Battle of Qadesh

The battle of Qadesh took place between the forces of the Egyptian New Kingdom, ruled by Ramesses II, and the Hittite Empire, ruled by Muwatalli II, in the city of Qadesh, on the Orontes River, in the vicinity of Lake Homs, near the Syrian border with Lebanon.

The battle is generally dated to around 1274 BC. C. by Egyptian chronology. It is the first battle for which detailed historical records of formations and tactics are preserved. It is believed to have been the largest chariot battle ever fought, with between 5,000 and 6,000 chariots having participated.

As a result of the multiple Qadesh inscriptions, it is the best-documented battle of antiquity.

The Hittites attacked first and were about to defeat the Egyptians, although thanks to the command of Ramses II the Egyptians managed to counteract the attack and the battle ended in a draw. After this, Ramses II and Hattusili III signed the first history peace treaty.

It was the last great military event of the Bronze Age.

Ancient sources

Egyptian

Shortly after the battle, Ramses II ordered its commemoration on the walls of several of his temples, attesting to the importance of the event to his reign. The battle of Qadesh is described in five temples: some fragments on two walls of the Abydos temple, probably the oldest; in three places in the temple of Amun in Luxor; two in each of the large courtyards of the Ramesseum, which was the funerary temple of Ramses II in Tebas-Oeste; and finally a shorter representation in the first hypostyle hall of the main temple of Abu Simbel in Nubia. There are also two copies of these texts on papyri written in hieratic.

Three texts sponsored by Ramses II and of which many copies exist explain the battle.

- The Pentaur Poem It is a story of the battle that Ramses II entrusted to the Pentaour scribe. It is an extensive text, of which there are eight copies in different temples and others in papyrus. It is the most detailed and poetic description of combat and the most outstanding qualities of Pharaoh are described, highlighting his relationship with the god Amon.

- The War bulletin It's a shorter text. There are seven copies in bas-relieve next to the copies Poem.

- The accounts of the bas-reliefs constitute a third written source. These comments from the figurative representations of the battle sometimes provide information that is not found in the other two texts.

Hittites

No Hittite text is known to describe the battle of Qadesh. Muwatalli II did not leave any official text commemorating his military campaigns, but the conflict with Ramses II is mentioned in texts from his successors: the Apology of Hattusili III (CTH 81) and a decree of Hattusili III (CTH 86), which was Muwatalli II's brother and who was present on the battlefield, as well as the story in the prologue to the treaty signed by his son, Tudhaliya IV, and the king of Amurru, Shaushgamuwa (CTH 105). Qadesh seems to be evoked in letters sent by Ramses II to Hattusili III, although there is little information about it.

The Treaty of Qadesh

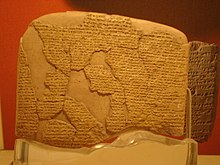

The document that formalized the truce between Egypt and the Hittite Empire, known as the Treaty of Qadesh, is the first text in history that documents a peace treaty. It was copied in numerous copies written in Chaldean Babylonian (the lingua franca of diplomacy of the time) on precious silver leaves. Several copies have been found in Hattusa, the Hittite capital, while other copies were found in Egypt.

Other copies written on baser materials, containing the same text, have also come down to us, such as the set of clay tablets preserved in the Istanbul Archeology Museum, corresponding to the Hittite version of the treatise.

Historical context

The importance of Syria

A meeting, crossing and negotiation point for the traffic and commerce of its time, and an area endowed with immeasurable natural resources, Syria was the commercial, cultural and military crossroads of the ancient world. Not only did it produce huge amounts of wheat, but the merchandise from the ships that crossed the Aegean and those from more distant places passed through it, arriving in Asia Minor through the port of Ugarit, a kind of ancient Venice that dominated the commerce of the Eastern Mediterranean, and was, precisely, located in Syria. The customs duties that would be collected by whoever controlled the region were enormous; added to its strategic military position, agricultural production and traffic and export rights, made the area one of the most strategically important in the ancient world.

Glass, copper, tin, precious woods, jewelry, textiles, food, luxury items, chemicals, china and porcelain, tools and precious metals traveled through the area. Through a web of trade routes that began and ended in Syria, these goods were distributed throughout the Middle East, while other products arrived there from as far away as Iran and Afghanistan.

Between two powers

But Syria suffered the disadvantage of being in the middle of the two great political and military powers of its time: the Egyptian empire and Hatti, the immense Hittite empire. Obviously, both wanted to dominate Syria in order to exploit it for their own benefit. In fact, today it is considered that, 3300 years ago, the mere fact of controlling the Syrian land meant the automatic promotion of any nation to the exclusive elite of those who deserved to be called "world power". This is how Mittani seemed to understand it first, Hatti and Egypt later, and Assyria and Nebuchadnezzar last.

It is understandable, therefore, that Mittani, Hatti and Egypt spilled, during the centuries before Qadesh, true oceans of blood in their desperate attempts to dominate the region, thus providing a violent general scenario where the specific factors that would move would move. They would go into battle.

Background

After the campaigns of the Hittite monarch Suppiluliuma I against the kingdom of Mittani, in the north of present-day Syria, between the years 1340 and 1330 BC. C., Mittani disintegrated and the Hittites came to dominate most of Syria. Several vassal places of the Egyptians fell in the Hittite campaign, such as the kingdom of Amurru and Qadesh, but it does not seem that Pharaoh Akhenaten considered the option of fighting to recover them. There was a conflict between Egypt and the Hittite Empire when, according to Hittite sources, the Egyptian queen Anjesenamón, widow of Tutankhamun, asked Suppiluliuma I for one of her sons in marriage to make him king of Egypt. The Hittite king accepted the proposal and sent his son Zannanza as betrothed to the queen, but he was assassinated on the way. The Hittite king chose to confront Egypt despite the friendship treaty the two countries had signed long ago.

At the beginning of the XIII century B.C. C., the Egyptians and the Hittites had more than twenty years of conflictive relationship.

The conflicts, led by the sons of the old Hittite king, did not yield significant results. The Egyptian response to Hittite progress came only with Horemheb, considered the last pharaoh of the Eighteenth Dynasty. He supported a revolt by several Hittite vassals, including Qadesh and Nuhasse, who were difficult to subdue by the Hittite troops led by those princes, including those of Karkemish. King Mursili II later intervened in person to restore cohesion among his vassals, signing several peace treaties with them.

But the tide turned, and the Hittites went on the defensive against the Egyptians. Seti I, the second pharaoh of the 19th dynasty, led an Egyptian counterattack to recapture his lost vassals. He commemorated his victory against the Hittites with an inscription and a relief on a temple at Karnak. He seized Qadesh and the Benteshina king of Amurru joined his campaign.The Hittite troops were led by the Viceroy of Karkemish, who oversaw Hittite rule in Syria. King Muwatalli II was in western Anatolia dealing with a rebellion more serious than the situation in Syria, despite the fact that the region's other adversaries, the Assyrians, were also advancing. The Hittite reaction is slow. Qadesh returned to Hittite control in the following years for unknown reasons, as Hittite sources do not mention this fact.

Dating to the end of Egypt's 18th Dynasty, the Amarna Letters tell the story of the decline of Egyptian influence in the region. The Egyptians showed little interest in the region in the late 18th Dynasty.

This continued into the 19th Dynasty. Like his father, Ramses I, Seti I was a military chief who set out to make the Egyptian Empire like it was in the times of Kings Tutmosis I, Tutmosis II, and Tutmosis III, a century earlier. Inscriptions on the walls of Karnak record details of Seti I's campaigns in Canaan and ancient Syria, he reoccupied abandoned Egyptian positions and fortified cities. However, those regions later returned to Hittite control.

With the arrival of Ramses II, around 1279 B.C. C., only Amurru remained as an ally in the Egyptian campaign, but Muwatalli tried to get them to join him. The first three years of the new pharaoh's reign were devoted to internal affairs. In the fourth year of his reign, 1275 B.C. C., he carried out a first campaign to Amurru, probably passing by sea. He left a stele at Nahr el-Kelb, on the central coast of Lebanon.This expedition was made to show support for his vassal against the Hittites.

