Beatus of Liebana

The Beatus of Liébana (Liébana, c. 730 (?) - Liébana, c. 798 (?)), also called Saint Beatus, was a monk of the Monastery of San Martín de Turieno (now Santo Toribio de Liébana), in the Liébana region, foothills of the Picos de Europa in Cantabria (Spain). Beato de Liébana was a monk who dedicated himself to writing manuscripts. His best-known work is the Commentary on the Apocalypse of Saint John ( Commentarium in Apocalypsin ) in twelve books, of great influence during the High Middle Ages, in the fields of theology, politics and geography.

Some not entirely reliable sources say that the Blessed would later retire to the monastery of Valcavado in Palencia, where he would be named abbot —according to Alcuin of York— and would finally meet his death.[citation required]

In Cantabria, as well as in Asturias, they feel great devotion to this figure. Registered in the Catholic saints, his festival is celebrated on February 19.

Biography

Some historians think it came from Toledo, or even Andalusia.[citation needed] Perhaps he chose this monastery in Liébana due to its proximity to Covadonga and Cosgaya, places that the Christians of the time considered miraculous.

The Blessed quickly acquires a reputation for great erudition. He even became tutor and confessor for the daughter of Alfonso I, the future queen Adosinda, who would marry King Silo of Asturias, monarch from 775 to 783, for some time.

His notoriety had other causes besides his Commentary on the Apocalypse. A militant and energetic thinker, he fights those who compromise with the Muslim invaders, starting with the Archbishop of Toledo Elipando de Toledo, whom he accuses of heresy for defending adoptionism.

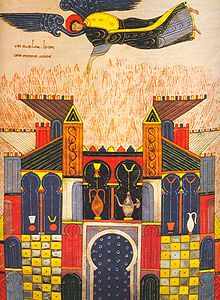

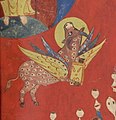

As Eduardo Manzano Moreno has pointed out, his Commentary on the Book of Revelation is an «interpretation of the difficult work of the apostle Saint John. One of the themes developed in that work was that of the heavenly Jerusalem». «His commentary of his on the Apocalypse acquired an enormous resonance and numerous manuscripts were made of it; manuscripts many times illuminated with fantastic images that make up a whole set —the so-called "Blesseds"— that constitutes one of the peaks of medieval iconography».

The adoptionist lawsuit

At the end of the VIII century, Elipando de Toledo, Archbishop of Toledo, then under the rule of the Emirate of Córdoba, defended the adoptionism that affirmed that the Father had adopted the Son, since his "nature" was not divine but human, having been conceived by a woman. As the prestige of the Toledo headquarters was still maintained Throughout the Iberian Peninsula, despite the fact that it was subject to the Emir of Córdoba, Elipando's "adoptionist" proposal provoked a fierce response in the Kingdom of Asturias led by the monk Beato de Liébana, possibly abbot of a monastery and very well connected with Queen Adosinda. Beato de Liébana accused Elipando of madness, heresy and ignorance and came to call him "testicle of the Antichrist". According to Eduardo Manzano Moreno, the controversy between Elipando and Beato de Liébana was "spurred by the strong struggle between a northern church, increasingly independent, and the old Visigothic church, whose main episcopates had fallen into Andalusian territory". 794 the Council of Frankfurt presided over by Charlemagne condemned adoptionism. In one of its canons it was said that this "heresy should be radically extirpated from the Holy Church".

Works

Undoubtedly Beatus' authorship is Apologeticum adversus Elipandum, a two-volume work that he wrote with Eterio de Osma, to confront the adoptionist heresy of the Archbishop of Toledo, Elipando.

The hymn O Dei Verbum, which is made up of phrases and concepts taken from the Commentary to extol and promote the patronage of Santiago over northern Christian Hispania, in need of the divine help. A few years later, the tomb of the apostle would be discovered in Santiago de Compostela.

Another work attributed to the Blessed and preserved in a fragmentary manuscript from the X century (in Santillana del Mar), it is a Liber Homiliarum for liturgical use. They are homilies that follow the readings of the mass or the office of matins, according to the Mozarabic calendar.

The Blessed

The manuscripts from the 10th to the 13th centuries, more or less abundantly illustrated, are known as «The Beatos», where the Apocalypse of Saint John and the Commentaries on this text written in the 18th VIII by the Blessed of Liébana. He wrote the Commentaries on the Apocalypse of Saint John (Commentarium in Apocalypsin), in the year 776. Ten years later, in 786, he wrote the final version. In this version he tries to face the crisis that the Church was going through in those years and tries to demonstrate that he is in possession of the traditio about the arrival and preaching of the Apostle Santiago in Hispania. For this he bases himself on certain writings from the Breviary book of the Apostles.

These Commentaries also contain one of the oldest world maps of the Christian world.

Historical context: the Kingdom of Asturias

Romans and Barbarians

In the year 379, Emperor Gratian chose a Spanish general, Theodosius (or Theodosius I, also known as Theodosius the Great) to occupy the throne of the Eastern Empire. He, after removing a usurper from the Western throne in 388, reigned over the entire Roman Empire.

