Battleship

A battleship is a heavy-tonnage, heavily armored, and armed warship with a main battery of large-caliber guns. Battleships are larger, better armed and armored than cruisers and destroyers. They were the largest warships in the fleets, representing the peak of a nation's naval power, between 1875 and World War II (1939-1945). Its purpose was to achieve maritime supremacy, but with the empowerment of air power and the development of guided missiles, its large guns ceased to be decisive for naval superiority and battleships fell into disuse.

Battleship design evolved to always be in the forefront with the incorporation and adaptation of technological advances. The term "ironclad" came into use in the 1880s to define a type of metal-plated armored warship, the ironclad, which is now known to naval historians as dreadnoughts pre-dreadnought. In 1906 the launching of the British battleship HMS Dreadnought started a revolution in the design of this type of ships, and the battleships inspired by this ship began to be called dreadnoughts.

Battleships were a symbol of naval dominance and national sentiment, and for decades also an important factor in both diplomacy and military strategy. By the turn of the century 19th century and early 20th century a naval arms race took place with the construction of battleships, exacerbated by the Dreadnought revolution, which would end up being one of the Causes of World War I. In the course of this conflict, the Battle of Jutland was the largest clash of battle fleets made up of battleships. The naval treaties of the 1920s and 1930s limited the number of battleships but did not end the evolution in their design. The Axis and Allied powers fielded both vintage and newly built battleships during World War II.

The worth of battleships has been questioned, even in their heyday. Despite the immense resources put into the creation of battleships and their enormous firepower and armor, there was very little fighting between them and they proved becoming increasingly vulnerable to smaller, cheaper ships and weapons: first torpedoes and sea mines, and later aircraft and guided missiles. The increasing distance of naval engagements led to aircraft carriers replacing battleships as primary ships in combat during World War II, and the last battleship, the British HMS Vanguard, was launched in 1944. The United States Navy maintained several battleships in service during the Cold War for gunnery support roles and the last of these, the USS Wisconsin and USS Missouri, were decommissioned in 1991 and 1992, respectively.

Ships of the Line

The ships of the line were large unarmored wooden sailing ships that mounted batteries of up to 120 smooth-bore cannons and carronades. They were the product of the gradual evolution of a basic design dating back to the 15th century, and apart from growing in size they had changed a lot. little between the adoption of battle line tactics in the early 17th century and the 1830s. The line could sink any wooden ship by firing broadsides from its many guns, smashing its hull and masts and killing its crew. However, the guns had a very limited range, only a few hundred meters, so their battle tactics were heavily dependent on the wind.

The first major change in the concept of the ship of the line was the introduction of the steam engine as an auxiliary propulsion system. Steam engines were gradually introduced into navies throughout the first half of the 19th century, initially on small boats and later in frigates. The French Navy introduced steam to the battle line with the 90-gun Napoleon in 1850, the first steam powered warship. The Napoleon was armed as a conventional ship of the line, but her steam engines gave her a speed of 12 knots (22 km/h) regardless of the wind, a potentially decisive advantage in naval combat. The introduction of steam accelerated the growth in size of warships. France and the United Kingdom were the only countries to create fleets of wooden warships with propellers, while other countries only put a few ships of this type into service, such as Russia, Turkey or Sweden.

Armored Ships

The addition of steam engines was just one of the technological advances that revolutionized warship design in the 19th century . The ship of the line was surpassed by the ironclad, a type of steam-powered ship, protected by metal armor and armed with cannons that fired high-explosive howitzers.

Explosive Shells

Cannons that fired explosive or incendiary shells were a major threat to wooden ships. These weapons became widespread after the introduction of 203 mm guns as part of the standard ship-of-the-line armament of the French and American navies in 1841. In the Crimean War (1853-1856) six ships-of-the-line and two frigates of the Russian Black Sea Fleet destroyed seven Turkish frigates and two corvettes with explosive shells at the Battle of Sinope (1853). Later in the same conflict, in 1855, French ironclad floating batteries used similar weapons against the defenses at the Battle of Kinburn.

However, wooden-hulled ships withstood the impact of these shells relatively well, as seen at the Battle of Lissa (1866), in which the modern double-decked Austrian steamer Kaiser rammed an Italian ironclad in the course of a confused engagement and received eighty hits, most of them from shells but at least one from a 136 kg howitzer at very close range. Despite losing her bowsprit and her foresail and being set on fire, the next day she was once again ready for action.

