Bullfighting

The bullfighting (from the Greek language ταῦρος, taūros 'bull', and μάχομαι, máchomai ' lugar') is defined by the RAE as 'the art of fighting bulls', both on foot and on horseback. Its antecedents go back to the Bronze Age. Bullfighting brings together the concept and rules that define the art of fighting or bullfighting, an art that was born in Spain of which there is evidence in the 18th century. XI with the celebration of bullfights in Ávila and Zamora in the XIII. The best-known form of bullfighting is bullfighting, the most modern expression of which emerged in the XVIII. The Bullfighting is also the name given to the works or books that deal with it and in which said rules of the bullfighter.

Bullfighting in its different modalities is present in Europe, where bullfights are held in Spain, Portugal and in some departments in the south of France. In Latin America, bullfights are held in Peru, Mexico, Colombia, Ecuador, Venezuela. In other countries such as China, the Philippines and the United States, bullfights have also been held but in smaller numbers. In other parts of the world there are other types of bullfighting such as the Tica bullfights or Fiestas de Zapote in Costa Rica, the Jallikattu also known as Eruthazhuvuthal or Manju Virattu that is practiced in Tamil Nadu (India).

Bullfighting includes, in addition to all those shows related or linked to the bull, the set of traditions, festivals and popular celebrations with the bull as the protagonist. These activities range from the breeding of fighting bulls by bullfighting farms, bullfighting techniques and those activities directly related to it, such as making bullfighting clothing for both bullfighters and banderilleros and picadors, crutches, bullfighting capes, brega and saddlery. It also includes the graphic design of the bullfighting poster and other cultural manifestations around the world of bullfighting such as literature, the plastic arts with their variations depending on the places where they are produced and that are part of the national culture.

Bullfighting originates from Spain and dates back to the Bronze Age, where only royalty was worthy of demonstrating their bravery in front of a bull, contrary to what is believed, rejoneo is the oldest expression, the writings date from the year 1455 in Spain. And this would not be possible without the fighting bull. These stories are intertwined in such a way that it is believed that the first confrontations were with the aurochs, game animals that despite not being an endemic breed of Spain, it was there where one of the largest settlements was found.

Definition of bullfighting by the RAE

The Dictionary of Authorities published between 1726 and 1739 had a total of six volumes and its prologue was entrusted to Juan Isidro Fajardo, councilor of Madrid and official of the Secretary of the Office of the Treasury. The making of the entries for the letter Té of the dictionary (sixth volume) was entrusted to Jerónimo Pardo as he did not carry out the order, the work was entrusted to José Cassani in 1728 and to Lorenzo Folch Cardona who left it in 1730. It was Lope Francisco Hurtado de Mendoza y Figueroa who, on April 22, 1732, finished the mottos between the ta and the te, which did not include the voice bullfighting. The motto bullfighting was not included until 1817 in the definition of 'the art of fighting and killing bulls', and it appeared in the fifth edition of the Dictionary of the Castilian language by the Royal Spanish Academy where the definition of art was also included as: 'set of precepts and rules to do something well&# 39;.

History

Antiquity

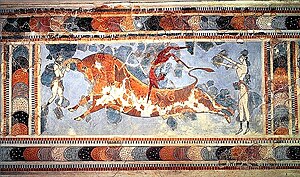

The history of rituals with bulls dates back to the Bronze Age. In ancient cultures, the bull has been an important symbol as an identifying element of rites and animal sacrifices whose purpose was to promote the strength of warriors or the fertility of cattle; Its use in offerings, funeral ceremonies or rituals of passage was also frequent. There are vestiges of these ancient traditions from cultures such as Indo-Iranian, Mesopotamian, Egyptian and European, among all of them those referring to the Iberian Peninsula are relevant due to their direct relationship with bullfighting traditions that led to bullfighting or bullfighting, cultural traditions that were later taken to other countries, such as Portugal, France, Mexico, Peru, Colombia, Venezuela or Ecuador – where their own traditions are maintained.

The vestiges of the Balearic Islands show findings of the Argaric type and of the Talayotic culture similar to those existing in Crete where cults of the bull took place. From the Bronze Age period are the bull heads found in Costig (Palma de Mallorca).

Celtic Culture

For the Celts, the bull was the representation of strength and virility according to the different testimonies of mythology such as the Irish Tarbhfhess ceremony —also known as the Bull's Dream Festival— or the from the Gathering of the Oak Mistletoe described by Pliny the Elder.

Diodoro Sículo recounted how, between 140-139 a. C. Numancia had to pay a tribute to Rome in order to maintain peace with the empire, among other goods included 3000 oxen skins from Celtiberian herds. The bull was also an important element in Celtic funerary offerings and in the plastic representation, where the bulls or boars found next to stelae such as that of Clunia stand out, in which a bullfighting scene is represented in which a warrior fights with a bull.

Tartesian culture

The findings of numerous artistic pieces in the Iberian Peninsula related to rituals and ceremonies with the bull are numerous and are found in practically the entire peninsular geography, however the most important of all these findings is that of the Necropolis of Medellín (Badajoz), specifically, it is an ivory plate that belonged to a funerary trousseau dated between 650-500 BC. C. On the Syrian-style plate a bullfighting scene from Phoenician mythology is represented, it is the hero Melqart who, with a genuflexing knee, points a bull in the head. The piece is related to other similar ones from other Mediterranean cultures such as the Hittite, Syrian or Cretan from the XIII century B.C. C. The importance of the finding lies in the relationship between the cults of the bull and the different civilizations where they took place, including that of Tartessos, in the surroundings of the ancient city of Gadir, also verifying the presence of the bull on the peninsula Iberian as well as the relationship that these ancient rites have with the bullfighting and bullfighting festivals.

Greek Culture

In the bullfighting tradition of Greek culture, one of the best-known myths is that of King Gerión who, as José María de Cossío explains: «... he had herds of bulls and cows in the Iberian Peninsula...” cattle that grazed next to the Guadalquivir river, in Bética, where the first Andalusian cattle ranches and encastes arose centuries later. Although it is not the only indication of rites and celebrations with bulls in ancient Greece, in the findings of Mycenae shows various scenes, in stucco, of jumping over bulls, including some women in front of bulls in an attitude of charging.

Descriptions by Pliny and Seuterius detail bull games during the V century B.C. C. in which horsemen chased the cattle until they reached them and then knocked them down by taking them by the horns. Games that lasted for four centuries. A form of sacrificial bull-baiting took place in the eastern Mediterranean, and Haloa festivals, similar to bullfighting, were held in Athens to honor Dionysus. It was these games that Caesar imported to Rome from Thessaly.

Carthaginian culture

Some clues reveal the use of the bull in war, one of the few testimonies is narrated by Polybius about the war campaigns of the Ager Falernus carried out by Hannibal in Falerno. The Carthaginian made use of Iberian mercenaries accompanied by some two thousand bulls that carried flaming branches on their antlers to make their way between the enemy lines. Regarding this strategy, Diodoro stated that Amílcar Barca had used it in the Heliké disaster —about 'Heliké' historians disagree about the location of the ancient city—where the general died. Following the explanations of José María Cossío, these two testimonies are associated with the origin of festivities such as the embolado bull, which are still celebrated in festivals in Spain.

Roman culture

In ancient Rome, the celebrations of festivals with bulls were introduced by Julius Caesar upon his return from Thessaly where they were common, these activities were represented on Roman coins. The festivals were announced on posters to the public and were celebrated in the amphitheaters where you could see the fighters, including some women.

