Beauty

Beauty is commonly described as a quality of entities that makes them pleasant to perceive. Such entities may include landscapes, sunsets or sunrises, night skies, people, animals, plants, works of art, etc. Beauty is an abstract notion linked to many aspects of human existence. Beauty is studied within the philosophical discipline of aesthetics, in addition to other disciplines such as history, sociology, and social psychology. Beauty is defined as the characteristic of a thing that through a sensory experience (perception) provides a sensation of pleasure or a feeling of satisfaction. It comes from manifestations such as shape, visual appearance, movement and sound, although it is also associated, to a lesser extent, with flavors and smells. Along these lines and emphasizing the visual aspect, Thomas Aquinas defines beauty as that which pleases the eye (quae visa placet).

The perception of "beauty" often involves the interpretation of some entity that is in balance and harmony with nature, and can lead to feelings of attraction and emotional well-being. Because it constitutes a subjective experience, it is often said that "beauty is in the eye of the beholder". Although such relativism is exaggerated and is usually associated with worldviews and fashions, the fact is that there are objects and beings that give the impression of beauty already from their natural objectivity because they correspond to the natural requirements of homo sapiens, for example: the sweet taste is preferred to the bitter taste because the bitter one usually corresponds to toxic, the same as the fragrance of Many flowers are naturally preferred by mentally healthy people to putrid stench.

One difficulty in understanding beauty is due to the fact that it has both objective and subjective aspects: it is seen as a property of things but also as dependent on the emotional response of observers. It has been argued that the subject's ability to perceive and judge beauty, sometimes known as the 'sense of taste', can be trained and that expert verdicts agree in the long run. This would suggest that the validity standards of beauty judgments are intersubjective, that is, dependent on a group of judges, rather than completely subjective or completely objective. . Conceptions of beauty aim to capture what is essential in all beautiful things. The classical conceptions define beauty in terms of the relationship between the beautiful object as a whole and its parts: the parts must be in the correct proportion to each other and thus compose an integrated harmonious whole. hedonistic conceptions include the relationship with pleasure in the definition of beauty by maintaining that there is a necessary connection between pleasure and beauty, for example, that for an object to be beautiful it must cause pleasure disinterested. Other conceptions include defining beautiful objects in terms of their value, a loving attitude towards them, or their function.

Overview

Beauty, along with art and taste, is the main theme of aesthetics, one of the main branches of philosophy. Beauty is often classified as an aesthetic property in addition to other properties, such as grace, elegance or the sublime. As a positive aesthetic value, beauty is contrasted with ugliness as its negative counterpart. Beauty is usually listed as one of the three fundamental concepts of human understanding, in addition to truth and goodness.

The objectivists or realists see beauty as an objective or mind-independent characteristic of beautiful things, which is denied by the subjectivists i>. The source of this debate is that beauty judgments seem to be based on subjective grounds, that is, our feelings, and at the same time claim universal correctness. This tension is sometimes called "antinomy of taste" (antinomy of taste). Supporters of both sides have suggested that a certain faculty, commonly called the sense of taste, is necessary to make reliable judgments about beauty. David Hume, for example, suggests that this faculty can be trained and that the verdicts of experts agree in the long run.

Beauty is mainly discussed in relation to concrete objects accessible to sensory perception. It is often suggested that the beauty of a thing arises from the sensory characteristics of this thing. But it has also been proposed that abstract objects such as stories or mathematical proofs can be beautiful. Beauty plays a central role in works of art, but there is also beauty outside the field of art, especially with regard to the beauty of nature. nature. An influential distinction between beautiful things, due to Immanuel Kant, is that between dependent and free beauty (dependent and free beauty). A thing has dependent beauty if its beauty depends on the conception or function of this thing, as opposed to free beauty or absolute beauty. Examples of dependent beauty include an ox that is beautiful like an ox but not like a horse, or a photograph that is beautiful because it depicts a beautiful building but lacks overall beauty because of its low quality.

Objectivism and subjectivism

Beauty judgments seem to occupy an intermediate position between objective judgments, for example, about the mass and shape of a grapefruit, and subjective tastes, for example, about whether the grapefruit tastes good. The judgments beauty differ from the former because they are based on subjective feelings rather than objective perception. But they also differ from the latter in that they claim universal correctness. This tension is also reflected in common language. On the one hand, we talk about beauty as an objective characteristic of the world that is attributed, for example, to landscapes, paintings or human beings. The subjective aspect, on the other hand, is expressed in sayings such as "beauty is in the eye of the beholder".

These two positions are often referred to as objectivism or realism and subjectivism. Subjectivism has developed more recently in Western philosophy. The objectivists maintain that beauty is a characteristic of things independent of the mind. In this account, the beauty of a landscape is independent of who perceives it or whether it is perceived at all. Disagreements may be explained by the inability to perceive this feature, sometimes "lack of taste" (lack of taste). subjectivism, on the other hand, denies the existence of mind-independent beauty. Influential in the development of this position was John Locke's distinction between primary qualities, which the object has independently of the observer, and secondary qualities, which constitute powers in the object to produce certain ideas in the observer. When applied to beauty, there is still a sense in which it depends on the object and its powers. But this account makes the possibility of genuine disagreements over claims of beauty implausible, since the same object can produce very different ideas in different observers. The notion of "taste" it can still be used to explain why different people disagree about what is beautiful. But there is no objectively right or wrong taste, there are just different tastes.