Hull and Iron Armor

The development of high-explosive howitzers made it necessary to use metal armor on warships. In 1859 France launched La Gloire, the first ocean-going ironclad warship. She had a ship of the line profile and a single deck to reduce her displacement. Despite being made of wood and relying on its sails for most voyages, La Gloire was fitted with propellers and its wooden hull was covered in thick iron plate armor. ship forced the British Royal Navy to innovate, eager to prevent France from taking technological advantage.

Just fourteen months after La Gloire the British launched the superiorly armed frigate Warrior, after which both nations embarked on a program of building new ironclads and of conversion of ships of the line with propellers into armored frigates. Within two years Italy, Austria, Spain and Russia had ordered the construction of ironclad warships, and by the time the famous combat between the USS Monitor and the CSS Virginia at the Battle of Hampton Roads in 1862 at least eight countries had ironclad ships.

Navies experimented with the arrangement of guns in turrets (like the USS Monitor), in central batteries and on barbettes, or with the ram as the main weapon. Steam engines continued to evolve and masts were gradually removed from warship design. By the mid-1870s, steel was already being used as a construction material along with iron and wood. The Redoutable of the French navy, laid down in 1873 and launched in 1876, was a ship with a central battery and barbette that became the first military ship in the world to use steel as the main material of construction.

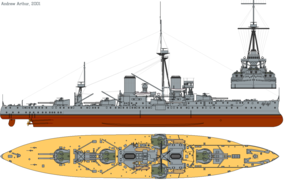

Pre-dreadnought battleships

The term "dreadnought" was officially adopted by the British Royal Navy in the reclassification of 1892. In that decade battleship design was taking on similar characteristics, those of the type known today as "pre-dreadnought battleships". They were ships without sails, heavily armored and with heterogeneous batteries of guns in turrets. The typical class of battleships of the pre-dreadnought era displaced between 15,000 and 17,000 tons, had a speed of 16 knots (30 km/h), and carried a main armament of four 305mm guns. in two turrets, one forward and one aft, and a secondary battery of various calibers arranged amidships, around the superstructure.

Slow-firing 305mm guns were the primary weapons for armor-versus-armor combat. The secondary and intermediate batteries had two roles. Against large ships a barrage of fire from the fast secondary weapons was used to deal damage to superstructures and distract enemy gunners, useful against smaller ships like cruisers. The smaller guns, under 5.5 kg, were reserved to protect the battleship from the threat of torpedo attacks from destroyers and torpedo boats.

The beginning of the pre-dreadnought era coincided with the reassertion of the naval power of the United Kingdom, which had long before dominated the seas. Expensive naval projects were criticized by British political leaders of all stripes, but in 1888 fear of war with France and Russian rearmament gave new impetus to shipbuilding on the islands. The British Naval Defense Act of 1889 led to the commissioning of a new fleet, including eight new battleships. The principle was established that the British navy should be more powerful than the next two naval powers combined, a policy intended to stop French and Russian battleship construction. Despite this, these two countries expanded their fleets with more and better battleships in the 1890s.

In the last years of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century the escalation in the construction of battleships led to a race of naval armaments between the United Kingdom and Germany. German naval laws pushed through by Alfred von Tirpitz in 1890 and 1898 authorized a fleet of thirty-eight battleships, a very serious threat to the naval balance of power. The United Kingdom responded with more battleships, but towards the end of the era < i>pre-dreadnought British supremacy had weakened considerably. In 1883 the United Kingdom had thirty-eight battleships, twice as many as France and almost as many as the rest of the world, but by 1897 its dominance was much less due to competition with France, Germany and Russia, as well as the development of fleets. of pre-dreadnought battleships in Italy, the United States, and Japan. Turkey, Spain, Sweden, Denmark, Norway, the Netherlands, Chile, and Brazil had second-rate fleets consisting of armored cruisers, ships of coastal defense or monitors.

The pre-dreadnoughts continued the technical innovations of the ironclads and improved turrets, armor plating and steam engines, as well as introducing torpedo tubes. Some designs, such as the US Kearsarge and Virginia classes, experimented with intermediate batteries consisting entirely of 203 mm guns superimposed on the main 305 mm. The results were very poor, as the effects of recoil and explosions from the primary weapons rendered the 203mm batteries unusable, added to the inability to use the primary and secondary weapons against different targets, something that caused serious tactical limitations.. The weight savings achieved with these designs, a key reason for their implementation, did not make up for the difficulty of putting them into practice.

