Celtiberian language

The Celtiberian language or Celtiberian was a paleo-Hispanic language belonging to the group of Celtic languages of the Indo-European family. It was spoken in the central area of the Iberian Peninsula, in the ancient territory of Celtiberia, being known about it thanks to some 200 inscriptions written mainly in Celtiberian signario, but also in Latin alphabet.

These Celtiberian inscriptions are distributed throughout the Ebro valley and the headwaters of the Tagus and Duero: silver and bronze coins, silver and bronze tesserae, bronze plaques, black varnish ceramics, amphoras, spindle spindles, stone plates, etc.

Although the precise chronology of most of the Celtiberian inscriptions is unknown, the oldest are documented in the first half of the 2nd century BC. C. and the most modern at the end of the 1st century B.C. C. or perhaps at the beginning of the I d. c.

Among the continental Celtic languages, Celtiberian is worse documented than Gaulish, but better than Lepontic and Galatian.

History

Judging by the archaeological record, the Celts arrived in the Iberian Peninsula in the 13th century B.C. C. with the great expansion of the peoples of the culture of the urn fields, then occupying the northeast region. In the seventh century B.C. C., during the Hallstatt culture they spread over large areas of the plateau and Portugal, some groups reaching Galicia. However, after the Greek founding of Masalia (present-day Marseille), the Iberians reoccupied the middle valley of the Ebro and the northeast of the peninsula from the Celts, giving rise to new Greek settlements (Ampurias). The Celts of the peninsula were thus partially disconnected from the rest of their continental relatives.

In this way, with time, isolation and the very possible influence of other pre-Indo-European languages spoken in the peninsula, an independent language of Common Celtic, the Celtiberian language, developed.

This was the language spoken by the Celtiberians, a group of tribes and peoples who inhabited the northeast of the central area of the Iberian Peninsula, of Celtic culture but with Iberian influence, adopting from them, among other features, their system of writing as will be explained later. Their territory extended through the Central System and the upper valley of the Ebro, and among them were mainly the Arevacos, the Pelendones, the Lusones, the Titos, the Belos, and perhaps the ancient Olcades, the turbolets, and berons. In 133 B.C. C., after the fall of Numancia, its territory became part of the Roman province of Hispania Citerior.

Writing

The Celtiberian script is an almost direct adaptation of the northeastern Iberian script to the particularities of the Celtiberian language. Like its model, this writing presents signs with syllabic value, for the plosives, and signs with alphabetic value for the rest of the consonants and vowels. From the point of view of the classification of writing systems, it is neither an alphabet nor a syllabary, but a mixed script that is normally identified as a semi-syllabary. This signario presents the inconveniences of syllabaries, since neither the occlusive+liquid groups nor the final plosives can be correctly represented, which, unlike the Iberian language, did possess the Celtiberian language. The basic sign is made up of 26 signs, instead of the 28 of the original northeastern Iberian sign, since one of the two trills and one of the three nasals are eliminated. The Celtiberian sign has two variants differentiated by the values of the nasal signs: in the eastern variant the deleted nasal is the one that in Iberian is identified with m´, while in the western variant the deleted nasal is the one that in Iberian is identified with m, a circumstance that is interpreted as proof of a double origin. In addition, it should be noted that some of the inscriptions of the western variant show indications of use of the dual system that allows differentiating the voiceless dental and velar plosive syllabograms from the voiced ones with an added line: the simple form represents the voiced and the complex form the voiceless.

Linguistic features

Despite the more than possible influence of other pre-Indo-European autochthonous languages of the peninsula, the Celtiberian language preserved most of the grammatical structures of the Celtic languages.

- IE *p-, ♪ VpV ▪ Ø. The loss of the consonant /p/ at the beginning of the word and intervocálica position is the definitive trait that catalogs the cellulober as a Celtic language and that differentiates it from the lusitano. Common Celtic orcLatin porcus, lusitano porco- 'near'. Examples: Oilaunika 'dominator'2-mn-ika.

