Biome

A biome (from the Greek «bios», life), also called a bioclimatic landscape or biotic area is a certain part of the planet that share the climate, flora and fauna. A biome is the set of ecosystems characteristic of a biogeographic zone that is defined from its vegetation and the animal species that predominate. It is the expression of the ecological conditions of the place at the regional or continental level: the climate and the soil determine the ecological conditions to which the communities of plants and animals of the biome in question respond.

Depending on latitude, temperature, rainfall and altitude, in short, and on the basic characteristics of the climate, the earth can be divided into zones with similar characteristics; In each of these zones a vegetation (phytocoenosis) and a fauna (zoocenosis) develop which, when related, define a biome, which includes the notions of community and the interaction between soil, plants and animals.

There are different systems for classifying biomes, which in general tend to divide the earth into two large groups —terrestrial biomes and aquatic biomes—, with a not too large number of biomes. On a planetary scale, the jungle, the savannah, the steppe, the forest and the tundra are the large biomes that characterize the biosphere and that have a zonal distribution, that is, they do not exceed certain latitudinal values. On a regional or continental scale, biomes are difficult to define, partly because there are different patterns and also because their boundaries are often diffuse (see the concept of ecotone).

Biomes are often known by their local names. For example, a grassland biome is known as prairie in North America, savannah in Africa, steppe in Asia, pampas in South America, and veld in South Africa.

Terrestrial biomes are described by the science of biogeography. By extension, one speaks of the microbiome to designate the sphere of microbial life.

The concept of biome should not be confused with other similar concepts such as ecozone habitat or ecosystem. The different ecoregions of the world are grouped into both biomes and ecozones.

Features

Biomes are climatically and geographically defined areas with similar ecological conditions, such as plant and animal communities, (often referred to as ecosystems). Biomes are defined by factors such as plant structure (trees, shrubs, and herbs), leaf types (broadleaf and needle-leaf), plant spacing (closed, open), and climate. Unlike ecozones, biomes are not defined by genetic, taxonomic, or historical similarities. Biomes are often identified with particular patterns of ecological succession and climax vegetation (near-equilibrium state of the local ecosystem). An ecosystem has many biotopes, and a biome is a larger type of habitat. One main type of habitat, however, is a compromise in that it possesses an intrinsic inhomogeneity.

The characteristic biodiversity of each biome, especially the diversity of flora and fauna, is a function of abiotic factors that determine the productivity of the biomass of the dominant vegetation. In terrestrial biomes, species diversity tends to be positively correlated with net primary production, moisture availability, and temperature.

The climatic factor

The biome is fundamentally characterized by climate. It was in fact the zonal distribution of climates that led to the emphasis on land zoning at the end of the 19th century, and then, the biomes.

The physical parameters particularly involved are temperature and precipitation. In turn, the temperature is determined especially with latitude and altitude.

- La latitude: As we move towards high latitudes, the average temperature decreases, So the equatorial, tropical, subtropical, temperate, subpolar and polar climates are defined. In addition in the equatorial areas the temperature differences over the year decrease.

- La altitude: In general, the increase in altitude causes a distribution of habitat types similar to the increase in latitude. So there are certain types of basal, premone, montane, subalpino, alpine and nival.

- Precipitation: which determines wet, subhumid, semi-arid and arid types. In addition, the seasonal variation—the rain may be distributed evenly throughout the year or marked by seasonal variations. In addition, the rainy season can take place in summer, as in most regions of the Earth, or in winter as in the Mediterranean climate regions. Precipitations can also periodically flood both areas by defining a bioma adapted to this phenomenon.

The most widely used biome classification systems correspond to latitude (or temperature zoning) and humidity. In fact, water and temperature —whose distribution on a global scale is largely conditioned by the rotation of the Earth on its axis— are the two key factors for the establishment of a climate that presents, on a global and continental scale, variations according to latitude. This distribution is, therefore, in correlation with homogeneous vegetation bands. These latitudinal bands were first observed by Vasili Dokucháyev, father of Russian soil science, and they were called zones (from the Greek "zonê" meaning waist), which gave birth to the concept of zoning, fundamental in the geography of the natural environment.. Thus, for example, biodiversity is increasing, in general, from the poles to the equator, whether from an animal or plant point of view, as in the case of the dense equatorial forest, which is the richest and most diverse biome.