Some of these festivals were held between the IV century B.C. C. and the I century d. C. as part of the celebrations in honor of Mithra by the Roman legionnaires as indicated by the historian Duris, under the name Taurobolios. These indications are related to bullfighting festivities and some rites performed in Hispania. Among the many antecedents of these rituals are the Taurobolio of the archaeological site of the Roman villa of Arellano known as Villa de las Musas, and that of the founding of the colony Iulia Augusta Faventia Paterna Barcino (Barcelona) founded in 12 a. C. by Octavio Augusto to house the ritual celebrations of the Taurobolios.

According to the study by Pedro Sáez, antecedents of these traditions with bulls can be found in the damnati ad bestias in the time of Emperor Nero, in which Christians were thrown during public executions carried out in the time of their persecution. However, bullfighting shows in the times of the Roman Empire also incorporated fights between wild beasts with confrontations between bulls, bears, panthers, elephants, among other wild animals. The most frequent activities were pole vaulting, mentioned in the Justinian Code as Contomonobolon, as well as taurcatapsia or taurokathapsia, a clear antecedent of bull jumping. bull with the garrocha, a kind of bullfighting carried out in the XVIII century in Spanish bullrings.

Middle Ages

At the beginning of the Middle Ages, documented testimonies around bullfighting indicate that bullfighting festivals and games were already established in the Iberian Peninsula from ancient rituals with bulls in which different ways of mocking bullfights were practiced. the cattle.

Information on bullfighting during the Visigothic period and in the early days of the Umayyad Caliphate is scarce. José María de Cossío in Los toros, volume I, commented on the existence of bullfighting activities based on a letter dated in the year 618, published in volume VII of España Sagrada, from King Sisebuto to the Bishop of Barcelona Eusebio where he questioned his love of bullfighting. This letter was compiled by José de Vargas Ponce in the work Dissertation on bullfighting in 1807.

Other references to bullfighting are those held in Oviedo on the occasion of the convocation, by the Asturian king Alfonso II the Chaste, of the Cortes in the year 815, information collected in the Chronicle of Alfonso X . To these references are added those of the royal bullfighting festivities of the year 1080 in Ávila, celebrated for the betrothal of the infante Sancho de Estrada with Doña Urraca de Flores. From the century XIII there were festivals in which bullfights were run in Castilla, León, Navarra, Aragón, Asturias and Galicia as recorded among the theme poems oldest bullfighting The drunken clergyman, included in the work The miracles of our Lady by Gonzalo de Berceo, and the anonymous work Cantar de los siete infantes de Lara where the wedding of Doña Llambla is narrated, which was celebrated with bullfights. The Siete partidas of King A also date from this period lfonso X of Castilla by which the matatoros were prohibited from fighting bulls for money.

In 1215, according to the guidelines established in the Fourth Lateran Council, the attendance and participation of the clergy in these events was prohibited, however, the festive custom of running the bulls continued to be practiced in different locations. This custom had its origin on the one hand in the adoption of some rites associated with fertility, which is why it was frequent to run and fight bulls in the betrothal celebrations, an example is recounted in the Cantigas de Santa María (1280), songs XXXI, XLVIII and CXLIV. In CXLIV a nuptial bullfight is represented, a Palencia tradition from the XIII century in which a bull was run by the groom to the bride's house wearing a cape to attract the res.

On the other hand, during the XIII century, spearing knights on horseback arose that mocked different beasts as training exercises for both exercise the mounts as for the practice of military exercises. Votive bullfights celebrated on the occasion of the promises or favors requested by some of the participants were also frequent, there is data on this type of celebration in Salamanca. The church linked these practices of festivals and bullfighting to ancient pagan rites in such a way that they gave rise to later prohibitions. With these practices, most of them were public, they obtained the necessary skills for battles during the reconquest. For the knights of the nobility, these exercises consisted of tournaments, games of rods and rings, in which fights with bulls were offered, whose objective was to master the bravery of the bull, a challenge for noble knights and participating monarchs. These practices gave rise, on the one hand, to the fight on horseback or bullfighting, and on the other, to popular bullfighting festivities: running of the bulls and bullfights, bases of bullfighting.

During the Middle Ages, bullfighting festivities took place in public squares, suitable for festivities, to entertain kings and nobles on their visits to Spanish cities on the occasion of weddings, births and royal birthdays or commemorative celebrations. They were fans from Louis VII of France, Alfonso VI, Alfonso VII, the Navarrese king García Ramírez or Pedro I. Less clear are the statements made by Nicolás Fernández de Moratín in the Historical Letter on the origin and progress of the festivities de toros en España (1777), where Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar is credited with being the first to spear bulls on horseback, these statements were disputed by Ramón Menéndez Pidal, who was director of the Royal Spanish Academy and by the Count Colombí, who was president of the Union of Bullfighting Bibliophiles in several letters collected by José Alameda in his work El hilo del toreo, where it is concluded that although the information could have been given, it could not be verified, through documents, that the Cid speared bulls.

Pascual Millán in The Bullfighting School of Seville, collects information about a bullfight held in Pamplona in 1385 ordered by Carlos II of Navarre, for which two bullfighters from from Zaragoza and they were paid fifty pounds; the information was found in the accounting documents of the Royal Collegiate Church of Roncesvalles. In 1387, during the reign of Juan I of Aragon, the first bullfight in Barcelona took place in the Plaza del Rey, as officially recorded in the General Archive of the Crown of Aragon, which is located in Barcelona.

Modern Age

15th century

Since the XV century, references to bullfighting have become more frequent. The celebration of different types of festivals, religious or not, played an important role in this period in the social coexistence of the XV century, at which time models of festivities arose within the nation concept that emerged among merchants residing outside the kingdom. Some of these celebrations in which the entire community participated were sometimes detrimental to certain interests, which is why they arose different local regulations by the clergy. The nobility included among the celebrations and festive banquets fairs, games and bullfights that were held in the cities in order to flaunt their position. These celebrations also fulfilled the social function of uniting the community.

There is evidence of bullfights carried out in Seville on the occasion of the visit that Enrique III made to the city in 1405; In Toledo between 1431 and 1432 on the occasion of the return of Juan II of Castile from the battle of Andalusia, bullfights and jousting were held in the Plaza de Zocodeñe, later known as Zocodover, these were the first bullfights held in Toledo. The visit of Enrique IV to Madrid in 1469 was also an occasion celebrated with bulls in the Royal House of El Pardo, attended by the ambassadors of France and England. In 1492, on the occasion of the celebrations of the capture of Granada, bullfighting festivities among other acts.

The organization of bullfights that were already fought by bullfighters on foot, had significant costs since it was necessary to adapt the streets and squares with fences and decorate them for the occasion. The council was in charge of acquiring the cattle, which imposed reservations on the local butchers. In some Castilian cities such as Valladolid or Palencia, the delivery of the bulls was mandatory and the butchers had to deliver them or have them available for festive celebrations at any time. In 1490 the opposition to the free delivery of the cattle by the Segovian butchers caused the community to have to pay, from then on, the cost of the bulls to the butchers. The amount of the cattle came to account for more than half of the total budget of the festivals in Seville between 1453 and 1526, each of the animals had a cost of between 3,000 and 4,000 maravedíes. In the minutes of the town halls, the accounts, those in charge of the organization, the names of the tools to deal with and the locations where the celebrations are held were recorded.

