Celtic music

Celtic music is the term used to describe a broad group of musical genres that stem from the popular musical tradition of peoples considered to be of the Celtic tradition in Western Europe. As such, there is no real body of music that can be described as Celtic, but the term serves to unify both strictly traditional music from certain geographical regions, and a type of contemporary music rooted in folkloric music with the same ethnological and musical origin.

The term mainly means two things: firstly it is the music of peoples who call themselves Celtic, as opposed to French music or English music, defined as existing within clear political boundaries. Secondly, it refers to the characteristics that would be unique to the music of the so-called Celtic nations. Some, such as Geoff Wallis and Sue Wilson in their The Rough Guide to Irish Music, insist that many of the traditions lumped together under the label "Celtic" are ostensibly different from each other (for example, Gaelic and Breton) and actually have little or nothing in common. Others, notably musicians such as Alan Stivell, say they do, consistent with older studies.

Often, because of its wide spread, the term "Celtic music" is applied to the music of Ireland and Scotland as both places have produced well-known styles that share many obvious common features, both musically and physically. linguistic (Gaelic culture). However, it is notable that traditional Irish and Scottish musicians avoid the term Celtic music, except when forced to do so by market needs, and when produced at Celtic music festivals outside their borders. The definition is further complicated by the fact that independence allowed Ireland to promote Celtic music as a specifically Irish product, thereby blurring its musical ties to neighboring Scotland (ties that have been largely re-established by modern musicians).. Scots and Irish, although distinct and separated politically, share the same cultural ancestry and, therefore, one can speak of a Celtic (or Gaelic) musical heritage common to both.

These Gaelic styles are internationally renowned due to the influence of the Irish and Scottish in the English-speaking world, especially in the United States, where they had a profound impact on American music such as bluegrass and country.

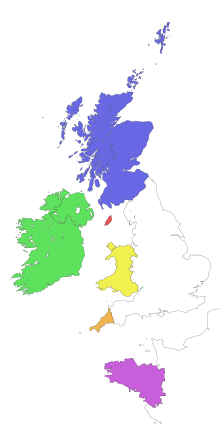

Music from Wales, Cornwall, the Isle of Man, Brittany, Galicia, Asturias, and parts of Cantabria, León, and Portugal are also often labeled "Celtic music." The Celtic music movement, romantic in nature [citation needed] and sometimes linked to the claims of cultural and national minorities, is particularly strong in Brittany, where various Celtic music festivals they take place throughout the year, in parallel and in accordance with other traditional celebrations (local festivals and festoù-noz) in which Breton music has a prominent place and which host bands and musicians from other countries Celtic tradition. Similarly, Wales maintains its old celebrations, such as the Eisteddfod. There is also a dynamic music scene within the foreign communities of Irish and Scottish origin, especially in Canada, where groups of the Breton tradition come together, and in the United States.

Divisions

In the book Celtic Music: A Complete Guide, June Skinner Sawyers recognizes six Celtic nations divided into two groups based on their linguistic heritage:

- The group of the Q-Celtics are the Irish, Scottish and Manes.

- The group of the P-Celtics are those that come from Cornwalls, Brittany and Wales.

Musician Alan Stivell uses a similar dichotomy between the Goidelic (Irish, Scottish, and Manx) and Bryttonic (Breton, Welsh, and Cornish) branches, which differ "mostly by extended range (sometimes more than two octaves) of Irish and Scottish tunes and the closed range of Breton and Welsh tunes (often reduced to half an octave), and by the frequent use of the pure pentatonic scale in Gaelic music."

Discussion and criticism

The debate refers to the apparent lack of common ground that currently unites the aforementioned Celtic peoples. While the ancient Celts undoubtedly had their own musical styles, the actual sound of their music remains a complete mystery.

