Biological evolution

of living beings |

| Key topics |

|---|

|

| Processes and consequences |

|

| History |

|

| Fields and applications |

|

The biological evolution is the set of changes in phenotypic and genetic characteristics of biological populations through generations. This process has originated the diversity of life forms that exist on Earth from a common ancestor. Evolutionary processes have produced biodiversity at every level of biological organization, including species, population, individual organisms, and molecular (molecular evolution), shaped by repeated formations of new species (speciation), changes within species (anagenesis) and disappearance of species (extinction). Morphological and biochemical traits are more similar among species that share a more recent common ancestor and can be used to reconstruct phylogenetic trees. The fossil record shows rapid moments of speciation interspersed with relatively long periods of stasis showing few evolutionary changes during most of its geological history (punctuated equilibrium). All life on Earth derives from a universal last common ancestor that existed approximately 4.35 billion years ago.

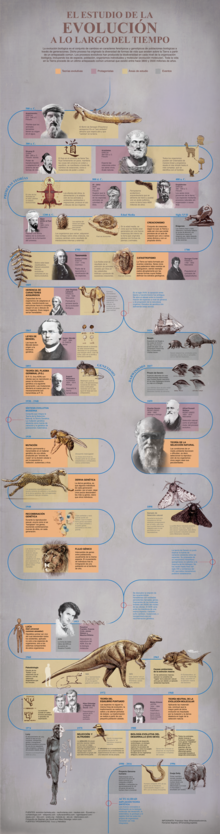

The word "evolution" is used to describe changes and was first applied in the 18th century by a Swiss biologist, Charles Bonnet, in his work Consideration sur les corps organisés. Life on Earth evolved from a common ancestor had already been formulated by several Greek philosophers, and the hypothesis that species continually transform was postulated by numerous 18th and 19th century scientists, cited by Charles Darwin in the first chapter of his book The Origin of Species. Some ancient Greek philosophers contemplated the possibility of changes in organisms over time.

Naturalists Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace independently proposed in 1858 that natural selection was the basic mechanism responsible for the origin of new genotypic variants and ultimately new species. However, it was Darwin himself. in The Origin of Species, who synthesized a coherent body of observations and deepened the mechanism of change called natural selection, which consolidated the concept of biological evolution into a true scientific theory. Previously, the concept of natural selection had already been contributed in the 9th century by Al-Jahiz (776-868), in his Book of Animals, with key postulates on the fight for the survival of species, and the inheritance of successful traits through reproduction.

Since the 1940s, the theory of evolution combines the proposals of Darwin and Wallace with Mendel's laws and other later advances in genetics; This is why it is called the modern synthesis or "synthetic theory". According to this theory, evolution is defined as a change in the frequency of alleles in a population over generations. This change can be caused by different mechanisms, such as natural selection, genetic drift, mutation, and migration or gene flow. The synthetic theory currently receives general acceptance from the scientific community, although there are also some criticisms such as the fact that it does not incorporate the role of niche construction and extragenetic inheritance. Advances in other related disciplines, such as molecular biology, developmental genetics, or paleontology, have enriched synthetic theory since its formulation around 1940.

In the 19th century, the idea that life had evolved was a topic of intense academic debate focused on the philosophical, social, and religious implications of evolution. Evolution as an inherent property of living beings is not a matter of debate in the scientific community dedicated to its study; however, the mechanisms that explain the transformation and diversification of species are under intense and continuous scientific investigation, emerging new hypotheses. on the mechanisms of evolutionary change based on empirical data taken from living organisms.

Evolutionary biologists have continued to study various aspects of evolution by formulating hypotheses as well as constructing theories based on evidence from the field or laboratory and on data generated by the methods of mathematical and theoretical biology. His discoveries have influenced not only the development of biology, but many other scientific and industrial fields, including agriculture, medicine, and computer science.

Evolution as a proven fact

Evolution is as much a "fact" (an observation, measurement, or other form of evidence) as a "theory" (a comprehensive explanation of some aspect of nature that is supported by a large body of evidence). The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine states that the theory of evolution is "a scientific explanation that has been tested and confirmed so many times that there is no compelling reason to continue. trying it out or looking for additional examples".

Evidence of the evolutionary process

Evidence for the evolutionary process comes from the body of evidence scientists have assembled to show that evolution is a process characteristic of living matter and that all organisms living on Earth descend from a universal last common ancestor. Existing species are a stage in the evolutionary process, and their relative richness and levels of biological complexity are the product of a long series of speciation and extinction events.

The existence of a common ancestor can be deduced from a few simple characteristics of the organisms. First, there is evidence from biogeography: both Charles Darwin and Alfred Russell Wallace realized that the geographic distribution of different species depends on the distance and isolation of the areas they occupy, and not on similar ecological and climatic conditions, as would be the case. to be expected if the species had appeared at the same time already adapted to their environment. Later, the discovery of plate tectonics was very important for the theory of evolution, providing an explanation for the similarities between many groups of species on continents that were united in the past. Second, the diversity of life on the Earth does not resolve into a completely unique set of organisms, but rather they share a great number of morphological similarities. Thus, when the organs of different living beings are compared, similarities are found in their constitution that indicate the relationship that exists between different species. These similarities and their origin allow organs to be classified into homologues, if they have the same embryonic and evolutionary origin, and analogous, if they have a different embryonic and evolutionary origin, but the same function. Anatomical studies have found homology in many structures superficially so different, such as the spines of cacti and the traps of various insectivorous plants, indicating that they are simply leaves that have undergone adaptive modifications. Evolutionary processes also explain the presence of vestigial organs, which they are reduced and have no apparent function, but clearly show that they are derived from functional organs present in other species, such as the rudimentary hind leg bones present in some snakes.

Embryology, through comparative studies of the embryonic stages of different kinds of animals, offers another set of clues to the evolutionary process. It has been found that in these early stages of development, many organisms show common features that suggest the existence of a shared development pattern between them, which, in turn, suggests the existence of a common ancestor. The fact that early embryos of vertebrates such as mammals and birds have gill slits, which then disappear as development progresses, can be explained by their being related to fish.

Another set of clues comes from the field of systematics. Organisms can be classified using the above similarities into hierarchically nested groups, much like a family tree. While modern research suggests that due to horizontal gene transfer, this tree of life may be more complicated than expected. than previously thought, as many genes have been distributed independently among distantly related species.

Species that have lived in ancient times have left records of their evolutionary history. Fossils, together with the comparative anatomy of current organisms, constitute the paleontological evidence of the evolutionary process. By comparing the anatomies of modern species with those already extinct, paleontologists can infer the lineages to which one and the other belong. However, paleontological research to search for evolutionary connections has certain limitations. In fact, it is useful only in those organisms that have hard body parts, such as shells, teeth, or bones. Furthermore, certain other organisms, such as prokaryotes -bacteria and archaea- have a limited number of common characteristics, so their fossils do not provide information about their ancestors.

A more recent method of proving the evolutionary process is the study of biochemical similarities between organisms. For example, all cells use the same basic set of nucleotides and amino acids. The development of molecular genetics has revealed that the evolutionary record resides in the genome of each organism and that it is possible to date the time of species divergence to through the molecular clock based on mutations accumulated in the process of molecular evolution. For example, the comparison between human and chimpanzee DNA sequences has confirmed the close similarity between the two species and has helped to elucidate when the ancestor existed common to both.

The origin of life

The origin of life, although it concerns the study of living beings, is a subject that is not addressed by the theory of evolution; since the latter only deals with the change in living beings, and not with the origin, changes and interactions of the organic molecules from which they come.