Dreadnought era

In 1906 the British Royal Navy launched the revolutionary HMS Dreadnought, whose construction and characteristics were promoted by Admiral John Arbuthnot Fisher. The origin of the term Dreadnought comes from joining the English words dread, "fear", and nought, "nothing" (which can be literally translated as "nothing to be afraid of"). This ship rendered all existing battleships obsolete by combining a uniform battery of ten 305mm guns with powerful armor protection and unprecedented speed, and forced navies around the world to re-evaluate their battleship-building programs..

Although the Imperial Japanese Navy had already launched in 1904 a battleship with a main battery of powerful guns, the Satsuma, and this concept of equipping the ships with numerous high-powered guns had been considered. several years, it had not yet been put to the test in combat. The Dreadnought spurred a new naval arms race around the world and especially between the United Kingdom and Germany as this new class of battleships became a key element of national power.

Such a success of popularity means that the use of the term dreadnought is often used before the Spanish name for this type of ship: «monocalibre battleships». Technical development advanced rapidly in the dreadnought era and was seen in all aspects of warships: artillery, armor and propulsion. Ten years after the Dreadnought was launched, much more powerful ships were being built, the super-dreadnoughts.

Origin

In the early years of the 20th century various navies around the world experimented with the idea of a new type of battleship endowed with a uniform armament of large-caliber cannons. Admiral Vittorio Cuniberti, head of naval architecture for the Italian navy, had already outlined the concept of a battleship with a uniform battery of powerful guns in 1903. As the Regia Marina did not put his ideas into practice, he wrote an article in the publication book Jane's Fighting Ships annual proposing the "ideal" future British battleship: a large 17,000-tonne armored ship, armed with a single caliber main battery (twelve 305mm guns), 300mm belt armor and capable to sail at 24 knots.

The Russo-Japanese War provided the operational experience to test this uniform battery concept. In the naval battles of the Yellow Sea (1904) and Tsushima (1905) pre-dreadnought battleships exchanged salutes at ranges of between seven and seven kilometers, out of range of their secondary batteries. Although these engagements demonstrated the importance of the 305mm guns over their smaller caliber counterparts, some historians hold the view that the secondary batteries are just as important as the larger guns.

The first two battleships with a single battery of large-calibre guns were laid down in Japan as part of the 1903-04 Program, equipped with eight 305mm guns. However, the designs called for armor that was considered too thin and required substantial redesign. The financial pressure of the Russo-Japanese War and the few 305 mm guns available, as these had to be imported from the United Kingdom, forced that these ships were launched with a mixed battery of 254 and 305 mm guns. This 1903-04 design also retained the traditional triple expansion steam engines.

Already in 1904 John Arbuthnot Fisher, First Lord of the Admiralty of the British Royal Navy, was convinced of the need for faster and more powerful ships with unique large-caliber weapons, and what happened in Tsushima convinced him of the need to standardize the 305 mm guns. Fisher was concerned about submarines and torpedo-equipped destroyers, which then threatened to outrange the guns of battleships, and this made it imperative to increase the speed of the main ships. The preferred option To this British admiral was a concept created by him, the battlecruiser: lightly armored but heavily armed with eight 305 mm guns and capable of cruising at 25 knots (46 km/h) with its steam turbines.

The British HMS Dreadnought was the embodiment of the new battleship concept and the test bed of revolutionary technology. She designed in January 1905, laid down in October of that year and completed in 1906, she carried ten 305 mm guns, 279 mm armored belt and was the first large ship to be powered by steam turbines. It mounted its cannons in five turrets, three in the center line (two towards the stern and one towards the bow) and another two on both sides in the center of the ship, which gave this battleship at the time of its launching a power of fire twice as great as any other ship. She kept several 76mm rapid-firing guns for use against torpedo boats and destroyers. Her armor was thick enough to go head-to-head with any other ship and emerge victorious.

- HMS Dreadnought (1906)

The Dreadnought was to have been followed by three Invincible-class battlecruisers, but construction was delayed to incorporate the lessons learned from the Dreadnought into their designs. . Although Fisher intended this to be the last battleship in the British Royal Navy, her design was so successful that she lost support for her plan to convert the entire navy into a fleet of battlecruisers. Although there were some problems with the Dreadnought (the blown-out turrets on the sides had a limited firing radius, pressed and damaged the hull when a full salvo was fired, and the thickest part of the armored belt was under the water with the ship fully loaded), the British Royal Navy promptly commissioned six other ships of similar design of the Bellerophon and St. Vincent class.

