Casa Mila

The Casa Milà, popularly called “La Pedrera” (“quarry” in Catalan), is a modernist building designed by the architect Antoni Gaudí, built between the years 1906 and 1910 in the Eixample district of Barcelona, at number 92 Paseo de Gracia. The house was built at the request of the married couple Pedro Milá y Camps and Roser Segimon, and Gaudí had the collaboration of his assistants Josep Maria Jujol, Domingo Sugrañes, Francesc Quintana, Jaume Bayó, Juan Rubió, Enrique Nieto and José Canaleta, as well as the builder Josep Bayó i Font, who had worked with Gaudí on Casa Batlló. Since its opening to the public in 1987, it has received more than 20 million visits (approximately one million each year), making it one of the ten most visited places in Barcelona. In 2016 it received 1.2 million visitors, making it the eighth most visited monument in Spain.

Casa Milà is a reflection of Gaudí's artistic fullness: it belongs to his naturalist period (first decade of the 20th century), a period in which the architect perfected his personal style, drawing inspiration from the organic forms of nature, for which he which put into practice a whole series of new structural solutions originating from Gaudí's in-depth analysis of ruled geometry. To this the Catalan artist adds great creative freedom and an imaginative ornamental creation: starting from a certain baroque style, his works acquire great structural richness, shapes and volumes devoid of rationalist rigidity or any classical premise.

Since 2013, La Pedrera has been owned by the Fundación Catalunya-La Pedrera, which is in charge of organizing exhibitions, activities and visits.

History

Casa Milà is located on a corner of Paseo de Gracia with Provenza street, previously occupied by a villa that bordered the municipalities of Barcelona and Gracia, before the annexation of this villa to the city of Barcelona in 1897. The villa belonged to José Ferrer-Vidal y Soler, brother of Luis Ferrer-Vidal y Soler, founder of the Caja de Pensiones para la Vejez y de Ahorros de Cataluña y Baleares, and the purchase was formalized before a notary on June 9, 1905. The area was located in the Ensanche district of Barcelona, designed by Ildefonso Cerdá and approved in 1859, with a reticular system of residential blocks with cut corners, with the plan to build on two sides and dedicate the rest to gardens, this last point that finally was not carried out. With the Ensanche, Paseo de Gracia became one of the main arteries of the city, which is why it was chosen by the Catalan bourgeoisie to set up their residences, thanks to which this street grew rapidly and became a hub of construction where the best architects of Barcelona developed their work. It should be noted that Gaudí had built Casa Batlló (1904-1906) shortly before on Paseo de Gracia, and had previously carried out two other interventions that have now disappeared: the Gibert Pharmacy (1879) and the decoration of the Torino bar (1902).

In this context, Gaudí was commissioned to build a manor house by Pedro Milá y Camps, a wealthy businessman whose father, Pedro Milá y Pi, had made his fortune in the textile industry. Milà expanded the family business and diversified the sectors where he tried his luck, being for example the promoter of the La Monumental bullring. He also dedicated himself to politics, and was a deputy for the Catalan Solidarity. Mr. Milà was married to Roser Segimon, widow of José Guardiola Grau, an Indiano who had become rich in America with coffee plantations, whose fortune his wife inherited. Thus, the couple enjoyed a privileged position, a fact that they wanted to capture in a house with an innovative design and great luxury of detail. For this they bought the plot of Passeig de Gracia in 1905, and commissioned the project to Gaudí, then a renowned architect, who at that time was working on various projects at the same time: the Expiatory Temple of the Sagrada Familia (1883-1926), Torre Bellesguard (1900-1909), Park Güell (1900-1914), Casa Batlló (1904-1906) and the restoration of the Cathedral of Mallorca (1903-1914).