After converting to Christianity in 380, he made it the official religion of the Empire, forbidding the Arian heresy, pagan cults, and Manichaeism.

The unification of the Empire was short-lived: on Theodosius' death, the Empire was divided between his two sons.

On December 31, 406, various Germanic peoples crossed into Gaul. The Suevi settled in Galicia (northwest of Spain), the Vandals and the Alans settled in Andalusia.

During this time, Ataúlfo, chief of the Visigoths, and successor of Alaric I, married Galla Placidia, the daughter of Emperor Theodosius I the Great, in 414. But, pushed by the Ravenna government, he moved to Hispania, which would cause the wars between the barbarians to multiply in the Iberian Peninsula.

At the same time, these towns underwent a "romanization". Thus the Visigoths join a Roman coalition headed by the general Flavio Aecio, being King of the Visigoths Theodoric I, to confront the alliance of the Huns commanded by their king Attila. The Battle of the Catalaunic Fields, in which Theodoric died, took place near Orleans in 451.

Shortly thereafter, the king of the Visigoths, Euric, traveled to Spain and proclaimed himself its first independent king. The Roman Empire had ceased to exist. Euric, faithful to the doctrines of Arius, urged the Suevian king to convert to Arianism.

Arianism in Hispania and the return of Catholicism

In 325, Bishop Osio of Córdoba was summoned by Emperor Constantine to the first ecumenical council in Nicaea to condemn the doctrines of Arius (Jesus Christ the servant of God).

The Visigoths, also Arians, helped to spread the heresy throughout the peninsula. Despite the fact that only 5% of the population practiced it, they made Arianism the official state religion.

After this, the Catholic clergy took refuge in rural areas.

At the beginning of the VI century, the Visigothic king Leovigild married Theodosia, the sister of Isidore of Seville. Isidore tried to reconcile the Visigoths with the "Hispano-Romans" and he agrees with the Nicene Creed as to the nature of Christ. One of his sons married a Christian granddaughter of Clovis. The other, Recaredo, converted to Christianity in 587 and officially abjured Arianism at the Council of Toledo (589), dragging with him the queen, the court and the heretic Visigothic bishops.

The Archbishop of Toledo remains as primate of Hispania, and the Church is supported by the sovereigns. These appoint bishops who, in return, exercise control over the royal administration.

But the Visigoths must face epidemics, famines, incursions by Franks. The succession wars devastate the country. An aspirant to the throne of Toledo, Agila II, refugee in Ceuta (Mauritania in antiquity), to guarantee victory over his enemy Rodrigo, asks for the help of troops from the Maghreb. Thus, in 711, Tariq ibn Ziyad crossed the strait whose name is henceforth associated with his.

Expansion of Islam and Christian resistance

Tariq's 7,000 men were not Arabs but Berbers, of whom the Arabs, who will soon occupy North Africa, were allies, although this alliance had its low points because the Berbers were treated as Muslims 'second-class. And this antagonism between the two ethnic groups will weaken the new Muslim masters of Hispania, which is now called Al-Andalus.

In three years the Peninsula was occupied, with the exception of a part of the Cantabrian mountain range (future kingdom of Asturias) that forms in the northwest of the country a kind of fortress whose peaks often reach more than 2000 meters, and even more 2600 meters in the Picos de Europa. Very soon Christians come to take refuge there, particularly from Toledo. Pelayo, is elected chief of the rebels with whom he will attack the Berber garrisons.

Quietly settled in Córdoba, or engaged in raids in southern Gaul, Muslim forces do not care about rebellion at first. However, an expedition is sent to Asturias. But there, Pelayo, pretending to flee, lures Berbers and Arabs to the Covadonga gorges, divides them into groups, and according to the legend he has just exterminated them in large numbers near Liébana. From then on, the kingdom of Asturias was consolidated around Cangas de Onís, with Pelayo as king.

Arabs and Mozarabs

While Asturias is becoming stronger and more populated, the Christians living under Muslim rule find themselves in the same situation as before under the rule of the Arian Visigoths. Subject to taxes that are increased only to them, they have no right to build new churches or found new convents. Once again, there are many who take refuge in the countryside, while the invaders remain in the cities. Again the hermitages appear in remote places. Christians living on Muslim land cannot practice their religion unless they first swore allegiance to a Moorish chief.

In 791, the Asturian king Alfonso II the Chaste moved the capital of the kingdom to Oviedo.

In this historical context, and in a region where the fleeing from Islam were contributing a very rich culture, particularly in the artistic field, it is in which Beatus (Blessed for Hispanics), a monk in a convent in the valley of Liébana, writes his commentary on the Apocalypse.

The Apocalypse Commentary

Description

It is a work of scholarship but without great originality, made mostly of compilations. The Blessed takes more or less long extracts from the texts of the Fathers and Doctors of the Church; in particular, Saint Augustine, Saint Ambrose, Saint Irenaeus, Saint Isidore. There is also the commentary on the Book of Daniel by Saint Jerome.

The organization of the work is judged by some[who?] as clumsy, and the text sometimes redundant or contradictory. Far from a work that exudes a strong and deep personality, we are in the presence of a somewhat timorous production, which does not show a great spirit of innovation. How could such a book, written in 776 and altered ten years later, have had such an impact for four centuries? If the part of the Blessed is very small, the work contains, on the contrary, a complete Latin translation of the Apocalypse of John, which can partly explain its notoriety.