In May 1274 B.C. C., the fifth year of his reign, Ramesses II began a campaign from his capital, Pi-Ramesses (modern Qantir). The army moved to the Tjel fortress and went up the coast to Gaza.

The status quo: Hatti and Mittani

Two generations before Ramses, the picture had been different: the dominant powers in the region were not Egypt and Hatti but Egypt and the great kingdom of Mittani. Thutmosis IV (1425-1417 BC) had managed to formalize a lasting peace, aware that, with two large kingdoms and many small ones in the area, the two powerful ones could only dominate the others if they did not make war against each other.

Knowing this fact, the powerful Hittite king Suppiluliuma I understood that, in order to become one of the two great ones, he had to destroy the weaker of them and replace him. He thus initiated a long-term project of complete and systematic destruction of Mittani, paying particular attention to the project of eradicating him from his military, commercial and industrial positions in northern Syria.

The pharaohs Thutmosis III and his son Amenhotep II did not react to this fact, because Mittani had been taking Syrian territories from them for two centuries, and they may have believed that everything that was bad for their enemy would be good for them.

Thus, the king of Mittani, Shaushtatar, decided to approach Egypt to see if the aggressiveness of the Hittites would stop. He did not want to be forced to fight a war on two fronts, against the Egyptians to the south and the Hittites to the east. He offered the Egyptians a treaty of "brotherhood"; that it was accepted, and the emissaries from him arrived in Egypt in the tenth year of the reign of Amenhotep (1418 BC?) with tributes and greetings to the pharaoh.

Egypt-Mittani Alliance

The successors of Amenhotep II and Shaushatar—Amenhotep III and Artatama I—finally formalized the pact, adding a blood union to the political friendship between Mittani and Egypt: the Egyptian emperor married the daughter of the Mittani king, Taduhepa.

Once all the objectives of unity, non-aggression and free trade had been achieved, it was time to meticulously define the borders between both empires, which consisted, precisely, of Central Syria, in territories coveted by both and also by the Hittites.

By means of a boundary treaty —which has never been found—, Artatama recognized Egyptian rights over the kingdom of Amurru, the valley of the Eleutheros river and the cities of Qadesh (the new one, on a strategic promontory, and the old woman next to him, on the plain).

To compensate for these cessions, Amenhotep renounced forever the then Mittanian territories but which had been Egyptian by virtue of the conquests of the great warrior pharaohs of the Eighteenth Dynasty: Thutmosis I and Thutmosis III.

The treaty was so satisfactory for both parties that more than two centuries of peace and prosperity, mutual respect and friendship followed from its formalization. The stability of those borders lasted so long that they were imprinted in the minds of all those who inhabited the region as static limits and impossible to change.

Peace

Amenhotep III's successful diplomacy removed the Hittites from the equation: Hatti had returned to being a "little kingdom" among the great powers. The peace dividends were so great, and Mittani and Egypt became so powerful, that no one in Hatti could dream of unseating either. Adding this to the threat of a third power that was rising behind them, in the east - Kassite Assyria -, the Hittites were forced to accept their role as extras in the great work of growth carried out by the three powers that dominated the world. during the next two centuries: Assyrians, Egyptians, and Mitanians.

The strategic region of Amurru and Qadesh

Amurru was the name with which the Egyptians colloquially called the strategic valley of Eleutheros (Gr.; "River of Free Men"), a kind of land corridor that allowed them to reach from the coast and its ports the advanced positions in Central Syria, located on the banks of the Orontes River. Amurru was thus vital to the pharaohs.

But Amurru wasn't just important for trade and peace: previous kings had had to keep the pass open so they could send their armies north to make war on Mittani. And it happened that, to keep the Amurru pass at its disposal, Egypt had to dominate the city of Qadesh, on the Orontes. Qadesh fall, Amurru would fall and Egyptian trade and communications would be completely annulled. This fact alone is the justification for Ramses' entire Syrian war, and for the efforts of his predecessors to keep the area in his hands.

The Satellite States

The very precise demarcation of the limits between Mittani and Egypt, consequence of the treaty of two centuries before, and the subsequent peace, made possible the establishment of numerous kingdoms or "intermediate" states, vassals of one or the other of the powerful empires, which behaved like modern "satellite countries" that populated Europe and Asia in the 20th century.

These satellites softened the possible tensions between the two, becoming "lubricants" or intermediaries who, out of their own interest, did what was in their power to maintain peace and harmony. Being border states, weak militarily but rich and located in strategic positions, their rulers were clear that they would be the first to disappear if a conflict broke out. With no territorial ambitions other than for their own survival, the satellite states had much to lose and nothing to gain in the event of a military confrontation in the region.

The Amorite Kingdoms

However, the reign of Amenhotep III saw the birth of a new emerging power: a strange political unit that called itself the "kingdom of the Amurru" (or Amorites) and who immediately began to cause trouble.

This kingdom did not exist at the time of the delimitation of the borders, but fell on the Egyptian side, so the Hittites did not recognize its sovereignty or legal entity as an independent country. A leader named Abdi-Ashirta, and later his son Aziru, began to organize the heterogeneous constellation of tribes that populated the place, and, with some skill, managed to unite them in a political structure that dominated, at the end of the century XIV a. C., all the critical territory, that is, the one located between the Mediterranean beach and the Orontes river.

Not satisfied with this, Abdi-Ashirta and Aziru managed to expand the borders of their small kingdom, exploiting the indifference that the Egyptian court manifested towards the region. The neighboring states, which saw their borders dwindle at the expense of Amorite expansionist ambitions, turned to Pharaoh to request that, by sending troops, he impose discipline on his vassal, to which the emperor refused.

Ultimately, it was Mittani that was affected by territorial spoils, and this kingdom was not in the habit of remaining undaunted by invasions. Mittani sent an expedition to destroy Amorite power—Abdi-Ashirta is believed to have been killed in this conflict—and achieved his goal, but the damage was done. As expected, the Mittan troops did not withdraw after the destruction of Amurru, and the pharaoh, who could not tolerate that one of his powerful neighbors had troops stationed in his territory, was forced to undertake, he too, military actions.

Amenhotep sent the army to dislodge the Mittans, and this move spelled the end of two centuries of peace and the liquefaction of borders so painstakingly drawn and held. It was also the beginning of the controversy that would culminate on the battlefield of Qadeš.

Suppiluliuma I the Great

Suppiluliuma I the Great was crowned King of Hatti around 1380 BCE. C., and from the day of his ascension he demonstrated that his main interest was to obtain and maintain Hittite control of North and Central Syria. He immediately attacked Mittani and seized the kingdoms of Aleppo, Nuhashshe, Tunip and Alalakh from him. This conflict is known as the first Syrian war.

Ten years later, Mittani tried to take them back by force. Suppiluliuma saw this initiative as enabling him to strike again, and so the second Syrian war brought destruction and chaos to the neighboring kingdom. Waššukanni, the capital and main city of the Mitanni kingdom, was sacked and burned. The Hittites crossed the Euphrates and, turning west, captured Syria, which is now believed to have always been their true objective.

Hatti made treaties with the captured ex-Mitanian kingdoms, declared them his vassals, and occupied the south, reaching Carchemish and taking over—in addition to those named—the vassal states of Mukish, Niya, Arakhtu, and Qatna.

Akhenaten

Meanwhile, in his palace at Akhetaten, the young pharaoh Amenhotep IV, who would go down to posterity as Akhenaten, watched the unstoppable Hittite advance with apparent disinterest. Many historians attribute to him the fact of having tolerated the fall of the important commercial city of Ugarit and the strategic stronghold of Qadesh without having intervened to prevent it or to recover them later.

Modern theory explains, in part, Akhenaten's attitude: seen from Amarna, Qadesh and Ugarit were outside the new borders established for Egyptian territory, making their conquest or loss an a matter exclusive to the Mittano-Hittite conflict, in which Egypt would not intervene as long as it could avoid it. The pharaoh already had enough problems with his resisted reform of the belief system and Egypt's conversion to a monotheistic religion to worry about what to him were small villages more than 500 miles away. Furthermore, Suppiluliuma had made it clear to him that Hatti would not cross borders, and that peace between Egyptians and Hittites would be assured as long as he lived.

