Battle of Ilipa

The battle of Ilipa was a military confrontation that took place during the Second Punic War, in the spring of 206 BC. C., between the legions of the Roman Republic, led by Publius Cornelius Scipio the African, and the army of the Republic of Carthage, commanded by Asdrúbal Giscón and Magón Barca. It took place in the vicinity of Alcalá del Río, a town identified with the Roman city of Ilipa, located on the right bank of the Guadalquivir river. There is a historiographical debate about the location of the battle, since some authors locate it on the left bank. The result was a decisive Roman victory that led to the Carthaginian retreat and the Roman conquest of Hispania.

Background

The audacious capture of Cartago Nova —Cartagena— by Scipio meant the loss, on the Carthaginian side, of the Levant, allowing the Romans to expand towards the Betis basin —Guadalquivir—, where they obtained the great victory of Baecula —Santo Tomé—, making it impossible to send reinforcements to Aníbal Barca in the Italian peninsula. In addition, shortly after they lost the silver mines of Cástulo —Linares—, which greatly reduced their ability to hire more mercenaries. After this defeat, they remained on the peninsula only 25,000 to 30,000 soldiers from Carthage, who were later reinforced by 20,000 men and elephants from Africa. The Punics had to stop the Roman advance or risked the Romans continuing to Africa, so they entrenched themselves in Bajo Betis, where the Sierra Morena was and the last sources of silver to pay for their troops.

Hanno the Elder and Mago Barca were sent to Celtiberia but Scipio ordered the legate Marcus Junio Silano against them, defeating them at Orongis with 3,000 infantry and 500 cavalry, scattering their allies, capturing Hanno and forcing Mago to flee to Gades —Cádiz— After this defeat, the Carthaginian forces fell to 35,000 or 38,000, of which 20,000 were in Bética, so they began to recruit Turdetans to replace the casualties suffered.

Scipio's first attempt to conquer Bajo Betis found that each city had a strong garrison and understanding that it would be very costly to take each town, he retired to his winter quarters in Tarraco —Tarragona. He decides that the best thing is to provoke a great decisive battle. There he remained until the following spring, leaving for Cástulo and then Baecula, joining Silano's troops and numerous Celtiberian allies contributed by Culchas, reguli, "regulus" who ruled 28 cities. Meanwhile, the Carthaginians began to concentrate their forces, previously dispersed in the cities, during the winter. This meeting point was Carmo —Carmona—, from where they marched to Ilipa.

The Carthaginians camped at Ilipa, a city located on the hills, with a plain in front of it perfect for battle. Scipio marched against them with the main body of his army, and when he reached the vicinity he camped on some low hills in front of them. his enemy.

Scipio refused to waste his time and forces in minor combat and sieges, leaving cities with enemy garrisons as he advanced through the Bastetania, probably along the north bank of the Betis. The Carthaginians crossed the river course through the current Vado de las Estacas, trying to stand between said crossing and the Roman camp, located on a hill today called Pelagatos, because it was the only way to protect the region's silver mines. Apparently the Punic commanders were determined to engage in a decisive battle.

Confronting forces

Carthaginians

The Carthaginian army had a vast numerical superiority according to ancient historians. The Greek of the second century B.C. C., Polybius, affirms that they had 70,000 foot soldiers, 4,000 mounted and 32 war elephants. The Greco-Roman of the second century, Appian, agrees on the number of infants but raises the horsemen and pachyderms to 5,000 and 36 respectively. The Roman of the 1st century BC. C., Tito Livio, says that the Africans had 50,000 foot soldiers and another 4,500 on horseback. However, he himself acknowledges that some sources raise the infantry to 70,000 but that there is a fairly accepted agreement regarding the cavalry. One modern source, the British Howard Hayes Scullard, reduces the size of the Carthaginian force to just 35,000 combatants. More than half of its strength had been recruited from the Later, especially from Baetica and Turdetania.

Romans

In 211 B.C. C., a product that Rome wanted to permanently maintain an army in Hispania, Gaius Claudius Nero landed in Tarraco with 10,000 infantry and 1,000 horsemen, equivalent to two legions. He came from Pozzuoli. To increase his contingent he armed the crew of his ships, so he could count on 13,000 soldiers. A year later, he was replaced in command by Scipio, who brought 12,000 reinforcements from Italy. The latter was joined by the remains of his father's and uncle's army, destroyed in Betis, and that it had equaled two legions before their defeat. Thus, before attacking Carthage Nova the Roman army in the peninsula could well have added 28,000 infantry and 3,000 cavalry. In fact, Polybius believes that the Romans had 25,000 soldiers of on foot and 2,500 on horseback at that site.

Livio affirms that Mandonio and Indíbil, during their rebellion, recruited 20,000 infantry and 2,500 horsemen in 206 BC. C. and 30,000 infantry and 4,000 cavalry the following year; they probably supplied a similar number of warriors during Scipio's campaign. This agrees with the idea of many modern scholars, who believe that more than half of Scipio's army was made up of allies from Celtiberia, in fact, it is mentioned that the legionnaires were too few to fight a battle, without However, they bore the brunt of the battle. Scipio is said to have hoped that Carthage's native allies would switch sides during the battle.

