Battle of Ayacucho

Territories under realistic control.Territories under control of separatist movements.Territories under the control of the Great Colombia.Spain under French occupation.Spain during the liberal revolution.Zones without a clear government.

The Battle of Ayacucho was the last major confrontation included within the land campaigns of the Spanish-American wars of independence in South America (1809-1826) and meant the consolidation of the independence of the Republic From Peru.

The battle took place in the Pampa de Quinua in Ayacucho, Peru, on December 9, 1824 and the victory of the patriots meant the disappearance of the most important royalist military contingent still standing, and sealed the independence of Peru with a military capitulation that put an end to the resistance of the troops of the viceroy of Peru.

This event is usually referred to as the end of the wars of independence in South America, despite the fact that the Spanish garrisons of Real Felipe del Callao and Chiloé resisted until 1826 and Spain did not formally renounce the sovereignty of its American continental possessions until a decade later, in 1836. The treaty of peace, friendship and recognition with Peru was signed on August 14, 1879 in Paris.

Background

The liberating currents of America of 1820-1823

In the year 1820, Spain entered a political crisis due to the military uprising of the Spanish army led by General Rafael del Riego against King Ferdinand VII with the aim of restoring the Spanish Constitution and the liberal government. The uprising and rebellion of Rafael Riego in Andalusia in 1820 disintegrated and dispersed the expeditionary troops gathered for the Great Expedition, with this the threat of Spanish invasion of the Río de la Plata and Venezuela disappeared, and consequently in these regions the realistic resistance. This made possible the convergence of the liberating currents from South America to Peru.

The rebellion prevented the embarkation of the expedition of 20,000 soldiers and ten powerful warships to assist the royalists in America. This uprising destroyed the Spanish naval squadron and forever put an end to Spain's reinforcement expeditions, which since then have not been prepared for any place in America. The Spanish military uprising motivated the two great viceroyalties, of Peru and New Spain, which until now had contained the advance of the Spanish-American revolution, to take the path of independence. In North America, the viceroyalty of Mexico, with an almost defeated insurgency that is attracted to the new trigarante movement, is constituted as an independent monarchy through the Plan of Iguala and the pact of the three guarantees. And after defeating Viceroy Apodaca, the trigarantes were unable to agree on a peaceful separation with Liberal Spain, through the Treaties of Córdoba, which were rejected, and the Spanish attempts to reconquer Mexico continued until they gave up in 1829.

In South America, the uprising of Rafael del Riego had eliminated the threat of invasion of Venezuela and the Río de la Plata, and this allowed the advance of the Liberating Currents of America towards Peru. Viceroy Joaquín de la Pezuela had been discredited by the defeat of Mariano Osorio's expedition in Chile, the maritime isolation, and the invasion of José de San Martín's Liberating Expedition of Peru, which managed to surround Lima in the Cerro de Pasco and causes the desertion of Numancia. This succession of defeats determined the isolation of the Peruvian viceroyalty and Pezuela was overthrown by the Spanish general José de la Serna on January 29, 1821 in the military coup of Aznapuquio. La Serna left Lima with an army in full disintegration to take refuge in the Peruvian mountains without being hardly bothered.

But the Royal Army of Peru, under solid military subordination, reorganizes itself without any outside help and manages to destroy successive independent armies. The first are the troops under the command of the patriots Domingo Tristán and Agustín Gamarra who were ambushed in the battle of Ica. A year later, with José de San Martín retired after the Guayaquil Interview, the Liberating Expedition led by Rudecindo Alvarado was annihilated in the Torata and Moquegua campaigns. The year 1823 ended with the destruction of another patriot army commanded by Andrés de Santa Cruz and Agustín Gamarra, in another open campaign on the Intermediate Ports, which began with the battle of Zepita in Puno, and the occupation of the city of La Paz on August 8, managing to reach Oruro in Upper Peru. Viceroy La Serna, in this campaign nicknamed the "Talón", pursued the troops of Santa Cruz who ended up disbanded, and recovered Arequipa after defeating Antonio José de Sucre, who reembarked the Colombians on October 10, 1823.

