. Finally, in 794 Tasilón was forced to renounce his rights and those of his family (the agilolfingos) over Bavaria, at the Frankfurt synod. Bavaria, like Saxony, was subdivided into counties by the Franks.

Campaign against the Avars

The wars of the Franks against the Avars were a series of war campaigns led by the Franks in the Danube against the Avars of Panonia from 791 to 805, which resulted in the submission of the Avar kanato.

The Avaros, a pagan people of looters who had settled in the sixth century, in the plains of the present Hungary, were a constant threat to the Franks. They multiplied the devastating raids in Bavaria and Friuli (788), then submitted to Carlomagno, who decided to launch an expedition against them in 791.For the next two years, Charles was busy with both the Slavs and the Saxons. However, Pepin and Duke Eric of Friuli continued their attacks on the circular fortresses of the Avars. The great "Ring of the Avars", their most important fortress, was taken twice. The collected loot was sent to Charlemagne, who was in his capital, Aachen, and redistributed it among his followers and foreign rulers, including King Offa of Mercia. Before long, the Avar tuduns gave up and traveled to Aachen to submit to Charlemagne as vassals and Christians. Carlos agreed, and one of the native chiefs, who had been baptized Abraham, was sent back under the old title of jaghan. Abraham maintained discipline among his people, but by the year 800 the Bulgars under Krum had completely wiped out the Avar state. In the X century the Magyars would establish themselves on the Pannonian plain, presenting a new threat to the descendants of Charlemagne.

Expeditions against the Slavs

The territorial expansion that the Carolingian Empire experienced until 789 led it to make contact with new pagan neighbors, the Slavs. Charlemagne led an army made up of soldiers from Austrasia and Saxony, with which he crossed the Elbe and entered Abrodite lands. The Slavs led by Witzin immediately surrendered. Subsequently, Carlos accepted the submission of the Veleti, ruled by Dragovit, demanding hostages and permission to send, without interference, missionaries to the region. The army reached the Baltic region before retracing its steps and heading towards the Rhine with the loot obtained and without suffering harassment. The Slavic tributary state became a loyal ally. In 795, when peace with the Saxons broke down, both Obodrites and Veleti took up arms to join their new master against the rebels. Witzin died in combat and Charlemagne avenged him by ravaging the Elbe region corresponding to Estfalia. Thrasuco, Witzin's successor, led his men in the conquest of Nordalbingia and turned the rebel leaders over to Charlemagne, earning him great honors. The Obodrites remained loyal to Charles until his death, and then they fought against the Danes.

Charlemagne also turned his attention to the South Slavs of the Avar Khaganate: the Carantanians and the Slovenes. These towns were subdued by the Lombards and the Bavarians, and turned into tributaries, although they were never incorporated into the Frankish state.

Empire

Imperial Diplomacy

After these events the day of the feast of the Birth of our Lord Jesus Christ met again in the sad Basilica of St Peter the Apostle. Then the venerable and benevolent prelate crowned him with his own hands with a magnificent crown. Then all the faithful saw the protection so great and the love that had the Holy Mother Roman Church and her vicar unanimously shouted in a loud voice, with the pleasure of God and the blessed Saint Peter, the porter of the heavenly kingdom: To Charlemagne, pious august, by God crowned, great and peaceful emperor, life and victory!Liber Pontificalis, XCVIII-23-24

Charlemagne's reign came to a head in the late 800s. In 799, Pope Leo III had been attacked by the Romans, who attempted to gouge out his eyes and tongue. Leo escaped and took refuge with Charlemagne in Paderborn, asking him to intervene in Rome and restore his rule. The Frankish king, advised by Alcuin of York, agreed to travel to Rome and did so in November 800. On December 1 he held an assembly and, on the 23rd of the same month, Leo took an oath declaring himself innocent. During the mass celebrated on Christmas (December 25), when Charlemagne knelt to pray before the altar, the pope crowned him Imperator Romanorum ('emperor of the Romans') in the basilica of Saint Peter. With this act, the Pope tried to transfer to Carlos the position of Constantinople. Einardo points out that Charlemagne was unaware of Leo's intentions and did not want such an appointment:

At the beginning was such an aversion, which declared that he had not set foot in the Church on the day that he was conferred [the imperial titles], although it was a great holiday, that he might have foreseen the designs of the pope.

