Carlism

Carlismo is a Spanish political movement of a traditionalist and legitimist monarchical nature derived from Fernandino realism that emerged during the first half of the 19th century in opposition to liberalism, parliamentarism and secularism. It claims the establishment of an alternative branch of the Bourbon dynasty on the Spanish throne and the so-called social reign of Jesus Christ. In its origins it advocated a return to the Old Regime, and later developed a political doctrine inspired by the Spanish tradition and medieval Christianity.

Throughout its history, the political organization of Carlism was known as the Carlist Party, the Catholic-Monarchical Communion, the Jaimista Party, the Legitimist Communion or the Traditionalist Communion, among other names. Fighting liberalism, he made a banner for the defense of the Catholic religion, Spain and the traditional monarchy summed up in his motto "God, Homeland, King", with the late addition of "Fueros".

As a movement of extraordinary prolongation in time, Carlism was an important force in Spanish politics and the press from 1833 until the end of the Franco regime in the 1970s. It was the protagonist of numerous wars and attempts in the XIX, among which the civil wars of 1833-1840 and 1872-1876 stand out. During the Revolutionary Sexennium, the Alfonsine Restoration and the Second Republic, he acted in parliamentary politics and took part in the conspiracy against the Republic and in the Spanish civil war of 1936-1939 with the Requeté militia.

After the Unification Decree of 1937, the Traditionalist Communion was officially integrated into the single party, Falange Española Tradicionalista y de las JONS, and its former militants were considered one of the "families" of Francoism, some Carlist political positions. Others, on the other hand, acted in a semi-clandestine situation outside the single party, with periods of opposition and collaboration with the regime.

Following the expulsion from Spain of the Borbón-Parma family in 1968 after having tried to be recognized as successor to the Crown of Spain by General Franco, Carlism divided into two clearly differentiated sectors: one of them, a minority and sponsored by Prince Carlos Hugo de Borbón-Parma, his sister María Teresa and a part of the Carlist student group, claimed a renewal of the movement, claiming democratic freedoms, federalism and self-management socialism, and took the name Carlist Party; The majority sector, in favor of continuing with the traditionalist doctrine, was largely demobilized and atomized into various groups (some of which had previously split from Javierismo) that would constitute the Spanish National Union, Traditionalist Communion, Catholic Monarchical Communion and Carlist Union, among others.

The ideological change led by Carlos Hugo, the divisions of the 1970s and the electoral failure in the first democratic elections in the Transition, meant that Carlism fell into decline. In the fragmentation of Carlism, the attitude towards the new ideas of Catholic thought that emerged after the Second Vatican Council, especially after the conciliar declaration Dignitatis humanae in favor of religious freedom.[citation required ]

Doctrine

According to the General Zumalacárregui Center for Historical and Political Studies, Carlism is a political movement articulated around three fundamental facets: a dynastic flag, historical continuity and a legal-political doctrine.

The Carlists formed the traditional wing of Spanish society at the time, encompassing the so-called "apostolic" or traditionalists and, above all, the anti-liberal reaction. The fight between the supporters of Isabel II, daughter of Fernando VII, and the infante Carlos María Isidro, brother of the king, was really a fight between two political and social conceptions. On the one hand, the defenders of the Old Regime (the Church, the aristocracy, etc.) and on the other, the supporters of the liberal reforms promoted by the bourgeoisie, which emerged as a consequence of the French Revolution, which had begun to reorganize society in the political sphere. Thus, Carlism had less impact in large cities, being a predominantly rural movement.[citation required]

Another aspect of the dispute took place in the religious field, with the desire of the Carlists to preserve the catholicity of the laws and institutions typical of the Spanish political tradition, and especially of the so-called Catholic unity of Spain. The Liberals began a process of confiscations (Madoz and Mendizábal) that deprived the monasteries of cultivated land, to sell them at public auction to the great fortunes, filling the public coffers of the state and some liberal politicians. They also began the burning of convents and the murder of religious in 1834 and deprived the peasantry of the communal lands of the Town Halls, with which they maintained a subsistence economy, forcing them to join the ranks of an incipient proletariat that, a few years later, Later, it served as a ferment for the socialist and anarchist revolutions.

Thus, Spain was reformed in the political, religious and social fields very profoundly. As a consequence of this, although Carlism had been demobilized after the Vergara Agreement in 1839, the reaction of the traditionalist sectors, defenders of the old union order, and of the Church, continued before the policy of the new liberal governments, provoking the Carlists. some uprisings, especially in Catalonia. In this context, after the revolution of 1868 that established democracy with male suffrage and freedom of worship, numerous Elizabethan monarchists would go on to defend the Carlist cause, reviving the movement again throughout Spain.

In addition, the supporters of the pretender Carlos María Isidro encouraged the continuation of the Basque and Navarrese privileges in the territories of the rebellious areas of the north, where the Carlist uprising triumphed since the foral legislation had allowed the Royalist Volunteers not to be purged there as in the rest of Spain, since it left the sub-inspection of the bodies in the hands of the respective councils. However, where Carlism arose for the first time was in Castilla and not in the foral provinces, and there are discrepancies between historians regarding whether the defense of the fueros was a characteristic feature of Carlism from its origin or if it manifested itself already started the first Carlist war. After the revolution of 1868, a manifesto of the pretender Carlos VII (grandson of Carlos María Isidro), written by the Carlist leader Antonio Aparisi y Guijarro, would affirm the will of the pretender to extend the foral regime of the Basque provinces to all of Spain. In 1872, during the third Carlist war, Don Carlos assured in another manifesto that he annulled the Nueva Planta Decrees promulgated by his ancestor Felipe V, thus returning the privileges to Catalonia, Aragon and Valencia.

This is how the Carlist ideology was formed: dynastic legitimacy, Catholic unity, federative and missionary monarchy —in the words of Francisco Elías de Tejada—, with regional regional rights. His motto was "God, Country, King."

According to Melchor Ferrer, although Carlism was born in 1833 to defend absolutism, he later disassociated himself from it and developed a policy of defense of the medieval tradition influenced by the thought of Jaime Balmes.

In 1935, an album published on the occasion of the hundred years of Carlism's history, compiled by the publicist Juan María Roma, defined Carlism not as "the mere unconditional and absolute return to the past" but as "the restoration of the old Purified regime of the imperfections inherent to times that were, cured of the vices introduced into it by possible errors of time and completed or perfected with the good and useful of the present times recognized as such in the touchstone of experience. He also affirmed that Carlism was "the restoration of the monarchy that made Spain the greatest and most glorious nation in the world" and that it was not the form, "but the spirit, the background of the tradition", which should be restored.

Regarding representation in Cortes, Carlism called for corporate representation, not individualistic like that of the parliamentary regime. The traditional courts should be the representation of the classes, unions and corporations, with an imperative mandate. The Carlists defended the expansion of the foral principle to all of Spain and the subordination of political power to the authority of the Church in matters related to religion and morality.

They defined liberalism as the «enemy of the Fatherland» and accused it of having sacrificed the «Catholic unity of Spain» to satisfy the interests of international Freemasonry; of having deprived peoples of their traditional liberties to give them "liberties of perdition"; of having replaced kings who ruled with kings who only reigned and of having broken the unity of the Spanish people by dividing it into parties that subordinated the interest of the country to that of their own side.

According to its supporters, the three civil wars waged by Carlism in the XIX century would have been the continuation of the war of Spanish Independence, and the liberals would have been the continuators of the work of the afrancesados (considered therefore enemies of the homeland) and the promoters of the loss of authority and "true freedom". Both the lack of religiosity and good customs as well as the collapse of the estate, agriculture, industry and commerce, as well as the loss of the colonies, would have been the fault of liberalism.

Although during the Elizabethan reign the newspaper La Esperanza, directed by Pedro de la Hoz, would act as an unofficial doctrinal organ of Carlism, Carlist thought would take shape especially after the Revolution of 1868 and the passage from the so-called "neo-Catholics" to the Carlist ranks within the Monarchical Catholic Communion. The former Elizabethan deputy Antonio Aparisi y Guijarro, whose thought was inspired by the work of Donoso Cortés and Jaime Balmes, collaborated with the suitor Carlos VII and would become one of the main Carlist theorists, along with other thinkers and journalists such as Gabino Tejado or Francisco Navarro Villoslada.

