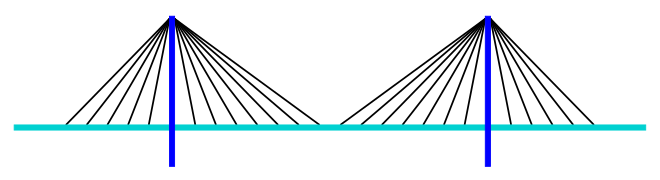

Cable-stayed bridge

A stayed bridge, in civil engineering, is a bridge whose deck is suspended from one or more central pylons by shrouds. It is distinguished from suspension bridges because in these the main cables are arranged from pier to pier, supporting the deck by vertical secondary cables, and because suspension bridges work mainly in traction, and cable-stayed ones have parts that work in traction and others in compression.. There are also variants of these bridges in which the stays go from the deck to the pillar located on one side, and from there to the ground, or they are attached to a single pillar like the Alamillo bridge in Seville.

History

The first tests

The oldest known design for a cable-stayed bridge dates back to 1617 and was published in Venice by Fausto Veranzio, a local scholar, in a collection Machinae Novae Fausti Verantii siceni. It shows a wooden platform supported by iron chains suspended from the towers located on each of the two banks. This type of bridge is also found in Africa, with braces made of liana, and in Asia, with bamboo braces.

The first cable-stayed bridge built dates back to 1784 and was designed by the German Carl Imanuel Löscher (1750-1813). It is 12 m long and made of metal and wood.

Two British engineers, James Redpath and John Brown, built the King's Meadows Bridge pedestrian walkway over the River Tweed in 1817, which had a cable-stayed span of 33.6 m of light. The stays were cables anchored to cast iron pylons. A system of inclined chains was adopted in 1817 for the Dryburgh Abbey Bridge over the Tweed. It had a span of 79.3 m. It had already been observed that pedestrian traffic on the bridge caused vibrations that could easily dislodge the chains. The bridge was destroyed by a strong gale.

In 1821, it was the architect Poyet who proposed building a deck suspended from towers using iron bars placed in a fan shape. In 1823, the engineer and mathematician Henri Navier (1785-1836) studied this type of bridge with inclined chains.

In 1824, the German architect Gottfried Bandhauer (1790-1837) built a cable-stayed bridge to cross the Saale River at Nienburg. Its central light was 78 m; with a major arrow, he collapsed under the weight of the crowd. Motley built another cable-stayed bridge at Tiverton in 1837 and Hartlley, in 1840, built a parallel stay bridge. At the same time, the Manchester Ship Canal Bridge with fan-shaped stays was installed. In 1843, Clive proposed an original fastening system, a mixture of suspension cables arranged in parallel and in a fan.

In 1858, Rowland Mason Ordish, together with William Henry Le Feuvre, took out a patent on a cable-stayed suspension bridge system. It was implemented on the Franz Josef Bridge in Prague, and then on the Albert Bridge in London.

First drawing of a dull bridge of Fausto Veranzio (ca. 1595/1616)]

Bamboo bridge with pullers, in Java.

bridge of the Niagara Falls (1851-1855)

The bridge of the chains of Francisco José I (1885), in Prague (demolished in 1949)

Isolated achievements (end of the 19th century - beginning of the 20th century)

Many of the first suspension bridges included cable-stayed constructions, such as the Dryburgh Abbey footbridge of 1817, Sir James Dredge's patented Victoria Bridge in Bath (1836) and the later Albert Bridge in London (1872) or the of Brooklyn (1883). Its designers discovered that the combination of both technologies created a more rigid bridge. An example of this is the Niagara Falls Bridge built by John Augustus Roebling (1806-1869).

One of the first bridges of the modern type was Albert Caquot's concrete deck cable-stayed bridge of 1952 over the Donzère-Mondragon canal at Pierrelatte, but it had little influence on later development. The most often cited as the The first modern cable-stayed bridge is the steel-deck Strömsund Bridge designed by Franz Dischinger (1956).

The oldest and best-known example of a true cable-stayed bridge is the Bluff Dale Steel Bridge, located in Bluff Dale (Texas, United States), built in 1890 by E.E. Ruyon. In the middle of the XX century, the most pioneering examples include Albert Gisclard, with the Cassagnes bridge (1899)., in which the horizontal component of the cable force is offset by a horizontal strut cable, thus preventing significant compression of the deck.

The system was associated with that of Leinekugel Lecocq's console bridges on the Lézardrieux bridge in 1925 in a rather complicated system. The following year, Eduardo Torroja, a Spanish engineer, designed and built a cable-stayed bridge for the Tempul aqueduct near Jerez de la Frontera; to avoid supporting a pile in the river, he raised the central span of 17 to 34 m and relieved the weight with two sets of cables that he suspended from the bollards. He then obtained the desired tension by activating jacks placed under the cable passage at the top of the bollards.

But these were isolated achievements.

The Cassagne Bridge (1899)

Lézardrieux Bridge

The boom (1952 to today)

The actual study of cable-stayed bridges dates back to the early 1950s. German engineers or even Japanese engineers (Wakato Bridge) are generally credited with authorship, which seems inaccurate considering the dates.. Fritz Leonhardt dates the study of the crossing of the Rhine in Düsseldorf in 1952 with three works from the same family based on an idea by the architect Friedrich Tamms: Nordbrücke, Kniebrücke and Oberkasseler Rheinbrücke, but the realization took place later.