Not much is known about the earliest and pre-developmental stages of life, and attempts to unravel the earliest history of the origin of life generally focus on the behavior of macromolecules, because the current scientific consensus is that the complex biochemistry that makes up life arose from simple chemical reactions, although controversy remains about how these occurred. However, scientists agree that all existing organisms share certain characteristics ― including the presence of cell structure and genetic code― that would be related to the origin of life.

It is also unclear what were the first developments of life (protobionts), the structure of the first living things, or the identity and nature of the last universal common ancestor. Bacteria and archaea, the first organisms to leave a trace in the fossil record, they are too complex to have arisen directly from non-living materials. The lack of geochemical or fossil clues to earlier organisms has left a wide field for hypotheses. Although there is no scientific consensus on how life began, the existence of the last universal common ancestor is accepted because it would be virtually impossible that two or more separate lineages could have independently evolved the many complex biochemical mechanisms common to all living organisms.

It has been proposed that the start of life may have been self-replicating molecules such as RNA, or assemblies of simple cells called nanocells. Scientists have suggested that life arose in deep-sea hydrothermal vents, geysers, or fumaroles during the Hadic. An alternative hypothesis is that of the beginning of life in other parts of the Universe, from where it would have reached Earth in comets or meteorites, in the process called panspermia.

The evolution of life on Earth

Detailed chemical studies based on carbon isotopes of Archean rocks suggest that the first forms of life emerged on Earth probably more than 4.35 billion years ago, at the end of the Hadic eon, and there are clear geochemical clues ―such as the presence in ancient rocks of sulfur isotopes produced by the microbial reduction of sulfates—indicating their presence in the Paleoarchic era, three thousand four hundred and seventy million years ago. Stromatolites—layers of rock produced by communities of microorganisms—older they are recognized in 3.7 billion-year-old strata, while the oldest threadlike microfossils are found in semi-mentary rocks from 3.77–4.28 billion-year-old hydrothermal vents found in Canada.

Furthermore, molecular fossils derived from the lipids of the plasma membrane and the rest of the cell – called 'biomarkers' – confirm that certain cyanobacteria-like organisms inhabited the archean oceans more than 2.7 billion years ago. These photoautotrophic microbes released oxygen, which began to accumulate in the atmosphere approximately 2.2 billion years ago and permanently transformed its composition. The emergence of an oxygen-rich atmosphere following the rise of photosynthetic organisms can also be traced by layered deposits of iron and the red bands of later iron oxides. The abundance of oxygen enabled the development of aerobic cellular respiration, which emerged approximately 2 billion years ago.

From the formation of these first complex life forms, the prokaryotes, 4.25 billion years ago, billions of years passed without any significant change in cellular morphology or organization in these organisms, until the advent of eukaryotes from the integration of an archaea of the Asgard clade and an alphaproteobacteria forming a cooperative association called endosymbiosis. Eukaryotes are cladistically considered one more clade within the archaea. Bacteria incorporated into archaean host cells, initiated a process of coevolution, by which bacteria gave rise to mitochondria or hydrogenosomes in eukaryotes. It is also postulated that a giant poxvirus-like DNA virus gave rise to the nucleus of eukaryotic cells by having the virus incorporated into the cell where instead to replicate and destroy the host cell, it would remain inside the cell, later giving rise to the nucleus and giving birth gar to other genomic innovations. This theory is known as 'viral eukaryogenesis'. Both molecular and paleontological evidence indicates that the first eukaryotic cells arose around 2.5 billion years ago.

A second independent event of endosymbiosis occurred 2.1-1.9 billion years ago which led to the formation of chloroplasts from cyanobacteria and a protozoan which would give rise to red algae and green algae, later to algae. Green plants that managed to leave the aquatic environment evolved during the Cambrian. On the other hand, other algae such as diatoms or brown algae obtained their chloroplasts by secondary endosymbiosis between protozoa with red or green algae, but evolutionarily they are not related to red or green algae.

Multicellular life arose from the colonial union of microorganisms to manage to form fruitful organs, tissues and bodies. According to molecular and structural analyses, the animals originated from a colonial union of protozoa similar to choanophlegellae forming crowns of microvilli and with a tendency to cellular specialization, choanoflagellates are protozoa similar to animal spermatozoa and choanocyte-like cells. presented by some animals that are genetically the closest protists to animals. The fungi evolved from amoeboid parasitic protozoa that, due to their parasitism, lost phagocytosis, being replaced by osmosis and had a tendency to form filamentous colonies. Fungi and animals are the kingdoms of nature that are genetically closest to each other and are grouped together in the Opisthokonta clade along with their closest protozoa. In addition, its cells are uniflagellate and opisthoconta similar to spermatozoa. Although more evolved fungi such as mushrooms or molds lack flagella in their cells, this is preserved in more primitive fungi such as chytrids or microsporidia, so fungi evolved from ancestors similar to those of animals. Slime molds could be a better model of how one can transition from unicellular to multicellular life, since certain plasmodial amoebas can group together in colonies and form a fruiting body capable of sliding across the ground. On the other hand, myxobacteria when grouped together in colonies can form small fruiting bodies like amoebas, thus this shows that multicellularity can be gained not only in eukaryotes, but also in prokaryotes.

The oldest fossils that would be considered eukaryotes correspond to the 2.1 billion-year-old biota of France, which were probably slime molds that would represent the first indications of multicellular life. The organisms measured around 12 cm and consisted of flat disks with a characteristic morphology and included circular and elongated individuals. In certain aspects they are similar to some organisms of the Ediacaran Biota. In addition, according to scientific studies, they could have a multicellular life state and a unicellular one, since they would develop from cellular aggregates capable of forming plasmodial fruiting bodies.

The history of life on Earth was that of single-celled eukaryotes, bacteria, and archaea until about 580 million years ago, when the first multicellular organisms appeared in the oceans in the Ediacaran period. These organisms are known as the Biota of the Ediacaran period.

It is possible that some Ediacaran organisms were closely related to groups that predominated later, such as porifera or cnidarians. However, due to the difficulty in deducing evolutionary relationships in these organisms, some paleontologists have suggested that the Ediacaran biota represents a completely extinct branch, a "failed experiment" of multicellular life, and that later multicellular life later re-evolved from unrelated unicellular organisms. In any case, the evolution of organisms Multicellular microorganisms occurred in multiple independent events, in organisms as diverse as sponges, brown algae, cyanobacteria, slime fungi, and myxobacteria.

Shortly after the appearance of the first multicellular organisms, a great diversity of life forms appeared in a period of ten million years, in an event called the Cambrian explosion, a brief period in geological terms, but one that implied a diversification animal with no parallel documented in fossils found in the sediments of the Burgess Shale, Canada. During this period, most of today's animal phyla appeared in the fossil record, as well as a large number of unique lineages that subsequently became extinct. Most modern animal body plans originated during this period.

Possible triggers for the Cambrian Explosion include the buildup of oxygen in the atmosphere due to photosynthesis.

Approximately 500 million years ago, plants and fungi colonized the land and were quickly followed by arthropods and other animals.

Amphibians appeared in Earth's history about 300 million years ago, followed by the first amniotes, then mammals about 200 million years ago, and birds about 150 million years ago. However, microscopic organisms, similar to those that evolved early, continue to be the predominant form of life on Earth, as most species and terrestrial biomass are made up of prokaryotes.

