Bourbon restoration in Spain

The Bourbon Restoration is known as the political stage in the history of Spain developed under the monarchy that lasted from December 29, 1874 (the moment of the pronouncement of General Arsenio Martínez Campos that ended to the First Spanish Republic) and April 14, 1931 (date of the proclamation of the Second Republic). The name alludes to the recovery of the throne by a member of the House of Bourbon, Alfonso XII, after the parenthesis of the Democratic Six-Year Period.

The political regime of the Restoration, based on the Constitution of 1876, was characterized by institutional stability and the construction of a liberal model of the State, until its progressive decline after the crisis of 1917 and the dictatorship of Primo Rivera (1923-1930). It was based on the four pillars devised by its creator, the liberal-conservative politician Antonio Cánovas del Castillo: King, Cortes, Constitution and "turno" (peaceful alternation between "dynastic parties"). The "turnismo" facilitated bipartisanship with two large parties, the Conservative Party of Cánovas and the Liberal Party of Sagasta, which split after the death of their leaders. Thus, the system was oligarchic and centralist, and the Church gained economic, ideological (by controlling a large part of education) and social power (by declaring Spain constitutionally as a confessional State, although with tolerance towards non-Catholic cults in the sphere of private).

Cánovas promised (and fulfilled) that the ways and manners of the reign of Isabel II would be changed, overcoming the de facto single party system that had led to a lack of legitimacy of Isabel II and her subsequent overthrow in the Revolution of 1868. However, the political regime of the Restoration will be based on the systematic electoral fraud carried out by the Minister of the Interior with the typecast thanks to the cacique network extended throughout the territory. In fact, the changes of government ("the turn") took place before the elections and not after, as in parliamentary regimes (not fraudulent). The regenerationist Joaquín Costa characterized it in 1902 with the term "oligarchy and caciquismo". In the more than twenty general elections that took place between 1876 and 1923, no government lost them.

The reign of Alfonso XII (1874-1885)

The legitimacy of the new regime is established with the Constitution of 1876 that conformed the new State model with a legislative power divided into two chambers: the Congress of Deputies and the Senate, with a census suffrage to elect Congress and half of the Senate (the other half was appointed by the king), and where the monarch retains a good part of the functions of head of state and executive power.

Antonio Cánovas del Castillo was the architect of the process in which the so-called "dynastic parties", conservatives and liberals, headed by himself and by Práxedes Mateo Sagasta, respectively, will alternate in power peacefully through the curious system of, firstly, carrying out the transfer of power to the opposing party that proceeded to call elections that would legitimize their government, in an inversion of the natural order of said process. To achieve this alternation, methods such as pigeonholing or punching were used.

The first Restoration elections took place on January 20, 1876, with the liberal-conservatives of Cánovas obtaining the majority, with 333 seats, thanks to the electoral "maneuvers" of the Minister of the Interior Francisco Romero Robledo, despite which were still held under the universal (male) suffrage system established in the Spanish Constitution of 1869. The drafting of the new Constitution was carried out by a commission chaired by Manuel Alonso Martínez.

The rise to power of General Martínez Campos led to a call for elections on April 20, 1879, which gave the liberal-conservatives 293 seats. Cánovas returned to power in December as a result of the split in conservative ranks due to the law abolishing slavery in the Antilles. He focused his efforts on achieving a stable alternation with the constitutionalists of Sagasta, who founded the Liberal-Fusionist Party in May 1880, already identified with the new regime. He came to power on February 10, 1881, in a trial of the peaceful alternation of the parties. He dissolved the Cortes and called new elections, in which thanks to the electoral "maneuvers" of the Minister of the Interior Venancio González y Fernández, his formation obtained 297 seats.

Sagasta governed until October 13, 1883, when it gave way to a government of liberal "conciliation" led by José Posada Herrera, from the Dynastic Left, who had to resign due to the hostility of the Sagastinos themselves. Then King Alfonso XII again entrusted the government to Cánovas, who again dissolved the Cortes; In the elections of April 1884, his formation obtained 318 deputies, again thanks to the "maneuvers" of Robledo Romero. In these elections, in the words of deputy José Mª Celleruelo, the fraudulent spirit of the electoral system is reflected: «The Census Board has been falsified; this one has falsified the auditors; the mayor falsified the presidencies of the polling stations, and the polling stations, after these three very serious falsifications, falsified the result of the election».

Regarding the drafting of article 11 of the Constitution of 1876, which regulated the religious issue, a harsh conflict arose with the Catholic Church since it did not recognize Catholic unity and this despite the fact that it established the confessional of the state. Article 11 said:

The Catholic, Apostolic, Roman religion is that of the State. The Nation is obliged to maintain the cult and its ministers. No one will be disturbed in Spanish by his religious opinions, or by the exercise of his respective cult, except for respect for Christian morals. However, other ceremonies or public demonstrations will not be permitted than those of the State religion.

The conservative governments proposed a restrictive interpretation that provoked protests from foreign ambassadors. The debate intensified in relation to teaching, with the bishops demanding the guarantee of doctrinal teaching, as a "right" recognized in the concordat of 1851, of the supervision and censorship of the contents of teaching, to the detriment of the inspection function. that corresponded to the State itself.