Similar concepts

The term biome is often confused with other similar ones, such as:

- Habitat: area of uniform environmental conditions that provides vital space for a biological population.

- Biotopo: area of uniform environmental conditions that provides vital space to a certain set of species of flora and fauna (biological community).

- Ecosystem: is a bioma formed by a natural community that is structured with the biotic components (living beings) and the abiotic components (hábitat).

- Ecozone: a part of the representative land area of a large-scale ecological unit characterized by particular abiotic and biotic factors. They are large tracts of the surface of the earth where plants and animals develop for long periods of time in relative isolation, separated from each other by geological characteristics, such as oceans, large deserts, high mountains or mountain ranges, which form barriers to the migration of plants and animals.

- Bioregion: Geographical groups of ecoregions that can encompass various types of habitat, but have strong biogeographic affinities, in particular in taxonomic levels higher than the level of species (gender, family) (WWF definition).

- Ecoregion or ecological region: it is a relatively large geographical area that is distinguished by the unique character of its morphology, geology, climate, soils, hydrology, flora and fauna.

Organization

A biome, in general, groups more than one ecosystem and can be classified into levels of biological organization:

- Biosphere: Maximum biological level.

- Bioma: Higher levels with defined characteristics.

- Community level: Ecosystems or biotopes, i.e. all living beings in a given habitat.

- Population level: formed by all individuals of the same species that can be reproduced among themselves, not those belonging to the same ecosystem separated by any kind of natural barrier.

- Group level: they are associations of individuals of the same species whose objective is to reproduce or obtain a common benefit.

- Body level: collects the individual living being, for example, a rabbit.

- Group level: they are associations of individuals of the same species whose objective is to reproduce or obtain a common benefit.

- Population level: formed by all individuals of the same species that can be reproduced among themselves, not those belonging to the same ecosystem separated by any kind of natural barrier.

- Community level: Ecosystems or biotopes, i.e. all living beings in a given habitat.

- Bioma: Higher levels with defined characteristics.

WWF organizes biological groups as follows:

- Biosphere

- 8 ecozones and 13 marine ecozones

- 14 terrestrial biomas, 12 freshwater biomas and 5 marine biomas

- 238 global ecoregions or bioregions, under the name of Global 200.

- 1.525 ecoregions

- Ecosystems

- 1.525 ecoregions

- 238 global ecoregions or bioregions, under the name of Global 200.

- 14 terrestrial biomas, 12 freshwater biomas and 5 marine biomas

- 8 ecozones and 13 marine ecozones

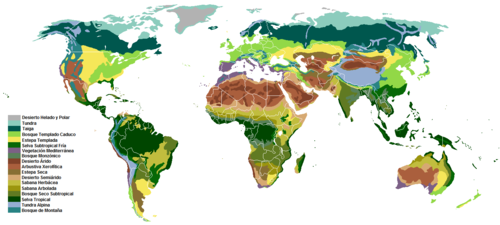

Major biomes of the world

|

Tundra

The primary characteristics of this region are low temperatures (between –15 °C and 5 °C) and a very short favorable season. Rainfall is rather low (about 300 mm per year), but water is not usually a limiting factor, since the rate of evaporation is also very low.

There is an arctic tundra, also called a "polar desert", which extends above 60ºN latitude and an "Antarctic tundra", above 50ºS, which includes Antarctica, the sub-Antarctic islands and part of Patagonia.

Deciduous forest and Mediterranean forest

It occurs in a few regions of the world: Southern Europe, North Africa, the South of the United States and part of South America (Central Chile and Argentina). When the temperatures are warmer and the humidity is more abundant and distributed throughout the year, the coniferous forest is replaced by the deciduous forest. In the Northern Hemisphere this biome is dominated by beeches, oaks, hazelnuts, elms, chestnuts and numerous shrubs that generate deep and fertile soil. In temperate zones, if the rainfall is low and the dry season is very marked, another type of forest is installed, evergreen and resistant to summer drought. It is the Mediterranean forest, with xerophytic vegetation, dominated in Europe by holm oak, cork oak or gall oak.

