Cellular cycle

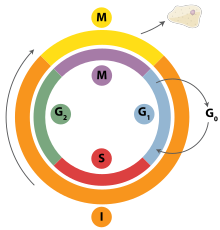

The cell cycle is an ordered set of events that lead to cell growth and division into two daughter cells. The stages are: G1-S-G2 and M. The state G1 means “GAP 1” (Interval 1). The S state represents "synthesis," in which DNA replication occurs. The G2 state represents “GAP 2” (Interval 2). The M state represents "the m phase", and groups together mitosis or meiosis (distribution of nuclear genetic material) and cytokinesis (division of the cytoplasm). The cells that are in the cell cycle are called "proliferating" and those that are in the G0 phase are called "quiescent" cells. All cells originate only from a previously existing cell. The cell cycle begins in the cell cycle. moment in which a new cell appears, a descendant of another that divides, and ends at the moment in which said cell, by subsequent division, gives rise to two new daughter cells.

Cell cycle phases

The cell can be found in two very different states:

- The state of non-division or interfase. The cell performs its specific functions and, if it is intended to advance the cell division, starts by doubling its DNA.

- The state of division, called phase M.

- Interfase

It is the period between mitosis. It is the longest phase of the cell cycle, occupying almost 90% of the cycle. It takes place between two mitoses and comprises three stages:

- Phase G1 Growth o Gap 1): It is the first phase of the cell cycle, in which there is cell growth with protein and RNA synthesis. It is the period between the end of a mitosis and the beginning of DNA synthesis. It lasts between 6 and 12 hours, and during this time the cell doubles its size and mass due to the continuous synthesis of all its components, as a result of the expression of the genes that encode the proteins responsible for its particular phenotype. In terms of genetic loading, in humans (diploids) are 2n 2c.

- Phase S English Synthesis): It is the second phase of the cycle, in which DNA replication or synthesis occurs, as a result each chromosome is duplicated and consists of two identical chromaticides. With the duplication of DNA, the core contains twice as many nuclear and DNA proteins as at first. It lasts about 10-12 hours and occupies about half the time the cell cycle lasts in a typical mammal cell.

- Phase G2 Growth o Gap 2): It is the third phase of cell cycle growth in which protein and RNA synthesis continue. At the end of this period changes in the cell structure are observed under the microscope, indicating the principle of cell division. It lasts between 3 and 4 hours. It ends when chromatin begins to condense at the beginning of the mitosis. The genetic load of humans is 2n 4c, as the genetic material has been doubled, having now two chromats each.

- Phase M (mitosis and cytokinis)

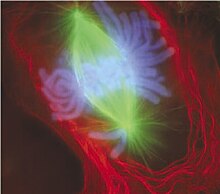

It is the cell division in which a progenitor cell (eukaryotic cells, somatic cells, common body cells) divides into two identical daughter cells. This phase includes mitosis, in turn divided into: prophase, metaphase, anaphase, telophase; and cytokinesis, which begins already in the mitotic anaphase, with the formation of the cleavage furrow. If the entire cycle lasted 24 hours, the M phase would last around 30 minutes.

Cell cycle regulation

The regulation of the cell cycle, explained in 2001 in eukaryotic organisms, can be seen from the perspective of decision-making at critical points, especially in mitosis. Thus, some questions are raised:

- How does DNA replicate once? An interesting question is how cell euploidy is maintained. It happens that in phase G1, the Cdk(cycline) promotes the addition to the DNA replication complex of regulators called Cdc6, who recruit Mcm, forming a pre-replicative DNA complex that recruits the genetic replication machinery. Once phase S is started, the Cdk-S produces the dissociation of Cdc6 and its subsequent proteolysis, as well as the export to Mcm's cytosol, so that the origin of replication cannot, until the next cycle, recruit a prereplicative complex (proteolytic degradations always involve irreversibility, until the gire cycle). During G2 and M maintains the uniqueness of the prereplication structure, until, after the mitosis, the level of Cdk activity falls and the addition of Cdc6 and Mdm is allowed for the next cycle.

- How do you get into mitosis? Cyclin B, typical in the Cdk-M, exists throughout the cell cycle. It happens that the Cdk (cycline) is usually inhibited by phosphorylation through the Wee protein, but at the end of G2, a phosphatase called Cdc25 is activated that eliminates the inhibitor phosphate and allows the increase of its activity. Cdc25 inhibits Wee and activates Cdk-M, which produces a positive feedback that allows the accumulation of Cdk-M.

