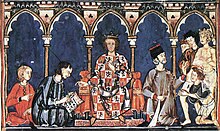

Castilla's crown

The Crown of Castile (in Latin: Corona Castellae), as a historical entity, is usually considered to begin with the last and definitive union of the crowns of León and Castilla, with their respective kingdoms and entities, in 1230, or with the union of the Cortes, a few decades later. In this year 1230, Fernando III "el Santo", King of Castile since 1217 (including the kingdom of Toledo) and son of Alfonso IX of León and his second wife, Berenguela de Castilla, became King of León (whose kingdom included that of Galicia), after the resignation of Teresa of Portugal, the first wife of Alfonso IX, to the rights of her daughters, the infantas Sancha and Dulce to the throne of León in the Concordia of Benavente.

History

From the kingdom of León to those of León and Castilla

The kingdom of León arose from the kingdom of Asturias, which also occupied Asturias de Santillana after the pact between Pedro, Duke of Cantabria, and Don Pelayo of Asturias, which they sealed with the marriage of their children. Castilla was originally a county within the kingdom of León. In the second half of the 10th century, during the Leonese civil wars, it behaved with increasing independence, to finally fall into the Navarrese orbit in the reign of Sancho III the Great, who would secure the county for his son Fernando Sánchez through his wife Muniadona, after the assassination of Count García Sánchez in 1028.

In 1037, Ferdinand I rebelled against the king of León, Bermudo III, who was killed in the battle of Tamarón, becoming king of León through his marriage to Bermudo's sister, Sancha de León. The Castilian county thus became part of the royal patrimony.

Since the beginning of the Reconquest, the border of the Ebro had been disputed between Muslims, Leonese, Navarrese and Aragonese. The Kingdom of Nájera and the Diocese of Calahorra was finally incorporated into the Crown of Castile in 1176 after passing from hand to hand since 923, highlighting its importance on the Camino de Santiago promoted by Santo Domingo de la Calzada and by San Millán de the Cogolla.

On Fernando's death, he divided his estates among his sons. His favorite, Alfonso, received the kingdom of León and the primacy that this title gave her over his brothers. Sancho was given the patrimonial status of his father, the county of Castilla, elevated to the category of kingdom, and the youngest, García, received Galicia. The division did not last long: between 1071 and 1072 Sancho overthrew his brothers and He annexed his states, but he was assassinated this last year, with which his brother Alfonso VI managed to reunify the inheritance of Fernando I, which remained undivided until 1157. This year Emperor Alfonso VII died, bequeathing Leon to Fernando II and Castile to Sancho III. Sancho was succeeded by Alfonso VIII of Castile, and Fernando II was succeeded by Alfonso IX, from whose marriage to Berenguela of Castilla, daughter of Alfonso VIII, fathered Fernando, the future Holy King.

When the son and successor of Alfonso of Castile, Enrique I, died in 1217, Fernando III inherited the Kingdom of Castile from his mother and acceded in 1230, after the death of his father and the resignation of the infantas Sancha and Dulce, to that of Leon. Likewise, he took advantage of the weakness of the Almohad kingdom to greatly advance the Reconquest, taking the Guadalquivir valley while his son Alfonso conquered the Kingdom of Murcia.

The kings of the Crown of Castile (Juana I) held the titles of King of Castile, León, Navarre, Granada, Toledo, Galicia, Murcia, Jaén, Córdoba, Seville, the Algarves, Algeciras and Gibraltar and of the Canary Islands and the Indies and islands and mainland of the Ocean Sea and Lord of Vizcaya and Molina. His heir bore the title of Prince of Asturias.