Deciduous forest climate: We find the deciduous forest around 35º 55º latitude. The typical climate has a moderate thermal regime, abundant rainfall, and well distributed throughout the year and 4 well-defined seasons. Brown soils with little or no leaching and with mull or moderate humus (degradation of the forest to alpine meadow) predominate. Ranker or rendzina soils appear on the slopes, more or less acid, caused by erosion on carbonate bedrock.

Meadow

The prairie biome is found in places with rainfall of 300 to 1,500 mm per year, insufficient to support a forest, and higher than normal for a true desert. Some prairies have been desertified by the action of man. Grassland occurs in the interior of the continents, and the grasslands of the western United States and those of Argentina, Uruguay, and parts of southern Brazil, Australia, southern Russia, and Siberia are well known. The soil of the prairies is very rich in layers by virtue of the rapid growth and decomposition of vegetables, and very suitable for the growth of food plants such as wheat and corn. Other of its characteristics can be:

- Climate: The average daily temperature can range from -20 to 29 °C, with a rainy season and a drought. According to Köppen it belongs to the Aw, BS and Cw types.

- Soil: It is usually alkaline because the water movement is usually upward.

- Vegetation: The predominant vegetation is grasslands and herbaceous plants. The trees, if any, are placed in a single stratum.

Chaparral

Chaparral is also known as Mediterranean forest. In mild climate regions of the world, with relatively abundant winter rainfall but very dry summers, the culminating community includes trees and shrubs with thick, hard leaves. This type of vegetation is called "xerophytic". During hot, dry summers there is a constant danger of fire that can quickly invade the chaparral foothills.

Chaparral communities are extensive in California and northwestern Mexico, along the Mediterranean, in Chile, and along the southern coast of Australia. The diversity of the chaparral, a fairly uniform environment, supports relatively few species, but many of its plants produce edible berries and support vast populations of insects, and what the chaparral loses in diversity it gains in number of individuals. Some characteristic resident vertebrates are small, wood rats, chipmunks, lizards, and others. A characteristic bird of the California chaparral is the Tit Wren (Chamaea fasciata), a species whose range extends beyond the limits of the chaparral.

In the Mediterranean, although the resident animal diversity is not great, that of migratory birds is very great since this region is halfway between the tropics and the more temperate zones. During the summer, the bird population is smaller, with only a few tropical birds, adapted to the bushy habitat and arid conditions. They arrive in the Mediterranean in spring to nest, leaving before the onset of winter. Among winter visitors, passerines (such as warblers and thrushes) and ducks predominate.

Desert

The desert thrives in regions with less than 225 mm of annual rainfall. The characteristics of these areas are:

- The shortage of water and the rains, very irregular, when they fall, make it torrential. In addition, evaporation is very high.

- The soil shortage, which is carried away by the erosion of the wind, favored by the lack of vegetation.

They are not very productive (less than 500 g of carbon per year) and their productivity depends proportionally on the rain that falls. Some deserts are hot, like the Sahara, while others are cold, like the Gobi. In some, the rain is practically non-existent, as in the Atacama, in the Andes. The Atacama is surrounded by high mountains that block the entry of humidity from the sea and favor the appearance of katabatic, dry and descending winds; this phenomenon is known as the Foehn effect. Another climatic mechanism that forms deserts in near-coastal areas is the rise of cold ocean currents near the western continental edges of Africa and South America. The cold water lowers the temperature of the air and they are places where the air descends and does not blow towards the land. In the sea the mists will be frequent, but in the nearby land it will not rain.

The vegetation is widely spaced and the plants usually have repelling mechanisms to ensure that other specimens do not grow nearby.

There are four main forms of desert-adapted plant life:

1. Plants that synchronize their life cycles with the rainy periods and grow only when there is humidity. When it rains with sufficient intensity, its seeds germinate and the plants grow very quickly and form showy flowers. Insects are attracted to flowers and pollinate them by traveling from one to another. Many of these insects also have very short life cycles, adapted to those of the plants on which they feed.

2. Bushes with long roots that penetrate the soil until they reach moisture. They develop especially in cold deserts. Its leaves usually fall before the plant withers completely and in this way it goes into a state of dormant life, until there is moisture in the subsoil again.

3. Plants that accumulate water in their tissues. They are succulent in shape, like cacti or euphorbias, and have thick walls, spikes, and thorns to protect themselves from phytophages. Its rigidity is another way of protecting itself against desiccation caused by the wind.

