Ben Hur (1959 film)

Ben-Hur is a 1959 American epic drama film set largely in the Roman province of Judea in the time of Emperor Tiberius. It was directed by William Wyler and produced by Sam Zimbalist for Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. His main roles are played by Charlton Heston, Stephen Boyd, Jack Hawkins, Hugh Griffith and Haya Harareet. As an adaptation of the 1925 silent film of the same title, Ben-Hur is based on the novel of the same name written by Lewis Wallace in 1880. The script is written by Karl Tunberg, although the booklet includes contributions by Maxwell Anderson, S.N. Behrman, Gore Vidal, and Christopher Fry.

Ben-Hur had the largest budget ever for a film, exceeding US$15 million. For its filming, two hundred artists and workers built the largest sets ever used in a film, with hundreds of friezes and statues, while costume designer Elizabeth Haffenden led a team of one hundred seamstresses. Filming began on May 18, 1958, and lasted until January 7, 1959, with shooting days of between twelve and fourteen hours that took place six days a week. Pre-production began at the Cinecittà studios in Rome in October 1957 and post-production lasted six months. MGM executives commissioned cinematographer Robert L. Surtees to shoot the film in widescreen format, which was not to Wyler's taste. More than 200 camels, 2,500 horses and some 10,000 extras were used in the filming. The sea battle was filmed with miniatures in a large water tank at the Metro studios in Culver City, California. The nine-minute chariot race is one of the most famous sequences in film history, while the soundtrack, composed and directed by Miklós Rózsa, is the longest ever created for a feature film. profoundly influenced cinema for more than fifteen years.

After spending $14.7 million promoting it, Ben-Hur opened at New York's Loew's Theater on November 18, 1959. It was the highest-grossing film of that year and it became the second most profitable film, only behind Gone with the Wind. The film garnered a record eleven Oscars, including Best Picture, Best Director (Wyler), Best Actor (Heston), Best Supporting Actor (Griffith) and Best Cinematography (Surtees), an achievement unmatched until the premiere of Titanic in 1997 and The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King in 2003. Ben-Hur also received three Golden Globe Awards — for Best Motion Picture Drama, Best Director, and Best Supporting Actor (Boyd). Currently, Ben-Hur is considered one of the best films in the history of cinema, which is why in 2004 the National Film Preservation Board selected it for be preserved in its National Film Registry for being a "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant" film.

Plot

The action takes place in Judea, during the year 30 AD. C. The Roman Empire, owner and lord of the known world, governs its vast territories with an iron fist, including Judea, harshly subduing its inhabitants. They look forward to the arrival of a new Messiah who will free the Jewish people from the Roman yoke. Among them is Judah Ben-Hur (Charlton Heston), a wealthy prince who trades spices from the Orient to Rome, a respected man who believes in the faith of his people and his God.

However, times are troubled and a violent uprising against Roman power is feared, to which the latter responds by sending two legions under the command of military chief Messala (Stephen Boyd), Ben's old childhood friend -hur. Judah Ben-Hur sees a friend in Messala and also a chance for change for his people, a hope for understanding and respect. But instead, Messala sees his old friend as the man who will "point out" Rome's Jewish enemies because of his past friendship. However, Ben-Hur refuses the deal and an enraged Messala breaks off the relationship.

Fearful of his former friend, Ben-Hur knows he's going to have to be careful going forward. However, a stroke of bad luck comes: his only sister, Tirzah, leans on the edge of the roof of her house and a tile falls off as the procession carrying the governor passes by, causing him to hit himself when he falls next to him. with his horse, and this incident, despite being accidental, causes his old friend to imprison him along with his mother and sister, accused of attacking the new governor of Judea, Valerio Grato. Judah tries to escape from prison, but not before talking to Messala, threatening him with a spear and persuading him to release his mother and sister, pleading innocence. After the failed assassination attempt against the tribune, Judah is sent to the port of Tire, without trial, as a galley slave on a galley. Ben-Hur swears revenge on Messala even if it takes a lifetime.

On his journey to the port, Judah meets Jesus of Nazareth, who will give him water. The face of the person who helped him will remain engraved in his memory, the same person who, with a firm look and full of peace, persuaded the threat of a Roman foreman towards him and Judah by giving him water, when minutes before the population had been prohibited from providing water only to him. After three years as a galley slave, Ben-Hur will meet Quintus Arius, Rome's first consul, whose life he saves during the sinking of the galley in a naval battle against the Macedonians. As gratitude to Judah, Quintus adopts him as his son, with which he obtains riches, championships as a charioteer in the Roman circus for five consecutive years, and titles. However, despite the riches, power and glory of Rome, Ben-Hur knows that he has an oath to fulfill and that he cannot wait any longer, even more so when Judah meets in one of the many meetings in the palace of his father to the next governor of Judea: Pontius Pilate. He asks his father to return to Judea and settle his family's affairs. Quinto knows that Judah is unlikely to return, so he agrees to his request, knowing that the father-son bond still existed. It's time for revenge.

On his way to Jerusalem, Ben-Hur meets Baltasar and Sheikh Ilderim, an Arab merchant famous for his avid betting on horse racing. From Baltasar he learns that there is someone to believe in, a Messiah, son of God, who will free men from their anger and hatred. On the contrary, the sheikh discovers that Messala participates in chariot races and in the circus arena, where death is not a crime.