In fact, the Hittite conquest of Qadesh had been the unintended consequence of an imponderable: it had never been in Suppiluliuma's mind to attack a vassal state of Akhenaten. What happened was this: the king of Qadesh, acting on his own account and without consulting Amarna, had blocked the passage of the Hittite troops through the Orontes valley, forcing Suppiluliuma to attack him and capture the city from him. The king and his son Aitakama were taken as prisoners to the Hittite capital of Hattusa but Suppiluliuma cleverly returned them safely so as not to make an excuse for Akhenaten to start the fearsome Nilotic war machine.

Qadesh against Egypt

Suppiluliuma restored, after the war, the status of Egyptian vassal to the kingdom of Qadesh and, for a time, everything seemed to return to normal.

But upon the death of his father and once crowned king, the young Aitakama began to behave as if he were actually a Hittite agent. Some neighboring vassal kings notified Akhenaten about his conduct, which basically consisted of anticipating that he would attack the city of Upe (another important Egyptian vassal and, therefore, his equal to him), & # 34; suggesting & # 34; # 3. 4; to support him in that campaign.

Once again, Egypt decided not to intervene. Instead of sending in the army and imposing order by force, Akhenaten contacted Aziru, King of Amurru, and ordered him to protect Egyptian interests in the region, defending them from Aitakama's voracity.

True to his father's style, Aziru accepted the pharaoh's gold and supplies, but instead of using them as he had been commanded, he invested them in beginning his own expansionist process at the expense of his neighbors.

Akhenaten fails

Knowing that Aziru of Amurru had a diplomatic mission from Hatti at his court, Akhenaten understood that the time for words had finally passed: with Qadesh on the Hittite side and Amurru negotiating with the strategic enemy of Egypt, he was the time to adopt a military solution.

Although there are no documents to prove it, today it is believed that Pharaoh sent an army that was defeated. Thereafter the recovery of Amurru, Qadesh and the Orontes valley became a priority objective for the remaining pharaohs of the Eighteenth and early XIXth Dynasties.

In this way, the strategic area remained under Hittite rule until Ramses decided to recover it.

Seti II

After the deaths of Akhenaten and his son Tutankhamun, Egypt was involved in a succession of three military dictatorships led by army chiefs. This situation, which lasted for thirty-two years, was the consequence of the institutional chaos inherited after Akhenaten's attempt at social and religious reform. Any ambition of these three generals to recover Syria had to be postponed because of the most terrible and urgent need to appease the internal sphere of the nation, threatened by civil war.

However, the last of the three, Horemheb, left well established what would be the Egyptian position in relation to Amurru from then on: the policy of indirect rule through the petty vassal kings of the region would be abandoned, and the would implement a full-blown military occupation.

When the 19th Dynasty began after him, his successor, Ramses I and later his son, Seti I, wanted to recover the disputed areas. Seti I immediately undertook (in the year 2 of his reign) a campaign that was an imitation of those of Thutmosis III. He took command of an army that headed north, with the goal of "destroying the lands of Qadesh and Amurru," as his military monument at Karnak bluntly explains.

Seti managed to recapture Qadesh, but Amurru remained on the Hittite side. Pharaoh continued north and faced a Hittite levy army, which was easily destroyed. Hatti did not oppose him with more conspicuous forces because at that time his professional army was engaged against the Assyrians on the eastern frontier.

The solution was temporary, however: to the date of Seti I's death (XIV century BCE)..|1279 BC]]), Qadesh was again in Hittite hands, and the situation would remain in an unstable equilibrium for four more years. By then, there were already two new kings sitting on the thrones of the opposing kingdoms.

Last Try

In 1301 B.C. C., Ramses II, son of Seti I, made a drastic decision: to maintain Syria he needed Qadesh, and it would not submit to a mere messenger. He therefore headed north with a large army, to personally receive the oath of allegiance from the Amorite king, Benteshina, "motivated," perhaps, by the grim sight of thousands of escorting soldiers. to pharaoh. It is quite clear that Ramses II's intention was to subdue Qadesh, willingly or by force.

Hatti had a new king, the clever and cunning Muwatalli II. Muwatalli was not unaware of the intentions of the young Ramses, and he was also not forgetting that it was imperative for Egypt to dominate Qadesh if he ever wanted to regain control over Syria. Under such circumstances, he understood that he was obliged to act. If Benteshina were kidnapped or taken over by Egypt and if Amurru fell to the Emperor of the Nile, the Hittites stood to lose all of central and northern Syria, including strategic strategic hotspots like Aleppo and Carchemish.

However, the Hittites could now concentrate on a single front, because recent treaties had eliminated the Assyrian threat behind their backs. So in the summer of 1301 B.C. C., Muwatalli began to organize a large army that, he hoped, would put an end to the Egyptian campaign. The battlefield was very clear to both commanders: they would fight under the walls of Qadesh. Egypt and Hatti would meet once and for all in a final combat, a huge battle that would ultimately define whether Syria would fall under Pharaonic or Hittite rule.

Commanders of both armies

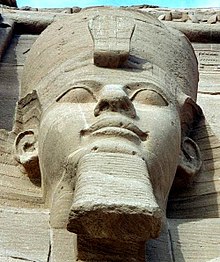

Ramesses II

Crown prince of the 19th Dynasty, grandson of its founder Ramesses I and son of Seti I, Ramesses was educated like all future pharaohs of his day. He was taught to ride chariots as well as walk, to tame and ride horses and camels, to fight with a spear, and—most important of all—to shoot a bow with impressive accuracy from the platform of a chariot launched at the race.

Princes with a chance of reaching the throne were taken from their mothers at a very young age—perhaps four or five years old—and sent to spend the rest of their childhood and adolescence in military camps, left in the care of one or several generals who would raise them and educate them in the arts of war, as befitted those who, probably, should perform in the future as powerful warrior kings.

Between the ages of sixteen and twenty, Ramesses accompanied his father on campaigns in Libya and Syria. Upon Seti's unexpected death, the double crown was placed on his head when Ramesses was between twenty-four and twenty-six years old. He was already a skilled warrior, and fully convinced of the vital importance of Qadesh and Amurru to the future of his empire.

He prepared from a young age for this conflict, disregarding the terms of the treaty his father had signed with the Hittites in the national interest. Three years before the beginning of the campaign, Ramses made great and profound changes in the organization of the army and rebuilt the ancient Hyksan capital of Avaris (renaming it Pi-Ramesses) to use it as a large military base in the future Asiatic campaign.

Muwatalli

We know very little about the Hittite ruler: he was crowned four years before Ramesses, and was the second of four sons of King Mursili II, Seti I's opponent in the previous Syrian war.

On the death of Mursili II, his eldest son inherited the throne, but his premature death placed Muwatalli in the position of predominance he needed to try to keep the disputed area. He was a competent and strong ruler, quite honest and a very good administrator: he reorganized the entire administration of his empire in order to assemble the huge army that would face the Egyptians at Qadesh. Never, neither before nor after, any other Hittite monarch would manage to gather a force similar in number and power.

The opposing armies

Hittite Army

What is now known as the Hittite army was, in reality, the armed force of a huge confederation recruited from all corners of the great empire. It was composed of troops from Hatti and from seventeen other neighboring or vassal states. The following table shows them with their commanders (when their names are known) and the troops contributed by each of them.

Kingdom Commander Sport to the army Hatti Muwatalli I 500 cars and 5000 infants Hakpis Hattushillish 500 cars and 5000 infants Pitassa Mittanamuwash 500 cars and 5000 infants Wilusa, Mira and Hapalla Piyama-Inarash? 500 cars and 5000 infants Masa, Karkisa and Arawanna Unknown 200 cars and 4000 infants Kizzuwadna Unknown 200 cars and 2000 infants Carchemish Sahurunuwash 200 cars and 2000 infants Mitanni Sattuara 200 cars and 2000 infants Ugarit Niqmepa 200 cars and 2000 infants Aleppo Talmi-Sarruma 200 cars and 2000 infants Qadesh Niqmaddu 200 cars and 2000 infants Lukka Unknown 100 cars and 2000 infants Seha River Country Masturish 100 cars and 1000 infants Nuhashshe Unknown 100 cars and 1000 infants Total 3700 cars and 40 000 infants

Organization

Like most Bronze Age armies, the Hittite army was organized around its efficient tank force and powerful infantry.