4. Microflora, which remains dormant until good conditions for its development are produced.

Animal life has also developed very specific adaptations to survive in such a dry environment. The excretions of desert-dwelling animals contain very little water, and many are capable of obtaining water from food. They are nocturnal in habit and during the day they remain in caves and underground burrows. Man has developed cultures that, with great ingenuity, have allowed him to live on the edge of deserts or in desert areas themselves.

When desert land is irrigated, where soils are suitable, it can become one of the most productive agricultural systems. But the cultivation of arid lands usually brings problems of depletion of water sources and salinization, as happened in the ancient Mesopotamian cultures, if systems are not applied to avoid this difficulty. For its exploitation it is necessary to have knowledge of the ecosystem and act accordingly.

Taiga

It occupies a strip more than 1,500 km wide in the northern hemisphere (North America, Europe and Asia) and is also found in mountainous areas.

Very low winter temperatures (less than -40 °C) and a relatively short summer. Scarcity of water (250 mm-500 mm per year) and also remains frozen for many months.

- Vegetation: It consists of conifers (pins, fir), with straight trunks and covered with resin and small leaves similar to needles.

Steppe

The steppe is a biome that includes a flat and extensive territory, with herbaceous vegetation, typical of extreme climates and low rainfall. It is also associated with a cold desert to establish a difference with the hot deserts. These regions are far from the sea, with an arid continental climate, a wide temperature range between summer and winter, and rainfall that does not reach 500 mm per year. Dominated by low bushes and herbs. The soil contains many minerals and little organic matter; There are also areas of the steppe with a high iron oxide content, which gives the earth a reddish hue.

- Climate: It has a dry (similar) climate. High temperatures in summer and low in winter, resulting in a large thermal amplitude as previously said. Rains range from 250 to 500 mm per year.

- Vegetation: is of the xerophile type, that is, plants adapted to the water shortage, with deep roots at the bottom that seek the water pipes.

Rainforest

Tropical forests occupy large areas near the center of the Equator, South America, Africa, Asia and Oceania, and thrive in very humid and hot climates, being provided not only with abundant rainfall, but also with mighty rivers that experience violent floods in autumn. A rain forest is not a 'jungle'. The jungle is a very dense shrubby vegetation that grows along the banks of rivers.[citation needed] It can appear on land when the rainforest has been cleared by humans or by a natural event such as a flood or fire. Most of the jungles are transformed into rain forests. Therefore, the jungle is a humid jungle.

- Vegetation: Large trees and climbing plants (lianas, orchids...)

- Climate: Warm all year, with constant and abundant rainfall.

- Fauna: Great variety of vertebrates and invertebrates.

- Latitude: 0-5° latitude N and S (continuous) and 5-10° latitude North and South (discontinuous).

- Number of species: It is the area with the largest number of organisms, both plant and animal. However, it should be noted that medium and large animal species do not abound.

Savannah

Savannahs are tropical grasslands with a small number of scattered trees or shrubs. They develop in regions of high temperature, which have a marked difference between the dry and wet seasons. In the wet season the growth of the plants is rapid, but they dry out and decline in quality during the dry season. Tropical savannahs cover large areas in South America, Africa, India, Southeast Asia, and Northern Australia. Animal and plant growth in the tropical savannah depends on the different periodic alterations. Large animals migrate in search of water, and their reproductive cycles correspond to the availability of new plant growth. Many animals gather in large herds. A large area of photosynthetic production is necessary to feed these large animals. Regular fire is important for this ecosystem, the maintenance of the meadows depends on it in places where the herds are not so numerous.

- Vegetation: Herbs, scattered trees (flat-top trees) and bushes.

- Climate: Warm, with two seasons, one dry and another rainy.

- Fauna: Handle of herbivores, large carnivores and carnages.

Aquatic Biomes and Coral Reefs

Aquatic biomes can be marine (saltwater) or freshwater (freshwater). The marine biomes are basically the oceanic or pelagic and the littoral or neritic, characterized by the different depth that the water reaches and by the distance from the coast. The coastal zone is characterized by the luminosity of its waters, shallow depth and abundance of nutrients. It is home to algae, molluscs, echinoderms and coral reefs. Turtles, seals and bony fish are very common in this area. The pelagic zone is characterized by having an illuminated band but also great depths without light. In these regions, aquatic beings have adapted to living without it and to being subjected to great pressures.