The conflict in the regulation of the planned civil marriage spread, but without further development due to the opposition of the Church. It was not until November 1886, when the minister Alonso Martínez took the initiative to authorize marriage for non-Catholics. After intense negotiations, an agreement was reached with the Holy See, whereby the latter recognized the State's power to regulate the civil effects of marriage.

The Regency of María Cristina (1885-1902)

The death of Alfonso XII gave way to the regency of María Cristina, a period that began with the government of Sagasta characterized by the approval of the Law of Associations, freedom of the press, the extension of universal suffrage to men (1890) and the creation of the institution of the jury, among other advances. The appearance of anarchism and socialism began in this period through the PSOE (founded in 1879) with the first labor movements that emerged from the industrial revolution.

Economic development

Emigration to America, weak population growth (Spain only had 18.5 million inhabitants in 1900) and situations of famine and epidemics, produced a growing inequality between Spain and the rest of the European countries.

Spain employed 79% of the population in low-yield agriculture and in the manufacture of agricultural products. The protectionist system prevented the modernization of the sector, unable to compete. Latifundismo conditioned the life of peasants in large areas of the peninsula, especially in Andalusia and Extremadura. Only some sectors (wine, oil, fruit) are beginning to take off with still insignificant exports to other European countries.

The development of industry and communications is scarce. While Europe is experiencing the industrial revolution in full swing, only Catalonia (with the introduction of the railway and the textile industry), areas of the Basque Country (steel industry in Bilbao), and mining operations in Andalusia (iron, copper and lead) and Asturias (coal) advance on the path of progress. This will accentuate regional inequality.

In 1888 the Universal Exhibition of Barcelona was held.

A changing society

The Restoration entailed a profound administrative and legal centralization. Catalan and Basque nationalism were quick to react. The first linked to his own bourgeois revolution and cultural identity; the second, who had lost the Fueros after the Carlist wars, sought to define his future. The Basque Nationalist Party, the League of Catalonia and the Catalan Union appear.

The labor movement was grouped around the PSOE, which advocated peaceful struggle and electoral participation, the UGT (founded in 1888) and anarchism in the Federation of Workers of the Spanish Region.

The monarchy will question these movements with a strong repression, with special virulence against anarchism. The territory of many of these clashes will be Catalonia.

Society was thus divided. On the one hand, the tradition represented by the parties of Cánovas and Sagasta: monarchists, defenders of a content model of openness and oblivious to the feelings of the new social classes. On the other hand, some movements of different signs, republicans and nationalists, representatives of the new bourgeoisie that still has not found its national space. Thirdly, the proletariat that will be grouped around a political party, the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party and two class unions, the General Union of Workers and the National Confederation of Labor. Everything, under the watchful eye of the Church.

Governments until 1898

The premature death of Alfonso XII of Spain on November 24, 1885 decided Cánovas to grant power to the Liberal Party, in an agreement for the consolidation of the regime that would go down in history as the Pact of El Pardo, but that it would precipitate the defection of the canovism of a group led by Romero Robledo. The new government of Sagasta, and first of the Regency, was appointed on November 25, 1885, calling elections for April 4 of the following year. The usual irregularities were repeated, with the Liberals obtaining 278 certificates, among them, for the first time, Álvaro de Figueroa, Count of Romanones, obtained his for Guadalajara.

On June 26, 1890, the liberal government changed the Electoral Law, restoring suffrage to men over 25 years of age. This system did not suppose a substantial variation of the electoral vices, but brought with it new political behaviors that, in the long run, would lead to its crisis and dismantling.

The liberal Cortes dissolved in December 1890, seizing power from the Cánovas government, which called elections for February 1891. Although the methods used by its Minister of the Interior, Francisco Silvela, were somewhat less scandalous than those of his predecessor Romero Robledo, the Conservative Party obtained the majority, although somewhat less comfortable than usual, with 253 seats. Supporters of the republic scored some small successes with 31 seats.

The unit of the conservatives was staggering, it had already suffered a dissidence with Romero Robledo, although it had returned to the fold. This time it was Francisco Silvela, under the banner of moralization. His defection led to the resignation of Cánovas in December 1892, and made way for the third liberal shift.

The Sagasta government was formed, which called elections on March 5, 1893, which granted the well-known and usual majority to the Liberals with 281 posts. The surprise was given by the Republicans with 47 seats, the second group surpassing even the official conservatives affected by internal dissent.

The conflict in Morocco and the last act of the overseas colonial crisis led Sagasta to cede power to Cánovas in March 1895. The conservative leader governed for a year with the support of the liberal majority, until the elections on 12 February. April 1896, which were held with the abstention of the Progressive Republican Party, divided after the death of Ruiz Zorrilla, the transition of many Republicans to the liberal ranks, and the position of the federalists of Pi y Margall in support of autonomy or independence from Cuba. As a novelty, socialist candidacies were presented for the first time, although they did not obtain any minutes. As was foreseeable, the majority went to the conservatives, although the magnitude of the victories of the parties in turn were decreasing.

