Battle of the Bagradas Plains

The battle of the Bagradas plains, battle of the Bagradas (the old name of the Meyerda river) or battle of Tunis was a battle fought in the spring of 255 B.C. C., nine years after the start of the first Punic war, between a Carthaginian army under Jantipo and another Roman under Marco Atilio Regulus that ended in victory for the former. In the years before the battle, the newly built Roman Navy established naval superiority over Carthage, an advantage the Romans used to invade the Carthaginian homeland, which today would be located in Tunisia in North Africa. After landing on the Cape Bon peninsula and conducting a successful campaign, the fleet returned to Sicily without Regulus, who was left with 15,500 men to secure quarters in Africa for the winter.

Instead of securing his position, Regulus advanced on the city of Carthage, defeating a Carthaginian army along the way at the Battle of Addis. The Romans went on and captured Tunis, just ten miles from Carthage. Desperate, the Carthaginians sued for peace, but the terms proposed by Regulus were so harsh that they decided to continue fighting. They entrusted the training of their army and, later, the command to the Spartan mercenary commander Jantipo.

In the spring of 255 B.C. In BC, Jantipo led an army strong in cavalry and elephants against the Roman infantry force, who had no effective response against the Carthaginian elephants. The Carthaginians drove the outnumbered Roman cavalry from the battlefield and sent their own, which ended up encircling most of them and annihilating most of the Romans; five hundred survived and were captured, including Regulus. A Roman force of two thousand men avoided being encircled and fell back towards Aspis. The war continued for fourteen more years, mostly in Sicily or in nearby waters, before ending in a Roman victory; the terms offered to Carthage this time were more generous than those proposed by Regulus.

Fonts

The primary source for almost all aspects of the First Punic War is the historian Polybius (200 BC-118 BC), a Greek sent to Rome in 167 BC. as a hostage. His works include a manual — now lost — on military tactics, but The Histories, written after 146 BC, have survived. C., that is, approximately a century after the battle of the Bagradas plains. Polybius's work is widely considered objective and neutral between the Carthaginian and Roman points of view.

Carthaginian written records were destroyed along with their capital, Carthage, in 146 B.C. Thus Polybius's account of the First Punic War is based on various Greek and Latin sources, now lost. Polybius was an analytical historian and whenever possible personally interviewed the participants in the events he wrote about.. Only the first book of the forty that comprises The Histories deals with the First Punic War. The accuracy of Polybius' account has been much debated over the last hundred and fifty years, but there is consensus among modern historians to accept it largely at face value, and details of the battle in modern sources are based almost entirely on interpretations of it. The historian traveled with Scipio Aemilianus to many of the sites associated with the events of 256-255 B.C. while leading an army during the Third Punic War. Historian Andrew Curry considers "Polybius to be quite reliable"; while Dexter Hoyos describes him as "a remarkably well-informed, hard-working and insightful historian". later histories of the war, but in fragmentary or abridged form, and generally describe military operations on land in more detail than at sea. Modern historians also often take into account the later histories of Diodorus Siculus and Cassius Dio, although historian Adrian Goldsworthy states that "Polybius's account is usually preferred when it differs from any of the other accounts".

Other sources of combat include inscriptions, archaeological data, and empirical information from reconstructions such as the Olympias trireme. Since 2010, various artifacts have been recovered from the nearby site of the Battle of the Aegadian Islands, the final fight of the war, which was fought fourteen years later. Their analysis and recovery of other items continue.

Situation

In 264 B.C. the states of Carthage and Rome went to war, the so-called First Punic War. Carthage was a well-established maritime power in the western Mediterranean; Rome had recently unified mainland Italy south of the Arno River. Rome's expansion into southern Italy probably made it inevitable that it would come into conflict with Carthage over Sicily, even if the contest broke out on some pretext. The immediate cause of the war was the dispute over control of the city. Sicilian from Messana (modern Messina).

