Bike bark

Ladri di biciclette (in Latin America, Bicycle thieves; in Spain and Chile, Bicycle Thief) is a 1948 Italian drama film directed by Vittorio de Sica. It is considered one of the emblematic films of Italian neorealism. In 1954, Sight and Sound magazine published its first list of the "Ten Greatest Films Ever Made," Ladri di biciclette was at the top of that list. list. In 1962 it was placed seventh on the same list. It occupies one of the first ten positions on the list of "The 50 Movies You Should See at 14".

The film is based on the homonymous novel written by Luigi Bartolini in 1945 and adapted for the big screen by Cesare Zavattini. The story narrates an accident in the daily life of a worker. This accident consists of the theft of the bicycle with which he goes to work. This act would be banal if the context of the 1948 Italian society in which the film is set is not taken into account. The choice of the bicycle as the key object of the drama is characteristic of Italian urban customs, and at the same time, of a time when mechanical means of transport are still scarce and expensive.

Plot

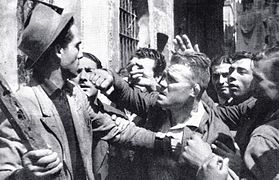

Post-War II Rome: Antonio Ricci (Lamberto Maggiorani), an unemployed man finds work pasting posters, which is a great achievement in the post-war situation in the country, where work is scarce and obtaining it is an exceptional success. But to work he must own a bicycle. Unfortunately, on the first day of work, his bike is stolen while he is pasting up a movie poster. Antonio chases the thief to no avail. He decides to report the theft to the police, but realizes that law enforcement cannot help him find his bike. Desperate, he seeks the support of a fellow party member, who in turn mobilizes his garbage collector friends. At dawn, Antonio, together with his companions and his son Bruno, begins his search, first in Piazza Vittorio and later in Porta Portese, where stolen objects traditionally end up. But there is nothing to do: the bike is probably already disassembled and will be impossible to find. At Porta Portese, Antonio sees the thief of his bicycle, while he is negotiating with an old bum. He chases after him without catching up, returns to Porta Portese to find the homeless man, and follows him to a soup kitchen. There he asks about his bike and the identity of the thief, but gets no results. Exasperated, Antonio goes to a psychic, but her answer is almost a joke: "either you find her now or you will never find her". Immediately, upon leaving the psychic's house, he meets the thief of the bicycle who is ultimately defended by all of his colleagues. Antonio talks to a policeman to explain the situation. Then he answers that without witnesses to the robbery nothing can be done. Finally, while Antonio and Bruno wait for the bus to return home, the father notices the existence of a bicycle that no one seems to be guarding. He tries to steal it but the crowd rushes to catch him. Only Bruno's cries manage to stop them and prevent his father from going to jail. Antonio is now as poor as before but with the shame of having placed himself at the level of the person who had stolen from him. The film closes with Antonio and Bruno returning home as night falls over the city of Rome.

Cast

- Lamberto Maggiorani - Antonio Ricci

- Enzo Staiola - Bruno Ricci, son of Antonio

- Lianella Carell - Maria Ricci, wife of Antonio

- Gino Saltamerenda - Baiocco, friend of Antonio

- Vittorio Antonucci - Rafael Catelli, the thief

- Giulio Chiari - Mendigo

- Elena Altieri - The Lady of Charity

- Carlo Jachino - Mendigo

- Michele Sakara - The Secretary of the Organization of Charity

Comment

A characteristic feature of this film, and of neorealism, is the disappearance of the notion of actor and mise-en-scène. The actors involved are not professionals. Although the search for the people who would play the characters was tough. One detail of the search for the child was that De Sica, after having seen a number of children, opted for one due to his gait. What's more, the children's selection test was reduced to seeing them walk. In addition, no scenes were made in studios, but all were shot on the street.

Another significant feature is that all the camera angles depend on what you want to transmit. For example, the sequence in which the entire street can be seen with a dive, showing us the crowd among which the thief is lost and the impotence of the worker.

The film's thesis is superbly and tremendously simple, and is eclipsed behind a social reality that in turn takes the background of the moral and psychological drama that would be enough to justify the film:

"In the world in which this worker lives, the poor, to subsist, must be robbed among them. »André Bazin, Neorealism.

Critical reception

When the film was released in Italy, it was met with hostility as it portrayed Italians in a negative light. The Italian critic Guido Aristarco praised it, but also complained that "sentimentality can sometimes take the place of artistic emotion." Italian neorealist film director Luchino Visconti criticized the film, saying it was a mistake to use a professional actor to dub over Lamberto Maggiorani's dialogue. Luigi Bartolini, the author of the novel from which Sica got her title, was highly critical of the film, feeling that the spirit of his book had been completely betrayed, as its protagonist was a middle-class intellectual and its subject was breakdown of civil order in the face of anarchic communism.

