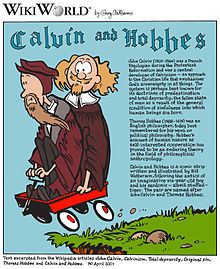

Calvin and hobbes

Calvin and Hobbes is a comic strip written and drawn by Bill Watterson that recounts, humorously, the adventures of Calvin, an imaginative 6-year-old boy, and Hobbes, his energetic and sarcastic stuffed tiger, somewhat pompous, who Calvin believes to be real.

The couple are named after John Calvin, a 16th-century French Reform theologian, and Thomas Hobbes, a 17th-century English philosopher. The comic strip ran daily from November 18, 1985 to December 31, 1995, appearing in more than 2,400 newspapers and with more than 30 million copies sold of its 18 compiled books, which makes it a reference in popular culture even today.

Underneath its apparent simplicity lies one of the most complex comic strips of the late 20th century. Although it draws in part from the fantasies of Little Nemo in Slumberland, by Winsor McCay, its multiple references (Don Quixote, Hamlet, Kafka, Nietzsche, Picasso) and the reflections of the author (in the mouth of Calvin) on art, culture, politics, philosophy, transcendental themes (life, death, God) have turned Calvin and Hobbes in one of the reference comic strips, which has given rise to many and varied interpretations to try to encompass the magnitude of its author's legacy.

The story is loosely set in a typical suburb of today's American Midwest, a location likely inspired by Waterson's birthplace in Chagrin Falls, Ohio. Calvin and Hobbes appear in the vast majority of strips, while the presence of the rest of Calvin's family is much smaller. The most recurring themes of the strip are Calvin's fantasies (in which he escapes from the real world), his friendship with Hobbes, his pranks, his views on political and cultural issues, and his interactions with his parents, schoolmates, teachers and other members of society. A very recurring motif is the dual nature of Hobbes, since Calvin sees him as a living being while the rest of the characters see him as a stuffed toy. However, the strip does not mention any specific political figures (as, for example, Garry Trudeau does in Doonesbury, which touches on issues such as environmentalism or opinion polls). Calvin's strips begin by announcing "the results of the survey of six-year-olds" to his father, as if his position in the family were an elected position.

Due to Watterson's deeply held anti-commercial convictions, and his refusal to be a celebrity, there is hardly any legitimate Calvin merchandise (towels, mugs, etc.) other than the drawings themselves. The few official items are coveted by collectors. Two notable exceptions were the publication of two 16-month wall calendars and the textbook Teaching with Calvin and Hobbes. However, the great popularity of the strip has led to the appearance of many unauthorized products (T-shirts, key rings, etc.) with the motifs of Calvin and Hobbes, often including obscene language far removed from what the original characters represent.

History

Calvin and Hobbes were born when Watterson, whose job as a publicist he detested, began spending his free time pursuing what was his great passion: drawing. He developed several ideas for comic strips, which he submitted to various publishers, but they were all rejected. However, he received a positive response from one of them, advising him to focus on a minor character (the main character's little brother) and his stuffed tiger. Watterson followed this advice, but the new strip based on this character it was rejected by the very publisher that had encouraged him to do it, the United Features Syndicate. Watterson did not give up and, after several more refusals, he finally got Universal Press Syndicate to agree to publish him.

The first strip appeared on November 18, 1985, and it soon became a hit. Within a year it was published in some 250 newspapers, and in April 1987, just 16 months after its inception, it earned an article in the Los Angeles Times. Calvin and Hobbes gave its author two Reuben Awards from the National Cartoonists Society (National Cartoonists Association) in the category of Best Cartoonist of the Year (Outstanding Cartoonist of the Year), the first in 1986 and the second in 1988, being nominated again in 1992. He was also awarded the Humor Comic Strip Award in 1988.

Watterson would take two long breaks in which he did not draw new strips, the first from May 1991 to February 1992, and the second from April to December 1994. In 1995 Watterson sent a letter to the publisher and to all newspapers that published their strips. The letter was published on November 9:

Dear editor, I will stop drawing Calvin and Hobbes at the end of the year. This has not been an impulsive or easy decision to make, and I do it with some sadness. However, my personal interests have changed, and I think I have done what I have been able to within the limits of the delivery dates and the size of the vineyards. I am anxious to work at a more meditative pace, with few artistic commitments. I have not yet decided for future projects, but my link with the Universal Press Syndicate will continue.The fact that so many newspapers have published Calvin and Hobbes is something that will always honor me, and I am very grateful for their support and indulgence over the past decade. Drawing this comic strip has been a privilege and a pleasure, and I appreciate the opportunity. "Surely,

Bill Watterson."

Strip number 3160 would be the last of Calvin and Hobbes, appearing on Sunday, December 31, 1995. It shows Calvin and Hobbes with their sleigh, walking across a completely full of snow and enjoying the scenery, they sit on the sled and Calvin says: "It's a magical world, Hobbes, old friend..." The last scene shows them both going down the snow on the sled while Calvin shouts: " Let's explore it!"

The relationship between Watterson and the publisher

From the beginning, Watterson had problems with the publisher, which prompted him to develop the marketing of the characters and touring the country to promote the first compilation books of the strips, to which Watterson refused. For the author, the integrity of the strip and of the artist was undermined by commercialization, which he saw as the most negative influence in the world of comics.

Watterson became even more frustrated with the gradual disappearance of space for comics in newspapers. He lamented that there was little room for text and essential layout, which were transforming the comic into a watered-down, bland, and unoriginal art form. Watterson strove to make full-page versions of some of his strips (as opposed to the few boxes available from most of them), dreaming of the artistic freedom of classic strips like Little Nemo and Krazy Kat, and giving a sample of the result on the opening pages from The Calvin and Hobbes Lazy Sunday Book.

