Battle of austerlitz

The battle of Austerlitz, also known as the battle of the Three Emperors, pitted a French army led by Emperor Napoleon I against the combined Russo-Austrian forces of Russian Tsar Alexander I and Austrian Emperor Francis I in the context of the Napoleonic Wars. It was one of Napoleon's greatest victories, as the First French Empire definitively crushed the Third Coalition after almost nine hours of difficult combat. The battle took place near Austerlitz, present-day Slavkov u Brna, about 10 km southeast of Brno, in Moravia, then part of the Austrian Empire and today the Czech Republic. Austerlitz brought the war of the Third Coalition to a quick end and a few weeks later the Treaty of Pressburg was signed. The battle is considered a tactical masterpiece by Napoleon, on a par with Cannae or Gaugamela.

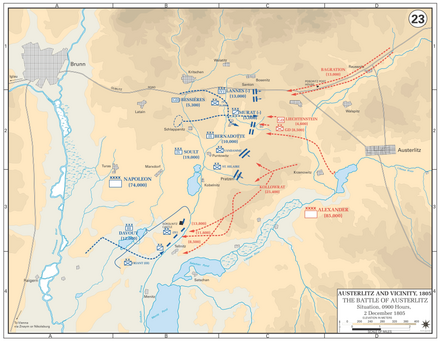

After eliminating an Austrian army at the Battle of Ulm, French forces succeeded in taking Vienna in November 1805. The Austrians avoided another clash until the arrival of the Russians gave them an advantage in numbers. Napoleon sent his army north in pursuit of the allies, but then ordered them to fall back in order to feign weakness. Desperate to engage in combat against the allied forces, Napoleon tried to demonstrate, in the days before the great confrontation, that his army was not in combat condition, going so far as to abandon a strategic position on the Pratzen hill near Austerlitz. He deployed the French army at the foot of Pratzen and deliberately weakened its right flank to incite the allies to attack him there and then surround them with the rest of his forces. The III Corps of the French army led by Marshal Davout had to make a forced march from Vienna to cover the gap left by Napoleon in time. Meanwhile, the forceful Russo-Austrian attack against the French right wing emptied its center in Pratzen, something that Marshal Soult took advantage of to attack fiercely with the IV Corps of the French army. With the center of the allies totally annihilated, the French swept both flanks of the enemy, forced their troops to flee in utter chaos and captured thousands of prisoners.

The Allied debacle hit hard at Emperor Francis' confidence in the British-led war effort. France and Austria immediately agreed to an armistice and shortly after, on December 26, the Treaty of Pressburg was signed, by which Austria was left out of both the war and the Coalition, while reinforcing the terms agreed in the previous treaties. of Campo Formio and Lunéville between both nations. This treaty also confirmed the loss of Austrian possessions in Italy and Bavaria to France, as well as Germany to Napoleon's German allies. An indemnity of forty million francs was also imposed on the defeated Habsburgs and the fleeing Russians were allowed free passage through hostile territory on their way to their homeland. On the other hand, the French victory at Austerlitz allowed the creation of the Confederation of the Rhine, made up of several German states that were to act as a buffer zone between France and Central Europe. The Confederation rendered the Holy Roman Empire virtually useless, so it collapsed in 1806 after Francis abdicated the imperial throne and retained the title of Francis I of Austria as sole officer. These changes, however, did not bring lasting peace to Europe. Prussia's concern over growing French influence on the continent would eventually lead to the outbreak of the War of the Fourth Coalition in 1806.

Foreword

Europe had been in crisis since the start of the French Revolutionary Wars in 1792. In 1797, after five years of conflict, the French First Republic subdued the First Coalition. A Second Coalition was formed in 1798, which was also defeated in 1801, leaving Britain the sole opponent of the French Consulate. In March 1802 France and the United Kingdom agreed to end hostilities with the Peace of Amiens, with which for the first time in ten years all of Europe was at peace. However, numerous problems persisted between both parties that made the implementation of the treaty increasingly difficult. The British government resented having to surrender most of its colonial gains since 1793, and Napoleon was furious that the British had not evacuated their troops from the island of Malta. The tense situation only worsened when Napoleon sent an expeditionary force to crush the Haitian Revolution. In May 1803 the United Kingdom declared war on France.

The Third Coalition

In December 1804 an Anglo-Swedish agreement led to the creation of the Third Coalition. British Prime Minister William Pitt spent 1804 and 1805 in intensive diplomatic activity aimed at forming a new coalition against France, and in April 1805 Great Britain and Russia signed an alliance. Having been defeated twice in recent times by France, Austria joined the coalition a few months later seeking revenge.

Forces

French Imperial Army

Prior to the formation of the Third Coalition, Napoleon had assembled an invasion force called the Army of England in six fields around Boulogne in northern France, intending to use it to attack the British Isles. Although they never set foot on English soil, Napoleon's troops received careful and valuable training for any military operation. Although boredom took its toll on the troops, Napoleon visited them on several occasions and made several colorful military parades to boost their morale.

The men of Boulogne formed the nucleus of what Napoleon would later call La Grande Armée. At first this French army numbered about 200,000 men organized into seven corps, which were large field units numbering 36–40 guns each and capable of independent action until other corps came to their rescue. only a well-placed corps in a strong defensive position could survive at least a day without support, thus giving the Grande Armée countless strategic and tactical options in each campaign. As a corollary to these forces, Napoleon created a cavalry reserve of 22,000 men organized into two cuirassier divisions, four mounted dragoons, one dismounted dragoons and one light cavalry, all supported by 24 artillery pieces. By 1805 the Grande Armée had grown to 350,000 men, generally well equipped, trained, and led by competent officers.