Bike Thieves has received critical acclaim since its release, with movie review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes reporting 98% of reviews positive out of 54 with an average of 9.1 out of 10. The picture is also on the List of Best Vatican Films to Portray Humanistic Values.

The New York Times film critic Bosley Crowther praised the film and its message in his review. He wrote: 'Once again the Italians have sent us a brilliant and devastating film in Vittorio De Sica's pitiful drama of modern urban life. Fervently heralded by those who have seen it abroad (where it has already won several awards at various film festivals), this heartbreaking picture of frustration, which arrived [at the World Theater] yesterday, is going to fulfill all the forecasts of its absolute triumph. here. Once again, De Sica, who gave us the crushing Bitumen, that desperately tragic demonstration of youthful corruption in post-war Rome, has settled down and sharply captured in simple and realistic terms an important, indeed, fundamental and universally dramatic. It is the isolation and loneliness of the little man in this complex social world that is ironically blessed with institutions to comfort and protect humanity'. Pierre Leprohon wrote in Cinéma D'Aujourd that" what should not be ignored on the social level is that the character is not shown at the beginning of a crisis but in its outcome. It is enough to look at his face, his insecure look, his hesitant or fearful attitudes to understand that Ricci is already a victim, a diminished man who has lost his trust. . 4; Lotte Eisner called it the best Italian film since World War II and Robert Winnington called it "the most successful foreign film in British cinema".

When the film was re-released in the late 1990s, Bob Graham, film critic for the San Francisco Chronicle gave the drama a positive review: "The roles are played by non-actors, Lamberto Maggiorani as the father and Enzo Staiola as the solemn boy, who at times appears to be a miniature man. They lend great dignity to De Sica's unblinking vision of postwar Italy. The wheel of life turns and makes people grind, it is impossible to imagine this story in any other way than that of De Sica. The new black and white print has an extraordinary range of gray tones that get darker as life closes in.

Scene analysis

- At the scene of the restaurant, where there is a false alarm of the child's drowning makes the father understand the relative insignificance of his misfortune by creating a naturally fictitious kind of dramatic respite, since the reality of that happiness depends, finally, on finding the bike.

- In the development of the film there is a scene in which the protagonist comes to a Catholic working association from which he expects a help that he does not receive because he does not complain "syndically" but will find some friends to help him find his stolen object. It turns out that a meeting of unionized proletarians behaves in the same way as a group of paternalistic bourgeois in the sight of an unfortunate worker. The union's indifference is justified since the unions work for justice and not for charity; but the annoying paternalism of the Catholic opponents is intolerable, since their charity is not manifested in the face of this individual tragedy.

- Another scene in the film shows how a choir of Austrian seminarians surrounds the father and the son. It is one of the most expressive sequences in terms of what was said earlier, since it would be difficult to create a more anticlerical situation.

- The scene where Bruno's father decides to steal the bike is of great importance in the film because it symbolizes a key moment in the evolution of the child. The character assists the transformation suffered by his father, who becomes a hero to be a thief.

- One of the last scenes of the film represents the change of the father-son relationship: in this scene the final gesture of the child is misinterpreted who gives his father his hand again. The hand that slips in yours is neither the sign of a forgiveness nor a child comfort, but a serious gesture that puts both of them on an equal footing. Man until then was a god for his son, his relationship was produced under a sign of admiration.

"The tears that shed walking together, with the fallen arms, are of despair before the lost paradise. But the child returns the father through his failure; now he will want him like a man, with his shame. »André Bazin, Neorealism

Awards

| Publication | Country | Prize | Year | Post |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Empire | EUA | The Best Films of World Cinema | 2012 | 4 |

- Film Writer Circle Medal to the best foreign film.

- Oscar Awards: Honorary Prize. Voted by the Board of Governors of the Academy as the most outstanding non-English film launched in the United States during 1949; 1950.

- Golden Globes: Best Foreign Film, Italy; 1950.

- National Board of Review: NBR Award, Best Director, Sica Vittorio; Best Film (any language), Italy; 1949.

- New York Film Critics Circle Awards: Best Foreign Language Film; 1949.

- BAFTA Awards: Best Film of any Source; 1950.

- International Film Festival in Locarno Switzerland: Special Prize for the Vittorio De Sica jury; 1949.

Contenido relacionado

Music

Wedge Antilles

Ringu