At Ilipa the Romans and allies, according to Appian, were three times outnumbered by their enemies. Instead, Scullard claims they had only 10,000 fewer soldiers than the Carthaginians. Livy claims there were 45,000 combatants in all. Polybius said there were 45,000 infantry and 3,000 cavalry.

Battle

Skirmishes

Seeing the Romans busy building their castra —camp— Mago and Masinissa decided to charge the bulk of the cavalry. Scipio, however, had foreseen this and concealed his own horsemen behind from a nearby hill, thus, when the Carthaginians and Numidians pounced on the works, the Romans attacked him by surprise, putting many to flight. A ferocious hail of projectiles fell on the Punics. After a close combat, the Africans they ended up giving in, at first withdrawing in order but under enemy pressure they dispersed, pursued by light infantry armed with javelins.

This made the Carthaginians more prudent and the Romans more secure. During the following days there were new skirmishes on the plain between the two armies until the Romans decided to fight decisively, when supplies stopped reaching their camp and the soldiers began to starve. At that time Scipio summoned his soldiers to perform rituals and sacrifices to get divine support and encourage them for battle.

Order of Battle

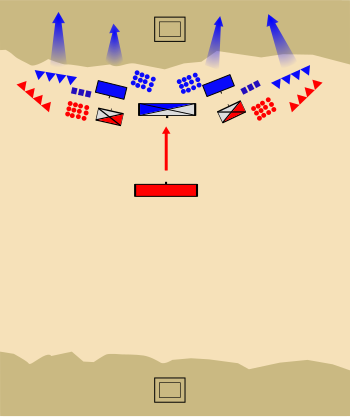

For days the Punics drew their troops in battle formation onto the plain and the Romans did the same, but neither attacked and they withdrew at sunset. Scipio had noted that Hasdrubal always formed up his men late in the morning, with the Libyan heavy phalanx in the center to face the legions and their Spanish allies in the wings with the elephants ahead.

For one night he provided written orders to leave the horses with their saddles on but covered. The next morning, he ordered his tribunes to give the soldiers breakfast at dawn and immediately marched out onto the plain in formation of battle. This was done with great alacrity, as the light infantry and cavalry approached the enemy outposts to hurl missiles at them. Their horsemen followed by the velites to fight at intervals, replacing each other. Soon after, at the beginning of the morning, the legions took up their positions on the plain but, contrary to the traditional order, the Spanish were in the center and the Romans in the alae, "wings".

Final Showdown

The Africans were completely surprised and had to hastily line up with their fasting soldiers. Hasdrubal, seeing the vanguard so close to his camp, ordered his cavalry and light infantry out to face it, attempting to lure the legions to the bottom of the hill while ordering the heavy cavalry to prepare for battle. His infantry marched out of the camp., forming up in the usual way. The clash of the light troops continued during the morning, they withdrew towards their lines and then returned to combat.

Finally, when they were less than a kilometer from the enemy, Scipio let his scouts through gaps between the maniples and ordered the frontal attack. These troops remained as reserves behind the Roman flanks. wing troops, commanded by himself —right— and Silano and Lucio Marcio Septimo —left—, having arrived at a certain distance, began to turn, both the foot soldiers and the mounted ones, always with the velites ahead and accelerating the attack. marches during this movement.

The legions in the wings collided with the enemy flanks. Meanwhile, their center, made up of Hispanics, advanced slowly without yet making contact. On the wings, the legionaries attacked while the Punics were flanked by the velites and light horsemen hidden in the rear and organized on each wing into three units of infantry. and as many cavalry. Thanks to this, a shower of missiles rained down on the elephants, who turned and fled, throwing their own ranks into disarray. The Roman horsemen defeated the Numidians because they cared to force a close combat, leaving them no room to retreat or throw their javelins. The Balearic slingers excelled in fighting the Romans on the flanks.

While the African wings were destroyed, the Libyans in the center, the best troops, did nothing. They couldn't help their comrades because if they left the center unprotected, the Hispanics in front of them would attack. The latter had received the order to advance slowly. The flanks resisted as best they could but as the sun reached zenith, the Carthaginians began to collapse due to exhaustion, heat and lack of food, something that affected the best fed and disciplined legionaries less. Meanwhile, in the center, where the fighting began much later, the Punics were already affected by fasting before the fight began, many holding onto their shields. Finally, Scipio himself, mounted on his horse, led the final charge. of his soldiers on all sides. The Africans tried to withdraw in order, defending themselves at every step, but finally succumbed and fled to the bottom of a hill. However, the Romans continued to pursue them and they ended up fleeing to their camp in the hills. They were not massacred there and the fortification captured by a providential storm that drove the legions back to their own camp.

Escape

The rain continued all night, but the vanquished did not rest, they were terrified because they knew that the legions would storm the camp at dawn, and they tried to improve their defenses by piling rocks. However, when the native warriors began to desert Hasdrubal decided to leave the position quietly in the dark.