Starting in the 15th century, the nobility had abandoned the rejoneo to make way for bullfighters on foot, who fought in specific closed venues, which meant a greater risk for the fighters and an increase in the public's demand for the value that the bullfighters had to show. These changes began the journey towards professional bullfighting that will reach contemporary times. In 1554 this new concept of fighting was already known as a bullfight. Impressed by the risk that bulls posed to the fighters, Isabella I of Castilla, la Católica, ordered that the bulls' horns be they were sheathed in others so that they could not hurt the bullfighters, the measure did not prosper due to the difficulty of sheathing the bulls. In 1554 the new concept of fighting was already known as corrida de toros and appears as such in the publications of the time.

16th century

From the XVI century, the process began that formed the classic bullfighting at the hands of the new bullfighters, this process it lasted until the 17th century, to be definitively consolidated in modern bullfighting, in the XVIII Luis Zapata in his work on the values and social behavior of his time, Miscelánea (o Varia Historia) (1583-1595), mentions how the people slowly took over the festival, displacing the nobility until they took away the leading role in the XVIII century. Zapata also wrote the treatises Excelencias de la Gineta (sic.), Use of the rejón and Warnings on the method of running canes, of which of which no copies are preserved, except for the references s included in the Spanish Historical Memoriall of Pascual de Gayangos. In Zapata's study, Emperor Carlos I is described spearing bulls in Toledo and Valladolid; and it is known that he speared a bull in the celebration of the birth of his son Felipe II in 1527. Whoever was a courtier of the emperor Pero Ponce de León, brother of the first Duke of Arcos, performed on several occasions before the royal family in Ávila, in Medina del Campo and in Seville, where he held feuds and accompanied with mulatto pages to assist him during the fight, Ponce de León used the cape to outwit the bull, he was one of the best-known bullfighters in Renaissance Spain and an innovator of the spearing technique waiting for the bull on a horse with the blindfolded, which he diverted a couple of steps to the left during the bull's charge. His grandfather the Marquis of Cádiz had already organized the fight of several bulls in front of the Rota castle on the occasion of the visit of the Catholic Monarchs. He did the same in the square located in front of his house in what was later the convent of La Encarnación in Seville. His fondness for the Muses is attested by the education he provided to his children, the poet Luis Ponce de León and the humanist Gonzalo Mariño de Ribera y Ponce de León, and the one that Juan de Quirós, the best Sevillian poet of the time, gave him. dedicated a poem in Latin, of which we only know the first three verses copied by his disciple Benito Arias Montano.

Another piece of information provided by Zapata in his study is the mention of the existence of the name of the bulls prior to the XVIII century, data from Zapata mentioned by Ignacio R. Mena Cabezas in Knights, bulls and bullfighters in the XVII century.

In the main square of Madrid, two types of bullfights were held: the usual ones, in which the man on foot attended, and the real ones, reserved for select personalities of the Court. The first were organized by the Town Council, the second by those in charge of protocol and Court festivities: Royal Stewardship, and as a general rule they were more luxurious. Popular bullfights used to be held without a fixed date around the dates San Juan (June), in Santa Ana (August), later those of San Isidro (May) and those of San Pedro and San Pablo.

In Seville modern bullfighting arose when the bulls were led through the streets of the city to the slaughterhouse on San Bernardo street, these became confinements in which young men ran in front of the bulls. Before the bulls were sacrificed, the young men used to practice the different lucks and passes in the corrals of the slaughterhouse, an activity that took place at dawn. Next to the corrals, some onlookers and aspiring bullfighters would gather to see how the brave ones outwitted the bull. The presidency of a representative of the municipal authority is also documented. With the passage of time, the spontaneous practice in the corrals was regularly joined by the presence of the public, which is why a small balcony for the civil authorities was attached to it as a tower or box made by the architect Asensio de Maeda and then, in the second half of the XVI century, some stands were built for the public. This first enclosure gave rise two centuries later, in the XVIII century, to the Maestranza bullring.

In the middle of the XVI century, fighting bulls were brought from Navarre to Mexico by order of Juan Rodríguez de Altamirano, owner from the Atenco farm. In the Fifth Letter of Relation that Hernán Cortés wrote to Emperor Carlos V, dated September 3, 1526, the conqueror mentions that bullfights were run and that other sugarcane festivals were held on the occasion of the festivity of San Juan, antecedents that place the beginning of bullfighting in New Spain. The first news of bullfighting in Peru dates back to 1538 with the celebrations of the victory of the battle of Las Salinas, data provided by Ricardo Palma in Peruvian traditions, the same author also mentions that the first bullfight was held on March 29, 1540 on the occasion of the consecration of the holy oil paintings by Bishop Vicente Valverde in which Francisco Pizarro performed.

17th century

The baroque society of the XVIIth century century was above all festive with a predilection for bullfights which were included in the most of the social celebrations, being frequent the use of the main squares and the streets for the development of the same. The society immersed in the religiosity of the time and the inequalities between the nobility and the people found in the bullfighting festivals a form of expression and evasion, in which the danger associated with the risk of death provided emotion and spectacle when running the bulls. bulls in the running of the bulls, when jumping them with the pole, even when fighting them. Valladolid was one of the most important centers of bullfighting during the XVII century, being one of the main Spanish cities, in The Cortes of Castilla were there until 1606, the bishopric of the Court, the University, including the Inquisition and the Second Court together with the Royal Chancery of Castilla—Superior Court of Justice—; found in bullfighting a tool with which to maintain order and avoid social riots while continuing to flaunt power in the hands of the monarchy, the church and some nobles.

Both Felipe III and Felipe IV were fond of bullfighting. Some of the calls became a reason for conflict with the Inquisition because the celebration coincided with festivities in honor of saints such as San Pedro Arbúes. in the royal bullfighting festivals held in the Plaza Mayor in Madrid, attended by the Prince of Wales Carlos Estuardo, future Carlos I of England and Scotland, together with his lieutenant Lord Buckingham during his stay in Spain, repeating later the experience in his country, inviting the ambassadors of the kingdoms of France and Spain[citation required]

“His majesty is so encouraged, that the most days are put on horseback, and neither the snow nor the hail remove him. In Tembleque, the council received his majesty with a bullfighting party, said of alarifes of garn, very valenty of risky toretors, and some successful. Bonifaz looked at him, and nothing was hurting. They had fires on purpose and well executed. His majesty of an archdiocese passed a bull that couldn't tear him apart... ”Francisco Quevedo

The documentation that exists on the wedding between Carlos II and María Luisa de Orleans held on November 19, 1679 in Quintanapalla (Burgos), have provided bullfighting researchers with important information about the celebrations of the same and how the bullfighting festivities were among these. The information on the link and the organization of the different acts was recorded in the Book of Minutes of the Burgos City Council by Joseph Martínez de Araujo, (sessions from August 14 to November 9, 1679, folios: 302r-472v). On the third day of the celebration, a bullfight was organized in the Plaza Mayor of Burgos whose preparations began at dawn with the confinement of thirty bulls in a bullpen in front of the elegantly decorated royal box, and another in the right side of it. Before the beginning of the celebration, the royal bailiffs cleared the square to then start the bullfight in which the knights José de la Hoz and Melagosa fought together with sixteen expert bullfighters from all over the country. Fourteen of the thirty bulls were fought in a celebration that lasted three hours; the rest of the cattle were dealt with the following day. Between the years 1680 and 1690, bullfighting had declined as a result of the significant economic problems that the kingdom was going through, caused by the significant drop in prices or deflation. Economic problems were joined by the insistence of Pope Innocent XI who reminded the monarch of the provisions on bullfighting of Pius V (1567) ignored by Felipe II. Given the new papal request to prohibit bullfights throughout the kingdom Faced with the risk of death of the fighter, the Council of State drafted a report in which it states that the risk faced by bullfighters is not great and therefore there is no sin when these are professionals, however, faced with moral pressure, Carlos II, on June 22, 1682, he suspended bullfights and comedies throughout the kingdom. This suspension lasted a year, since in 1683 bullfights resumed.