Many modern scholars suggest that Charlemagne was actually aware of the coronation plans. Certainly, as he approached to pray, he could not have failed to notice the jeweled crown that he awaited on the altar. In any case, he could now take advantage of the circumstances to claim that he was the restorer of the Roman Empire, which had apparently degraded under Byzantine rule. However, after 806, Charles would go on to designate himself not as Imperator Romanorum ('emperor of the Romans', a title reserved for the Byzantine emperor), but as Imperator Romanum gubernans Imperium ('ruling emperor of the Roman Empire').

The iconoclasm of the Isaurian dynasty and the consequent religious conflicts with Empress Irene, who in the year 800 occupied the throne of Constantinople, were probably the main reasons why the pope wanted to formally acclaim Charles as Roman emperor. In addition, he also wanted to increase the influence of the papacy, honor its savior—Charlemagne—and resolve the constitutional questions that were currently afflicting European jurists, at a time when Rome was not in the hands of an emperor. Thus, when Charlemagne assumed the title of emperor, in the eyes of the Franks and Italians it was not a question of a usurpation of office; but it was in Constantinople, where Irene and her successor, Nicephorus I, protested vigorously without either of them achieving anything about it.

However, the Byzantines continued to hold several territories in Italy: Venice (what was left of the Exarchate of Ravenna), Reggio (in Calabria), Brindisi (in Apulia) and Naples (the Neapolitan Duchy). These regions remained outside Frankish rule until 804, when the Venetians, torn by infighting, transferred their allegiance to the Iron Crown of Charles's son Pepin. The Pax Nicephori ended and Nicephorus ravaged the coasts with a fleet and thus began the only war between the Byzantines and the Franks. The fighting lasted until 810, when the pro-Byzantine side in Venice once again conferred control of the city on the Byzantine Empire and the two emperors of Europe made peace: Charlemagne received the Istrian peninsula, and in 812 Emperor Michael I Rangabé recognized his status as emperor.

The Danish Attacks

After the conquest of Nordalbingia, Frankish territory bordered Scandinavia. The Danish heathens, “a race almost unknown to their ancestors; [from Charles]. But destined to be widely known by her children' as described by Charles Oman, who inhabited the Jutland peninsula had heard many of the stories related by Widukind and his allies, who took refuge at the Danish court, as well as of the ferocity with that the Christian king treated his pagan neighbors.

In 808, the Danish king, Geoffrey, built the great Danevirke along the isthmus of Schleswig. Originally 30 km long, this defensive wall was last used during the War of the Duchies in 1864. The Danevirke was intended to protect the Danes, while at the same time it provided Godfrey with the opportunity to plunder Friesland and Flanders by means of pirate raids. In addition, the Dane subdued the Veleti, allies of the Franks, and fought the Obodrites.

Godfrey invaded Friesland and joked about visiting Aachen. However, he could not do otherwise as he was killed, although whether at the hands of an outspoken assassin or one of his own men is unknown. Godfrey was succeeded by his nephew Hemming, who signed the Treaty of Heiligen with Charlemagne in late 811.

Death

In 813, Charlemagne summoned Ludovico Pius, King of Aquitaine and his only surviving son, to his court. Once there, he crowned him co-emperor with his own hands and then sent him back to Aquitaine. He then spent the autumn hunting before returning to Aachen on 1 November. In January 814, he fell ill with pleurisy (Eginard 59) and on the 21st he fell into a coma. Eginardo tells that:

He died on the twenty-eighth of January, the seventh day since he fell in bed, at nine o'clock in the morning, after participating in the Eucharist, in his seventy-second year of life and the forty-seventh of his reign.