Kingdoms of the Crown of Castile

Unification of the Courts

By sharing the same king, the Crown of León (kingdoms of León -which already included what had been the taifa of Badajoz-, Galicia and Asturias) was integrated into the Crown of Castile. At the beginning, the courts of the two Crowns met separately, each one in its territory and with the minutes in different languages (Castilian and Leonese and Galician). However, after Fernando III (son of Alfonso IX of León), the joint meeting of the courts ended up being permanent. The Cortes were articulated in three arms that corresponded respectively to the noble, ecclesiastical and citizen estates and although the number of cities represented in Cortes varied over time, it was King Juan I who set definitively the specific cities that would have the right to send procuradores to Cortes: Burgos, Palencia, Toledo, León, Seville, Córdoba, Murcia, Jaén, Zamora, Segovia, Ávila, Salamanca, Cuenca, Toro, Valladolid, Soria, Madrid, Guadalajara and Granada (from 1492).

With Alfonso X, most of the Cortes meetings were joint for all the kingdoms. The Courts of 1258 in Valladolid are From Castiella and from Estremadura and from the land of León and those of Seville in 1261 From Castiella and from León and from all our other Regnos. Later some separate Courts would be held, such as in 1301 (Burgos for Castilla, Zamora for León), but the representatives of cities ask for a return to unification:

The Castilian representatives request: Well, now these courts would do here in Castiella far from those of Estremadura in the land of León, that from now on they would not do it or take it as a spindle

Just like the Leonese: that when oviere de facer Cortes that they do it with all the omnes of my land in one in Leonese lands.

Although at first the individual kingdoms and the cities retained their particular rights (among which were the Fuero Viejo de Castilla or the different municipal jurisdictions of the councils of Castilla, León, Extremadura and Andalusia), it was soon articulated a Castilian territorial right around the Partidas (c. 1265), the Ordinance of Alcalá (1348) and the Laws of Toro (1505) that continued in force until 1889, the year in which the Spanish Civil Code was promulgated.

Patronage and payment of the Vote

The providential justification of the origins of each kingdom and its primacy were a very important issue (not only in the Middle Ages, but throughout the Old Regime), and debates arose as to the supernatural entity that should exercise patronage and in what specific territory, with even tax consequences. The origin dates back to mythologized battles from the VIII to the X, of which the chronicles recorded miraculous interventions: the battle of Covadonga, the battle of Clavijo or the battle of Simancas.

The Spanish language and the universities

In the XIII century there were numerous languages in the kingdoms of León and Castilla such as Castilian, Asturian-Leonese, Basque or Galician. But in this century, Castilian began to gain ground as a vehicular and cultural instrument (for example, the Song of Mío Cid).

In the last years of Fernando III, Spanish began to be used for certain documents. But the Spanish language reached the official title with Alfonso X. From then on all public documents will be written in Spanish; Likewise, the translations, instead of being put into Latin, will be made into that language:

- Mandolo moved from the Arabic language in Spanish because the homnes understood it better and knew the most

Some people consider that the replacement of Latin by Spanish is due to the force of the new language, while others consider that it was due to the influence of Hebrew intellectuals, hostile to Latin because it is the language of the Christian church. [who?] Other sources indicate that the Arabic texts from recently reconquered lands of Al-Andalus were translated into Spanish and not into Latin (due to the greater linguistic simplicity of Spanish).[who?]

Also in the XIII century, a large number of universities began to be founded in the territories that would form the Crown of Castile, some, such as those of Palencia, Salamanca or Valladolid, Complutense de Alcalá will be among the first European universities. In 1492 with the Catholic Monarchs, the first edition of the Grammar on the Castilian Language, by Antonio de Nebrija, was published.

Alfonso X would be succeeded by his son Sancho IV in 1284 and his son Fernando IV in 1295, who during his minority, his mother, Queen María de Molina, would rule the Kingdom.

14th-15th centuries: reign of the Trastámara family

Ascendance of the Trastámara to the throne

When Ferdinand IV died in 1312, his son Alfonso XI acceded to the throne, with another period of regency due to a minority. To protect their interests from attacks by the nobles, the cities organized a General Brotherhood in the Cortes de Burgos in 1315 that would be suppressed later by the monarch, in addition to promulgating the Alcalá Order of 1348 as a symbol of strengthening royal authority.. Upon Alfonso's death in 1350, a dynastic conflict began, framed in the Hundred Years' War, between his sons Pedro and Enrique. Alfonso XI had married María de Portugal, from whom he had his heir, the infante Pedro. However, the king also had several natural children with Leonor de Guzmán, among them the infant Enrique, Count of Trastámara, who disputed the kingdom to Pedro once he acceded to the throne.