Finally, what remained of optimism was extinguished by the seizure of the government by the Grancolombian leaders, under conspiracies and accusations of treason against the Peruvian presidents José de la Riva Agüero and José Bernardo de Tagle. Riva Agüero deported deputies from the Peruvian Congress and organized a parallel congress in Trujillo, and after being declared guilty of high treason by the Peruvian Congress he was exiled to Chile. On the other hand, Torre Tagle sought to sign a peace without battles with Viceroy La Serna, for which he went to meet with the royalists. This act was considered by Simón Bolívar as treason. Tagle ordered that all the forces under his command support Bolívar to face the enemy, while he sought to capture him to shoot him. José Bernardo de Tagle found refuge with the royalists in the besieged fortress of Callao.

However, the uninterrupted chaotic Spanish situation, the Liberal Triennium, the Royalist War (between absolutists and liberals) and the occupation of the French army of the One Hundred Thousand Sons of Saint Louis, which would remain until 1828 occupying Spain to support the king Fernando VII, would make it impossible to send any military reinforcement or any diplomatic conciliation. Thus, at the end of 1823, despite the resounding triumphs of the Peruvian royalists in the previous events of arms, the outlook appeared bleak for defenders of the integrity of the monarchy. The newly arrived Bolívar wrote diligently requesting reinforcements from Gran Colombia, and actively prepared what would be the definitive campaign against the Royal Army of Peru. The critical situation was beginning to become insurmountable for the supporters of the king's cause:

"..The virrey the Serna, for his part, without direct communications with the Peninsula, with the most melancholy news of the state of the metropolis... and therefore reduced to his own and exclusive resources but relying notably on the decision, in union, in loyalty and in the fortune of his subordinates, also accelerated the reorganization of his troops and was fastened to the next struggle. One more victory for the Spanish weapons in that situation would again wave the Spanish pavilion with inmarcessible glory to Ecuador itself; but another very different fate was already irrevocably written in the books of destiny.."Gnrl. Andrés García Camba.

The events of 1824

Truce in Buenos Aires and mutiny in Callao

The historian Rufino Blanco Fombona says that "Still in 1824 Bernardino Rivadavia made a pact with the Spanish, thus hindering the Ayacucho campaign": On July 4, 1823, Buenos Aires concluded a truce with the Spanish commissioners (Preliminary Peace Convention) that obliged it to send negotiators to the other South American governments so that it could take effect. It was stipulated that hostilities would cease 60 days after its ratification and would persist for a year and a half, while a definitive treaty of peace and friendship would be negotiated. For this reason, Juan Gregorio de Las Heras met in the city of Salta with Brigadier Baldomero Espartero, without reaching any agreement. Among other measures taken by the viceroy to contain his imminent rebellion, on January 10, 1824, Olañeta was ordered:

I warn V.E. that there should be no expedition in any direction on the provinces below without express order of mine because in Salta they are gathered to try to negotiate, General Las Heras by the Government of Buenos Aires and the Brigadier Espartero by that of this superior government (...)

Rivadavia believed that the project would establish peace and paralyzed the efforts of the Salta authorities on Upper Peru, denied aid and withdrew the outposts, damaging the cause of Peru.

In this regard, the historian and military man of Irish origin Daniel Florencio O'Leary said that with this truce "Buenos Aires has implicitly withdrawn from the conflict", and that "the Government of Buenos Aires makes an agreement with the Spanish, to the detriment of the American cause".

On January 1, 1824, Bolívar fell seriously ill in Pativilca. On those dates, Félix de Álzaga, plenipotentiary minister of the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata, arrived in Lima to ask Peru to adhere to the truce, which was rejected by the Peruvian Congress. But also from February 4, 1824, the Callao garrison revolted, made up of the entire Argentine infantry of the Liberating Expedition, along with some Chileans, Peruvians and Colombians: nearly 2,000 men, who also defected to the royalists. raising the Spanish flag and surrendering the fortresses of Callao. The Andes horse grenadier regiment also mutinied in Lurín on February 14, two squadrons headed to Callao to join the rebels, but upon learning that they had gone over to the royalists, a hundred of them with the leaders of the regiment They headed to Lima to join Bolívar. The corps was later reorganized by General Mariano Necochea by order of Simón Bolívar.

Faced with such events, the Minister of Colombia, Joaquín Mosquera, «fearing the ruin of our army» asked: «And what do you plan to do now? », to which Bolívar, with a determined tone, responded:

Triunfar!Simon Bolivar, Pativilca, 1824.