Franz Dischinger built the Strömsund Bridge in Sweden in 1955, which is generally considered the first steel cable-stayed bridge. This was followed in 1961 by the footbridge over Schiller Street in Stuttgart, designed by Fritz Leonhardt, and by the Leverkusen (1965) and Bonn-Nord (1967) bridges, works by Hellmut Homberg. But Albert Caquot was faster and would build a new cable-stayed bridge with a concrete deck over the Donzère-Mondragon canal, the Donzère-Mondragon bridge in Pierrelatte in 1952, which can be considered the first modern cable-stayed bridge, but still with a great influence of previous designs.

Other key pioneers at that time were Fabrizio de Miranda, Riccardo Morandi and Fritz Leonhardt. At this time very few cables were used, as in the case of Theodor Heuss's bridge in Düsseldorf in 1958. However, the use of just a few cables greatly increased the construction cost, which is why modern bridges have many more cables. Time has made cable-stayed bridges make a place for themselves in bridge design and displace cantilever bridges.

Since that time, many cable-stayed bridges have been built around the world.

Strömsund Bridge (1956)

Severin Bridge on the Rhine River in Cologne (1959)

Kniebrücke on the Rhine, in Düsseldorf (1969)

Duisburg-Neuenkamp Bridge over the Rhine, in Duisburg (1971)

General characteristics

Cable-stayed bridges occupy a middle ground between counterweight steel bridges and suspension bridges. A suspension bridge requires more cables (and more steel), and a counterweight bridge requires more steel for its construction, although from a structural point of view they would be bridges that work in counterweight mode.

This type of bridge is used in medium and large spans with spans ranging from 300 meters to a kilometer, such as in straits and bays, although for spans greater than one kilometer, currently only suspension bridges are used. If the designer considers it and the underlying conditions allow it, cable-stayed bridges with successive spans can be built that span spans greater than one kilometer, as is the case of the Río-Antirio Bridge or the Millau Viaduct. This type of bridge is also used for small pedestrian walkways.

One of the characteristics of these bridges is the number of pylons: there are bridges with only one or several, the most typical thing is that they are built with a pair of towers near the ends. They are also characterized by the shape of the pylons (H shape, inverted Y, A, A closed at the bottom (diamond), a single pile...), and whether the stays are attached to both sides of the pylons. the track, or if they support it from the center (two bracing planes or one, respectively). The arrangement of the stays is also characteristic, since they can be parallel or convergent (radial) with respect to the area where they are attached to the pylon. They can also have a large number of closely spaced braces, or few and far apart, as in older designs.

Some bridges have the same cables in the pillars in the central span of the bridge as in the end spans, others have more cables in the center span than in the end spans, also known as compensation spans.

Some cable-stayed bridges are mixed bridges, with some cable-stayed spans and others of the beam bridge type, as is the case of the Rande Bridge.

Comparison with suspension bridges

Cable-stayed bridges, especially if they have several towers, can be very similar to suspension bridges, but they are not. In construction, in a suspension bridge many small diameter cables are arranged between the pillars and the ends where they are anchored to the ground or a counterweight. These cables are the primary load-bearing structure of the bridge. Then, before assembling the track, cables are suspended from the main cable, and later it is assembled, supported by said cables. To do this, the track is raised in separate sections and installed. The loads of the track are transmitted to the cables, and from this to the horizontal cable and then to the pillars. The end weights receive a large horizontal force.

In cable-stayed bridges, the loads are transmitted to the central pillar through the cables, but when they are inclined, they are also transmitted through the section itself to the pillar, where it is compensated with the force received on the other side, not with a counterweight at the end. Therefore, they do not require anchors at the ends.

- Different types of bridges

Pendant bridge

Tired bridge, fan design

Ripped bridge, maple design

Variants of cable-stayed bridges

Side pylon cable-stayed bridge

In this type of bridge, the pylon is not located in the same plane as the runway (longitudinal), but rather a little to one side. This design allows bridges to be built with somewhat curved tracks.

Asymmetrical cable-stayed bridge

This type of bridge uses a pillar at one end of the bridge to which the cables reach. These bridges are not very different from normal cable-stayed bridges. The force of the cables can be compensated by continuing them to some counterweights on the ground. The cables can be replaced by pressed concrete pillars working under compression.

Counterweight pylon cable-stayed bridge

It is a bridge similar to the previous one, except that the cables do not continue to the counterweight, but are anchored to the pylon, and the pylon supports the force of the cables, due to its own weight and its anchorage in the ground. One of the pioneers of this design is Santiago Calatrava with the Puente del Alamillo in Seville.

Historical evolution of the longest cable-stayed sections in the world

This list tries to track the bridge with the longest stretch of the main stretch over time; it may be incomplete since the detailed sources of pre-modern atirant bridges are not always available, so chronology may not be accurate.

![Primer dibujo de un puente atirantado de Fausto Veranzio (ca. 1595/1616)]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f4/Pons_ferrevs_by_Faust_Vran%C4%8Di%C4%87.jpg/278px-Pons_ferrevs_by_Faust_Vran%C4%8Di%C4%87.jpg)