During Watterson's first layoff, the publisher continued to charge newspapers the same price for reruns of old comic strips featuring the characters. Many publishers disagreed, but had no choice but to agree, fearing sales would drop if they excluded Calvin, given the character's high popularity.[citation needed]

After his break, Universal Press announced that Watterson had decided that he would only sell his Sunday strip if it was allowed to take up half a page of the newspaper, with no possibility of dividing it. This decision was criticized by many publishers and some cartoonists, such as Bil Keane (The Family Circus), who saw Watterson as an arrogant author and reluctant to follow the established norms of the comics industry; criticism that Watterson ignored.

Watterson reached an agreement with the publisher and gained more creative freedom for the Sunday strips. Before the agreement, he had a certain number of cartoons, with little freedom in terms of arrangement (the width of the cartoons varied according to the newspaper in which they were published); after the deal he could use whatever graphic layout he wanted, often very unorthodox. His frustration with the standard layout before the deal is evident in some old strips; for example, a strip published in 1988 was framed in a large panel, but the action and dialogue were placed at the bottom, so any editor could crop the top if he needed to fit the strip into a smaller space. This is how Watterson explains the change:

I took a break after solving a long and tiring struggle to prevent the marketing of Calvin and Hobbes. Looking for a way to rekindle my enthusiasm for new contractual terms, I proposed a new design for Sunday strips that would allow me greater flexibility. To my surprise, Universal offered me the possibility of drawing indivisible half-page strips (much more than I would have been allowed to claim), despite the expected rejection of the editors. The editorial assured me that some editors were delighted with the new format, which appreciated the difference, and were happy with strips of that size; but it is fair to say that that was not the most frequent reaction. They prevented me from the most predictable cancellations of the Sunday strip, but after a few weeks of confrontations with angry editors, the editorial suggested that the newspapers could reduce the strip to the size of the tabloids, which had the smallest leaves.... I stayed with the positive side: I would have complete creative freedom and virtually no cancellations. The outraged editors have convinced me that the biggest Sunday strip aesthetically improved the strips of the newspapers, and made them more fun for readers. The comic strips are a visual medium. A strip with a lot of drawing can be exciting and bring some variety. I'm proud to have been able to draw a big strip, but I don't think that can happen again in the near future. In the press business space costs money, and I suspect that most editors believe that the difference does not offset costs. Unfortunately it is the fish that bites the tail: since there is no space for graphic improvements, the strips are only simple drawings and, if they are simple drawings, why do they need more space?.

Calvin and Hobbes remained wildly popular despite the changes, and Watterson was able to continue to hone his style and technique in the Sunday strips without fear of losing buyers.

Promotional items

Bill Watterson is famous for his insistence that comic strips should remain solely an art form, and his reluctance to use Calvin and Hobbes in any kind of marketing venture, despite that it would have generated millions of dollars in additional income. This is how he explained it in a press release in 2005:

Actually, when I started drawing the strip, it wasn't against marketing. But then I reflected and realized that every product could violate the spirit of the strip, contradict his message and take some of the work I loved. If the publisher had demanded it, making the decision would have taken me thirty seconds of my life.

Watterson even entertained the idea of creating an animated version of Calvin and Hobbes, and expressed admiration for the art form. In an interview in The Comics Journal, in 1989, he stated:

If we look at old movies from Tex Avery and Chuck Jones, we can see things that a simple drawing on paper can't show. The animators can play with distortion and exaggeration because the animator can control what you see and how long you see it. The movements hardly have time to show up and the spectator is not aware of the incredible rampage he has witnessed. In a comic strip you can only show the key moments of the action, but not the before and after, unless you want the strip to give the feeling of watching a photogram movie by frame, so you would surely lose the effect you were trying to get. In a comic strip you can suggest a sense of movement or time, but in a much simpler way than a cheerleader can get. I have great respect for good animation.

Because of these concerns, she was asked if she wasn't a little scared to think of what voice Calvin would have. Watterson responded that he was "very scared." Although he was interested in the visual possibilities of animation, he was uncomfortable with the idea of selecting the voices for his characters. He also wasn't attracted to the idea of working with an animation team to develop a job that he had always done alone. Ultimately there was never any animated Calvin and Hobbes series. Watterson wrote, in the Calvin and Hobbes Tenth Anniversary Book, that he was proud that his strip was an "entirely personal" and that every drawing and every line of dialogue was his work.

Excluding the compilation albums, two 16-month calendars (1988-1989 and 1989-1990), the book Aprendiendo con Calvin y Hobbes (Teaching with Calvin and Hobbes) and a T-shirt for a comic book exhibition, all merchandise featuring the characters (like rear window stickers showing Calvin urinating on a company logo) are unauthorized. As Watterson noted in the comments on one of his compilations, the original image was of Calvin filling a balloon with water from a faucet. After several threats of lawsuits for copyright infringement, the creators of the stickers replaced Calvin with another boy. Watterson, not without some irony, commented, "I misjudged how popular it would be to see Calvin urinating on the Ford logo." Some rare legitimate items were made, given away to sell the strip to newspapers, but never made available. the sale.

Style and influences

The Calvin and Hobbes strips are characterized by sparse but careful drawing, intelligent humor, sharp observations, witty political and social commentary, and well-defined characters. Precedents for Calvin's fantasy world can be found in Winsor McCay's Little Nemo; in Crockett Johnson's Barnaby; in Peanuts, by Charles M. Schulz; in Bloom County, from Berkeley Breathed; in Percy Crosby's Skippy; in Krazy Kat, by George Herriman, or in Mafalda, by Quino, while Watterson's sociopolitical use of the strip refers more to Pogo, by Walt Kelly. Schulz and Kelly, in particular, influenced his ideas and different perspectives on comics in his formative years.