The problem with both the objectivist position and the subjectivist position in its extreme form is that each has to deny some intuitions about beauty. This topic is sometimes discussed under the label 'antinomy of taste'. It has led a number of philosophers to search for a unified theory that can take all of these insights into account. A promising route to solving this problem is to move from subjective to intersubjective theories, which hold that the validity standards of taste judgments are intersubjective or depend on a group of judges instead of being objective.. This approach tries to explain how genuine disagreement about beauty is possible despite the fact that beauty is a mind-dependent property, dependent not on an individual but on a group. A closely related theory views beauty as as a secondary property or response-dependent (response-dependent). In one such account, an object is beautiful "if it causes pleasure by virtue of its aesthetic properties". The problem that different people respond differently can be addressed by combining response dependency theories with so-called ideal-observer theories: it only matters how an ideal observer would respond. There is no general agreement on how they should be defined the "ideal observers," but are often assumed to be experienced judges of beauty with a fully developed sense of taste. This suggests a roundabout way of resolving the antinomy of taste: Instead of looking for necessary and sufficient conditions of beauty itself, we can learn to identify the qualities of good critics and trust in their judgments. This approach only works if unanimity is guaranteed among the experts. But even experienced judges can disagree in their judgments, which threatens to undermine ideal observer theories.

Conceptions

Various conceptions of the essential characteristics of beautiful things have been proposed, but there is no consensus on which is correct.

Classical

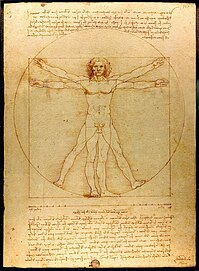

The classical conception defines beauty in terms of the relationship between the beautiful object as a whole and its parts: the parts must be in the correct proportion to each other and thus compose an integrated harmonious whole. In this story, which found its most explicit articulation in the Italian Renaissance, the beauty of a human body, for example, depends, among other things, on the correct proportion of the different parts of the body and overall symmetry. One problem with this conception is that it is difficult to give a general and detailed description of what is meant by "harmony between parts". the suspicion that defining beauty through harmony only results in trading one unclear term for another. Some attempts have been made to dispel this suspicion by looking for laws of beauty, such as the golden ratio. Alexander Baumgarten, for example, saw laws of beauty in analogy with laws of nature and believed that they could be discovered through empirical investigation. But these attempts have failed. until now to find a general definition of beauty. Several authors even claim the opposite, that such laws cannot be formulated, as part of their definition of beauty.

Hedonistic

A very common element in many conceptions of beauty is its relationship with pleasure. Hedonism considers that this relationship is part of the definition of beauty by maintaining that there is a necessary connection between the pleasure and beauty, for example, that for an object to be beautiful it must cause pleasure or that the experience of beauty is always accompanied by pleasure. This account is sometimes called "aesthetic hedonism" to distinguish it from other forms of hedonism. An influential articulation of this position comes from Thomas Aquinas, who treats beauty as "what pleases in the very apprehension of it". Immanuel Kant explains this pleasure through a harmonious interaction between the faculties of understanding and imagination. Another question for hedonists is how to explain the relationship between beauty and pleasure. This problem is similar to the Euthyphro dilemma: is something beautiful because we enjoy it or do we enjoy it because it is beautiful? Identity theorists solve this problem by denying that there is a difference between beauty and beauty. and pleasure: they identify beauty, or its appearance, with the experience of aesthetic pleasure.

Hedonists often restrict and specify the notion of pleasure in various ways to avoid obvious counterexamples. An important distinction in this context is the difference between pure and mixed pleasure. Pure pleasure excludes any form of pain or unpleasant feeling, while the experience of mixed pleasure can include unpleasant elements. But beauty can imply mixed pleasure, for example, in the case of a beautifully tragic story, which is why mixed pleasure is often allowed in hedonistic conceptions of beauty.

Another problem facing hedonistic theories is that we derive pleasure from many things that are not beautiful. One way to approach this problem is to associate beauty with a special kind of pleasure: aesthetic or disinterested pleasure. A pleasure is disinterested if it is indifferent to the existence of the beautiful object or if it did not arise due to an antecedent desire through means-end reasoning. For example, the joy of looking at a beautiful landscape would still be valuable if this experience turned out to be an illusion, which would not be true if this experience turned out to be an illusion. joy would be due to seeing the landscape as a valuable real estate opportunity. Opponents of hedonism often admit that many experiences of beauty are pleasurable, but deny that this is true in all cases. For example, a cold and tired critic can still She may be a good judge of beauty due to her years of experience, but she lacks the joy that initially accompanied her work. One way around this objection is to allow responses to beautiful things to lack pleasure while insisting that all s beautiful things deserve pleasure, that aesthetic pleasure is the only adequate response to them.