The way of fighting on horseback implied that the rejoneadores relied on pawns and squires whose functions consisted of providing the tools to fight, move and place the bull while the knights changed tired or injured horses, or to rescue them from a fall. Another of the functions that the assistants fulfilled was to distract the bull to let the horse out after the embroque and to kill the bull when the rejoneador failed or lost any of the bullfighting tools and had to make the effort on foot.. With the appearance of the varilargueros in the XVII century, replacing the spearing knights and after the latter abandoned fighting, the pawns and assistants were acquiring greater responsibility, until they became the professional fighters or bullfighters of modern bullfighting. On many occasions, if the horseman could not kill the bull, the responsibility was delegated to those on foot.

18th century

The 18th century was the century of the Enlightenment, the bourgeoisie boomed along with secular thought, humanism it replaced religious authority and the ideal of progress. In Spain the Enlightenment began during the reign of Felipe V, continued with Fernando VII and had its peak with Carlos III. With the reign of Felipe V, expenses were cut to alleviate the fiscal pressure on the people, affecting the cuts to religious festivities and bullfights, the Council of Castilla claimed the continuity of the bulls recovering the festivities with the presence of the monarch on April 14, 1701, however it was not possible to hold them in later years until July 28, 1704 in which they were celebrated again on the occasion of the return of the king from the War of succession with Portugal. The situation regarding Felipe V's refusal to make extra expenses was maintained for almost twenty years, a period in which festivities continued to be held in some cities depending on the importance of the event celebrated, for example, the bullfight on July 30, 1725 in Madrid, presided over by the king and queen, where the knight of Pinto, Bernardino de la Canal, mentioned by Nicolás Fernández de Moratín, performed in bullfighting, together with about twenty professional bullfighters.

The town created its own National Festival while the bullfighters became professional and began to have their own fame and followers. This professionalization had an impact on the way bullfighting was viewed by the authorities who tried to protect the town from bullfighting. risks of the fight when considering that a professional was no longer carrying out a reckless act. Given this new vision of bullfighting, the need to regulate and supervise the actions of the new fighters arose, for which a process began to meet the new professionals and the way in which they fought. The names of Francisco Romero, Lorenzo Martínez, Lorenzillo (Sic.); Melchor Calderón, Miguel Canelo or Francisco Benete.

In Seville, two centuries before the creation of the School of Bullfighting, when the bulls were led through the streets of the city to the slaughterhouse on Calle San Bernardo, before the bulls were sacrificed, the young men aspiring to be fighters They used to congregate and practice the different lucks and passes in the corrals of the slaughterhouse, an activity that took place at dawn. Along with these, some curious people began to gather to see how those brave men mocked the bull. The presidency of a representative of the municipal authority is documented as a result of the riots and disorders that occurred as a result of bullfighting practices, the documentation on the actions of the authorities are kept in the municipal archives of Seville. Among the measures adopted over time, and given the need to avoid disorder, together with the usual congregation of the public, a small balcony for the civil authorities was attached to the slaughterhouse as a tower or box made by the architect Asensio de Maeda and later, in the second half of the XVI century, some stands were built for the public. This first enclosure gave rise in the XVIII century to the Maestranza bullring.

By the middle of the century, figures such as Joaquín Rodríguez Costillares, Pedro Romero —son of Francisco Romero—, José Delgado, Pepe-Hillo had made a name for themselves in the world of bullfighting. The first Tauromaquias arose, manuals that included the forms and technical recommendations and rules on bullfighting, the Cartilla published in the XVII, the treatise by García Baragaña and La tauromaquia o arte de torear published in Cádiz in 1796 dictated by Pepe-Hillo.

The majos and manolas arose along with their festivals and bullfighting with bullfighting on foot. Among the real contributions to the promotion of culture and art were the creation of the Academies of History, Language or Fine Arts. Following this line, in 1754, Fernando VI donated to the Royal Board of Hospitals the first bullring built in a brick factory, the Plaza de toros de la Puerta de Alcalá, this replaced the existing one made of wood next to the Puerta de Alcalá that Felipe V had authorized. In addition to the Bullfighting School in Seville, the bullrings of the Real Maestranza in Seville (1761), the Pignaltelli arena in Zaragoza (1764) or the Plaza de la Real Maestranza in Ronda (1785).

Around 1770 the use of rods was consolidated due to the preferences of the public for the use of the rod to stop or long instead of the use of the rejones that was usual in the knights of the nobility. The figure of the varilarguero took center stage as the core of the fight, among the first best-known picadors fought in 1736 in the Seville maestranza the Merchante brothers or José Daza who fought in 1740 author of a treatise on bullfighting both on horseback and on foot.

The pressure exerted by the Count of Arana on Carlos III caused vetoes again between 1778 and 1785. These did not affect public utility bullfights, that is, those whose purpose was beneficial, so that the celebration of bullfights continued to be common. the same.

The manuals on fighting on horseback no longer have the interest of the previous century, in their place arose the Primer in which they are proposed, the rules for fighting on horseback, and to practice this courageous, noble exercise with all dexterity, known as the Cartilla de Osuna by the author Nicolás Rodrigo Noveli (1726), the Rules for bullfighting and art of all luck attributed to Diego de Torres Villarroel, The malice, confused by Francisco Melcón (1738) or Rules of bullfighting on horseback by José Fernández Cadórniga. Essays on value and prudence rules for the arena by Marcelo Tamariz de Carmona (1771). Together with those who wrote the manuals on bullfighting, a number of anti-bullfighting authors arose, such as Father Feijoo, Father Sarmiento, Mayans or Jovellanos, who, despite not being a bullfighter, was an admirer of Pepe-Hillo and attended several bullfights. in Valladolid. These were joined by Vargas Ponce who, on July 13, 1792, wrote to Jovellanos to provide him with information to include in the work Dissertation on bullfighting, written by Vargas Ponce around 1807. Faced with these ideals, they found Nicolás Fernández de Moratín in defense of bullfighting, author of Historical letter on the origin and processes of bullfighting in Spain, (1777), Ramón de la Cruz, Bayeu or Goya, a bullfighting fan and novillero with the crews of Costillares and Pedro Romero. Goya created part of the series of engravings La Tauromaquia inspired by the idea of the possible Arab origin of bullfighting developed in the aforementioned work by Fernán dez Moratín, the Aragonese painter recorded this in the annotations of the engravings.