Freshwater biomes are basically the still (lentic) waters of lakes and lagoons and the flowing (lotic) waters of rivers and streams. Of the surface of the planet, 70% of its surface is occupied by the oceans. Of the remaining 30%, which corresponds to emerged lands, 11% of that surface is covered by ice, which can be classified as frozen desert, and 10% is occupied by tundra.

Mangrove Swamp

Mangroves are salt-tolerant tree biomes that grow on shorelines where sea levels rise and fall. These trees generate dry land naturally by accumulating sand particles and mangrove leaves on the ground and when the tide goes out forming swampy land.

Classification

The need for a biome classification system arose after the creation of climate classification systems, which were based solely on meteorological criteria such as rainfall and insolation. The first bioclimatic classifications were born in the 1950s with the Holdridge classification. Pioneering classification systems tried to define biomes using climatic measurements. Then, in the 1970s and 1980s, there was a major push to understand the relationships between these parameters and the energetic properties of ecosystems, because such discoveries would allow the prediction of rates of energy capture and transfer between different components of ecosystems. ecosystems.

One such study was conducted by Sims et al. (1978) on the North American prairies. The study found a positive correlation between evapotranspiration, in mm/year, and net primary production above ground in g/m²/year. Other general results of the study were that precipitation and water use lead to primary production on the ground; that solar radiation and temperature lead to underground primary production (roots); and that temperature and water lead to warm and cool season seasonal growth habitats. These results help explain the categories used in Holdridge's bioclassification system, which were later simplified in Whittaker's.

Ecological classifications became more and more precise and detailed, and several countries wanted to have their own classification system. The number of classification systems and the wide variety of determinants used should be taken as an indicator that not all biomes fit perfectly into the classification systems created and that the classifications made are not equivalent, since the criteria chosen for the classification The definition of the zones fulfill different objectives depending on whether they are the States or the organizations that choose them. Thus, the United States has established classifications such as the United States National Vegetation Classification Standard ("United States National Vegetation Classification Standard") within the framework of the Commission for Environmental Cooperation ("Commission de coopération environnementale"), which will help define biomes.

Defined biomes are precisely enumerated, allowing you to define a precise protection policy. The important places for each biome were listed in databases of the type of the European database Corine Biotope ("Corine Biotope"), today replaced by that of the European Union Nature Information System (EUNIS). The biomes used by the European Union are listed on the Digital Map of the European Ecological Region (“Digital Map European Ecological Region”, DMEER) or by the Environmental classification of Europe (CNE). Sometimes an entire biome can be protected, especially by individual action by a nation, through the development of a Biodiversity Action Plan (BAP).

Holdridge system

The Holdridge Classification System is a project for the classification of different terrestrial areas according to their global bioclimatic behavior. It was developed by the American botanist and climatologist Leslie Holdridge (1907-99) and was first published in 1947 (with the title of Determination of World Plant Formations from Simple Climatic Data) and later updated in 1967 (Life Zone Ecology). It uses the concept of life zone and is based on the following factors:

- Annual average biotemperature (in logarithmic scale). In general, it is estimated that the vegetative growth of plants occurs in a temperature range between 0 °C and 30 °C, so that biotemperature is a corrected temperature that depends on the very temperature and duration of the growth station, and in which the temperatures below the freezing temperature are taken as 0 °C, as the plants are fined at those temperatures.

- Annual precipitation in mm (in logarithmic scale).

- The relationship of potential evapoperspiration (EPT)—which is the relationship between evapoperspiration and annual average precipitation—is a humidity index that determines the provinces of humidity ('humidity provinces').

In this system, biogeographic zones are classified according to the biological effects of temperature and precipitation on vegetation, assuming that these two abiotic factors are the main determinants of the type of vegetation found in a zone. Holdridge uses 4 axes (biotemperature, precipitation, altitudinal floor and latitudinal region) to define the 30 so-called "moisture provinces", which are clearly visible on the Holdridge plot. Since his classification largely ignored soil and sun exposure, Holdridge recognized that these elements were important factors, too, in determining biomes.