Fueled by his hatred, Judah agrees to compete against Messala in the races and, on the other hand, searches for his mother and sister. Upon returning to Judea, he discovers that everything he had known has been reduced to ruins, that his family has disappeared and that the only explanation he has is from the daughter of one of his slaves, named Esther, whom Judah loved deeply, and his father, a faithful butler to the Ben-Hur family, who was tortured leaving him paralyzed.

After condemning Judah to the galleys, Messala had not only confiscated all of Ben-Hur's assets, but he had ruthlessly attacked his mother and sister, locking them in the deepest dungeons. With Judah's return and determined to appease his revenge, a tense Messala sends for Judah's family, in exchange for forgetting what happened eight years ago. To his surprise, so many years in a filthy cell in the remote dungeons have made them sick with leprosy. Once freed, mother and sister sneak back home to find ruin and poverty. Esther promises not to tell anyone about her future and painful final whereabouts: the Valley of the Lepers, not even her son Judah.

Esther immediately confesses to Judah that her mother and sister had died in prison and tries to convince him to give up his search. A Judah full of anger and hatred inside him is torn between his revenge on his executioner and his old childhood friendship. But he knows that Messala was not going to change and that his only option to take revenge for the supposed death of his family is to be able to defeat and humiliate him in the circus arena. For this, he would run the chariot race with the sheikh's white horses: Athais, Rigel, Aldebaran and Antares. Before the race, Sheikh Ilderim cannot contain himself and challenges Messala for a thousand gold talents if he beat him and for three thousand if he wins, but not before declaring that his charioteer was the circus champion Judah Ben Hur, despite which Mesala accepts the challenge.

Nine runners take part in the race, including charioteers from Assyria, Phoenicia, Cyprus, Athens, Judea and Rome. Judah Ben-Hur defeats Messala in his falcate chariot and his black Friesian horses, who ends up falling from his chariot and is fatally run over and trampled by another chariot as the last lap of the race begins. With his bloody body, he is definitely doomed to be mutilated in order to survive. Messala, in one last breath, tells Judah that his mother and his sister are alive, but isolated in the Valley of the Lepers. Therefore, as Judah intuits, they are doomed to a slow and horrible death.

Immediately Judah moves to the Valley of the Lepers, where to his surprise he finds Esther bringing food for her mother and sister. Ben-Hur asks for an explanation for the lie and tragically agrees to his mother's wish not to show himself. With his faith lost, he hates Esther and feels that his inner demons dominate him, so he decides to go to meet the governor Pontius Pilate and renounce his Roman citizenship, since his mother and sister are dead in life because of Rome. This insult is not well received by Pilate, so she becomes one more of the rebellious Jews in his eyes.

Judah decides to go to the Valley of the Lepers to the surprise of Esther and her mother, caring little about her illness and looking for Thirsa, her sister, who was dying in one of the caves. Devastated, he walks the streets of Jerusalem with his mother, his sister and Esther, acceding to her insistent request that they be healed by the rabbi of Galilee, whom he has heard preach and work wonders, while a procession of people shouts accompanies the March of the newly crucified, including a man who once gave the hero a drink. Ben-Hur, as thanks, tries to return his help with water. However, a Roman soldier spills the water before Jesus can drink and get some breath from his heavy load. This meeting and later witnessing the crucifixion of the man who one day saved him from dying, make Judah find peace and mitigate his anger through forgiveness. He returns still under the catharsis of what he has witnessed when he sees that his sister and her mother have been miraculously healed. Melted in a big hug, joy overflows.

Cast and characters

- Charlton Heston as Judah Ben-Hur: Protagonist of the story, is a Jewish aristocrat who is betrayed by his best friend, the Messala rostrum, and sent as a galley to the galleys. During a naval battle, he rescues the Roman consul Arrio and he adopts it, after which he returns to Judea in search of his lost family and revenge.

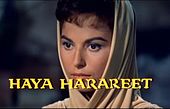

- Haya Harareet as Esther: Daughter of Simonides, at first appointed as a servant of Judah but both ended up falling in love. It has a primary role in caring for Ben-Hur's mother and sister when they suffer from leprosy.

- Jack Hawkins as Quinto Arrio: Roman Consul, meets Ben-Hur in the galleys and starts to be interested in his qualities, is saved by this in a naval battle against the pirates and Arrio adopts him as a son.

- Stephen Boyd as Messala: Roman Tribune and friend of Ben-Hur's childhood, to whom he ended up betraying with the desire to use it to intimidate the Jewish people and increase their power. He died at the hands of Judah in the quadrash race, not without saying, "Do you think the race is over? It is not over, Judah, and reveal to him that his mother and sister have not died: "Go out and find them in the Valley of the Lepers... if you can recognize them."

- Sam Jaffe as Simonides: Ben-Hur family butler. After he was arrested, he is tortured by Messala's orders and is crippled with his legs depending on a friend he met in prison.

- Hugh Griffith as Sheikh Ilderim: Hire Ben-Hur as a quadriple driver for his horses, as well as provide temporary protection.

- Finlay Currie as Baltasar: One of the magicians who visit Jesus of Newborn Nazareth at the beginning of the film. He is a friend of Sheikh Ilderim, with whom he knows Ben-Hur, and explains to this the existence of a savior and redeemer. His message influences the Jew until the end of the film.

- Martha Scott as Miriam: Mother of Ben-Hur and Tirzah, next to which she is arrested by the Romans accused of attacking the governor and locked in a prison, where she hires leprosy. Both are healed by Jesus at the time of the crucifixion and reunite with Judah at the end of the film.

- Cathy O'Donnell as Tirzah: Ben-Hur's younger sister. Like his mother, she is locked in a prison, where she hires leprosy, but she is healed by Jesus at the time of the crucifixion.