The chariots were a small and hardened nucleus in times of peace, which was quickly increased when a war loomed, recruiting numerous men from the reserves. These rich fighting peasants fulfilled their feudal obligations to the king by enlisting. Unlike many feudal levies of the day, Hittite tankers underwent regular training sessions, making them fearsome and feared units.

The arm of chariots, predecessor of the later cavalries, was made up of soldiers from the small rural aristocracy and the low nobility, of high economic power —which was, obviously, essential to be able to attend to the maintenance of the chariots, their horses and crews. The expenses that the cars caused were also part of the feudal obligation towards the crown. Still, to achieve the large numbers of chariots that Muwatalli considered necessary for success at Qadesh, he undoubtedly had to call on many mercenary charioteers.

The expense that the organization of its chariot units meant for the Hittite state forced the leaders to order their troops to donate their soldiers to the crown. This was only accepted in exchange for the full loot being awarded to them. The appetite of the Hittite soldiers for the looting of the Egyptian camp explains the events that occurred in the first phase of the battle.

The three crew members of the Hittite chariot —whom Ramses pejoratively called "effeminate" or "women-soldiers" Due to his habit of wearing long hair, they were the driver —unarmed, since he needed both hands to drive the cart—, the lancer and a squire, in charge of protecting the other two.

However, these chariots of three (which P'Ra had to face in the approach march) constituted only the Hittite national force. Their other Syrian allies went to combat in two-man chariots called mariyannu, copied from the Hurrian warfare tradition, lighter and with similar uses to those of their Egyptian equivalents.

The infantry was, for the Hittite commanders, a subsidiary and secondary weapon with respect to the chariots. Their uniforms were highly varied, reflecting the various physical and weather conditions in which they fought. In Qadesh they used a long white smock, unusual in other campaigns.

The infant used to carry a sickle-shaped bronze sword and a bronze battle-axe, although iron weapons were already beginning to make their appearance in Qadesh times. Likewise, Muwatalli's personal guard (called thr) carried long spears like those of the charioteers and the same daggers as them.

Although it is known that Hittite soldiers used to wear helmets and mail of bronze sheets, there are very few Egyptian reliefs that show them with them. Regarding the plate armor, it has been suggested that they were used in Qadesh, but that they were hidden by the overalls.

Tactical Use

Unlike the Egyptian army, the Hittites used chariots as their primary offensive weapon. This attitude is evident from the very design of the car itself. It was considered a basic assault weapon, created to break through the ranks of enemy infantry and open gaps in it that the infantry itself could penetrate. That is why, although the crews were equipped with powerful recurve bows, the weapon they used at all times was the long throwing spear.

The Hittite chariot, unlike the Egyptian, had the axis located in the center of the chassis and was heavier, since it had a crew of three. These two characteristics made it slower and less maneuverable than its opponent, also having a clear tendency to capsize if it was intended to turn at tight angles. Therefore, it needed vast empty spaces to maneuver. Its advantage consisted in its greater mass and inertia, which made it fearsome when launching at speed. When momentum and inertia dissipated (for example, when traversing hills or obstacles), the Hittite chariot's advantage was diluted.

The infantry, as has been said, had to penetrate the gaps opened by the tanks in the enemy infantry, and for this reason it was considered only a secondary force. Whenever possible, the Hittite generals tried to surprise their enemy in open fields of such dimensions as to allow them to take advantage of their heavy tanks, while having enough space to turn with their large turning angles.

Egyptian Army

The army of Ramesses II, with its countless chariots, infantry, archers, standard bearers, and music bands, was the largest assembled by an Egyptian pharaoh for an offensive operation, up to that time.

Although the Egyptian military presence in Syria had been almost constant during the Old and Middle Kingdoms, the structure of the one that went to Qadesh is typical of the New Kingdom and was designed in the middle of the century XVI a. c.

The organization of the army imitated that of the state, and was a direct consequence of the Egyptian victory over the Hyksos, which suddenly put the pharaohs in charge of a territory that reached as far as the Euphrates. To control such a tract of land required the creation of a permanent professional army, equipped with all the weapons that late Bronze Age technology could procure. Egypt had thus become a military state. The fact that the princes were raised by generals and not by wet nurses is the most lapidary proof of this point.

The close union between the army and the state allowed, for example, that after the death of Tutankhamen and his successor Ay, a series of military dictators were established in the government, three generals who proclaimed themselves pharaohs and marked the end of the XVIII century Dynasty. When the last of these - Horemheb - died, power passed to Ramses I, Seti I and Ramses II, legitimate rulers, but the concept that a general could establish himself as pharaoh had already penetrated the minds of all the subjects, and mainly of the military. Military coup aside, it was clearly possible for a soldier to grow economically and socially through his participation in the army, and he could very well rise through the nobility and even reach court. Normally, in addition, the officers who went into effective retirement were appointed personal assistants of the nobles, state administrators or tutors of the king's children.

The army was seen, then, as an important tool of social progress. Particularly for the poor, it presented opportunities never before seen by the farmer who stayed on his land. Since there was no distinction between troops, non-commissioned officers, and officers—a private could rise to army general if his capacity permitted—and they were given a significant share of the rich booty obtained, the ambition of many workers was to move into the ranks. of the royal militia as soon as possible.

The papyri of the time prove that all veterans were deeded to large tracts of land that were legally in their hands forever. The soldier also received herds and personnel from the royal household's service corps so that he could immediately work the newly obtained land. The only condition required of him was that he reserve one of his sons to join the army. A papyrus relating to taxes, dated around 1315 BC. C. (under Seti I), lists these advantages granted to a lieutenant general, a captain, and numerous battalion chiefs, marines, standard bearers, tankers, and army administrative scribes.

Each soldier was to "fight for his good name" and defend Pharaoh like a son to his father, giving him a title or decoration called "The Gold of Courage" if he fought well. If he showed cowardice or fled from combat, he was denigrated, degraded and, in certain cases, like Qadesh, he could even be executed summarily and without trial, at the sole discretion of the king.

Organization

The Egyptian army was traditionally organized into large army corps (or divisions, depending on the terminology used) organized at the local level, each numbering about 5,000 men (4,000 infantry and 1,000 charioteers manning the 500 added war chariots to each body or division).

Although it is believed that there were four such corps in the time of Thutmosis III (in the battle of Megiddo, as a passage on a single papyrus seems to indicate), a decree of Horemheb ratified the ancestral structure of two army corps. Aware of the need to amass a large force to combat the Hittites, Ramesses II enlarged and reorganized the two-corps army that Seti had brought to Syria, restoring the four-corps scheme (or creating it, as stated). It is possible that the Third Corps existed as early as Ramesses I or Seti I, but there is no doubt that the Fourth was founded by Ramesses II. This structure, added to the high mobility of the units, gave Ramses great tactical flexibility.

Each army corps received as emblem the effigy of the tutelary god of the city where it had been created, normally resided and served as its base, and each one also had its own supply units, combat support services, logistics and intelligence.

The structure of the army in the time of Qadesh was as follows:

| Army Corps | Name | Emblema - God Tutelar | Based on | Founded by |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First Corps | "Poder of the Arcos" | Amon | There. | Traditional |

| Second Corps | "Abundance of Value" | P'Ra | Heliópolis | Traditional |

| Third Body | "Force of the Arcos" | Sutekh (Seth) | Pi-Ramsés | Ramses I or Seti I |

| Fourth Body | Unknown | Ptah | Menfis | Ramses II |

The 4,000 infantry of each army corps were organized into 20 companies or sa of between 200 and 250 men each. These companies bore sonorous and picturesque names, many of which have come down to us, such as "Prowling Lion", "Nubian Bull", "Destroyers of Syria", "Radiances of Aten" or "Justice Manifested".