The assassination of Cánovas, together with the most critical moment of the war in Cuba, in addition to the internal disputes in the conservative ranks, precipitated the return to power of Práxedes Mateo Sagasta. After the usual dissolution of the Chambers, the new elections provided a comfortable majority for the Liberals, with 284 seats, against a Conservative Party that continued to split after the disappearance of its undisputed leader, in the pro-government Conservative Union of Silvela, and the dissidents from Robledas., in full decline. The Republican Union renounced abstentionism, although its internal dissensions led to a poor result.

Culture opens up to the world

Industrial development, institutional stability and improved trade with other European countries gave rise to small but significant changes in Spanish culture.

The Catholic Church, supported by classical and dynastic politics, continued to play a fundamental role in the popular culture of the late 19th century when 65% of the Spanish population is illiterate. However, the Spanish labor movement began to show its energy with the opening of libertarian universities and popular schools, highly ideologized but which allowed many men and women from rural areas to access a minimum of knowledge.

In the arts, education and literature there is an openness to ideas that come from beyond the Pyrenees. The growth of large cities, the result of industrialization, gives way to a modern urbanism that has its most prominent expression in the Catalan modernist movement, led by Antonio Gaudí. The Republicans, convinced of the importance of education in the future of Spain, unite around the Institución Libre de Enseñanza project, with Francisco Giner de los Ríos and Emilio Castelar among their main leaders, seeking the formation of a ruling class modern and european In literature, romanticism gave way to realism, with Benito Pérez Galdós, Emilia Pardo Bazán and Leopoldo Alas Clarín as the greatest exponents.

America and Europe: two perspectives

In Europe two currents of development take place that will affect all subsequent history: on the one hand, Great Britain, France, Belgium, the Nordic countries and the German Confederation continue the industrialization process unstoppable; on the other hand, southern and eastern Europe maintains traditional agricultural structures. In the former, liberalism and the industrial bourgeoisie set the guidelines for development; in the latter, the traditional model of political organization is still present.

Spain is at a crossroads in which it will not finish defining itself. In Catalonia and the Basque Country, the timid presence of the industrial revolution can be appreciated. The rest of Spain follows an agricultural economy. In addition, the power structures continue to be based on the dynastic parties, and not on the new emerging classes.

In America, the United States emerges as a great power, a country to which Spain will not pay special attention until it is too late. The former Spanish colonies have achieved their independence and are beginning to depend more on the United States and Great Britain for their economic relations than on the former metropolis.

Margallo's War (1893-1894)

In 1893 the Muslims in Melilla opposed the construction of the Purísima Concepción Fort in Sidi Guariach, and organized an attack on October 3, 1893. The 1,463 soldiers of the Melilla garrison had to face between 8,000 and 10,000 Muslims. Minister José López Domínguez sent a total of 350 soldiers as reinforcements, under the command of General Ortega. In the counterattack on October 28, Governor Juan García Margallo died at the gate of the Cabrerizas Altas fort. A fleet was sent which supported the Spanish troops with naval bombardments. Subsequently, an expeditionary army was created on the peninsula, under the command of Captain General Arsenio Martínez Campos, of 20,000 men. These troops arrived in Melilla on November 29, producing a deterrent effect, and the fighting ceased. After this, Spain completed the construction of the fort. On March 5, 1894, General Arsenio Martínez Campos signed the Treaty of Fez with the Sultan, in which he promised to guarantee peace in the region and compensated Spain with 20 million pesetas.

The Cuban War (1895-1898)

Spanish policy towards Cuba after the signing of the Peace of Zanjón in 1878, which put an end to the Ten Years' War, was its assimilation to the metropolis, as if it were a province more Spanish—it was granted, like Puerto Rico, the right to elect deputies to Congress in Madrid. This policy of Spanishization that sought to counteract Cuban secessionist nationalism was reinforced by the facilities granted for the emigration of peninsulars to the island and that was especially taken advantage of by Galicians and Asturians —between 1868 and 1894 they arrived close to half a million people, for a total population of 1.5 million in 1868. But the Restoration governments never approved the granting of any type of political autonomy for the island, as they considered that this would be the step prior to independence. A former Liberal Overseas minister expressed it this way: "by many paths you can go to separation, but the teachings of history tell me that you go by rail on the path of autonomy." Cuba was considered "part of the territory of the nation, which politicians had to preserve in its integrity".

In this way, they refused to accept what the Cuban Liberal Autonomist Party was proposing, which, in the face of the Spanish Constitutional Union, absolutely opposed to any concession, wanted to “obtain by peaceful and legal means political institutions for the island, in which they could participate”. What they did achieve was the definitive abolition of slavery in 1886. Meanwhile, Cuban nationalism for independence continued to grow, fueled by the memory of the heroes of the war and the Spanish brutalities in it.

On the last Sunday of February 1895, the day the carnival began, a new independence insurrection broke out in Cuba planned and directed by the Cuban Revolutionary Party, founded by José Martí in New York in 1892, which would die in the month of following May in a confrontation with Spanish troops. The Spanish government reacted by sending an important military contingent to the island —some 220,000 soldiers would arrive in Cuba in three years. the insurrection— determined to bring the war "to the last man and the last peseta". "With the new Captain General, the Spanish strategy changed radically. Weyler decided that it was necessary to cut off the support that the independentistas received from Cuban society; and for this he ordered that the rural population be concentrated in towns controlled by the Spanish forces; at the same time he ordered the destruction of crops and livestock that could serve as supplies to the enemy. These measures gave good results from a military point of view, but at a very high human cost. The reconcentrated population, without sanitary conditions or adequate food, began to fall victim to diseases and die in large numbers. On the other hand, many peasants, with nothing to lose anymore, joined the insurgent army». The brutal measures applied by Weyler caused a great impact on international public opinion, especially in the United States.