Juan Vázquez de Mella, nicknamed «the Word of Tradition», would become at the beginning of the XX century the ideologue par excellence of Carlism. His work was reflected in his speeches, generally delivered in the Cortes, and in his articles published in El Correo Español and other traditionalist newspapers. Other notable Carlist authors of the Restoration were Luis María de Llauder, Leandro Herrero, Benigno Bolaños, Miguel Fernández Peñaflor, Manuel Polo y Peyrolón and Enrique Gil Robles, among many others.

The foral issue

The question of fueros was very important in the history of Carlism, since they had allowed Carlism to triumph in the Basque provinces and Navarra, where the Royalist Volunteers could not be purged from the Army as in the rest of Spain, and they gained significance in other regions, especially during the Third Carlist War, when the pretender Carlos VII proclaimed that he was restoring the privileges of Catalonia, Valencia and Aragon. The arrival of the Bourbons and the triumph of Felipe V had meant the suppression of the privileges of the crown of Aragon, although the Basques and Navarrese remained.

The Basque-Navarrese foral system granted certain privileges. In the economic field, for example, the internal customs allowed the free importation of products, and, in the political sphere, the foral pass achieved or denied validity to the royal provisions, limiting the authority of the king. After the first Carlist war, the liberal government did not abolish the fueros of the Basque Country and Navarra, since the Vergara agreement obliged the liberal state to respect them as long as they did not come into conflict with the new constitutional order. They would finally be suppressed after the third Carlist war, obtaining in return in 1878 the Basque-Navarre provinces the so-called Economic Agreement.

Although very soon there were those who saw the defense of the fueros as the motivation for the Carlist uprising in the north, in 1845 the Navarrese Juan Antonio de Zaratiegui, assistant and secretary of General Zumalacárregui, wrote that it was an error to affirm that the Navarrese had took up arms in the first Carlist war to defend their fueros, since in 1833 they were fully in force. In his work Vida y hechos de don Tomás de Zumalacárregui, Zaratiegui claimed to be able to demonstrate that the uprising in Navarre had no other purpose than the defense of the rights to the Spanish crown of the infant Carlos María Isidro and protested against those who held the opposite.

Nevertheless, after the triumph of the Carlist uprising in most of the Basque-Navarrese territory, on November 30, 1833, General Castañón, interim captain general of the Basque Provinces, sided from Tolosa suspending the privileges and privileges of Álava and Vizcaya, except for the part of Guipúzcoa that had remained loyal to the regent María Cristina. Although on May 19, 1837 Espartero proclaimed in Hernani that the government had never had the intention of abolishing the fueros, in September of the same year the Christian authorities made the provincial councils cease, replacing them with provincial councils, which earned the supporters of Don Carlos to demonstrate to the Basques that the intention of the liberals was to end their privileges, of which they had already been warned, and to commit them more to the defense of their cause. Taking advantage of this state of mind, the Carlists tried to unite both issues, the foral and dynastic, and made the suitor swear the privileges under the tree of Guernica, promising to respect them and keep them in the most exact observance of it.

Even so, according to the fuero writer José María Angulo y de la Hormaza, it would be precisely the desire to preserve the fueros that would bring about the end of the first Carlist war in the north. For this purpose, the notary public José Antonio Muñagorri popularized, with the cooperation of the government, the motto of «Peace and Jurisdictions», which would facilitate the conclusion of the conflict through the Vergara Agreement signed by General Maroto (considered the great traitor of the Carlist cause).

Since the Basque-Navarrese fueros, which would remain in force until the Revolutionary Six-year period, sanctioned Catholic unity in those provinces —since they only allowed old Christians to live in them—, during this period Carlism began to make a banner of fuerism as an essential part of his political doctrine, showing that freedom of worship, civil marriage and other laws of the revolutionary government were a counter-law, as the Biscayan traditionalist Arístides de Artiñano would denounce.

According to Angulo and de la Hormaza, the fueros were not, in fact, the cause of the triumph of the Carlist uprising for the second time in 1872 in the Basque Provinces and Navarre, but anti-clericalism and the disorders of the Democratic Six-year period. For Angulo, the desire to preserve the fueros would have even been an impediment to go to war, since military defeat could lead to their loss. When the uprising took place, the slogan was followed: "Let's save Religion even if the Fueros perish!". This exclamation, which became famous, had been pronounced for the first time in Zumárraga years before, in 1865, during a meeting of very influential people from Guipúzcoa; that year, Elizabeth II had recognized the kingdom of Italy, the enemy of Pope Pius IX, and since then the anti-liberal Basques had contemplated the possibility of even going to war against the government, giving the religious question priority over the foral.

The liberal Fidel de Sagarminaga also stated in 1875 that linking the fueros to Carlism was a mistake, since it had been the religious question, and not the fueros, that had produced this movement in the Basque-Navarre region, where Unlike other Spanish regions, there had been no Carlist insurrections between 1839 and 1868, during the entire reign of Isabel II. In his work Two words on Basque Carlism (1875) he stated in this regard:

Today it is enough for us to prove that the Basque Carlism is a phenomenon with local accidents, but whose essence does not lie or live alone in that region; that the Fueros have not been in the least part to produce it, and that in it they cannot find support the sedicious and disturbing, to the point that only in the band of the Basque loyalists is the genuine remedy of those institutions.

In the decades that followed, Carlism stood out both for its Spanishism and for its opposition to centralism, advocating a federal and traditional monarchy for Spain.

Background

The French invasion of 1808 and the absence of the monarch created a power vacuum that was taken advantage of by the liberals to seize power in the Cortes of Cádiz and proclaim the Constitution of 1812. In the Indies this has similar consequences but it is unleashed a Creole uprising in favor of independence. Here it could be classified as the first confrontation between royalists, favorable to the Old Regime, and independentistas, who, influenced by new ideas, fight for the independence of the viceroyalties as liberal republics.

The Spanish War of Independence and the Cortes of Cádiz would give rise to a review of political positions in Spain. The Constitution of 1812 defined the initial position of Spanish liberalism, from which progressive liberalism would derive throughout the XIX century. and democratic. The position of traditionalism curdles in a broad program of political reforms presented to Fernando VII on his return from exile and which was known as the "Manifesto of the Persians". The political heir of this ideology will be Carlism.

The most notable counterrevolutionary thinkers of the early XIX century, totally opposed to the constitutional text of Cádiz, were Pedro de Inguanzo, Rafael de Vélez and Francisco Alvarado, "the rancid Philosopher". ">XVIII such as Fernando de Ceballos, Lorenzo Hervás and Panduro or the aforementioned Francisco Alvarado, framed in a European current of reaction against encyclopedism and the French Revolution.

After Rafael Riego's coup d'état that led to the Liberal Triennium (1820-1823), the anti-liberal and counterrevolutionary movement consolidated against him, and in 1822 the Royalist War broke out, where they clashed for the first time in the peninsula the forces of tradition with liberalism, settling in Catalonia the so-called Regency of Urgell. The French intervention of the One Hundred Thousand Sons of Saint Louis decided the war in favor of the royalists.

During the second absolutist restoration —known by liberals as the «Ominous Decade» (1823-1833) and which constitutes the last period of the reign of Ferdinand VII– the absolutists divided between «reformist» royalists —supporters of «softening » absolutism following the warnings of the Holy Alliance, whose military intervention through the One Hundred Thousand Sons of Saint Louis had put an end to the brief experience of constitutional monarchy in 1823 — and the so-called «apostolic» or «ultras», who defended the restoration of a "pure monarchy" that would require other types of reforms, as established in the Manifesto of the Persians. Due to the king's concessions to the liberals, such as the non-restoration of the Inquisition, they would lead a new uprising in 1827, the War of the Aggrieved. The "apostolics" had in the king's brother, Carlos María Isidro —heir to the throne because Fernando VII after three marriages had not managed to have descendants— his main supporter, and for this reason they began to be called "carlistas".

Birth

After the death of his third wife, María Josefa Amalia of Saxony, Fernando VII announced in September 1829 that he was going to marry again. According to Juan Francisco Fuentes, “it is very possible that the king's haste to resolve the succession problem had to do with his doubts about the role that his brother Don Carlos had been playing in recent times. His continuous health ailments and his premature aging—in 1829 he was only 45 years old—must have persuaded him that time was running out. According to his doctor, Fernando made this unequivocal confession in private: & # 34; It is necessary that I get married as soon as possible & # 34; ».