The companies, in turn, were divided into units of 50 men. In combat, companies and units adopted a phalanx structure: veteran (menfyt) soldiers were in the vanguard, and freshmen, conscripts and reservists (called nefru) in the rear.

The many foreign units that fought alongside Ramses (mercenaries and also prisoners of war who were offered life, liberty, part of the booty and land if they fought for Egypt) maintained their identity by organizing themselves into separate units by nationality and attached to one or another army corps, or as auxiliary, support or service units. Such was the case of the Canaanites, Nubians, sherden (Pharaoh's bodyguard, possibly primitive inhabitants of the island of Sardinia), etc.

The nakhtu-aa, known as "Those with strong arms" they were special units trained for hand-to-hand combat. They were very well armed, but their shields and armor were rudimentary.

The primary weapon of the Egyptian army, used in large numbers by both infantry and chariot crews, was the fearsome Egyptian mixed bow. These bows fired long arrows capable of piercing any armor of the time, which is why, in the hands of a good marksman, they became the most lethal weapon on the battlefield.

In addition to the bow, Egyptian soldiers carried khopesh, scythe-like bronze swords in the shape of a horse's leg, short daggers, and bronze-headed battle-axes.

The tank units were not organized as their own corps, but in the manner of current regimental artillery: they were added to the army corps, on which they depended, in a proportion of 25 tanks for each company. Two lighter and faster variants were added to the combat versions: one type dedicated to communications and another for exploration and advanced observation.

Ten chariots made up a squad, fifty (five squads) a squad, and five squads a larger unit called a pedjet (battalion), made up of 250 vehicles and commanded by a " Host Chief" who reported directly to the head of the army corps.

Consequently, each army corps was assigned no less than two pedjets (500 tanks) which, between the four corps, made up the 2,000 vehicles indicated by contemporary sources.

Although we must add to them the Amorite chariot units called ne'arin —which, like the foreign infantry units, did not belong to the army corps— it is necessary to say that many of the Egyptian chariots were still on their way when the battle began and they never got into combat. This is probably what happened with the chariots of the Ptah and Seth divisions. If this is the case, and they arrived when it was all over, those 1,000 chariots with their healthy and rested crews should have deterred the Hittites from trying to fight again.

Egyptian chariots had their axles at the rear end and their track was much greater than the width of the vehicle, which made them almost unsinkable and capable of practically turning on themselves, changing direction in a very short time. For this reason they were more maneuverable than those of the Hittites, although their inertia was not as great due to their lighter weight.

They were manned by only two men and not three like their enemies: the crews were made up of a seneny (archer) and the driver, kedjen, who also had to protect to the one with a shield. The lack of a third crew member was made up for with a foot infantryman who ran alongside the vehicle, armed with a shield and one or two spears. This soldier fulfilled the function of protecting the seneny if necessary, but mainly he was there to finish off the wounded that the tank ran over in its path —the worst thing that could happen to tankers was to leave enemies alive behind them, an angle from which they were completely defenseless.

Tactical Use

Unlike their enemies, who based their tactics on the use of heavy tanks, the Egyptian army was focused, since the Old Kingdom, on the coordination of numerous infantry units organized into their respective army corps. The assimilation between society and the state and the latter and the army allowed, since ancient times, generals to take advantage of the coordination, organization and precision capacity for their troops that the ancient pharaohs had achieved for the great masses of workers in their notable architectural projects. Also the administration and administration had been copied from the teams of workers who had worked on the pyramids of Giza.

The chiefs relied on highly mobile tank groups, but until the end of their civilization, the primary weapon and core of the army remained the infantry.

The function of the Egyptian chariots was to break through the enemy lines, previously forced open by the powerful bows of the infantry, overwhelming everything in their path. Apart from their shock capacity, they acted as powerful mobile fire platforms, trying to avoid, as far as possible, getting involved in close-order combat, where the heaviest enemy tanks had the advantage. This "hit and run" It was successfully implemented during more than three centuries of Egyptian warfare, and its versatility was realized when the infantry developed the tactic of the foot runner supporting each chariot and sacrificing the wounded. Security aboard the chariot was so good that most of them could slip in and out of the enemy ranks two or three times per battle with their seneny unscathed, multiplying the apparent number of chariots in the battlefield. battle.

Foreword

The declaration of war

There are credible arguments that indicate that the battlefield of Qadesh was chosen by mutual agreement between the two opposing commands. Amurru's defection in the winter of 1302 BC. C. was considered by the Hittites as a violation of the Seti-Mursilis treaty, and thus manifested itself to the court of Ramses on a diplomatic mission the following year.

Although there is no documentary evidence, indirect sources indicate that Muwatalli took all the necessary legal steps, such as formally accusing Ramses of having instigated the treason of his vassal Amurru, raising a contentious trial through a messenger who arrived at Pi- Ramesses in the early winter of 1301 B.C. C. That message, practically a verbatim copy of the one his father Mursilis had sent years before, concluded that, since the parties could not agree on the disputed territories, the legal dispute should be resolved by the judgment of the gods, that is, on the battlefield.

Egyptian approach march

Having exhausted all instances of peaceful negotiation, Ramses II assembled his army in the two large military bases of Delta and Pi-Ramesses. On the ninth day of the second summer month of 1300 B.C. C. (see the question of dates), his troops passed the border city-fortress of Tjel and entered Gaza by way of the Mediterranean coast. From there, it took them a month to reach the intended battlefield, under the walls of the citadel of Qadesh. Pharaoh was at the head of his forces, riding his war chariot and wielding his bow. [citation required]

The four army corps marched by different routes: the Poem carved on the walls of the Karnak temple says that the First Corps went towards Hamath, the Second towards Beth Shan and the Third through Yenoam. Certain modern historians have used this circumstance to blame Ramses for the surprise suffered by the first two in the first phase of the battle, but other authors, such as Mark Healy, assure that sending the armies by various routes was a normal practice and adjusted to the military doctrines of his time (see controversy about it).

The First and Second Corps advanced along the eastern bank of the Orontes, while the remaining two followed parallel routes along the west bank, between the river and the sea. The Poem supports this theory in its verse which says that Ptah "...was south of Aronama". This city was, in effect, on the western shore. This allowed Ptah's Corps to rush immediately to the support of Amun and Sutekh, without the need to waste precious time fording the wide river.

Eve of the Battle

American archaeologist and Egyptologist Henry Breasted identified more than 100 years ago the place where Ramses established his initial camp, the 150m hill called Kamuat el-Harmel, located on the right bank of the Orontes. The king woke up there, accompanied by his generals and his sons, on the morning of the 9th day of the third month of the summer of 1300 BC. c.

Shortly after sunrise, Amun's Corps broke camp and headed north over terrain deemed "their own" to reach the agreed battlefield (the plain under Qadesh). The march, although difficult, had the advantage that many of the veterans knew the way, since they had done it previously under the command of Seti I (like the king himself, who had accompanied his father in the operation) or in the Ramesses's previous campaign.

The Army Corps of Ptah, Sutekh, and P'Ra followed, about a day away, and the Ne'arin Amorites with their chariots had not yet arrived either. It is legitimate to suppose that Pharaoh intended to camp in front of Qadesh and wait a few days for the rest of his forces.

The army corps, commanded by the monarch, spent the whole morning descending the mountain on which it stood, crossing the Robawi forest and beginning the fording of the wide and deep Orontes some 6 km downstream from the village of Shabtuna, identified today with the hill of Tell Ma'ayan. Nearby was also the village of Ribla, where Nebuchadnezzar II would locate, centuries later, his command post to besiege Jerusalem.

Amun's Corps and its supply train were larger than any of the other three, so the Orontes crossing must have lasted from mid-morning to mid-afternoon. Shortly after crossing the river, Pharaonic troops captured two Bedouin shasu, who were brought before Ramses for questioning.

To the God King's delight, the prisoners claimed that Muwatalli and the Hittite army were not in the Qadesh plain as feared, but were instead in Khaleb, a town north of Tunip. The War Bulletin accompanying the Poem states that the two men were instructed by the Hittites to supply the Egyptians with false intelligence, leading them to believe they had arrived first and therefore had the upper hand. However, it is quite naive to think that the Egyptians actually believed such informants or that such informants even existed.