The apocalyptic genre and its history

The Apocalypse of John is the last book in the Christian Biblical corpus. The apocalyptic literary class (from the Greek apocalupteïn, to reveal) that flourished in the intertestamental period (between the 2nd and 1st centuries BC) finds its roots, not in the New Testament, but in the last books of the Old, in particular, some parts of the Book of Daniel (written around 167 BC): the Apocalypse thus has more conceptual and contextual relationships with the Semitic culture of the Old Testament than with the world of the Gospels. The Apocalypse of John was written in the last third of the I century, during the persecutions of Nero, after that of Domitian against Christians who refused to worship the Emperor.

An apocalypse is a "discovery" of the future, revealed to a soul and transcribed in a more or less cryptic poetic form. It is an eschatological discourse. The Apocalypses were described as "Gospels of Hope", since they announce to martyred populations that historical evil achieves eternal happiness. The text seems generally obscure to those who are not immersed in biblical culture: intended only for believers, it refers to Holy History and prophetic books of the Old Testament. That is why its "political" escape the pursuers. It is therefore a conception of History (a "Theology of History", wrote Henri-Irénée Marrou) destined to show those who suffer how the Supreme Good will be found at the end of a historically necessary march through the wrong.

The message

The Apocalypse is presented as the book of Christian resistance. The great symbols take on a new meaning. The Animal, which designated the Empire, becomes the name of the emirate (later converted into a caliphate) - Babylon is no longer Rome but Córdoba, etc.

The Apocalypse, which had been interpreted as a prophecy of the end of the Roman persecutions, becomes the announcement of the Reconquest. It is a promise of delivery and punishment. Deciphering is easy for the masses who believe, and this book ends up acquiring, in Al-Andalus, more importance than the Gospels.

Theological Weapon

The Apocalypse, which the Arians refused to consider as a revealed book, and which focuses on the divinity of Christ, becomes VIII, in the text beacon of the resisting Christians. The Apocalypse is therefore a work of combat, a true theological weapon, against all those who did not see in Christ a divine person on the same plane as God the Father. The clergy of Asturias resumes the prescription of the IV Council of Toledo (633): under pain of excommunication, the Apocalypse must be considered as a canonical book; will be read at the "Mass" between Easter and Pentecost. Let us bear in mind that such an obligation only referred, of the entire Bible, to this one text.

James

The Commentary on the Apocalypse mentions that Santiago is the evangelizer of Hispania. Some historians even think that Beato is the author of the hymn O dei verbum, in which Saint Yago is described as patron saint from Spain.

At the beginning of the IX century "discovered" the tomb of Santiago in the "Campo de Estrella" (ie Compostela), which will become Santiago de Compostela. There the relics of the brother of Saint John the Evangelist would have been transported a century earlier, from Mérida, to steal them from the Muslim desecrators. Given that at the time the Apocalypse was assigned to Saint John, Beato perhaps wanted to also honor his brother Santiago the Major, and make the two sons of Zebedee the vectors of the values of martyred, resistant and glorious Spain.

Beato dies in 798, before the first mention of the tomb of the "Matamoros".

Mozarabic illumination

General information

In 1924, an exhibition of Spanish manuscripts with miniatures took place in Madrid ( Exposición de codices miniados españoles). And if the Blessed are especially studied, it is because they imposed new forms in the artistic field.

Already these X-century painters had practiced a technique of glacisGauguin, preceded by Matisse in the counter-curves, with its fluid contours, inventing the realistic expressivity of Picasso in the counter-curves Ladies in Avignon. And in fact, (...) even the art of the cubist portraits will not be seen again the face at the same time in front and profile, until the animal dismay of the painter of the Guernicawhich finds no great dazzling in these miniaturists who anticipated their millennium.Jacques Fontaine, Hispanic Pre-Romantic Art II, Mozarabic ArtCol. Zodiac, Pierre-Qui-Vire, 1977, p.305.

The fascination for these books thus has a doubly visionary dimension, as if the forms had, they too, prophesied... it has seemed to many that the Blesseds contained the very complexity of what they announced, offering unsurpassed answers to questions that were still stammering at the time of its rediscovery.

Of course, Mozarabic art was not born out of nowhere: its roots lie in the Visigothic, Carolingian, Arab currents, and even in Coptic art whose particular stylizations are well identifiable.

And if the specialists detect even more distant contributions, Mesopotamians, Sassanids, that does not mean that Mozarabic art is nothing more than the production of second-order artists, without great personality, diluting their lack of imagination in eclecticism. Far from being a simple illustration that would add nothing to the text, or even lead the reader astray, the Mozarabic coloring, often on the entire page and even on a double page, as Jacques Fontaine recognizes, led the soul from reading the text to the deepening of its meaning in a vision.

Among the most notable works (if the Blessed is excluded), it is necessary to cite the Bible illustrated in 920 by the deacon Juan in the monastery of Santa María and San Martín de Albares (said Bible of Juan de Albares, is preserved in the archives of the cathedral of León.