Meanwhile, in 1896 another independence insurrection began in the Philippine archipelago led by the Katipunan, a Filipino nationalist organization founded in 1892. Unlike Cuba, the rebellion was stopped in 1897 although General Polavieja resorted to some methods similar to those of Weyler—José Rizal, the leading Filipino nationalist intellectual, was executed. In mid-1897 General Polavieja was relieved of command by General Fernando Primo de Rivera who reached a pact with the rebels at the end of year.

On August 8, 1897, Cánovas was assassinated, and Sagasta, the leader of the Liberal Party, had to take over the government in October, after a brief cabinet presided over by General Marcelo Azcárraga Palmero. One of the first decisions he made was to remove General Weyler, whose tough policy was not giving results, being replaced by General Ramón Blanco y Erenas. Likewise, in a last attempt to reduce support for the insurrection, political autonomy was granted to Cuba —also to Puerto Rico, which remained at peace—, but it arrived too late and the war continued. On the other hand, Spanish policy in Cuba was concentrated in satisfying the demands of the United States, with the aim of avoiding war at all costs since the Spanish rulers were aware of Spain's naval and military inferiority, although the press, instead, deployed an anti-American and exaltation campaign Spanish.

The disaster of 98

In addition to geopolitical and strategic reasons, US interest in Cuba —and in Puerto Rico— was due to the growing interdependence of their respective economies —investments of US capital; 80% of Cuban sugar exports already went to the United States—and also to the sympathy that the Cuban independence cause aroused among public opinion, especially after the tabloid press aired the brutal repression exercised by Weyler and launched an anti-Spanish campaign calling for the intervention of the US army on the side of the insurgents. In fact, the US aid in arms and supplies channeled through the Cuban Junta chaired by Tomás Estrada Palma and the Cuban League "was decisive in preventing the subjugation of the Cuban guerrillas", according to Suárez Cortina. The US position was radicalized with the republican president William McKinley, elected in November 1896, who discarded the autonomist solution accepted by his predecessor, the democrat Grover Cleveland, and clearly bet on the independence of Cuba or the annexation —the US ambassador in Madrid made an offer to buy the island that was rejected by the Spanish government. Thus, the granting of autonomy to Cuba approved by the Sagasta government —the first experience of this type in contemporary Spanish history— did not satisfy at all the North American claims, nor those of the Cuban independence fighters who continued the war. Relations between the US and Spain worsened when the US press published a private letter from the Spanish ambassador Enrique Dupuy de Lome to the minister José Canalejas, intercepted by Cuban espionage, in which he called President McKinley "weak and popular, and also a politician who wants... to look good with the jingoes of his party".

In February 1898, the American battleship Maine sank in the port of Havana where it was anchored as a result of an explosion —264 sailors and two officers died— and two months later, on April 19, the Congress of The United States passed a resolution calling for Cuban independence and authorizing President McKinley to declare war on Spain, which he did on April 25. The congressional resolution stated "that the people of the island of Cuba is, and has the right to be, free, and that the United States has the duty to request, and therefore the United States government requests, that the Spanish government immediately renounce its authority and government over the island of Cuba and withdraw from Cuba and Cuban waters its land and naval forces". thesis put forward by the Spanish commission that the explosion was due to internal causes. The official American report attributed it, on the contrary, to external causes, and it was, in the words of McKinley's Message to Congress, "patent and manifest proof of an intolerable state of affairs in Cuba."

The Spanish-American War was brief and was decided at sea. On May 1, 1898, the Spanish fleet from the Philippines was sunk off the coast of Cavite by a North American fleet —and the landed North American troops occupied Manila three and a half months later— and on July 3 the same thing happened to the fleet sent to Cuba under the command of Admiral Cervera off the coast of Santiago de Cuba —a few days later Santiago de Cuba, the second most important city on the island, fell into the hands of the American troops that had landed. Soon after, the Americans occupied the neighboring island of Puerto Rico. The Spanish only managed to sink one American ship in the entire war: the USS Merrimac. There were Spanish officers in Cuba who expressed "the conviction that the government of Madrid had the deliberate intention that the squadron be destroyed as soon as possible, to quickly reach peace."

As if that were not enough, some of the best units of the navy such as the battleship Pelayo or the cruiser Carlos V did not intervene in the war despite being superior to their American counterparts,[citation required ] increased the feeling among some that they were witnessing a "controlled demolition" by the Spanish government of ungovernable colonies that were going to be lost sooner rather than later to prevent the restoration regime collapse[citation needed] (in fact, the few possessions that Spain retained after this war were sold in 1899 to Germany). Finally, the Spanish government asked in July to negotiate peace.