19th century

The 19th century began with the death in the arena of Pepe-Illo in 1801. Shortly after Carlos IV published through the Royal Decree of February 10, 1805 the prohibition of holding bullfights and steers in which the bull was killed, alleging moral and political causes, however it authorized those charitable bullfights. The royal prerogative was published in the Novísima recopilación de las leyes de España. According to local traditions, as happened in Portugalete on September 12, 1806 on the occasion of the appointment of Justo De Salcedo y Araujo as lieutenant general of the Navy, the celebrations consisted of three days of bullfighting without the cattle being chopped or stabbed. The 1805 decree was repealed when Fernando VII ascended the throne in 1808, celebrating a bullfight in Madrid on September 19 of that year and on September 26 in which José Cándido, Curro Guillén, Juan Núñez, Sentimientos, and Agustín Aroca, who toasted against the presence of French troops. The toast cost Agustín Aroca to be arrested the next day and shot shortly after in the mountains of Toledo.

José Bonaparte sought to win the favor of the people by promoting bullfighting, on June 9, 1810 by means of a Royal Decree the prefects of Seville, Córdoba, Granada, Jaén and Jérez de la Frontera searched for the bulls and the bullfighting gangs to that they fought in Madrid between June 24 and 28, 1810 and on later dates. Among those hired were the bullfighter Teresa Alonso, the bullfighters Lorenzo Jade, Juan Núñez, Sentimientos; Luis Cornacho, Jerónimo Cándido and Curro Guillén who fought accompanied by the pole vaulters Ildefonso Pérez Naves and Jerónimo Martín, Pajarito who had participated in the battle of Bailén together with the so-called Garrochistas de Bailén, a group of ranchers and picadors under the command of José Cheriff. The bullfighters received between 3,000 and 1,000 reales de vellón and the female bullfighter 500 reales. Pedro Romero along with his brother Juan Romero refused to attend the celebration organized by Bonaparte. Among the measures adopted by José Bonaparte to facilitate access to the festival was the change in the schedule of the mass on July 1, 1810 and the creation of bull tickets. During the months of July and September bullfights were held, and in the months of March December 1811, highlighting the one held on December 25, the eve of the announcement of the return to France of José Bonaparte after exhausting the economic resources of the country.

In the middle of the XIX century, the first bullfighting regulations appeared to regulate the festivities that were held in closed bullrings. The new regulations allowed bullfighting to go from being celebrations with local characteristics, according to each town, to being held with a similar format in all cities. Similar precepts were articulated in the publications, such as the conditions that the venues had to meet, the behavior guidelines of the public, the rules for bullfighting and the conditions of the bulls inspected by veterinarians; with small variations between the regulations depending on the locality, the Regulations for bullfighting in Madrid were published, which were approved by the provincial governor on May 28, 1868, and the Regulations for bullfighting performances that are held in this city, published in Cádiz in 1872, Regulations for the bullring in the city of Salamanca published in 1884, the Regulations for the Seville bullring published in 1896, the Bullfighting Regulations published in Malaga published in 1897 or the Actual Regulations for Bullfights written by Leopoldo Vázquez Rodríguez in 1891.

Regarding bullfighting, it experienced a new concept with bullfighters such as Paquiro, Cúchares, Lagartijo and Frascuelo, which changed the way of fighting and the concept of expressing bullfighting. Rafael Molina Lagartijo, a disciple of Antonio Carmona el Gordito, contributed elegance, artistic plasticity and natural line bullfighting or natural bullfighting, that is, the essential concept of modern bullfighting that will last until contemporary times. Natural bullfighting differs from changed or opposite bullfighting, widely used by Frascuelo, due to the way in which the bull is guided, that is, the bull passes through the same side that the bullfighter has The left hand grasps the crutch, while in changed bullfighting the bull leaves the crutch on the opposite side of the hand with which the bullfighter holds the crutch.

20th century

The XX century or the golden age of bullfighting was the moment of Mariano de Cavia, Sobaquillo, journalist and critic bullfighting witnessed the dark times of Spain, a situation that also affected bullfighting. friendship of the French politician with two Spanish bullfighters: la Tartataja and Pepa la Banderillera and for this reason Azorín, a great follower of bullfighting, questioned his real love for bullfighting. Merinée was a great connoisseur of bullfighting, the breeding of the fighting bull and the details of the fight.

During the first decade of the century, Antonio Fuentes, the Mexican Rodolfo Gaona who made Mexican and Spanish bullfighting universal; Rafael González Madrid Machaquito or Ricardo Torres Bombita, Rafael Gómez, Gallo and Vicente Pastor who occupied the top positions in the bullfighting ranks. of bullfighting, starring the professional rivalry between Juan Belmonte and José Gómez Ortega, Joselito, also known as Gallito III. Both right-handers are considered the most important of modern bullfighting: Belmonte, as the creator of modern aesthetics ("stop, temper and command") with which he changed the concept of bullfighting as well as contributing to bullfighting seen as an art of bullfighting, whose purpose was based on the beauty of the whole more than in the fight itself; and Joselito as the complete bullfighter, master of all luck and all aspects of bullfighting, (from the idea of building large monumental bullrings to the details of the selection of the fighting bull), brought together the best of ancient bullfighting and announced the technique that would prevail in the future of modern bullfighting.

Interest in bullfighting increased with new publications of bullfighting content in specialized magazines such as Sol y Sombra with 3000 copies in 1920, the magazine Don Jacinto Taurino, or El Eco Taurino which had a circulation of 8,000 copies. Theatrical performances and zarzuelas also chose to include bullfighting in their repertoires, in the Easter of Resurrection bullfight held in 1902 in Seville, Bombita and Emilio Torres made the paseíllo accompanied by a pasodoble from the zarzuela El Bateo by Chueca. The lyrical farce La Torería by Antonio Paso and Asensio Mas with music by José Serrano. Novels with bullfighting as their main theme were published, such as Blood and Arena (1908) by Blasco Ibáñez or Currito De la Cruz (1921) by Pérez Lugin. One of the first radio broadcasts from abroad was that of a bullfight from the Plaza de Vieja in Madrid held on October 8, 1925.

In bullfighting, new bullfighting figures emerge, such as Ignacio Sánchez Mejías, who was a full stop, with him there is an after of bullfighting, that is, a life outside the bullrings that pierced the intellectual society of the 20th century. Through the vision of Sánchez Mejías, ranchers, writers and poets became interested in bullfighting and bullfighters with another perspective, bullfights went from having a reputation for being crude to having a prestige and an attractive character for the most prominent social circles.. Thus, the presence of Sánchez Mejías in gatherings and social events places bullfights as a reference for literature, poetry, theater, dance or ballet where authors of the stature of Federico García Lorca would focus their works. With Sánchez Mejías, the festival transcends outside the bullring to the point of being linked to Spanish culture, forming a bond that gave rise to the best socio-cultural achievements of the time, including the prose and poetry of the generation of '27.

After the Spanish civil war, there was a revival of bullfighting thanks to the figure of Manolete, the most important bullfighter in bullfighting history; This resurgence was followed by figures such as Luis Miguel Dominguín, the Mexican Carlos Arruza, Pepe Luis Vázquez, Antonio Bienvenida, Pepín Martín Vázquez, Silverio Pérez, Miguel Báez El Litri, Julio Aparicio and Agustín Parra Parrita. This period ends with the death of Manolete in the tragedy of Linares. The stage begins Dominguín and Antonio Ordóñez, great rivals in the arena.