Whittaker's Biome Type Classification Scheme

Robert Harding Whittaker (1920-80), American ecologist and botanist, appreciated the existence of biome types as a representation of the great diversity of the living world, and saw the need for a simple way to classify those types of biomes. biomes. Whittaker based his classification system on two abiotic factors: temperature and precipitation. His scheme can be considered as a simplification of Holdridge's, more easily accessible, but perhaps missing the greater specificity that Holdridge's provides.

Whittaker bases his representation of the world's biomes on the above two theoretical statements, as well as on increasing empirical sampling of the world's ecosystems. Whittaker was in a unique position to make such a holistic claim since he had previously compiled a review of biome classification.

The key concepts for understanding the Whittaker scheme are the following:

- Physiognomy: the apparent characteristics, external features or appearance of ecological communities or species.

- Bioma (“biome”): a grouping of terrestrial ecosystems in a given continent, which are similar in vegetation structure, physiognomy, environmental characteristics and characteristics of their animal communities.

- Formation (“formation”): a larger class of plant community from a given continent.

- Type of bioma (biome-type): grouping of convergent biomas or formations of different continents; defined by physiognomy.

- Type of formation (“formation-type”): grouping of convergent formations.

Whittaker's distinction between biome and formation can be simplified: formation is used when it applies only to plant communities, while biome is used when dealing with both plants and animals. Whittaker's convention of biome type or formation type is simply a broader method for classifying similar communities. The world's biome types, shown on a world map, can be seen at the following link: here Archived 13 April 2009 on the Wayback Machine.

Whittaker parameters for the classification of biome types

Whittaker, seeing the need for a simpler way to express the relationship of community structure to the environment, uses what he called "gradient analysis" of ecocline patterns. to link communities to climate on a global scale. Whittaker considers four major ecoclines in the terrestrial realm:

- 1. Intermareal levels: the humidity gradient of the areas that are exposed to the alternation of water and dryness, with intensity that vary according to the location of low to high tide.

- 2. Climate humidity gradient.

- 3. Temperature gradient per altitude.

- 4. Temperature gradient by latitude.

Along these gradients, Whittaker found several trends that allowed him to qualitatively establish biome types.

- The gradient goes from favorable to extreme with corresponding changes in productivity.

- Changes in physionomic complexity vary with favorability of the environment (decreasing the structure of the community and reducing the differentiation of strata when the environment is less favorable).

- Trends in the diversity of the structure follow trends in the diversity of species; the diversity of alpha and beta species decreases from pro-end environments;

- Each form of growth (i.e. herbs, bushes, etc.) has its characteristic place of utmost importance along the ecoclines.

- The same forms of growth can be dominant in similar environments in very different parts of the world.

Whittaker summarizes the effects of gradients (3) and (4) by arranging a joint temperature gradient and combines this with the moisture gradient (2), to express the above conclusions in what is known as the Classification Scheme. of Whittaker ("Whittaker Classification Scheme"). The scheme plots mean annual precipitation (x-axis) versus mean annual temperature (y-axis) to classify biome types.

Walter's System

The Heinrich Walter classification system was developed by Heinrich Walter, a German ecologist. It differs from both the Holdridge and Whittaker regimes in that it takes into account the seasonality of temperature and precipitation. The system, also based on precipitation and temperature, finds 9 large biomes, whose most important features of climate and vegetation types are summarized in the attached table. The limits of each biome are correlated with the conditions of humidity and cold that are important determinants of the form of the plants and, therefore, of the vegetation that defines the region.

| Type | Climate | Vegetable |

|---|---|---|

| I. Equatorial Guinea | Always humid and lacking seasonal temperature | Tropical rainforest alwaysgreen; |

| II. Tropical | Rainy summer season and more cold and dry winter | Seasonal forest, scrub or savannah; |

| III. Subtropical | Highly seasonal, arid climate | Desert vegetation with a considerable exposed surface; |

| IV. Mediterranean | Winter season of rain and a summer with drought | Sclerophiles (adapted to drought), scrubs and frost-sensitive forests; |

| V. Warm season | Occasional ice cream, often with maximum summer rains | Tempered forest alwaysgreen, not sensitive to frosts; |

| VI. Nemoral | Moderate climate with winter frosts | Tempered, deciduous, frost resistant forest; |

| VII. Continental | Hot or hot summers and cold winters | Tempered pastures and deserts; |

| VIII. Boreal | Cold season, with fresh summers and long winters | Alwaysgreen, with frost resistant needle forests (taiga); |

| IX. Polar | Fresh summers very short and long cold winters | Low vegetation, perennial without trees, growing in permanently frozen soils. |