History of evolutionary thought

Several ancient Greek philosophers contemplated the possibility of changes in living organisms over time. Anaximander (ca. 610-546 BCE) suggested that the first animals lived in water and gave rise to land animals. Empedocles (ca. 490-430 BCE) wrote that the first living things came from of the earth and species arose through natural processes without an organizer or final cause. Such proposals survived until Roman times. The poet and philosopher Lucretius, followed Empedocles in his masterpiece De rerum natura (On the nature of things) where the universe works through naturalistic mechanisms, without any supernatural intervention. If the mechanistic vision is found in these philosophers, the teleological vision occurs in Heraclitus, who conceives the process as a rational development, in accordance with the Logos. Development, as well as the process of becoming, in general, was denied by the Eleatic philosophers.

The works of Aristotle (384-322 BC), the first naturalist whose work has been preserved in detail, contain very astute observations and interpretations, albeit mixed with various myths and errors that reflect the state of knowledge in his time; his effort is notable in exposing the existing relationships between living beings as a scala naturae ―as described in Historia animalium― in which organisms are They are classified according to a hierarchical structure, "ladder of life" or "chain of Being", ordered according to the complexity of their structures and functions, with organisms that show greater vitality and capacity for movement described as "higher organisms". In contrast to these materialist views, Aristotelianism viewed all natural things as actualizations of fixed natural possibilities, known as forms. This was part of a teleological understanding of nature in which all All things have a role they are destined to play in a divine cosmic order. The entire transition from potentiality to actuality (fromdynamis to entelecheia) is nothing more than a transition from the lower to the higher, to the perfect, to the Divine. Aristotle criticized Empedocles' materialistic theory of evolution, in which random accidents could lead to orderly outcomes, however he did not argue that species cannot change or become extinct, and accepted that new types of animals can occur in very rare cases.

The Stoics followed Heraclitus and Aristotle in the main lines of their physics. With them, the whole process is carried out according to the purposes of the Divine. Variations of this idea became the standard understanding of the Middle Ages and were integrated into Christianity. Saint Augustine takes an evolutionary view as his basis. for his philosophy of history. Erigena and some of her followers seem to teach a kind of evolution. Thomas Aquinas did not detect any conflict in a divinely created universe and developed over time through natural mechanisms, arguing that the autonomy of nature was a sign of God (Fifth Way).

Some ancient Chinese thinkers also expressed the idea that biological species change. Zhuangzi, a Taoist philosopher who lived around the 4th century B.C. C., mentioned that life forms have an innate ability or power (hua 化) to transform and adapt to their environment.

According to Joseph Needham, Taoism explicitly denies the immutability of biological species and Taoist philosophers speculated that they developed different attributes in response to different environments. In fact, Taoism refers to humans, nature, and the sky as existing in a state of "constant transformation", in contrast to the more static view of nature typical of Western thought.

While the idea of biological evolution has been around since ancient times and in different cultures — for example, it was first outlined in Muslim society in the 19th century IX Al-Jahiz and in the XIII Nasir al-Din al-Tusi century respectively—, The modern theory was not established until the 18th and 19th centuries, with contributions from scientists such as Christian Pander, Jean-Baptiste Lamarck, and Charles Darwin.

In the 17th century, the new method of modern science rejected the Aristotelian approach, the idea of final causes. He sought explanations of natural phenomena in terms of physical laws that were the same for all visible things and that did not require the existence of any fixed natural category or cosmic divine order. In biology, however, teleology persisted for longer, that is, the view according to which there are ends in nature. This new approach was slow to take root in the biological sciences, the last bastion of the concept of fixed natural types. John Ray applied one of the previously most general terms for fixed natural types, "species", to the types of plants and animals, but he strictly identified each type of living thing as a species and proposed that each species could be defined by characteristics that perpetuated themselves generation after generation. The biological classification introduced by Charles Linnaeus in 1735 explicitly recognized the hierarchical nature of relationships between species, but still regarded species as fixed according to a divine plan.

In the 18th century, the opposition between fixism and transformism was ambiguous. Some authors, for example, admitted the transformation of species at the genus level, but denied the possibility that they changed from one genus to another. Other naturalists spoke of "progression" in organic nature, but it is very difficult to determine if with this they were referring to a real transformation of the species or it was simply a modulation of the classical idea of scala naturae< /i>. Among the German philosophers, Herder established the doctrine of a continuous development in the unity of nature, from the inorganic to the organic, from the stone to the plant, from the plant to the animal and from the animal to man. Kant is also often mentioned as one of the first teachers of the modern theory of descent.

Georges-Louis Leclerc de Buffon (1707-1788) suggested that species could degenerate into different organisms, and Erasmus Darwin (1731-1802) proposed that all warm-blooded animals could have descended from a single microorganism (or & #34;filament").

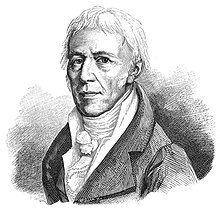

Jean-Baptiste Lamarck (1744-1829) formulated the first theory of evolution or "transmutation" and proposed that organisms, in all their variety, had evolved from simple forms created by God and He postulated that those responsible for this evolution had been the organisms themselves due to their ability to adapt to the environment: changes in that environment generated new needs in the organisms and these new needs would entail a modification of them that would be heritable. He relied for the formulation of his theory on the existence of remains of extinct intermediate forms. With this theory, Lamarck faced the general belief that all species had been created and remained unchanged since their creation and also opposed the influential Georges Cuvier (1769-1832) who justified the disappearance of species not because they were intermediate forms between the original and the current ones, but because they were different forms of life, extinguished in the different geological cataclysms suffered by the Earth. While Thus, the ideas of John Ray and of benevolent design had been developed by William Paley in Natural Theology (1802), who proposed complex adaptations as evidence of divine design and who was admired by Charles Darwin.

It was not until the publication of Charles Darwin's On the Origin of Species that the fact of evolution began to be widely accepted. A letter from Alfred Russel Wallace, in which he revealed his own discovery of natural selection, prompted Darwin to publish his work on evolution. Therefore, both are sometimes given credit for the theory of evolution, also calling it the Darwin-Wallace theory.

A particularly interesting debate in the evolutionary field was held by the French naturalists Georges Cuvier and Étienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire in the year 1830. Both disagreed on the fundamental criteria to describe the relationships between living beings; while Cuvier relied on functional anatomical features, Geoffroy gave more importance to morphology. The distinction between function and form led to the development of two fields of research, known respectively as functional anatomy and transcendental anatomy. Thanks to the work of the British anatomist Richard Owen, the two views began to be reconciled, a process completed in Darwin's theory of evolution.

Although Darwin's theory profoundly shook scientific opinion regarding the development of life, even having social influences, it could not explain the source of variation between species, and furthermore Darwin's proposal of the The existence of a hereditary mechanism (pangenesis) did not satisfy most biologists. It was not until the late 19th century and early 20th century that these mechanisms could be established.

When around 1900 the work of Gregor Mendel at the end of the 19th century on the On the nature of heredity, a dispute ensued between the Mendelians (Charles Benedict Davenport) and the biometricians (Walter Frank Raphael Weldon and Karl Pearson), who insisted that most of the pathways important to evolution must show continuous variation that does not exist. It was explainable through Mendelian analysis. Eventually the two models were reconciled and merged, primarily through the work of biologist and statistician Ronald Fisher. This combined approach, which applied a rigorous statistical model to Mendel's theories of inheritance via genes, became known in the 1930s and 1940s and is known as the synthetic theory of evolution.