- Frank Thring as Pontius Pilate: Roman Governor of Judea. He meets Ben-Hur at the party of the Consul Arrio and is the one who decorates Judah after the quadried race. Ben-Hur recriminates him that the transformation of Mesala was by the evil of Rome.

- Terence Longdon as Druso: Assistant of Mesala, who is sent by him to gather information about Ben-Hur's mother and sister. Find out they're leper and order to get them out of the cell. He assists Mesala in his death after the squad race.

- George Relph as the Roman Emperor Tiberius.

- André Morell as Sexto.

- Claude Heater (not accredited) as Jesus of Nazareth: Secondary character in the film, but he has a great influence on both Ben-Hur and his family and friends. In the midst of his crucifixion he managed to heal Miriam and Tirzah and transform the heart of Judah to redemption. To achieve greater dramatic effect you never see your face.

Spanish dubbing

| Character | Fold actor | |

|---|---|---|

| Spain | Hispanoamérica | |

| Judah Ben-Hur | Rafael Navarro García (actor) | Blas García Victor Mares (original voice) |

| Fifth Arrio | Felipe Peña | Esteban Siller |

| Table. | Manuel Cano | Agustín López Zavala Rolando de Castro (original voice) |

| Ester | Irene Gutiérrez Caba | Patricia Martínez |

| Simonid | José María Angelat | Juan Domingo Méndez |

| Sheikh Ilderim | José María Ovies | Mario Sauret |

| Miriam | Maria Victoria Durá | Beatriz Aguirre |

| Tirzah | Elvira Jofre | Loretta Santini |

| Baltasar | Ramón Martori | Carlos Petrel |

| Pontius Pilate | Arsenio Corsellas | Sergio Barrios |

| Drususus | Vicente Vega | Eduardo Borja |

| Narrator (Baltasar) | Ramón Martori | Carlos Petrel |

Production

The production company Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) originally announced in December 1952 a remake of the 1925 silent film Ben-Hur, clearly to put its Italian lira currency assets to use Actors Stewart Granger and Robert Taylor were said to be favorites to star in the film. Nine months later, MGM announced that it would shoot the production in CinemaScope format and that filming would begin in 1954. By November 1953, producer Sam Zimbalist had been assigned to lead the project and screenwriter Karl Tunberg had been hired to write the script. Sidney Franklin was scheduled to direct and Marlon Brando to star. In September 1955, Zimbalist, who stated that Tunberg's script was now complete, announced that a six to seven-month shoot would begin in April 1956 in Israel or Egypt using MGM's new 65mm widescreen process. However, the production company MGM suspended production early ipios of 1956.

By the late 1950s, court decisions were forcing movie studios to divest their movie networks, and competitive pressure from television had thrown MGM into significant financial difficulties. to save the studio, and inspired by the success of the Biblical epic film The Ten Commandments produced by Paramount Pictures in 1956, studio head Joseph Vogel announced in 1957 that MGM would once again resume the The Ben-Hur project. Filming began in May 1958 and lasted until January 1959, while post-production lasted another six months. Although the initial budget was $7 million, In February 1958 it had already amounted to ten million and by the time filming began it had already exceeded fifteen million, which made it the most expensive film production shot up to then.

A major change in the film occurred in the opening credits. Concerned that the roar of the Lion of the Metro, the symbol of the production company, would create a bad impression with the opening scene of the Nativity, director William Wyler was given permission to replace the loud roar of the feline with its static and silent image.

Development

Lewis Wallace's 1880 novel Ben-Hur has 550 pages. Zimbalist hired several writers to shorten the story and write the screenplay. According to Gore Vidal, by the spring of 1958 twelve versions of the script had already been produced by various authors. Vidal himself had been asked to write his version, but he refused and that decision cost him a suspension. Karl Tunberg was one one of the last writers who worked on the script and eliminated everything that narrated the novel after the crucifixion of Jesus, omitted the subplot in which Ben-Hur simulates his own death and gathers a Jewish army to defeat the Romans, in addition to alter the way women are cured of leprosy. Zimbalist disliked this script by Tunberg, considering it "vulgar" and "impossible to shoot".

The writing process changed when the assigned director, Sidney Franklin, fell ill and left the project. Zimbalist offered the director's chair to William Wyler in early 1957, who decades earlier had been one of many assistant directors on the 1925 Ben-Hur. the script "very primitive, elemental". Zimbalist showed him some storyboards for the chariot race and informed him that MGM would be willing to spend up to $10 million, whereupon Wyler began to express interest in the film. MGM allowed Wyler to begin casting, and in April 1957 some media reported that the director was doing screen tests with some famous Italian actors, including Cesare Danova.

Wyler did not formally agree to direct the film until September 1957, and the production company did not announce his hiring until January 3, 1958. Despite not yet having his lead, Wyler accepted the job. for various reasons: he was promised a salary of $350,000 and 8% of box office receipts (or 3% of net profits, which was even more money), and he also wanted to shoot again in the city of Rome, where he had filmed the 1954 film Roman Holiday. His base salary was the most generous ever paid to a film director. Reasons of professional competitiveness also influenced his decision, since Wyler later admitted that he wanted to surpass the work of Cecil B. DeMille (director of The Ten Commandments). Wyler also joked that a Jew like him would have made a great movie about Jesus Christ.