- How are the chromatid sisters separated? Already in mitosis, after the formation of the acromatic spine and overcoming the point of restriction of the union to filmmakers, the chromatides have to remove their cohesin skeleton, which unites them. To do this, Cdk-M favors the activation of APC, a ubiquitin ligase, by union with Cdc20. This APC ubiquitinizes and favors further degradation in the proteasoma of segurine, inhibitor of the separate enzyme that should scind cohesins.

- How do you get out of mitosis? Once the levels of Cdk-M are high, it seems difficult to stop the dynamics of mitosis and enter into cytokinesis: therefore, this occurs because the APC activated by the Cdk-M, and after a period of time whose control mechanism is still unknown, ubiquitinizes the B cyclin, producing the absolute cessation of Cdk-M activity.

- How is G State maintained1? In phase G1, the Cdk activity is very diminished because: APC-Hct1 (Cdc20 only acts in mitosis) removes all cyclin B; Cdk inhibitors accumulate; the ciclin transcription is diminished. To escape from this rest, you must accumulate G slope1. This is controlled by cell proliferation factors, external signals. Molecular mechanisms for gene transcription activation in phases S and G2 necessary to continue the cycle are passionate: these genes are regulated by the E2F regulatory protein, which binds to DNA promoters of the G cyclins1/S and S. E2F is controlled by the protein of retinoblastoma (Rb), which, in the absence of trophic factors, inhibits the activity promoting the transcription of E2F. When there are signs of proliferation, Cdk-G1 phosphoryla Rb, which loses affinity for E2F, is dissociated from it and allows the genes of phase S to be expressed. In addition, as E2F accelerates the transcription of its own gene, Cdk-S and G1/S fosforilan also to Rb and Hct1 (APC activator, which would degrade these cyclins), there is a positive feedback.

Regulatory components

The cell cycle is controlled by a system that monitors each step taken. In specific regions of the cycle, the cell checks that the conditions are met to move to the next stage: thus, if these conditions are not met, the cycle stops. There are four main transitions:

- Step of G0 a G1: the beginning of proliferation.

- G Transition1 a S: initiation of replication.

- Step of G2 a M: initiation of mitosis.

- Advance metaphase to anafase.

Genes that regulate the cell cycle are divided into three large groups:

- Genes that encode proteins for the cycle: enzymes and precursors of DNA synthesis, enzymes for tubulin synthesis and assembly, etc.

- Genes that encode proteins that positively regulate the cycle: also called protooncogenes. The proteins that encode activate cell proliferation, so that quiescent cells pass to phase S and enter into division. Some of these genes encode the proteins of the cyclin and cyclin-dependent kinase system. They can be:

- Early response genes, induced at 15 minutes of treatment with growth factors, without the need for protein synthesis;

- Late response genes, induced more than an hour after treatment with growth factors, their induction appears to be caused by proteins produced by early response genes.

- Genes that encode proteins that negatively regulate the cycle:Also called tumor suppressant genes.

Cyclins and cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs) are synthesized from proto-oncogenes and work cooperatively to positively regulate the cycle. They phosphorylate serines and threonines of target proteins to trigger cellular processes.

Proto-oncogenes are genes whose presence or activation of oncogenes can stimulate the development of cancer. when they are excessively activated in normal cells, they cause them to lose control of division and continue to proliferate uncontrollably.

Cyclins are a heterogeneous group of proteins with a mass of 36 to 87 kDa. They are distinguished according to the time of the cycle in which they act. Cyclins are very short-lived proteins: after dissociating from their associated kinases, they degrade extremely rapidly.

Cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs) are medium molecular weight molecules that present a characteristic protein structure, consisting of two lobes between which is the catalytic center, where ATP is inserted (which will be the donor of phosphate groups. In the channel at the entrance to the catalytic center there is a threonine that must be phosphorylated for the kinase to act.However, in the center itself there are two threonines that, when phosphorylated, inhibit the kinase and a cyclin-binding region called PSTAIRE. There is a third region on CDKs, remote from the catalytic center, to which the CKS protein binds, which regulates CDK kinase activity.

| Vertebrates | Lifts | |||

| Cdk/cycline Complex | Cycling | Associated Cdk | Cycling | Associated Cdk |

| Cdk-G1 | ciclina D | Cdk 4,6 | Cln3 | Cdk2 |

| Cdk-G1/S | ciclina E | Cdk2 | Cln1,2 | Cdk2 |

| Cdk-S | ciclina A | Cdk2 | Clb5,6 | Cdk2 |

| Cdk-M | ciclina B | Cdk1 | Clb1,2,3,4 | Cdk1 |

Regulation of cyclin/CDK complexes

There are many proteins that modulate the activity of the cyclin/CDK complex. As activation pathways, it is known that the cyclin A/CDK2 complex activates the CAK protein, CDK-activating kinase, and the CAK protein phosphorylates CDK, activating it. Instead, phosphatase PP2a dephosphorylates CDK, inactivating it. In turn, CKI inhibitor complexes such as p27 and p21 have been described that bind to cyclin and CDK at the same time, blocking the active site.