- "What a modern audacity in all the layouts!" Abstract of the figure, free graphics, significant decoration: Juan de Albares is the most outstandingly modern, the most excessively intrepid of the Mozarab illuminators. "(Jacques Fontaine, work cited , p. 350).

Looking at these images, we don't have the feeling that more than ten centuries separate us.

The Blessed

The reflections of a liturgy

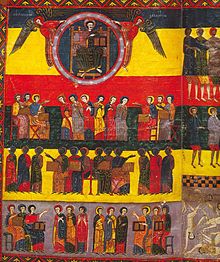

There remain about thirty illuminated manuscripts of the Commentary on the Apocalypse written by Beato in the Abbey of Santo Toribio de Liébana in 776, 784 and 786. Of these, twenty-five are complete, twenty-two have images, but only a dozen can be considered ancient. According to some hypotheses, the manuscript was decorated from the beginning, as suggested by the parts inserted in the text, which refer to an image. But none of these proto-Blesseds have been preserved.

The images shock even those who know the Apocalypse well. But it is not to underestimate the genius of the miniaturists, to recognize the relationship of many elements with the reality that surrounded them. If the decorations, the furniture, the attitudes seem to be pure products of the imagination, it is because the liturgy that gave rise to them is not familiar to us; that is why we attribute to invention what was included in the observation. Once again it is worth paying attention to the literary talent and precision of Jacques Fontaine:

There is perhaps to expect, from these illustrations, the visions of the Mozarab liturgy that we keep in the miniatures, in particular those of those of the Mozarab liturgies. Blessed. So here they feed each other things seen and visions. If the plights of the human liturgy already mean the imperfect and figurative realization of the great heavenly liturgy of the RevelationIt is evident, in the most proper sense - that of an immediate vision - that the painter Magius his students and his imitators have been unable to imagine what they saw only from what they saw. Hence so many altars with chalices, votive crowns suspended on these altars, which are like the onirical projection of what the Mozarabic monks saw in their churches and lived every day, but above all in the great feasts.Work cited, pp.47-48

.

This liturgy, these objects, these lights dazzled the Arabs themselves, like that Muslim chancellor who had attended a nocturnal ceremony in a church in Córdoba, as reported by his chronicler, also a Muslim:

He saw it covered with branches of myrtle and sumptuously adorned, while the sound of the bells resonated in his ear, and the brightness of the candles dazzled his eyes." He was fascinated in spite of him, in the sight of the majesty and the consecrated joy that radiated from this enclosure; then he remembered with admiration of the entrance of the priest and the other worshipers of Jesus Christ, all clothed with admirable ornaments; the aroma of the old wine that the ministers poured in his chalice and where the priest empapaba his pure lips; the modest behavior and the beauty of the children andin Jacques Fontaine, Work cited , p.49

Custom Manuscripts

Excluding some tragic visions of eternal damnation, some positions of despair, as Jacques Fontaine observes, "the dominant thing in these works is a serene contemplation" (cited Work, p. 361).

Humanity and even humor are present in the colophons. Thus, in the Beatus of Tábara, the painter Emeterio, in a drawing, represents the tower of the library and the scriptorium itself Adjacent, he represents himself and adds these words: "Ô torre de Tábara, tall stone tower, so tall that Emeterio remained seated, very bent over his task, for three months, and that all his limbs were crippled by the work of the pen. This book was finished on the 6th of the Kalends of August in the year 1008 of our era at the eighth hour." (in Jacques Fontaine, Work Cited, p. 361).

These colophons are nowhere as abundant as in Mozarabic works. The Beatus can thus be assigned and dated with great precision, which allows a serious study of the questions of stylistic affiliations. We know how Magius made the paintings of the Pierpont Morgan Library Beatus, that a painter named Ende helped her student Emeterio of hers in the realization of the Gerona Beatus.

Techniques and colors

The support is generally parchment, and also paper (present in the peninsula from the 11th century).

The text was written in brown (or turning brown) ink. Titles are often in red. This color was also used to draw the outline of page elements. The painters followed in this the recommendations of Isidoro de Sevilla extracted from the Etymologies: the contours are drawn first, then the figures are filled in with the help of colour.

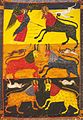

The colors of the paints are red (more or less dark), ocher, dark green, pink-mauve, dark blue, purple, orange, and above all very bright, very intense egg yellow, consubstantial to Mozarabic painting. Black is also used. Light blue and gray are rare.

"Hot" are the predominant ones: red, orange, yellow. Here again, the painters follow the teaching of Isidoro of Seville who makes an etymological approximation (well, for him, based on the essence of things) between the words color (Latin color) and heat (Latin heat): " The colors are named like this because they rise to their completion (perfection) by the heat of the fire or the sun" (Etymologies, XIX, chapter XVI).

Gold (metal) is very rare. It is present, or foreseen, in the Beatus of Gerona and in the Beatus of Urgell.

Some manuscripts are unfinished, which, on the other hand, tells us about the stages of their elaboration. In the Beatus of Urgell (ms 26, f°233) or in that of the Royal Academy of History of Madrid (ms 33, f°53), the drawing is only partially colored.

The colors are pure, without half measures, without mixtures, without transitions from one to another.