Arms Race

In 1897, before the Dreadnought revolution, the British Royal Navy had sixty-two battleships in service or under construction, twenty-six more than France and fifty more than Germany. In 1906 the navy The British took a giant step in the field of battleships, but began an arms race with very important strategic consequences. All the great naval powers vied to have their own dreadnoughts, for the possession of modern battleships was not only vital to a maritime power, but also, like nuclear weapons today, represented the status of a nation in the world. Germany, France, Russia, Italy, Austria, Japan, and the United States began construction programs for dreadnoughts and second-rate powers such as Turkey, Argentina, Brazil, and Chile commissioned the creation this type of battleships to British and American shipyards.

World War I

World War I was a disappointment for the large dreadnought battleship fleets because there was no decisive clash between modern battle fleets like at Tsushima. The intervention of battleships was marginal, since the great combats of the global conflagration, in France and Russia, were on land, and the so-called Atlantic campaign was an unequal fight between the German U-boats submarines and the British merchant ships.

Thanks to geographical factors, the British Royal Navy was able to keep the already powerful German High Seas Fleet blocked in the North Sea, since the straits and channels that led to the Atlantic were closed by British forces. Both parties They were aware of the numerical superiority of the British dreadnought battleships, so a major battle between the two fleets would result in victory for the British. For this reason, the German strategy was to try to provoke combat favorable to their situation: either force the Grand Fleet to fight alone or attract the British to the German coasts, where the minefields, torpedo boats and German submarines could balance the battle. scale.

In the first two years of the world war there were only minor skirmishes between battlecruisers, the battles of Heligoland Bay (1914) and Dogger Bank (1915), as well as some German attacks on British coasts. However, on May 31, 1916, a new German attempt to attract some units of the British navy ended in a major clash between the two fleets in the Battle of Jutland. After several hours of combat in which the British lost more ships and men, the German fleet had to withdraw before the evident numerical superiority of its contender and its commanders came to the conclusion that they would not face the British again in a battle of fleet against fleet.

In the rest of the battle theaters there were no major decisive combats, since in the Black Sea the struggle between the Russian and Turkish battleships did not go beyond skirmishes. In the Baltic Sea, actions were limited to attacks on merchant convoys and the laying of minefields, and the only significant battle between squadrons of battleships was the Battle of Muhu Strait, in which the Russians lost a battleship. The Adriatic Sea was in a sense a mirror of the North Sea: the Austro-Hungarian fleet of dreadnought battleships remained bottled up by the Franco-British blockade. Finally, in the Mediterranean, the most notable action carried out by battleships was the amphibious assault on Gallipoli.

This war exposed the vulnerability of battleships to cheaper units. In September 1914 the potential threat to large shipping posed by German U-boats was confirmed by the successful attacks on British cruisers, the case of the sinking of three British armored cruisers by the submarine U-9 in less than an hour. Sea mines also proved their danger a month later, when the new British super-dreadnought battleship Audacious struck one and sank. By the end of October the British had changed their strategies and tactics in the North Sea with the intention of reducing the risk of U-boat attacks. The German plan in the Battle of Jutland was based on took part in U-boat attacks on British units, and the German withdrawal in the face of increased enemy firepower was successful as cruisers and destroyers closed on the British battleships and forced them away to avoid the torpedoes. The danger of U-boat attacks on battleships and the casualties suffered on cruisers raised concerns in the British Royal Navy about the vulnerability of battleships.

For its part, the German High Seas Fleet decided not to undertake offensive actions against the British without the assistance of submarines, and once these were required to increase attacks on commerce, the fleet had to remain in port for as long as possible. remainder of the war. Other scenarios also demonstrated the effectiveness of smaller units in damaging or destroying battleships: the Austro-Hungarian navy's SMS Szent István was sunk by Italian torpedo boats in June 1918 and her sister ship, the SMS Viribus Unitis, was sunk by divers. Allied capital ships lost at Gallipoli were sunk by mines and torpedoes, while the Turkish pre-dreadnought Messudieh was captured in the Dardanelles Straits by a British submarine..

Interwar Period

Germany had no battleships for many years. The armistice with Germany signed after the end of World War I required that its entire High Seas Fleet be disarmed and interned in a neutral port. Faced with the difficulty of finding such a neutral port, the ships passed into British custody and were taken to the anchorage of Scapa Flow, in the Orkney Islands. Although the Treaty of Versailles stipulated that the ships had to be handed over to the British, most of them were scuttled at Scapa Flow by their own crews on June 21, 1919, shortly before Germany signed the peace treaty.. The treaty also limited the size of the German navy and prevented it from building or owning any large warships.