The one chosen to be his wife was the Neapolitan princess María Cristina of Borbón-Two Sicilies, Fernando's niece and 22 years his junior. They were married on December 10 and a few months later Fernando VII made public, through the Pragmatic Sanction of 1830, the Pragmatic approved in 1789, at the beginning of the reign of his father Carlos IV, which abolished the Auto agreed of 1713, a fundamental law of succession. which had:

... the succession of man in man in the lines of Don Felipe V, always before the man more remote to the next female, passing the law, once extinct the greater branch of males, to each of the minors of the foetus, that, successively, and to the disappearance of the precedents, shall be firstborn, and once extinct the agnated descendant of Philip V, rests the right in the next femaleFernando Polo, Who's the King?

- ↑ By descending from the Infanta Catalina Micaela of Austria

In this way, Fernando VII tried to ensure that, if he finally had descendants, his son or daughter would succeed him. At the beginning of May 1830, a month after the promulgation of the Pragmática, it was announced that Queen María Cristina was pregnant, and on October 10, 1830, a girl, Isabel, was born, for which Carlos María Isidro was left out of the succession to the throne, much to the dismay of his ultra-absolutist supporters.

According to the Carlists, and subsequent related historiography, Fernando VII "illegally" promulgated the Pragmatic Sanction of 1789, which, although it had been approved by the Cortes on September 30, 1789, in the time of Carlos IV, was not had been made effective at that time because the imperative mandate was missing and an issue as serious as the change in the law of succession to the Crown did not appear on the Order of the Day of the Cortes. Following this reasoning, they affirmed that, although Carlos IV had tried to repeal the Salic Law through the aforementioned Cortes agreement, the provision had not been promulgated, so it had not entered into force as it lacked a fundamental element for legal validity. The fact is that the subsequent publication of the "Novísima Recopilación" made it necessary to reconvene courts for this purpose to modify the way of succeeding to the Crown, and therefore made it impossible to "resuscitate" the agreement of courts of Carlos IV. It was Fernando VII who sanctioned said agreement through Pragmática, violating current legislation and promulgated it for the benefit of his daughter, the future Queen Isabel II and to the detriment of her brother Carlos María Isidro who until then was her heir.

The «Carlistas» were not resigned to the fact that the newborn Isabel was the future queen and tried to take advantage of their first opportunity due to the illness of King Ferdinand, which gave rise to the «events of La Granja» of the summer of 1832. On September 16, 1832, the delicate health of King Ferdinand VII, who was convalescing in his La Granja palace (in Segovia), and Queen María Cristina, under pressure and deceived by the "ultra-absolutist" ministers headed by Francisco Tadeo, worsened. Calomarde and by the ambassador of the Kingdom of Naples, who assured her that the army would not support her Regency when the king died (and trying to avoid a civil war, according to her own later testimony), she influenced her husband to revoke the Pragmatics promulgated on March 29, 1830 and that closed the access to the throne to Carlos María Isidro. On the 18th, the king signed the annulment of the Pragmatics of the Salic Law, so that the law that prevented women from reigning was back in force. But Fernando VII unexpectedly recovered his health and on October 1 dismissed Calomarde and the rest of the "Carlist" ministers —supporters of his brother, who had cheated on his wife— and on December 31 annulled the repealing decree that had never been issued. had published (since the king had signed it on the condition that it not be published until after his death), but that the "Carlists" had taken it upon themselves to divulge. In this way Isabel, two years old, was once again the heir to the throne.

However, the Carlists and later related historiography narrated these events completely turning them around, stating that it had been the king's wife, María Cristina de Borbón, who had pressured the king to "violate the law", because she was "Wishing to crown her daughter Queen of Spain." The King's illness influenced the Court, where one and the other, supporters of Isabel and Carlos, tried to get the monarch to enact or not the rule. Whether or not it was true that, very shortly before his death, the king had modified his criteria again at the request of the Council of Ministers, and possibly influenced by his brother, the truth is that the reinstatement of the Salic Law did not occur due to a lack of obligatory sanction and promulgation.

The Carlists, in addition to denouncing the illegitimacy of the entire process, maintained the existence of this last act of the monarch, and in any case the legal nullity of the Pragmática, considering that the king could have been pressured, or else hid the provision never to enter into force. Queen Elizabeth's supporters, for their part, considered that any valid norm after the repeal of the Salic Law did not exist, in their opinion perfectly valid and, therefore, the heiress to the throne was the monarch's daughter, the future Queen Elizabeth. Be that as it may, the Carlists and later related historiography claimed, the king had made the decision without the help of the Cortes.

The new government headed as Secretary of State by the "reformist" absolutist Francisco Cea Bermúdez and from which the "ultras" have been separated, immediately takes a series of measures to promote a rapprochement with the "moderate" liberals, thus initiating a political transition that after the death of the king will continue the Regency of María Cristina de Borbón. It is about the reopening of the universities, closed by Minister Calomarde to avoid the "contagion" of the Revolution of July 1830 in France, and, above all, the promulgation of an amnesty on the same day of its constitution, the 1st of October 1832, which allowed the return to Spain of the majority of the exiled liberals. In addition, on November 5, he created the new Ministry of Public Works, a reformist project boycotted by the "ultra" ministers.

From their separation from power, the "ultra-absolutists", relying on the royalist Volunteers, confronted the new government and the king's own brother refused to swear Isabel as princess of Asturias and heir to the throne —arguing that King Ferdinand VII did not have the power to promulgate the Pragmatic Sanction and that, therefore, the Salic Law was still in force—, for which Ferdinand VII forced him to leave Spain. Thus, on March 16, 1833, Carlos María Isidro and his family left for Portugal. A few months later, on September 29, 1833, King Ferdinand VII died, starting a civil war for the succession to the Crown between "isabelinos" —supporters of Elizabeth II—, also called "cristinos" by his mother, who assumes the Regency, and "Carlistas" —supporters of his uncle Carlos.

Carlist Wars

In the 19th century there were several insurrections by the Carlists against successive liberal governments, known at that time as civil wars. When a new insurrection broke out in 1936, which led to a more destructive war, it became customary to refer to those of the <span style="font-variant:small-caps;text" century as "Carlist wars" -transform:lowercase">XIX, and reserve the term "Civil War" for 1936–1939.

First Carlist War (1833-1840)

It was the most violent and dramatic, with almost 200,000 deaths. The first uprisings in support of Carlos María de Isidro, proclaimed king by his followers under the name of Carlos V, occurred a few days after the death of Ferdinand VII, but they were easily put down everywhere except in the Basque Country (now the Basque Country).), Navarra, Aragon, Catalonia and the Valencian Region.

It was above all a civil war, however it had its impact abroad: the absolutist countries (Austrian Empire, Russian Empire and Prussia) and the Papacy apparently supported the Carlists, while the United Kingdom, France and Portugal supported Isabel II, which resulted in the signing of the Treaty of the Quadruple Alliance in 1834.

Both sides had great generals (Zumalacárregui and Ramón Cabrera on the Carlist side, and Espartero on the Elizabethan side, which resulted in an arduous and prolonged conflict). But Carlist exhaustion led a part of them, the Moderates led by General Rafael Maroto, to split and seek an agreement with the enemy. Negotiations between Maroto and Espartero culminated in the Embrace of Vergara in 1839, which marked the end of the war in the north of the country. However, Cabrera held out at Levante for almost another year.

Second Carlist War (1846–1849)

It wasn't as dramatic as the first and had much less impact. The conflict lasted discontinuously between 1849 and 1860. Its main battlefield was the rural areas of Catalonia, although there were some episodes in Aragon, Navarra and Guipúzcoa. In 1845 the Infante Don Carlos had abdicated in favor of his son Carlos Luis de Borbón, Count of Montemolín, who takes the name of Carlos VI, as a pretender to the crown. Commanded by General Cabrera, the conflict is characterized by guerrilla actions that do not achieve results, causing Cabrera to have to cross the border, although some pockets resisted until 1860 in actions more typical of banditry.