Whereas in the first Beatus they were quite dull, or, at least, discreet, the second style Beatuses (mid-century X ) draw attention due to the brilliance of their colors. It is undoubtedly due to the use, on a wax varnished background, of new binders, such as egg or honey that allow obtaining transparencies and bright, luminous tones.

If one excludes the refinements of tones of the Pierpont Library Beatus (and, of course, the unique exoticism of the Saint Sever Beatus), the colors are arranged rather in intense oppositions, and used to contribute to the unreality of the scenes.

- "Let's say here that the tones used by the Mozarab painters are rather not imitative, and, on the contrary, generally used for their own impact." This aspect of colour, in figurative painting, is the one that was considered normal, and even as fundamental, by Isidoro of Seville: "On the other hand, they say that something painted is fined;" since all painting is fined image, and not reality; (Mireille Mentré, Obra cited, p. 162).

Of course, when Isidoro de Sevilla speaks of truth, he understands it as conformity with sensible reality. But as we saw with the problem of space, the painters of the Beatus did not seek an adaptation to the world of perception. The reality they make known is of a spiritual nature.

The colors are neither mixed nor lowered. The modeling, the shadow, the lowering, only appear in the Saint-Sever Beatus.

In the Spanish Beatos, the vivacity of the colors, their contrasts, the very violence of some juxtapositions, strangely lead the gaze not to stop at a global perception, but towards the constitutive elements of the page.

Here too, as with the treatment of space, the painter's objective seems to be to distract the spirit from the temptations of the accidental to attract it to the essence of the story offered in aesthetic contemplation.

Forms, arrangements and meaning

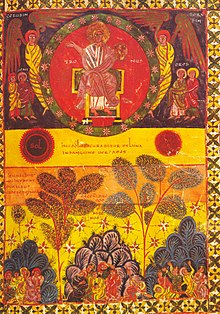

One of the originalities of many pages of the Beatus is the presentation of the scenes on a background of wide horizontal painted bands that do not correspond to any external reality. It is not about the sky, the water, the horizon or the effects of approaching or receding. There was talk of a "derealization" of space by color.

"As later with El Greco, painting here becomes a spiritual method," writes Jacques Fontaine (Obra Cited, p. 363). The sensible world is purified of its anecdotal elements only to make room for the fundamental part. It is about showing that something is happening without being distracted by describing the place where it happens. The protagonists of the apocalyptic drama further explore what is happening in their soul (or in that of the reader), with "this sullen fixity that sometimes reaches the point of ecstasy and excess", to pick up the Mireille Mentré's formula.

The shapes are geometric, and the schematization sometimes reaches the point of abstraction. Thus the representation of the mountains by overlapping circles. These conventions are common to several manuscripts.

However, the decorative never triumphs over the symbolic: despite the simplification of the forms, the multiplicity of viewing angles in the same scene, the images continue to be eminently and clearly the reference. Schematics and ornamentation never predominate over readability.

Some manuscripts have "tapestry-pages", complete pages generally located at the beginning of the book, where information about the scribe, the painter or the recipient of the manuscript is found, among geometric and labyrinthine motifs. These pages imitate the bindings (contemporaneous with the book, but also appear Coptic), and sometimes resemble Persian or Turkish rugs.

In the Saint-Sever Beatus, to which a special part will be reserved, there are tapestry-pages where the intertwining seems to be Irish-inspired.

View angles and conceptual reality

It is necessary to return again to the important question of viewing angles. There is no perspective in Mozarabic painting or, in particular, in the Beatus. In addition, the two-dimensionality of the figures leads to representing them simultaneously under several faces, which is also a particularity of Coptic art. But, while the cut and the three-quarters are present in the Coptic representations, the Mozarabic manuscripts reject everything that could outline a three-dimensionality. Not only can a figure be composed of a face and a profile, but the details of each of these two aspects of an element can be established in a seemingly inconsistent manner of face or profile.

The most typical example is the representation of the souls of martyrs under the altar in the fragment of Blessed preserved in Silos." The altar, on the upper part of the image, is seen face; this same altar, on the lower part, is seen from above; the heads of the martyrs, on the upper part of the illustration, are seen from above; the heads of the martyrs are placed completely parallel to the page; the birds are seen, symbolizing the souls, from below the profile; they are placed on the top of the altar, on the lower side.Mireille Mentré, Work cited, pp 156-157.

The Urgell Beatus presents a similar image.

Sometimes a page shows a city with the walls seen from the front and above what is inside the enclosure. What matters to the painter is to represent all the essential elements of a vision, as if the viewer were at the same level with each of them.

Let us observe for example the plague of the Apocalypse where the fourth angel who plays darkens the moon, the sun, the stars, as manifested in the Beatus of the Pierpont Morgan Library (ms 644, f° 138v): it is necessary, theoretically, to stand in front of the stars and then very exactly in front of the angel, and finally in front of the earth, for each one of these figures must be understood directly and independently." There is thus a plotted vision at optical level, but ordered at concept level.Mireille Mentré, Obra cited, p. 158.