In the interwar period, battleships were subject to strict international limitations designed to prevent another costly arms race. Although the victors of the war were not bound by any treaty, most of the great maritime powers remained paralyzed after the conflagration. Faced with the prospect of a naval arms race against the United Kingdom and Japan, which would also have led to a possible war in the Pacific Ocean, the United States was prepared to conclude the Washington Naval Treaty of 1922. This treaty limited the number and the size of the battleships that major nations could own and required the UK to accept parity with the US and abandon its alliance with Japan. The Washington treaty was followed by other naval treaties, such as the First Geneva Naval Conference (1927).), the First London Naval Treaty (1930), the Second Geneva Naval Conference (1932) and finally the Second London Naval Treaty (1936), all intended to set limits on the size of capital ships. These agreements effectively became obsolete on 1 September 1939 with the outbreak of World War II, but the ship classification they had agreed to remained in effect.

The treaties also inhibited development by limiting the maximum displacement of ships, so projects like the British N3-class battleships, the first of the American South Dakota-class, and the Japanese Kii-class (all of which tended to be more bigger, better armed and armored) never made it past the drawing board. The ships that were launched during this period were known as "treaty battleships". Treaty limits led to fewer battleships being launched in the two decades from one war to the next (1919–1939) than from 1905 to 1914.

Rise of Air Power

As early as 1914, British Admiral Percy Scott predicted that battleships would lose all relevance to military aviation. By the end of World War I aircraft had successfully adopted the torpedo as a weapon, and in 1921 General Italian and air theorist Giulio Douhet completed an influential treatise on strategic bombing entitled The Air Command, in which he envisioned the dominance of air power over naval units.

In the 1920s, General Billy Mitchell of the United States Army Air Corps, believing that the air force had rendered all the world's navies obsolete, told the US Congress that "you can build and operate a thousand bomber planes for the price of a battleship" and that a squadron of such bombers could sink a battleship, making the most efficient use of government funds. This angered the US Navy, despite whereupon Mitchell was allowed to conduct a series of careful tests with Navy and Marine Corps bombers. In 1921 he bombarded and sank numerous ships, including the "unsinkable" German World War I battleship Ostfriesland and the American pre-dreadnought Alabama .

Although Mitchell had required "wartime conditions," the ships he sank were outdated, immobile, undefended, and out of damage control. In addition, the sinking of the Ostfriesland was accompanied by the violation of an agreement that would have allowed navy engineers to examine the effects of various munitions, as Mitchell's airmen disregarded the agreement and sank the ship in a matter of minutes in a coordinated attack. Mitchell then declared in the face of newspaper headlines: "No surface ship can exist where it can be attacked by air forces operating from land bases." Although far from conclusive, Mitchell's tests were relevant in that he put battleship advocates behind naval aviation. Rear Admiral William A. Moffett used public opinion against Mitchell to advance expansion of the nascent program. of aircraft carriers of the US Navy.

Reset

The navies of the UK, US, and Empire of Japan extensively expanded and modernized their World War I-era battleships during the 1930s. Among the new features were increased height and stability of the rangefinder towers (for fire control), more armor (especially on the turrets) and additional anti-aircraft weapons. Some British ships received a large block-shaped superstructure, nicknamed "Queen Anne's Castle", in the case of Queen Elizabeth and Warspite, and which was also used in the conning towers of the King George V-class fast battleships. they added anti-torpedo bulges both to improve buoyancy and counteract the increased weight and to provide underwater protection against mines and torpedoes. The Japanese rebuilt all of their battleships and battlecruisers with distinctive pagoda-shaped structures, and Hiei was fitted with a more modern turret that would influence the newer Yamato-class battleships. Bulges and a set of steel tubes were also added to improve underwater and vertical protection at the waterline. In the United States they experimented with cage masts and later with tripod masts, although after the attack on Pearl Harbor some of the most damaged ships, such as the West Virginia and the California, were rebuilt from scratch. similar fashion to her Iowa class contemporaries with the tower masts. Effective beyond visual contact, in the dark and in bad weather, radar was introduced as a supplement to fire control.

Even with the threat of war again in the late 1930s, battleship building did not reach the importance it had in the years before the first global conflict. The strategic position had changed and the construction pattern imposed by the naval treaties led to the reduction of the construction capacity of shipyards around the world.