The Siege of El Callao prolonged the war until 1826, and it immediately led to the occupation of Lima by Canterac, and it is stated that in May 1824 with a military action against Bolívar "they would have given the last blow to the independence of this part of America.

Bolívar's withdrawal and the Olañeta rebellion

One week after the Callao mutiny, Bolívar ordered Lima to be abandoned, and from Huaraz, a general withdrawal of the Colombian army was launched in the direction of northern Peru, sending orders to his troops to regroup in Huamachuco (in the mountains) and Trujillo (on the coast). He ordered that the general withdrawal be carried out by devastating the Peruvian territory, cutting down the fields, kidnapping the livestock, and under a general scorched earth policy, destroying any resources of the Peruvian towns so that they could not serve as sustenance for the Royal Army of Peru. What Tomás de Heres had come to call “Colombian-style war”. In addition to the blood contribution, the free departments of Peru were required to pay the full salary of the Colombian army. Regarding the Peruvian navy, Bolívar from Trujillo gave orders to the head of the republican squad, Martín Guise, to throw He scuttled the patriotic ships of Callao that could not abandon it, among them the frigate Venganza or Guayas was lost, and he also ordered the captains of the Peruvian ships Limeña and Macedonia that were in the port of Guayaquil to be changed to Colombians.

Bolívar knew that Canterac's division was based in Jauja, parked waiting for the arrival of Jerónimo Valdés' division. And that together they would begin the offensive in the mountains, which would force Bolívar to prolong the retreat, and this would cause the disappearance of the Colombian army in Peru, and would endanger the south of Colombia up to the region of Pasto, still favorable to the Spanish monarchy in the Pasto campaign. Bolívar contacted his generals in Quito and his vice president in Colombia, warning them of the irremediable loss of Peru. The retreat plan was put into execution, with Bolívar in Trujillo and with the Colombian army in general retreat to the north, when Bolívar happily received the news of the Olañeta Rebellion.

The strategic map had changed decisively in favor of Bolívar. Surprisingly, at the beginning of 1824, the entire royalist army of Upper Peru revolted together with the Spanish absolutist leader Pedro Antonio Olañeta against the Viceroy of Peru, after learning that the Constitutional government had fallen in Spain. Indeed, the monarch Ferdinand VII of Spain and his absolutist supporters recovered the government supported by 132,000 French soldiers from the army of the Holy Alliance, who occupied Spain until 1828. Rafael del Riego died by hanging on November 7, 1823 and the promoters of the liberal movement were executed, marginalized or exiled from Spain. On October 1, 1823, the monarch decreed the abolition of everything approved during the three years of constitutional government, which provisionally suspended the appointment of La Serna as Viceroy of Peru. The scope of Spain's absolutist purge on the constitutional powers of the Viceroyalty of Peru seemed infallible.

Olañeta puts Upper Peru in rebellion, expels the Spanish chiefs loyal to the viceroy and leaves the loyal forces of the Peruvian viceroyalty without the support of the Upper Peruvian royalist army. Viceroy La Serna changed his plans to go down to the coast to defeat Bolívar, and on the contrary, he ordered Gerónimo Valdés to take the opposite direction, to the south, with a force of 5,000 veterans to cross the Desaguadero River and direct it to Potosí, against his former subordinate Olañeta, which was carried out on January 22, 1824. The Memoirs for the history of Spanish arms in Peru by the peninsular officer Andrés García Camba (1846) detail the disruption that the events in Upper Peru produced in the viceroy's defensive calculations. Valdés after a prolonged Alto-Peruvian military campaign, where the battles of Tarabuquillo, Sala, Cotagaita, and finally la Lava took place. i> On August 17, 1824, news of this domestic war was reported in which both royalist forces, of the Viceroyalty of Peru (liberals) and the provinces of Upper Peru (absolutists), decimated each other, losing leaders and veteran troops. that would be irreplaceable.