Carlos was buried the same day he died in Aachen Cathedral, although the cold weather and the nature of his illness did not impose any haste on his burial. A later account, narrated by Oto de Lomello, count of the palace of Aachen in the time of Otto III, would indicate that he and the emperor Otto had discovered the tomb of Charlemagne; these two men seated the emperor on a throne, clothed him with a celebratory crown and scepter, and covered his uncorrupted body in ostentatious robes. In 1165, Emperor Frederick I reopened the tomb and transferred the body to a sarcophagus that he placed under the floor of the cathedral. In 1215, Frederick II would place it again in a gold and silver coffin.

The death of Charlemagne deeply affected many of his courtiers, especially those who formed a kind of "literary clique" attached to the emperor in Aachen. This is how an anonymous monk from Bobbio laments:

From the lands where the sun rises to the western beaches, people weep and weep... the Franks, the Romans and all Christians are hurt with great concern... young and old, glorious nobles, all mourn the loss of their Caesar... the world mourns the death of Charles... Christ, you who rule the heavens, grant Charles a quiet place in your kingdom. For my misfortune.

He was succeeded by his surviving son, Ludovico, who had been crowned the previous year. His empire remained intact for a single generation more; Historiography affirms that the effective division between the children of Ludovico gave rise to the formation of the modern states of France and Germany.

Administration

Charlemagne stands out as an administrator thanks to the numerous reforms that were carried out during his reign: economic, governmental, military, cultural and ecclesiastical. He constitutes the protagonist of the « Carolingian Renaissance».

Economic and monetary reforms

Charlemagne played an important role in laying the foundations for Europe's economic future. Following his father's reforms, he abolished the gold-based monetary system sou and, together with the Anglo-Saxon king Offa of Mercia, promoted the system that Pepin had put in place. At that time there were pragmatic reasons for making this decision, mainly the scarcity of gold itself, a consequence of the peace treaty that had been signed with Byzantium, the cession of Venice and Sicily, and the end of trade relations with Africa and the East.

A new currency began to circulate, the Carolingian pound (whose name derives from the Roman pound, the modern pound), based on a pound of silver, a unit both monetary and peso, equivalent to 20 sous (from the Latin solidus, which was used mainly in accounting records but was never minted, and from which the modern shilling is derived) or 240 deniers (from the Latin denarius, the modern penny). During this period, the livre and the sou were units of account, while only the denier was actual currency.

Charlemagne instituted the principles of accounting by means of the capitulare de villis (802), a document that establishes a series of norms by which all public income and expenses had to be registered.

In turn, with an effort to gain greater control over the kingdom, Charlemagne limited the power over the counts, demanding, among other things, that they provide services outside their family properties and that they were periodically changed places instead of residing for life in a single county, it also established that the positions were held by appointment, preventing the children of the counts, often inefficient for the tasks of management and control of the territory, automatically inheriting the positions of their parents. Meanwhile, in order not to submit knowledge of the state of their territories solely to the vision or stories of their counts, they established the system of missi dominici, the "messengers of the Lord King", being these two men — one lay and the other ecclesiastical —, sent to each region in order to monitor the execution of the king's wishes.

Usury was outlawed, which was reinforced in 814, when the Capitulare de los jews was introduced, prohibiting Jews from lending money.

In addition to these macroeconomic practices, the Frankish monarch carried out an important number of microeconomic exercises, such as direct control over prices or special taxes on certain goods and basic products.

Charlemagne applied this system to much of the European continent; In parallel, Offa's system was voluntarily adopted in England. Following the death of the Frankish monarch, the European currency suffered a major degradation, causing most of Europe to adopt the use of British currency until c. 1100.

Educational reforms

Much of Charlemagne's success as a military man and administrator can be attributed to his admiration for learning. Because of the renaissance of teaching, literature, art and architecture that characterizes them, certain historians refer to his reign and his time under the name of the Carolingian Renaissance. Charlemagne came into contact with the culture and education present in other countries, especially in Visigothic Spain, Anglo-Saxon England and Lombard Italy, thanks to his conquests. During his reign the monastic schools and scriptories existing in France multiplied. Carolingian scholars copied and preserved many of the surviving Latin classics. In fact, the earliest available manuscripts of ancient texts originate from this time: almost all of the texts that survived up to his reign survive today. Many men who worked for the emperor indicate the existence of the pan-European character that had Carolingian influence: Alcuin, an Anglo-Saxon from York; Theodulf, a Visigoth from Septimania; Paul the Deacon, Lombard; Pedro de Pisa and Paulino de Aquilea, Italians; and Angilberto, Angilramm, Eginardo and Waldo de Reichenau, Franks.