In the 1950s, new concepts of the bullfighter emerged with the Venezuelan César Girón, his brother Curro or bullfighters such as Curro Romero, Paco Camino, El Viti, Diego Puerta, and Manolo Martínez. The bullfighter who most revolutionized this concept was Manuel Benítez, the Cordobés with an unorthodox but forceful idea that led him to fill the bullrings all over Spain where he introduced the concept of social status disagreement. El Cordobés also separated himself from the conditions of the bullfighting industry along with Palomo Linares, in what became known as the year of the guerrillas, in which they claimed to control their bullfighting life, for that season only they fought in second and third category squares; From these demands arose in 1968 the record book of wild livestock and the marking of the cattle with the figure of the year of their birth published in the B.O.E. on December 16.

The decade between 1970 and 1980 saw the greatest commercial expansion in the world of bullfighting, and there were even bullfights at the Houston Astrodome, with the participation of Manuel Benítez «el Cordobés». The great figures of this period are: José Mari Manzanares, Pedro Gutiérrez Moya El Niño de la Capea, Dámaso González, Morenito de Maracay, Francisco Rivera "Paquirri", El Yiyo, Nimeño II, Antoñete and Juan Antonio Ruiz "Espartaco", leader of the statistics consecutively from 1985 to 1991.

21st century

The new figures of bullfighting present great diversity in their style and projection; personalities as particular as Enrique Ponce, and Joselito —of classic bullfighting—; Julián López, el Juli, José Tomás, Manuel Jesús Cid el Cid, Miguel Ángel Perera, Pepín Liria, Morante de la Puebla, José María Manzanares, Alejandro Talavante, Luis Bolívar, Gonzalo Caballero and the Frenchman Sebastián Castella, are some of the bullfighters most famous of the XXI century.

Bullfighting

The Tauromaquia was the name given to the works or books that deal with and compile the different techniques of bullfighting, where the rules of bullfighting are also developed in the form of a manual to be read by bullfighters.

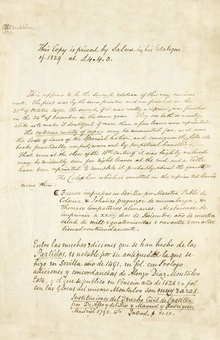

Osuna Primer

The first known Bullfighting was the one known as the Cartilla de Osuna (Cartilla, in which the rules are proposed, to fight on horseback, and to practice this courageous, noble exercise, with all dexterity) published in 1726. Later, García Baragaña published a treatise that included part of the recommendations published in the aforementioned Cartilla de Osuna, Baragaña's work was published in 1750 under the name Noche fantastic, idealistic diversion that demonstrates the method of fighting on foot. This compiles the technique of the cape luck, banderillas, the canvas as a primitive crutch and the use of the rapier, developing for each of them the most convenient forms to perform them; Thus, in the banderillas the luck of (banderillas) to topacarnero known as «a half turn» is mentioned, the author cites the way of placing these to «broken compass» as a kind of relief and details the ways to go in to kill "to receive " which he also calls "luck of the law".

Precise handling and progress of the art of bullfighting

Precise handling and progress condoned in two volumes of the most obligatory peculiar to the art of Agriculture, which is bullfighting, exclusive to the Spanish is a work collected in two volumes, also known as The art of bullfighting, which the varilarguero José Daza wrote between 1772 and 1778, the original copy is preserved in the Royal Library of the Royal Palace. Daza's work was a reference for the works that were published later Fernández Moratín, Pepe-Hillo and Paquiro. The work that was originally distributed as manuscripts through copies and was only partially published, the bullfighting work had its first complete edition in 1959 through the Real Maestranza de Caballería de Sevilla, the Fundación de Estudios Taurinos and the University of Seville.

Treatise on bullfighting by Pepe-Hillo

One of the best-known Tauromaquias was Treatise on bullfighting dictated by the bullfighter José Delgado, Pepe-Hillo, whose writing is attributed to José de la Tixera and was published in 1796 in Cádiz. In the work, the bullfighter gives a series of instructions on how to fight on foot following a strict orthodoxy. Analyzed by different authors, such as Cossío or Fernando de Claramunt, there are various opinions about the treatise directed above all at the difficulty of applying the recommendations given by the well-known bullfighter. Its publication gave way to bullfighting on foot, displacing the fight on horseback, With it the new art of fighting was reinforced and it faced the pragmatic sanction of 1785 that vetoed the death of the bull in public of certain bullfighting festivities. A second edition of Pepe-Hillo's Treatise on bullfighting was published in 1804 in Madrid with important changes clarifying some concepts to the reader. In contemporary times Pepe-Hillo's treatise continues to be a reference manual for bullfighters.

Complete bullfighting of Paquiro

Written by Francisco Montes, Paquiro, and edited by Santos López Pelegrín, Abenamar, the complete Bullfighting, that is, The Art of bullfighting in the arena, both on foot and on horseback: written by the famous fighter Francisco Montes, and scrupulously arranged and corrected by the editor was published in 1836. In the work Paquiro organized a series of precepts and legislation for bullfighters with which the definitive form of bullfighting was established, thereby organizing the way in which men and bull faced each other in the ring. With Paquiro the varilarguero disappears and through complete bullfighting the rules that will govern both picadors and the development of luck are established, as well as the third of rods that was adapted to bullfighting on foot; the banderillero was established as a collaborator of the bullfighter under his orders as Costillares had established with the gangs. Along with the development of these precepts, Paquiro carried out a study of bullfighting, both cape and crutch and banderillas, practiced in his time, so that Pepe-Hillo's Treatise on bullfighting was expanded with their contributions.

Among the contributions to bullfighting that are made from this work, the development of the study of the fighting bull stands out in terms of its behavior and the conditions that it must have to be fought, providing for each type the appropriate instructions for its fight.

Unlike Pepe Hillo's work, Paquiro's is based on the beginning of each one of them, Hillo begins his bullfighting with recommendations for the rejoneo, while Paquiro focused only on the fight on foot as described they carried out the bullfights of that time, revealing the new order of bullfighting in the XIX century.

The Complete Bullfighting by Francisco Montes is considered one of the most important works on bullfighting before the publication of Los toros. Technical and historical treatise known as El Cossío by José María de Cossío published in 1943.

Environment

The environment or framework refers to those elements and social factors that make it possible to understand bullfighting, as well as those activities that make it possible to understand it. These factors include both cultural and traditional, anthropological, historical and ecological elements as well as those that are specific to the activity, such as the breeding and selection of fighting fighting bulls. Bullfighting was declared a Spanish cultural heritage on November 12, 2013; It is a cultural tradition that has its roots in countries of America and Europe. In Spain there are different levels of cultural roots depending on the place, so you can find communities where bullfighting activities are not carried out, such as other areas where bullfighting traditions are known worldwide, such as the Sanfermines.

United from its origins to the ancestral cultural traditions of the Mediterranean, the interpretation of bullfighting has given rise to different forms of artistic and cultural manifestations from literature and poetry to music, cinema, theater or dance among others. Center of numerous festivals and local celebrations, bullfighting is part of the Spanish, Latin American, Portuguese or French traditions, where it is an important economic engine that generates wealth and employment at a national level. Along with bullfighting, it is common for different events and cultural events to be held, such as exhibitions, meetings and colloquiums around the different topics that bullfighting includes.

In addition to bullfighting, bullfighting includes the breeding and study of fighting bulls raised in the pastures, where they live. The meadows represent a rural element of ecological wealth, support of the rural environment and biodiversity of the area in which, in addition to the fighting bull, another important number of species of both flora and fauna are included. The presence of the fighting bull in the Dehesas is of special importance for their sustainability, the bull takes advantage of the resources it finds in its environment in a rational way, while preserving it by limiting access to the farms in such a way that the ecosystem of the dehesa is maintained.