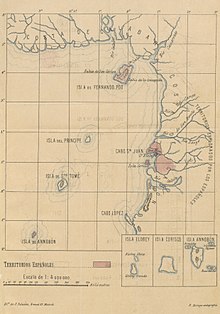

After learning of the sinking of the two fleets, the Government of Sagasta requested the mediation of France to start peace negotiations with the United States that, after the signing of the Washington protocol on August 12, began on October 1, 1898 and which culminated in the signing of the Treaty of Paris, on December 10. Through this Treaty, Spain recognized the independence of Cuba and ceded to the United States, Puerto Rico, the Philippines and the island of Guam, in the Marianas archipelago. The following year Spain sold to Germany for 25 million dollars the last remnants of its colonial empire in the Pacific, the Caroline and Mariana Islands —except Guam— and Palau. «Classified as absurd and useless by a large part of historiography, the war against the United States was sustained by an internal logic, in the idea that it was not possible to maintain the monarchical regime if it was not from a more than foreseeable military defeat», affirms Suárez Cortina. A point of view that is shared by Carlos Dardé: «Once the war was raised, the Spanish government believed that it had no other solution than to fight, and lose. They thought that defeat—certain—was preferable to revolution—also certain—». Granting “independence to Cuba, without being defeated militarily… would have implied in Spain, more than likely, a military coup d'état with broad popular support, and the fall of the monarchy; that is, the revolution." As the head of the Spanish delegation at the peace negotiations in Paris, the liberal Eugenio Montero Ríos, said: "Everything has been lost, except the Monarchy." Or as the US ambassador in Madrid put it: the politicians of the dynastic parties preferred "the chances of a war, with the certainty of losing Cuba, to the dethronement of the monarchy".

Regenerationism

After the loss of the colonies, in Spain there were movements that tried to overcome a crisis that was also one of identity. What has been called «regenerationism» arises, that is, a process through which to overcome the ways and policies of the past to find a new path in all orders.

After the government of Sagasta and its leading role in the Disaster, a change of government was imposed, entrusted to the conservatives, chaired by Francisco Silvela. After the pertinent dissolution of the Cortes, elections were called on April 16, 1899, with a tenuous intervention by the Ministry of the Interior, run by Dato. For this reason, the government majority of 222 seats, although comfortable, was not as spectacular as usual, while the Liberals, with 93 votes in the official sector, reaped the best result for the party that did not have the turn of government. In this cabinet, the problems of the Public Treasury, run by Raimundo Fernández Villaverde characterized the turn of the century, and put an end to the government in October 1900. After a bridging government of General Azcárraga, Sagasta agreed, for the last time, to the presidency of the executive In the usual way, he dissolved the Cortes, and called elections for May 1901; obtaining a very strong atomization of the Chamber, although the liberals achieved a comfortable result with 233 minutes. The Republicans began a slow recovery, with attempts at renewal marked by the alliance of Alejandro Lerroux with the historical leaders of Nicolás Salmerón.

The constitutional period of the reign of Alfonso XIII (1902-1923)

In 1902 Alfonso XIII acceded to the throne, with Antonio Maura as head of the Government trying to promote a policy of openness that would avoid the feared workers' revolution: elimination or attenuation of electoral caciquismo and administrative decentralization. But the army, hurt by the defeat and the strong criticism from public opinion after the war, confronts the system and maintains constant threats towards the modernization process.

The government keeps the army busy in Africa, in Morocco, where Spain shares colonization with France, even establishing the Spanish Protectorate of Morocco in 1912; and it is that, since 1908, the confrontations with certain tribal sectors of the Moroccan population had been intensifying. The Tragic Week in Barcelona (summer 1909) will be the popular response to the unfair system of recruiting troops established and will determine that Maura loses power, being replaced by the liberal government of José Canalejas. But he was barely able to adopt some decentralization measures, until his assassination in 1912 at the hands of an anarchist. The governments of the Count of Romanones and Eduardo Dato followed one another.

As a result of the economic and social impact of the First World War, despite the fact that Spain remained neutral, the crisis of the turno system began, which ended with the adoption of an authoritarian solution to it: the dictatorship of Primo from Rivera.

The failure of the reform of the system "from above" (1902-1914)

The defeat against the United States and the loss of the last remnants of the colonial empire by the Treaty of Paris, opened the way for a critique, more global than systematic, of the national reality. At this moment, reformist attitudes incubated before the disaster arise. A desire for change that the political regime did not escape, seriously eroded by its exclusive nature, and by its inability to integrate the new emerging forces, in line with the process of modernization of the Spanish reality.

Reforms controlled by the system (Maura, Canalejas) were attempted, but failed because they had not frankly accepted the regenerationist approaches, and did not assume the new democratic attitude that the irruption of the masses in public life imposed. To this political impotence was added the internal crisis of the system due to the fragmentation of the parties of the day, after the loss of the historical leaders, Cánovas and Sagasta, respectively in 1897 and 1903.

After Silvela's withdrawal, the conservatives found an indisputable leader in Maura, but after the Tragic Week of July 1909, the foundations were laid for a split between Dato's supporters, the Mauristas, as well as other factions more authoritarian and opportunistic groups that were grouped in "ciervism". For their part, the liberals seemed to find a leader in Canalejas, but his premature death in 1912 would fragment the party between the orthodox liberals of Romanones and the liberal-democrats of García Prieto.