Milà's project was to build a large building, allocating the main floor for his own residence and the rest for rent, something common at the time. Likewise, the ground floor, on the outside, was used for shops, the first being a tailor's shop opened in 1928. On February 2, 1906, the plans were presented to the City Hall and a building permit was requested. The construction suffered various delays, since the building exceeded the height and width of what was established in the municipal ordinances, for which Mr. Milà was imposed several fines. In addition, Gaudí abandoned the direction of the work in 1909 due to disagreements with the Milàs regarding the interior decoration. The relationship between Gaudí and Milà cooled, and the architect had to take the promoter to court to collect his fees (105,000 pesetas), which he donated to the Jesuits. To make the payment, Mr. Milà had to mortgage the house.

From an administrative point of view, it also caused some controversy when in December 1907 the City Council stopped the works because a pillar occupied a part of the sidewalk without respecting the alignment of the facades. When the news was communicated to Gaudí, he responded with his usual ironic style:

Tell them that if they want to cut the pillar as if it were a cheese and in the remaining polished surface we will sculpt a legend that says: Cut by order of the City Council according to the plenary session of such date.

However, the suspension of the works was not respected and Gaudí continued with his work. On September 28, 1909, a new file was opened because it exceeded the planned height and exceeded the built volume by some 4,000 m³. The City Council demanded a fine of 100,000 pesetas (approximately 25% of the cost of the work) or demolish the attic and the roof. The controversy was resolved a year and a half later, on December 28, 1909, when the Ensanche Commission certified that it was a monumental building and that it was not required to strictly conform to municipal ordinances.

It is in the light of the fact that the building in question, whatever its destiny, has an artistic character that separates it from the other particular buildings, giving it special physiognomy, to which the work carried out mainly contributes by separating itself from the approved planes.

This solution greatly satisfied Gaudí, who asked for a copy of the resolution to keep. Finally, in 1910 the Milàs asked the City Council for permission to rent the apartments in the building, but it was not granted until October 1912, when Gaudí certified the completion of the works.

The construction process was related years later to the historian Joan Bassegoda by the builder, Josep Bayó: first the previous chalet was partially demolished, leaving a part of the structure as a construction shed, where Gaudí's assistants cleaned the sketches that the architect was giving them; then the land was lowered by 4 meters, to the depth necessary for the basement; When this was covered, the work workshop was moved there, and the rest of the chalet was demolished. The foundations were made with concrete made from Montjuïc stone gravel mixed with lime mortar, on which the pillars were raised, some made of cast iron and others made of brick —for which the bricks from the previous chalet were used. Once the basement was finished, the construction of the rest of the floors proceeded, while the façade —which is self-supporting and independent from the rest of the building— was projected, through some plaster models that were modeled by the plasterer Joan Bertran under the supervision of direct from Gaudí; This model was later cut up and taken as a model to the work, where the stonecutters faithfully followed its structure. A system of girders and iron beams arranged in the form of a Catalan vault was used on all floors, joined by rivets and screws, without the need for welding. The façade was covered with stones forming wavy-shaped arches, which were later retouched by the stonecutters until they achieved the shape desired by Gaudí. Finally, the attic was built, designed independently from the rest of the building, with a system of brick catenary arches, and the roof was placed above, in a staggered manner given the different heights of the attic arches.

Its owner presented it to the annual competition for artistic buildings of the Barcelona City Council, where that year two works by Enric Sagnier (calle Mallorca, 264 and Córcega with Diagonal) were competing: the Casa Gustà, which was a private home of the architect Jaume Gustà, and the Pérez Samanillo House, the work of Joan Josep Hervàs. Although the most spectacular and clearly favorite was Casa Milà, the jury ruled it out, stating that "despite the façades being finished, there is still a long way to go before it is fully completed, finalized and in a perfect state of appreciation." The 1910 winner was that of Pérez Samanillo, the current headquarters of the Círculo Ecuestre.