Getting to the place of battle earlier was of enormous tactical importance in the Bronze Age, to the point that a difference of a few hours could define the course of a war. The enormous logistical difficulties of the time made it very difficult to prepare a huge army to fight, even more so when, as in this case, men and animals needed to have the opportunity to eat and rest after a forced 800 km march that had left them. taken more than a month. Learning that the Hittites were not there, Ramesses saw an opportunity to wait one day for the other three corps to face the enemy with his full force, even giving them two or three days to prepare.

Incredibly, not even the Egyptian sources mention that the pharaoh attempted to verify the information being offered, thus demonstrating his youth and inexperience. Contradicting the opinion of his most senior generals and eunuchs, Ramses gave the order for Amun to proceed immediately to Qadesh.

Arriving on the battlefield

The exact location of the Egyptian camp on the battlefield has not been pinpointed, but there was only one spot with potable water and easy to defend, so Ramses may have established it there. It is the same place where Seti had built his years before.

The camp was organized in the manner of a Roman camp, with the troops being ordered to dig a defensive perimeter that was later fortified with thousands of shields overlapping each other and stuck into the ground.

Foreseeing having to spend many days there, the base was conditioned to offer some comfort for a while: the temple of Amun was built in the center, a large tent was erected for Ramses, his sons and his entourage, and even Pharaoh's great golden throne, which had accompanied him all the way, was unloaded from a chariot.

The two shasu prisoners were beaten and subjected to other severe torture before being brought back before the king, who asked them again where Muwatalli was. They stood firm in their version. However, the punishments softened them somewhat, until they later recognized that they "belonged" to the king of Hatti. Thus, worries replaced Pharaoh's clear confidence. More beatings and more torture, and the Bedouin confessed what no one in the camp would have wanted to hear: 'Muwatalli is not in Khaleb, but behind the Old City of Qadesh. There is the infantry, there are the chariots, there are their weapons of war, and all together they are more numerous than the sands of the river, all ready, prepared and ready to fight. The old Qadesh was very close, a few hundred meters northeast of the promontory on which the city stood.

Ramesses understood that he had been deceived and that, in all probability, a total disaster was imminent: Ptah, Sutekh and P'Ra had to be warned of the situation, to reunite them with Amun as soon as possible. The initiative had now remained with the Hittites, so the sovereign sent his vizier to the south, to meet P'Re, to demand that he redouble the march. Although he has not been recorded, it seems reasonable that he sent another messenger north to hasten the arrival of Ne'arin Amorite units.

The Hittite Hideout

The Hittite army was indeed behind the walls of Qadesh the Old, but Muwatalli had established his command post on the northeastern slope of the tell (hill or promontory) on which Qadesh stood, a high position that, although it did not allow him to observe the enemy camp, did give him a clear intelligence advantage.

For unknown reasons, Ramesses released the two Bedouin spies rather than hold or execute them, and they naturally ran to supply information to their master. The Hittite king had also sent other advanced scouts to determine exactly where the enemy army was, and it can be established that at nightfall on the 9th of the third month (not before) the Hatti monarch had managed to gather all the information necessary.

It is said in the Bulletin that the Hittites attacked in the middle of Ramses's last meeting with his staff. If this is true, we have to believe that what is being described is a nocturnal assault. Although night attacks did exist, they were extremely rare, for several reasons: attacking blindly risked being ambushed, and carrying torches so as not to get lost made attacking troops easy targets for enemy archers..

Furthermore, Muwatalli could not attack before he had his intelligence, and it is proven that he could not have it before night fell. To make matters worse, his army was in Old Qadesh, so to attack Ramses in the dark his more than 40,000 infantry and 3,500 chariots must have forded the river without being able to see anything, which would have represented certain suicide. collective. In this way, modern sources feel authorized to affirm that the battle did not take place on that same day, but on the following day.

The Second Army Corps

The vizier of Ramses arrived at the bivouac of the Corps of P'Re, next to the Ribla ford, at dawn on the 10th. As is logical, nothing was yet ready: the soldiers were sleeping and the horses, manned, were unharnessed of the cars

Given the peremptory order to go immediately to the battlefield, the troops took down the tents, fed the animals and loaded the convoys with the impediment. This work had to last several hours.

The vizier changed the horses of his war chariot and instead of accompanying the Second Corps to the north, he headed further south to issue the same order to the Corps of Ptah, which was located south of the city of aronama.

It took the Second Corps a considerable time to ford the river, as the banks were churned up and trampled by the passage of Amun's Corps the day before, and military caution was apparently set aside by the urgency. The cohesion of the formations broke down on the opposite bank, and the army marched towards Qadesh at a double pace, possibly sending the chariots ahead.

First phase

Hittite attack

As the Second Corps quickened its pace northward, hastening towards Ramses's camp in compliance with the instructions brought by the vizier, it approached the banks of the Al-Mukadiyah River, a tributary of the Orontes that skirted the base of the mount where Qadesh was built and then ran south.

Visibility was very poor, because the weather had been dry for months and dust kicked up by thousands of feet and wagon wheels hung in the air and took a long time to settle.

The banks of the river were covered with vegetation, full of bushes, shrubs and even trees that did not allow the Egyptians to see the water or what was beyond.

When P'Ra was 500 meters from the river, surprise came: from the Al-Mukadiyah line of vegetation —to the right of the marching Egyptians— an enormous mass of Hittite war chariots emerged, throwing themselves on the column. The Egyptian chariots guarding the right of the line were overwhelmed and destroyed by the tide of vehicles, horses, and men that kept pouring out of the trees and showed no sign of ending. Launched at a gallop, the Hittite chariotists knew that they had to take advantage of the enormous inertia of their chariots, and further incited the beasts, which in a mad rush crushed the Egyptian right. Cutting through the ranks of infantry like fire, the Hittites continued west, smashing the chariots on the left and scattering the enemy, spearing them from the vehicles. The two lines of Egyptian chariots collapsed, their march formation—utterly inadequate to survive a sideline assault—disintegrated, and the few surviving infantry scattered to get out of range of the enemy pikes.

Egyptian discipline disappeared in the face of this surprise attack (see controversy), and before the last Hittite chariots had even emerged from the trees, the Second Army Corps was no more. Of the survivors, those in the lead hurried towards Ramses's camp, while the rear must have rushed south for the protection of the Ptah Corps approaching in the distance.

All that remained of the Egyptian formation was a bloody trail pulverized by chariot wheels and horse hooves, and several thousand corpses lying on the desert sands.

The Egyptian chariots in the vanguard dropped the reins and galloped north toward the camp to warn Ramses of the impending attack. Meanwhile, the Hittite chariots had reached the great plain to the west, of a size that would have allowed them to turn wide and turn back to hunt down the survivors. But instead of doing that, they turned north and headed to attack Ramses II's camp.

Assault on the Egyptian camp

Ramesses had arranged for several chariot units and infantry companies to stand guard, ready for action, inside the shield-enclosed enclosure. Despite the confidence that P'Ra and Ptah, in compliance with the vizier's urgent orders, would arrive later that day, and Sutekh the next day, and perhaps on the 12th the Ne'arin coming from the north from Amurru through In the valley of Eleutheros, many lookouts were stationed on the four sides of the camp, observing the distance. Their task was made difficult by the hot desert air that distorted the shapes and by the suspended dust that refracted the light.

The lookouts on the southern front shouted their alarms at the same time as those on the western side: while the former announced the frantic race of P'Ra's surviving chariots, the latter had just seen the huge formation of Hittite vehicles approaching threw towards them.

Even before the senenys of P'Ra entered the camp and began to explain what had happened, all the troops were ready for combat: in a few minutes, the Hittite chariots pounced on the northwest corner of the shield wall, they demolished it and entered the camp. The row of shields, the moat, and the many entangled tents, carts, and horses that they found in their path began to slow them down and make them lose their initial momentum, while the defenders tried to attack them with their khopesh swords in full swing. scythe shape The assault quickly degenerated into a savage melée hand-to-hand fighting. The Hittite chariots pushed each other because the interior space was not enough for everyone, so many of them could not enter and had to fight from outside the shield wall and defensive moat.