In Germany the ambitious Plan Z of naval rearmament was abandoned in favor of a submarine warfare strategy supplemented by the use of battlecruisers and Bismarck-class battleships as privateers of commerce. In the United Kingdom the most pressing need was for air defense and convoy escort to safeguard the population from bombing and starvation, and plans for naval rearmament included the construction of five King George V-class battleships. It was in the Mediterranean where navies were most committed to battleship warfare. France planned to build six battleships of the Dunkerque and Richelieu classes, and Italy two Littorio-class ships. No military navy chose to build aircraft carriers, and the US Navy only allocated limited funds to the South Dakota class. Japan also gave priority to aircraft carriers, though otherwise began work on the huge Yamato-class battleships, the third of which, Shinano, was converted to an aircraft carrier and the fourth cancelled.

At the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War the Spanish navy had only two dreadnought battleships, the España and the Jaime I. The España, originally named Alfonso XIII, was then in reserve at the Ferrol naval base and fell into the hands of the Nationalists in July 1936. The crew of the Jaime I killed its officers, mutinied and He joined the Republican Army. With this, each side of the war had a battleship, although the Republican navy in general lacked experienced officers. The Spanish battleships were limited mainly to blockading each other, escorting convoys and conducting coastal bombardments, and were rarely involved in combat against other surface units. In April 1937 España collided with a sea mine laid by friendly forces and sank with little loss of life. In May 1937 the Jaime I was damaged by nationalist air raids, and she was forced to return to port to be repaired, where she received new hits from bombs dropped by planes. It was therefore decided to tow it to a safer port, but during the journey the battleship suffered an internal explosion that killed 300 people and caused the total loss of it. Several German and Italian capital ships participated in the non-intervention blockade of the civil war. On May 29, 1937, two Republican planes bombed the German pocket battleship Deutschland in Ibiza, causing serious damage and numerous deaths. Her sister ship Admiral Scheer retaliated by bombarding the port of Almería, where she caused extensive damage. The so-called Deutschland incident spelled the end of Italian and German support for non-intervention.

World War II

The German battleship Schleswig-Holstein, an obsolete pre-dreadnought, fired the first shots of World War II in the early morning bombardment of the Polish fortress of Westerplatte on 1 September 1939 and the signing of the surrender of the Empire of Japan in said conflict occurred aboard the American battleship Missouri. Between these two events it had become very clear that aircraft carriers were the new main ships of the fleets and that battleships had been relegated to a secondary role.

Battleships played important roles in major engagements in the Atlantic, Pacific, and Mediterranean theaters of war. In the Atlantic the Germans used their battleships as lone privateers for trade, while fighting between warships was of little strategic importance. The battle of the Atlantic was fought between destroyers or frigates and submarines, and most of the decisive engagements between the fleets in the Pacific were determined by the carriers.

In the first year of the war, armored ships defied the prediction that aircraft would dominate naval warfare. The German battleships Scharnhorst and Gneisenau surprised and sank the British aircraft carrier Glorious off the western coast of Norway in June 1940, however the last time a fleet carrier had been sunk by surface artillery. In the attack on Mers el-Kebir in July 1940, British battleships opened fire with their main guns on French battleships loyal to the Vichy government anchored in the port of Mazalquivir, Algeria, and then pursued French ships with aircraft carriers. they managed to flee.

The remainder of the war saw many demonstrations of the carrier's maturity as a strategic naval weapon and its potential against battleships. The British air raid on the Italian naval base at Taranto sank one battleship and damaged two more, and the same Swordfish torpedo planes that carried out this action were instrumental in hunting down and sinking the German privateer battleship Bismarck.

On December 7, 1941, the Empire of Japan launched a surprise attack on the U.S. naval base at Pearl Harbor in the Pacific archipelago of Hawaii. In a very short time five of the eight American battleships present in the port were sunk and the rest damaged. However, the aircraft carriers of the American fleet were at sea and avoided detection, and it was these ships that later took up the fighting and turned the tide of the war in the Pacific. The sinking of the British battleship Prince of Wales and its escort, the battlecruiser Repulse, by Japanese bombers and torpedo bombers on 10 December 1941 demonstrated the vulnerability of battleships to air forces while at sea without sufficient cover. aerial, finally proving the argument made by Mitchell in 1921.

In many of the crucial early battles in the Pacific, such as the Coral Sea and Midway, battleships were absent or overshadowed by the carrier strategy of launching waves of aircraft to attack hundreds of miles away. In the later battles in the Pacific, battleships primarily carried out shore bombardments in support of amphibious landings and also provided anti-aircraft defense as carrier escorts. Even the largest and most powerful battleships ever built, the Japanese Yamato-class, armed with nine 460mm guns and designed as the primary strategic weapon, never had the opportunity to demonstrate their potential in a decisive battle, as featured in the Japanese plans. before the war.