The beginning of the reign of Alfonso XIII, which took place on May 17, 1902, was marked by the rise of regionalist, workerist and republican political forces, as well as a resurgence of anticlericalism, and the aggressive explicitation of militarism, hitherto latent. Sagasta, the old liberal leader, left power on December 6, 1902, only to die less than a month later. He was replaced by a conservative government led by Francisco Silvela, assisted by Antonio Maura in the Ministry of the Interior. After five months of preparations, in which Maura began a campaign to dismantle the caciquil networks, which turned out to be incomplete, the elections were held on March 8. The result was the usual majority for the party in power and the loyal opposition, with 230 seats for the Conservatives, and 93 for the official Liberals. Although there was a great advance of Republicans (36 deputies) along with regionalists and Carlists, with 7 seats each. These results filled Alfonso XIII with anger, who reproached Maura for his "electoral honesty", although he publicly expressed his satisfaction.

In the following years, the leadership of the two great parties that followed the turn was clarified. With Silvela removed from the government presidency, the dispute over his succession between Fernández Villaverde (fleeting president until November) and Antonio Maura, was resolved in favor of the latter, who led a conservative government until an incident with the young King, who forced his resignation in December 1904. It was the turn of the Liberals, who after another two brief interims by Azcárraga and Fernández Villaverde, acceded to the government on June 23, 1905. The executive was presided over by Montero Ríos, a surviving politician from the Democratic Six-year period, and actually nominal head of a dissidence, the radical Democratic Party, inspired by José Canalejas, against the traditional liberalism embodied by Segismundo Moret. However, the liberals presented themselves united in the elections of September 1905, obtaining a victory without complications, with 229 deputies, before the withdrawal of the electorate and the stagnation of the republicans and regionalists.

Several fleeting liberal governments followed one another (Montero Ríos, Moret, López Domínguez, Vega de Armijo), which shows a lack of leadership, which finally led to ceding power to Maura, then undisputed conservative leader, and willing, in In principle, to continue the regenerationist policy already begun in 1904. However, the elections of April 21, 1907 were scandalously controlled by the Minister of the Interior Juan de la Cierva, even surpassing the methods of Romero Robledo. The Conservatives won an overwhelming victory with 252 deputies, and this led to a retreat by the Liberals in protest of De la Cierva's methods.

Antonio Maura, during the so-called «long government», with renovating attempts, set out to carry out his revolution from above, focused on the culmination of reformist projects such as the Catalan autonomist lawsuit and the attempt to dislodge caciquismo through the reforms of municipal and electoral laws. In this last section, it was proposed to carry out a reform introducing the proportional system, or to eliminate single-member constituencies, prone to caciquismo; However, the new electoral law approved, although it introduced novelties such as compulsory voting or the introduction of some methods to ensure the purity of the process, such as the constitution of the Census Boards, essentially did not correct the dysfunctions of the electoral system, and even aggravated them with the sadly famous article 29, with which candidates who presented themselves alone were automatically elected, without the need for a vote. That meant legal recognition of the inveterate custom of the single candidate, generally close to the government, and common, above all, in rural areas.

In addition to the union of liberals and republicans in the opposition, through a left-wing bloc, the growing involvement in Morocco degenerated into an open colonial war in the summer of 1909 (the Melilla war), and was the cause of the outbreak of popular violence in Barcelona's Tragic Week at the end of July, due to the mobilization of reservists. The subsequent repression, including the execution of Francisco Ferrer Guardia, founder of an anarchist school, aroused not only condemnation by foreign public opinion, but also harassment by the opposition until Maura's resignation was achieved.

The head of the anti-Maurista front was led by Segismundo Moret, who obtained power on October 22, although the King, in an unprecedented action, denied him the Decree of Dissolution of the Cortes, for which the government was in a situation provisional, until José Canalejas, true restorer of the unity of the liberal party, agreed to the presidency of the Council of Ministers in February 1910. Now he obtained the dissolution, and elections were called in May, with a peculiar situation of confrontation between the two dynastic parties, for the first time in the entire Restoration. The two parties also appeared united and seamless, with two strong leaders, Antonio Maura and José Canalejas. However, due to the application of the aforementioned article 29, 30% of the population was deprived of the vote, which benefited the party in government, in this case the liberal party. The party in government obtained 219 deputies, the lowest number of all those held, and the conservative opposition, 102, the best result for the opposition, not so far, but even never surpassed since. In addition, the Republicans, with 37 seats, obtained a magnificent result, presenting themselves on this occasion in coalition with the Socialists who obtained, for the first time, a seat held by Pablo Iglesias.

During the government of Canalejas, to prevent the growth of clericalism, the padlock law was promulgated, which prohibited the establishment of new religious orders in Spain. An attempt was also made to alleviate the dysfunctions of the parliamentary system through measures to rectify the electoral system, carrying out a bill that sought to reduce the weight of rural districts. Unfortunately, these reforms were never carried out, and the contradictions between the political-electoral system and the socioeconomic reality became increasingly worse.

The Canalejas government also acted decisively on the Moroccan problem, initiating negotiations with France to delimit the respective areas of influence. However, in 1912, the renovation works started by Canalejas were cut short, due to the attack that ended his life on November 12, 1912.