Script

Wyler, like Zimbalist, was dissatisfied with the script, feeling that it was a morality game with political overtones and that the dialogue sounded too modern. Zimbalist hired two playwrights to draft it, first by S. N. Behrman (author of the screenplay for Quo Vadis? ) and later Maxwell Anderson. Vidal himself claims that he entered the project just after Anderson and that Fry was not involved until shortly before his departure from the film. Vidal arrived in Rome in early March 1958 to meet with Wyler. He said that the director he had not yet read the script and that, when he did so at the writer's insistence, he was disappointed by the excessive modernity of the dialogues. Vidal agreed to work on the script for three months to get out of suspension and fulfill his contract with MGM, although Zimbali st pressured him to try and get him to stay on for the entire production. At the time Vidal was researching to write a book about a 1st century Roman emperor IV d. C., Juliano, so he was a great connoisseur of Ancient Rome.

Vidal's style of work was to finish a scene and comment on it with Zimbalist. When they reached an agreement, they would show it to Wyler. Vidal said that he kept the structure of what Tunberg, Behrman and Anderson had written, but that he rewrote almost all the dialogue. In March 1959 Vidal admitted to William Morris that Fry returned to write almost a third of the dialogue that he had added to the first half of the film. However, Vidal made a structural change that was not reviewed. In Turnberg's script, Ben-Hur and Mesala meet and feud in a single scene, but Vidal divided it into two, so they both meet at the Antonia fortress and later argue and break their friendship at Ben-Hur's house.. Vidal also added some nuance to the characters, such as Messala buying Tirzah a brooch and Ben-Hur giving the Roman tribune a horse. Gore Vidal claimed to work on the first half of the script (ie, all the way up to the race). of chariots) and that he wrote ten versions of the scene in which Judah Ben-Hur confronts Messala and pleads for his family's freedom.

Vidal's claim that there is a homoerotic subtext is controversial. The subject first came up in an interview with the screenwriter in a 1995 documentary, The Hidden Celluloid, in which he claimed that he had convinced Wyler to instruct Boyd to play the role of a scorned homosexual lover. It seemed to the writer that Mesala's vengeance could only be motivated by a feeling of rejection typical of a lover, although Charlton Heston was not told this. Whether Vidal wrote the scenes that way, or whether he simply had a conversation with Wyler, and to what extent this carried over into the film remains a matter of debate. William Wyler himself said he did not remember any conversation on this subject, and also discarded Vidal's script in favor Fry's. However, Morgan Hudgens, the film's publicity manager, wrote to Vidal in May 1958 about this important scene and hinted that there was a homosexual context: "...[Charlton Heston] was really involved yesterday in your scene of "first meet". You should have seen those boys hug!" Film critic F. X. Feeney, who compared drafts of the Ben-Hur script, concluded that Vidal made many important contributions to the script.

The film's final writer was Christopher Fry. Charlton Heston commented that Fry was Wyler's first choice as a screenwriter, but that Zimbalist forced Vidal on him. Fry arrived in Rome in early May 1958 and spent six days a week on the set, writing and writing. rewriting both dialogue and entire scenes, until the film was finished. In particular, he gave the dialogue a slightly more formal and archaic tone, but without making it sound pompous and medieval. crediting of the film's script that implicated Wyler, Tunberg, Vidal, Fry and the Writers Guild of America.

The final script was 230 pages long and was substantially different from the 1880 novel on which the 1925 film Ben-Hur was based. Some changes made the story more dramatic and others inserted a certain admiration for the Jewish people, who had then just founded the state of Israel, and for the highly diverse American society of the 1950s, rather than the vision of "Christian superiority" that Lewis Wallace's novel possesses.

Cast Selection

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer opened a casting office in Rome in mid-1957 to select 50,000 people to play minor roles and as extras in the film. A total of 365 actors have dialogue in the film, although only 45 of them were considered "main" performers. When casting, Wyler emphasized characterization rather than the appearance of the actors or their character. film career. He cast British actors to play the Romans and Americans to play the Jews in order to clearly highlight the difference between the two groups. The Romans in Ben-Hur are aristocrats, so that Wyler thought that American viewers would assimilate the accent of the British English language as "patrick".

The role of Judah Ben-Hur was offered to several actors before it was accepted by Charlton Heston. Burt Lancaster turned down the role because he found the script boring and because he felt it belittled Christianity. Paul Newman also didn't accept it because he thought his legs didn't look good in a tunic. Other actors offered the role leading role were Marlon Brando, Rock Hudson, Geoffrey Horne and Leslie Nielsen, as well as other muscular and good-looking Italian actors, although most did not speak English. Kirk Douglas was interested in the role, but lost it in Heston's favor, who was formally hired on January 22, 1958. His salary was $250,000 for thirty weeks of shooting.

Stephen Boyd was cast on April 13, 1958 to play Messala, the story's main antagonist. William Wyler originally wanted Heston to play Messala, but had to find someone else once he was selected to play Ben-Hur. Since both actors had blue eyes, Wyler asked Boyd to wear brown contact lenses in order to more clearly differentiate between the two characters. Marie Ney was initially left with the role of Miriam, but she was fired after two days of filming because she was unable to cry at the appropriate moment. Heston stated that it was he who suggested to the director the hiring of Martha Scott for this role, an actress who was hired on 17 July 1958. Cathy O'Donnell, Wyler's sister-in-law, was cast in the role of Tirzah.