Charlemagne took a serious interest in scholarship and the promotion of the liberal arts at court. He ordered that all his descendants be well educated. He himself studied grammar with Paul the deacon; rhetoric, diction and astronomy with Alcuin, and arithmetic with Eginardo. The latter mentions Charlemagne's only academic failure, not knowing how to write: he tried to learn in his old age by practicing the formation of letters in books and wax tablets that he hid under his pillow in his spare time in his bed, «his efforts reached too late and bore little fruit." His ability to read from him has been questioned, since Eginardo does not refer to it at any time, nor is it endorsed by any contemporary source.

Cultural reforms

During the reign of Charlemagne, the Roman capital letter and its cursive form, which had given rise to various lower case letters, were combined with certain typefaces used in English and Irish monasteries. The Carolingian minuscule was created from this combination during the reign of the homonymous emperor. It is probable that he participated in the conception of Alcuin of York, a man who worked in the palace school and in the scriptorium of Aachen. Despite this, the revolutionary character of the Carolingian reform could have been overestimated; efforts to master the intricate Merovingian and Germanic calligraphy were already present before Alcuin arrived in Aachen. The new minuscule was spread first from Aachen, and later from the influential scriptorium of Tours, where Alcuin became abbot.

Political reforms

Charlemagne made numerous reforms that were unprecedented among his predecessors on the Frankish throne; however, he chose to continue with many traditional practices, such as the division of the kingdom among the sons.

Organization

The Carolingian king exercised the bannum, the right to reign and command. He enjoyed the supreme jurisprudence in judicial matters, legislated, led the army, and had the duty to defend the Church and the disadvantaged. His administration carried out an attempt to organize and adhere to the kingdom the church and the nobility; however, the kingdom was dependent on the efficiency and loyalty of both orders.

Regarding the dangerous border regions, he established a system of officials known as margraves, a term that came from mark graf, count of border district or mark, although the counts were titles of nobility already existing in the Merovingian reign.

While we can point to many of Charlemagne's organizational and economic reforms, argues historian Jackson Spielvogel, we should not imagine an efficient functioning of the governmental system, since officials had to cover great distances on horseback, making Charlemagne's true control impossible. and their partners on local issues. The cohesion of the empire was simply maintained by personal loyalty to the king, often fueled by fear of military strength and coercion.

Imperial Coronation

Historians have long debated whether Charlemagne was aware that the pope intended to crown him emperor before the appointment took effect. However, this debate has overshadowed a much more important one: for what reason This title was granted to the Frankish monarch, and for what reason he accepted it.

Roger Collins points out that "the reasons for accepting the imperial title as the result of an ancient romantic interest in reviving the Roman Empire are highly unlikely". On the one hand, such a romantic aspect would not have attracted attention even from the Franks or the Catholics of the early IX century, since they distrusted the classical heritage. The Franks boasted of having "fought and shaken off the heavy Roman yoke" and of the "knowledge obtained through baptism, adorning in gold and precious stones the bodies of the holy martyrs whom the Romans had killed with fire, swords and wild animals", as Pepin described it in a law issued in 763 or 764. In addition, the new title carried the risk that the emperor "introduced drastic changes in the traditional forms and procedures of government" or "focused his attention on matters of Italy or the Mediterranean more frequently", which threatened to alienate the Frankish leader.