Bolívar meanwhile increased and reinforced his army with new regiments from Gran Colombia. In March 1824, fresh troops landed in Trujillo under the command of Brigadier General José María Córdova, whose action would decide the battle of Ayacucho, and for which he would be promoted to division general on the same battlefield; These were more reinforcements from Guayaquil, with him two new veteran battalions from Colombia arrived, and he immediately sent these brand new troops to reinforce General Sucre's army in the mountains. And so, in permanent communication with Olañeta, with whom Bolívar corresponded, took advantage of the dismantling of the royalist defensive apparatus to "move throughout the month of May against Jauja", and separately destroy José de Canterac's division, isolated in Junín on August 6, 1824. An incessant persecution then began with the consequent desertion and transfer of 2,700 royalist soldiers, who then swelled the independent ranks. Finally, on October 7, 1824, with his troops at the gates of Cuzco, Bolívar handed over command of the new battle front to General Sucre, which ran along the course of the Apurímac River, while he retired to Lima, according to Bolívar himself, to take more loans from the capital to sustain the war in Peru, and receive a new Colombian division of 4,000 men dispatched by Francisco de Paula Santander that would not arrive until after Ayacucho.

The Ayacucho Campaign

The destruction of Canterac's army in Junín forced Viceroy La Serna to call Jerónimo Valdés from Potosí, who came on forced marches with his soldiers. Once the royalist generals met, and despite signs of sincere support from Cusco, the viceroy ruled out a direct assault due to the lack of training of his militias, increased by massive recruits of peasants a few weeks before. On the contrary, his troops crossed the Apurimac River and tried to cut off Sucre's rear through maneuvers of marches and countermarchs, which followed one another from Cusco to the meeting in Ayacucho, along the Andean mountain range. In this way, the royalists sought a coup d'état that they obtained on December 3 in the battle of Corpahuaico or Matará, where at the cost of only 30 men they caused the liberating army more than 500 casualties and the loss of a good part of the park and the artillery. But Sucre and his staff managed to maintain the cohesion of the troops and prevented the viceroy from exploiting that local success. Even at the cost of significant losses in men and material, Sucre kept the United Army in an orderly withdrawal, and always located in secured positions, difficult to access, such as the Quinua field.

Another memoir, In the service of the Republic of Peru by General Guillermo Miller, offers the vision of the independentistas. In addition to the talent of Bolívar and Sucre, the United Army was nourished by a good part of the military experience of the century: the Rifles battalion of the Colombian army was composed of European mercenary troops, which in Most of them were British volunteers. This unit suffered considerable casualties in Corpahuaico. Also among its ranks were veterans of the Spanish and North American Independence, and the Spanish-American Wars of Independence, including cases such as the German major Carlos Sowersby, a veteran of the Battle of Borodino against Napoleon Bonaparte in Russia.

The royalists had consumed their resources in a war of movement without having managed to cut the lines of the liberating army. Due to the extreme harshness of the conditions of a campaign in the Andean mountain range, both armies were left with the number of their troops seriously reduced due to illness and desertion, which affected the independents to the same degree, and which also focused on militias lacking military training or recruitment formed from enemy prisoners. The royalist leaders had positioned themselves on the heights of the Condorcunca hill (in Quechua: condor's neck), a good defensive position but one that they could not maintain given that in less than five days they would be forced to withdraw due to the starvation of the troops, which which amounted to the dispersion of their army, while the Republicans waited for the arrival of more Colombian divisions; which is why the royalists were driven to make a desperate decision: the battle of Ayacucho began.

Order of battle

There is a debate around the difference in size and composition of the combatant armies.

Regarding the number of combatants, Sucre exaggerates his part in the battle, giving a reduced number of patriotic soldiers, whose number he takes at the end of the Ayacucho campaign, while overestimating the number of royalist soldiers, giving a number of soldiers before beginning the military campaign, and which is extracted from the Spanish military list captured with the number of men when leaving Cuzco. In reality, both armies began the Ayacucho campaign with a more similar initial state of strength (8,500 independent vs. 9,310 royalist). Both armies decreased in number as the campaign developed, until the day of the battle (5,780 independent vs. 6,906 royalist). On the battlefield, the royalists had 5,876 infantry and 1,030 cavalry.

About the composition of both armies, the royalist army was made up almost entirely of indigenous Peruvians, while the patriot army had more Europeans and foreigners in its ranks, with less than a quarter being Peruvians. However, the Peruvian Army established the day of the battle as its anniversary, in commemoration of the consolidation of the independence of Peru and South America.