Many Egyptians died, and also numerous Hittites who, thrown from their chariots by collisions with their companions or fixed obstacles, were promptly slaughtered on the ground with a khopesh blow.

Pharaoh's personal guard (the sherdens) surrounded his tent, ready to defend the king with their lives. Ramses II, for his part —as the Poem informs us—, "put on his armor and took on his battle gear", organizing the defense with the sherden (who had chariots and infantry) and several other squadrons of war chariots that were stationed at the back of the camp (that is, on its eastern side).

The king's guard placed Ramesses's sons—among whom was the eldest of the sons, Prahiwenamef, who was then the heir to the throne since his two brothers had died in infancy—in safety at the eastern end, which had not been attacked.

Pharaoh donned the blue khepresh (crown) and, shouting orders to his personal (kedjen) driver, named Menna, mounted his battle chariot.

Ramesses organizes the defense

Bringing his bow and leading the surviving chariots, Ramesses II left the camp through the east gate and, turning north, circled it until he reached the northwest corner, where the Hittite chariots were bottled up in awkward confusion. and, therefore, almost defenseless. The invaders' attention was not drawn to the Egyptian chariots attacking them from the rear and left flank: they were absorbed in trying to break into the camp. Remember that Muwatalli had taken their pay from him, promising them only the part of the loot they could capture. Therefore, the first priority of the Hittites was to take what possible goods from the Egyptian camp, especially the huge and heavy golden throne of the pharaoh.

Their ambition lost them: the superior range of the Egyptian bows caused a great slaughter of the Hittite crews that had not yet made it inside, fixed targets that became easy prey for the experienced Egyptian marksmen. So crowded were the Hittites that disciplined Egyptian archers did not need to aim to hit a man or horse.

Slowly the Hittites reacted: spurring on their animals they tried to abandon the fight and flee across the western plain, in the opposite direction from which they had come. But their horses, unlike those of the enemy, were tired, and their chariots were slower and heavier. Those who gained the plain tried to spread out so as not to offer such an obvious target, but the Egyptian chariots launched in pursuit.

Many died under the khopesh of the menfyt as they fell from their chariots, which collided with others or overturned as they tripped over dead horses, and many others fell under the fearsome precision of enemy archers.

Within a few moments, the desert to the south and west of the camp was littered with corpses, to the point that Ramses exclaims in the Poem: "I made the field dyed. in white [referring to the long aprons worn by the Hittites] with the bodies of the Sons of Hatti".

The Hittites utterly defeated, with a few survivors scattered and fleeing, the menfyt proceeded methodically through the battlefield, finishing off the wounded and amputating their right hands. This method, shown many times as an example of the cruelty of the Egyptians, was actually an administrative device. The severed hands were delivered to the scribes, who, meticulously counting them, could make a reliable statistic of the enemy casualties.

Second phase

Hittite diversionary maneuver

According to the modern view of the battle, the fighting was not unfolding as Muwatalli had envisioned. In addition to the hasty action of pounced on the marching corps, the determined reaction of Ramesses and his chariots had put the Hittite vehicles to flight and now the Egyptians were pursuing the attacking chariots.

Muwatalli was to relieve the pressure on them by any means possible: he knew full well that the bulk of the Egyptian force had not even arrived (Sutekh and Ptah were still on their way to Qadesh) and his entire plan faced disaster.

Consequently, he chose to take action with a distraction maneuver that would allow him to recover the lost initiative, making part of the troops that were chasing his own return and forcing Ramses to return to his camp.

There were very few troops at the outpost where the Hittite king was located: apart from his personal entourage, he was accompanied by only a few trusted noblemen. Accordingly, he ordered them to organize a chariot force, cross the river, and attack the Egyptian camp from the eastern side.

The response was lukewarm (the nobility was not used to engaging in combat), but their emperor's blunt orders left little room for inaction. Thus, the most important men in the Hittite political hierarchy—including Muwatalli's sons, brothers, and personal friends—and from the commandos of his allies met in an ad hoc squad and, with difficulty, they crossed the Orontes towards the west.

The Ne'arin Arrive

No sooner had the camp been assaulted by this small force than the Hittite chariots were overwhelmed by a large chariot force coming from the north. It was about the Amorite chariots, the Ne'arin, which appeared providentially at that moment of Egyptian distress. Further behind came the Amurru heavy infantry. The report written on the walls of the funerary temple of Ramses, in Thebes, says verbatim in this regard: "The Ne'arin broke into the hated Children of Hatti. It was at the moment when they attacked the pharaoh's camp and managed to penetrate it. The Ne'arin killed them all.

Like a déjà vu from the first part of the combat, everything was repeated: the Amorites fired arrows at the Hittite chariots that were fighting to enter through a breach in the shield wall. When trying to turn back to get out of there and flee again to the relative safety of the eastern bank of the Orontes, another event occurred that sealed the Hittite fate: as they began to wade through the waters, some units of chariots returning from the south made their appearance from the south. the hunting and pursuit of the other force, accompanied by the advanced elements of chariots and infantry belonging to the Corps of Ptah that was present at the precise moment.

Death rained down on the Hittites on the road to the river, on the banks and even in the center of the water: many were shot by arrows, others were crushed by chariots, and most drowned as they were thrown from their vehicles, overwhelmed and dragged to the bottom by the weight of their armor.

Ramesses punishes his own

While the last of the Hittite chariots made their way to safety on their riverbank and the Egyptian infantrymen amputated the right hands of the fallen and packed them into sacks, Ramesses reoccupied the remains of his camp to await the arrival of Ptah and the return of the survivors of Amun and P'Ra.

Hittite prisoners, including high-ranking officers, nobles, and even royalty, were also brought there, and had to wait in silence for Pharaoh's decision on their lives.

The Poem says that Ramses received everyone's congratulations for his personal courage and daring in battle, and that he then retired to his tent and sat on his throne to "meditate. gloomily".

On the morning of the 11th, Ramses had the troops of the Corps of Amun and P'Ra line up in front of him. By summoning the captured Hittite dignitaries to witness the events, the pharaoh—perhaps personally—carried out the first historical antecedent of the punishment that the Romans would later call "tithing": counting by ten to his soldiers, he executed every tenth man as a lesson and example to others. The Poem describes it in the first person: "My Majesty stood before them, I counted them and killed them one by one, in front of my horses they collapsed and each one remained where they had fallen, drowning in his own blood...".

Although it cannot be said that the troops of Amun and P'Ra had fought with cowardice —remember that the marching columns were surprised by a force of chariots that, according to Ramses' own intelligence, should not have been there, and that In addition, it came out of a place out of sight -, today it is believed that they were punished for having violated the paternal-filial relationship that they were supposed to maintain with their lord.

In addition, it is very possible that such a lesson served the pharaoh's tactical purposes. Muwatalli's friends and relatives were, it is said, forced to witness the carnage, and then, released, rushed to bring their lord the news of the savagery of the Egyptians to his own troops. This was undoubtedly one of the factors that prompted the Hittites to sign the armistice later that same day.

End of Battle

With the high-ranking Hittite prisoners freed, Muwatalli's line of action became crystal clear. The main offensive force of his army—the chariots—had been destroyed, and likewise many chiefs and dignitaries had been killed in the Ne'arin attack.

He had not been able to exploit the tactical advantage of having arrived first on the battlefield as he had been forced to fight prematurely after his chariots' chance encounter with the Egyptian column, so it was clear that the battle had been lost.

Ramesses had, instead, two fresh and complete army corps, and the survivors of the other two strongly motivated by the summary executions they had just witnessed.

However, the Egyptian forces of Ptah, Sutekh, and Ne'arin were not enough to maintain Egyptian hegemony in the region, and the Hittite king realized this. Ramses' wishes to sustain himself as a power by retaining Qadesh had just vanished and, in these conditions of tactical defeat and possible strategic technical tie, the best thing to do was to request an armistice. Qadesh was left in Egyptian hands, but it was impossible that Ramses could stay there to take care of her. He should return to Egypt to lick the wounds of his heavy losses and it would represent the restoration of Hittite rule over Syria.