For both the pope and Charlemagne, the Roman Empire was still a major power in European politics at the time, still holding a considerable part of Italy's territory, with borders not far from the city of Rome itself.. It is about the empire that historiography has called the Byzantine Empire, since its capital was Constantinople —the old Byzantium— and whose people, rulers and customs gradually returned to their Greek roots. Certainly, Charlemagne was usurping the prerogatives of the Roman Emperor in Constantinople, first of all, with the simple act of being able to judge the pope:

By whom, however, could he [the pope] be judged? Who, in other words, was qualified to render a judgment about the Vicar of Christ? In normal circumstances the only possible answer to this question would be the emperor of Constantinople, but at that time Irene occupied the imperial throne. That the empress was famous for having blinded and killed his own son was something, for Leon and Carlos, irrelevant: it was simply a woman. Both believed that the female sex was incapable of governing, and the sadistic tradition prevented it from happening. As far as Western Europe was concerned, the Byzantine throne was empty: Irene was only a test, if anything else was needed, of the envilence in which the Roman Empire had fallen.John Julius Norwich Byzantium: The Early Centuries, p. 378

For this reason, for the pope "there was no emperor on the Byzantine throne at that time". at that time a woman was reigning in Constantinople". Since 727, the papacy had maintained a tense relationship with Irene's predecessors on the throne of Constantinople. This diplomatic tension had been caused by the Byzantines' adherence to iconoclastic culture and the destruction of Christian images. By 750, the secular power of the Byzantine Empire in Central Italy had been neutralized. By granting the imperial crown to Charlemagne, the pope arrogated to himself "the right to name the emperor of the Romans, making the imperial crown a personal gift from him, and at the same time implicitly conceding to himself a certain superiority over an emperor." whom he himself had created." In addition, "the Byzantines had shown themselves incapable of honoring their military, doctrinal and political position, for which reason the Pope was obliged to replace them with a Western monarch: a man who, due to his wisdom, his political capacity and his power, territorial stand out above his contemporaries.

With Charlemagne's coronation "the unity of the Roman Empire was maintained, and both [Charlemagne and Leo] had the responsibility of maintaining its cohesion, with Charles as its emperor." Although the possibility existed that "the coronation, with all that it implied, would be angrily rejected in Constantinople". Looking at the circumstances of Charles's appointment from a realistic point of view, the pope and Charlemagne himself must have realized that there were little chance that the Byzantines would accept the monarch of the Franks as their emperor. Alcuin speaks hopefully in his letters of an Imperium Christianum ('Christian Empire') in which, "just as in the Roman Empire, the inhabitants were united by a common citizenship." ». Likewise, the responsibility of maintaining an imperial unity would fall on the Christian faith. Pirenne shares this point of view when he affirms that "Charles was the emperor of the ecclesia conceived by the papacy, of the Roman Church, recognized as the universal Church."

Regardless, according to the writings of the chronicler Theophanes, Charlemagne's first reaction after his coronation was to send an embassy to Irene through which he proposed marriage. Unexpectedly, the reaction of the basilissa was favorable to this marriage, since she would help her to consolidate her throne. Only the Byzantines' rejection of this union and the conception of a conspiracy aimed at overthrowing Irene and appointing Nicephorus emperor—which would eventually happen—made Charlemagne abandon the wedding plans. Following this failure, Charlemagne reduced the scope of his title to a minimum and had the people address him as "Rex francorum et langobardum" ("King of the Franks and Lombards").

The title of emperor remained in his family throughout his reign and that of his son, being abandoned after the conflict that confronted the descendants of Luis to achieve the supremacy of the Frankish State. However, the papacy did not forget the title or renounce its right to grant it. When the Carolingian dynasty ceased to produce heirs deemed "worthy," the pope chose to crown any Italian leader capable of protecting him from his enemies. The arbitrariness that characterized the granting of the title opened the door —as was to be expected— to its disappearance for almost forty years (924-962). Finally, in the Rome of a Europe radically different from that of Charlemagne, the pope re-crowned (962) a "Roman emperor." This new emperor, Otto the Great, linked this title to the German monarchs for almost a millennium, since historiography considers him the first representative of the Holy Roman Empire. Otto was the successor of Charlemagne, and therefore, the successor of Augustus.

Divisio regnorum

In 806, Charlemagne made the first plans to divide his Empire upon his death. Charles the Younger would have bequeathed Austrasia, Neustria, Saxony, Burgundy, and Thuringia; Pepin Italy, Bavaria and Swabia; to Luis Aquitania, the Hispanic Brand and Provence. There is no mention of the imperial titles, however, certain historians have affirmed that the Frankish monarch considered the titles as a reward that each one had to earn, and not as an inheritance.