Ubiquitin ligase enzymes lead to ubiquitination of cyclins, marking them for degradation in the proteasome and thereby destroying the functionality of the CDK complex. One ubiquitin ligase enzyme involved in this cell cycle regulation process is the SCF complex, which acts on G1/S cyclins. Another complex called APC (anaphase promoting complex) acts on M cyclins.

- Ciclines G1 and G1/S: During G1, the Rb protein (retinoblastoma) is attached to the E2F protein, which in turn is attached to the DNA promoter of genes necessary for entry into S. By accumulating G slopes1, the ciclina G complexes1/CDK fosforilan a Rb, which inactivates and stops inactivating E2F. E2F activity allows the transcription of genes for phase S. Then they form complexes ciclina G1S/CDK and S/CDK slope, which inactivate more Rb units, further promoting E2F activity.

- Ciclines S: The cyclin complex S/CDK promotes the activity of polymerase DNA and other replication proteins. ORC multiprotein complex orrigin recognition complex) is associated with the origin of DNA replication. In G1 forms the prereplicative complex by partnering with the CDC6 protein and the MCM protein ring. MCMs act as helicases promoting replication. The S/CDK cyclin complex also fosforila the CDC6, leaving it accessible for ubiquitinization by SCF. This prevents a new replication.

- Ciclines M: The M/CDK cyclin complex activated by CAK is present throughout the cycle, but is inhibited by the WEE1 kinase, which phosphorylates. At the end of G2 the CDC25 phosphatase defosforila the CDK and activates the M/CDK ciclin complex. The M/CDK cyclin complex phosphorylates several proteins during mytosis:

- lamins, components of the nuclear foil, at the end of the prophase, to disstructure the nuclear envelope

- protein condensin that condenses chromosomes

- proteins regulating mitotic spine

- APC complex that separates chromatic sisters

- The CDC20/APC complex ubiquites the M cyclins to leave the M phase.

- Tumor suppressant genes: Tumor suppressant genes negatively regulate the cycle. They are responsible for mitosis not continuing if there has been an alteration of the normal process. Among these genes, also called 'verification', are those that encode:

- products that prevent mutations of cycle regulatory genes

- proteins that inactivate CDK by phosphorylation/defosphorylation (e.g. WEE kinase1, CDC25 phosphatase)

- Cycle inhibiting CKI proteins (e.g. p53, p21, p16)

- Rb protein (retinoblastoma protein), whose recessive gene alteration causes retina cancer with that name.

- proteins that induce the output of the cycle to a differentiated cell state or to apoptosis (e.g. Bad, Bax, Bak, Fas ligand receiver)

- Verification is carried out at the control points and ensures the fidelity of genome replication and segregation. Some components, in addition to detecting faults, can start repairs.

The cyclin/CDK synthesis and assembly process is regulated by three types of factors: mitogens, which stimulate cell division; growth factors (GFs), which produce an increase in size by stimulating protein synthesis; and survival factors, which suppress apoptosis.

Checkpoints

There are some control points in the cycle that ensure its progression without failure, evaluating the correct progress of critical processes in the cycle, such as DNA replication or chromosome segregation. These verification routes have two characteristics, and that is that they are transitory (they disappear once the problem that started them is solved) and that they can expire if the problem is not solved after a while. These control points are:

- Unreplicated DNA control point, located at the end of G1 before starting phase S. It acts by inhibiting Cdc25, which is an A/B Cdk1 cycline activator.

- Husband assembly control point (checkpoint of mitosis), before anafase. A Mad2 protein is activated that prevents the degradation of the segurine, which prevents the segregation of sister chromatids until all have joined the spine. It is therefore the control point of the separation of chromosomes, at the end of the mitosis. In the event that it was incorrect, APC's degradation of cyclin B would be prevented.

- DNA damage control point in G1, S or G2. Cell damage activates at p53, which favors DNA repair, stops the cycle by promoting p21 transcription, Cdk inhibitor, and, in the event that everything fails, stimulates apoptosis.