"In this famous corner, a realistic army, composed in its entirety of natural soldiers of Alto and Bajo Perú, Indians, mestizos and white Creoles, and whose chiefs and officers did not reach the tenth part of the cash, fought with an independent army, of which the Colombians constituted the three quarters, the Peruvians less than a fourth, and the Chileans and porters a small fraction. On both sides ran Peruvian blood. There is no need to disfigure the story: Ayacucho, in our national conscience, is a civil battle between two sides, each attended by foreign auxiliaries. ".José de la Riva-Agüero

Liberating Army

- Commander: General Antonio José de Sucre

- Chief of Staff - General Agustín Gamarra

- Cavalry – General Guillermo Miller

- First Division - General José María Córdova (2300 men)

- Second Division General José de La Mar (1600 men)

- Reservation General Jacinto Lara (1700 men)

Before the start of the battle, General Sucre harangued his troops:

"Soldiers, today's efforts depend on the fate of South America; another day of glory will crown your admirable constancy. Soldiers: Long live the Liberator! Long live Bolivar, Salvador of Peru!Antonio José de Sucre

Our line formed an angle; the right, composed of the Bogotá, Boltijeros, Pichincha and Caracas battalions, of the first division of Colombia, in command of General Córdova. The left of the battalions 1.° 2.° 3.° and Peruvian legion, with the Husars of Junin, under the illustrisimo General La Mar. To the center, the granaries and husares of Colombia, with General Miller; and in reserve the battalions Rifles, Vencedor and Bargas, of the first division of Colombia, under the command of General Lara.Part of the Battle of Ayacucho

Note that Marshal Sucre omits to mention the Horse Grenadiers of the Río de la Plata in the report. General Miller in his Memoirs of General Miller: in the service of the republic of Peru gives the complete composition of the forces under Sucre's command:

Cordova Division (on the right): Bogota, Caracas, Voltigeros, Pichincha.Caballeria, Miller (to the center): Husares de Junín, Granaderos de Colombia, Husares de Colombia, Granaderos a Caballo de Buenos Aires.

Division Lara (on reservation): Vargas, Sellers, Hunters.

Division La Mar (left bow): Legion, No. 1, No. 2, No. 3.

Miller's statement that the Junín Hussars were in his division contradicts what Sucre says in the report.

Royal Army of Peru

- Commander: virrey José de la Serna

- Cavalry Commander – brigadier Valentín Ferraz

- Chief of Staff – Lieutenant General José de Canterac

- Vanguard Division - General Gerónimo Valdés (2006 men)

- First Division - General Juan Antonio Monet (2000 men)

- Second Division - General Alejandro González Villalobos (1700 men)

- Reserve Division - General José Carratalá (1200 men)

The Spaniards quickly lowered their columns, passing to the left-hands the Cantabrian battalions, Centro, Castro, 1 Imperial and two squadrons of húsares with a six-piece battery, forming too much their attack on that part. On the center were formed the Burgos, Infante, Victoria, Guides and 2nd battalions of the first Regiment, supporting the left of it with the three squadrons of the Union, the San Carlos, the four of the Guard Granaderos and the five artillery pieces already located; and on the height of our left the battalions 1 and 2 of Gerona, 2nd Imperial, 1st of the first Regiment, the Fernandinos,

Europeans in the army of Viceroy La Serna

The number of native Spanish soldiers who fought in Ayacucho has been limited by the same testimonies after the war. In the year 1824, the Europeans fighting throughout the viceroyalty amounted to 1,500 according to Brigadier García Camba, while according to the royal commissioner Diego Consul Jove Lacomme, an officer of the Olañeta rebel, the total number of Europeans was 1,200, and of those only 39 men were in the Upper Peru division.

By December 9, the day the battle of Ayacucho was fought, and according to later publications, the Europeans in the viceroy's army were approximately 500 men according to García Camba, while Bulnes cites 900 in the book "From the viceroy to the last cornet", relying on the diary of Captain Bernardo F. Escudero y Reguera, officer of the General Staff of Valdés. But the testimony of General Jerónimo Valdés refutes and corroborates the figure of 500 men "from soldier to chief".

Of the aforementioned number of royalist prisoners captured after the battle of Ayacucho, 1,512 were American, while 751 were Spanish, which means that the number of combatants peninsulars under the command of viceroy La Serna may be around that figure, since Spanish was then an imprecise term, synonymous with white, and the same was given to peninsular, Creole and any European.

The battle

At 8 in the morning, Monet advanced to the patriot positions and proposed to Córdova that, since in both armies there were leaders and officers linked by friendship or kinship, "we should give each other a hug before breaking our necks." With the authorization of Sucre, the officers greeted each other chivalrously.