There is also enormous variation between "Celtic" regions. Ireland, Scotland and Britain have kept traditions of language and music alive (largely as a form of resistance to outrages committed against their people and culture by England and France in the past), and there has been a recent resurgence of interest in Wales. However, Cornwall and the Isle of Man only have small renewal movements that have yet to take hold. Galicia does not currently have a Celtic language despite the fact that the entire western part of the Iberian Peninsula had Celtic languages in pre-Roman times, as did much of Europe. In the case of Spain, Galician and Asturian music is often referred to as Celtic music, probably due to the enormous Celtic archaeological legacy that remains in these lands. It should be noted, for example, that the only Celtic settlement (Castro de Santa Trega), intact in all of Europe, is in Galicia. The same can be said of the music of Cantabria, part of León and northern Portugal. Thus, traditionalists and scholars discuss whether or not the Celtic lands currently have connections to each other. Should the folklore of those regions be called Celtic music where some cultural, linguistic or archaeological remnant of the ancient Celtic peoples currently survives? The question remains open and has full validity.

Critics of modern Celtic music claim that idea is a marketing concoction, designed to stimulate regional identity in the minds of a group of consumers. June Skinner Sawyers, for example, notes that "Celtic music is a marketing term that I am using, for the purposes of this book, as a matter of convenience, knowing full well the cultural baggage it brings with it." This commercial idea was popularized by the first man who, in the late sixties, mixed the music of the so-called Celtic nations with a modern twist in his recordings and concerts, such as on the 1972 album Renaissance of the Celtic Harp< /i>: Breton Alan Stivell. Despite the fact that this composer is one of the main modern promoters of this type of music, he did not create the term.

The ascription of the musical traits of each of the so-called Celtic regions to those of the closest musical traditions (for example, the stylistic belonging of Breton music to the French sphere, or that of Galician and Asturian music to the of Hispanic music), as well as the enormous disparity between one Celtic music and another, reinforces, according to its critics, the idea that «Celtic» as a body of music with common elements and well differentiated from the rest of the continent's traditions is a modern romantic invention. whose origin is the imitation of Irish and Scottish patterns by other folklores. They affirm that Celtic music does not exist, but rather Irish, Scottish, Breton, Galician, Asturian, etc.

Many also believe that adherence to a supposedly common Celtic tradition by historically and culturally very different regions (except Scotland and Ireland, which do share numerous identity traits) responds, beyond its debatable theoretical basis, to the need of linguistic and cultural minorities to move away from the standardization imposed by their respective metropolises and to establish bonds of solidarity among themselves.

Styles of Celtic music

The identification of common features in Celtic music is problematic. Most of the popular musical forms today regarded as distinctively Celtic were (and often still are) common to many other places in Western Europe. There is debate as to whether the Irish jigs were adapted from the Italian jig, typical of the Baroque era, for example, while the polka originates from the Czech and Polish tradition.

There are musical genres and styles unique to each Celtic country due to individual singing traditions and the characteristics of their specific languages. Strathspeys are specific to the Scottish Highlands, for example, and some have theorized that their rhythms mimic those of the Scottish language.

Instruments

The basic instruments usually used in the composition and performance of Celtic music are:

- The gaita,

- the budan,

- the violin,

- the tin whistle,

- the low whistle,

- the Irish transvestite,

- the bomber

- the Celtic harp.

Festivals

The Celtic music scene involves a large number of music festivals.

Celtic Fusion

The oldest musical tradition that falls under the banner of Celtic fusion originated in rural North America in the early colonial period and incorporated Scottish, Irish, English and African influences. Variously referred to as roots music, American folk music, or old-time music, this tradition has exerted a strong influence on all forms of American music, including country, blues, and rock and roll. In addition to its effects in the long term in other genres, it meant the first large-scale modern blending of musical traditions from various ethnic and religious communities within the Celtic diaspora.

In the 1960s, various bands performed modern adaptations of Celtic music drawing on influences from several Celtic nations at once to create a modern pan-Celtic sound. Some of them include the bagadoù (Breton bagpipe bands), Fairport Convention, Pentangle, Steeleye Span and Horslips.

In the 1970s, Clannad initially started out on the folk and traditional scene, later going on to bridge the gap between traditional Celtic music and pop music in the 1980s and 1990s incorporating elements of new age, jazz and folk rock. Traces of Clannad's legacy can be heard in the music of many artists including Enya, Altan, capercaillie, The Corrs, Lorraine McKennitt, anuna, Riverdancing and U2.

Later, with the appearance of the fusion of hard rock with Celtic music by Jethro Tull and Thin Lizzy, and from 1982 with the invention made by The Pogues of Celtic punk; there has been a movement to incorporate Celtic influences into other genres of music. Bands like Flogging Molly, Black 47, Dropkick Murphys, The Young Dubliners, marxman or The Tossers introduced a hybrid of Celtic rock, punk, reggae, hardcore, and other elements in the 1990s, which have become popular with Irish-American youth.