In his fight against Henry, Peter allied himself with Edward, Prince of Wales, known as the "Black Prince." In 1367 the Black Prince defeated Enrique's supporters at the Battle of Nájera. The Black Prince, seeing that the king did not keep his promises, abandoned the kingdom, a circumstance that Enrique, a refugee in France, took advantage of to resume the fight. Finally Enrique won in 1369 in the battle of Montiel, and killed Pedro. In 1370, when his brother Tello, Lord of Vizcaya, died, Enrique definitively incorporated the Lordship of Vizcaya into the royal patrimony. In 1379 his son Juan de Trastámara accedes to the throne, who, following the centralizing path of his predecessors, will create the Royal Council in 1385.

As Juan de Gante, brother of the Black Prince and Duke of Lancaster, had married Constanza, daughter of Pedro, in 1371, in 1388 he claimed the Crown of Castile for his wife, legitimate heiress according to the Courts of Seville in 1361. He arrives in La Coruña with an army, takes that city first and, later, Santiago de Compostela, Pontevedra and Vigo and asks Juan to hand over the throne to Constanza.

But he does not accept and proposes the marriage of his son the infant Enrique with Catalina, daughter of Juan de Gante and Constanza. The proposal is accepted, they get married in 1388 and simultaneously the title of Prince of Asturias, which Enrique and Catalina held for the first time, is instituted. This allowed the dynastic conflict to end, by consolidating the House of Trastámara and establishing peace between England and Castile.

Relations with the Crown of Aragon

During the reign of Henry III, royal power was restored, displacing the most powerful nobility. In his last years, he delegated part of the effective power to his brother Fernando de Antequera, who would be regent, along with his wife Catalina de Lancaster, during the minority of his son, Prince Juan. After the Compromise of Caspe in 1412, the regent Ferdinand left Castile, becoming king of Aragon.

On the death of his mother, Juan II reached the age of majority, at the age of 14, and married his cousin María de Aragón. The young king entrusted the government to Álvaro de Luna, the most influential person in his court and allied with the small nobility, the cities, the lower clergy and the Jews. This brought the antipathies of the high Castilian nobility and the Infantes of Aragon, which caused the war between Castile and Aragon between 1429 and 1430. Álvaro de Luna won the war and expelled the infants.

Second succession conflict

Henry IV tried unsuccessfully to restore peace with the nobility, broken by his father. When his second wife, Juana de Portugal, gave birth to Princess Juana, this was attributed to an alleged adulterous relationship between the queen and Beltrán de la Cueva, one of the monarch's privates.

The king, besieged by revolts and the demands of the nobles, had to sign a treaty naming his brother Alfonso heir, leaving Juana out of the succession. After his death in an accident, Enrique IV signs the Treaty of the Bulls of Guisando with her half-sister Isabel, in which he names her his heir in exchange for her marrying the prince chosen by Enrique.

The Catholic Monarchs: union with the Crown of Aragon

In October 1469, Isabel and Fernando, crown prince of Aragon, were secretly married in the Vivero palace in Valladolid. This link resulted in the dynastic union of the Crown of Castile and the Crown of Aragon in 1479 when Fernando acceded to the Aragonese Crown, although it did not become effective until the reign of his grandson, Carlos I. Isabel and Fernando were family related and they had married without papal approval for which they were excommunicated. Subsequently, Pope Alexander VI will grant them the title of Catholic Monarchs.