For the role of Esther, the names of more than thirty actresses were considered, although the Israeli Haya Harareet was finally chosen on May 16, 1958, a relatively novice interpreter who passed a camera test of only thirty seconds. Wyler had met her at the Cannes Film Festival, where he was impressed by her conversational skills and strength of personality. Sam Jaffe would play Simonides and Finlay Currie would play Balthazar, both hired on the same day. Wyler had to convince Jack Hawkins to appear in the film, as the actor did not want to act in another epic film after taking part in The Bridge on the River Kwai. Hugh Griffith, who had established a reputation in the With the post-war comedy films from Ealing Studios, he played the histrionic character of Sheikh Ilderim. The brief role of Jesus of Nazareth was played by the American opera singer Claude Heater, who was performing in Rome with l to the Vienna State Opera when he was asked to audition for the film. His name does not appear in the credits.

Photography

Robert L. Surtees, who had already worked on several of the most successful epic films of the 1950s, was selected as cinematographer. Early in production on Ben-Hur, Zimbalist, and other MGM executives made the decision to shoot the film in a widescreen format. Wyler disliked that format, of which he commented: "Nothing is left out of the picture, and you can't fill it in. Either you have a lot of empty space, or if you have two characters talking, there is a flock of people behind them surrounding them who have nothing to do with the scene." The cameras were very large and heavy and it took a long time to move them. To overcome these difficulties, Surtees and Wyler collaborated on using motion picture film's widescreen lenses and projection technologies to create highly detailed images for the film. Wyler was renowned for depth composition, a visual technique in which people, sets and architecture are not only composed horizontally, but also in depth of field. He also liked the long takes, during which the actors could move within that highly detailed space.

Ben-Hur was filmed using a process known as "MGM Camera 65", first used in The Tree of Life, released by MGM in 1957. This camera used special 65mm Eastmancolor film with an aspect ratio of 2.76:1. The Mitchell Camera Company developed and manufactured anamorphic camera lenses 70 mm according to the specifications sent by MGM. The movie film could be adapted to the requirements of each exhibition hall, so they did not have to install special 70 mm projection equipment, which was very expensive. six of these lenses were shipped to Rome to be used in filming, at a price of $100,000 each.

Shooting

Pre-production began at the Cinecittà studios in Rome around October 1957. MGM's art department produced more than 15,000 sketches and drawings of the clothing, sets, and props needed for the film, 8,000 of them just for the dresses. Each design was photocopied and cataloged for use by the production design team and craftsmen. Over a million props were built in total. The construction of miniatures for Quintus Arius's entry into Rome and for the The naval battle was already underway by the end of November 1957. MGM film location technicians arrived in Rome in August 1957 to identify possible filming locations.

Shooting in some North African location was seriously considered, so much so that in mid-January 1958 the production company stated that filming in Libya would begin on March 1 of that same year and that 200 camels and 2,500 horses had already been secured for production. filming was then scheduled to move to Rome on 1 April, where Andrew Marton had been hired as second unit director and seventy-two horses were being trained for the chariot race scene. However, the Libyan government canceled the filming permits for religious reasons on March 11, 1958, just a week before filming began in the country. Also for religious reasons, the Israeli government prohibited filming in the country when some shots had already been filmed near Jerusalem, footage that does not appear in the film.

Principal shooting began in Rome on May 18, 1958, when the script was still unfinished and director William Wyler had only read the first ten pages. Shooting days lasted twelve to fourteen hours, Six days a week. On Sundays, Wyler met with writer Fry and producer Zimbalist. The pace of shooting was so grueling that a doctor had to come to the set to inject anyone who asked for a B-complex vitamin, injections that Wyler and his family later suspected were tainted with amphetamines. To speed things up, Wyler often kept the lead actors on standby fully dressed and in character makeup to quickly shoot scenes if the first unit was late. Actresses Martha Scott and Cathy O'Donnell spent the entire month of November 1958 in the costumes and make-up of lepers so that Wyler could film their scenes when other takes were slow to progress. The director was not satisfied with the performance. Judah Ben-Hur did not make a credible character, so Heston had to repeat the phrase "I am a Jew" up to sixteen times. Filming lasted nine months, three of which were spent alone. in the complex chariot race. Filming ended on January 7, 1959, with the scene of the crucifixion of Jesus of Nazareth, which took four days to shoot.

I spent whole nights without sleeping trying to find a way to portray the figure of Christ. It was a terrible thing to deal with a theme recreated by all the great painters over twenty centuries, events of the life of the best-known man that ever existed. Anyone already has his own concept of it. I wanted to be respectful, but also realistic. A crucifixion is something bloody, terrible, atrocious, and a man does not go through it with a benign expression on the face. I had to deal with that. It's hard to do and not get complaints from anyone.William Wyler on the shooting of the Crucifixion of Jesus.

Production Design

Italy was Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer's first choice to host the shoot. However, the possibility of shooting in other countries such as France, Spain, Mexico or the United States was considered. One of the first decisions made was to shoot at the Cinecittà studios, huge film facilities built in 1937 on the outskirts of Rome. Zimbalist chose Henry Henigson, a regular Wyler collaborator, to oversee the film. William A. Horning and Edward Carfagno created the general look of the film based on the creative work that had been carried out for the production over the last five years. In the summer of 1956, a small group of technicians from the production company arrived at Cinecittà to start preparing the facilities of the Italian studios.

For the film Ben-Hur, three hundred filming sets were built that occupied sixty hectares and nine sound studios. Some sets that had been used for the filming of Quo Vadis? in 1951 were remodeled and reused in Ben-Hur. By the time production ended, 450,000 kg of plaster and 1,100 m³ of wood had been used. In the film's budget includes the ordering of 100,000 dresses and 1,000 complete armors, the hiring of 10,000 extras and the acquisition of hundreds of camels, donkeys, horses and sheep.