A. Realistic positions at night from 8 to 9

B. Preparatory maneuver for realistic attack

C. March of battalions led by Colonel Rubín de Celis

D. Maniobra and attack of the Monet division

E. Attack of the vanguard of Valdés on the house occupied by the independentists

F. Charge of realistic cavalry

M. Advance and dispersion of the battalions of Gerona part of the realistic reserve

K. Battalion Fernando VII, last realistic reserve

The device organized by Canterac's plans envisaged that Valdés' vanguard division would surround the enemy group alone, crossing the Pampas River to anchor the units on the left of Sucre on the ground, which was carried out in the first phase of the battle. Meanwhile, the rest of the royalist army descended frontally from the Condorcunca hill, abandoned its defensive positions and charged against the bulk of the enemy whom it expected to find disorganized. The Gerona and Fernando VII battalions would remain in reserve, ready in the second line to be sent wherever they went. required.

Sucre immediately realized the risky maneuver, which was evident to the extent that the royalists were on a slope, unable to camouflage their movements. The Spanish colonel Joaquín Rubín de Celis, who commanded the First Regiment of Cuzco, and who had to protect the location of the artillery, which was still in pieces and loaded on his mules, impetuously advanced to the plain very prematurely, incorrectly interpreting direct orders from the Viceroy "threw himself alone and in the most reckless manner into the attack" where his unit was destroyed and he himself was killed in the decisive counterattack by the Córdova division, which then advanced in compact line formations, and which with effective fire also pushed back the dispersed riflemen of the Villalobos division, which had just descended. in Guerrilla formations. Córdova's division, supported by Miller's cavalry, directly attacked the disorganized mass of royalist troops that, unable to form for battle, descended in rows from the mountains. It was in this attack that General José María Córdova uttered his famous phrase < i>"Division, weapons at discretion, front, step of victors".

Seeing the disaster that his left had suffered, General Monet, without waiting for his cavalry to form on the plain, crossed the ravine and at the head of his division he attacked Córdova's division and managed to form in battle i> to two of his battalions but soon attacked by the independence division he was surrounded before the rest of his troops could also form in battle. During these actions Monet was wounded and three of his leaders were killed. Those dispersed from his line dragged the masses of militiamen into their retreat from him. The royalist cavalry under the command of Ferraz charged the enemy squadrons that were harassing Monet's left, but supported by the lively fire of their infantry, they caused an enormous number of casualties among Ferraz's cavalrymen, whose survivors were forced to turn their backs and withdraw from the battlefield.

At the other end of the line, the second division of José de La Mar supported by the Vargas battalion of the third division of Jacinto Lara together stopped the attack of the veterans of the Valdés vanguard who had launched themselves to take the lonely house occupied by some pro-independence companies, which were initially overwhelmed and forced to retreat, and would be reinforced by the charge of the Junín Hussars under the direction of Miller and then by the horse grenadiers they returned to the attack, which was The victorious Córdova division would later be added.

Viceroy La Serna and other officers tried to reestablish the battle and reorganize the dispersed people who were fleeing and General Canterac himself led the reserve division on the plain. However, those recruited from the Gerona battalions were not the same as those who had won in the battles of Torata and Moquegua, since during the Olañeta rebellion they had lost almost all of their veterans and even their former commander Cayetano Ameller. This troop made up of soldiers forced to fight dispersed before facing the enemy, followed after weak resistance by the diminished Fernando VII battalion. At one in the afternoon the viceroy had been wounded and taken prisoner along with a large number of his officers, and although Valdés' division continued fighting on the right of its line, the battle was won for the independentistas. The casualties confessed by Sucre were 370 dead and 609 wounded, while the royalist casualties were estimated at 1,800 dead and 700 wounded, which represents a high mortality rate in combat.

With the decimated remains of his division Valdés managed to retreat to the heights of his rear where he joined 200 cavalry who had gathered around General Canterac and a few scattered of the defeated royalist divisions whose demoralized fleeing soldiers even arrived. to shoot at the officers who were trying to regroup them. With the bulk of the royal army destroyed, the viceroy himself in the power of the patriots, and his enemy Pedro Antonio Olañeta occupying the rear, the royalist leaders opted for capitulation after the battle.