Bailey's system

Robert G. Bailey nearly developed a biogeographic classification system for the United States in a map published in 1976. Bailey later expanded the system to include the rest of South America in 1981 and the world in 1989. The system of Bailey is based on climate and is divided into seven domains (polar, temperate humid, dry, humid, and tropical humid), with further divisions based on other climatic features (subarctic, warm temperate, warm temperate, and subtropical; marine and continental; land low and mountain).

| Dominion | Division | Province |

|---|---|---|

| 100 Domain Polar (“Polar Domain”) | 120 Tundra Division | M120 Tundra Division - Mountain Provinces |

| 130 Sub-arctic Division | M130 Subarctic Division - Mountain Provinces | |

| 200 Sunset Domain (Humid Temperate Domain) | 210 Warm Continental Division (Warm Continental Division) | M210 Warm continental division - Mountain provinces |

| 220 Hot Continental Division (Hot Continental Division) | M220 Hot Continental Division - Mountain Provinces | |

| 230 Subtropical Division | M230 Subtropical Division - Mountain Provinces | |

| 240 Marine Division (Marine Division) | M240 Marine Division - Mountain Provinces | |

| 250 Pradera Division (“Prairie Division”) | ||

| 260 Mediterranean Division (Mediterranean Division) | M260 Mediterranean Division or - Mountain Provinces |

WWF System

A team of biologists convened by the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) has developed an ecological classification system in which the so-called «Major Habitat Types», similar to biomes, were identified. after analyzing the 867 terrestrial ecoregions into which the Earth was divided. Each of these terrestrial ecoregions has an identification number or EcoID, with a format of the type XXnnNN (where XX is the Ecozone, nn is the biome number and NN is the individual number of the ecoregion). This classification is used to define the Global 200 list of ecoregions identified by WWF as priorities for conservation.

The WWF organizes biomes into two large groups, terrestrial and marine biomes, and terrestrial biomes, in turn, into two subgroups, terrestrial biomes proper and freshwater biomes. Although marine biomes do exist, they meet much less zoning criteria—because of the large currents that cross the oceans at all levels of depth—and are more difficult to define in space. In the sense of biome as it has been defined, the study of aquatic environments would preferably fall into oceanography —study of the seas— or limnology —study of fresh waters.

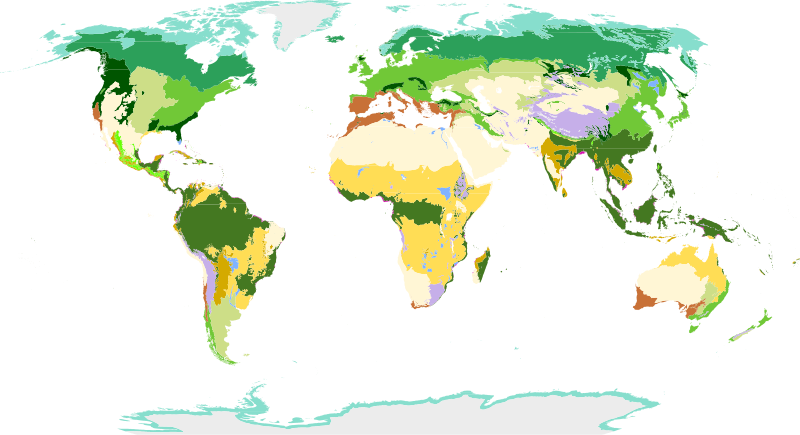

WWF has identified 14 major terrestrial, 12 freshwater, and 7 marine habitat types. The terrestrial ones are collected in the following map and all of them in the corresponding table (the color code does not have a standard that unifies it, so it is adapted to the attached map).