In the 1940s, following Griffith's experiment, Avery, MacLeod, and McCarty were able to definitively identify deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) as the "transforming principle" responsible for the transmission of genetic information. In 1953, Francis Crick and James Watson published their famous work on the structure of DNA, based on the research of Rosalind Franklin and Maurice Wilkins. These advances ushered in the era of molecular biology and led to the interpretation of evolution as a molecular process.[citation needed]

In the mid-1970s, Motoo Kimura formulated the neutralist theory of molecular evolution, firmly establishing the importance of genetic drift as the primary mechanism of evolution. To date, debates continue in this area of research. One of the most important is about the theory of punctuated equilibrium, a theory proposed by Niles Eldredge and Stephen Jay Gould to explain the paucity of transitional forms between species.

Darwinism

This stage of evolutionary thought began with the publication in August 1858 of a joint work by Darwin and Wallace, which was followed in 1859 by Darwin's book The Origin of Species, in the one that designates the principle of natural selection as the main engine of the evolutionary process and accepts the Lamarckian thesis of the inheritance of acquired characters as a source of biological variability; For this reason, although Wallace rejected Lamarckism, the name "Lamarck-Darwin-Wallace" is accepted to refer to this stage.

Darwin used the expression "descent with modification" instead of "evolution". Partly influenced by Thomas Malthus's Essay Concerning the Principle of Population (1798), Darwin noted that population growth would lead to a "struggle for existence" in which favorable variations prevailed while others perished. In each generation, many offspring fail to survive to breeding age due to limited resources. This could explain the diversity of plants and animals from a common ancestor through the operation of natural laws in the same way for all types of organisms.

The Origin of Species contained "a most ingenious theory to explain the appearance and perpetuation of varieties and specific forms on our planet" in the words of the prologue written by Charles Lyell (1797- 1895) and William Jackson Hooker (1785-1865). In fact, this work presented for the first time the hypothesis of natural selection. This hypothesis contained five fundamental statements:

- all organisms produce more offspring than the environment can sustain;

- There is abundant intraspecific variability for most characters;

- competition for limited resources leads to struggle "for life" (according to Darwin) or "for existence" (according to Wallace);

- decrease occurs with inheritable modifications

- and as a result, new species originate.

Darwin developed his theory of "natural selection" from 1838 and was writing his "great book" on the subject when Alfred Russel Wallace sent him a version of much the same theory in 1858. Their separate papers were presented together at an 1858 meeting of the Linnean Society in London. Lyell and Hooker credited Darwin as the first to formulate the ideas. presented in joint work, attaching as evidence an 1844 essay by Darwin and a letter he sent to Asa Gray in 1857, both published together with an article by Wallace. A detailed comparative analysis of Darwin's and Wallace's publications reveals that the latter's contributions were more important than is usually acknowledged, Thomas Henry Huxley applied Darwin's ideas to humans, using paleontology and comparative anatomy. to provide strong evidence that humans and apes shared a common ancestor.

Thirty years later, the co-discoverer of natural selection published a series of lectures under the title of "Darwinism" that deal with the same topics that Darwin had already dealt with, but in the light of facts and data that were unknown at the time of Darwin, who died in 1882. However, in his Origin of Species' , Darwin was the first to summarize a coherent set of observations that solidified the concept of evolution. of life in a true scientific theory ―that is, in a system of hypotheses―.

The list of Darwin's proposals presented in this work is shown below:

1. The supernatural acts of the Creator are incompatible with the empirical facts of nature.2. All life evolved from one or a few simple forms of organisms.

3. Species evolve from pre-existing varieties through natural selection.

4. The birth of a species is gradual and long lasting.

5. Upper taxons (geners, families, etc.) evolve through the same mechanisms as those responsible for the origin of species.

6. The greater the similarity between the taxa, the more closely related they are among themselves and the shorter the time of their divergence from the last common ancestor.

7. Extinction is mainly the result of interspecific competition.

8. The geological record is incomplete: the absence of forms of transition between species and higher-ranking taxa is due to gaps in current knowledge.

Darwin's great achievement was to show that it is possible to explain apparent teleology in non-teleological terms or ordinary causal terms. Life is not directional, it is not directed in advance.

Neo-Darwinism

Neo-Darwinism is a term coined in 1895 by the English naturalist and psychologist George John Romanes (1848-1894) in his work Darwin and after Darwin. The term describes a stage in the development of evolutionary theory that goes back to the German cytologist and zoologist August Weismann (1834-1914), who in 1892 provided experimental evidence against Lamarckian inheritance and postulated that the development of the organism does not influence hereditary material and that sexual reproduction in each generation introduces new variations in the population of individuals. Natural selection, then, can act on population variability and determine the course of evolutionary change. Neo-Darwinism enriched Darwin's original concept by emphasizing the origin of inter-individual variations and excluding Lamarckian inheritance as a viable explanation of the mechanism of heredity. Wallace, who popularized the term "Darwinism" in 1889, fully incorporated Weismann's new conclusions and was thus one of the earliest proponents of neo-Darwinism.

Modern evolutionary synthesis

This system of hypotheses of the evolutionary process originated between 1937 and 1950. In contrast to the neo-Darwinism of Weismann and Wallace, which gave primacy to natural selection and postulated Mendelian genetics as the mechanism for the transmission of traits between generations, the synthetic theory incorporated data from various fields of biology, such as molecular genetics, systematics and paleontology and introduced new mechanisms for evolution. For these reasons, these are different theories although the terms are sometimes used interchangeably.

According to the vast majority of historians of Biology, the basic concepts of the synthetic theory are essentially based on the content of six books, whose authors were: the Russian-American naturalist and geneticist Theodosius Dobzhansky (1900-1975); the German-American naturalist and taxonomist Ernst Mayr (1904-2005); British zoologist Julian Huxley (1887-1975); the American paleontologist George G. Simpson (1902-1984); the German zoologist Bernhard Rensch (1900-1990) and the American botanist George Ledyard Stebbins (1906-2000).

The terms «evolutionary synthesis» and «synthetic theory» were coined by Julian Huxley in his book Evolution: The Modern Synthesis (1942), in which he also introduced the term Evolutionary Biology instead of the phrase "study of evolution". In fact, Huxley was the first to point out that evolution "should be considered the most central and most important problem of biology and whose explanation should be approached through facts and methods from every branch of science, from ecology, genetics, paleontology, embryology, systematics to comparative anatomy and geographical distribution, without forgetting those of other disciplines such as geology, geography and mathematics".

The so-called "modern evolutionary synthesis" is a robust theory that currently provides explanations and mathematical models of the general mechanisms of evolution or evolutionary phenomena, such as adaptation or speciation. Like any scientific theory, its hypotheses are subject to constant criticism and experimental verification.[citation needed]

- The entities where evolution acts are the populations of organisms and not individuals. Theodosius Dobzhansky, one of the founders of modern synthesis, expressed the evolution as follows: "Evolution is a change in the genetic composition of populations. The study of evolutionary mechanisms corresponds to population genetics." This idea led to the "biological concept of species" developed by Mayr in 1942: a community of populations interspersed and reproductively isolated from other communities.