During the Spanish civil war, La Pedrera was occupied by the PSUC, whose general secretary, Joan Comorera, installed himself on the main floor. The Milàs, who were spending the summer in Blanes at the outbreak of the war, went over to the rebel side, and returned home once the war was over. Pedro Milá died in 1940, and a few years later, in 1946, her wife sold the property to CIPSA Real Estate (Compañía Inmobiliaria Provenza, SA), although she continued to live in her apartment until her death in 1964..

La Pedrera has suffered several vicissitudes: in 1927 Roser Segimon ordered the builder Josep Bayó to remodel the interior of the main floor, and the decoration carried out by Gaudí was lost; in 1932 the coal bunkers were transformed into shops, eliminating the iron bars that separated the semi-basement and the street; in 1954 CIPSA Real Estate built thirteen apartments in the attic, by the architect Francisco Juan Barba Corsini; in 1966 the main floor was transformed into offices, with the signature of Leopoldo Gil Nebot; between 1971 and 1975 a first restoration was carried out by José Antonio Comas de Mendoza. In 1986, it was acquired by Caixa de Catalunya, which has carried out continuous conservation and restoration works (1987-1996, under the responsibility of José Emilio Hernández Cros and Rafael Villa) and keeps it open to the public for visits, for which you can enter in the houses on the fourth floor, the attic and the terrace. The other floors are occupied by offices or still by some resident families.

Casa Milà was declared a National Historic-Artistic Monument in 1969, and in 1984 Unesco included it in the "Works of Antoni Gaudí" World Heritage Site, along with Palau Güell, Park Güell and the Crypt of Colonia Güell.

Description

The building was built on a plot measuring 34 by 56 meters, with a surface area of 1,835 m². It has six floors articulated around two interior patios, one circular and the other oval, plus a basement, an attic and a roof terrace. This structure houses two attached and independent buildings, each one with its own access door and its own patio, which are connected only on the ground floor. However, the façade presents a unitary structure common to both buildings. The load-bearing structure is made up of solid brick and stone columns. Dividing walls have no structural function, so their design varies from one floor to another. The interior structure of pillars and girders connects with the stone exterior by means of curved metal beams along the entire perimeter of each floor.

The basement, where a garage is located, contains a large iron pillar from which several equally iron beams start, supporting the circular patio, located immediately above. The façade does not fulfill a structural function either, but rather as a cladding, so that its design and ornamentation present marked creative freedom, with undulating shapes that evoke the ocean waves and generate different lighting sensations depending on the time of day. The balconies are made of wrought iron, decorated with abstract and phytomorphic motifs. Gaudí used a type of hexagonal ceramic tiles (known as Gaudí tiles) with again marine motifs (algae, starfish, shells), made by the Escofet company, to pave the service rooms of Casa Milà (the architect had initially designed to pave the floors of the rehabilitation of Casa Batlló). This tile was later chosen to pave Paseo de Gracia in Barcelona.

The ensemble, due to its innovation, is a typical Gaudí work in which the geometric lines are only straight lines forming curved planes. Its entire façade is made of limestone, except for the upper part, which is covered with white tiles, the combination of which evokes a snow-capped mountain. On the roof there are large stairwells topped with the Gaudinian cross with four arms, and chimneys covered with ceramic fragments, with the appearance of warrior heads protected by helmets. It is worth noting the beauty of the wrought iron on its balconies, which simulate climbing plants, the work of the brothers Lluís and Josep Badia i Miarnau.

Of organic shapes, Casa Milà undoubtedly evokes nature: various scholars have perceived shapes in La Pedrera that recall the Fra Guerau cliffs in the Prades mountain range near Reus, the Pareis torrent in northern Mallorca or Sant Miquel del Fai in Bigues i Riells, all of them places visited by Gaudí.