Costume designer Elizabeth Haffenden oversaw a team of 100 seamstresses who began crafting the clothes a year before shooting began. Special silk was imported from Thailand, armor was made in West Germany, and woolen garments were woven and embroidered in the United Kingdom and various South American countries. Also in the UK, various leather goods and garments were made, while boots, shoes and sandals were made by Italian craftsmen. Lace fabrics for dresses were bought in France and jewelery in Switzerland. Women from the Italian region of Piedmont donated more than 180 kg of hair to make wigs and false beards. In addition, three hundred meters of roads had to be created for the moving platforms of the heavy cameras. In a workshop where two hundred artists and craftsmen worked, hundreds of friezes and statues were created for the sets. A small mountain town located 64 km from Rome, Arcinazzo Romano, was the location chosen to simulate ancient Nazareth. It was also filmed on the beaches of Anzio and some caves located to the south of this town were the set of the leper colony. In Arizona, United States, some desert scenes were filmed.

The naval battle was one of the first scenes shot, between November and December 1957. For its recreation, forty miniatures of Roman triremes and several life-size 53m-long galleys were used, all of them capable of sailing. The miniatures were filmed in a huge water tank that was built at the MGM studios in Culver City, California. The life-size ships were recreated as faithfully as possible based on some plans of Roman galleys that were they are kept in Italian museums. In the Cinecittà studios, an artificial lake was created, large enough to accommodate the galleys, with mechanisms capable of generating the movement of sea waves. Behind this lake, a huge backdrop 61 m wide by 15 m high was placed, hiding the city and the hills in the background. To make the scene bloodier, Italian extras with amputated limbs were recruited. on which they simulated terrible injuries sustained during the battle. When editor John D. Dunning was editing the film, he had to cut out the appearance of these extras on screen so as not to upset viewers. The scenes shot on the deck of the galleys were convincingly integrated with the filming of the miniatures with the help of matte backgrounds during post-production.

One of the most sumptuous sets was the villa of Quintus Arius, which had forty-five perfectly functional fountains and more than 14 km of pipes. Some wealthy Roman citizens and nobles wanted to play their patrician ancestors in the film and therefore they acted as extras in the scenes of the villa. To recreate the streets of the ancient city of Jerusalem, a huge set measuring 1.3 km² in length was built, which included a replica of the Jaffa Gate from 23 m high. The sets were so enormous and spectacular that they became a tourist attraction, and several movie stars visited them during filming. These enormous structures could be seen from just outside Rome and MGM estimates that they were made Guided tours of the filming sets for more than five thousand people.

These monumental sets cost $125,000 to disassemble. Most of the filming equipment was turned over to the Italian government, which sold and exported it. MGM ceded the artificial lake to Cinecittà, although it retained control over the dresses and the huge curtain used on the lake, which were shipped to the United States along with the race cars, which were used as promotional props. Life-size galleys and pirate ships were dismantled to prevent them from being used by rival studios. Some of the horses were adopted by their handlers and others were sold. Many of the camels, donkeys, and other exotic animals were sold to zoos and circuses throughout Europe.

Assembly

For Ben-Hur, 340,000 m of film was shot. According to editor John D. Dunning, the first cut of the film was four and a half hours long, but director William Wyler wanted to cut the duration to less than three and a half hours. The most difficult editing decisions, according to Dunning, had to do with the scenes in which Jesus Christ appeared, since they had hardly any dialogue and most of the shots reflected only the gestural reaction of the audience. actors. Dunning also felt that in the final cut the leper scene was too long and needed trimming. The editing of the film was also complicated by the 70mm celluloid, since the Moviola used at the time could not process frames of that size. Therefore, it was necessary to reduce the footage shot on 70mm to 35mm film, which caused part of the image to be lost. The final cut of Ben-Hur lasts 213 minutes and includes 5,800 m of film, the third longest up to that moment, just behind the length of Gone with the Wind and The Ten Commandments.

Soundtrack

The film's music was composed and conducted by Miklós Rózsa, author of several soundtracks for Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer epic films, although producer Zimbalist's first candidate had been William Walton. the music of Greco-Roman antiquity to give his score an archaic sound combined with modernity. He himself conducted the MGM Symphony Orchestra, made up of one hundred instruments, during twelve recording sessions that totaled a duration of seventy-two hours. The soundtrack was recorded in six-channel stereo. More than three hours of music were composed for Ben-Hur, of which two and a half hours were spent, making it the band longest-running soundtrack in film history.

For his work, Rózsa was awarded the Oscar for Best Original Score and to this day remains the only score for an epic film set in Antiquity to win this award. Like most of soundtracks, it was put up for sale in an album for your enjoyment outside the film. The musical composition was so long that it had to be released in 1959 on three LP records, although a single LP version also appeared with Carlo Savina conducting the Rome Symphony Orchestra. In addition, in order to make an album easier to listen to, Rózsa arranged his composition in 1959 into a Ben-Hur Suite, released under Lion Records, a subsidiary of MGM. Since the 1960s he has been re-recorded and released numerous times.

The soundtrack of Ben-Hur is considered the best of Miklós Rózsa's career, as it exerted an obvious influence on other musical compositions until the mid-1970s, when the advent of John Williams and his scores for films such as Jaws, Star Wars or Raiders of the Lost Ark became popular among composers and moviegoers.