Precedents of troublesome children that inspired Calvin can be found, for example, in Hank Ketcham's Dennis the Menace comic strip, and rebelliousness and the eternal intergenerational conflict appears in Quino's Mafalda (although this is a more politicized and committed strip). A precedent for a relationship between a child and a stuffed toy can be seen in Winnie the Pooh, a character created by A. A. Milne, where the creativity and imagination of the child (Christopher Robin) is accentuated by contact with Winnie the bear and the rest of the stuffed animals (beyond the obvious physical resemblance between Tigger and Hobbes).

The most characteristic features of Watterson's style are: varied and exaggerated expressions of his characters (especially Calvin), the elaborate and strange backgrounds of the child's imagined fantasies, a great sense of movement and frequent visual games and metaphors. In the later years of the strip, with more space at his disposal, Watterson experimented with varying panel sizes and shapes, non-dialogue stories, and greater use of white space. He also toyed with the idea of leaving certain episodes to the reader's imagination, such as the & # 34; Incident of the noodles & # 34; or the contents of the book Hamster Huey and the Gooey Kablooie (Hamster Huey and the Gooey Kablooie ) that Calvin wanted his father to read to him every night. According to Watterson, readers would have been much more imaginative and morbid than he was when it came to describing these episodes.

Watterson's technique was to start the drawing with minimal sketches (although the longer Sunday strips required more elaborate work); he later used to use a sable brush and India ink to finish the drawing. He was very careful with his use of color, pondering for a long time the exact colors he would use in the Sunday strip.

Art and academia

Watterson used the strips to criticize the art world, especially the unconventional snowmen created by Calvin. When Miss Woodworm (Miss Wormwood, Calvin's teacher) reproaches him for wasting class time drawing incomprehensible things (for example, a Stegosaurus mounted on a spaceship), Calvin exclaims "my failing confirms me at the cutting edge.". His first explorations of snow as a means of expression began when one of his snowmen melted due to the heat. His next sculpture “is about transcendence. As it melts, it invites the viewer to contemplate the evanescence of life! This work speaks to the horror of our own mortality", paraphrasing Ecclesiastes. Over the years, Calvin's creative instincts diversified, including drawing on sidewalks, or as Calvin defines them, examples of suburban postmodernism.

Watterson is also directly critical of academia. Calvin writes a revisionist biography, enlisting Hobbes to take pictures of him showing typical six-year-old activities, such as playing sports, to show a childhood adjusted to normality. In another strip, he is very careful in writing his " artistic manifesto", since "an artist's manifesto always says more than his own art" (Hobbes: "you have written Weltanschauung wrong").

In general, Watterson's satirical essays are aimed at both sides. He attacks both commercial artists and those who are supposed to be outside of that circle. On a walk in the woods, shortly after Calvin started his stegosaurs in spaceships, he says to Hobbes:

The hard way for us, post-modern avant-garde artists is to decide whether we are commercial. Do we allow our work to be promoted and exploited by a market that only wants newness? Do we participate in a system that turns good art into bad art so that the masses can consume it better? Of course, when an artist becomes commercial, he renounces his status as a marginalized and a freethinker. It accepts the empty and transcended values that art should transcend. He sells the integrity of his art in exchange for fame and wealth.

What the hell, of course I will.

HobbesIt hasn't been that hard."

Watterson discusses the classic distinction between "high" and "low" in various strips and releases in them concepts such as power, hegemony, subjectivities, appropriations and symbolic violence, among many others. He also analyzes the concepts of the cultural industry and mass society, as well as the controversies that arise from the notions of alienation and manipulation, always loaded with an ironic tone.

Visual distortions

On many occasions, Watterson creates strips with strange visual distortions: inverted colors, neo-cubist objects, and so on. Only Calvin is able to perceive these alterations, which seem to illustrate his own changing point of view.

In the Calvin and Hobbes tenth anniversary compilation (Tenth Anniversary Book) Watterson explains that some of these strips were metaphors for his own experiences, showing, for example, his conflicts with the publisher. In 1989 a Sunday strip (usually in color) was fully drawn using inverted colors. Calvin is accused by his father that "your problem is that you see everything in terms of black and white", to which the boy retorts: "sometimes it is!", a retort used by Watterson himself.

Temporary references

When the strips first appeared, Calvin's life and games were those of someone living in the northern hemisphere. Calvin could be seen making snowmen or riding his sleigh in the winter, or having water balloon fights in the summer. Calvin goes to school, has vacations, and celebrates Christmas or Halloween.

Though Watterson shows temporal references such as school years, summer vacation, various field trips (where allusions to previous excursions are made), and characters are aware of the passing of the years (such as "Vote Dad 88" or " we've entered the 1990s") the characters don't age and Calvin never celebrates a birthday (the only birthday listed is that of Susie Derkins, a friend of Calvin's). But Watterson just follows an unwritten rule of almost every comic strip, like the forever children in Peanuts or the characters in Krazy Kat (even though they celebrate every New Year).

Although Calvin does not age, there are references in two strips (November 18 and 19, 1995) to Calvin as two and three years old, and his feeling that "a lifetime's experience has made me bitter and cynical." "This is a photograph of me from when I was two years old," he tells Hobbes as they leaf through a family photo album, concluding: "Isn't it strange that our past seems so unreal to us? It's like looking at someone else's photo.” Although Calvin's age is suspended at six years, he is shown in a past tense even though he never stops being that age. Since suspension of disbelief is so prevalent in comics, readers accommodate the suspension of disbelief, accepting that Calvin "was literally never a six-year-old."

Ironically, in an early strip, Calvin's father criticizes him for not living in the moment: "Yeah, I know. You think you'll have six years all your life."