Gaudí had assigned a high religious symbolism to La Pedrera: on the upper cornice, which is wavy in shape, it has sculpted rosebuds with inscriptions of the Ave Maria in Latin (Ave Gratia M plena, Dominus tecum). In addition, according to the original project, the façade would have been topped by a sculptural group of stone, metal and glass with the Virgin of the Rosary with the Child Jesus in her arms, surrounded by the archangels Michael —with a sword defeating Satan, coiled in a globe of the world located at the feet of the Virgin—and Gabriel —with a lily symbol of purity—, 4 meters high. A sketch was made by the sculptor Carles Mani, first in clay on a scale 1: 10 and then in plaster in its final size, which was ready to be cast in bronze in March 1909; but due to the events of the Tragic Week of 1909 the project was abandoned.

The interior decoration was carried out by Josep Maria Jujol and the painters Aleix Clapés, Iu Pascual, Xavier Nogués and Teresa Lostau. Carles Mani and Joan Matamala, authors of the embossed inscriptions on the façade, as well as the columns on the main floor and other decorative elements, worked on the sculptural field. Ornamental marine details are often found, such as the false plaster ceilings that simulate sea waves, as well as octopuses, shells and marine flora. Pedro Milá entrusted the direction of the pictorial decoration to Aleix Clapés, the reason for the definitive break between Gaudí and the Milà couple, since the architect had commissioned the decoration to the Manresan painter Lluís Morell i Cornet —who came to do some paintings in the walls of the service stairs—which, however, was not to the liking of the Milàs. For this reason, Gaudí abandoned the direction of the project, which was completed by his assistants.

Facade

Casa Milà has three façades, one on Paseo de Gracia, another on Provenza street, and another that has a chamfer, following the usual scheme of the Ensanche projected by Cerdà. However, all three present a formal and stylistic continuity that, due to its sinuous and wavy shape, looks like a rock shaped by the waves of the sea. The set of inlets and outlets gives the whole a dynamism that gives it the sensation of being in motion, while creating a constantly changing play of light and shadow depending on the time of day or the position of the viewer. In addition to the undulating shape of the façade walls, the presence of 33 wrought iron balconies, with an original shape similar to seaweed, turn the complex into a large, almost sculptural work. Most of the railings have a rather abstract shape, although there are some specific details such as a dove, a theater mask, a six-pointed star, various flowers and the Catalan coat of arms.

The three facades, 30 meters high, contain 150 windows, with different structural solutions, shapes and sizes, the lower ones being larger and the upper ones smaller, which receive more light. The stone used for its construction has two sources, one harder, from Garraf, in the lower part; and another less hard, from Villafranca del Panadés, at the top. Both give a creamy white finish, which generates different shades depending on the incident light, and they are finished with a rough texture, which provides an organic appearance.

- Facade of the Paseo de Gracia: facing southwest, it has 21.15 meters long and 630 m2 of surface, with nine balconies overlooking the street. It is crowned with the word Ave of the Hail Mary, with a relief of lilies, symbol of the purity of the Virgin. She's the only one with no access door. The part belonging to this facade of the ground floor was intended for charcoal, and originally had bars, which were withdrawn when transformed into commercial stores.

- Facade of the chaflan: it is 20,10 meters long, and as the central one is the best known of the building. It houses one of the two gates of access, flanked by two large columns (usually nicknamed "ephant ducks") that hold the main floor tribune, that of the Milà marriage. Apparently, for the set of door and tribune Gaudí was inspired by the work of a Baroque architect from Madrid, Pedro de Ribera. The roof of the tribune has a skylight to provide light, under which is a sculpted shell. At the top of the facade is a rose in relief, and the initial M de María, which would have been the basis of the sculpture of Mary and the archangels that were finally not placed. On the two sides of the chaflan are at the top of the words Gratia and Full of the Ave Maria.

- Provenza Street Facade: it has 43,35 meters long, so it is the most extensive, and it has an access door to the building. Orientated to the southeast, it receives light almost all day, so Gaudí designed it with more ripples than on the other two facades, as well as more outstanding balconies, to create more shade. At the top are the words Dominus and Tecum of the Ave Maria.