In 256 B.C. the war had turned into a struggle in which the Romans were trying to defeat the Carthaginians decisively and, at the very least, control all of Sicily. The latter were committed to their traditional policy of waiting for their opponents to wear themselves out, with the expectation of recovering some or all of their possessions and negotiating a mutually satisfactory peace treaty. The Romans were an experienced land attack power, and thanks to this they gained control of much of Sicily. The war reached a stalemate in which the Carthaginians were focused on defending their towns and cities; these were mostly on the coast and could therefore be supplied and reinforced without the Romans being able to use their superior army to interfere.

The focus of the war shifted to the sea, where the Romans had little experience; on the few occasions before the war that they had required a presence at sea, they opted for small squadrons provided by their allies. In 260 BC. The Romans decided to build a fleet, to achieve this they used a wrecked Carthaginian quinquereme as a model for their own ships. Frustration over the continuing stalemate in land warfare in Sicily, combined with victories at Milas (260 BC). C.) and in Sulci, led the Romans to develop a plan to invade the Carthaginian homeland located in the heart of North Africa and thus manage to dawn their capital (now near Tunis). Both sides decided to establish supremacy so they spent large amounts of money and manpower in order to maintain and increase the size of their navies.

Roman tradition established that the command of the armies corresponded to two men elected annually, the consuls. At the beginning of 256 B.C. C., the Roman navy, made up of 330 warships plus an unknown number of transports, set sail from Ostia, the port of Rome, commanded jointly by the two consuls of the year, Marco Atilio Regulo and Lucio Manlio Vulson Longo. approximately twenty-six thousand legionnaires from the Sicilian Roman forces. The Carthaginians were aware of the Roman intentions, and therefore they assembled all the warships available to them, three hundred and fifty, under Hanno and Hamilcar, facing the southern coast of Sicily with the intention of intercepting them. With a total of 680 warships and approximately 290,000 crew members and marines, the battle was probably the largest in history because of the combatants involved. When they met at the Battle of Cape Ecnomus, the Carthaginians they relied on their superior ship maneuvering skills and seized the initiative, as they believed these would be decisive in achieving victory. After a long and confused day of fighting, the Carthaginians were ultimately defeated, with the loss of thirty ships wrecked. and sixty-four captured at Roman losses of twenty-four ships sunk.

Prelude

2: Roman victory in Aspis. (256 BC)

3: The Romans occupy Tunisia. (256 BC)

4: Jantype part of Carthage with a great army. (255 BC)

5: The Romans are defeated in the battle of Tunisia. (255 BC)

6: The Romans retire to Aspis and leave Africa. (255 BC)

As a result of the battle, the Roman army led by Regulus and Longus landed in Africa near Aspis, on the Cape Bon peninsula, and began ravaging the Carthaginian fields in search of food to feed the ninety thousand rowers and crew, and the twenty-six thousand legionaries. They captured twenty thousand slaves, large herds of cattle, and then held a brief siege of the city of Aspis. The Roman Senate sent orders for most of the Roman ships and a large part of the army returned to Sicily under the command of Longus, probably because of the logistical difficulties in supplying more than one hundred thousand men during the winter. In order not to lose their presence in Africa, they left Regulus with forty ships, fifteen thousand infantry and five hundred horsemen. The latter was an experienced military leader who had achieved the position of consul in 267 BC. C., when he was awarded a triumph for his victory over the Messapians, his orders were to weaken the Carthaginian army while he waited for reinforcements to arrive in the spring. It was expected that he would achieve this by raiding and fomenting rebellions among the territories subjugated by Carthage, but the consuls had wide discretion to act as they saw fit. Regulus chose to lead his army inland. He advanced as far as the city of Addis, about forty miles southeast of Carthage, and besieged it. The Carthaginians, meanwhile, recalled Hamilcar from Sicily with five thousand infantry and five hundred cavalry. The latter and two previously unknown chieftains named Hasdrubal and Bostar joined forces to command an army strong in cavalry and elephants and roughly the same size as the Roman one.