The crisis of the shift system (1914-1922)

After some transitional governments of Manuel García Prieto and the Count of Romanones, the government was entrusted to the conservative Eduardo Dato, who called elections in March 1914. Article 29 was still in force, so the government won again, although with a meager majority of 188 seats, which, for the first time, was not so comfortable to govern, although the opposition was quite fragmented. For this reason, the datista cabinet sought the support of other conservative minorities to maintain itself, in an unstable manner, until December 1915. After the failure, a liberal government headed by Romanones was formed, which called elections for March 1916, which this time yielded a clear liberal majority, although 35% of the deputies were elected without a vote. The system is in frank decomposition, the Government is awarded the majorities, and distributes the gaps among the minorities. The levels of nepotism are also scandalous, 54 deputies are relatives of great political figures, among them Romanones had his son and his son-in-law. It is not strange that the difference between the real Spain and the official Spain was more and more evident and unfathomable.

The Spanish government decides to remain neutral in the First World War, but misses the opportunity it is offered to place itself in a privileged position within a war economy. The dynastic parties do not quite connect with civil society and the PSOE, the Republicans, the Catalan nationalists and the Basque nationalists with the PNV, better represent popular aspirations. The year 1917 is the year of revolts: the army unites around the Defense Boards in their internal confrontations; Republicans and Socialists join forces to offer an alternative to the political system (Assembly of Parliamentarians), as do Catalan and Basque nationalists, and constitutional guarantees are suspended; the revolutionary general strike of August 1917 caused serious clashes between unions and law enforcement.

With the liberals' possibilities exhausted, Eduardo Dato resumed the Presidency, with a climate of growing conflict, due to the interference of the army, the Catalan regionalist demands and the contradictory socioeconomic repercussions of the Great War; In addition, the revolutionary general strike of the summer of 1917 was added to this, in a process known by historiography as the crisis of 1917; which led to the resignation of the datista Cabinet. The crisis was averted by means of a government with a broad concentration of dynastic parties, including, for the first time, the Catalanists. The government was chaired by García Prieto, and called elections in February 1918, characterized by a strange electoral sincerity, which resulted in an uncertain result. The Liberals were the winners, with 167 seats, although the dissensions between them meant that the majority minority were the official Conservatives. The historic republicans continued their decline, although this was offset by the rise of the socialists and reformist republicans.

This sincerity contributed to aggravate the crisis of the system, forming a National Government, chaired by Maura, and with the presence of all the parliamentary heads of the parties related to the monarchy; but this effort lasted seven months, due to the differences between these chiefs. In June 1919, the new conservative government of Maura had to call new elections, with a suspension of constitutional guarantees. The left-wing minorities declared the new Cortes factional. The differences within the conservative ranks led to the new Cortes being more ungovernable, since the winning conservatives were divided into two factions of similar size. For this reason, after several governments, elections were again called by Dato, in December 1920, where the government recovered its unorthodox traditions, beset by problems, and trying to find a solid majority, which it achieved, with 232 conservative seats., 185 of which aligned with government datatists.

Successive governments have failed to calm things down. The Russian Revolution influences the unions, especially the CNT, which until 1921 will maintain revolts throughout Spain, from Andalusia to Catalonia (Bolshevik Triennium). That year Eduardo Dato is assassinated in another anarchist attack and until 1923 there were thirteen different governments in six years. The Annual Disaster in Morocco will end up leading the García Prieto government in 1922 to a last attempt at regenerationism.

The last constitutional government of the Monarchy (1922-1923)

The liberal government of Manuel García Prieto, constituted on December 7, 1922, with the support of the reformists of Melquíades Álvarez, one of whose members, José Manuel Pedregal occupies the Treasury portfolio, has in its program the reform of the Constitution, including article 11 that establishes the confessional nature of the State (although without proclaiming the separation of Church and State), thus trying to solve "the clerical religious problem" (as a commentator of the time called it).

However, when he called the elections in April 1923 (which would be the last of the Restoration) he again resorted to the old system of "oligarchy and caciquismo" denounced twenty years before by Joaquín Costa, among others, to endow himself with a similar majority in the Cortes that approves the reforms. In the newspaper La Voz, in the issue of March 6 of that year, curious statistics were presented on the family ties of the candidates: 59 children, 14 sons-in-law, 16 nephews and 24 with other relatives related to the founders of political dynasties, 52 of them for the conservatives and 61 for the liberals; and this without counting the interns and protégés. In addition, the candidates elected without a vote, thanks to article 29, broke the record with 146 seats. The Liberals, in coalition with the Reformists, won 223 seats, while the Conservatives won 108, of which 81 went to Sánchez Guerra's official supporters, 16 to the Cervistas and 11 to the Mauristas. The criticisms of the ABC newspaper to these last elections are a clear exponent of the fatigue that public opinion had reached due to the repeated manipulations of the popular will:

The elections have been agreed; almost all opposition, official and protected or consensual candidates. The year-by-year calls are repeated, or at two years the most distant, and yet any Government, as it is called or as it is painted, always has the majority, as great as it pleases, and even without breaking the tradition of the conventions. Electoral fiction has no pretensions of finesse.