Social criticism

Watterson also used the strip to speak about American culture and society, admitting that the content of the strips could be seen as a sort of self-portrait. With few exceptions, there are no references to characters or current events, so his comments necessarily tend to generalize. He expresses his frustration with public apathy and decadence, with commercialism and with the media. Calvin is often seen "absorbed" on television, while his father speaks with the author's voice trying to instill his values in Calvin.

The most frequent form that Watterson uses for his criticisms is the comments, from a more cynical perspective, that Hobbes makes about Calvin's unhealthy ways. Although more than a direct intervention, it boils down to sly comments or letting Calvin figure it out for himself. In one strip Calvin tells Hobbes about a science fiction story he has read, where machines have turned humans into zombie slaves. Hobbes comments on the irony of the machines controlling us instead of us, when Calvin exclaims, "What time is it? My favorite show is about to start!" and he runs off to watch television, leaving Hobbes to contemplate the irony of the situation.

Watterson also expresses his frustration with the human condition in a more philosophical way. Calvin admires Hobbes for not being human, something the tiger often repeats. Calvin's affection for Hobbes accentuates his misanthropy. Some of the most touching strips are those in which they both show their mutual affection for him. "Not so loud", Calvin sobs as he hugs his friend, "...you're going to make me cry." Calvin frequently makes fun of his father's routine and monotonous life., and often discusses with Hobbes his desire to behave like an animal to "get the most out of life."

In short, given the timeless themes that Watterson employs in his strips, his social critique can be imported into the present.

Main characters

Calvin

First Appearance: November 18, 1985

Named for the 16th-century theologian John Calvin (founder of Calvinism and a deep believer in predestination), Calvin is an impulsive, creative, imaginative, energetic, curious, and selfish six-year-old boy who is never told his true love. last name. Despite his age, he enjoys a large vocabulary that rivals adults, and an amazing capacity for philosophy. All this implies that he comes from a cultured family, as reflected in this anecdote:

- Calvin: «Dad, do you live in me in the hope that my future achievements can redeem your mediocre existence and that, in some way, will compensate for all the opportunities you have lost in life?»

- Father of Calvin: «If so, I will have to rethink my strategy. »

- Calvin (later to his mother): «Mom, Dad has insulted me again. »

His clothing usually consists of a red and black striped shirt, black pants, and brown shoes. Compulsive comic book reader, he adores pop culture, which includes modern clothing or technology and his great passion is dinosaurs. However, his most vulgar experiences become the most valuable, contrasting with the models of behavior and morals that his parents try to instill in him. He chews gum regularly, despite Hobbes' criticism, and is a subscriber to Chewing magazine. This is how Watterson describes it:

Many people think Calvin is inspired by a child of mine, or based on detailed memories of my own childhood. I don't really have children, and I was a fairly quiet and obedient child, almost the opposite of Calvin. One of the reasons that makes it fun to write Calvin's character is that I often disagree with him. Calvin is autobiographical in the sense that he thinks about the same issues as me, but in this, Calvin reflects more my maturity than my childhood. Many of Calvin's conflicts are metaphors of myself. I suspect that many of us grow old without growing up, and that within each adult (sometimes very in) there is a child who wants everything to be done in their own way. I use Calvin as a way out of my immaturity, as a way of keeping my curiosity about nature, as a way of ridiculing my own obsessions, and as a way of commenting on human nature. I wouldn't want to have Calvin in my house, but on paper, it helps me draw and understand my life better.

Calvin has a deep dislike for school, which he tries to avoid on numerous occasions ("...I'm smart, I don't need 11 more years of school!..."). Another of the issues that most concern him is Christmas. Watterson uses these strips to criticize Christmas materialism and consumerism. Calvin is forced during these parties to be "nice" if he wants to receive all the gifts he has asked for. He is especially obsessed with the figure of Santa Claus: «to what extent is he impartial or fair? does he really see all the kids all the time? do you take extenuating circumstances into account?"

Calvin, when he appears solo, often breaks the fourth wall.

Hobbes

First Appearance: November 18, 1985

In the classic "fellows" tradition, Hobbes represents Calvins potential maturity and outer consciousness. To all the characters in the strip, Hobbes is nothing more than a stuffed toy, but Calvin sees him as an anthropomorphic animal, twice his height, with ideas and behaviors of his own. But when the perspective turns to another character, readers only see a stuffed animal, usually sitting in a bent position. Watterson explains this bizarre dichotomy: "When Hobbes is a stuffed toy in one panel, and alive in the next, I juxtapose the real point of view with Calvin's, and invite the reader to decide which is the real one."

However, whether Hobbes is an inanimate object is questioned in several strips: when Hobbes jumps on Calvin (leaving the boy dirty and disheveled). The incident in which Hobbes ties Calvin to a chair and the subsequent anger of his father who asks how he could have tied himself up. In a very early strip, Calvin claims that Hobbes ate a classmate who annoyed him (and Hobbes certifies it). There are no more strips that show Hobbes doing something to another person, which would be nothing more than a punctual humorous resource. This is how Watterson described Hobbes:

Hobbes received the name of a 17th century philosopher (Thomas Hobbes) who had a negative view of human nature. Hobbes is inspired by one of our cats, a gray one that we called Sprite. Sprite not only provided me with Hobbes' long body and facial features, it was also the model of his personality. He was bonachón, intelligent, friendly and enthusiastic. Sprite suggested to me the idea of Hobbes jumping over Calvin when he got home. In most animal stories, humor comes from their humanized behavior. Of course, Hobbes walks upright and speaks, but I try to keep his feline side, both in his physical porte and in his attitude. Your reservation and touch seem to me very gatunos, with its hardly content pride of not being human.