- IE *kw ku: One of the main characteristics of the celltyber is that, unlike the other continental Celtic languages such as the gallon or lepontic, this is a Celtic-Q language, being the previous Celtic-P languages, that is, that the PIE sound *kwIt didn't become ♪ but ♪. This can be seen in the bronze of Botorrita where the indo-European copulative conjunction *-kwe ('y') -ku.e and no - What? as it is in galo and lepontico. This is a trait that shares with the Irish and Gaelic languages of Scotland. Outside of the Celtic languages, the lusitano and Latin are also languages-Q.

- IE *ē/*eH/*eh1 = ī. Known trait of the common Celtic exemplified in the word of the gallon for ‘rey’ rix in opposition to the Latin rēx (both from IE *rēg-s). In Celtibérico it is presented in its own name Munerigios which literally means ‘king or mountain prince’ (IE *moni-rēg-yos)

- IE *ō/oH/*eh3 = ā: Vocálica Mutation of the common Celtic that consists of moving in -ā- the vocal IE -ō- (as well as cārnu ‘cuerno’, IE *kōrnos, Cfr. lat. hornus).

- Example: The Gentle Akaizokum forms on the personal name Akaizos /āk-ais-os/ which comes from an indo-European adjective ōk-us ‘rapid’ whose comparative ōk-is means ‘very fast’. Share with the galo Diācus “slow, lazy”di-ōkusAnd with the astur Acula ‘rapidilla’.ōku-la. zaunom ‘donado’ Δ*dā-mn-om ‘dō-mn-om.

- IE *ō/oH/*eh3 = ū at the end of syllable. Another vocálic mutation of the common Celtic. The imperative Tatuz /datuz/ ‘he must donate’ comes from an IE *dō-tōd.

- IE *n 한 an and *m ה am: Vocálica performance of the nasals in grade zero an / am, in front of the Latin that makes in / em. arkanta (K.1.3) argatLatin argentum ≤2argn.tom. tekametinas (K.1.1) ≤1 km / --eto ‘tenth’, Latin decem.

- IE *r 한: Vocálica performance of the liquid probe to grade zero r. ri ante oclusiva. sekobiriked /segobriged/ nertobis /nertobrixs/ *nertobhr-gh-s. Common Celtic briga ‘colina’.

- IE *l 한 li: Vocálica performance of the liquid probe to grade zero l: li ante oclusiva: The Gentile litanokum formed on Lithuanian ‘Ancho, ample’. *pl-tH-nos. Galo Litana.

- Comparative training -ais/-is and the superlative in -aisam/isam against the Western and Celtic dialects of Beturia that form the comparative in - Yeah. and the superlative in -Am. Examples: āku ‘rapid’. āk-ais-os ‘very fast’: Akaizos (gifting) Akisos)/ bias ‘force, victory’. seg-ais-a ‘the very strong’: Sekaiza (common cell) Segisa) / Latvian ‘ancho’. let-aisama ‘the very ‘ancha’: Letaisama (common cell) Letisama).

- Celtish presents a relative pronoun - Yeah. completely declined (as he did, for example, the Greek attic), which is not preserved in any of the other Celtic languages, and, apart from that already named kue(in Latin) that, Greek attic you (τε)), particles nekue, ‘ni’ (in Latin neque and in Greek attic mēte (μكε) mē (μγ“no” + you ‘and’ ” IE *kwe), and Go., ‘o’ (in Latin - Come on. and Greek attic ē ( ) *ē-we).

- Subjunctive training s, gabiseti (‘tome’) gabid), robiseti, auseti (compare with the umbro ferest ‘haga’ or ancient Greek deiksēi (δεείה, aorist subj.) / deiksei (δείεεει, indicative future) (‘(what) shows’).

- Fricative result z resulting from /s/ and /d/ intervocálicas:

- Examples: *bhedhom bezom ‘mina’ (gift bedom ‘fosa, canal’). *seghisa /2005 Segaisa (written as Sekaiza) Segisa). *Ups-edyo * Useizu (common cell) Uxedia Δ* Ups-edya. *sosyo soz 'this' sosio).