This division could have been effective, but the deaths of Pepin (810) and Charles (811) forced Charlemagne to reconsider the division. In 813 he gave Louis the opportunity to reign with him until his death, by crowning him and naming him co-emperor and co-roy of the Franks. The only part of the Empire that he did not concede to his heir was Italy, promised years ago to Pepin, Bernard's illegitimate son.

Relations of Charlemagne with the Church and the Papacy

Charlemagne continued his father Pepin the Short's policy of alliance and defense of the Papacy. In the case of Charlemagne, to the political reasons for this was added his authentic conviction about the benefits of a Christian Empire in which the emperor and the pope collaborated mutually. Still young and somewhat inexperienced in his relations with Pope Adrian I, with his successor Leo III Charlemagne naturally established the supremacy of the emperor over the pope.

In the case of Hadrian I, Charlemagne held him up against the Lombards. It should be noted that the relations between Charlemagne and Adriano I were always good and mutually beneficial because they were two outstanding personalities whose purposes, deep down, were complementary and they knew how to recognize it.

We must emphasize that the relationship between the pope and the emperor contributed to greatly increase the prestige of the Papacy. Indeed, this relationship was key to enormously accelerating the slow process – it lasted centuries – that gradually converted the pope from his original role as bishop of Rome to almost equal status with the bishops of other important dioceses and even inferior to the Patriarch of Constantinople, head of Christendom.

On the death of Hadrian I, his successor, Leo III, faced a rebellion by the aristocratic families of Rome and was deposed. He appealed to Charlemagne, who appeared in Rome with an army and presided over a synod in which he acted as the pope's judge, since his detractors accused Leo III of adultery and perjury. The synod upheld Leo III's oath that he was innocent of the charges and acquitted him, returning him the pontifical tiara.

The important thing about this fact beyond the anecdotal is its symbology: Charlemagne acted as the pope's judge. With this, he established the supremacy of the emperor. However, upon receiving the crown of the Empire from the hands of the Pontiff —Eginhardo later stated that Charlemagne would not have attended Saint Peter's Basilica that day if he had known what Leo III was proposing to do; it is obvious that Charlemagne agreed with his coronation as emperor but perhaps would have objected that it was the pope and not he himself who placed the crown on his head—a dangerous precedent was generated that would later have catastrophic consequences for the imperial dignity, delivered as it was made petty by a series of weak and corrupt popes, until Otto I rescued it under the name of the Holy Roman Empire from the ignominy into which it had fallen.

Causes for the rapid disintegration of the Empire after his death

Despite his efforts and determination, Charlemagne failed to endow his Empire with a political organization that could subsist on its own against the threats that hung over it. The entire organization of the Empire rested on a necessary condition: the fidelity of the nobles to the emperor and king of the Franks and the Lombards. All this in an economic and social context in which the counties became more and more autonomous: in principle, as it was very expensive to keep a warrior on horseback with all his equipment, only the large owners could afford it and the remaining free men could not. they had no alternative but to entrust themselves to a lord as vassals. It should be noted that there was no permanent army in the Kingdom of the Franks, but rather arms levies were carried out and each warrior had to equip himself on his account. They lived in a rural society whose economy was subsistence agriculture, the population of the cities had diminished and was reduced to its minimum expression, while Western trade had practically disappeared after the domination of the Mediterranean by the Arabs. The bourgeoisie had not yet emerged as a social class and the provinces had to subsist on their own resources.

Thus, between the emperor and the free men, the intermediary caste of nobles to whom their vassals had to respond grew increasingly stronger. It was only a matter of time that in such an extensive Empire in which communications were so scarce and deficient, the vassals responded more to their local lords than to the emperor. As long as Charlemagne lived, his extraordinary prestige, his steady hand, and his iron will made him obeyed over the impending disintegration. Only if his successor had been a king with the talents of Charlemagne would the Empire have had a chance of survival. But his son Charles, who had great military talent and to whom Charlemagne had entrusted some of his most difficult missions, did not survive him.