Like Calvin, I often prefer the animal company to people, and Hobbes is my ideal friend idea. The so-called "truck" of my strip—the two versions of Hobbes—usually misunderstood. I don't think of Hobbes as a doll that collects life miraculously when Calvin appears. Nor do I think of Hobbes as a product of Calvin's imagination. The nature of Hobbes' reality doesn't interest me. Calvin sees Hobbes in one way, and everyone else sees him from another. I show two versions of reality, and each one makes sense to the participant who sees it. I think that's how life works. We don't all see the world the same way, and that's what I draw in the strip. Hobbes treats more about the subjective nature of reality than about life-saving dolls.

Thomas Hobbes' most famous work was Leviathan, whose description of the human condition refers to Calvin's psychology and behavior as "...unpleasant, base and brutal". Hobbes, the tiger, is much more rational and aware of the consequences than Calvin, but rarely intervenes in the child's problematic behavior, beyond oblique warnings (after all, the consequences of his behavior will suffer Calvin and not him). He has a habit of stalking and attacking Calvin, especially when the boy comes home from school. Hobbes is often sarcastic to comment on Calvin's hypocrisy about things he doesn't like.

Although early strips show Calvin snaring Hobbes in a snare (with a tuna sandwich as bait), a later strip (August 1, 1989) implies that Hobbes is, in fact, "older" that Calvin and that he has spent his whole life with the child. Watterson subsequently did not consider it important to establish how Calvin and his tiger met.

Side characters

Calvin's Parents

Father's first appearance: November 18, 1985

First apparition of mother: November 27, 1985

At first, Calvin's parents were criticized by readers for being unhearted and unnecessarily sarcastic. (Calvin's father has pointed out that what he really wanted was a dog.) I think it was rare for a strip to focus on the exasperating aspects of children without leaving much room for sentimentality. Usually we only see Calvin's parents when they react to him, therefore as secondary characters. I have tried to make them more real, with a reasonable sense of humor about what it means to have a child like Calvin. I think they do better than I would.

Calvin's mother and father are your typical middle-class American couple. Like other characters, his practical sense of life and moral canons are used to contrast with Calvin's view of life. Calvin's father is a lawyer, specifically a patent attorney (Watterson thought that specificity would be funnier); his mother is a housewife. The names of the parents are never released. Calvin calls them "Dad" and Mama", and among themselves they use expressions like "darling" or "honey". According to Watterson the name was not important, only the fact that they were the "dad" and the "mom" Calvin's. This situation brought him problems in the strips in which Calvin's father's brother, Uncle Max, stayed home for a week and couldn't call either of them by their names. Max never appeared again.

Susie Derkins

First Appearance: December 5, 1985

Susie Derkins, the only major character with a first and last name, is Calvin's neighbor and classmate. Named after the Watterson wife's family dog, she made her first appearance as a new student in Calvin's class. In contrast to Calvin, Susie is serious, businesslike, and intelligent. Her demeanor is calm and civil, and she complies with the stereotypes of a girl, such as playing house or having tea with her stuffed animals, even though the way she plays takes on high levels of cynicism.

Even though the two disagree, they have a lot in common. Occasionally Susie appears with a stuffed rabbit, Mr. Rabbit (Mister Bun) at the same time that Calvin appears with Hobbes. But Calvin doesn't see the stuffed rabbit as an animated being, as it's his point of view, and it's not shown as Susie sees it. Although in an imagined fantasy of Calvin's (while he and Susie are playing house) the rabbit is represented as a boy (Calvin and Susie's son). This is how Watterson explains the relationship between the two:

The first strips with Susie focused on the love/odium relationship, and it took me some time to sterilize their relationship with Calvin. I suspect that Calvin is attracted to her and expresses it trying to screw her up, but Susie is discouraged and puzzled by Calvin's rarities. This encourages Calvin to be even more rare, and a good dynamic is established. None of them understand very well what happens, something that is probably true in most relationships. Sometimes I imagine a strip from Susie's point of view would be interesting, and after so many strips on children, I think it would be a great idea to throw a strip on a girl, drawn by a woman.

Miss Woodworm

First Appearance: November 21, 1985

Miss Wormwood is Calvin and Susie's teacher. Like the rest of the characters, she acts as Calvin's counterpoint. In the first strips she appeared drawn in a very disproportionate way, with a small head on a voluminous body, but over the years she adopted a more proportionate anatomy. She always dresses in polka-dot dresses, and is often seen exhausted from facing Calvin over and over again. The most recurring scenes in which Miss Woodworm appears (always within the class) consist of arguments and replicas with Calvin, apart from frequent punishments (sending him to the principal's office). Her thinking is reflected in an ironic comment: "Not only do we have to instill discipline in them, we also have to be psychologists." Watterson himself takes pity on her:

As some readers guessed, the name of the Sta. Carcoma comes from the devil's apprentice in Letters from the devil to his nephew de Clive Staples Lewis. I feel a great sympathy for the Sta. Carcoma. We see signs that you're wanting to retire, that you smoke too much and take many medicines. I think you really believe in the value of education, so you don't have to say you're a unhappy person.

Rosalyn

First Appearance: May 28, 1986

Rosalyn is a teenage student, Calvin's official babysitter when his parents need a quiet night out. She was also once his swimming teacher, she is the only babysitter able to put up with Calvin's antics since...

... probably the only person Calvin fears is his nanny. I put it on one of the first Sunday pages, not thinking of it as a regular character, but the way I intimidated Calvin surprised me, so it has come back a few times. It seems that he also manages to intimidate Calvin's parents, using his desperation to leave home to ask for advances and increases.

Rosalyn and Calvin don't hit it off. They play dirty against each other and most nights end with Calvin grounded and Rosalyn asking for more advances, if the parents want "him back again." There is, however, a strip in which Calvin and Rosalyn play together (at Calvinball ) in exchange for the boy doing his homework afterwards. When the parents return and Rosalyn tells them it's been a quiet night, the father exclaims, "It's too late for jokes, Rosalyn."