Along with these façades, it is worth mentioning the rear façade, which overlooks the inner courtyard of the block formed by Paseo de Gracia and Provenza, Roussillon and Pau Claris streets, not visible to the general public, since they only have access the neighbors. It is 25 meters long, with an area of 800 m². More sober than the main façade, it presents, however, the same wave shape, with a gap between the different floors that form inlets and outlets, emulating the sea waves, with large terraces with iron railings with a light diamond-shaped design., which allow the passage of light. This façade is made with a reddish-brown stuccoed cement and lime coating.

Inside

The interior of Casa Milà is functionally designed for fluid communication between the various parts of the building. To do this, the ground floor has two entrances with vestibules that connect the exterior and interior, and that connect with the two light wells, also favoring internal transit between the two areas of the building. The two wide portals allow the passage of vehicles, which after the entrance halls can access the lower garage through ramps that lead to the basement. For access to the houses, Gaudí prioritized the use of elevators, reserving the stairs as auxiliary access and for common services. However, for access to the main floor, he placed two large staircases, decorated with mural paintings.

The two entrance doors are made of wrought iron and glass, in such a way that they act both as a door and as a security gate. Its design is organic, with a series of structures of different shapes that can recall various designs made by nature, such as turtle shells, butterfly wings or cellular tissues. Its wide and diaphanous structure allows light to pass through easily, and profusely illuminates the interior halls. The portals give access to the two vestibules, one on Paseo de Gracia and the other on Provenza street. These vestibules give access to both the garage and the upper floors, and as they are designed for the passage of vehicular traffic, they are surrounded by a pedestrian sidewalk. The largest is the one on Paseo de Gracia (60 m²), which has a wavy ceiling, similar to that of a cavern. The one on Provenza street is similar in design, although smaller (44 m²), and presents as a singularity a sentry box for the doorman, made with a fine iron structure and glass carved with floral motifs. One of the most outstanding elements of the halls is the decoration with mural paintings, made by Aleix Clapés with ornamental motifs and themes of mythological inspiration, such as some scenes from The Metamorphoses by Ovid, for which inspired by some tapestries in the Royal Palace of Madrid. Other themes are also included, such as the seven deadly sins and various episodes from Life is a dream, by Pedro Calderón de la Barca. These paintings were restored between 1991 and 1992 by Gianluigi Colalucci, head of restoration of the Vatican Museums and previously in charge of the restoration of the Sistine Chapel.

- Paintings of Aleix Clapés

Access to the houses is articulated through two large light wells, which allow ample lighting and ventilation for all floors. Thus, the internal face of the floors presents a new façade with large windows and iron railings, with a system of cylindrical columns on the first two floors, replaced by plastered masonry on the upper floors. The Paseo de Gracia patio is cylindrical in shape, with a surface area of 90 m², while the Provenza patio has an elliptical shape, with 150 m². It is worth noting the decoration of the walls, which are painted in shades of ocher and yellow, and have some murals with intense colors, with various designs inspired by floral motifs and Flemish tapestries, mostly made by Xavier Nogués.

The apartment structure of Casa Milà starts from a basement used as a garage and storage room, which is accessed from the entrance halls by helical-shaped ramps, which cover a drop of 4.70 metres. It presents a structure of 90 stone, iron and brick columns, which support the building. This floor also contained the engine room for heating, as well as various common service areas. The neighbors accessed by auxiliary stairs, each one having a garage space and a storage room. After a rehabilitation carried out in 1994, the basement became an auditorium and a multipurpose room. Between the basement and the ground floor there is a semi-basement originally intended for coal bunkers, but which was later occupied by shops, for which the bars were removed of iron installed according to Gaudí's project. In this semi-basement there was also a small tunnel that surrounded the entire building and where the service pipes, gas pipes and electrical cables were located.