Already during Charlemagne's lifetime, an event had taken place that marked the weakening of the fidelity on the basis of which the skeleton of the Empire was erected. In the summer of 807 very few of the lords and warriors summoned to the annual assembly showed up and, for the first time, the assembly could not be held. It was an unprecedented event. Charlemagne interpreted it as a rebellion against his authority, sent his missi to investigate each county and punished this growing desertion with edicts.

With the death of Charlemagne and given the dim insights of his son and successor Luis the Pious, events precipitated. The civil wars between the monarch and his sons ended the prestige of the emperor. The magical fidelity that at that point was only maintained by the extraordinary figure of Charlemagne disappeared and the Empire, already mortally wounded, ended up being shipwrecked thanks to the exacerbation of the Nordic attacks, giving way to the full height of feudalism.

The Empire was unfeasible given the economic, political and social conditions of the time and only the figure of Charlemagne had been able to sustain it. His successors were to suffer the same fate that their ancestors had lavished on the last Merovingian kings: first the loss of effective power, which in this case was transferred to the great feudal lords, and finally the loss of the throne, which passed to Germany. to the house of Saxony – paradoxically, the country that Charlemagne had conquered – and in France to the Capetians.

In the year 843, after the death of Louis the Pious, the three surviving brothers Charles the Bald, Louis the Germanic, and Lothair celebrated a treaty in the city of Verdun, by which they divided the possessions that had belonged to their grandfather Charles the Great, namely: Charles the Bald (843-877) obtained the free lands to the west, which formed the core of what would later become France; Louis the German (843-876) seized the lands to the east, which would be the seedbed of later Germany, and Lothair (840-855) was given the title of a "Middle Kingdom" which stretched from the North Sea to Italy, and included the Netherlands, the lands adjacent to the Rhine, and northern Italy.

Cultural Impact

The name and figure of Charlemagne are and have been timeless. The author of Visio Karoli Magni —written around 865— uses excerpts from Aeginard's work and data obtained from his own observations about the decline of Charlemagne's family after internal dissensions that led to a civil war (840-843) as the basis for writing about a vision in which the spirit of Charles appeared to him.

Charlemagne—who became a model gentleman as a member of the Nine of Fame—had a profound impact on European culture. The Matter of France, one of the most important medieval literary cycles, has Charlemagne as one of its central characters. In addition, the famous Song of Roldán narrates the battle of Roncesvalles, in which the famous Roldán and the French paladins fought similar to the Knights of the Round Table of King Arthur's court. These tales constitute the first cantar de gesta in history.

In the 12th century his sanctity was recognized within the borders of the Holy Roman Empire. His canonization — officiated by Antipope Pascual III in order to obtain the favor of Frederick Barbarossa (1165) — was not recognized by the Holy See, which annulled all of Pascual's ordinances after the Third Lateran Council (1179).. However, his beatification would finally be confirmed.

It has been claimed that Charlemagne supported the insertion of the Filioque into the Nicene Creed. The Franks had inherited the Visigothic belief that the Holy Spirit proceeded from God the Father and the Son (Filioque); and during the reign of Charlemagne, the Franks ignored what was stipulated in the Council of Constantinople and declared that the Holy Spirit only proceeded from the Father. Pope Leo III opposed this belief and had the Nicene Creed carved on the doors of St. Peter's Basilica without the offending phrase. The insistence of the Franks led to a decline in relations between Rome and France. However, the Catholic Church ended up adopting this phrase, this time antagonizing Constantinople. This fact is considered as one of the many precursors of the Eastern Schism, which happened centuries later.

In the Divine Comedy his spirit appears to Dante in the «sky of Mars» accompanied by other «soldiers of faith».

According to the popular etymology, the Chariot of the constellation Ursa Major received the name «Carro de Carlos» (Charles's Wain) in honor of Charlemagne.

French volunteers from the Wehrmacht and later Waffen-SS were organized during World War II into a unit called the 33rd Charlemagne Volunteer SS Grenadier Division. A German unit of the Waffen-SS used the name "Karl der Große" during 1943, but ended up being called 10th SS Panzer Division Frundsberg.