Rosalyn has a boyfriend, Charlie, who never appears in the strip but who the babysitter calls from time to time.

Moe

First Appearance: February 6, 1986

Moe represents the typical school bully, and is, in Calvin's words, "a six-year-old boy who already shaved", always shaking Calvin or taking his lunch money. He addresses Calvin as & # 34; tadpole & # 34;, & # 34; puny & # 34; or "dwarf" (Twinky in the original). In the author's words:

Moe is the representation of all the energies I've ever known. It's big, stupid, ugly and cruel. I remember the school was full of idiots like Moe.

Other characters

Other characters that appear occasionally are the school principal (who Calvin often visits when he is grounded), the family doctor, or the aliens Galaxoid and Nebular (to whom Calvin sold Earth in exchange for a collection of leaves from his planet, scientifically classified, which were homework for school).

Calvin's alter ego

Calvin imagines himself as many things, from dinosaur to elephant to explorer to superhero. Three of his alter egos are well defined and will be very recurring:

- Great ManStupendous Man): Calvin recreates himself as a disguised superhero, whose secret identity is Calvin himself. It's actually just a mask and a cape made by his mother. Great Man often "falls defeated" by the powers of the wicked Lady-Mom (your mother) or Girl-Canguro (Rosalyn). However, for Calvin they are moral victories.

E. Great!S. of pride!

Description of the acronym of Great Man.

T. of Tiger, for his ferocity!

U.S. Unique!

PP! Unbelievable Power!

E. Excellent psyche!

N. I'll remember!

Or... How do you spell? What letter do I need?

- The intrepid Captain SpiffSpaceman Spiff): Spiff is a heroic interplanetary explorer. Walk the galaxy and track distant planets (her home, college, neighborhood) fighting all kinds of aliens (his parents, his teacher, Susie).

- Tracking BulletTracer Bullet): Private detective, Hard Boiled style, is less frequent than the previous two. He says he has a couple of friends: "one always goes in my gunpowder, the other comes in bottle".

At least once each of these characters has been used by Calvin to solve a problem. On a test, a polite Calvin asks to go out for a drink of water. When he is outside he transforms into Stupendous Man. He waits for the teacher to come looking for him and pompously enters the class, does Calvin's homework with his superpowers and pompously leaves again without running into the teacher. of the; Calvin failed the exam. On another occasion he needs to solve the sum 5 + 6. As Captain Spiff he blows up planets 5 and 6. Since planet 6 is bigger it is the only one left. Calvin concludes that 5+6=6. Tracker Bullet begins a gloomy monologue when he becomes involved in a dangerous gang of numbers (a school problem), when Derkins is silenced (Susie doesn't want to tell him the answer) and receives a beating from a hired thug (Miss Woodworm won't let him get up from his chair) he discovers who is behind the whole scheme, it is Mister Million. Solution to the problem: 1,000,000 (Susie gets 15).

Hobbes almost never appears in strips starring Calvin's alter egos.

Recurring Themes

Throughout the strip there are many recurring themes. Most of them are the product of Calvin's incredible imagination and are nothing more than imagined fantasies where Calvin escapes from reality. But others, like Hobbes, apparently have a dual nature that borders on the real and the unreal.

Folding boxes

Throughout his history, Calvin has had numerous adventures using folding boxes (cardboard boxes with flaps) that he has adapted for various uses:

- Transmographer

- Flying time machine.

- Duplicator (with moralizer included).

- Improving Atomic Brain.

- Secret box for A.S.C.O. club emergency meetings.

- Placed to sell things, such as lemonade or "sincere assessment of your appearance".

Using it as a Transmographer is accomplished by placing the box face down, sticking an arrow next to it, and writing a list of options to transform (to become an unlisted animal, Calvin leaves space below to write the name). He turns the arrow to the desired option and presses a button. The Transmographer then rearranges the chemical composition of the subject inside the box and transforms it into the desired shape (accompanied by a loud zap!). Calvin would later invent a Transmographer out of a simple pistol. of water.

The Duplicator is also a cardboard box, although in this case it is placed on its side. The zap heard when a person was transmogrified is replaced by a "boink", leading Hobbes to say: "Scientific progress does it boink?» ("Scientific progress goes 'boink'?", title of one of the Calvin and Hobbes collections). Calvin tries to clone himself so that his clone will do the chores for him. However, the clone refuses to do any work. Later the clone clones itself up to 5 times and drives Calvin's parents crazy. Finally Calvin deceives them and, changing the Duplicator for the Transmographer (deleting one word and writing the other in the box), transforms them into worms. To prevent something similar from happening again, in a later strip he adds the Moralizer, which only clone the good part of Calvin. "The moralizer must be pretty powerful to find that part for you!" Hobbes says, to which Calvin retorts, "I can easily exploit it!" The result is an educated, obedient, clean and good student boy, who ends up falling in love with Susie. Susie comments, "If it were true (that you're Calvin's good part) you'd be so much smaller." Eventually Calvin, horrified, destroys it making him want to fight him, and the clone could only think of good, so disappears. Hobbes comments: "Another victim of metaphysics."

The Flying Time Machine is the same box, but this time face up. Passengers get on it and put on protective glasses. Calvin's first intention was to travel to the future and steal inventions to patent them in the present and become rich, but he is wrong and ends up in Prehistory. In another later strip he returns to Prehistory to take photos of dinosaurs (his great passion). In another strip he travels to the near future (two hours later) to look for an essay that he has to do. But when he arrives, his "future self" (the one at 8:30) tells him that he has not done it, because he is waiting for his "past self" (the one at 6:30) who has gone to the future to look for it Calvin replies, "Sure, here I am! Where is the newsroom? The Hobbes of 6:30 says to the Hobbes of 8:30: "I think that in the end, nobody will write the essay." "As always Hobbes," replies the other.