Today there are Celtic-influenced subgenres in virtually every type of music, including electronic, rock, metal, punk, hip hop, reggae, new age, house, ska, Latin, Andean, and pop. Taken together, these modern interpretations of Celtic music are sometimes referred to as Celtic fusion. Some current examples are: the Spanish band Xera (which combines Celtic and traditional Asturian music with electronic music), and the Argentine band Celtic Underground (which fuses Scottish music with electronic and pop music).

Among the different subgenres is the so-called folk metal, resulting from the mixture between heavy metal and Celtic music, which has been quite successful in recent years. As in Viking metal, the basis of Celtic can vary but those that combine Celtic rhythms with black metal or death metal are common. Some groups of this Celtic metal are Aes Dana, Bran Barr, Cruachan, Crystalmoors, Ensiferum, eluveitie, Elvenking, Heol Telwen, Landevir, Saurom, Skiltron, Triddana and waylander.

Other modern adaptations

Outside America, the first deliberate attempts to create pan-Celtic music were made by the Breton Taldir Jaffrennou, who had translated songs from Ireland, Scotland and Wales into Breton in the interwar period. One of his main works was to bring Hen Wlad Fy Nhadau (the Welsh national anthem) to Britain and create lyrics in Breton. Over time, this song became Bro Goz va zadoù, the most widely accepted Breton anthem. In the seventies, the Breton Alan Cochevelou (future Alan Stivell) began to play a mixed repertoire of the main Celtic nations on the Celtic harp created by his father.

Modern music can also be called Celtic because it is written and recorded in a Celtic language, regardless of musical style. Many of the Celtic languages have experienced a resurgence in recent years, fueled in part by artists and musicians who have adopted them as hallmarks of identity and distinction. In 1971, the Irish band Skara Brae recorded their first and only LP with all their songs in Irish Gaelic. In 1978 Runrig recorded an album in Scottish Gaelic. In 1992 Capercaillie recorded A Prince Among Islands, the first Scottish Gaelic record to reach the UK top 40. In 1996, a song in Breton represented France in the Eurovision Song Contest 1996. Since about 2005, Oi Polloi (from Scotland) have recorded in Scottish Gaelic. Mill a h-Uile Rud (a punk band from Seattle) recorded in that language in 2004.

Also, several contemporary bands have songs in the Welsh language such as Ceredwen, which fuses traditional instruments with trip hop rhythms, the Super Furry Animals or Fernhill. The same phenomenon occurs in Brittany, where many singers record their songs in Breton, traditional or modern (hip hop, rap, etc.).

Celtic music in Europe

In Europe, groups and soloists from some of the so-called Celtic nations stand out. Thus, in Ireland we find The Chieftains, Dervish, alone, lunasa, Planxty, Celtic Woman, The High Kings, The Dubliners, Tommy Peoples, Liz Carroll, Patrick Street and The Bothy Band. In Brittany, Wig A Wag, Tri Yann, gwendal, Nolwen Leroy, Soldier Louis, stone age and Sacrée Bordée. In Scotland, The Tannahill Weavers, Wolfstone, The Corries and Alasdair Fracer, as well as Filska (from the Shetland Islands).

Apart from those areas, over the years Celtic-inspired groups have sprung up in other countries, such as Anach Cuan and the Glen of Guinness (in Switzerland), Omnia (in the Netherlands), Terrafolk (in Slovenia), Skáld, Oubéret and Celtic Origine (in France).

Celtic music in Spain

In Spain, the Ortigueira Festival (La Coruña) is internationally known as one of the showcases for Spanish groups, as well as the Avilés Interceltic Festival or the Folkomillas Festival in Comillas. There are various groups and authors who adapt more or less to the original definitions of what is meant by Celtic music.