Despite having a comfortable majority in the Cortes, García Prieto's renewal projects were hampered by the Crown itself, by the Army and by the Catholic Church. For example, the protest of a cardinal and the nuncio was enough for the proposal to change article 11 to be withdrawn. Finally, the establishment of the Primo de Rivera dictatorship on September 13, 1923, with the approval of King Alfonso XIII, put an end to any new reform initiative.

The dictatorship of Primo de Rivera (1923-1930)

With the support of the army, the bourgeoisie and King Alfonso XIII of Bourbon, the dictatorship of Primo de Rivera was only challenged by the labor unions and the republicans, whose protests were immediately silenced with censorship and repression. A Military Directorate was created with nine generals and an admiral, whose purpose, in his own words, was to "put Spain in order" to later return it to civilian hands. The Constitution was suspended, city councils were dissolved, political parties were banned, and the somatén was reestablished as an urban militia.

Democratic systems are also faltering in Europe. Fascism was implanted in Italy in 1925, the Nazi Party was founded in Germany, Russia was subjected to Stalin's dictatorship and totalitarian regimes reached Portugal and Poland.

Aware of the importance of keeping the army satisfied, the military campaign in Morocco gave it victory in the Rif War with the landing of Al Hoceima and the surrender of Abd el-Krim in 1926. Collaboration also contributed greatly between the Spanish and French armies. The unionism of the CNT and the recently created Communist Party of Spain was repressed and the dictatorship tolerated the UGT and the PSOE, organizations that contributed some collaborators in labor matters such as Francisco Largo Caballero, state councilor, with which the regime tried to obtain legitimacy before the labor leaders. The Catalan bourgeoisie also began to support him. Social legislation limited the work of women, built workers' housing and instituted a model of professional training. He also initiated a policy of extensive public investment to improve communications (roads and rail), irrigation, and hydraulic power.

These early successes brought him great popularity. He created the Patriotic Union organization as a uniter of all political aspirations, as well as the National Corporate Organization as a vertical union modeled on Fascist Italy, substituting in 1925 the Military Directorate for a civilian one.

However, the early supporters turned against him. The Catalan bourgeoisie saw its attempts to decentralize frustrated, with an even more centralist policy that, in economic matters, came to favor oligopolies. The working conditions continued to be appalling and the repression of the workers distanced the UGT and the PSOE from the dictator's project. The economy proved incapable of assuming the world crisis of 1929. In January 1930, Primo de Rivera resigned.

The “soft dictator” (1930-1931)

The monarchy, an accomplice of the dictatorship, will be the object in question from the union of all the opposition in August 1930 in the so-called Pact of San Sebastián. The governments of Dámaso Berenguer, called the soft dictator, and of Juan Bautista Aznar-Cabañas will do nothing but lengthen the decadence. After the municipal elections of 1931, on April 14 the Second Republic was proclaimed, thus ending the Bourbon Restoration.

Education in the Restoration

At the beginning of the xx century, Spain possessed some of the best intellectuals in Europe and, also, the lowest rate high illiteracy. New organisms were created from the ILE. The facts that best reflect this way of thinking were:

- 1882: The Museum of Primary Institution was created, later called the National Pedagogical Museum. Besides being a museum, it was a teacher training center with an area of lectures and courses.

- 1898: it was reformed from the Normal School because of the need for deeper training. One of the greatest changes was the implementation of the same curriculum for teachers. New subjects such as Pedagogy were included.

- 1900: creation of the Ministry of Public Education and Fine Arts

- 1901: enlargement of compulsory schooling up to the age of 12, a measure adopted by a conservative government.

- 1902: incorporating the payment of teachers to the State Administration, thus eliminating the old problem that the Moyano Act (1857) had created by transferring that obligation to the municipalities.

- 1907: the Board of Enlargement of Scientific Studies and Research (JAE) was established as a commitment of the liberals to improve education in Spain. The head of the JAE was José Castillejo. This Board created a number of centers, institutes and laboratories, including the Student Residence in 1910 and the Institute-School in 1918.

- 1909: The Higher School of Magisterium was established in 1911 as the School of Higher Studies of Magisterium, as a centre for continuing the training of teachers who wish to hold positions of greater responsibility as the director.

- 1911: the General Directorate of First Education was created, which was entrusted by the liberal government to Rafael Altamira, a regenerator linked to the ILE. This was born for the rationalization and modernization of primary school, education sector in the cultural and social programs of the regeneration of the time.

A committed culture

The generation of 98, a term popularized by Azorín, represents better than any other movement the break between the intellectual elite and the political system. Disappointed with the monarchy, they soon defended a new model, from the letters with men like Joaquín Costa, Miguel de Unamuno (who will have to go into exile in Fuerteventura) or Vicente Blasco Ibáñez whose pen will be implacable against Alfonso XIII. From philosophy, the most faithful representative will be José Ortega y Gasset.

The magazine España, founded by Ortega and also directed by Araquistain and Azaña, is closed, Ramón María del Valle-Inclán is sanctioned and the universities suffer constant closures.

Picasso develops a brilliant work in Paris, giving cubism full meaning and creating one of his masterpieces: Les Demoiselles d'Avignon.

Contenido relacionado

483

472

471