Other less frequent uses of the box have been as an Atomic Brain (supposedly it boosts Calvin's intelligence to be able to do a school project) or using it to disguise himself (for example, as a robot).

Calvinball

The other boys' games are dead!They have many rules and you have to count points!

Calvin, describing the calvin.

Calvinball is much better long!

It's never the same!

You don't need a referee or a team!

You know it's great, 'cause I'm in it!

Calvinball is a game played solely by Calvin and Hobbes, alluding disparagingly to organized team games; according to Hobbes: "No sport is more individualistic than Calvinball!" The game first appeared in a three-week storyline in 1990, where Calvin is harassed for not signing up for baseball, signs up, and fails at the tries until he is insulted by the rest of the team and quits (the coach calls him a coward). On one occasion Rosalyn played with them, showing that she is very good at the game. Most Calvin and Hobbes games end in Calvinball.

The only rule of Calvinball is that you can't use the same rule twice. Punctuation is also arbitrary: Hobbes punctuates using expressions like "let's Q to 12" or "oggy to boggy." Equipment may include a volleyball (the official "Calvin ball" or "Calvinball"), a soccer ball, a cricket stick, a badminton racket, various flags, bags, signs, and a toy horse. Other necessary items are a bucket of cold water, balloons filled with water, and various songs and poems. The players wear masks similar to those of The Lone Ranger or Zorro (when Rosalyn asks why they are masked, Calvin replies: "Sorry, no questions about the masks"). Watterson described the rules of the game: "...it's simple, the rules change as you play." athletic ability, where Hobbes routinely outwits Calvin and himself.

The n#34;Calvinball#34; Game Design Employee

As Will Wright comments in the conference and better known as the "Calvin Effect" and taking the game used by the comic strip characters as a reference, it has been used in the world of interactive game design, both tabletop and video games. By means of prototypes and before going on the market, a study can be carried out with "beta" of the projects in development and thus be able to see the approach and tastes directly with the users who are the main sales objective for the games in development. Taking the rules of "Calvinball" original, the test is carried out with the users, giving them free control over the project under development and in this way achieving a more fortuitous result for the correct implementation of rules as well as the particular tastes of each user. It is basically what the players will do with the game without the contemplation of the creator.

Carts and sleds

Calvin and Hobbes frequently take vertiginous descents down the mountain, using a cart or a sleigh (depending on the season of the year), while reflecting on life, death, God and other profound topics. The wagon or sleigh is intended as a way to present the strip more visually dynamic, due to Watterson's dislike of strips that are reduced to mere "talking heads". As they descend they negotiate obstacles, used as parallel metaphors for the conversation ("life gets blurry", Calvin says on one occasion, when the sled picks up speed). Many of their descents end in spectacular crashes against rocks, or falling down ravines, leaving their vehicle destroyed and them bruised; on one occasion, even the sled ended up on fire in the deep snow.

Snowmen and balls

During the winter, one of Calvin's favorite pastimes is snowball fights, often using Susie as his target (although most of the time Susie ends up burying Calvin in the snow). On one occasion Calvin had been saving a snowball for three months, to throw at Susie (who wouldn't expect a snowball in the summer) and missed. As Calvin laments, Susie picks up the remains of the ball and throws it at Calvin's face (in the last panel Calvin can only comment, "The irony of the situation is sickening"). He often teams up with Hobbes in snow fights, but Calvin can't resist attacking Hobbes, always with catastrophic results for the boy. This also happens with water balloon fights.

Calvin shows a lot of talent when it comes to creating snowmen, but usually his creations depict grotesque and gruesome scenes showing snowmen dying or undergoing horrific torture (for example, a snowman committing suicide with a hot pack on his head). head, a snowman cutting another in half, a snow octopus devouring small snowmen, etc). Calvin's creations often elicit outright rejection from his parents. For example, in a strip in which his mother sees how Calvin has created a scene where a doll bowls with the heads of other dolls, Calvin is forced inside the house. Calvin comments to Hobbes, "First he tells me to come out, and now to come in." In a well-known story, Calvin creates a snowman and brings it to life using the power "invested in me by the mighty and horrible demons of the snow". The snowman quickly proves to be evil (reminiscent of Frankenstein) and creates more evil snowmen in what Calvin calls "the attack of the monstrous mutant snowmen", who want to kill him. This story gave the title to the Calvin and Hobbes compilation Attack of the Deranged Mutant Killer Monster Snow Goons. In the end, Calvin sprays them with water at night (when they are supposed to sleep) and freezes them, although his explanations do not prevent his parents' anger and punishment for leaving the house at night.

Calvin believes in the aforementioned Snow Devils as "gods" that control the weather, and that require sacrifices of burnt leaves for a cold and snowy winter. When she talks about it to his father, he comments: "I don't know which is worse, your understanding of theology or meteorology.".

Calvin, unlike Hobbes, sees snowmen as fine art. For Watterson this is a critique of "pretentious art." In his snowmen there are references from Picasso to Duchamp.

Club A.S.C.O.

The A.S.C.O. Club (G.R.O.S.S. in the original) is Calvin's secret club, created for the sole purpose of excluding girls, and especially Susie Derkins. The name is an acronym, referring to Valerie Solana's S.C.U.M., using the initials of AsociationSin C >hicas Obtusas (Get Rid Of Slimy girlS in the original). Calvin admits to Susie that "dull girls" it's kind of redundant since all the girls are of course obtuse, but it's "so that the acronyms mean something".