The capitulation of Ayacucho

"Don José Canterac, lieutenant general of the real armies of S. M. C., in charge of the superior command of Peru for having been wounded and imprisoned in the battle of this day the most excelent lord virrey Don José de La Serna, having heard the general lords and leaders who met after, the Spanish army, filling in every way how much he has demanded the reputation of his weapons in the bloody day of Ayacucho".

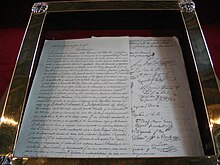

It is the treaty signed by the royalist chief of staff, Canterac, and General Sucre at the conclusion of the battle of Ayacucho, on December 9, 1824. Its main consequences were several:

- The realistic army under the command of the viceroy La Serna renounced the struggle.

- The permanence of the last realistic soldiers in the fortresses of Callao.

- The Republic of Peru had to settle the economic and political debt to countries that contributed militarily to its independence.

Bolívar called from Lima to the Congress of Panama, on December 7, for the unity of the new independent countries. The project was ratified only by Gran Colombia. Four years later, Gran Colombia, due to the personal desire of many of its generals and the absence of a unitary vision, would end up dividing into the nations they currently form.

The city of Cuzco would be taken by Agustín Gamarra's troops on December 24.

The lieutenant generals, viceroy José de la Serna and José de Canterac, marshals Gerónimo Valdés, José Carratalá, Juan Antonio Monet and Alejandro González Villalobos, brigadiers Ramón Gómez de Bedoya, Valentín Ferraz, Andrés García Camba, Martín de Somocurcio surrendered, Fernando Cacho, Miguel María Atero, Ignacio Landázuria, Antonio Vigil and Antonio Tur y Berrueta, 16 colonels, 68 lieutenant colonels, 484 majors or other officers and 2000 soldiers.

Theories about the Battle of Ayacucho

The capitulation has been called by the Spanish historian Juan Carlos Losada as "the betrayal of Ayacucho" and in his work Decisive Battles of the History of Spain (Ed. Aguilar, 2004), he states that the result of the battle was agreed in advance . The historian points to Juan Antonio Monet as the person in charge of the agreement: “the protagonists always kept a scrupulous pact of silence and, therefore, we can only speculate, although with little risk of being wrong” (Page 254). A capitulation without battle would undoubtedly have been judged as treason. The Spanish leaders, with liberal ideas, and accused of belonging to Freemasonry like other pro-independence military leaders, did not always share the ideas of the Spanish King Ferdinand VII, a monarch who was a firm supporter of absolutism.

On the contrary, the Spanish commander Andrés García Camba refers in his memoirs as how the Spanish officers later nicknamed "ayacuchos", were unjustly accused upon their arrival in Spain: "gentlemen, with that we lost masonically" they were told accusatory, -"That was lost, my general, as battles are lost. /i>, responded the veterans of the battle.

Against this Masonic theory is the fierceness of the battle, which is reflected in the high mortality of the officers and troops, mostly indigenous Peruvians, as well as the Spanish peninsular officers. Among the casualties suffered were those of colonels Francisco Cucalón, from Aragon, head of Infante Don Carlos, Joaquín Rubín de Célis, from Leon, head of the first regiment of Cuzco, Juan Lugo, from Burgos, the battalion commanders, Francisco Villabase, from first regiment, Francisco Palomares, of the first battalion of the Imperial Alejandro, and Francisco Brisvela, assistant to Field Marshal Monet, killed. Considerably or seriously wounded, Lieutenant Colonel José Fernández, of the Hussars of Fernando VII, and the commanders Francisco López, of the Dragoons of the Union, and of the same general staff José Manriques and Luis Raseti, and the same viceroy José La Serna e Hinojosa.

Alto Perú after the battle of Ayacucho

After the triumph of Ayacucho, and following precise instructions from Bolívar, General Sucre entered the territory of Upper Peru on February 25, 1825. His military campaign served to give legality to an independence process that the patriots themselves Alto Peruvians had already launched the guerrilla war in Alto Perú. Sucre also maintained civil order in the country and reestablished government administration in La Paz. The royalist general Pedro Antonio Olañeta remained in Potosí, where in January he received the & # 34; Unión & # 34; coming from Puno under the command of Colonel José María Valdez, and then convened a War Council that agreed to continue the resistance in the name of Fernando VII. Olañeta distributed his troops among the Cotagaita fortress with the & # 34; Chichas & # 34; under the command of Colonel Medinacelli, while Valdez with the "Unión" He was sent to Chuquisaca and Olañeta himself went to Vitichi, with 60,000 pesos of gold from the Potosí Mint.