| Group | Subgroup | Go. | Denomination | Denomination in English | Climate | N.o ecoregiones |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Terrestrials | Terrestrials | 01 | Tropical and subtropical rainforest | Tropical and subtropical moist broadleaf forests | Tropical and subtropical, wet | 231 ecoregions |

| 02 | Tropical and subtropical dry forest | Tropical and subtropical dry broadleaf forests | Tropical and subtropical, semi-humid | 59 ecoregions | ||

| 03 | Subtropical Coniferous Forest | Tropical and subtropical coniferous forests | tropical and subtropical, semi-humid | 17 ecoregions | ||

| 04 | Tempered hardwood and mixed | Temperate broadleaf and mixed forests | Tempered, wet | 84 ecoregions | ||

| 05 | Coniferous temperate forest | Temperate coniferous forests | Cold temper, wet | 52 or 53 ecoregions | ||

| 06 | boreal forest/Taiga | Boreal forests/taiga | Subarctic, wet | 28 ecoregions | ||

| 07 | Tropical and subtropical grasslands, savannahs and matorals | Tropical and subtropical grasslands, savannas, and shrublands | Tropical and subtropical, semi-arid | |||

| 08 | Tempered grasslands, steppes and bushes | Temperate grasslands, savannas, and shrublands | temperate, semi-arid | |||

| 09 | Flooded grasslands and savannahs | Flooded grasslands and savannas | temperate to tropical, fresh water or flooded salt | 26 ecoregions | ||

| 10 | Mountain slopes and bushes | Montane grasslands and shrublands | Alpine or mountain climate | 50 ecoregions | ||

| 11 | Tundra | Tundra | Arctic | 37 ecoregions | ||

| 12 | Mediterranean forest and scrub | Mediterranean forests, woodlands, and scrub | warm temperate, semi-humid to semi-arid with winter rainfall) | 39 to 50 ecoregions | ||

| 13 | Desert and xerophile bush | Deserts and xeric shrublands | Tempered to tropical, arid | 99 ecoregions | ||

| 14 | Manglar | Mangrove | subtropical and tropical, flooded with salt water | 50 ecoregions | ||

| Sweet water | - | Great lakes | Large lakes | - | 4 ecoregions | |

| - | Great cans | Large river deltas | - | 6 ecoregions | ||

| - | Polar sweet water | Polar freshwaters | - | |||

| - | Fresh mountain water | Montane freshwaters | - | |||

| - | Tempered coastal rivers | Temperate coastal rivers | - | |||

| - | Flood plains and tempered wetlands | Temperate floodplain rivers and wetlands | - | |||

| - | Rivers temperate upstream | Temperate upland rivers | - | 5 ecoregions | ||

| - | Tropical and subtropical coastal rivers | Tropical and subtropical coastal rivers | - | |||

| - | Flood plains and tropical and subtropical wetlands | Tropical and subtropical floodplain rivers and wetlands | - | |||

| - | Tropical and subtropical rivers upstream | Tropical and subtropical upland rivers | - | |||

| - | Hot water and endorreal basins | Xeric freshwaters and endorheic basins | - | 3 ecoregions | ||

| - | Ocean Islands | Oceanic islands | - | |||

| Marine | Coast and continental shelf | - | Polar | Polar | - | 3 ecoregions |

| - | Tempered platforms and sea | Temperate shelves and sea | - | 9 ecoregions | ||

| - | Tempered surgeries | Temperate upwelling | - | 5 ecoregions | ||

| - | Tropical species | Tropical upwelling | - | 5 ecoregions | ||

| - | Tropical coral | Tropical coral | - | 22 ecoregions | ||

| Open and deep sea | - | Open & Deep Sea |

The way to classify the ecoregions of the WWF responds to the following scheme:

| Domain (Realms) | Types of Major Habitat Types | Ecoregions | Ecosystems (biotopes) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biosphere | Ecozones (8) | Ground biomas (14) | - | Ecoregions (867) | |

| Water biomas (12) | - | Ecoregions (426) | |||

| Marine ecosystems (13) | Biomass continental shelf (5) | (Navy Provinces) (62) | Ecoregions (232) | ||

| Open and deep sea biomas | |||||

| Endolitic biomas |

FAO Ecological Zones

The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations, has developed world ecological and forest maps that give a spatial and statistical definition, providing a vision of the world forest cover, which provides an important means for add global information on natural resources according to their ecological characteristics.

The following map is inspired by the ecological zones or ecozones of the FAO:

Contenido relacionado

Human genome

Bacteriology

Tulip