Third Carlist War (1872–1876)

The third Carlist war began with the armed uprising of supporters of Carlos VII against the liberal monarchy of Amadeo I and later against the government of the First Republic and Alfonso XII, son of Isabel II, proclaimed king by the general Martinez Campos in Sagunto.

The main conflict scenarios of this war were the rural areas of the Basque Country, Navarra and Catalonia, with less repercussions in areas such as Aragon, Valencia and Castilla.

This new conflict was one of the factors that destabilized the constitutional monarchy of Amadeo I and the first Republic.

During the time this war lasted, the Carlists controlled some areas of Spain, especially what they called "the North" (which corresponded to the Basque Provinces and Navarre) and some areas of Aragon and Catalonia. For the administration of this territory, official bulletins were issued, coins were coined and a penal code was promulgated, which among other things punished with the death penalty the attempt to destroy the independence or integrity of the Spanish State.

The war ended in 1876 with the conquest of Estella (Don Carlos's court) and the flight to France of the suitor. There were some subsequent attempts at an uprising, taking advantage of the discontent over the loss of overseas possessions in 1898, but they were unsuccessful.

Carlism during the reign of Isabel II

After the Vergara Agreement, Carlism, despite having been reduced to clandestinity, continued to unite a good sector of Spaniards. Vicente Marrero affirms that it was even the majority among the population. Not surprisingly, for some years the newspaper La Esperanza, directed by the Carlist Pedro de la Hoz, would become the newspaper with the largest circulation in the Spanish press of the time.

The first Carlist thinkers, who published their writings in the late 1830s and early 1840s, were Vicente Pou, Magín Ferrer, Pedro de la Hoz, Atilano Melguizo and Félix Lázaro García.

To definitively reconcile the Spaniards, overcome the dynastic dispute and unite all the monarchists, the balmist party defended the marriage between Isabel II and the Count of Montemolín (eldest son of Carlos María Isidro, in whom he would abdicate to facilitate the project). In his newspaper El Pensamiento de la Nación, Jaime Balmes incessantly defended this marriage, and after meeting in Paris with the Count of Montemolín, he published a manifesto that appeared in La Esperanza dated May 23, 1845, written by Balmes himself, in which Carlos Luis was conciliatory, stating:

I know very well that the best way to avoid the repetition of revolutions is not to be determined to destroy as they have lifted up, nor to lift up everything they have destroyed. Justice without violence, reparation without reactions, prudent and equitable transaction among all interests, take advantage of how much good our elders have read to us without countering the spirit of the time in what encloses healthy. Do my policy here.

Balmes's project would fail, on the one hand, due to the hostility of Narváez, María Cristina and King Luis Felipe of France, as well as Isabel's personal preferences, but also due to the intransigent position of the Count of Montemolín, represented by the Carlist newspaper La Esperanza, which opposed the Balmesesian idea that Carlos Luis was simply the king consort and postulated the thesis of a dynastic union like that of the Catholic Monarchs, on equal rights ("so much mounts"). Menéndez Pelayo would write about it:

It certainly failed the company of Balmes for incompatibility of principles, as some imagine, but for incompatibility of people.

In addition, the policy of the new liberal regime revolved around French influence, when the moderates ruled, and the English, when the progressives did. Given the need to marry Elizabeth II, the July Monarchy in France (with which Carlos Luis, loyal to the dethroned Bourbons, did not want to come to terms) he decided on Francisco de Asís de Borbón with the plan that if the marriage had no succession, the Orleans dynasty would ascend to the Spanish throne. On the other hand, since Francisco de Asís was not to have authority over his wife, Spain would be subject to the influence of Luis Felipe. For its part, England supported the candidacy of Enrique de Borbón y Borbón-Dos Sicilias, of progressive ideas, and the Carlists, lacking international allies, were left alone.

After the failure of the marriage with Isabel, a part of the supporters of the Count of Montemolín provoked a new insurrection, with a main focus in Catalonia, known as the Matiners War, which lasted until 1849. Carlist parties rose up again in 1855, after a new failure in accordance with the reigning dynasty, and in 1860 there was an attempt by General Ortega in San Carlos de la Rápita, in which Carlos Luis himself was imprisoned, who was forced to renounce his dynastic rights, resigns of which he later said that it had not been valid.

After Carlos Luis died in 1861, his brother Juan de Borbón y Braganza, who held the rights of the Carlist dynasty, recognized Isabel II as Queen of Spain, but her stepmother, María Teresa de Braganza, Princess of Beira, protested against this act and published in 1864 his famous "Letter to the Spanish", in which he proclaimed Don Juan's son, Carlos de Borbón y Austria-Este, later known by his supporters as Carlos VII, as the legitimate heir of the rights of Carlos Luis. Only Don Juan's wife, mother of Carlos VII, refused to sponsor such an idea, but she finally gave in to the determined intentions of Don Carlos, who began to receive visits from the most important Carlist characters (Marichalar, Algarra, Tristany, Mergeliza, etc.), publishing a manifesto of his in La Esperanza shortly after. In a conference with Vicente de la Hoz, the means of reorganizing the Carlist party were studied.

Meanwhile, faced with revolutionary pressures, Isabel II caused the fall of Narváez in 1865 and the ascent of O'Donell and, although she had resisted it, she ended up recognizing the kingdom of Italy, an enemy of the Church. In the debate that arose in the Cortes for this reason, Aparisi y Guijarro said that said recognition implied the divorce between the throne and the elements of the right, and since the throne was already divorced from the revolutionary liberals, the queen remained without support, Aparisi then pronouncing a phrase from Shakespeare that Benito Pérez Galdós would recall years later in his Episodios nacionales: "Goodbye, woman from York, queen of sad destinies!". Three years later he exploded the revolution that would dethrone it. In the last period of the Elizabethan monarchy, the so-called neo-Catholics or Nocedalistas had already unified their efforts with the Carlists in the so-called "Monarchical-religious Communion" or "Catholic-monarchical Communion".

In 1866 Don Carlos wrote to his father declaring himself head of the Carlists and in 1868 he chaired a Council in London with the main figures of Carlism to relaunch the movement, taking advantage of the crisis of the Elizabethan regime. In said meeting, a political and administrative plan was drawn up, the course of conduct to follow was established, the manifesto that he would address to the Spanish the following year was prepared, and he took the title of Duke of Madrid.

In her subsequent exile in Paris, Elizabeth II would personally meet Charles VII, whom she would come to recognize as the legitimate king of Spain.

Carlistism during the Revolutionary Sexennium

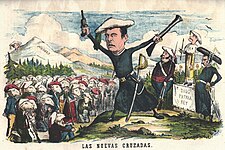

The Revolution of 1868 that dethroned Isabel II and the subsequent Six-Year Revolution brought about a great resurgence of Carlism, which began to participate in parliamentary politics. For its defense of the traditional monarchy and Catholic unity (which would be suppressed by the Constitution of 1869), the so-called neo-Catholics, former Elizabethans, were definitively integrated into the Carlist party, which acquired the name of Catholic-Monarchic Communion. The revitalization of the legitimist cause was shown in the creation of Carlist newspapers in most of the provinces of Spain, among which stood out in Madrid —along with the veteran La Esperanza— La Regeneración, El Pensamiento Español and the satirical El Papelito (which reached a staggering circulation of 40,000 copies), and, in Barcelona, La Convicción and the satirical Lo Mestre Titas, among others. For the first time the Carlists officially concurred in elections, and in the 1869 constituents they obtained some twenty seats.

On June 30, 1869, the suitor published a Letter-Manifesto, known as «Letter from Don Carlos to his brother Don Alfonso», in which he stated that he aspired to reign in Spain and not to be the mere head of a game. This letter, written by Antonio Aparisi y Guijarro, who would become one of the suitor's closest collaborators, was reproduced by the Carlist press, distributing hundreds of thousands of copies on flyers.