However, Cochabamba revolted, with the First Battalion "Fernando VII" Colonel José Martínez; followed in Vallegrande, by the Second Battalion "Fernando VII", deposing the royalist brigadier Francisco Aguilera on February 12. The independence colonel José Manuel Mercado then occupied Santa Cruz de la Sierra abandoned by Aguilera on February 14, while Chayanta was left in the hands of Lieutenant Colonel Pedro Arraya, with the "Santa Victoria" and "American Dragons" and in Chuquisaca the "Dragones de la Frontera" Colonel Francisco López spoke out for the independentists on February 22, with which the majority of the royalist troops of Upper Peru gave up continuing the fight against the powerful army of Sucre. Colonel Medinaceli with three hundred soldiers also revolted against Olañeta and on April 1, 1825 they fought in the battle of Tumusla, which culminated in the defeat of Olañeta and his death the next day. A few days later, on April 7, General José María Valdez surrendered in Chequelte (Santiago de Cotagaita) to the patriotic General Urdininea, ending the war in Upper Peru.

The birth of Bolivia

Simón Bolívar, with the approval of the Peruvian congress on February 23, 1825 and of the Argentine congress on May 9, 1825, ratified the decision of Antonio José de Sucre to convene a sovereign congress of Upper Peru that he stated in his declaration of independence his desire not to join Peru or the United Provinces of Río de la Plata.

Through a decree the Assembly determined that the new state born in Upper Peru would bear the name "Bolivar Republic", in homage to the Liberator, designated "Father of the Republic." He was also granted the supreme executive power for life, with the honors of Protector and President. Bolívar was grateful for these honors, but declined to accept the position and appointed the Marshal of Ayacucho Antonio José de Sucre.

Declaration of independence of Bolivia

The Deliberative Assembly was convened again in Chuquisaca by Marshal Sucre, on July 9, 1825, and once concluded, the complete independence of Upper Peru was determined, under the republican form. Finally, the president of the Assembly José Mariano Serrano, together with a commission, drafted the "Acta de la Independencia" which is dated August 6, 1825, in honor of the Battle of Junín won by Bolívar. Independence was declared by 7 representatives from Charcas, 14 from Potosí, 12 from La Paz, 13 from Cochabamba and 2 from Santa Cruz. The independence act, drafted by the president of Congress, Serrano, in its expository part says:

The world knows that Alto Peru has been on the continent of America, the ara where it poured the first blood of the free and the land where there is the tomb of the last tyrants. The departments of Upper Peru, in their resolutive part, protest to the face of the whole earth, that their irrevocable resolution is to govern themselves.

Recognition of combatants

In honor and recognition of the independence fighters of the battle, an obelisk was built in 1974 at the site of the events in commemoration of the battle, the work of the Spanish artist Aurelio Bernandino Arias.

With a concrete structure and covered in white travertine marble, this monument is located in the historic Sanctuary of the Pampa de Ayacucho, in the district of Quinua, Province of Huamanga. 37 km northeast of the city of Ayacucho, 3300 m s. n. m.

Recognitions to Sucre

Bolívar, who wrote and published in 1825 his succinct summary of the life of General Sucre, the only work of its kind carried out by him, spared no praise for the culminating feat of his faithful lieutenant:

"The battle of Ayacucho is the summit of American glory, and the work of General Sucre. The disposition of it has been perfect, and its divine execution." Coming generations await the victory of Ayacucho to bless her and contemplate her sitting on the throne of freedom, dictating to the Americans the exercise of their rights, and the sacred empire of nature."

"You are called to the highest destinations, and I foresee that you are the rival of my Glory. (Bolívar, Letter to Sucre, Nazca, April 26, 1825)."

"The Congress of Colombia then made Sucre General in Chief, and the Congress of Peru gave him the rank of Gran Mariscal de Ayacucho."

The Battle of Ayacucho in popular culture

- The Colombian national anthem, written by Rafael Núñez, mentions this battle in the seventh verse.

- The battle is graphically narrated in the number 4 of the Mexican comic book Epopeya of September 1, 1958, entitled Ayacucho, the battle that liberated America.

Contenido relacionado

History of Logic

GM-NAA I/O

Hittite laws

Donation of Pepin

History of optics