Consequences

Retreat

Scipio's scouts informed him at dawn that the Africans had fled. Trying to overtake them before they crossed the Betis, they took another path and that prevented them from catching up, since Hasdrubal, upon learning that the Romans had reached the ford where he was going to cross the river, he diverted his way towards the coastal marshes towards Gades —Cádiz—. This did not prevent Scipio's infantry and light cavalry from permanently harassing his rear. Finally, the Carthaginians were immobilized by These attacks, allowing the legions to catch up with them, the terrain was narrow and made it difficult for the persecuted to move, possibly in the hills of Aljarafe, near Hispalis —Seville—, producing a massacre, saving barely 6,000 men.

Appianus says that they managed to reach a fortified city and Livy indicates that they built a makeshift camp on a hill. They were besieged for a few days and many deserted. Hasdrubal, after sending for ships on the nearby coast, abandoned his soldiers and fled at night to Gades by sea, embarking near Caura -Coria del Río. After learning of his flight, Scipio left the legate Silano in charge of the siege with 10,000 infantry and 1,000 horsemen and returned to Tarraco to meet with local leaders. Meanwhile, his legacy convinced Masinissa to return to Africa with his Numidians and change sides. Mago managed to reach Gades in ships sent by Hasdrubal, and the soldiers, abandoned by their officers, scattered. Silano went to Tarraco to unite with Scipio and they followed Cartago Nova. Apparently, the careful study of Apiano, Livio and Polibio allows us to affirm that both the battle and the entire Carthaginian retreat occurred north of Betis.

Sucro riot

Shortly thereafter, the victorious soldiers stationed in the Sucro camp mutinied. Scipio summoned his tribunes and told them that they must pay back wages from the taxes levied on local towns as soon as possible. He then dispatched the officers to the barracks to inform the soldiers. A day was set for everyone to meet and thus distribute the money, but when the date arrived, the general instructed the tribunes to be accompanied by the leaders of the mutiny, inviting them to their quarters. They were then arrested and a messenger was sent to the commander informing him of the success of the manoeuvre.

Later, after the soldiers had left their luggage at the gates of a nearby Spanish city, they were called to an assembly in the market and all attended. Scipio then had his most faithful troops surround the place and he appeared before the legionnaires, scolding them for their lack of loyalty to him and the country. He said that the lack of pay was not his fault and that mutiny was not the solution, but that they should have formally complained about the event. Later, he argued that a mutineer who was fighting to defend his land and his people could not be forgiven. He announced that the troops would be forgiven, with the exception of their leaders. being flogged, beheaded and dragged into the mass of legionaries. The rest of the soldiers, terrified, swore to their tribunes never to rebel again.

Analysis

Ilipa's victory is much like Cannae, a numerically smaller army engulfing a larger one thanks to the skill of its commander. The differences are that Scipio must have provoked the action by being more aggressive than Hannibal in the face of some Romans eager to attack him, and that the few Roman cavalry did not allow them to completely trap the enemy, allowing them to flee.

Meanwhile, Hasdrúbal Barca crossed the Pyrenees and headed for the Italian peninsula, where he would face his fate in the Metauro River.

Scipio refrained from taking hostages, which made him very popular with the natives, a policy he had followed since his victory at Baecula. Soon after, all of Carthaginian Spain was in his hands. He soon returned to Rome, covered in an aura of glory for his victories. Despite bringing great booty, numerous prisoners and even captured ships, the Senate denies him the right to a triumph for his victories for having fought as a privatus—he had no command of consul or proconsul, only general—and only received an ovation. Scipio had been elected with an imperium proconsulare only over his legions, but no legal power, although he himself propraetor, Silano, had subservient to his command.

After his departure, many formerly pro-Roman tribes and cities began to demand their independence. Among these were the Ilergetes, Ausetanos and Sedetanos from the Ebro basin -Iber. Despite the fight against Hannibal, the Senate sent reinforcements and by 201 BC. The situation was so calm that the garrison was reduced from two to one legion, discharging the rest. After the defeat of Macedonia, the senators decided to normalize the situation on the peninsula and appoint two praetors to govern it. In 197 BC. C. the conquered territory was divided into two provinces: Hispania Citerior and Ulterior. Each praetor had 8,000 legionaries and 400 horsemen, all Italic partners, to maintain order. Only in 196 BC. C., after the death of the praetor Cayo Sempronio Tuditano and the annihilation of his army in a revolt, the Roman contingent in the peninsula increased to 30,000 men, equivalent to four legions plus allies.

The Roman general, by executing the leaders of the mutiny at Sucro but increasing the pay of the common legionaries at the expense of his Spanish allies, began the process of turning those legions into his personal army. Scipio was probably the first from a long list of charismatic, wealthy and successful commanders who were able to challenge the collective power of the Senate. However, senatorial power remained strong and the Romans continued to steer clear of private armies despite examples of new warlords mobilizing their own peasant clientele into arms, such as Scipio Aemilius; its legions continued to be independent landlord peasant citizen militias. competition among the Roman elite would lead to the downfall of that collegial power.

Contenido relacionado

972

Saddam Hussein

1070