The author of this thesis on Mozarabic painting highlights that what really matters for the artist is conceptual cohesion and not perceptual cohesion. Each element is in direct relationship with the viewer, but does not maintain a structural relationship with the other elements. The image is not the place where the sets of objects are organized to offer the representation of a real scene; it is the disposition of the elements of the story, taken one by one, that should affect us due to its symbolic dimension.

"Perceptive synthesis is not made in objects, nor in assemblies;" and even probably does not have to be made of the whole, in images of this type. The perspectives used and the relationships established between the motives and figures are included in the criteria, finally, that can hardly be given by perceptives - if we understand by perception the synthesis we make of the data offered in view. Classical arts offer a material that allows rebuilding this synthesis, or even making it more or less illusoryly for us. Mozarabic painting is not part of these preconceptions. The cohesion of the image works at the level, essentially, of concepts, rather than in tangible realities; figuration above all is a support for understanding and reflection, rather than a probable place for a real scene.Mireille Mentré, Obra cited, p. 159.

The Blessed thus offers an audacious reduction of the scenes destined to favor spiritual reading.

The figures should be read according to the order of thought and not according to the order of a sensitive reality included in a place, a time, a unique and synthesized space.Mireille Mentré, Work quoted, p. 154

Art, here, becomes auxiliary to the deep meaning of a text. The apocalyptic vision is not a simple work of art: it is tempting to say that the mystical journey in the Blessed is essential to complete and purify our intellection of the word of Saint John.

From models to school exercises

All talented artists are not necessarily creative geniuses. The latter were the ones who produced original works, not in the vulgar sense of the term, but in that they were the origin of other works and of new ways of posing and solving aesthetic problems. Thus, certain Blesseds come from a founding thought, while others are only sumptuous school exercises.

This is the case of the Beato painted by Facundo for Fernando I de León and the queen consort Sancha de León, and finished in 1047. The miniatures have no original composition. We love the work for its bright colors, due above all to a remarkable state of conservation, and also for the elegance of the forms. However, it is necessary to recognize that Facundo meticulously follows, in terms of structure, the miniatures of the Urgell Beatus made in La Rioja or León in the year 975.

It is enough to compare the f° 19 of Urgell (the Christ bearer of the Book of Life) with the f° 43 of Facundo; the double page 140v 141 of Urgell (Woman and the Dragon) with the double page 186v 187 of Facundo; the double page 198v 199 of Urgell (the New Jerusalem) with the double page 253v 254 of Facundo. We could list many more pages still.

Facundo is also largely inspired by the Valladolid Beatus, completed by the painter Oveco in 970. Compare f° 93 of the Valladolid Beatus and f° 135 by Facundo; f° 120 of the Blessed of Valladolid compared to f° 171 of Facundo.

Facundo is also greatly influenced by the art of Magius (Beatus de Pierpont, finished in 960), all these works present an evident affiliation with the Codex biblicus legionensis, a Mozarabic bible from 960 painted by Florentius and preserved in the collegiate church of San Isidoro de León.

Facundo does not invent. He softens the lines, gives more finesse to his characters and proposes images that seem more seductive to us. But seduction is not the end of art, and some specialists will say that his work indicates a loss of flavor in relation to the aesthetics of the previous Blesseds.

A separate manuscript: the Saint-Sever Beatus

We already mentioned this manuscript whose specificity is necessary to highlight. It is preserved in the National Library of France (acronym Ms Lat. 8878).

It is the only known Beatus copied in the Romanesque period north of the Pyrenees. It includes the Commentary on the Apocalypse by Beato de Liébana, as well as the Commentary on the book of Daniel by San Jerónimo. The lighting program is distributed as follows:

- The Evangelists and their symbols.

- The genealogy of Christ (here very detailed).

- The Commentary of the Apocalypse.

- The Commentary of Daniel's book.

In the 292 folios, there are 108 miniatures, 84 of which are historiated (including 73 full pages and 5 double pages). The pages measure 365 x 280 mm.

It was made during the 44-year term of Gregorio de Montaner (from 1028 to 1072), therefore around the middle of the century XI. We know the name of a scribe, who was perhaps also a painter: Stephanius Garsia. The stylistic differences incline to think that there are several scribes and painters. But despite that, the images present a certain unity:

- They are of French Romanesque style, and if some pages-tapices prove a foreign influence, it would be rather Irish.

- However, the structure of the images is that of the Mozarab manuscripts. Among others, the structural relation of the double pages can be indicated by presenting the 144,000 chosen at the Blessed of Urgell and Saint Sever, the altars at T, etc.

This character can be seen, for example, in the representation of the New Jerusalem: as in all Mozarabic manuscripts, it is made up of a square, but in Saint Sever, the arches are Romanesque, with a full curve, and not Visigothic with horseshoe arches.

The letter and the spirit

The artists of the Beatus wanted to avoid an excess of redundant images in relation to the text, stressed over the words, replacing them in our perception. The artists of the 10th and 11th centuries, we saw it, they solved the problem by unrealizing the scenes, renouncing all useless set elements in order not to immerse the reader's gaze in everything that would discard the spirit of the fundamental part. Then the miniatures are released, purified of everything that can be considered anecdotal.