The tailor and the gold thread embroiderer are another of the professions associated with bullfighting in everything related to the making of bullfighters' bullfighters' bullfighting gear: fighting capes, crutches, banderillas, rapiers, etc. Artistic manifestations related to the activity: making posters.

Bullrings

Before the construction of the bullrings, the confinement of wild cattle run through the streets ended up in the local squares set up for the celebration of the festivities and subsequent celebrations. Given the personal damages and damages that were caused during the celebrations, the councils of the affected localities decided to create ordinances to regulate the way in which the acts should be carried out. In Huesca in 1275 it was prohibited that, when cattle were run for reasons of weddings, they were prohibited from entering the cathedral. In Valencia it was prohibited in 1339 to organize impromptu bullfights given the damage and disorder they caused. In Zaragoza, in 1460, Juan II ordered that butchers sell their products outside the city market square, where all the festivities were also held, including bullfights, to avoid contamination of the food sold there, thus arose the need to close the bullring and convert it into a closed arena conditioned for bullfighting.

In 1565 the reform of the Sevilla slaughterhouse was ordered, where the confinements ended and then bullfighting and bullfighting were practiced. The reforms consisted of creating a square with abundant windows from which the Sevillian nobles and other personalities came to see the bullfights that took place on the plains of the slaughterhouse, similar to a closed ring; Said modification is included in the Chapter Acts of February 23, 1581 Law the proposal that Don Diego de Nofuentes made the last council on the haser plaça in which the border of the slaughterhouse is made. Twelve years later, between In 1577 and 1579, the rostrum for those attending the bullfights whose seats were rented was integrated into the complex. During the works, the first existing presidential box was built in a bullfighting arena.

The closed and specific bullrings for bullfighting, also known as cosos , are architectural structures with different styles, according to their age. In general, it is a closed circular enclosure, with lines and services that surround a central space, called the arena or arena, where the bullfighting spectacle takes place. The arena is a field of beaten earth or albero, used in Andalusia, surrounded by a fence of wooden boards or barrier that measures approximately 140 centimeters high, has several mockery in its perimeter, behind which are the bullfighters, the auxiliaries, assistants, authorities and other assistants, behind the burladeros the bullfighters also take shelter. The space between the barrier and the laying is called the alley. The ring has swing access doors for the entrance and exit of the participants (puerta de cuadrilla) and the bulls (puerta de toriles), although the arrangement of these accesses varies from one bullring to another.

The oldest surviving building in Spain is the Béjar bullring La Ancianita dating from the year 1711, it is of the 3rd category and belongs to the Union of historical bullrings. The oldest first-class bullring in Spain is the Plaza de toros de la Misericordia in Zaragoza, dating from 1764. The oldest surviving bullring in America is the Acho bullring (Peru), dating from the year 1766. The largest bullring in the world is the Monumental de México, with an approximate capacity of 41,000 seated people.

Bullfighting and culture

Bullfighting is closely linked to ancestral culture, both traditional and popular. This has accompanied the historical course of the bullfighting festival, so that cultural manifestations related to bullfighting can be found in the plastic arts of artists such as Goya, Picasso, Manet, Enrique Simonet, Alberto Gironella or Lucas Villaamil among other artists; in musical manifestations such as the pasodobles of the Mexican composer Agustín Lara or flamenco among others; as well as in literature, cinema and theater. In Opera, Carmen by Bizet, the most beautiful and performed Opera in the world, is an extraordinary example of this.

Bullfighting is an exercise of multiple understanding, since it can be admired or criticized, but its components, already mentioned, allow it to last over time and generate a wide debate around it. For example, the Spanish government, through the Ministry of the Interior, refers to the cultural aspect of bullfighting in its regulations for bullfighting schools: "To promote bullfighting, in attention to tradition and cultural validity of the same, bullfighting schools may be created for the training of new bullfighting professionals and the support and promotion of their activity."

The philosopher José Ortega y Gasset explained that it was unthinkable to study the history of Spain without considering bullfights. If some of the writers and philosophers of the Generation of '98 did not like bullfights or flamenco, it was because they considered that bullfighting and singing were a backwardness of Spanish society that given the historical and social moment that Spain was living. Thus, Unamuno explained that he did not like bullfights, not because it was a bloody spectacle, but because he spent a lot of time talking about it and this explained the cultural formation of its spectators. However, many others were bullfighting fans and dedicated part of their works to bullfighting. Bullfighting was regularly present in the work of Ortega y Gasset, he was a bullfighting critic, an attorney for bullfighters and a great fan, he even organized celebrations with Zuloaga in which he fought. In La caza y los toros (1962), he was surprised that bullfighting, being a quiet exercise, gave so much to talk about, in the work he made an analysis of the fighting bull and its way of charging related to man himself, an analysis he called. "the compression of the bull".

Later, the Generation of '27 was mostly a party lover, about which they wrote, painted and sculpted. It is worth quoting the words with which Federico García Lorca expressed his open support and love for bullfighting: «Bullfighting is probably the poetic and vital wealth of Spain, incredibly untapped by writers and artists, mainly due to a false education pedagogy that they have given us and that the men of my generation have been the first to reject. I think bullfighting is the most cultured festival in the world».

Antonio Machado was a bullfighting critic together with his brother Manuel in the magazine La Caricature, the poet went through all the stages, he went from being an amateur to rejecting bullfighting to understand it again through his poetry.

Ortega y Gasset, like other authors such as the academic José María de Cossío, made a parallel between bullfighting and the history of Spain:

I affirm in the most taxative way that the history of Spain cannot well understand, from 1650 to this day, who has not firmly established the history of bullfighting in the strict sense of the term, not of the bullfighting party that, more or less vaguely, has existed in the Peninsula for three millennia, but what we now call with that name. The story of bullfighting reveals some of the most hidden secrets of Spanish national life for almost three centuries. And it is not a question of vague appreciation, but, otherwise, we cannot precisely define the peculiar social structure of our people during those centuries, a social structure that is, in very important orders, strictly inverse of normal in the other nations of Europe.José Ortega y Gasset

Other contemporary intellectuals, such as Enrique Tierno Galván, underlined, in open contradiction with those of 1998, the socially pedagogical nature of bullfighting: «Bullfighting is the event that has most educated the Spanish people socially, and even politically». And it abounded in the refinement of artistic taste that it represents for its fans:

The spectator of the bulls is continually exercising in the appreciation of the good and the bad, the just and the unfair, the beautiful and the ugly. The one who goes to the bulls is exactly the opposite of that fan of the shows, of whom Plato says that he does not tolerate them talking about the beauty itself, the justice itself and other similar things. The spectator of the bulls is not a mere, a simple fan of the spectacular, nor exclusively an enthusiast of the intoxicating exaltation, is, better than all this a lover of the whole of which, as an event, is necessary part.The Bulls National EventE. Tierno Galván

A long list of writers from various countries have written exalting bullfighting as an important part of the soul of their peoples. Among the living artists who defend bullfighting are the Peruvian Mario Vargas Llosa, the Colombian sculptor and painter Fernando Botero and the Mexican sculptor and painter Humberto Peraza.