Don Carlos wanted to distance himself from the idea of obscurantism and absolutism that many Spaniards associated with Carlism, and stated that he did not intend to return to the past; he wanted to give freedom to the Church and maintain the concordats with the Holy See violated by the revolutionary government, but not undo the confiscations; he proposed to maintain Catholic unity, but not to restore the Inquisition, since every Spaniard should be a king within his house. His objective was to establish a genuinely Spanish government, built, according to Balmes's thinking, on the old foundations, with a fundamental law and representative courts, but without political parties. In the suitor's government program, the municipalities and councils should have broad administrative autonomy; the legitimized property had to be intangible and the work should be regulated with minimum rates of remuneration, retirement laws and insurance. As for freedom of thought and expression, all scientific progress and cultural advantage from abroad should be accepted without restrictions, but the borders should be absolutely closed "to dissolving, anti-social, criminal or heretical propaganda." According to Aparisi and Guijarro, with these ideas of Don Carlos, a constitution could be formed twenty times more liberal and less imperfect than the one that Prim, Serrano and Topete would string together. However, according to Arturo Masriera, despite Don Carlos's sincere, tolerant and attractive language, few found out about that program and the liberals maintained their highly negative image of Carlism.

In August 1869 there was a first attempt at an uprising in favor of Carlos VII, which failed due to poor organization, as a result of which, among others, the former mayor of León Pedro Balanzátegui was shot. In October 1869 Don Carlos handed over the political-military leadership of Carlism to Ramón Cabrera, who resigned in March 1870 due to discrepancies with the pretender and with notable figures of the Carlist movement. Don Carlos then decided to personally assume the leadership of Carlism after a conference that took place on April 18, 1870 in Vevey (Switzerland) in which he brought together notable Carlists, creating a central board of the party that acted legally in Spain, the Catholic-Monarchic Communion, which was presided over by the Marquis of Villadarias and whose secretary was Joaquín María de Múzquiz and local councils in the municipalities where Carlism was established. A network of casinos and Carlist centers was also organized to promote the Carlist ideology, a strategy that proved successful, since in the 1871 elections Carlism won 51 deputies in the Congress of Deputies. During these years, the so-called "porra party" would carry out violent actions against Carlist newspapers and casinos. In August 1870 there was a new Carlist attempt in the Basque Provinces, which quickly failed.

In addition to Aparisi, thinkers such as Antonio Juan de Vildósola, Vicente de la Hoz, Gabino Tejado, Francisco Navarro Villoslada and Bienvenido Comín also advised Don Carlos during the Revolutionary Sexennium.

The appointment of Amadeo of Savoy in 1871 as King of Spain greatly upset Catholics, who called him "the son of the Pope's jailer" and considered him to come from a usurping house affiliated with Carbonarism and Freemasonry. Months later the third Carlist war broke out, which would last until 1876. During the war, the First Republic, the Serrano dictatorship, and finally, after the pronouncement of Martínez Campos, the monarchical restoration of Alfonso XII, which reduced support for the Carlists, would take place in Spain.

Carlism during the Restoration

Although the military defeat of 1876 caused Carlism to lose a good part of its potential, it did not mean its disappearance. In March 1876 Don Carlos published a manifesto in Pau maintaining his combative attitude, for which he had to leave France, went to England and made several trips to America, Europe, Africa and Asia. Finally, he settled in Venice, in the Loredan palace, which was given to him by his mother in 1881. Meanwhile, he reorganized his party, and once again entrusted its leadership to Cándido Nocedal as his delegate at the end of the war.

In 1879 Cándido Nocedal, as the pretender's representative in Spain, reorganized Carlism emphasizing its character as a Catholic movement and relying on a network of related newspapers that carried out a very aggressive policy, which confronted him with Carlist sectors in favor of the Union Católica, a group led by Alejandro Pidal, who ended up joining the conservatives of Antonio Cánovas del Castillo.

King Alfonso XII tried to attract the Carlist and conservative masses, stating that he would be "Catholic like my ancestors and liberal like my century." This tendency was embodied in the pidalismo, formed by former moderate elements of Carlism who did not want to join the liberal-conservative party, and who supported Catholic unity in the religious order. This movement had the newspaper La Unión as its official organ and was led by brothers Luis and Alejandro Pidal, who founded the magazine La España Católica.

From the newspaper El Siglo Futuro, founded by Cándido and Ramón Nocedal, the Carlists campaigned against the Constitution of 1876, affirming that the Catholic-liberals (mestizos, as they were called) were a monstrous aberration, since liberalism was irreconcilable with Catholicism and constituted "the synthesis of all errors and heresies", for which reason Catholics should only be active in the diametrically opposed party, that is, in the Carlism. With this character of a Catholic organization in the fight against all liberal errors, they were based on the Syllabus of Pope Pius IX, obtaining the support of the vast majority of the clergy and many Catholics.

The son of Pedro de la Hoz, Vicente de la Hoz y Liniers, and his brother-in-law Antonio Juan de Vildósola, founded the newspaper La Fé, a continuation of La Esperanza. In 1881 La Fe welcomed the possibility of collaborating with the Catholic-liberals in the Catholic Union, for which reason it confronted El Siglo Futuro, which opposed the same. One of the objectives of the Catholic Union was for Cándido Nocedal, as the leader of a Catholic party, to accept the new organization and submit to it and its Junta. Nocedal's refusal unleashed serious controversies, which took on a personal nature, among the newspapers El Siglo Futuro, La Fé, El Fénix and The Union. La Fé went so far as to say that Nocedal represented “the neo-Catholicism ingested in the old Carlist party to dominate and distort it”. At the beginning of 1884 Alejandro Pidal was appointed Minister of Public Works in a government headed by Cánovas, which consolidated the position of Nocedal and the intransigent Carlists, who said that this fact implied acceptance by Pidal of political liberalism.

In 1885 Cándido Nocedal died and it was expected that his son Ramón would be named his successor, but Don Carlos preferred to assume the leadership of the party himself. On the occasion of the birth of Alfonso XIII in 1886, Don Carlos published a manifesto to the Spanish claiming the rights to the Crown. Shortly after, he made a second trip to South America and gave a new organization to his party, dividing Spain into four large circumscriptions and naming a leader for each one, who were León Martínez Fortún, Juan María Maestre, Francisco Cavero and the Marquis de Valdespina. The organization thus took on a certain military aspect, since all the bosses were. At this time, the first Carlist Youth in Spain was organized in Madrid, chaired by Reynaldo Brea, and soon after many others were created.

From El Siglo Futuro, Ramón Nocedal, dissatisfied with his secondary role, did not stop attacking La Fé, which represented the bellicose tendency of the Carlist party. Don Carlos asked for peace among his supporters, but he was not heard. In 1888 the suitor indicated to Luis María de Llauder the publication of his famous writing, The Thought of the Duke of Madrid . Nocedal opposed it, saying from El Siglo Futuro that in the traditionalist communion the first thing was God, then the Homeland and lastly the King, in accordance with the order of the famous Carlist motto, implying that Don Carlos commanded or supported things contrary to God and the Fatherland.

Outraged, Don Carlos expelled Nocedal from the party, who even said that Don Carlos had liberalized. Félix Sardá y Salvany fought point by point El Pensamiento and at the end of July 1888 El Siglo Futuro published a manifesto, reproduced by many provincial newspapers, presenting the program of the new fundamentalist party, which supported "the entire Catholic truth". In the so-called Burgos Manifesto, the fundamentalists defended, among other things, the reestablishment of the Inquisition.

Don Carlos, in order to have a faithful press organ, founded in Madrid, through Llauder, El Correo Español, and at the beginning of 1890 he appointed his delegate for all of Spain the Marquis of Cerralbo, which improved the organization of the party, naming heads and regional and provincial boards, and founding numerous circles and youth. His delegation coincided with the beginning of the Catholic congresses and the birth of militant political Catholicism, without anti-dynasty of any kind, so the position of the Carlists in this regard was rather one of abstention. Not wanting to abdicate their legitimacy, they maintained that the total triumph of the Church could only be obtained with that of Don Carlos, and to the doctrine of the "lesser evil" they opposed that of the "greater good", refusing any type of compromise.

Until then Carlism was the only organized regionalist party in Spain, without attacking its national unity in accordance with the words of Don Carlos: «political centralization, administrative decentralization». The administrative decentralization supposed the recognition of the privileges of the different Spanish regions in the social, civil, financial and administrative orders. In Catalonia, the Catalanist Union was founded in 1891, unaffiliated with Carlism and indifferent to religious principle, which drew up the Bases de Manresa. This implied an autonomy that went beyond that defended by the Carlists, by virtue of which Catalonia had to become a State within the Spanish State. The Carlists stayed away from this trend, which was in conflict with their Spanish program. However, they led the campaign in favor of the Basque-Navarrese fueros.