The apartment floors were designed by Gaudí in such a way that they could be easily adapted to the needs of the tenants, since by not having load-bearing walls the spaces are interchangeable and adaptable. Thus, all the floors and almost all the floors present different structures, which have evolved over time: for example, the main floor, the home of the Milà couple, was later an office, then a bingo hall and is currently a room of exhibitions. This house, the main one in the building, had 1,323 m², with access from both Paseo de Gracia and Calle Provenza, via elevator or two wide stairs that start from the entrance hall. It had more than 35 spaces for various uses, including the hall, an oratory, a reception room, Mr. Milà's office, the dining room and the master bedroom; some rooms received special names, such as the "purple room" or the "Chinese room". It is worth noting the different flooring designed by Gaudí according to their function: stone slabs from La Cenia for corridors and halls, parquet for living rooms and rooms, and hydraulic tiles for kitchens and bathrooms.

The decoration of the main house was one of the most luxurious and detailed in the building, by Josep Maria Jujol, who designed the furniture and various decorative elements, as well as some details in relief on columns and ceilings, always under the Gaudi's supervision. A pillar stands out with the Latin inscription charitas (charity), together with the Catalan words perdona (forgive) and oblida (forget), wrapped of various elements, such as a rose, a cross, a juvenile fish, a jellyfish, a lotus flower, an egg and a crowned M (for Mary); likewise, the i of oblida is shaped like a spermatozoon. In the same column, below, we read tot lo bé creu ("all good believes"), and in the o of lo a shell appears. In another column there is a lute, in another a harp, and in another a carrier pigeon and a table set for a banquet. In the ceilings and moldings, made of plaster, Jujol made various abstract or of naturalistic inspiration —such as marine undulations—, as well as various figures, symbols and inscriptions, such as the M for María, the phrase encara som lliures ("we are still free") or various lines of poems and songs popular Catalan. The owner, Roser Segimon, did not like this decoration, so she had it covered with plaster after Gaudí's death in 1926.

- Example of modernist floor of the Pedrera

The rest of the houses, intended for rent, were designed by Gaudí with the same care, for which he took care of every last detail and intervened in numerous cases in decorative elements and furniture. In general, the living rooms and bedrooms of each house face the street, while the service areas face the interior patios. On the first floor there are three houses of about 440 m² each; in the second and third there are four houses, one facing Paseo de Gracia, another facing the chamfer and two facing Provenza street; and in the fourth there are three houses, one that occupies the area of Paseo de Gracia and the chamfer, and two corresponding to Provenza street. Gaudí included for all of them all the advances and comforts for the time, such as electric light, heating and hot water; In addition, each house had a garage space and a storage room in the basement and a laundry room in the attic. The architect took maximum care of all the details, especially doors and windows, designed with a fully modernist ornamental style, as dictated by the stylistic canons of the time. Typically, these designs were organically inspired, such as raindrops, swirls, jellyfish, starfish, seaweed, and flowers. Another outstanding element are the plaster moldings in the door frames and in the interior arches of the houses, with various original designs with organic or abstract shapes. Gaudí even designed the doorknobs, made of bronze with again innovative and original designs, with almost sculptural shapes. He also produced numerous furniture designs, some of which can be seen on the building's show floor.