- Phenotypic and genetic variability in plant and animal populations is produced by genetic recombination—reorganization of chromosome segments during sexual reproduction—and random mutations. The amount of genetic variation that a population of organisms with sexual reproduction can produce is enormous. Consider the possibility of a single individual with a "N" number of genes, each with only two alleles. This individual can produce 2N sperm or genetically different eggs. Because sexual reproduction involves two parents, each descendant can, therefore, own one of the 4N different combinations of genotypes. Thus, if each parent has 150 genes with two alleles each—a human genome underestimation—each parent can give rise to more than 1045 genetically different gametes and more than 1090 genetically different descendants.[chuckles]required]

- Natural selection is the most important force modeling the course of phenotypic evolution. In changing environments, the directional selection is of particular importance, because it produces a change in the average population towards a new phenotype that best adapts to altered environmental conditions. In addition, in small populations, random gene derivation—the loss of genes from genetic acquis—can be significant.[chuckles]required]

- Speciation can be defined as “a step in the evolutionary process (in which) the forms... become incapable of hybridizing”. Various mechanisms of reproductive isolation have been discovered and studied in depth. It is believed that the geographical isolation of the founding population is responsible for the origin of new species in the islands and other isolated habitats and it is likely that the alopatric spice—the divergent evolution of populations that are geographically isolated from each other—is the predominant spice mechanism in the origin of many animal species. However, simpatric spice—the emergence of new species without geographical isolation—is also documented in many taxa, especially in vascular plants, insects, fish and birds.

- Evolutionary transitions in these populations are usually gradual, i.e. new species evolve from pre-existing varieties through slow processes and at each stage their specific adaptation is maintained.[chuckles]required]

- Macroevolution—phylogenetic evolution above the species level or the appearance of higher taxa—is a gradual, step-by-step process, which is only the extrapolation of microevolution—the origin of races and varieties, and of species—.[chuckles]required]

Punctuated balance

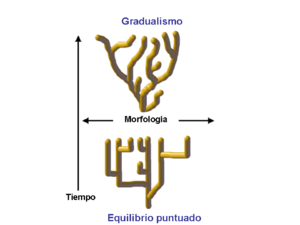

In evolutionary biology, the theory of punctured balance, also called interrupted balance, is a theory that proposes that once a species appears in the fossil record, the population stabilizes, showing few evolutionary changes during most of its geological history. This minimal or no morphological state of change is called stasis. According to theory, significant evolutionary changes are rare and geologically rapid events of branched spice called cladogenesis. Cladogenesis is the process by which a species is divided into two different species, rather than gradually transformed into another.

The punctured balance is commonly contrasted with philtic gradualism, the idea that evolution usually occurs uniformly and by the constant and gradual transformation of full lineages (called anagenesis). From this point of view, evolution is generally considered gradual and continuous.

In 1972, the paleontologists Niles Eldredge and Stephen Jay Gould developed this theory in a historic article entitled “Punctuated equilibria: an alternative to phyletic gradualism” (“Putted balances: an alternative to philtic gradualism”). The article was based on the model of geographical spice of Ernst Mayr, the theories of genetic homeostasis and the development of Michael Lerner, and his own empirical research. Eldredge and Gould proposed that the degree of gradualism commonly attributed to Charles Darwin is virtually nonexistent in the fossil record, and that stasis dominates the history of most fossil species. Elisabeth Vrba's change pulse hypothesis supports Eldredge and Gould's theory.Neutralist theory of molecular evolution

The neutralist theory of molecular evolution states that the vast majority of evolutionary changes at the molecular level are caused by the genetic drift of neutral mutants in terms of natural selection. The theory was proposed by Moto Kimura in 1968 and described in detail in 1983 in his book The Neutral Theory of Molecular Evolution, and although it was received by some as an argument against Darwin's theory of evolution through natural selection, Kimura maintained (with the agreement of the majority of those who work in evolutionary biology) that the two theories are compatible: "The theory does not deny the role of natural selection in the determination of the course of adaptive evolution". In any case, the theory attributes a great role to genetic drift.

Evolutionary Developmental Biology

Evolutionary Biology of Development (or Informally evo-devoEnglish evolutionary developmental biology) is a field of biology that compares the development process of different organisms in order to determine their phylogenetic relationships. Likewise, evo-devo, seeks to identify the mechanisms of development that give rise to evolutionary changes in the phenotypes of individuals (Hall, 2003). The main interest of this new evolutionary approach is to understand how the organic form (new structures and new morphological patterns) evolves. Thus, evolution is defined as the change in development processes.

The approach adopted by evo-devo is multidisciplinary, confluing disciplines such as the biology of development (including development genetics), evolutionary genetics, systematic, morphology, comparative anatomy, paleontology and ecology.Modern evolutionary synthesis

In Darwin's day, scientists did not know how traits were inherited. Subsequently, most hereditary characteristics were discovered to be related to persistent entities called genes, fragments of the linear deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) molecules in the nucleus of cells. DNA varies among members of the same species and also undergoes changes, mutations, or rearrangements due to genetic recombination.

Variability

The phenotype of an individual organism is the result of its genotype and the influence of the environment in which it lives and has lived. A substantial part of the variation between phenotypes within a population is caused by differences between its genotypes. The modern evolutionary synthesis defines evolution as the change in that genetic variation over time. The frequency of each allele fluctuates, being more or less prevalent in relation to other alternative forms of the same gene. Evolutionary forces act by directing these changes in allele frequencies in one direction or another. Variation in a population for a given gene disappears when there is fixation of an allele that has entirely replaced all other alternative forms of that same gene.

Variability arises in natural populations by mutations in genetic material, migrations between populations (gene flow), and by reorganization of genes through sexual reproduction. Variability can also come from the exchange of genes between different species, for example through horizontal gene transfer in bacteria or interspecific hybridization in plants. Despite the constant introduction of new variants through these processes, most of the genome of a species is identical in all individuals belonging to it. However, even small changes in the genotype can lead to substantial changes in the phenotype. Thus, chimpanzees and humans, for example, only differ in about 5% of their genomes.

Mutation

Darwin did not know the source of the variations in individual organisms, but he noted that they seemed to occur randomly. In later works, most of these variations were attributed to mutations. A mutation is a permanent, transmissible change in the genetic material—usually DNA or RNA—of a cell, produced by "miscopying" in the genetic material during cell division or by exposure to radiation, chemicals, or radiation. virus action. Random mutations constantly occur in the genome of all organisms, creating new genetic variability. Mutations may have no effect on the organism's phenotype, or may be deleterious or beneficial. By way of example, studies carried out on the fruit fly (Drosophila melanogaster) suggest that if a mutation determines a change in the protein produced by a gene, that change will be harmful in 70 % of cases and neutral or slightly beneficial in the rest.

The frequency of new mutations in a gene or DNA sequence in each generation is called the mutation rate. In scenarios of rapid environmental change, a high mutation rate increases the probability that some individuals have a suitable genetic variant to adapt and survive; on the other hand, it also increases the number of harmful or deleterious mutations that decrease the adaptation of individuals and raises the probability of extinction of the species. Due to the conflicting effects that mutations can have on organisms, the mutation rate optimal for a population is a trade-off between costs and benefits, which depends on the species and reflects evolutionary history in response to challenges imposed by the environment. Viruses, for example, have a high mutation rate, which It has an adaptive advantage since they must constantly and rapidly evolve to overcome the immune systems of the organisms they affect.

Gene duplication introduces extra copies of a gene into the genome, thereby providing the building blocks for the new copies to start their own evolutionary path. If the initial gene continues to function normally, its copies they can acquire new mutations without harm to the organism that hosts them and eventually adopt new functions. For example, in humans four genes are necessary to build the structures necessary to detect light: three for the vision of colors and one for night vision. All four genes have evolved from a single ancestral gene by duplication and subsequent divergence. Other types of mutation can occasionally create new genes from so-called non-coding DNA. New genes with different functions can also arise from fragments. of duplicated genes that recombine to form new DNA sequences.