Therefore, Muwatalli sent an embassy to request the truce and Ramses, by accepting it, revealed to the Egyptians a weakness that would be confirmed by subsequent events.

Consequences

By proposing an immediate ceasefire, Muwatalli demonstrated his great intelligence. The armistice saved him losses, since shortly after Qadesh he had to send the remnants of his army to put down various rebellions in other parts of his empire.

Ramses and his army crestfallen returned to Egypt, booed and hissed contemptuously by every village they passed through. Adding to the humiliation, the Hittite troops followed the Egyptians to the Nile a few miles away, giving every impression that they were escorting a defeated and captive army.

The humiliation of the supposedly "victorious" Egyptian soldiers was so great that all parts of Syria that came under his rule after Qadesh rebelled against Pharaoh (some of them even before the army passed through on its march to Pi-Ramesses). All of them sought Hittite shelter and remained under its orbit for many years.

Though Egypt later recovered these regions, it took several decades to do so.

Immediately after Qadesh, a very long cold war followed between the two powers, a kind of unstable balance that ended sixteen years later with the signing of the famous Treaty of Qadesh.

The Treaty of Qadesh —the first peace agreement in history and which is perfectly preserved, since one of its versions was written in the diplomatic language of the time, Akkadian (the other in Egyptian hieroglyphics), on plates of silver—describes in detail the new borders between the two empires. It continues with the oath of both kings not to fight each other again, and culminates with the final and perpetual resignation of Ramses to Qadesh, Amurru, the Eleutheros valley and all the lands surrounding the Orontes river and its tributaries.

Despite the severe human losses suffered at Qadesh, therefore, the final victory went to the Hittites.

Later, specifically in the 34th year of the reign of Ramses, the pharaoh and the Hittite king sealed and consolidated the state of affairs established in the Treaty through blood ties: Muwatalli's brother and new king Hattusili III sent his daughter to marry Pharaoh. Ramses II was 50 years old when he received her very young wife, and he was so pleased with her gift that he named her her queen, under the Egyptian name of Maat-Hor-Nefru-Re. Thus, some of Ramesses II's sons and grandsons were grandsons and great-grandsons of his great enemy, King Muwatalli of Hatti, although none of them is believed to have succeeded to the royal throne.

From Qadesh, Egypt and Hatti remained at peace for about 110 years, until in 1190 B.C. C. Hatti was completely destroyed by the so-called "Peoples of the Sea".

Visit to the battlefield

The battlefield can be visited today. The promontory on which the Qadesh citadel stood is today called Tell Nebi Mend and can be visited. The state of conservation of the ruins and the recreation of the environment are quite bad, although it is not difficult to reach it from Damascus.

However, the visit is not, nowadays, justified. Although various Assyrian artifacts have been unearthed, archaeological excavations are prohibited due to the existence of a tomb of a Muslim saint and a mosque just on top of the promontory and several other Arab tombs on the battlefield.

Controversies and obscurities

About the date of the battle

All sources agree that the battle began "on the ninth day of the third month of the summer of the fifth year of the reign of Ramses". This places the combat around May 27, 1274 BC. C. if the coronation year of Ramses II occurred in 1279 a. c.

Although it has been claimed that the conflict occurred between 1274 and 1275 B.C. C., there are scholars who estimate that it occurred in 1270 a. C. or even in 1265 a. C., although some modern sources, e.g. Healy (1995), date the battle to 1300 BCE. C., but many Egyptologists and scholars, such as Helck, von Beckerath, Ian Shaw, Kenneth Kitchen, Krauss and Málek, estimate that Ramesses II ruled for about 66 years, from ca. 1279 to 1213 BCE C., placing the date around the year 1274 a. c.

On the trajectories of the Egyptian armies

Much has been written about the alleged "error" of Ramses II when sending the four armies along different paths, and this decision has been attributed to the quasi-disaster suffered by the first two when they were surprised by the Hittite chariots on the first day of the battle.

However, there are strong military reasons for Pharaoh to do it this way, the main ones being the size of his armies and the aridity of the terrain to be traversed. These two circumstances made the logistics of supplies for the troops a big problem. It was about traveling from Egypt about 800 km to the north, through Canaan, until reaching Central Syria.

Although "the season when kings go to war" (the time when wars were agreed upon) was clearly circumscribed to the period after the wheat and barley harvests to give the vassal states time to collect large amounts of food for the army that would arrive later, once the friendly territory had been abandoned. Army corps would have been left to their own devices. The only way to transport the supplies would have been to form huge oxcart convoys, so slow that they would have delayed the entire force for months on end.

Each army had, then, once the limits of the empire had been crossed, to supply itself by requisitioning food from the enemy's vassals. Only in this way could the Egyptians reach the battlefield in good physical and moral condition.

If Ramses had sent the four bodies by the same route, the Second would have found, at a given point, only the devastation produced by the needs of the First. After him would come the Third, finding even less food, and it is very likely that the soldiers of the Fourth had starved to death. Ramses did not want to fight alone with a well-fed army corps and three others weak and starving, so he designed four parallel approach routes so that each corps would never find the great shortage produced by the one that faced it. would precede

About the duration of the battle

The only reference to specific dates mentioned in ancient sources is that of the Poem, which locates the camp of Ramses south of Qadesh on the morning of the 9th. After that there is no other chronological indication, which has led classical historians to assume that everything happened that same day 9.

This is highly unlikely, and the main obstacle is that the sources mention the fording of the river as if it were something that could be done in fairly short periods of time.

Geology and hydrology have shown that the width, depth and flow of the Orontes have not changed substantially in the last few thousand years, so the difficulties encountered today in fording it need not have been less. in times of battle.

Experiments have been made to reproduce the crossing of the river through the places where Ammon forded it first and the Hittites later. Modern Arab donkey carts were used, which have wheels of more or less the same size as the vehicles in question, and it has been seen that, just after leaving the shore, the water reaches higher than the axles. From this observation arises the affirmation that the Egyptian army (4,000 infantry and more than 500 chariots, not counting those for supplies) had to wait until late afternoon on the 9th. The spies were later captured, tortured, interrogated and released even later, so if you want to justify the Hittite attack once their king had the data, the entire battle of Qadesh occurred in the dark.

But even this assumption does not consider that the Hittites also had to cross the river in the opposite direction. It is no longer a single army corps, but the entire force, made up of more than 3,500 tanks and 40,000 men. Apart from the impossible circumstance that that huge mass of people waited patiently all day under the tremendous Syrian summer sun for the Egyptians to arrive, only to have to cross a wide river in the dead of night. Those who think so do not take into account that the crossing would have taken all night and more than half of the morning. Apart from the dead, drowned, and wagons lost during the crossing, the Egyptians would have surprised them still crossing at dawn, and possibly massacred them despite Hittite superior numbers.

That is why current theory states that the Hittite attack occurred on the following day, the 10th, and not on the night of the 9th.

Dispute over surprise Hittite attack

It is reasonable to assume that by the night of the 9th, Muwatalli knew the location of Ramses' camp but not how many soldiers it contained, and certainly had no way of knowing that the P'Ra Corps was approaching from the south, because even the column of dust that he raised on his march was hidden by the hill of Qadesh from the eyes of his own command post and of course from those of the lookouts posted on the walls of Qadesh the Old.

Although his army was fresh and alert, there are very good reasons to assume that neither the Hittite nor the pharaoh planned to begin an all-out battle at dawn the next day. They had not concluded the strict protocol that governed the battles of that time, an unavoidable procedure that had to be carried out before entering combat and that included the exchange of diplomatic delegations, parliaments, taking statements by scribes, etc.

Although this was the first time that the young Ramses entered battle, and therefore we do not know how he would have conducted himself before, it is clear that Muwatalli had always complied with the protocols of war with extreme legality. In all his previous interventions he had camped first, parleyed and then attacked in agreement with his enemy. In fact, the Hittites never used the wow factor, which they considered dishonorable and worthy of cowards. They viewed a surprise attack on an unsuspecting enemy as an illegitimate advantage. Hittite sources consider Muwatalli to be a great chief and an illustrious strategist, laurels that he would not have obtained if he had attacked the P'Ra Corps by surprise.