Camelidae

The camelids (Camelidae) are a family of artiodactyl mammals of the suborder Tylopods made up of three current genera and eight extinct genera. The genus Camelus—Bactrian camel, wild camel, and dromedary camel—inhabits the arid Asian and African plains; and the genera Vicugna —vicuña and alpaca— and Lama —guanaco and llama— in South America from the Andean heights to Tierra del Fuego and the Chaco.

Features

Camelids are strictly herbivorous, with long, slender necks and long legs. They differ from ruminants in that their dentition shows traces of vestigial central incisors in the maxilla, and the presence of true canine teeth, separated from the premolars by a space called a diastema, in both the maxilla and mandible. The musculature differs. from other ungulates since the legs attach to the body only at the upper thigh, rather than being connected from the knee up by skin and muscle.[citation needed]

Another difference with this ancient clade of placental mammals is that their stomachs have three chambers instead of four; its upper lip is divided into two parts, each one movable separately. As a distinctive and unique feature in other mammals, they have elliptical red blood cells.[citation needed]

In addition, camels, dromedaries, alpacas and llamas have induced ovulation, that is, the female generates a gamete, during or just before mating due to an external stimulus, contrary to regular cyclical ovulation.[ citation required]

Camelids don't have hooves; instead they have two nailed toes on each foot and plantar pads, the only typopods (Greek for "padded feet") extant among artiodactyl mammals. Most of your weight falls on these tough, fibrous pads. Andean camelids have the ability to use them to gain more grip on rocky terrain.

All camelids walk in a particular way due to their locomotion system; On the march, the two limbs on the same side move simultaneously, unlike horses, for example, which have an interspersed canter.

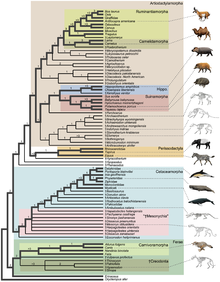

Taxonomy

The current systematics includes all the current representatives in the Camelinae subfamily, which is subdivided into tribes:

History and evolution of camelids

Evolutionary history

South American camelids are related to camels found in Africa and Asia. The fundamental morphological difference is that they have a hump and are larger.

Modern camels are the result of a long and complex evolutionary process that originated in North America in the Late Eocene about 40 million years ago. At that time, small mammals called Protylopus petersoni appeared, similar to small guanacos only 80 centimeters tall. From this group, different species originated that, in their evolution over millions of years, adapted to different environmental conditions and gradually increased in size.

Fossil finds show that about 20 million years ago, camelids dominated the flatlands of North America. A detailed study of these remains allowed them to be classified into four groups with their own characteristics (Titanotylopus, Paracamelus, Megatylopus and Hemiauchenia).

Of these four groups of camelids, only Paracamelus and Hemiauchenia gave rise to all the current species.

The tylopods had 4 toes on their feet, but sometime during the Oligocene and Miocene they lost the lateral toes, the earliest types of camelids probably had no hump and resembled llamas. During the Oligocene some camelids developed long necks that allowed them to see over trees and shrubs.

Due to the cooling of the earth during the Miocene and Pliocene, the savannahs increased and the camelids underwent selective processes that gave rise to adaptations to the new conditions, such as the elongation of their legs, the appearance of crowns on their teeth, necessary to chew the grasses. Many camelids became extinct due to these events, such as Oxydactylus (a camel with a neck like a giraffe), Stenomylus (resembling a very small gazelle) or Alticamelus (It was more than 5 meters tall, and was the first of the giant camelids).

From the Pliocene and the Pleistocene the temperature began to be more varied throughout the globe and North America and South America joined, with the closure of the Isthmus of Panama, as well as North America with Eurasia through the closure of the Strait from Bering.

A consequence of these changes was the arrival of new predators in North America and, on the other hand, the fact that the camelids that had emigrated found themselves with native predators of those places, to which they were poorly adapted, and whose better defense mechanism was the flight to desert environments (Africa and the mountainous areas of South America).

The Paracamelus that lived during the Miocene had some giant species such as the genera Gigantocamelus and Alticamelus that could exceed four meters in length. height (larger than current elephants). Some Paracamelus migrated approximately 3 million years ago (beginning of the Pleistocene) through the Bering Strait, from North America to Eurasia, and spread throughout Europe, North Africa and China. The fossil record in Spain shows that paracamelids roamed in herds very similar to those of adult camels.

The only fossil of the species Paracamelus aguirrei was found in Spain. This species arrived in the Iberian Peninsula from North America or North Africa. The arrival of this species during the Late Miocene coincides with the event of greatest dispersal and entry of taxa to the Iberian Peninsula, known as the upper Turolian. Fossils of paracamelus have also been found in nearby areas (Alicante, Murcia) dated at 6.1 million years, contradicting the date estimated for the arrival of camelids in Europe 3 million years ago.

It is from the Paracamelids that the humpbacked camels evolved: the camel and the current dromedary, which belong to the genus Camelus.

On the other hand, the Hemiauchenians originated from the pliauchenia that appeared between 9 and 11 million years ago in the North American prairies. Giving origin to the genus hemiauchenia 10 million years ago. Some species of this genus migrated south, about 3 million years ago, during the transition from the Pliocene to the Pleistocene, (almost at the same time that the ancestors of the camelini tribe migrated to Asia for the Bering Strait), passing through the Central American isthmus, invading the plains and pampas of South America.

Although a study published in 2007 by Jiao tong university in Shanghai based on mitochondrial phylogenetics suggests that the divergence of the two tribes may occur in the early Miocene, it is much earlier than is deduced from the fossil record (11 million years). Furthermore, by reconstructing the evolutionary history of camelids on the basis of cytb (molecular clock of mitochondrial genomes) sequences, he suggested that the division of the Bactrian camel and the dromedary may have occurred in North America before the Camelini tribe migrated from North America. to Asia.