The chariot race

The chariot race scene, chariots drawn by four horses in a row, was directed by Andrew Marton and Yakima Canutt, regular second unit directors. Each had an assistant director filming additional material, among whom was Sergio Leone. Wyler filmed the pompous pre-race procession, footage of the cheering crowd, and the victory celebration scenes at the end of the race. the competition. The opening procession scene is traced frame by frame from the same sequence in the 1925 Ben-Hur. mainly with close-ups and medium shots. To impress viewers with the enormity of the Roman circus, Wyler wanted to show the procession in formation even though it was not historically accurate.

Set design

The oval-shaped track for the chariot race was built at the Cinecittà studios and recreates a Roman circus in Jerusalem. With an area of 7.3 hectares, it was the largest set ever built for a film. It cost a million dollars to erect it and the work of several thousand workers for an entire year to dig the oval in a quarry. The track was 460 m long and the stands were raised five stories. To raise the 400 km of metal tubes were used for the seating structures. The upper bleachers and mountainous landscape were simulated with pictorial backgrounds added in post-production. 36,000 tons of sand brought in from beaches were used to cover the racetrack from the Mediterranean.

Other elements of the Roman circus were also historically accurate, such as the three meter high spina (the central podium around which the chariots revolve), the metae (the ends of the spina, where columns stand), the dolphin-shaped turn counters and the carceres, a building with columns located at one end of the circus that was where horses and chariots were prepared before the competition. The four colossal statues located on the spina were more than 9 m tall. Another track was built next to the circus set of identical dimensions to train with chariots and horses and design the camera plans.

Preparation

The planning of the race scene lasted almost a year. In November 1957 seventy-two horses were purchased and imported from Yugoslavia and Sicily animals in the prime of their lives and physical condition that were trained by Glenn Randall to pull the chariots. The magnificent Arabian horses in Judah Ben-Hur's chariot were actually Purebred Spanish horses, while the rest of the horses were mostly Lipizzaners. two horses were commissioned by a veterinarian, a saddler and twenty stable boys, who ensured that the animals were ready and harnessed each day for the races. The firm Danesi Brothers built eighteen carriages weighing 410 kg each, nine of which were used solely for training. The lead actors and stuntmen circled the track a hundred times on the cars to prepare for filming the scene.

Both Charlton Heston and Stephen Boyd had to learn to drive the cars. Heston was an experienced rider and by practicing three hours a day he soon learned to master the vehicle. The actor had to wear contact lenses when riding to prevent sand from getting into his eyes. The other six drivers competing against Ben-Hur and Mesala were played by experienced Hollywood horsemen, including Giuseppe Tosi, who years before had been a bodyguard for King Victor Emmanuel III of Italy.

Shooting

Shooting the nine-minute race scene took five weeks spread over three months. It cost a million dollars in total and covered 200 miles on the cars to complete it. Marton and Canutt filmed the entire race with stuntmen, edited the sequence and showed it to Zimbalist, Wyler and Heston so they could see what it looked like. the scene and decide where the short shots of the two protagonists would be inserted. 7,000 extras were hired as spectators. The difficult economic situation in Italy at the time caused several thousand people to show up for the selection of extras more than necessary. The rejection of numerous extras on June 6 led to a riot at the studio gates in which stones were thrown and an assault was attempted that had to be repelled by police intervention.

To simulate the damage caused to the wheels by the spikes of the Mesala chariot, explosions of small charges of dynamite were used. To recreate the drivers run over by the chariots, three very realistic mannequins were placed in strategic places on the track. races. The cameras had some problems during filming. The 70mm lenses had a minimum focal length of fifteen meters and to follow the cars the cameras were mounted on an Italian car. However, the horses accelerated much faster than the carriage and it was very difficult to film the carriages at the proper distance. The production company had to buy a much more powerful American car, but it was also not fast enough to keep up with the fast trots of the equines, so directors Marton and Canutt had only a few seconds to get the shots they wanted. Over the weeks, a lot of filmed material accumulated, so that once the final editing was done, the ratio of footage filmed to footage used turned out to be 263:1, one of the highest in the history of cinema.

One of the most intense moments of the race occurred when Heston's stuntman, Joe Canutt, son of Yakima Canutt, was thrown into the air in a chariot jump and injured his chin in the fall. Marton wanted to keep the scene against Zimbalist's advice, so he devised to show Ben-Hur jumping onto his chariot and immediately recovering position, the horses continuing to run at full gallop. de Canutt was carefully cut and combined with a shot of Heston regaining control of the vehicle, creating one of the most memorable stunts of the race. Boyd performed all but two of his stunts. The one where Messala falls under the feet of the horses, Boyd wore steel armor under his tunic in the shot in which he is seen trying to hold on to the reins of the animals. The image of his body trampled by horses was made with a mannequin.

There are several urban legends surrounding the filming of the Ben-Hur race. One says that a stuntman died during filming, according to the actor Nosher Powell in his autobiography, and another says that a Ferrari car can be seen in one of the shots. The book Movie Mistakes demonstrates that both are mere myths. Heston mentions in the commentary for the DVD edition of the film that he supposedly wears a watch on his wrist during the race, but clarifies that it is only he wore leather armor up to the elbow.

Premiere

For the promotion of Ben-Hur, a huge advertising campaign was launched that cost 14.7 million dollars. MGM created a special department that was dedicated to conducting surveys in more than two 1,000 high schools in forty-seven American cities to survey adolescent interest in the film. A school guide was also created and distributed to study centers. Sindlinger and Company was contracted to survey citizens from all over the United States to find out the impact of the promotional campaign. Between 1959 and 1960 candy, chariot-shaped tricycles, costumes, hair ornaments, jewelry, perfumes, towels, toy swords, helmets, and swords were sold. Roman umbrellas, and fictionalized versions of the film's story worth more than $20 million.