Chromosomal mutations—also called chromosomal aberrations—are an additional source of heritable variability. Thus, translocations, inversions, deletions, Robertsonian translocations, and duplications usually cause phenotypic variants that are transmitted to offspring. For example, in the genus Homo a chromosome fusion took place that gave rise to chromosome 2 in humans, while other apes retain 24 pairs of chromosomes. Despite the phenotypic consequences that such chromosomal mutations, its greatest evolutionary importance lies in accelerating the divergence of populations that have different chromosomal configurations: the gene flow between them is severely reduced due to the sterility or semi-sterility of heterozygous individuals. In this way, chromosomal mutations act as reproductive isolation mechanisms that lead different populations to maintain their identity as species over time.

Fragments of DNA that can change position on chromosomes, such as transposons, make up a major fraction of the genetic material of plants and animals and may have played a prominent role in their evolution. By inserting into or cleaving from In other parts of the genome these sequences can activate, inhibit, delete or mutate other genes and thus create new genetic variability. Also, some of these sequences are repeated thousands or millions of times in the genome and many of them have adopted functions important, such as the regulation of gene expression.

Genetic recombination

Genetic recombination is the process by which genetic information is redistributed by transposition of DNA fragments between two chromosomes during meiosis ―and more rarely in mitosis―. The effects are similar to those of mutations, that is, if the changes are not deleterious, they are transmitted to the offspring and contribute to increasing the diversity within each species.[citation required]< /sup>

In asexual organisms, genes are inherited together, or linked, since they do not mix with those of other organisms during the recombination cycles that usually occur during sexual reproduction. In contrast, the offspring of sexually reproducing organisms contain a random shuffling of their parent's chromosomes, which is produced during meiotic recombination and subsequent fertilization. Recombination does not alter allele frequencies but modifies the existing association between alleles belonging to different genes, producing offspring with unique combinations of genes. Recombination generally increases genetic variability and may also increase rates of evolution. However, the existence of asexual reproduction, such as occurs in apomictic plants or in parthenogenetic animals, indicates that this mode of reproduction may also be advantageous in certain environments. Jens Christian Clausen was one of the first to formally recognize that apomixis, particularly facultative apomixis, does not necessarily lead to a loss of genetic variability and evolutionary potential. Using an analogy between the adaptive process and the large-scale production of automobiles, Clausen argued that the combination of sexuality (which allows the production of new genotypes) and apomixis (which allows unlimited production of the most adapted genotypes) enhances the ability of a species for adaptive change.

Although the recombination process makes it possible for genes grouped on a chromosome to be inherited independently, the recombination rate is low ―approximately two events per chromosome and per generation―. As a result, adjacent genes tend to be inherited together, in a phenomenon called linkage. A group of alleles that are usually inherited together because they are linked is called a haplotype. When one of the alleles in the haplotype is highly beneficial, natural selection can lead to a selective sweep that increases the proportion within the population of the rest of the alleles in the haplotype; this effect is called the "hitchhiking" effect.

When alleles do not recombine, as is the case on the Y chromosome in mammals or asexual organisms, genes with deleterious mutations accumulate, known as the Muller ratchet. i> in English). Thus, by breaking down linked gene pools, sexual reproduction facilitates the elimination of deleterious mutations and the retention of beneficial ones, as well as the emergence of individuals with new and favorable genetic combinations. These benefits must outweigh other detrimental effects of sexual reproduction, such as the lower reproductive rate of populations of sexual organisms and the separation of favorable combinations of genes. In all sexual species, and with the exception of hermaphroditic organisms, each population is made up of individuals of two sexes, of which only one is capable of producing offspring. In an asexual species, on the other hand, all members of the population have this capacity, which implies a faster growth of the asexual population in each generation. Another cost of sex is that males and females must find each other to mate, and sexual selection often favors traits that reduce the fitness of individuals. This cost of sex was first expressed in mathematical terms by John Maynard Smith. The reasons for the evolution of sexual reproduction are still unclear and it is a question that is an active area of research in evolutionary biology, which has inspired ideas such as the Red Queen hypothesis. Science writer Matt Ridley, who popularized the term in his book The Red Queen: Sex and the Evolution of Human Nature, argues that there is a race cyclical arms player between organisms and their parasites and speculates that sex serves to preserve genes that are circumstantially unfavorable, but potentially beneficial in the face of future changes in parasite populations.[citation needed]

Population genetics

As previously described, from a genetic point of view, evolution is an intergenerational change in the frequency of alleles within a population that shares the same genetic heritage. A population is a group of individuals of the same species. that share a geographic area. For example, all the moths of the same species that live in an isolated forest form a population. A given gene within the population can present various alternative forms, which are responsible for the variation between the different phenotypes of organisms. An example might be a coloration gene in moths that has two alleles: one for white and one for black. The heritage or gene pool is the complete set of alleles in a population, such that each allele appears a certain number of times in a gene pool. The fraction of genes in the genetic heritage that are represented by a given allele is called the allele frequency, for example, the fraction of moths in the population that have the allele for black color. Evolution occurs when there are changes in allele frequency in a population of interbreeding organisms, for example if the allele for black color becomes more common in a population of moths.

To understand the mechanisms that cause a population to evolve, it is helpful to know the conditions necessary for the population not to evolve. The Hardy-Weinberg principle states that the frequency of alleles in a sufficiently large population will remain constant only if the only force at work is random recombination of alleles during gamete formation and subsequent combining of alleles during fertilization. In this case, the population is in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium and therefore does not evolve.

Gene flow

Gene flow is the exchange of genes between populations, usually of the same species. Examples of gene flow include the interbreeding of individuals after the immigration of one population into the territory of another, or, in the case of plants, the exchange of pollen between different populations. Gene transfer between species involves the formation of hybrids or horizontal gene transfer.

The immigration and emigration of individuals in natural populations can cause changes in allelic frequencies, as well as the introduction ―or disappearance― of allelic variants within an already established gene pool. Physical separations in time, space, or specific ecological niches that may exist between natural populations restrict or disable gene flow. In addition to these restrictions on the exchange of genes between populations, there are other mechanisms of reproductive isolation made up of characteristics, behaviors, and physiological processes that prevent members of two different species from interbreeding or mating with each other, producing offspring, or preventing them from being viable or fertile. These barriers constitute an essential phase in the formation of new species since they maintain their own characteristics over time by restricting or eliminating gene flow between individuals of different populations.

Different species can be interfertile, depending on how far they have diverged from their common ancestor; for example, the mare and donkey can mate and produce the mule. Such hybrids are generally sterile due to chromosomal differences between the parent species, which prevent the correct pairing of chromosomes during meiosis. In this case, closely related species can regularly interbreed, but natural selection works against hybrids. However, from time to time, viable and fertile hybrids are formed that may have intermediate properties between their parent species or possess an entirely new phenotype.

The importance of hybridization in the creation of new species of animals is not clear, although there are well-documented examples such as the frog Hyla versicolor. Hybridization is, however, a important mechanism of formation of new species in plants, since they tolerate polyploidy - the duplication of all the chromosomes of an organism - more easily than animals; polyploidy restores fertility in interspecific hybrids because each chromosome it is capable of mating with an identical partner during meiosis.