Among the supporters of bullfighting are the painter Francisco de Goya who participates in bullfighting and the writers Nicolás Fernández de Moratín and Valle-Inclán. Philosophers such as Fernando Savater or Enrique Tierno Galván, and artists such as Joaquín Sabina or Joan Manuel Serrat, argue that these criticisms of anti-bullfighting are due to ignorance, since the fighting bull lives in freedom in its natural habitat and, without the bullfights, Not only would the fighting bull become extinct, but also the ecosystem in which it thrives (the pastures), however there are allegations that these can be protected by law without the need to raise bulls. Other defenders of bullfighting, such as professor Andrés Amorós, argue that nobody loves the bull more than a good bullfight fan: «nobody admires its beauty more, nobody demands its integrity more vehemently and is more furiously indignant at any mistreatment, contempt or fraudulent manipulation."

On the contrary, some writers have expressed their disagreement with bullfighting, such as Cecilia Bohl Faber, who signed with the male pseudonym Fernán Caballero to be able to venture into a literary career:

How amazed were the fans of bulls, cults, bunks and liberals, if they knew that the illustrated Germany that so many sympathy has for the homeland of Calderon and Lope, faces Spain simultaneously the bullfighting and the Inquisition.Cecilia Bohl Faber (Fernán Caballero)

Bullfighting in the language

Different philologists have pointed out the strong heritage of the practice of bullfighting that can be seen in the expressions of habitual use both in colloquial levels and in various types of written language, which is due to the historical popularity of bullfighting in very diverse sectors of Spanish society, despite the clear decline in popularity, especially in the youth spectrum. Despite this decline, society in general continues to use these expressions, very often without being aware of their origin. Among them we can mention, for example, "change the third", "full to the flag", "at the first change", "harassment and demolition", "be in the doldrums" "enter the rag", "puncture in bone", "to be quite", "what a task", "to fall from the sign", "to be dragged", "to put the world by montera", "to throw a cape", "to cut the ponytail", "to give the lace", "finish the job", "take the bull by the horns", "see the bulls from the barrier", etc.

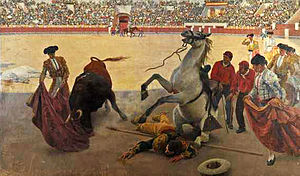

The World's Fairs in Paris

In the XIX century, France is at the forefront in representing culture, the European epicenter of artistic currents such as the romanticism, Darwinism or positivism, where the most outstanding artists and intellectuals of the period met. It was also a time of interest in Spanish culture, Goya was the representative of the Spanish tradition, along with the publications of travel books and examples of representations such as Carmen by Mérimée and Bizet, gave rise to a stereotyped image of Spanish culture and society in which French society fixed. The universal exhibitions arose as a way to find new forms of artistic expression and with the idea of showing the latest technological, industrial and scientific advances.

The idea of Spain in the XIX century, this was associated with the flamenco stereotype and bullfighting and was thus shown in several of the universal exhibitions held in Paris in 1855, where Fine Arts were included for the first time, groups of Spanish painters exhibited works on bullfighting (among other topics) such as Manuel Castellano with the work Bullfighters and fans before a bullfight bulls, Juan José Martínez Espinosa, author of Picadores rehearsing with their horses and Eugenio Lucas with the work Peleas de toros en Madrid. The Universal Exposition in Paris of 1867 was the one that caused one of the most important controversies when a stuffed bull's head was exhibited in the Spanish building along with the bullfighting tools, according to Ángel Fernández de los Ríos. At the Paris Exposition of 1878, the sculptor Ricardo Bellver presented a sculpture of the right-handed Lagartijo, The correspondent of La Iberia cited a painting by Agraeil depicting bulls and picadors in a corral before a bullfight and a work by Jules Worns that depicted a bullfighter conversing with a manola. The exclusion of Zuloaga's work Preparations for the bullfight, at the Universal Exhibition of 1900 caused a great scandal, as the painter was one of the most important representatives of the Spanish school of painting.

Bullfighting and economy

With bullfighting and economy, reference is made to the economic dimension that bullfighting has in the economy of the cultural industry and its consumption.

Among the structure that forms the bullfighting industry are direct professionals such as bullfighters: (bullfighters, banderilleros, picadors and subalterns), fighting bulls and fighting bull ranchers, bullring businessmen, public and institutions (autonomous communities, town halls, and councils and administration) among others. Many; to which are added veterinarians, manufacturers of material such as banderillas, rapiers, pikes; or tailors and everything necessary to start a bullfighting celebration of any of the different types: bullfights, running of the bulls, bullfights, corre bous, temptations in the countryside or celebrations held in the street such as the trimmers. In addition to the impact direct economic, bullfighting has a significant impact on the service sector such as tourism, hospitality, trade, distribution and feeding of bull meat, media, printing, etc.

The economic figures vary depending on the type of festivities held, thus the Pamplona Bull Fair in the middle of Sanfermín had an impact of seventy-four million euros in 2018. In Toledo the economic impact is eight million euros euros; season tickets for the San Isidro Fair generated around seventy-three million euros, while hotels and restaurants generated close to forty-seven million euros in 2019.

Legal status

Spain

In Spain, the protection of bullfighting as a cultural asset has been included in the legislation since 1991, mentioned by the Supreme Court in 1998, later Law 18/2013 that regulates bullfighting and Law 10/2015 was approved by which it is protected as Intangible Cultural Heritage, in accordance with the Historical Heritage Law of the State by which they have the obligation to guarantee the conservation of bullfighting as well as to promote it and facilitate access to it as part of the cultural knowledge of the Spanish.

On July 28, 2010, the Parliament of Catalonia approved with 68 votes in favor, 55 against and 9 abstentions to abolish bullfighting in Catalonia as of January 1, 2012. Later, on October 20 In 2016, the Spanish Constitutional Court declared the bullfighting ban in Catalonia unconstitutional.

In April 2016, the Parliament of the Balearic Islands approved a law to prohibit bullfighting from June of that year. In November 2017, the Council of Ministers approved appealing the law to the Constitutional Court, which declared the law unconstitutional in December 2018, overturning the ban.

In 2021 the mayoress of Gijón decided to prohibit bullfighting in the city after the controversy caused by the name of two of the bulls that participated in the Begoña fair that year, for which reason Asturias has been the only autonomous community in which no bullfighting shows of any kind are held.

France

In 2011, the French Ministère de la Culture declared bullfighting a national Intangible Cultural Heritage. bullfighting and bullfighting in the country.

In 2019, the Marseille Administrative Court of Appeal dismissed the appeal filed by anti-bullfighting groups seeking to prohibit minors under sixteen from attending bullfighting schools in Nimes, Arles and Béziers; as the Administrative Court of Nimes and Montpellier have already done, relying on French law. This measure was supported by the French Council of State.

Portuguese

In 1836 in Portugal, during the reign of María II of Portugal, the prohibition of the death of bulls in the ring was decreed, but allowed and encouraged its evolution in such a way that it adopted its own original style. It was customary for the royal guard to protect the public with halberds and the forks of the muquete or forcado. Once the function of protecting the walls of the trenches or protective barriers was used in the the guard became the one to hold the bull with the strength of his arms, a gesture known as pega until he guided it to the bullpen. The tradition has remained intact since the XVII. In September 2019 Portugal shielded bullfighting by declaring the law that prohibited bullfighting unconstitutional. bullfights.

Additional bibliography

- Printing and stereotyping of M. Rivadeneyra, ed. (1873). Rules for torear and art of all sorts: published in No. 45 of El Averiguador. Madrid. Consultation on 15 January 2020.

Contenido relacionado

1964

XVII century

Morelia inquisition