Cell cycle and cancer

Many tumors are thought to be the result of a multitude of steps, of which an unrepaired mutagenic alteration of DNA could be the first step. The resulting alterations cause the cells to initiate a process of uncontrolled proliferation and invade normal tissues. The development of a malignant tumor requires many genetic transformations. The genetic alteration progresses, reducing more and more the responsiveness of the cells to the normal regulatory mechanism of the cycle.

Genes involved in carcinogenesis result from the transformation of genes normally involved in cell cycle control, DNA damage repair, and adhesion between neighboring cells. For the cell to become neoplastic, at least two mutations are required: one in a tumor suppressor gene and another in a proto-oncogene, which then gives rise to an oncogene.

Cell cycle in plants

Development programs in plants, unlike what occurs in animals, occur after embryogenesis. Cell proliferation and division is circumscribed to the meristems, areas in which abundant cell divisions take place, giving rise to the appearance of new organs. The leaves and flowers derive from the stem apical meristem and the floral meristem, respectively, while the root meristem gives rise to the root. The regulation, therefore, of the development programs is largely based on the particular gene expression of the meristems and the concomitant pattern of cell division; in plants there is no cell migration as a mechanism of development. The antagonistic interaction between the hormones auxin and cytokinin seems to be the key mechanism for the establishment of identities and proliferation patterns during embryogenesis and during shoot and root meristem development.

The cell cycle of plants shares common elements with that of animals, as well as certain particularities. Cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs) regulate, to a large extent, the characteristics of the cell cycle. Thus, CDKA (an equivalent to PSTAIRE CDK in animals), is involved in G1/S and G2/M transitions. However, there are some CDKBs, unique to plants, which accumulate in the G2 and M phases and are involved in the G2/M transition.

In terms of cyclins, plants have a greater diversity than animals: Arabidopsis thaliana contains at least 32 cyclins, perhaps due to genome duplication events. The expression of the different cyclins cyclins appear to be regulated by various phytohormones.

- Ciclines D: regulate the transition G1/S

- Ciclines A: intervene in the control of phases S and M

- Ciclines B: involved in G2/M transitions and in control within M phase

- Cyclone H: part of the CDKs activating kinase.

There is a ubiquitin protein ligase complex similar to APC/C (the anaphase promoter complex) and some cyclins, such as B-type cyclins, have ubiquitin-mediated killing sequences in their structure: that is, the process of proteolysis is also a key piece in the regulation of the cell cycle in the plant world.

Phosphorylation of cyclin/CDK complexes at the N-terminus of the CDK element inhibits the activity of the complex; Unlike what happens in animals, where this post-transcriptional modification occurs in Tyr or Thr residues, in plants it only occurs in Tyr residues. In animals, the enzyme that catalyzes this reaction is a WEE1 kinase, and the phosphatase, CDC25; in plants there is a homologue for WEE1, but not for CDC25, which has been found in unicellular algae.

Regarding the inhibitory proteins of the CDK/cyclin complexes, elements similar to the Kip/Cip family of mammals have been described; specifically, in plants these inhibitory elements are modulated by the presence of hormones such as auxin or abscisic acid. These and other phytoregulators play a key role in maintaining meristematic capacity and other developmental traits; this depends on its concentration in a certain zone and on the gene expression program present in that place. For example, the areas that express the protein related to the transport of auxins PINFORMED1 have a high concentration of this phytohormone, which translates into the special location of what will be the promordium of the future leaf; at the same time, this excludes the expression of SHOOTMERISTEMLESS, a gene involved in the maintenance of an undifferentiated state of meristematic stem cells (slowly dividing).

The retinoblastoma pathway (RB/E2F/DP pathway) is not only found in animals and plants, but also occurs in flagellates such as Chlamydomonas. A homologue of the human tumor suppressor, called RETINBLASTOMA RELATED1, described in A. thaliana, regulates cell proliferation in the meriestems; it is regulated via phosphorylation by cyclin-dependent kinases.

A characteristic of great flexibility of plant cells is the permissibility against endoreduplications, that is, duplications of the chromosome endowment (ploidy changes), which are due to the replication of the genetic content without the mediation of cytokinesis. This mechanism is usual in certain tissues and organisms but can also occur in whole plants. Because it is usually associated with a larger cell size, it has been the subject of selection in plant improvement. This fact is explained due to the sessile nature of plant organisms and, therefore, the impossibility of executing avoidance behaviors in the face of environmental stresses; thus, stressed plants with a higher genome copy number could be more resistant. Experimental data do not always support this hypothesis.

Contenido relacionado

Brachychloa

Sympathetic nervous system

Urethra