- Yamato (1941)

The last battleship engagement in history was the Battle of Surigao Strait on October 25, 1944, in which a group of technically and numerically superior American battleships destroyed a group of Japanese battleships with their gunfire after that these had been devastated by the attack of torpedoes launched from destroyers. All but one of the American battleships present in this engagement had been sunk at Pearl Harbor and then raised and repaired. When the Mississippi fired its final salvo that day it was the last attack by a battleship against another warship, and was unknowingly "firing a funeral salute to an era of naval warfare drawing to a close". About six months then the powerful Japanese battleship Yamato was sent on its last suicidal mission against US forces and sunk by a massive airstrike launched from US aircraft carriers.

Cold War

After the end of World War II, many navies retained their battleships, although they were no longer strategically dominant military assets. In fact, it soon became clear that the high cost of its construction and maintenance was no longer worth it, so after the world conflict only one new battleship was put into service, the British HMS Vanguard in 1946. During the war it had remained demonstrated that battleship vs. battleship combat, such as in Leyte Gulf or the sinking of the Hood, was the exception rather than the rule, and that the role of dogfights would further increase, making big gun weaponry irrelevant. The armor of the battleships also failed against nuclear attacks, as the Soviet Kildin-class destroyers and Whiskey-class submarines could fire tactical missiles with a range of 100 km or more. By the late 1950s many minor types of ships that had previously offered no significant opposition were now capable of taking out powerful battleships.

The remaining battleships found varied roles. The USS Arkansas and the Nagato were sunk during the nuclear tests of Operation Crossroads in 1946. Both ships proved resistant to surface nuclear explosions but vulnerable to underwater ones. The Italian Giulio Cesare was captured by the Soviets, who repaired it and renamed it Novorossiysk, but ended up sunk on October 29, 1955 in the Black Sea after colliding with a marine mine planted by the Germans. The two Andrea Doria-class battleships were scrapped in 1956, the same fate as the French Lorraine, in 1954, Richelieu, in 1968, and Jean Bart, in 1970. The four surviving British King George V-class ships were scrapped in 1957, and Vanguard in 1960. The rest of the British battleships had been sold or scrapped as early as 1949. Soviet Petropavlovsk was also scrapped in 1953, and Sevastopol and the Oktyabrskaya Revolutsiya in 1957. The Brazilian Minas Gerais was scrapped at Genoa in 1953, and her sister ship São Paulo sank in the Atlantic in 1951 during a storm when he was traveling to Italy to face the same fate.

Argentina kept its two Rivadavia-class battleships ARA Rivadavia and ARA Moreno until 1956 and Chile kept Almirante Latorre (ex HMS Canada) until 1959. The Turkish battlecruiser Yavuz, former German Goeben, was scrapped in 1976 after her sale to return to Germany was rejected. Sweden had several small battleships for coastal defense, one of which, the Gustav V, survived until 1970. The Soviets disassembled several incomplete battleships in the 1950s when plans to build several U-class battlecruisers Stalingrad was abandoned after Stalin's death. Three old German battleships ended in the same way: Hessen was captured by the Soviet Union, renamed Tsel and scrapped in 1960, Schleswig-Holstein was given the Russian name Borodino and used as a target ship until the 1960s, the same fate as the Schlesien, scrapped between 1952 and 1957.

The US Iowa-class battleships earned a new life in the US Navy as gunnery support ships, for with the help of radar and computer-controlled fire their howitzers could be directed with pinpoint precision to their target. The United States put the four Iowa class back into service for the Korean War and the New Jersey for the Vietnam War. The latter battleship was used primarily for coastal bombardment and fired 6,000 shells from her 406 mm guns and some 14,000 from her 127 mm guns during her front line service, seven times more than she fired in the Second World War. World War.