From 1890 the Marquis of Cerralbo was at the forefront of Carlism, rebuilding it as a modern mass party, centered on local assemblies, called Círculos, which numbered in the hundreds throughout Spain and with more than 30,000 members in 1896 These assemblies were copied by other political forces; In addition to political activity, they carried out social actions, which led Carlism to an active participation in opposition to the political system of the Restoration. The Carlist party would get five deputies in 1891, seven in 1893, ten in 1896, six in 1898, two in 1899, participating in coalitions such as Catalan Solidarity in 1907, together with regionalists, fundamentalists and republicans.

Starting in 1893, Juan Vázquez de Mella, director of El Correo Español, became the parliamentary leader and main ideologue of Carlism, having a wide influence on Spanish traditionalist thought. Mella was the main person in charge of drafting the so-called "Act of Loredán" in 1897, which was a programmatic update of traditionalism.

When the Spanish-American war broke out in 1898, Don Carlos ordered from Brussels all the Carlists not to do anything that could compromise the success of the war and to help with all their might those in charge of defending Spanish integrity in Cuba and the Philippines; and he went so far as to formally threaten a new civil war if they did not fight to defend the national honor, saying that he could not assume responsibility for the loss of Cuba before the History. Many believed that the loss of the colonies would cause a revolution in Spain that would bring about the overthrow of the dynasty, similar to what happened in France due to the loss of Alsace and Lorraine in 1870. For this reason, after signing the Treaty of Paris, considered as a national dishonor, the opinion that the Carlists would launch into a new civil war, taking advantage of the discontent of the Army and the people, was widespread.

The uprising was prepared and some generals and military units had deals with the Carlists, but the government found out about the conspiracy, General Weyler withdrew from it and the European powers showed their opposition to the movement, so it failed. The Marquis of Cerralbo left Spain and presented his resignation, being replaced in December 1899 by Matías Barrio y Mier. The Carlist youths attributed the failure to the opposition of Doña Berta, Don Carlos's second wife, who was said to have arrested Don Carlos when he had already left for Spain. However, some Carlists thought that this was the best opportunity. to succeed, and they tried to carry out the uprising without the authorization of the main Carlist leaders. Salvador Soliva hatched a conspiracy in Barcelona, which failed due to the lack of secrecy and organization with which it was carried out, and in October 1900 the Badalona uprising took place, in which 60 men unsuccessfully attacked the Civil Guard barracks.. Games also appeared to Igualada, Berga and Piera, and outside Catalonia in Jijona and Jaén, which were quickly undone. This attempt brought Carlism to a crisis and caused the government to suspend all Carlist newspapers in the country for a few months and close all its circles.

Matías Barrio y Mier, professor at the Central University and deputy for Cervera de Pisuerga, preferred political tact and achieved the reconciliation of the Marquis de Cerralbo and Juan Vázquez de Mella with Don Carlos, which materialized in the candidacy of Vázquez de Nick for Barcelona.

In the 1901 elections, Carlism won six deputies, seven in 1903, four in 1905 and fourteen in 1907 thanks to their participation in Catalan Solidarity. From then on, the Carlist aplecs began, which mobilized large masses, and many new Carlist press titles that propagated the doctrine of the party.

The anti-clerical policy of the government, materialized in the persecution of the religious Orders, gave a greater increase to Carlism, which allied itself with fundamentalism —disappearing the confrontation between both traditionalist formations— and even with the Silvelistas, to combat the projects of the government defended by Canalejas, who had proposed to imitate Waldeck-Rousseau, telling the liberal newspapers that "there is no true liberalism without anti-clericalism." At the same time, Catalanism increased and a secessionist Basque nationalism appeared, with which the Carlists fell out from the beginning.

In Catalonia, Lerrouxist republicanism presented itself, with the unofficial support of the governments, as the fence against Catalanism; but in opposition to it, the Catalan Solidarity was established in 1906, which had its origin in the so-called Law of Jurisdictions, repressive against crimes against the Homeland and the Army, which placed it under military jurisdiction.

Among the Catalan Carlists there was a wide divergence of opinion on whether they should ally with the Catalanists. One part considered that this union was contrary to the principles, history and character of the Carlist party, especially taking into account the anti-religious tendency of some of the parties that were to integrate the coalition. However, El Correo Catalán and some Carlist politicians, such as Pedro Llosas, managed to get the Carlists free to join the movement or not according to the agreement reached by the Carlist regional chief of Catalonia, José Erasmo de Janer, after consulting with Don Carlos, who had initially been against this coalition.

The electoral success of Solidarity brought nine deputies to Congress for the Carlists, which produced great enthusiasm among the traditionalist masses, who came to believe that Solidarity would put an end to the regime and facilitate the triumph of Don Carlos. However, in the rest of Spain the opinion of the Carlists was always against the entry and permanence of Carlism in Solidarity.

On July 17, 1909 Don Carlos died in Varese and was buried in Trieste. His death coincided with the Tragic Week in Barcelona, which led to the disappearance of Solidarity. On this occasion, the Carlists sided with the government of Maura, who was opposed to the triumph of anti-clerical projects.

Haimism

On July 18, 1909, the pretender Charles VII died and was succeeded as legitimist pretender by his son, Jaime de Borbón y Borbón-Parma, known among his supporters as Jaime I and in Catalonia and Valencia as Jaime III. The Carlists came to be called "jaimistas" or simply "traditionalists" or "legitimists". Barrio y Mier had also died the same year and Bartolomé Feliu was appointed chief delegate, whom Don Jaime kept in office.

Don Jaime found his party well organized in all the regions and provinces, with meetings in almost all the districts and with numerous circles, youths and requetés throughout Spain, as well as many newspapers, weeklies, magazines and even two newspapers (acquired popular subscription machinery): El Correo Español and El Correo Catalán.

The 1910 elections brought eight deputies to Congress and four Jaimist senators to the Senate. The jaimista representatives dedicated themselves mainly to combating the project of the Padlock Law, and the policy against religious orders by the Canalejas government. The traditionalists also organized demonstrations and rallies throughout Spain, reaching the permanent session in Congress, and dedicated themselves to fighting against republicanism, an ally of the government in the anti-clerical campaign. Confrontations between Republicans and Carlists were common, especially in Catalonia, where the confrontation between Requetés and Lerrouxistas in San Feliú de Llobregat on May 28, 1911 stood out, which resulted in one Carlist death and four Lerrouxistas, in addition to seventeen wounded. At that time, Requeté began to organize itself as a youth organization of the party, under the direction of Joaquín Llorens and Fernández de Córdoba.

At the beginning of 1913 Bartolomé Feliu was replaced as chief delegate by the Marquis of Cerralbo, constituting, under his presidency, a traditionalist National Board, made up of the regional chiefs and the representatives in the Cortes. In a meeting held in Madrid on January 30 and 31 of the same year, ten commissions were appointed (Propaganda, Organization, Circles and Youth, Requetés, Treasury of Tradition, Press, Elections, Social Action, Defense of the Clergy, and Legal Defense. of the legitimists prosecuted for political crimes) and rules were issued for the reorganization of the party throughout Spain. This allowed the founding of new traditionalist circles and an increase in propaganda.

However, the fact that Don Jaime did not marry caused uneasiness among his followers, who began to fear that if their leader did not have a successor, the party would be headless and the rights of the Spanish crown would go to the ruling branch, so the question of legitimacy of origin would end.

Salvador Minguijón, in a series of articles and conferences, began to maintain that the union of the Jaimistas with the independent Catholics and with Maura was necessary to implement a minimal program, without overthrowing the reigning dynasty, and try to change the liberal regime slowly, by way of evolution. El Correo Catalán and other newspapers supported this strategy, but many jaimistas protested against it, since it disregarded Don Jaime's rights and they understood that the minimal program and the alliance with the Catholic-liberals implied a surrender and the abandonment of the military character of the party, seeing in what was called minguijonismo a new nocedalismo, but with a more pronounced dynastic and liberal inclination, which brought it closer to the pidalism.