The Carthaginians set up camp on a hill near Addis, and in response, the Romans staged a night march, launching a surprise attack on the enemy camp from two directions. The Carthaginians fled after a confused fight. Losses are not recorded, but are known to have been light among the cavalry and elephants. The Romans continued the march, seizing numerous towns along the way, including Tunis, ten miles from Carthage. Tunisia, the Romans looted and felled the surroundings of the Carthaginian capital, and in addition, many of Carthage's African possessions took advantage of this to rebel. The city of Carthage was full of refugees fleeing from Regulus or the rebels, which caused the food to run out, so the desperate Carthaginians decided to ask for peace. Regulus, seeing that Carthage accepted the defeat, he took advantage of it to demand very harsh conditions: he would hand over Sicily, Sardinia and Corsica; he would pay all the war expenses of Rome; he would pay tribute to Rome every year; he would be forbidden to declare war or make peace without Roman permission; he would have his navy limited to a single warship, but he would provide fifty large warships to the Romans at their request. Finding these terms completely unacceptable, the Carthaginians decided to continue fighting.

Armies

Adult male Roman citizens were required to do military service; the majority served as infantry, while the wealthier minority contributed the cavalry contingent. Traditionally, the Romans recruited two legions, each of 4,200 foot and 300 cavalry. A small part of the infantry was made up of skirmishers armed with javelins. The rest were equipped as heavy infantry, with armor, a large shield and short sword. The infantrymen were divided into three ranks: those in the first also carried two javelins, while those in the second and third carried a spear instead. Both legionary subunits and individual legionnaires fought in a relatively open order. Typically, an army was formed by combining a Roman legion with another of similar size and equipment provided by the Latin allies. It is not clear how the 15,500 infantry who fought on the Bagradas River were organized, but possibly they belonged to four legions. with incomplete endowments, two Roman and two allied. Although it is not known why, Regulus did not recruit troops from the towns and cities that rebelled against Carthage, a fact that set him apart from other generals, including the Romans, who commanded armies against Carthage in Africa. In addition, the difficulty in transporting horses had limited his cavalry to just five hundred horsemen, and it is puzzling that he did not try to make up for this deficiency.

Carthaginian citizens only served in the military if there was a direct threat to the city. In most circumstances, the Carthaginian army was drawn from foreigners, many from North Africa, who provided various specialized troops, including: infantry organized in close formation, equipped with large shields, helmets, short swords and long spears, and skirmishers. light infantry armed with javelins; shock cavalry also fighting in close formation—also known as "heavy cavalry"—carrying lances; and light cavalry skirmishers who threw javelins from afar and avoided close combat. Both Spain and Gaul provided veteran infantry: unarmored troops who charged ferociously, though they had a reputation for abandoning combat if it dragged on. Most Carthaginian infantry fought in a compact formation known as a phalanx, usually consisting of two or three lines. Specialized slingers were recruited from the Balearic Islands. The Carthaginians also used war elephants; North Africa was then inhabited by African forest elephants.

Janantipo

The Carthaginians recruited fighters from all over the Mediterranean region, and around this time a large group of recruits from Greece arrived in Carthage. Among them was Janippus, a Spartan mercenary commander. Polybius claims that he participated in training methods peculiar to his homeland and that he knew both how to deploy and maneuver an army. He made a good impression among the troops of the Carthaginian army and was able to persuade the Carthaginian Senate that the strongest elements in his army were cavalry and elephants and that to achieve the most efficient result they should fight on level ground. Historian John Lazenby speculates that he may have previously faced elephants when Pyrrhus of Epirus attacked Sparta in the 270s BC. Jantipo was placed in charge of training during the winter, although a committee of Carthaginian generals retained operational control. As the prospect of a decisive battle loomed and Jantipo's ability to maneuver the army became more apparent, he was granted full control. It is not clear if it was a decision of the Senate, of the generals, or was imposed by the wishes of the troops, who included many Carthaginian citizens.