As part of US Secretary of the Navy John Lehman's effort to build a 600-ship navy in the 1980s, and in response to the commissioning of the Soviet battlecruiser Kirov , the United States reactivated all four Iowa-class battleships. The battleships served at various times as support ships in carrier battle groups and led their own battle groups. All were modernized to launch Tomahawk missiles, a weapon that the New Jersey used to bomb Lebanon in 1983 and 1984, while the Missouri and Wisconsin opened fire with their 406 mm batteries against ground targets and missiles. enemies during Operation Desert Storm in 1991. Wisconsin served as the Tomahawk strike command ship for the Persian Gulf and directed the sequence of launches that marked the onset of Desert Storm, in which he fired a total of twenty-four Tomahawks in the first two days of the campaign. In this mission the main threat to the battleships were the Iraqi surface-to-surface missiles based on the coast, as the Missouri was hit by two Silkworm missiles, in addition to one close by and another that was intercepted by the British destroyer HMS Gloucester.

All four Iowa-classes were decommissioned in the early 1990s, making them the last battleships in active service. Iowa and Wisconsin were maintained until 2006 in order to quickly enter service as gunnery support ships, pending the development of a superior ship for this role. However, the US Marine Corps believes that the current naval gun support and missile program will not be able to provide adequate fire support for amphibious assault or land operations.

Currently

With the retirement of the last US Iowa-class ships, no battleships are currently in service with any navy in the world. However, several are preserved as museum ships, both afloat and in dry dock. Most are in the United States: USS Massachusetts, North Carolina, Alabama, Iowa, New Jersey, Missouri, Wisconsin, and Texas. Missouri and New Jersey are now museum ships at Pearl Harbor and Camden, respectively. Wisconsin was removed from the US Navy Register of Ships in 2006 and is now preserved as a museum in Norfolk, Virginia, and Texas, the first to be converted to a museum, is at the San Jacinto Historic Site in La Porte (Texas). The North Carolina can be visited in Wilmington and the Alabama in Mobile. The only 20th century lowercase non-US battleship that you can visit is the Japanese pre-dreadnought Mikasa, preserved in Yokosuka.

Strategy and doctrine

Doctrine

Battleships were the embodiment of sea power. For the American naval strategist Alfred Thayer Mahan and his followers, a strong navy was vital to a nation's success, and control of the seas essential to force projection in foreign lands. Mahan's theory, proposed in the 1890 published book The Influence of Sea Power upon History, 1660–1783, dictated that the role of the ironclad was to sweep the enemy off the seas. While escorting, blockading, and privateering trade was to be the task of cruisers and smaller ships, the presence of the battleship was a potential threat to a convoy escorted by any type of ship other than a capital ship.

Mahan was highly influential in naval and political circles in the battleship era, advocating the creation of large fleets with the most powerful battleships possible. Mahan's work was developed in the late 1880s and a decade later it had a great international impact because it was adopted by several major navies, such as the British, American, German, and Japanese. The weight of Mahan's opinion was important in the development of the naval arms race led by battleships and equally decisive in the agreement of the great powers to limit the number of battleships in the interwar period.

The simple possession and existence of battleships could condition a superior enemy in resources and tip the balance of a conflict even without engaging in combat, as it suggested that an inferior naval power with a fleet of battleships could have a significant strategic impact.

Tactics

While the role of battleships in both world wars reflected Mahan's doctrines, the details of their military deployment were more complex. Unlike ships of the line, battleships of the late 19th century and early 20th century were highly vulnerable to torpedoes and sea mines, weapons used by smaller and cheaper ships. The Jeune École school of thought of the 1870s and 1880s recommended deploying torpedo boats alongside battleships in order to hide behind them until the fire of their powerful guns made it difficult for the enemy to see, at which point in which they would make their appearance to launch the torpedoes. Although this tactic became obsolete with the development of smoke propellants, the threat from more capable torpedo boats, and later submarines, remained. By the 1890s the British Royal Navy had developed the first destroyers, initially designed to intercept and repel danger from torpedo attacks. During World War I and afterward battleships were rarely deployed without destroyer cover.

The battleship doctrine emphasized the concentration of battle groups. In order for these concentrated forces to be able to use their force against combat-reluctant opponents, or else to avoid encountering a more powerful enemy fleet, battle fleets needed a means of locating enemy ships beyond the horizon line. And this capability was provided by scouting forces comprised at various times of battlecruisers, cruisers, destroyers, airships, submarines, or aircraft. With the development and entry into use of radio, radar, and traffic analysis, even shore stations became part of battle groups. For most of their history, battleships operated surrounded by squadrons of destroyers and cruisers. The North Sea campaign during World War I illustrates how, despite its cover, the threat of mines and torpedo attacks, and the delay in integrating and making proper use of the capabilities of new technologies, severely limited operations. of the British Grand Fleet, the largest naval fighting force in the world at its time.

Contenido relacionado

Years 260 a. c.

Romance languages

Fax