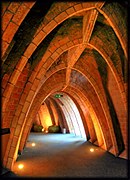

The top floor is the attic, which Gaudí conceived independently from the rest of the building, with an original structure that is both plastic and functional. This 800 m² floor housed the laundry rooms and other service areas, and at the same time acted as a thermal regulator, insulating the building from extreme temperatures, both in winter and summer. For this, the architect was inspired by the typical attic of the Catalan farmhouse, but with a new design based on parabolic arches, which in a succession of 270 brick arches create a self-supporting structure that does not need columns or load-bearing walls, and that achieve an open space that creates a corridor along the entire length of the building. These arches meet at the ceiling in a kind of spine that recalls the skeleton of some animal or the structure of a ship arranged upside down. On the outside, this attic is located a few meters further in than the line of the façade, and is furrowed by two lines of small windows, the lower ones a little larger than the upper ones. In the space between the attic and the façade there is a narrow walkway that encircles the building, along which there are four small domes with a parabolic profile. The attic was remodeled in 1953 by the architect Francisco Barba Corsini, who created thirteen apartments for rent, with a modern aesthetic and far removed from the Gaudinian project. However, after the acquisition of the building by Caixa Catalunya, in 1996 it was restored, returning it to the original design drawn up by Gaudí, and currently houses the Espai Gaudí (Gaudi Space), an exhibition on the life and work of of the architect, with models and audiovisual material of the main innovations carried out by the Catalan architect.

Rooftop

The building is crowned by a roof located on the attic, where Gaudí placed the stairwells, chimneys and ventilation towers, which due to their original shapes and innovative design create an authentic outdoor sculpture garden. The terrace is made up of several sections of different volumes and levels, whose offsets are connected by small flights of stairs, and which create a space of singular originality, which is both functional and aesthetic, two of the key premises of the architect. These unevenness of the roof are due to the different height of the attic arches, which generates a terrace with sinuous shapes that, together with the fantastic cut design of the vertical elements that arise there, generates a singular and original space, which has provoked many different interpretations by writers, historians and art critics: George Collins, for example, called it Wonderland ("wonderland").

On the roof there are a total of 30 chimneys, two ventilation towers and six stairwells, designed with different stylistic solutions. The stair exits start from the attic through cylindrical bodies that house spiral staircases, and that on the roof become small conical towers, up to 7.80 meters high, built in brick plastered with lime mortar., with a trencadís cladding —the original design made up of ceramic pieces that Gaudí had already used in several of his works, such as the continuous bench in Park Güell— the four facing the street, and with an ocher stucco finish on the two that face the interior of the block. In turn, the two most visible from the street —those with the chamfer— present a helical undulation on their trunk, while the rest have a bell-shaped body. Finally, all the stair exits are topped with the typical Gaudinian cross with four arms, although with a different design for each tower.

The ventilation towers are located on the rear façade facing the interior of the block, and are the exits for the ventilation ducts that start from the basement. They are made of brick plastered with yellow mortar, and have different designs: one is 5.40 meters high, with a hexagonal shape similar to a covered cup, perforated with two oval-shaped holes; the other, 5.60 meters high, has an original shape of organic undulations, similar to several superimposed masks, like several Moebius strips with holes in their central part. The abstract forms of these towers have been considered by many scholars as an antecedent of the abstract sculpture of the XX century. Salvador Dalí was a great admirer of these towers, with which he was photographed in 1951.

Lastly, the chimneys are one of the most famous and unique elements of the roof, and the one that has generated all kinds of speculations and hypotheses about their origin and symbolism. There are a total of 30 fireplaces, arranged in groups or individually, and scattered along the entire length of the terrace. Built in brick plastered with ocher-colored mortar, they have a body that rotates on itself in a helical shape, and topped with a small dome that, in most cases, has a shape similar to a warrior's helmet, although there are a few with different design, like some that look like the top of a tree, made with bits of green cava bottles. Likewise, in one of the chimneys Gaudí placed a heart that points towards Reus, his birthplace, while on the other side a heart and a teardrop point towards the Sagrada Familia, a fact that some experts interpret as a sign of sadness for not being able to see it finished; some other chimneys have crosses, X letters and various other signs of Gaudí's enigmatic symbolic universe. The shape of the chimneys has been reproduced in numerous elements related to Gaudí, such as the Roman soldiers in the Veronica group located on the Passion façade of the Sagrada Família, which the sculptor Josep Maria Subirachs created in homage to the architect. The film director George Lucas was also inspired by them for the helmets of the imperial soldiers and the evil Darth Vader in the Star Wars saga. Likewise, this iconographic element was chosen to make the statuettes of the Gaudí Awards, which are given annually by the Catalan Film Academy, and which consist of 35 cm high bronze figures, designed by Montserrat Ribé based on the Gaudinian forms present on the roof of La Pedrera.