There are two basic mechanisms of evolutionary change: natural selection and genetic drift. Natural selection favors genes that improve the organism's ability to survive and reproduce. Genetic drift is the change in the frequency of alleles, caused by the random transmission of genes from one generation to the next. The relative importance of natural selection and genetic drift in a population varies depending on the strength of selection and the effective population size, which is the number of individuals in that population capable of reproducing. Natural selection usually dominates in large populations, while genetic drift predominates in small ones. The prevalence of genetic drift in small populations can even lead to the fixation of slightly deleterious mutations. As a result, changes in the size of a population can significantly influence the course of evolution. The so-called «bottlenecks», or temporary drastic decreases in the effective size of the population, suppose a loss or erosion of genetic variability and lead to the formation of genetically more uniform populations. Bottlenecks can be the result of catastrophes, variations in the environment, or alterations in gene flow caused by reduced migration, expansion into new habitats, or population subdivision.

Natural selection

Natural selection is the process by which genetic mutations that enhance reproductive capacity become, and remain, increasingly frequent in successive generations of a population. It is often called a "self-evident mechanism" because it is the necessary consequence of three simple facts: (a) within populations of organisms there is heritable variation (b) organisms produce more offspring than can survive, and (c)) such offspring have different abilities to survive and reproduce.

The central concept of natural selection is the biological fitness of an organism. Fitness, fit, or fitness influences the extent of an organism's genetic contribution to the next generation. Fitness, however, is not simply equal to the total number of offspring of a given organism, as it also quantifies the proportion of subsequent generations that carry that organism's genes. For example, if an organism can survive and reproduce, but its offspring are too small or unhealthy to reaching reproductive age, the genetic contribution of that organism to future generations will be very low and, therefore, its fitness is also very low.

Therefore, if one allele increases fitness more than others, with each generation the allele will become more common within the population. Such traits are said to be "favourably selected." An improvement in survival or increased fecundity are examples of traits that can increase fitness. Conversely, lower fitness caused by a less beneficial or deleterious allele causes it to become increasingly rare in the population and suffer "negative selection". It should be stressed that the fitness of an allele is not a fixed characteristic: if as the environment changes, traits that were previously neutral or harmful may become beneficial, and vice versa. another dark called carbonaria form. The typica form, as its name indicates, is the most frequent in this species. However, during the industrial revolution in the UK the trunks of many trees on which the moths roosted were blackened by soot, giving the dark-coloured moths a better chance of surviving and producing more offspring by spending more time easily unnoticed by predators. Just fifty years after the first melanic moth was discovered, almost all of the moths in the Manchester industrial area were dark. This process was reversed by the "Clean Air Act" of 1956, which reduced industrial pollution. As the color of the trunks lightened, the dark moths again became more easily visible to predators and their numbers decreased. However, even if the direction of selection changes, traits that would have been lost in the past cannot be restored. obtained in an identical way ―a situation described by Dollo's Law or "Law of evolutionary irreversibility"―. According to this hypothesis, a structure or organ that has been lost or discarded during the course of evolution will not appear again in the future. that same lineage of organisms.

According to Richard Dawkins, this hypothesis is "a statement about the statistical improbability of following exactly the same evolutionary trajectory twice, or indeed the same particular trajectory in both directions".

Within a population, natural selection for a certain continuously varying trait, such as height, can be categorized into three different types. The first is "directional selection," which is a change in the mean value of a trait over time; for example, when organisms grow taller. Second is "disruptive selection" which is the selection for extreme values of a certain trait, often resulting in extreme values being more common and the selection works against the average value; this implies, in the example above, that short and tall organisms have an advantage, but those of medium height do not. Finally, in the "stabilizing selection", the selection acts against the extreme values, which determines a decrease in the variance around the average and a lower variability of the population for that particular character; selection, all organisms in a population would gradually acquire a similar height.[citation needed]

A special type of natural selection is sexual selection, which acts in favor of any trait that increases reproductive success by increasing an organism's attractiveness to potential mates. Certain traits acquired by males through sexual selection—such such as bulky horns, mating songs, or bright colors—can reduce the chances of survival, for example by attracting predators. However, this reproductive disadvantage is offset by greater reproductive success for males exhibiting these traits.

An active study area is the so-called «selection unit»; natural selection has been said to act at the level of genes, cells, individual organisms, groups of organisms, and even species. None of these models is mutually exclusive, and selection can act at multiple levels at once. For example, below the level of the individual, there are genes called transposons that attempt to replicate throughout the genome. Selection above the level of the individual, such as group selection, may allow the evolution of cooperation.

Genetic drift

Genetic drift is the change in the frequency of alleles between one generation and the next, and it occurs because the alleles of the offspring are a random sample of the parents, and because of the role that chance plays in timing. to determine if a given individual will survive and reproduce. In mathematical terms, alleles are subject to sampling error. As a result, when selective forces are absent or relatively weak, allele frequencies tend to "drift" up or down randomly (in a random walk). This drift stops when an allele finally becomes fixed, that is, it either disappears from the population or completely replaces the rest of the genes. Thus, genetic drift can eliminate some alleles from a population simply due to chance. Even in the absence of selective forces, genetic drift can cause two separate populations that start out with the same genetic makeup to split into two divergent populations with a different set of alleles.

The time required for an allele to become fixed by genetic drift depends on the size of the population; fixation occurs faster in smaller populations. The precise measurement of populations that is important in this case is called the effective population size, which was defined by Sewall Wright as the theoretical number of breeding individuals of the same degree. consanguinity observed.

Although natural selection is responsible for adaptation, the relative importance of the two forces, natural selection and genetic drift, as drivers of evolutionary change in general is currently a field of research in evolutionary biology. These investigations were inspired by by the neutralist theory of molecular evolution, which postulates that most evolutionary changes result from the fixation of neutral mutations, which have no immediate effect on an organism's fitness. Thus, in this model, most of genetic changes in a population are the result of constant mutation pressure and genetic drift.

The consequences of evolution

Adaptation

Adaptation is the process by which a population becomes more adapted to its habitat and also the change in the structure or function of an organism that makes it more adapted to its environment. This process occurs by selection natural for many generations and is one of the basic phenomena of biology.

The importance of an adaptation can only be understood in relation to the total biology of the species. Julian Huxley

Species tend to adapt to different ecological niches to minimize competition between them. This is known as the principle of competitive exclusion in ecology: two species cannot occupy the same niche in the same environment for a long time.

Adaptation does not necessarily imply major changes in a physical part of a body. As an example, we can mention the flukes ―internal parasites with very simple body structures, but with a very complex life cycle― in which their adaptations to such an unusual environment are not the product of characters observable with the naked eye but in critical aspects. of their life cycle. In general, the concept of adaptation includes, in addition to the adaptive process itself, all aspects of the organisms, populations or species that are its result. By using the term «adaptation» for the evolutionary process and “adaptive trait or character” for its product, the two senses of the concept are perfectly distinguished. According to Theodosius Dobzhansky, "adaptation" is the evolutionary process by which an organism becomes more capable of living in its habitat or habitats, while "adaptability" is the state of being adapted, that is, the degree to which an organism organism is capable of living and reproducing in a given set of habitats. Finally, an "adaptive trait" is one of the aspects of an organism's development that increases its likelihood of surviving and reproducing.