In 1914 Don Jaime declared in an interview from Paris that «he did not conceive of new parties and that although his could be reinforced with new elements, it could never lose its character; that he had inherited duties and the duties were not waivable ». However, El Correo Catalán continued to support Minguijón's tendencies, and at a Youth Congress held in Barcelona a subject was even presented consisting of Don Jaime having to renounce his rights, come to Spain and become the head of a new party in accordance with the indicated tendencies.

In Catalonia, the alliance with Catalanism caused an internal confrontation within the party. According to Espasa, many traditionalists from the rest of Spain and a part of the Catalans were opposed to it. The director of El Correo Catalán, Miguel Junyent, maintained a close alliance with the Regionalist League, in such a way that in the elections the newspaper followed the line set by the Lliga on regionalist matters. The Catalan jaimists opposed to this trend were led by Dalmacio Iglesias. In 1915 they sent a message to Don Jaime, which was adhered to by some traditionalist circles in Barcelona (not the central one) and in Catalonia, where they called for the political independence of the party. To defend the trend of so-called "pure legitimism", Iglesias founded the newspaper El Legitimista Catalán. the one who declared rebels to all those who held meetings not authorized by the regional chief.

The new orientation given to the elections by the national board was not complied with by the regional board of Catalonia, which led to the appointment of another, which distanced the Lliga party. In June 1916, Juan Vázquez de Mella gave a speech in Congress in which he specified the difference between the autonomy of the League (regionalist nationalism) and the autarchy (national regionalism) that the Jaimists supported. As party theoretician, Mella's approaches were incorporated into the traditionalist program. However, El Correo Catalán opposed the new direction, and trying to reach harmony, a political action committee was appointed that established as a rule "neither always with the Lliga, nor always against the Lliga". », but always with accidental alliances and based on a «confessional, Catholic and Spanish regionalism». The Assembly of Catalan Parliamentarians of 1917 and the revolutionary general strike with which it coincided in Barcelona in July, ended up distancing a good part of the Jaimistas from the Lliga, but not El Correo Catalán.

In the Basque provinces and Navarra, nationalist agitations also broke out, for which reason the Marquis of Cerralbo, in a letter addressed to the Marquis of Valdespina, the legitimist provincial chief of Guipúzcoa, gave the orientation that, as a regionalist party, the party Jaimista was a regionalist, but defended the unity of Spain and was "incompatible with liberal regionalisms".

In 1918 Dalmacio Iglesias fought the draft Catalan Statute drawn up by the autonomists that established a State for Catalonia, citing its liberal and non-denominational nature. The campaign against the Statute was authorized by the authorities and the party press, with the exception of El Correo Catalán and some other newspaper. In November of the same year, the collective Pastoral of the Bishops of Catalonia declared that "Jesus Christ has absolute right over the peoples in the political order" and condemned the neutral tendencies with respect to religion.

In addition to these internal struggles within Jaimism, there was another that ended up dividing the party. On the occasion of the First World War, the jaimistas, led by Vázquez de Mella, sided with the Central Powers, arguing that England and France had been the promoters of liberalism and the adversaries of Spanish power. Thus, they carried out an active campaign to maintain Spain's neutrality in the war against those who wanted the country to join the allies, threatening civil war if the government intervened in the European conflict.

However, during the Great War Don Jaime lived under house arrest in the Austro-Hungarian Empire for his support of France and the allies, with almost no communication with the Jaimista political leadership in Spain, which Vázquez de Mella continued to lead, with a character germanophile. At the end of the war, Don Jaime had a manifesto drawn up from Paris, dated January 30, 1919, in which he stated that his orders had not been obeyed and that against their will the masses had been dragged in favor of the Central Powers, so the complete reorganization of the party was necessary. With this manifesto he publicly disapproved of the conduct followed by Mella, Cerralbo and the entire leadership of the party.

When the National Board learned of the manifesto, it agreed on February 5 that it should suspend its publication until a committee of the Board met with Don Jaime, but this commission could not obtain the visa for the passports and Don Jaime ordered for the manifest to be published. All the editors of El Correo Español who sympathized with Mella were expelled and the suitor added that in terms of the principles and conduct of those who recognized him as chief, he "was the only competent judge", affirmation that the mellistas saw as a model of Caesarian absolutism, contrary to their model of traditional monarchy. Given these facts, the board unanimously agreed that they could not accept the conduct and principles of Don Jaime, so they decided to continue the game without the suitor. Mella would still publish an article attacking Don Jaime in El Debate.

For his part, Miguel Junyent and elements of El Correo Catalán were in favor of Don Jaime and opposed to the mellistas and facilitated the final division of the party. In 1919 the Aragonese Pascual Comín y Moya was appointed representative of Don Jaime with the title of Secretary. Although Comín's prestige prevented the party from completely falling apart and strong nuclei remained faithful, he held office for a short time. Don Jaime needed someone younger for the arduous work of reorganization, so in 1919 Luis Hernando de Larramendi, a lawyer, writer and orator who had stood out in the Traditionalist Youth of Madrid, was appointed secretary general. Hernando de Larramendi began to reorganize the movement with great difficulties, since there were clashes among those loyal to Don Jaime.

To reorganize the party, the jaimistas held a great meeting in Biarritz on November 30, 1919, chaired by Don Jaime, where Dr. José Roca y Ponsa had an outstanding intervention. In Biarritz Larramendi was able to present the reconstituted structure of the Traditionalist Communion and its activity allowed it to bring together dispersed elements, although the party no longer had the strength of previous years. Jaimista parliamentary minorities were reduced to a few deputies and senators. At the end of the leadership of Hernando de Larramendi in 1922, the movement had diminished in size, but it had youth full of enthusiasm, particularly in the regions where the mellista split had wreaked less havoc: Catalonia and Navarre.

Vázquez de Mella and his supporters founded the newspaper El Pensamiento Español in Madrid, a continuation of the previous editorial line of El Correo Español, and created the Traditionalist Catholic Party, who also wanted to gather the fundamentalists and the social-catholic. El Correo Español, which remained in the hands of the jaimistas, lost a good part of its subscribers and disappeared two years later, in 1921.

The jaimistas, under the direct leadership of the pretender, who showed great interest in the social question, would defend "socialist" positions, in the manner of Charles Péguy or English distributism, inspired by the social doctrine of Church, and emphasized the foralista character of the party.

In the 1919 elections, the Catalan Jaimistas Bartolomé Trías and Narciso Batlle and Joaquín Baleztena from Navarre were elected as deputies, as well as two Mellististas, Luis García Guijarro and José María de Juaristi, and a fundamentalist, Manuel Senante. Two jaimistas, three mellistas and two fundamentalists were elected as senators.

For their part, the Catalan mellistas held an assembly in Badalona in May 1920 in which they appointed a regional board and the provincial ones, but new dissidences soon began. The delay in holding the national assembly and in publishing the program motivated some elements to try to hold it themselves. Some traditionalists who met in Zaragoza without Mella, did not do anything practical nor did they have sufficient authority to draw up a norm, nor sufficient elements to achieve their objectives. Many mellista traditionalists, seeing that the opportunity to form a great party had been lost, abandoned politics, and little by little total disorganization took place. A good part of the old Jaimista circles and newspapers disappeared and the death of Vázquez de Mella put an end to Mellismo.

In 1920 Carlism still suffered the separation of an important sector, led by Minguijón, Severino Aznar and Inocencio Jiménez, who founded with Ángel Ossorio and Gallardo the Social Popular Party, of Christian democrat ideas; and another around the Diario de Valencia, a former fervent defender of Jaimism, led by Manuel Simó and Luis Lucia, which soon lost its traditionalist character and recognized first the Alfonsine monarchy and then the Second Republic. group would found the Valencian Regional Right.

Coinciding with this time of fragmentation of Carlism, the first Free Trade Unions were formed in the Traditionalist Central Circle of Barcelona, which confronted the anarchists of the National Labor Confederation using the so-called Talión Law and they did some murder. Its founders were Jaimista workers, although later not all members of the Union were linked to Carlism.

In the December 1920 elections, three Jaimista deputies were elected to Congress, among them Batlle, and the fundamentalist Manuel Senante, as well as five traditionalist senators, including Jaimista Trías and Mellista Ampuero.