The artist can also add data resulting from Beato's commentary to the figuration of a vision. This is what can be seen in the Beato of Osma (f° 117v) and in the Beato of Facundo (f° 187), where the Devil is shown chained in hell and where the Angels gather those swept away by the Dragon's tail. Here the miniature appropriates Beato's comment that, on the occasion of book XII of the Apocalypse, anticipates book XX where it is mentioned that he chained himself to Satan.

The painter's work can be even more complex when, in the same miniature, he proceeds to a bold synthesis of various passages. He must then renounce the verbatim transcription. If the 24 Elders (or Wise Men, or Old Men) run the risk, in a reduced space, of causing a commotion that would cover up other essential data... 12 are represented! It doesn't matter: we know there are 24, since the texts say so and other pages show them in full! The ranks are cleared up a bit, some wings are removed elsewhere, and thus there is room enough to offer an overview drawn from two chapters. This is what can be seen in the admirable miniature on f° 117v of Facundo's Beato:

"The great Theophany continues with this miniature from Beato de Facundo (folio 117 verso, format 300 x 245 mm., diameter of the circle 215 mm.) that unites two passages of the text in a single image (Apoc IV 2 and 6b-8a, as well as V 6a and 8) to constitute the vision of the mystical Lamb." But the illustrator takes liberties with the text. Thus the four Beings of the Tetramorphs, which symbolize the four Evangelists (each one carries a book) does not each carry six wings, but a single pair, covered with eyes; on the other hand, they are on top of a kind of disc inspired by the famous wheels of Yahweh's chariot, in Ezekiel (I 15), according to a very old formula that is frequent in the iconography of the Tetramorphs. As for the Twenty-four Wise Men, they are reduced to twelve only, who perform the actions described (Apoc. V 8): four of them "kneel down", four others "have zithers"; (always of the Arab type), and the last four have in their hand "golden cups full of perfumes". In the center, finally, the Lamb, bearer of the Asturian cross, is in possession of a reliquary that symbolizes the Ark of the Covenant. Above the circle is the open door to heaven, a horseshoe arch contains the divine throne (Apoc. IV 2) "with the one who sits on this throne".

The synthesis of passages IV-4 and V-2 of the Apocalypse is very frequent. It can even be found on folios 121v and 122 of the Beatus of Saint Sever.

Lighting and sculpture

The great French medieval art historian Émile Mâle believed he saw the influence of Blessed in the capitals of the portico-tower of Saint-Benoît-sur-Loire (formerly Fleury-sur-Loire), and Maria-Madalena Davy grants a certain credence to this thesis But Eliane Vergnolle, in her main work on Saint-Benoît-sur-Loire shows quite convincingly that the historiated capitals of the tower of Abbot Gauzlin, were inscribed in the Carolingian tradition - some even recall the shapes of the miniatures of the Apocalypse of Trier, or of the Commentary on the Apocalypse by Aymon de Auxerre (the latter manuscript preserved in the Bodleian Library in Oxford).

We also know that Gauzlin extended the influence of the Fleury abbey to Italy, from there he brought a painter named Nivard to represent scenes from the Apocalypse on the walls of the church -which confirms the Carolingian iconographic orientation, rather What a Mozarabic, from the decorations of the abbey. The question would be more prone to controversy regarding the second great building to which Émile Mâle refers: the Tympanum of Saint Peter of Moissac. Like so many others, Margarita Vidal determinedly follows the lesson of Émile Mâle and believes that this tympanum offers reliable indications of the presence of an illuminated manuscript of the Commentary on the Apocalypse by Beato de Liébana in the library of The abbey. However, regarding the subject of this article, reservations are imposed:

- For Émile Mâle, the most beautiful of the Beatos, and more susceptible to exert influence, is Saint Sever's on the Adoration, and if the master of the Moissac Tímpano has a debt, it cannot be towards a Mozárabe painter.

- In any case, Emile Mâle's argument remains somewhat dangerous. Indeed, it maintains that if some details of the eardrum differ too much from the images of the eardrum Beato of Saint Sever, it is because the sculptor only had under his eyes a copy that presented variants, but of which there is no trace left! In short, he states, without anything supporting this thesis, that a devoid sculptor of inventive genius drew his inspiration from a manuscript that no one would have heard of.

- It would be at least strange that a sculptor has taken as a model a manuscript present in the library, and recognized it as a main work, while no known book coming from the Moissac scriptorium denies a relationship with the Beatus of Saint Sever (not more than with others) Blessed).

- Finally, why want to make the sculptor a simple copist capable of making a model adaptation on a different support? To retake André de Malraux, the eardrum is not a sculpted lighting. In this respect, photography is wrong, as it allows to place side by side a miniature and a sculpture. These two arts differ in many points... even the recipients do not belong to the same world.

Nevertheless, it is necessary to recognize some disturbing stylistic analogies between the double page 121v-122 of the Blessed of Saint Sever] and the Moissac Tympanum. There is, for example, in both works the bold turn of the bull's head in adoring tension in the direction of Christ.