Since 1949, the city of Aachen has been awarding an international prize called Karlspreis der Stadt Aachen in his honor. It is awarded annually to "men of merit who have promoted the idea of Western unity through their political, economic and literary efforts". Laureates include Count Richard Coudenhove-Kalergi, founder of the pan-European movement, Alcide De Gasperi, and Winston Churchill.

The British weekly publication The Economist, focused on international news, dedicates an article called "Charlemagne" to a European government leader.

Family

Marriages and heirs

Charlemagne fathered twenty children with eight of his ten known wives or concubines.

- With Himiltruda he maintained his first relationship, whose nature is often described as a concubine, a legal marriage or a friedelehe. Two children were born from this union:

- Amaudru, a girl.

- Pipino el Jorobado (c. 769-811)

- Carlomagno separated from Himiltrude when he married Desiderata, daughter of the king of the Lombards Desiderio in 770; annulled marriage in 771,

- Then he married Hildegarda (757 or 758-783). The marriage, held in 771, ended with the death of the marriage (783). Nine children were born from this marriage:

- Carlos el Joven (c. 772-4 December 811), Duke of Maine crowned King of the Franks on December 25, 800.

- Pipino de Italia (773-8 July 810). Its trastataranieto will be Hugo the Great (Jordan of the Capets).

- Adalhaid (774). He was born while his parents were on the campaign in Italy. He was sent to France, but he died before he arrived in Lyon.

- Rotruda (or Hruodrud) (775-6 June 810)

- Luis (778-20 June 840). Lotario twin. Crowned king of Aquitaine (781), Roman emperor sacral (813) and emperor Senior (814).

- Lotario (778-6 February 779/780). Luis' twin. He died during his childhood.

- Bertha (779-826)

- Gisela (781-808)

- Hildegarda (782-783)

- He contracted marriage with Fastrada from 784 until his death (794). The fruit of this marriage was born:

- Teodrada (784-?), abbess of Argenteuil.

- Hiltruda (787-?)

- His last wife was Lutgarda, with whom he married in 794. No son of this marriage was born.

Married couples and illegitimate children

- His first known concubine was Gersuinda. She had:

- Adeltrude (774-?)

- His second known concubine was Madelgarda. She had:

- Rutilda (775-810), Abbey of Faremoutiers

- His third known concubine was Amaltruda de Vienne. She had:

- Alpaida (n. 794)

- His fourth known concubine was Regina. She had:

- Drogo (801-855). Archbishop of Metz since 823 and Abbot of Luxeuil.

- Hugo (802-844), archi-chancellor of the Empire.

- His fifth known concubine was Adelinda. She had:

- Richbod (805-844). Abbot de Saint-Riquier.

- Theodoric (807-?)

Ancestors

| 16. Ansegisel | ||||||||||||||||

| 8. Pipino de Heristal | ||||||||||||||||

| 17. Cumberland Bega | ||||||||||||||||

| 4. Carlos Martel | ||||||||||||||||

| 9. Alpaïde de Bruyères | ||||||||||||||||

| 2. Pipino the Breve | ||||||||||||||||

| 10. Lamberto de Hesbaye | ||||||||||||||||

| 5. Rotrudis de Tréveris | ||||||||||||||||

| 1. Carlomagno | ||||||||||||||||

| 6. Caribbean of Laon | ||||||||||||||||

| 13. Bertrada de Prüm | ||||||||||||||||

| 3. Bertrada de Laon | ||||||||||||||||

| 7. Gisela de Laon | ||||||||||||||||

Titles

| Real Titles Carolingios | ||

| Predecessor: Pipino the Breve | King of the Francos 768-814 together with Carlomán I (768-771) and Carlos el Joven (800-811) | Successor: Luis I el Piadoso (Ludovico Pio) |

| Predecessor: Desiderio | King of the Lombards 774-814 together with Pipino de Italia (781-810) and Bernardo I (810-814) | Successed by: Bernardo I of Italy |

| Predecessor: Title created | Emperador carolingio 800-814 together with Luis I (813-814) | Successor: Luis I el Piadoso (Ludovico Pio) |

Contenido relacionado

Geocentric theory

Dry Law

Baal