Battle

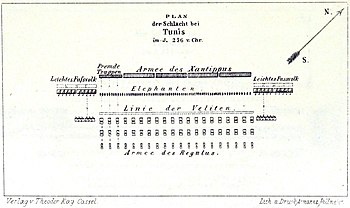

Janippus led the army, consisting of one hundred elephants, four thousand cavalry, and twelve thousand infantry—including five thousand Sicilian veterans and many citizen militias—from Carthage and established a camp on a plain near where the soldiers stood. romans. The exact location is unknown, but it is assumed that they settled near Tunis. The Roman forces, consisting of fifteen thousand infantry and five hundred cavalry, advanced to meet them, and camped about two kilometers away from their enemies. Both sides fanned out for battle the next morning. Xantipo placed the Carthaginian militia in the center of the formation, with the Sicilian veterans and newly recruited infantry on the flanks; the cavalry was divided evenly in two and arranged to cover the flanks of the infantry and the elephants were deployed in a single front line in the center of the infantry. deep and dense than usual. Polybius considers it an effective formation against elephants, but notes that it shortened the front of the infantry and made it more prone to being outflanked. Light infantry skirmishers moved ahead of the legions, and five hundred horsemen were divided between the flanks. Regulus seems to have hoped to breach the elephant formation by massing the infantry, then defeat the Carthaginian phalanx center and thus achieve victory before having to worry about being attacked from the flanks.

The battle began with charges from Carthaginian cavalry and elephants. The outnumbered Roman horsemen soon ended up being swept off the battlefield. The Roman legions advanced, shouting and banging their sword hilts on their shields in an effort to scare off the elephants. Part of the Roman left flank, probably made up of Latin allies, blended into the line of elephants and charged the infantry. Carthaginian on the right side, who could not stand the onslaught and fled towards their camp. The rest of the Roman infantry had difficulty facing the elephants, indifferent to the noise with which they were trying to scare them and charged towards the enemy, which caused casualties and great confusion. At least some of the legionaries forced their way through the elephant line and attacked the Carthaginian phalanx, but they were too disordered to fight effectively and the enemy held their ground. At this point, some Carthaginian horsemen returned from their pursuit of the enemy cavalry and began to harass or feint against the Roman rear and flanks. The latter tried to fight from all sides, which halted their advance.

The Romans held their ground, possibly in part because of the dense formation in which they had been deployed, but the elephants continued to rampage through their ranks, and the Carthaginian cavalry managed to pin them down by firing shells to their rear and flanks. Then, Jantipo gave the order to attack the phalanx that ended up cornering most of the Romans in a space where they could not effectively resist the enemy attacks and where they ended up perishing. Regulus and a small force fought their way out of the encirclement, but were pursued and shortly afterwards he and five hundred survivors were forced to surrender. As a result, a total of thirteen thousand Roman soldiers were killed. The Carthaginians, for their part, lost eight hundred men on the right flank, the one that had routed the Roman infantry; the losses of the rest of the army are unknown. Two thousand Romans survived, from the left wing that had broken into the enemy camp; they escaped from the battlefield and withdrew towards Aspis. This was Carthage's only major victory in a land battle during the war.

Consequences

Janippus, fearful of the envy of the Carthaginian generals he had outmaneuvered, accepted his pay and returned to Greece. Regulus died in Carthaginian captivity; Later Roman authors invented a story showing heroic virtues while he was a prisoner.The Romans sent a fleet to evacuate the survivors from him and the Carthaginians tried to stop them. In the resulting battle, at Cape Hermeo, off Africa, the Carthaginians suffered a resounding defeat; the enemy seized 114 of their ships with their crews and sank another 16. The Roman fleet, in turn, was devastated by a storm while returning to Italy, losing 384 of its 464 warships and more. of 100,000 men, most of them Latin allies of the Romans. The war continued for fourteen more years, mainly in Sicily or nearby waters, before ending in a Roman victory; the terms offered to Carthage this time were more generous than those proposed by Regulus. The question of which state would control the western Mediterranean remained unresolved, and the two maintained a tense relationship. When Carthage besieged Saguntum —present-day Sagunto, in eastern Iberia— in 218 B.C. C., a city protected by the Romans, precipitated the second Punic war with Rome.