Most of the groups and soloists classified as Celtic music sing in Galician or Asturian, since Celtic music is part of the traditional folklore of Galicia and Asturias. Thus, from Galicia they are Brat, Luar na Lubre, Milladoiro, you Cempes, Carlos Nunez, Berroguetto, Susanna Seivane, Cristina Duck, Xose Manuel Budiño, Mercedes Pawn, Anxo Lorenzo (who fuses Celtic styles with electronic tendencies) and Alan Bique. They are from Asturias José Ángel Hevia (precursor of the electronic bagpipe), Weaver, Felpeyu, Llan de Cubel and Corquiéu. Likewise, we also find groups in other areas of Spain of "Celtic tradition" such as Luétiga, Garma, Gatu Malu, Cahórnega, Naheba, Atlántica and Cambera'l Cierzu in Cantabria or Antubel, Gandalf, Tsuniegu, Olwen, Medulia and L´ Arcu la Vieya in León.

It is also interesting to highlight the existence of folk groups outside the more traditional regions, such as Ima Galguén in the Canary Islands, Winterfell, Sláinte and Lád Cúig in Catalonia, Rare Folk, Mussels, Stolen Notes and Gan Ainm in Andalusia, O´ Carolan in Aragon, Hibai Deiedra and Kepa Junkera in the Basque Country, Acetre in Extremadura or Zamburiel and Kinnia in Madrid.

Other groups, such as Triquel, Celtas Cortos or Akelarre AgroCelta, as well as more recently El Sueño de Morfeo, explore certain characteristics of this musical style, although it cannot be said that they perform «Celtic music» on a regular basis.

Celtic music also has its place in Spanish rock. One of the first Spanish groups to merge the aspects of Celtic music with Heavy metal was Ñu. Later, bands such as Lándevir or Saurom would also be found in this subgenre. However, the most successful group has been Mägo de Oz with its fusion of metal and Celtic sounds.

Celtic music in America

There is a dynamic growth of this genre in America, including dance and research in areas related to Celtic societies. Celtic music in Latin America is resignified, since it receives various musical contributions from each country where it is performed.

In North America it has a notable presence due to European immigration, mainly Irish, with the emergence of artists like Loreena McKennitt or Michael Flatley, and festivals such as Celtic Colours, which take place on the island of Cape Breton.

Argentina received immigrants of Celtic origin from all over Europe: Galicians, Asturians, Irish, Welsh and Scottish, so their descendants recreate their melodies, some traditional and others of original composition, but always with Celtic reminiscences. One of the pioneering Celtic music groups in this country has been Duir, who interpret traditional themes from Ireland, Scotland, Wales and Brittany. His repertoire includes both dances and songs -in English, Irish Gaelic, Welsh and Breton-. The instruments played are bodhran, Irish flute, tin whistles, mandolin, acoustic guitar and bouzouki. Among the most prominent artists are Santiago Molina, Athy (harpist and composer who fuses his harp with other ethnic instruments as well as mixing Celtic music with styles such as new age, flamenco, tango, electronic music, jazz or blues), Ara Solis, Arween, Calath, Celtic Underground, Fillos do Vento, Gael, Gustavo Fuentes, Kells, Na Fianna, You Furafos, seven nets, Xeito Novo, Bri - Celtic Folk and xold

In Chile there are bands like Breogan, Celtic Dancing Band, Riveira (who performs for the first time in this country the fusion of Celtic folk with acoustic rock), keltoiband, mandrago, Ta Fechu (the first Chilean band invited to the Lorient interceltic festival and the first nominated for an international award such as the amas awards), The Eringo, dana, Celtic Andes, Finisterre, Ensemble Voices of Time, Gwyddyon, in addition to the dissolved Banda Celtamericana (which was the first Chilean group of its kind to tour the United Kingdom and Ireland in 2007).

In Colombia, groups like Perceval (the first group from the capital of that country to publish a record of this genre), Mithril (band), Ogmios, Celtic Spirit, I know Dublin and La Montaña Gris (the only Spanish-American group that made two continental tours to promote their recordings).

In Costa Rica there are groups Gray Pilgrim and Arbore Lume

In Mexico, bands and soloists such as Cross country, An Bodhran, ontophony, Ogham Ensemble, the Bagpipe Band of the San Patricio Battalion and harpist Cynthia Valenzuela.

In Uruguay, performers such as Lorraine Lords, The Casáls, Griannan or the Southern Cross Pipe Band.

In Venezuela, Gaelica stands out.

Contenido relacionado

Viggo Mortensen

Typography

Percussion instrument