After an initial attempt at creating the clubhouse in the garage (which ends with the car crashing into the roadside and Calvin and Hobbes running from their home), the final location will be a cabin that Calvin has on a tree (except for the previously mentioned occasion when a cardboard box was used, in the only time the club's bylaws are shown). Hobbes is able to climb up to the little house, but Calvin needs the help of a rope, causing Hobbes not to drop the rope until Calvin says the password: eight lines in praise of tigers. Calvin and Hobbes are the only members of the club, each bestowing multiple titles and ranks while crowned with paper hats (Calvin is Dictator for Life while Hobbes is President and First Tiger). The club has an anthem, but most of its words are unknown to outsiders, being written in a code known only to them. Calvin often awards promotions, promotions, or badges for valor. Most of the club's schemes involve trying to annoy or attack Susie, though they almost always end in failure. Like the incident where they try to drench Susie with a water balloon, and end up kidnapping her doll and holding a ransom note; Susie's response will be to kidnap Hobbes and it all ends with a hostage exchange. Another example is coming up with a plan to attack Susie with snowballs while they escape with her sled; This entire plan is shown on a piece of paper that Hobbes is drawing, in the last panel Calvin is seen sitting on her sleigh saying, "Well, if it snowed now."

The Noodle Incident

The famous "Noodle Incident" has never been fully explained by Watterson, but the fact that Miss Woodworm knows about it suggests that it happened at school. Calvin made up an excuse that he impressed Hobbes, but the fact that he got caught shows that no one believed him. Hobbes often alludes to this explanation, arguing that it is worthy of a Pulitzer. The fact that Hobbes or Santa Claus resorted to this case for years suggests that it must have been very serious. The police and other emergency services were involved in an incident, not specified by Watterson, which could be the "Noodle Incident":

- Calvin: Boy, I've gotten into school today.

- Hobbes: What has happened?

- Calvin: I don't want to talk about it.

- Hobbes: Does it have anything to do with those sirens that were heard at noon?

- CalvinI don't want to talk about it!

As has been said, Hobbes sometimes resorts to this incident:

- CalvinThis is the worst job I've ever been sent! I'm supposed to invent a story, write it and illustrate it for tomorrow! Do I look like a writer? It's impossible!

- Hobbes: And what about your explanation of the "Incident of the noodles"?

- Calvin: That was no story! It was the pure truth!

- Hobbes: Oh, don't be modest. You deserved the Pulitzer.

Santa Claus also makes an allusion to the case on Christmas Eve 1995 in Calvin's dream, calling the boy after the "noodle incident kid". One of the elves explains that "the boy claims he was tricked... we've had trouble verifying it, testimonies vary." When questioned about it, Calvin usually replies, "No one can prove I did it! ». On one occasion there was also mention of an "incident with a salamander" to which Calvin claimed: "Temporary insanity! That was it!".

Books

In English

18 Calvin and Hobbes compilation books were published between 1987 and 2005. These include 11 Collections (compiling approximately a year's worth of strips in "square", the first installments, or horizontal the last four) that compile all the strips that appeared in the newspapers, except the one that appeared on November 28, 1985 (the strip of that date that appears in the Collections is not the one originally published that day. The alternative strip, a Hobbes joke while taking a bath in the washing machine, circulates on the internet). The next six books were published under the Treasury format, in vertical format and each one includes the material of two Collection (that is, two years of strips, excluding some) more some unpublished pages in the form of an illustrated story that is included at the beginning of the volume and color reprints of the Sunday strips; there are three Treasuries, which collect the first six Collections.

The Complete Collection of All Calvin and Hobbes Strips was published October 4, 2005, in three hardcover volumes totaling 1,440 pages, by Andrews McMeel Publishing. Includes color prints of how the paperback covers were made, stories and poems added to the Treasuries, and a new introduction by Bill Watterson. Notably, however, the 1985 alternate strip is again omitted, and two strips (January 7, 1987 and November 25, 1988) have dialogue altered for being "politically incorrect." To celebrate this release, Calvin and Hobbes was republished in daily strips in newspapers from Sunday, September 4, to Saturday, December 31, 2005. Apart from that, Watterson answered a dozen selected questions submitted by readers.. Like other reprint strips, the weekday strips were in color (whenever possible), unlike the previous period when they were black and white (only the Sunday strips were in color).

An official textbook for children, titled Teaching with Calvin and Hobbes (Learning with Calvin and Hobbes) was published in a limited edition in 1993. The book includes several Calvin and Hobbes strips with lessons and advice for children. The book is an almost unique object, and highly sought after by collectors.

In Spanish

Ediciones B published the entire series of Calvin and Hobbes between 1997 and 2001, albeit disorderly, in the Fans collection (from 1 to 16 in landscape format, from 17 to 30 in vertical format). Approximately 60 pages correspond to more or less half of an original Collection. The covers are nothing more than enlargements of some drawing of the album.

These 30 issues of the Fans Collection were compiled into 8 hardcover volumes (4 landscape and 4 vertical), respecting the same content, the same album size, the same pagination and the same covers as the original American edition. Combining both formats (Collection and Treasury) Ediciones B has published in Spain all the available material on Calvin and Hobbes. The correct chronological order of these 8 volumes of Ediciones B would be: 7, 6, 5, 8, 2, 3, 1 and 4.

There is also a volume 9 that contains a selection of Calvin and Hobbes strips already published in the other volumes (which corresponds to the Tenth Anniversary Book), with the particularity that they are selected and commented by the author himself. It also includes a broad and interesting introduction in which Watterson comments on details and curiosities about his work.

Finally, there is volume 10 that contains a selection of Sunday pages in a bilingual edition with the original facsimiles in English and the colored ones in Spanish.

Contenido relacionado

Shinji ikari

Martin Luis Guzman

Life is Beautiful