However, if there are some similarities between the Twenty-four Wise Men of the Blessed (same double page) and those of the tympanum (hairstyles, zithers, haircuts), the latter offer a joyous animation not without nobility, -while those of the Blessed they seem like a band of funny people raising their glasses during a tavern song: the majesty of Moissac owes nothing to the riot of Saint Sever... Which does not deprive the undeniable beauty of so many other pages of that same manuscript. As for the Mozarabic Blessed , they should not be despised because they do not serve as models for other arts. They do not have the breadth of their diffusion and their possible influence. And even if they did not have any posterity, they would still be, in our aesthetic perception, such grandiose monuments that, like the enigmatic statues on Easter Island, they have the power to make us dream of another universe.

Conclusion

For Hegel, philosophy is the highest activity of the spirit, since it translates into concepts what religion says in stories, which, themselves, had in words what art presented in images. Certainly, for him the truth becomes perceptible in beauty in a sensible way; However, the spirit only reconquers being in its entirety, understanding that Nature is nothing more than the spirit that exiles itself and that there is a consubstantiality of the real and the rational. Everything is understandable by the spirit because, basically, everything is spirit.

Examining Mozarabic painting upsets this hierarchy. Traveling through the pages of the Blesseds, we are not facing sensible realities that are still close to natural realities. We are in a world of images that speak better to the soul than words supporting the concepts, and that, on the contrary, through their abstraction facilitate access to the truth of the story, without thereby favoring a pure aesthetic seduction due to the preponderance of the ornamentation. As if the silent moment of ecstasy exploded in colors of fire, the ineffable meaning of the text finding itself crystallized in "surreal" shapes and colors.

The term illustration is absolutely not appropriate to name artistic productions that are full-fledged works of art. In the convent of San Marco in Florence, Fra Angelico does not illustrate the Gospels: at the same time that he gives us the beauty of his frescoes, he offers our intelligence the fruit of his meditation on the texts.

The Blesseds are not a useless paraphrase of the Apocalypse (or its commentary by the monk from Liébana): they are visions born of a vision, of new layers of truth added to the prophetic text. Thus, Beauty is nothing more than a stage on the road that leads to Truth: the fire of colors mixes in the brazier of words to launch new sheafs of meanings into our dazzled souls.

The main Blesseds

Among the 31 Blessed (some of which only fragments remain), it is necessary to distinguish:

- Beato de Cirueña. CenturyIX. Library of the Monastery of Santo Domingo de Silos. Frag. 4.

- Beato of the San Millán del Cogolla (valle del Ebro). 930. Madrid, Real Academia de la Historia. Ms. 33.

- Beato from San Millán. 950/ 955. Monastery of El Escorial. Royal Library of San Lorenzo. Ms. and II. 5..225 x 355 mm. 151 leaves. 52 illuminations.

- Beato Morgan (near Lion. 960. J. Pierpont Morgan Library, New York. Ms 644. 280 x 380 mm. 89 illuminations. Painted by Magius, archipintor.

- Beato de San Salvador de Tábara. 968 / 970. Madrid. National Historical Archive. Ms 1097 B (1240). Painted by Magius, finished after his death by his pupil Emeterius.

- Beato de Valcavado. 970. Valladolid. University Library. Ms. 433 (ex ms 390). 97 remaining illuminations. Painted by Oveco for Abbot Semporius.

- Beato from Rioja or León. 975. Cathedral of La Seo de Urgel. Archives. Ms. 26. 90 illuminations.

- Beato de Tábara. 975. Gerona Cathedral. Archives. Ms. 7. 260 x 400 mm. 280 leaves. 160 illuminations. Painted by Emeterius (a student of Magius) and by the painter Ende.

- Beato from San Millán. 2nd third of the centuryX Madrid. National Library. Ms. Vit. 14.1.

- Beato de Fernando I y doña Sancha 1047. Madrid. National Library. Ms. Vit. 14.2. In charge of Fernando I and Queen Sancha. 267 x 361 mm. 312 leaves. 98 illuminations. Painted by Facundo.

- Beato. 1086. Cathedral of El Burgo de Osma.. Cod. 1. 225 x 360 mm. 166 leaves. 71 illuminations. Write: Petrus. Artist: Martinus

- Beato de Saint-Sever of the Abbey of Saint-Sever (Landas). 1060 / 1070. Paris. National Library of France. Ms. Lat. 8878.

- Beato of the Holy Sunday of Silos. 1091 / 1109. London. British Library. Ms. Add. 11695.

- Beato Corsini (currently in Rome, Corsinian Library, Lincei Academy, 369 (4O.E.6)

- Beato de Lorvao, National Archive of the Torre do Tombo. Lisbon. CenturyXII. 1189.

- Beato de Turin, located in the Nazionale Library, Turin

- Beato de Manchester, currently at the John Rylands Library (Mánchester).

- Beato navarro, preserved in National Library, Paris. Acquired in 1366.

- Beato de San Andrés del Arroyo, currently in Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.

- Beato de San Pedro de Cárdenas, realized between 1175 and 1180. Archive of the Natural Archaeological Museum, Madrid

- Beato de Medina de Rioseco, fragment found in Mexico (centuryXIII)

The World Map of Beato de Liébana

Beato de Liébana, is internationally recognized by historians of geography and cartography. It is considered that his work greatly influenced this field for centuries with the type of Map of T in O

Contenido relacionado

Sergius III

The birth of Venus (Botticelli)

Mayan calendar