In 1922 Hernando de Larramendi resigned from his position and was succeeded by the Valencian José Selva Mergelina, Marquis of Villores. The Spanish situation worried Don Jaime so much that he called prominent Jaimistas to Paris with whom he held talks. Likewise, the Jaimista youth met in Zaragoza to reach important agreements.The Marquis de Villores, Don Jaime's new secretary, centralized the direction of the Communion from Valencia, where he lived. Thanks to his work, he managed to revive the movement in the Valencian Region, but the Primo de Rivera dictatorship, together with the pre-revolutionary period that led to the proclamation of the Second Republic in 1931, gave him new difficulties. However, the great activity of the Marquis de Villores made it possible to reorganize the party in Guipúzcoa, Vizcaya and La Rioja.

Don Jaime was informed of the preparation of the 1923 coup through Colonel Arlegui, who was involved with General Martínez Anido. When the coup took place, the jaimistas of the Requeté and the Free Unions collaborated with the military in Barcelona. Some jaimistas believed that there was a possibility that Alfonso XIII would leave Spain, as Manuel García Prieto advised him, and that Don Jaime would enter the country and be recognized as king with the coup. Although Primo de Rivera was from Alfonsino, General Sanjurjo and Arlegui were supporters of Don Jaime.

However, the Military Directorate that was formed treated the traditionalists like any other party and although Don Jaime initially gave a vote of confidence to the regime, the majority of the Jaimistas stayed away from it. In 1925 Don Jaime published a manifesto critical of the Dictatorship, which began to prohibit the acts and close the circles of the jaimistas, who began to oppose the regime and saw their forces greatly diminished.

For their part, the mellistas joined the Patriotic Union, considering that with the recognition of the freedom and protection of the Church, and the restoration of the principles of order and authority, a good part of the program had been recognized traditionalist.

Carlism during the Second Republic

Carlismo arrived very weakened at the beginning of the republican period. With the proclamation of the Second Spanish Republic, Don Jaime published a manifesto in which he conditioned his support for the regime on the evolution it took, stating that if the Republic took a revolutionary but not a moderate course, it would fight to the death "against the anti-human communism at the head of all patriots. Later the Carlists would adopt a definite position against the Republic.

The proclamation of the Republic would facilitate the appearance of new Jaimist newspapers in different regions of Spain. In 1931 the weekly Reacción was founded in Barcelona; in Pamplona, La Esperanza; in San Sebastián, The Basque Tradition; in Bilbao, The Rifle; and in Lérida, El Correo de Lérida; to which were added the Jaimista newspapers that had already been published: the prestigious daily El Correo Catalán of Barcelona, El Pensamiento Navarro of Pamplona, and the weekly El Cruzado Spanish from Madrid, The Traditionalist from Valencia, La Verdad from Granada, La Tradición from Tortosa, La Comarca de Vich, Joventut from Valls and Seny from Manresa, among others. Those responsible for El Cruzado Español, heir to the disappeared El Correo Español, took steps to convert it once again into an official newspaper and organ of the party, a consideration that the old fundamentalist newspaper El Siglo Futuro would finally end up assuming. During the republican period, more newspapers related to the Traditionalist Communion would appear.

The situation in Spain allowed the rapprochement of jaimistas, mellistas and fundamentalists, who began to act jointly. However, in the constituent elections of 1931 they still appeared without having formalized their reunification. The jaimistas obtained four deputies, the Count of Rodezno, Joaquín Beunza, Julio de Urquijo and Marcelino Oreja, in a Basque-Navarre coalition with the PNV, from which the fundamentalist Manuel Senante was excluded by the nationalists for not being Basque by birth. The fundamentalists obtained three deputies, José María Lamamié de Clairac, Ricardo Gómez Rojí and Francisco Estévanez Rodríguez, in coalition with the agrarians. Once both formations were united, the deputy elected by Álava José Luis Oriol would later join this traditionalist minority.

Don Jaime died in Paris on October 2, 1931, as a result of a fall from a horse. He was succeeded at the head of Carlism by his uncle, Alfonso Carlos de Borbón y Austria-Este, brother of Carlos VII . Despite being 82 years old, he agreed to lead the party, stating that he was doing it to fulfill his duty.

Don Jaime had held talks with Alfonso XIII for the reunification of his branches of the house of Bourbon, with the proposal to establish Jaime as head of the house of Bourbon in exchange for him naming the infante Don Juan, son of Alfonso XIII. The negotiations ended abruptly with the death of Don Jaime, who had signed the Fontainebleau pact with Alfonso XIII, but Don Alfonso Carlos decided not to confirm it until he was sure that the pact saved traditionalist principles. In the end, no definitive agreement was reached with the Alfonsine dynasty.

The fundamentalists returned to Carlism at the end of 1931. In January of the following year, Don Alfonso Carlos reorganized the Traditionalist Communion with a Supreme Board under the presidency of the Marquis de Villores, which included the Count of Rodezno, Juan María Roma and Joaquín Beunza (former Jaimistas); Manuel Senante and José María Lamamié de Clairac (former integrists) and José Luis Oriol (former Maurista). In May 1932, the Marquis de Villores died and was replaced by the Count of Rodezno as president of the Central Board. During this period, Carlism, as a counterrevolutionary movement completely opposed to the Republic, again acquired great strength throughout Spain, much higher than it had been in previous years.

The atmosphere of tension and radicalization that existed from the end of the Dictablanda and the beginning of the Second Republic is confirmed in the continuous street confrontations. On January 17, 1931, a traditionalist meeting was held in Bilbao that ended in a collision between Socialists and Republicans, resulting in three Socialist deaths. In Pamplona there was also a confrontation in 1932 between the Carlists and the Socialists in which two Socialists died and in August of the same year there was a fight in Letux (Zaragoza) in which some Republicans were killed, including the mayor of the town. In 1933 there were also incidents in Madrid, Zaragoza and Fuencarral, where a young traditionalist, María Luisa Leoz, was injured.

The Marqués de Villores died in 1932, when the traditionalist propaganda campaigns had spread the vitality of the Communion throughout all the regions of Spain. The anticlericalism of the Azañista biennium would encourage many Catholics opposed to secularism and Marxism to join traditionalism. In this way, Carlism entered a phase of expansion, increasing the activity and number of circles or creating women's sections (the "Margaritas"). The Traditionalist Communion had significant support in the Basque Country, Navarra, Catalonia and also in Andalusia, where the lawyer Manuel Fal Conde, who came from fundamentalism, quickly stood out.

On August 10, 1932, General Sanjurjo attempted a coup in Seville and Madrid. Although Carlism was not officially committed, many traditionalists participated in it and its youth had serious confrontations with the leftist parties. In Madrid, three Carlists died in the shootout: the student José María Triana and the military Justo San Miguel y Castillo. As a consequence of the events of August, the government took important measures against right-wing parties, suspending Carlist newspapers and imprisoning a large number of traditionalist affiliates. Furthermore, despite the initial timid support of some Carlists for the Statute of Catalonia, the party ended up opposing him. The Carlists of Álava and Navarra also opposed the Vasco-Navarro Statute, breaking their relations with the PNV.

For the general elections of 1933, the traditionalists reached an agreement with the Spanish Renovation monarchist party, led by Antonio Goicoechea, and established an electoral center in order to run together in the elections: Traditionalists and Spanish Renovation (TYRE). Twenty-one traditionalist candidates from fifteen different provinces were elected as deputies, integrated into the lists of the right-wing coalition: the Count of Rodezno, Esteban Bilbao, Luis Arellano and Javier Martínez de Morentín, from Navarra; José Luis Oriol, for Álava; Marcelino Oreja, for Vizcaya; Francisco Estévanez, for Burgos; Miguel Martínez de Pinillos and Juan José Palomino, for Cádiz; Miguel de Miranda, for Logroño; Romualdo de Toledo, for Madrid; José Luis Zamanillo, for Santander; the worker Ginés Martínez Rubio and Domingo Tejera, for Seville; Lamamié de Clairac, by Salamanca; Jesús Comín and Javier Ramírez Sinués, for Zaragoza; the Baron de Cárcer, for Valencia; Joaquín Bau, for Tarragona; Casimiro de Sangenís, for Lérida; and Gonzalo Merás (traditionalist and Popular Action militant at the same time), for Oviedo. All of them constituted the traditionalist minority in Congress. The radical-CEDA alliance and the Marxist threat pushed the Traditionalist Communion to a position of extreme right, causing the radicalization of its bases.