Adaptation sometimes involves gaining a new feature; notable examples are the laboratory evolution of Escherichia coli bacteria so that they may be able to use citric acid as a nutrient, when wild-type bacteria cannot; the evolution of a new enzyme in Flavobacterium that allows these bacteria to grow on the by-products of nylon manufacturing; and the evolution of an entirely new metabolic pathway in the soil bacterium Sphingobium which allows it to break down the synthetic pesticide pentachlorophenol. Sometimes, loss of an ancestral function can also occur. An example that shows both types of change is the adaptation of the bacterium Pseudomonas aeruginosa to fluoroquinolone with genetic changes that modify the molecule on which it acts and by increasing the activity of the transporters that pump the antibiotic outside the cell. An idea that is still controversial is that some adaptations can increase the ability of organisms to generate genetic diversity and to adapt by natural selection ―in other words, they would increase the ability to evolve―.

A consequence of adaptation is the existence of structures with similar internal organization and different functions in related organisms. This is the result of modifying an ancestral structure to adapt it to different environments and ecological niches. The wing bones of bats, for example, are very similar to those of mouse feet and primate hand bones, because all of these structures were present in a common mammalian ancestor. all living organisms are related to some degree, even structures that differ profoundly, such as the eyes of arthropods, squid, and vertebrates, or the limbs and wings of arthropods and vertebrates, depend on a common set of genes homologs that control their development and function, called deep homology.

During adaptation, vestigial structures may appear, lacking functionality in a species; however, the same structure is functional in the ancestral species or in other related species. Examples include pseudogenes, the eyes of blind cave fish, wings in flightless bird species, and the hip bones present in whales and snakes. Examples also exist in humans. of vestigial structures, such as wisdom teeth, tailbone, vermiform appendix, and involuntary reactions such as goosebumps and other primitive reflexes.

Some features that appear to be simple adaptations are, in fact, exaptations: structures originally adapted for one function, but coincidentally made useful for another purpose. An example is the African lizard Holaspis guentheri which developed a very flattened head and trunk to hide in crevices, as can be seen in other lizards of the same genus. However, in this species, the flattened body allows it to glide from tree to tree. The lungs of ancestral lungfishes are an exaptation of the swim bladders of teleost fish used as a buoyancy regulator.

A branch of evolutionary biology studies the development of adaptations and exaptations. This area of research addresses the origin and evolution of embryonic development and how new features arise from developmental modifications. These studies have shown, for example, that the same bone structures in embryos that are part of the jawbone in some animals are instead part of the middle ear in mammals. Changes in genes that control development can also cause lost structures to reappear during evolution, such as the teeth of mutant chicken embryos, similar to those of crocodiles. In fact, it is becoming increasingly clear that most alterations in the shape of organisms are due to changes in a small set of conserved genes.

Coevolution

The interaction between organisms can produce conflict or cooperation. When two different species interact, such as a pathogen and a host, or a predator and its prey, the evolution of one causes adaptations in the other; these changes in the second species cause, in turn, new adaptations in the first. This cycle of selection and response is called coevolution. An example is the production of tetrodotoxin by the Oregon newt and the evolution of resistance to this toxin in its predator, the garter snake. In this predator-prey pairing, the evolutionary arms race (Red Queen Hypothesis) has resulted in increased toxin production in the newt, and a corresponding increase in resistance to it in the snake. An example of coevolution that did not involves competition (Red King Hypothesis) are symbiotic and mutualistic interactions between mycorrhizae and plant roots or bees and the plants they pollinate. Another example of an entity that coevolves with its host is viruses with cells. Cells usually develop defenses in their immune system to avoid viral infections, however viruses must mutate quickly in order to avoid these cellular defenses or the host's immune system. Therefore, viruses are the only entities that evolve faster than any other for their existence. Viruses are entities that can only evolve and survive in cells. According to recent studies, they have been coevolving with cells since their origins (protobiont) and therefore their origin is prior to that of the last universal common ancestor. Viruses could have arisen in these protobionts or before, to later serve as a means of horizontal gene transfer (mobile genetic element) and regulate the population of certain cellular organisms. In fact, new types of viruses could also have emerged during different stages of evolution, through various molecular mechanisms such as recombinations between mobile genetic elements with other viruses. They can even jump between various cellular organisms and acquire new hosts.

Speciation

Speciation (or cladogenesis) is the process by which a species diverges into two or more descendant species. Evolutionary biologists view species as statistical phenomena and not as categories or types. This approach is contrary to the still deeply rooted classical concept of a species as a class of organisms exemplified by a "type specimen" that possesses all the characteristics common to that species. Instead, a species is now thought of as a lineage that shares a single gene pool and evolves independently. According to this description, the boundaries between species are blurred, although both genetic and morphological properties are used to help differentiate between closely related lineages. In fact, the exact definition of the term "species" is still under debate, particularly for organisms based on prokaryotic cells; it is what is called the "species problem". Various authors have proposed a series of definitions based on different criteria, but the application of one or the other is finally a practical matter, depending on each case. of the particularities of the group of organisms under study. Currently, the main unit of analysis in biology is the population, an observable set of interacting individuals, rather than the species, an observable set of individuals that resemble each other.[citation needed]

Speciation has been observed on multiple occasions both under controlled laboratory conditions and in nature. In sexually reproducing organisms, speciation is the result of reproductive isolation followed by genealogical divergence. There are four modalities of speciation. The most common in animals is allopatric speciation, which takes place in populations that remain geographically isolated, as in the case of habitat fragmentation or migrations. Under these conditions, selection can cause very rapid changes in the appearance and behavior of organisms. Due to the processes of selection and genetic drift, the separation of populations can result in offspring that cannot reproduce between them.

The second modality of speciation is peripatric speciation, which occurs when small populations become isolated in a new environment. It differs from allopatric speciation in that the isolated populations are numerically much smaller than the parent population. This causes rapid speciation by accelerating genetic drift and selection on a small gene pool, a process known as the founder effect.

The third modality of speciation is parapatric speciation. It is similar to peripatric speciation in that a small population colonizes a new habitat, but differs in that there is no physical separation between the two populations. Instead, speciation is the result of the evolution of mechanisms that reduce gene flow between the two populations. Generally, this occurs when there has been a drastic change in the environment within the habitat of the parent species. An example is the grass Anthoxanthum odoratum, which can undergo parapatric speciation in response to localized metal contamination from mines. In this case, plants evolve with a resistance to high levels of metals in the soil; Reproductive isolation occurs because selection favors a flowering season different from that of the parent species for the new plants, which cannot then lose the genes that give them resistance through hybridization. Selection against hybrids can be enhanced by differentiation of traits that promote reproduction between members of the same species, as well as by increasing differences in appearance in the geographic area in which they overlap.

Finally, in sympatric speciation, species diverge without geographic isolation or habitat change. This pattern is rare, as even a small amount of gene flow can eliminate genetic differences between parts of a population. In general, in animals, sympatric speciation requires the evolution of genetic differences and non-random mating, for it to occur. may develop reproductive isolation.

One type of sympatric speciation is the crossing of two related species to produce a new hybrid species. This is unusual in animals, because homologous chromosomes from parents of different species cannot successfully pair during meiosis. It is most common in plants, which often double their chromosome number to form polyploids. This allows the chromosomes from each parent species to form a complementary pair during meiosis, since each parent's chromosomes are already represented by one pair. An example of this type of speciation occurred when the plant species Arabidopsis thaliana and Arabidopsis arenosa interbred to produce the new species Arabidopsis suecica. This took place approximately 20,000 years ago, and the speciation process has been reproduced in the laboratory, which has made it possible to study the genetic mechanisms involved in this process. In fact, the duplication of chromosomes within a species can be a common cause of reproductive isolation, as half of the duplicated chromosomes will be unpaired when they mate with those of unduplicated organisms.