Due to the marriage of Isabel and Fernando, the king and Isabel's half-brother Enrique IV considers the Treaty of the Bulls of Guisando broken by which Isabel would accede to the throne of Castile upon her death provided she had his approval to marry. Henry IV also wanted to ally the Castilian Crown with Portugal or France instead of with Aragon. For these reasons he declares his daughter Juana la Beltraneja heir to the throne in front of Isabel. When Henry IV died in 1474, a civil war began, which would last until 1479, for the succession to the throne between Isabel's supporters and Juana's, in which Isabel's supporters won.

Thus, after Isabella's victory in the Castilian civil war and Ferdinand's ascension to the throne, the two Crowns will be united under the same monarchs, but Castile and Aragon will be administratively separated, each Crown will retain its identity and laws, the Castilian courts will remain separate from the Aragonese, and the only common institution will be the Inquisition. Despite their titles of Kings of Castile, León, Aragon and Sicily, Ferdinand and Isabella each reigned more in the affairs of their respective Crowns, although they also made common decisions. The central position of the Crown of Castile, its greater extension (3 times the Aragonese territory) and population (4.3 million compared to the close to 1 million of the Crown of Aragon) will make it take the dominant role in the union.

The Castilian aristocracy was powerful thanks to the Reconquest (as Enrique IV was able to verify). Monarchs need to prevail over nobles and clergy. In the year 1476 the Brotherhood Council was founded, which would be known as the Holy Brotherhood. In addition, measures are taken against the nobility, feudal castles are destroyed, private wars are prohibited and the power of the advanced is reduced. The monarchy incorporated the military orders under the Consejo de las Ordenes in 1495, the royal power in justice was reinforced at the expense of the feudal and the Audiencia became the supreme body in judicial matters. The royal power also seeks to control the cities more: thus, in the Cortes of Toledo in 1480, magistrates were created to supervise the city councils. In the religious aspect, religious orders are reformed and uniformity is sought. Jews are pressured to convert and in some cases are persecuted by the Inquisition. Finally in 1492, for those who did not convert, their expulsion was decided, estimating that some 50,000 to 70,000 people had to leave the Crown of Castile. Since 1502, the conversion of the Muslim population has also been sought.

Between 1478 and 1496 the islands of Gran Canaria, La Palma and Tenerife were conquered. On January 2, 1492, the kings entered the Alhambra in Granada, thus ending the Reconquest. The important figure of Gonzalo Fernández de Córdoba (nicknamed the Great Captain) will appear. In 1492 Christopher Columbus discovered the West Indies and in 1497 Melilla was taken. After the capture of the Nasrid kingdom of Granada for the Crown of Castile, foreign policy will turn towards the Mediterranean. Castilla will help Aragon with its armies in its problems with France, which will culminate in the recovery of Naples in 1504 for the Crown of Aragon. Later that same year, Queen Elizabeth died.

16th-17th centuries: from the Empire to the crisis

Regency Period

Queen Isabella had excluded her husband from the succession to the Crown of Castile, which passed into the hands of her daughter Juana (married to Felipe of Austria, nicknamed El Hermoso). But Isabel knew about the disease that her daughter suffered from (for which she was known as Juana la Loca) and appoints Fernando as regent in case Juana does not want or cannot understand their government . In the Concord of Salamanca (1505), the joint government of Felipe, Fernando and Juana herself was agreed. However, the bad relations between him (supported by the Castilian nobility) and his father-in-law, King Ferdinand the Catholic, make the latter renounce power in Castile to avoid an armed confrontation. By the Concordia de Villafáfila (1506), Fernando retires to Aragon and Felipe is proclaimed King of Castile. In 1506 Felipe I died and Fernando el Católico returned to the regency.