The premiere of the film was held at the Loew Theater in New York on November 18, 1959. There were present, among others, William Wyler, Charlton Heston, Stephen Boyd, Haya Harareet, Martha Scott, the Mexican Ramón Novarro (who played Judah Ben-Hur in the 1925 silent version), Spyros Skouras (president of 20th Century Fox), Barney Balaban (president of Paramount Pictures), Jack Warner (president of Warner Bros.), Leonard Goldenson (president of American Broadcasting Company), Moss Hart (playwright), Robert Kintner (ABC Television executive), Sidney Kingsley (playwright), and Adolph Zukor (founder of Paramount Pictures).

Fundraising

In its first theatrical release the film grossed $33.6 million at the North American box office (the distributor's share of the box office), although it actually generated $74.7 million in ticket sales. Outside of North America, it grossed another $32.5 million, bringing its total gross to $66.1 million. second highest-grossing film in cinema history up to that time, behind only Gone with the Wind. Ben-Hur saved production company Metro-Goldwyn- Mayer from financial disaster, since it left him a profit of just over 20 million dollars in its first release and another 10 million when it was re-released in 1969. In 1989, Ben-Hur it had left $90 million in profits from its theatrical release around the world.

Critical reception

Ben-Hur received overwhelmingly positive reviews upon its release. Bosley Crowther of The New York Times wrote that it was "a highly intelligent and gripping human drama"., while praising Wyler's work and the impressive chariot race: "There is little in film to compare the chariot race. It's an impressive ensemble of powerful set-up, thrilling action with horses and men, sweeping vistas, and an overwhelming use of dramatic sounds." United Press International's Jack Gaver also had praise for the performances, describing them as "genuinely warm and fervor, with intimate scenes very well acted". Philip K. Scheuer, of Los Angeles Times , defined it as "magnificent, inspiring, impressive, passionate and all the other adjectives you've heard about it", although he also said that the editing was abrupt at times. Ronald Holloway, writing for Variety, said that Ben-Hur was "a majestic achievement, representing excellent mixture of cinematic arts and master craftsmen", concluding that Gone with the Wind, also from MGM, would eventually have to take a backseat. On the career, he added that "it will probably be preserved in the film archives as the best example of the use of the camera to film an action scene. The race, directed by Andrew Marton and Yakima Canutt, is about 40 minutes of the most hair-raising action spectators have ever seen."

But there were also negative reviews. Bosley Crowther found the film too long, while Scheuer generally praised it, opining that his biggest flaw was "exaggeration". He also criticized Charlton Heston for finding him more physically competent than emotionally. John McCarten of The New Yorker was even more critical of the lead for his poor diction. Even director William Wyler admitted time later privately that he was not very pleased with Heston's performance. Film critic Dwight Macdonald was also negative, finding it so slow-moving that "I felt like a motorist stuck at a railroad crossing waiting for a long freight train passes by". in a Sunday school". Many French and American critics who believed in the auteur theory saw the film as confirmation that William Wyler was merely "a commercial craftsman" rather than a serious artist.

Awards

Ben-Hur was nominated for 12 Oscars and won 11, a number of awards no film had ever won before and an achievement unmatched until the release of Titanic in 1997 and The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King in 2003. The only award for which it was nominated and did not win was Best Adapted Screenplay, which went to A place at the top, something some blame on the dispute over crediting the script. MGM and Panavision shared a Special Technical Oscar in March 1960 for the development of Camera 65's photographic process.

Ben-Hur also won three Golden Globe Awards (Best Motion Picture Drama, Best Director, and Best Supporting Actor for Stephen Boyd) and Andrew Marton received a Special Award for directing the sequence of the race. Heston was nominated for a Golden Globe Award for Best Actor in a Drama, but did not win. The film also won the BAFTA Award for Best Picture, the New York Film Critics Circle Award for Best Picture, and at the Directors Guild Awards, William Wyler was honored for his "masterful direction."

Ben-Hur also appears on several of the prestigious lists compiled by the American Film Institute, an independent non-profit organization founded in 1967 by the US National Endowment for the Arts. The AFI 100 Years... series was created by a jury of 1,500 artists, experts, critics, and historians with films selected based on their popularity over time, their historical significance, or their cultural impact. Both the film and its two protagonists, Judah Ben-Hur and Mesala, are included in several of its prestigious lists. In 2004, the National Film Preservation Board selected Ben-Hur for preservation in the National Film Registry for being a "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant" film.

Domestic Editions

Ben-Hur has been released several times for home viewing formats, most recently on DVD and Blu-ray Disc. On March 13, 2001, it was released in the United States on a double-sided DVD disc in widescreen format that included various extras, such as a commentary by Charlton Heston, a documentary about the filming (which had been prepared for the Laserdisc edition). of the film in 1993), screen tests, and a photo gallery. black, reproductions of cast member autographs, a 35mm celluloid still, and a reproduction of the original Ben-Hur poster by 69 × 102 cm. On September 13, 2005, another DVD edition of the film was released, this time with four discs that included, among other things, remastered image and sound and the 1925 silent film.

In 2011, Warner Home Video released a 50th Anniversary edition of Ben-Hur on Blu-Ray disc and DVD, presenting the film for home viewing for the first time in original aspect ratio. For this special occasion, the film was fully restored frame by frame from an 8K resolution scan of the original 65mm negative. The restoration cost $1 million and was one of the highest resolution restorations Warner Bros. had ever done.

Contenido relacionado

Mahjong

Basque Country

My neighbor totoro