Already in South America the separation between the genera llama and vicuña occurred approximately two million years ago.

About 10 to 12 thousand years ago, in the Pleistocene ice age, all camelids in North America became extinct. In South America, the Hemiauchenia and the Paleolama disappear, leaving only the guanacos of the genus Lama and the vicuña of the genus Vicugna.

Natural history of South American camelids.

Human contact.

Fiedel has estimated that the entry of humans into the Americas corresponds to about 10,000 years ago. However, his dating presents inconsistencies with fossil records found in South America with earlier dates. The time required for the complete population of the continent seems to indicate that the closest date would be about 30,000 years ago. The entrance of the human being to South America can be dated, then, about 15,000 years ago.

The constant increase of coastal nomadic societies, probably caused the entry into the interior of the continent, producing the implementation of agricultural techniques that allowed the supply of the increasingly numerous human population; Thus, the domestication of plants and animals allowed the hierarchical sedentary lifestyle of tribal civilizations, which with the passing of time would gain complexity and dominate the entire continent.

The entrance to the interior positioned these towns in mountainous complexes that offered a climatic diversity that would promote agriculture. The punas and the steppes were fertile lands that promoted the planting of potatoes and corn and, collaterally, the domestication of the Andean Camelidae, to cover the needs of clothing, meat and animal fat.

The Vicugna vicugna and the Lama guanicoe constituted a very precious element in the conformation of the nascent civilization. Their fine wool was very warm and their meat and milk supplemented the protein intake of the agricultural diet.

Product of this domestication, the species were genetically modified over time by human selection. Like corn, which is not a natural fruit, the Andean camelids were altered according to the needs of the new predator.

The current Lama glama and Vicugna pacos are the result of this evolutionary process; They present abundant wool and a considerable increase in size, which does not correspond to the non-human natural requirements of the geographical region.

The economic base of the Tahuantinsuyo Empire.

Of all the civilizations that dominated the Andes, the Tahuantinsuyo would be born in the heart of Peru, in Cuzco, and would finally end up reaching an extension from the Colombian Pastures to the Chilean Pampas. Its political-economic configuration was very complex and was based on the domination of small groups that gradually subdued in their expansionism. Control of the Andes gave them total control of the various climates that formed the basis of vertical agriculture.

This complex system presented ideological and material demands that extended from the ritual realm to the utilitarian aspect of economic transportation. Said needs were covered by the camelids that in a short time became the elemental base of the empire.

Spanish and American chroniclers such as Garcilaso de la Vega and Huamán Poma de Ayala recorded in their writings the operation of the empire and its relationship with the Andean camelids that were used according to their physiological characteristics, such as resistance or fineness of the wool according to a complex hierarchical state.

Murra mentions that the wool was woven to dress the people and as a ritual offering; an individual's social position was evidenced by the quality of the fabric he used. The Alpaca, which had the thickest wool and was difficult to weave, was characteristic of the poorest sector of the population, which also ate potatoes and could only taste corn and dress with llama wool on ritual occasions. The highest level of society, the leaders and officials reserved the right to use vicuña wool, which, in addition to presenting the finest fur, was scarce; the so-called Acllas were women selected to exclusively weave this wool that, in addition to clothing the elite, was offered in different religious festivities, various vicuña leather garments were burned in the center of the square as an offering to Inti, the supreme god.

The llamas, for their part, were reserved mainly for the transport of trade, although it was not very effective, since they died on the roads and several of these extra animals had to be taken, it was the most resistant camelid. In the times of Inti Raimy, it is mentioned in the chronicles that both the harvest and the new seeds were sprinkled with llama blood as a ritual act of gratitude to the Pachamama.

Finally, the guanaco, due to its wild characteristics, played a marginal role and did not represent an important class in the development of the empire. He was occasionally hunted, but this was unusual.

Camelidae in the Spanish Empire.

Flames were inefficient means; Despite the complex systems of roads, this prevented them from supporting the weight of Silver, Gold and Mercury, so they were replaced by mules and donkeys [citation required]. As for personal transport, the horse would be implemented mainly.

The implementation of trade reforms to increase Spain's dominance in America, reduced its textile production capacity, the Iberian Peninsula was the only one that could market dresses inside the New World from the port of Cádiz. This made Vicuña wool stop being used to dress the elites, now the fine cloths were made of linen [citation required]

The Spanish brought flocks of sheep to the South American continent, so the ponchos that were woven were made of this wool, which in addition to being easier to handle, was more profitable and economical.

The proliferation of herds of sheep and goats came to the detriment of the Andean camelids [citation needed] The Camelidae then lost their leading role in society and despite the fact that their survival is not directly threatened, until today they were reduced to a clearly marginal environment [citation required].

The current Camelidae.

Currently, South American camelids are considered to be of less concern in terms of extinction risks, however it is recognized that they are subject to preservation, especially the wild species of the Guanaco and the Vicuña, which continue to be hunted in some areas of the Andean complex.

The alpaca and the llama have spread to a more diversified popular sphere, their presence in the various central squares of the capitals and even as an advertising figure demonstrate this; In areas of Peru and Chile, the llama continues to be used occasionally for transportation and as a source of food, while alpaca wool continues to be a raw material for textile production, even when it is a minority sector.

The alpaca, llama, guanaco, and vicuña are the result of early Protylopus petersoni, as are today's Eurasian camelids. Camelidae is a family with a fascinating history that has managed to conquer the world and that even today continues to be closely related to ourselves.

Contenido relacionado

Merostachys

Lophatherum

Gaudinia