Fernando continues the expansion policy of both Crowns, Castile towards the Atlantic and Aragon towards the Mediterranean. In 1508 he conquered the Peñón de Vélez de la Gomera for Castilla, between 1509 and 1511 Orán, Bugía and Tripoli were conquered and he submitted to Algiers. In 1515 he takes Mazalquivir. When Gastón de Foix died, his inheritance rights to the kingdom of Navarre passed into the hands of Queen Germana de Foix, Ferdinand's wife. Using these presumed succession rights, the Treaty of Blois signed by the kings of Navarre with France in 1512, and with the help of the Beaumontese Navarrese, Fernando occupies the kingdom of Navarre with his troops, some 20,000 well-equipped soldiers under the orders of the Duke de Alba and in addition, Fernando also has the support of his son, the Archbishop of Zaragoza with more than 3000 men who will besiege Tudela, where there was strong resistance. The Courts of Aragon and the city of Zaragoza itself did not authorize it until early September, after the papal bull Pastor Ille Caelestis was proclaimed, and when there were few resistances left in the Kingdom. On the other hand, he did not inform the Cortes of Castilla, so they did not give him permission. In 1513, Ferdinand is recognized as King of Navarre by the Navarrese Cortes (attended only by Beaumonteses). Between 1512 and 1515 Navarre was part of the Crown of Aragon. Finally, in 1515 in the Cortes de Castilla meeting in Burgos the annexation of the territory to the Crown of Castile was accepted. No Navarrese attended this meeting.

On the death of Fernando in 1516, Cardinal Gonzalo Jiménez de Cisneros succeeded him as regent to pass the crowns of Navarre and Aragon to his grandson, son of Juana and Felipe: the future Carlos I

Charles I

Charles I receives the Crown of Castile, Aragon and the Empire due to a combination of dynastic marriages and premature death.

- From his father Philip (fallen in 1506) inherited the Netherlands

- When King Fernando the Catholic (his grandfather) died, he received the Crown of Aragon in 1517 and also that of Castile (together with America) as his mother was queen Juana unable to govern.

- And as a grandson of Maximilian, he received in 1519 the Holy Roman German Empire under the name of Charles V.

Charles I was not well received in Castile. Contributing to this was the fact that he was a foreign king (born in Ghent), and that even before his arrival in Castile, he granted important positions to Flemings and that Castilian money was used to finance his court. The Castilian nobility and the cities were close to an uprising to defend their rights. Many Castilians preferred his younger brother Fernando (raised in Castile) and in fact the Council of Castile is opposed to the idea of Carlos as King of Castile.

In the Castilian Cortes in Valladolid in 1518, a Walloon (Jean de Sauvage) was appointed president. This provoked angry protests in the Cortes, which rejected the presence of foreigners in their deliberations. Despite the threats, the Cortes (led by Juan de Zumel, Burgos' representative) resisted and got the king to swear to respect the laws of Castile, remove foreigners from important positions and learn to speak Castilian. Carlos, after his oath, gets a grant of 600,000 ducats.

Charles I is aware that he has many options to be emperor and he needs to prevail in the Crown of Castile and access its wealth for his imperial dream. Castile was one of the most dynamic, wealthy and advanced territories in Europe in the XVI century, and he began to realize that can be immersed in an empire. This, together with the lack of his promise by Carlos, causes hostility towards the new king to increase. In 1520 Cortes were convened in Toledo for another grant (the service), which the Cortes rejected. They are reconvened in Santiago with the same result. Finally they convene in La Coruña, a significant number of representatives are bribed, others are not allowed to enter, and they get the service approved. The representatives who voted in favor are attacked by the Castilian people and their houses burned. The Cortes will not be the only opposition that Carlos will encounter: when he left Castile in 1520, leaving his former tutor, Cardinal Adriano de Utrecht, as regent, the War of the Communities of Castile broke out. The comuneros were defeated in Villalar a year later (1521). After the defeat, the Cortes was reduced to a mere consultative body.[citation required]