Others

Various other conceptions of beauty have been proposed. G. E. Moore explains beauty with respect to intrinsic value as "that whose admiring contemplation is good in itself". This definition connects beauty with experience while managing to avoid some of the problems often associated with subjectivist positions, as it allows things to be beautiful even if they are never experienced. Another subjectivist theory of beauty comes from George Santayana, who suggests that we project pleasure onto the things we call "beautiful". Thus, in a process resembling a category error, we treat our subjective pleasure as an objective property of the beautiful thing. Other conceptions include defining beauty in terms of a loving or longing attitude towards the beautiful object or in terms of its utility or function. Functionalists may follow Charles Darwin, for example, in explaining beauty in terms of its role in sexual selection.

History of beauty

One of its mental qualities could be traced back to the very existence of humanity. The Pythagorean school saw an important connection between mathematics and beauty. In particular, they noticed that objects that possess symmetry are more striking. Classical Greek architecture is based on this image of symmetry and proportion. Plato made an abstraction of the concept and considered beauty an idea, of independent existence to that of beautiful things. According to the Platonic conception, beauty in the world is visible to all; However, said beauty is only a manifestation of true beauty, which resides in the soul and which we can only access if we delve into its knowledge. Consequently, earthly beauty is the materialization of beauty as an idea, and every idea can become earthly beauty through its representation.

Beauty has generally been associated with the good. In the same way, the opposite of beauty, which is ugliness, has often been linked to evil. Witches, for example, are often attributed unsightly physical traits and repulsive personalities. This contrast is represented in tales such as Sleeping Beauty, by Charles Perrault. interior than on the external, so that what he contemplates is exempt from evil and feels in harmony with him and with the world.

Symmetry is important because it gives the impression that the person grew up healthy, with no visible flaws. Some researchers have suggested that neonatal traits are intrinsically attractive. Youth in general is associated with beauty.

There is evidence to suggest a beautiful face in child development, and that norms of attractiveness are similar in different cultures. Average, symmetry, and sexual dimorphism in determining beauty may have an evolutionary basis. Meta-analyses of empirical research indicate that all three characteristics produce attraction in both male and female faces and across different cultures. Facial attractiveness may be an adaptation for mate choice, possibly because symmetry and the absence of flaws signal important aspects of the mate's physical quality, such as health. These preferences are likely simply instincts.

Greek and Roman artists also held the standard for male beauty in Western civilization. The ideal Roman was defined as a tall, muscular, long-legged chief, with a chest full of thick hair, a high broad forehead -a sign of intelligence-, large eyes, a strong nose and perfect profile, a small mouth, and a powerful jaw. This combination of factors would produce a stunning look of handsome masculinity. With the notable exceptions of body weight and fashion styles, beauty norms have been fairly constant across time and place.

In ancient Chinese, a sign meaning "beautiful" is written, but today it is combined with two other signs meaning "great" and "sheep". Possibly, the large sheep was representative of beauty.

The Mayan culture considered that having squints was beautiful, and to achieve this, mothers placed jars in front of their children so that they would grow up with this defect; the concept of beauty can vary between cultures.

Human beauty

The characterization of a person as "beautiful," either individually or by community consensus, is often based on a combination of inner beauty, including psychological factors—such as such as congruence, elegance, charm, grace, integrity, intelligence, and personality —, and outer beauty, that is, physical attractiveness, which includes physical factors —such as youth, mediality, bodily health, sensuality, and symmetry. —.

Commonly, external beauty is measured based on the general opinion or consensus of a group of people. An example of this are beauty pageants, such as Miss Universe. Internal beauty, however, is harder to quantify. An important indicator of physical beauty is "average." When images of human faces are averaged to form a composite image, it becomes progressively closer to the "ideal" image and is perceived as more attractive. This phenomenon was first noticed in 1883, when Francis Galton, cousin of Charles Darwin, constructed composite images by superimposing photographs of vegetarians and criminals in search of a characteristic appearance for each of them. In doing so, he found that the resulting composite images were more attractive compared to any of the individual photographs.

Ugliness

Ugliness is a property of a person or thing that is not pleasant to look at. In many societies the judgment of being considered "ugly" is equivalent to being unsightly, repulsive or offensive. Like its opposite, beauty, ugliness implies a subjective judgment and is, at least in part, in the "eye of the beholder", the influence exerted by the culture of "observer". Thus, the perception of ugliness can be wrong or myopic, as in the story of The Ugly Duckling by Hans Christian Andersen.

Although ugliness is normally considered a visible characteristic, it can also be an internal attribute. For example, a person may be considered attractive on the outside but thoughtless and cruel on the inside. It is also possible to be in a "bad mood," which is an internal state of temporary unpleasantness.

Ugliness has its origin in the consideration of the "observing eye" and of the self-esteem that develops in people when they see the stereotypes of men and women that are pleasing to our senses of perception.

Beauty in art

In classical Greece, one of the main themes of the first half of Plato's Phaedrus is Beauty.

Contenido relacionado

Nepali flag

Silver openwork

UK art