Given the already explained difficulties that the Iberian alphabet poses in its adaptation to the phonological system of a Celtic language, for the reconstruction of the Celtiberian phonology, the inscriptions and transcriptions of names in the Celtiberian language are also used but written in documents and texts latinos.

| Occlusive | Africa | Fellowship | Nasales | Liquids | Approximate | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bilabial | sorda | /p/ .b▪♪ | /m/ .m, n▪ | /l/l▪ /r/.▪ | /w/ .u▪ | ||

| Sonora | /b/ .b▪ | ||||||

| Alveolar | sorda | /t/ .t▪ | /ts/ Δ's' | /s/ .ś▪ | /n/ .n, m' ▪ | ||

| Sonora | /d/ .t▪ | /dz/ .z▪ | |||||

| Velar | sorda | /k/ .k▪ | |||||

| Sonora | /g/ .k▪ | ||||||

*The signs between bars, / /, indicate the reconstructable phonemes for Celtiberian and < > its spelling in Iberian alphabet

The fact that there are voiceless and voiced plosives despite using the same spelling to represent them is deduced on the one hand because the other known Celtic languages have both types of sounds, and on the other hand because of the inscriptions in the Latin alphabet, since they show that these sounds were present in the spoken language.

The existence of other sounds is more uncertain; an example is that many words with the grapheme z < /s/ intervocalic, or < sequence -dyo, corresponds in the Latin inscriptions to <d>, thus the name of the city of Sekaiza in Latin is transcribed as Segeda, so it deduces that said word must sound something like [se'gêdza], with affricate, in Celtiberian.

Morphologically, one of the characteristics of Celtiberian is the root o in the genitive singular case in -o, compared to -i Found in other Celtic languages. Another characteristic is the verb ending -tuz which presents the imperative from the IE imperative -tōd (loutuz 'lava tu' < *low-tōd.

Despite not being easy to interpret or translate on all occasions, from the Celtiberian inscriptions and the most abundant endings in them we can conjecture some of the morphological features of the Celtiberian. In this way we can deduce that with respect to the declinations, there would be 5 or 6 cases, the same as in the proto-Celtic. The following table approximates the cases of inflection for singular masculine nouns.

| Items in -a | Topics in - or | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Galo | Celtiber | Galo | Celtiber | |

| Nominative | - Yeah. | - Yeah. | - You. | - You. |

| Acute | -in, | -Am | -on, | - |

| Genitivo | -as, | - | -I | os, -o (?) |

| Dativo - Ablativo | -i | -I'll do it. | -u(i) | -I'll do it. |

| (Locative) | - Hey. | -? | - Hey. | - You will. |

Also the dative in the plural would be -b-.

The plural of Celtiberian is a reflection of Indo-European -*es or, sometimes following the later development of some European dialects of Indo-European itself, we find plurals from *-oi. This manifests a fairly typical nominal inflection for an Indo-European language. We only find a strange singular ending in -o that rarely appears in Indo-European languages.

Regarding conjugation, although only two verbs have been identified in Celtiberian inscriptions, typical Indo-European endings are clearly observed in them: -t (Latin -t, Greek -ti) for the third person singular and -nti (Latin -nt, Greek -nti, Sanskrit -nti) for the third plural.

The linguistic typology of order is subject, verb and predicate, which is considered, based on other archaic languages such as Hittite, Sanskrit and Latin, the basic one for the reconstructed Proto-Indo-European language.

Texts

Some 200 inscriptions written mainly in the Celtiberian language, but also in the Latin alphabet, have reached us from the Celtiberian language, of which the following are noteworthy:

Botorrita bronzes

The Botorrita bronzes are four inscribed bronze plates, from the Cabezo de las Minas site (Botorrita, Zaragoza). The first, third and fourth contain texts in the Celtiberian language and script (eastern variant), while the second contains a text in the Latin language and script that contains the sentence of a trial held on May 15, 87 BC. C. in Contrebia Belaisca, which is why the site of Cabezo de las Minas is identified with this city. The content of the first bronze is less precise, but it is assumed that it should also be a legal text. The third bronze is the longest paleohispanic text, although its content is basically a long list of onomastic formulas in which some 250 people are identified. The fourth bronze is very fragmented, but it is in line with the first. The four bronzes are currently deposited in the Museum of Zaragoza. An example of the transcription of one of these bronzes is the following:

- A.1. tirikantam: berkunetakam: tokoitoskue: sarnikio (:) kue: sua: kombalkez: nelitom

- A.2. nekue [: to: u]ertaunei: litom: nekue: taunei: litom: nekue: masnai: tizaunei: litom: soz: auku

- A.3. aresta[lo]: tamai: uta: oskues: stena: uerzoniti: silabur: sleitom: konskilitom: kabizeti

- A.4. kantom [:] sankilistara: otanaum: tokoitei: eni: uta: oskuez: boustomue: koruinomue

- A.5. makasiamue: ailamue: ambitiseti: kamanom: usabituz: ozas: sues: sailo: kusta: bizetuz: iom

- A.6. asekati: [a]mbitinkounei: stena: es: uertai: entara: tiris: matus: tinbituz: neito: tirikantam

- A.7. eni: oisatuz: iomui: lists: titas: zizonti: somui: iom: arznas: bionti: iom: kustaikos

- A.8. arznas: kuati: ias: ozias: uertatosue: temeiue: robiseti: saum: tekametinas: tatuz: somei

- A.9. enitouzei: iste: ankios: iste: esonkios: uze: areitena: sarnikiei: akainakubos

- A.10. nebintor: tokoitei: ios: uramtiomue: auzeti: aratimue: tekametam: tatuz: iom: tokoitoskue

- A.11. sarnikiokue: aiuizas: kombalkores: aleites: iste: ires: ruzimuz: abulu: ubokum

First bronze of Botorrita, face A (Zaragoza): Probably a legal text, written in Eastern Celtibic sign. Transcript of Carlos Jordan, 2004.

Bronze from Luzaga

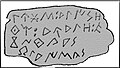

This is a small 16 x 15 cm bronze plaque that contains a text in the Celtiberian language and script in its western variant, where the use of the dual system is detected, which makes it possible to differentiate voiceless dental and velar plosives from voiced ones. The text is made with the dotted technique and is distributed in eight lines containing 123 signs. The plate has seven regularly distributed holes and more than a third of the surface is free of writing.

Bronze by Cortono

This is a metal sheet found in Medinaceli (Soria) corresponding to the Roman city Cortonum. With five lines of Western Celtiberian text. It was found without a clear archaeological context, although its content could refer to a pact between peoples and be documented between the 2nd – 1st centuries BC. c.

Inscription of Peñalba de Villastar

Text written in the Latin alphabet found in the town of Villastar (Teruel), and which is probably a votive text:

- ENIOROSEI

- VTA TIGINO TIATVNEI

- ERECAIAS TO LVGVEI

- ARAIANOM COMEIMV

- ENIOROSEI EQVEISVIQVE

- OCRIS TOGIAS SISTAT LVGVEI TIASO

- TOGIAS

Whose translation could be:

"To Einor(o)sis and Tiatú de Tiginos we grant swells and Lugus a field; to Einor(o)sis and to Equaesos Ogris subject the protections of the fertile land to Lugus the protections of the dry land."Transcript Meid, 1994.

Meid's translation is considered incorrect since Jordán Cólera translated somei eni touzei from Botorrita as 'in this territory' proving that eni corresponds to the preposition 'en' (eni < *h₁en-i, cf. Common Celtic eni, Latin in). This shows that neither eniorosei nor tiatunei are datives but locatives. Tigino is a genitive that depends on tiatunei: 'In Orosis and the tiatuno of Tigino. Alternatively:

«In Orosis and the extension of Tigino (probl. a river) we dedicate the grooves (labrated fields) to Lugus. In Orosis and Equeisu the mountains, orchards and roofs (houses) to Lugus are. The houses of the area sheltered”.Transcript Prosper 2002.

Gallery: Registration Examples

Contenido relacionado

Peter Cerbuna

Aka

640