Symbolic interpretation

The philosopher and writer Josep Maria Carandell offers in his work La Pedrera, cosmos de Gaudí a symbolic interpretation of the roof of Casa Milà based on religious, cosmogonic and literary concepts. For this author, the roof would be an auto sacramental (a dramatic work in celebration of Corpus Christi), a staging of the origin of life and the family sublimated by divine revelation. According to this hypothesis, the theatrical character of the terrace would be originated by two dramatic works, Life is a dream by Pedro Calderón de la Barca —as in the lobby of the building— and Hamlet by William Shakespeare, while the presence of Ovid's Metamorphoses would also continue, due to the changing and sinuous appearance of the roof. In Catalonia, the presence in Corpus Christi processions of giants and big heads, or animal figures such as dragons and vipers is traditional, and that would be Gaudí's intention for the rooftop of La Pedrera. Thus, the stair exits would be gigantic, each of which would assume a role in the sacramental procession: the main ones, located on the chamfer, would be the Fathers, in the shape of a dragon coiled in itself, the one on the right being the Mother, who is both mother nature, the mother of the family and the personification of the Virgin Mary and, allegorically, of Life, while the one on the left is the Father, identified with God the Creator and as an allegory of Power; the others would be the children, in two pairs, symbolized by the windows placed at their feet in a triangular fashion, the male ones facing up and the female ones facing down, the one on Paseo de Gracia being the "warrior son", the good and heroic one, who it corresponds with Saint Michael (or Saint George), or with Segismundo, the protagonist of Life is a dream, while ultimately it would be Jesus and, allegorically, Wisdom; The one facing the neighborhood courtyard is the "skeptical son", evidenced by being naked (he does not have the trencadís coating that the other figures have), and who would correspond to Hamlet, the doubtful and irresolute character; his equivalent, equally undressed , is the "crazy daughter", which corresponds to Shakespeare's Ofelia or Calderon's Rosaura; and the one on Calle Provenza is the "sensible daughter", whose virtues are assumed by Estrella, the infanta from Life is a dream, as an allegory of Love and the Holy Spirit (as demonstrated by its three-dimensional shape). entwined doves). Finally, the two ventilation towers are identified by Carandell with the King and Queen, the first being the one in the shape of a mask, which would correspond to Claudio in Shakespeare's work or Basilio in Calderón's; and the second, cup-shaped, would be Gertrude, the mother of Hamlet, the adulterous queen, who would personify Lasciviousness —hence the openings in the form of a female womb.

Criticism and controversy

The building did not respect any standard of conventional style, for which it received a lot of criticism. To begin with, the name "La Pedrera" is in fact a nickname assigned by citizens who censored its heterodoxy. The satirical magazines were the main space for the dissemination of criticism: Junceda presented it in a joke as an "Easter monkey"; Ismael Smith insinuated that it had suffered an earthquake like Messina; Picarol assimilated it to an imaginary Wagnerian Valhalla or as an anti-war defense from the Moroccan war, or as a hangar for airships. In his Diary Joaquim Renart made a joke about the difficulty of putting hangings on wrought-iron balconies. There is also a famous anecdote that tells that when the French politician Georges Clemenceau came to Barcelona to give a conference, when he saw La Pedrera he ran away without even giving his speech, terrified that people could live in such a place.

However, it also had defenders, one of the first being Salvador Dalí, who claimed it in the magazine Minotaure in 1933, in an article entitled De la beauté terrifiante et edible de l& #39;architecture modern style. Later, it was praised by figures such as Le Corbusier, Nikolaus Pevsner, George Collins, Roberto Pane or Alexandre Cirici.

Contenido relacionado

Gladiator

Annex: Goya Award for Best Director

Musical instrument