The war in Navarre was reproduced several times in the years following the death of Fernando el Católico, due to the reconquest attempts of the Navarrese kings, aided by the kingdom of France. One of them as soon as Carlos I acceded to the throne, in 1516, which was soon stopped. The most important occurred in 1521, where, in addition to the entry of troops from the north, there was support from the Navarrese population (including the Beaumontese), with a general uprising that led to the expulsion of the army of Carlos I from all Navarrese territory.. Then Carlos I sent an army of 30,000 well-equipped men, which in a short time and after the bloody Battle of Noáin returned control of most of the Navarrese territory. Two later pockets of resistance still remained, in the Maya Castle in 1522 and in Fuenterrabía in 1524, as well as in Lower Navarre, where the incursions of Carlos I's army were unstable. Finally, in 1528, Carlos I would withdraw from the territory of Lower Navarre, unable to defend it effectively, and abandoning his claims over it, and without any formal treaty between the Kings of Navarre and Carlos I.

Imperial policy of Felipe II

Philip II followed the same policy as Carlos I. But unlike his father, he made Castile the center of his empire, centralizing his administration in Madrid. The rest of the states maintained their autonomy governed by viceroys.

Since Carlos I the tax burden of the empire fell mainly on Castile, and with Felipe II it quadrupled. During his reign, in addition to raising existing taxes, he introduced new ones, among them the toilet in 1567. That same year Felipe II ordered the proclamation of the Pragmática. This edict limited the religious, linguistic and cultural freedoms of the Moorish population, and provoked the Rebellion of the Alpujarras (1568-1571), which Juan de Austria reduced militarily.

Castilla went into recession in 1575, which caused the suspension of payments (the third of his reign). In 1590, the Servicio de Millones, a new tax on food, was approved in Parliament. This ended up ruining the Castilian cities and eliminated their feeble attempts at industrialization. In 1596 there was a new suspension of payments.

Reign of the Lesser Habsburgs

In the previous reigns, the posts in the institutions of the kingdoms were filled with people with studies, the administrators of Felipe II used to come from the universities of Alcalá and Salamanca. From Felipe III on, the nobles once again imposed their status to govern, as it was necessary to demonstrate cleanliness of blood. Religious persecution led Felipe III in 1609 to decree the Expulsion of the Moors.

Faced with the collapse of the Castilian treasury to maintain the hegemony of the Spanish Empire during the reign of Felipe IV, the Count-Duke of Olivares, the King's guardian from 1621 to 1643, tried to carry out a series of reforms. Among these is the Union of Arms, an attempt for each territory within the Hispanic Monarchy to contribute proportionally to its population in supporting the army, in order to alleviate the tax burden suffered by Castile, but this purpose not only failed, rather, it weakened the monarchy of Felipe IV. The Count-Duke lost royal favor and was succeeded by his nephew Luis de Haro as Philip IV's favorite between 1659 and 1665. His objective was to put an end to the internal conflicts raised by his predecessor (uprisings in Portugal, Catalonia and Andalusia) and achieve the peace in Europe.

After the death of Felipe IV in 1665 and before the inability of Carlos II to govern, economic lethargy and power struggles between the different valid ones followed. In 1668 the Spanish monarchy accepted the independence of Portugal in the Treaty of Lisbon (1668); Simultaneously, the incorporation of Ceuta to Castilla, which had chosen not to join the uprising and to remain faithful to Felipe IV, became effective. The death of Carlos II in 1700 without descendants causes the War of the Spanish Succession.

Minor territorial entities

In the Iberian Peninsula

- Kingdom of Galicia

- Principality of Asturias

- Kingdom of León

- Extremadura

- Kingdom of Castile

- Lord of Vizcaya

- Kingdom of Toledo

- Señorío de Molina

- Kingdom of Murcia

- Kingdom of Córdoba

- Kingdom of Jaen

- Kingdom of Seville

- Kingdom of Grenada

- Kingdom of Navarre

In Africa

- Ceuta

- Melilla

Overseas

- Kingdom of the Canary Islands

- Virtue of the Indias (1492-1535)

- Virtue of New Spain (from 1535)

- Virreinate of Peru (from 1542)

Contenido relacionado

History of Logic

GM-NAA I/O

Hittite laws

Donation of Pepin

History of optics