Imperial Russian Army

The Imperial Russian Army in 1805 retained many features of the Old Regime organization: it had no permanent formation above regimental level, high-ranking officers came mostly from aristocratic circles, and ranks were generally sold to the highest bidder, regardless of competition. The Russian soldier, in line with the practice of the 18th century century, was normally mistreated and punished "to inculcate discipline". Furthermore, many low-ranking officers were poorly trained and had difficulty getting their men to perform the sometimes complex maneuvers required in battle. On the contrary, the Russians had good artillery manned by soldiers who fought very hard to prevent their artillery pieces from falling into enemy hands.

The Imperial Russian Army's supply system depended on the local population and their Austrian allies, which provided up to 70 percent of their needs. Without an efficient and organized supply system and extensive supply lines, Russian soldiers found it difficult to stay healthy and combat ready.

Austrian Army

Archduke Charles, brother of the Emperor, had begun to reform the Austrian army in 1801 by removing power from the Hofkriegsrat, the military and political council responsible for decision-making in the armed forces. of Austria. Charles was the best field commander in Austria, but he was unpopular at the royal court and lost much influence when, against his advice, he decided to go to war against France. Karl Mack became the new main commander of the Austrian Army and introduced reforms to the infantry on the eve of the war that led to a regiment being made up of four battalions of four companies, instead of the previous three battalions of six companies. This sudden change was not matched by proper officer training, so these new units were not as well led as they could have been. The Austrian cavalry was considered the best in Europe, but the dispersal of its units into various formations infantry reduced their effectiveness against their massed French counterparts.

Preliminary movements

In August 1805 Napoleon, Emperor of the French since December of the previous year, turned his army's sights from the English Channel to the Rhine River in order to deal with the Austrian and Russian threats. On September 25, after a frantic and secret march, 200,000 French soldiers began to cross the Rhine on a 260 km front. Mack had assembled most of the Austrian troops at the fortress of Ulm in Swabia (today today southern Germany). Napoleon moved his forces north and made a roundabout move that put them in the rear of the Austrians. The maneuver was well executed and on 20 October Mack and 23,000 Austrian soldiers surrendered at Ulm, bringing the total number of Austrian prisoners in the campaign to 60,000. Although this spectacular victory was overshadowed by defeat of the Franco-Spanish squadron at the Battle of Trafalgar the next day, French successes on land continued with the fall of Vienna in November, where 100,000 muskets, 500 guns and several intact bridges along the Danube were captured.

Meanwhile, the delay in the arrival of the Russian troops prevented them from assisting the Austrian field troops, so they withdrew to the northeast to wait for reinforcements and to link up with the surviving Austrian units. Tsar Alexander I then appointed General Mikhail Kutuzov as Commander-in-Chief of the Russian and Austrian troops, who arrived on the battlefield on September 9, 1805 to collect information. He quickly contacted the Austrian emperor and his courtiers to discuss plans and logistical issues. Under pressure from Kutuzov, the Austrians agreed to supply ammunition and weapons in a timely and sufficient manner. Kutuzov also noted shortcomings in Austria's defense plan, which he called "very dogmatic." In addition, he opposed the annexation of the lands recently fallen under Napoleon's control, because this would make the local population mistrust the allies. However, many of Kutuzov's proposals were rejected.

The French continued to advance, but soon found themselves in an unenviable position: Prussian intentions were unknown and could be hostile, the Russian and Austrian armies had joined, and the French lines of communication were already extremely long and required strong forces. garnishes to remain open. Napoleon realized that the only logical way to achieve success at Ulm was to force the allies to fight and defeat them. On the Russian side, Commander-in-Chief Kutuzov realized this as well, so instead of clinging to the suicidal Austrian defense plan, he decided to withdraw. He sent Pyotr Bagration with six hundred men to hold off the French in Vienna and instructed the allied army to accept Murat's ceasefire proposal and thus have more time for withdrawal. Napoleon soon realized Murat's mistakes and ordered him to pursue them, but by then the allies had already withdrawn to Olmutz. According to Kutuzov's plan, the allies would withdraw further, into the Carpathian region and, in his words, "in Galicia, I will bury the French".

However, Napoleon did not stand still. The French emperor decided to set up a psychological trap in order to attract the allies. Days before any fighting, Napoleon had given the allies the impression that his army was in a weak state and that he desired a negotiated peace. Only about 53,000 soldiers, including the forces of Soult, Lannes, and Murat, would take possession. from the path of Austerlitz and Olmutz, attracting the attention of the enemy. The allied forces, numbering 89,000 men, would appear to be vastly superior and could attempt the attack. Unbeknownst to the Allies, however, reinforcements from Bernadotte, Mortier, and Davout were already within supporting range and could be called in from Iglau and Vienna, respectively, increasing the French forces to 75,000 troops and reducing the inequality in numbers.

The pull plan didn't stop there. On November 25, the French General Savary was sent to the Allied headquarters at Olmutz in order to secretly examine the situation of the Allied forces and deliver a message expressing Napoleon's desire to avoid a battle. Unsurprisingly, this was seen as a sure sign of weakness. When Francisco I offered an armistice on the 27th, Napoleon expressed great enthusiasm in accepting it. On the same day, Napoleon ordered Soult to abandon both Austerlitz and the Pratzen Heights and also to create a picture of chaos during the retreat, which would cause the allies to occupy the heights. The next day, November 28, the French emperor requested a personal interview with Alexander I, after which he received a visit from the tsar's most impetuous aide, the kniaz Piotr Dolgorúkov. The meeting was part of the deception, as Napoleon intentionally expressed anxiety and doubt to his adversaries and Dolgorukov reported everything to the tsar as a further indication of French weakness.

The plan succeeded. Many of the Allied officers, including the Tsar's aides and the Austrian chief of staff Franz von Weyrother, strongly supported the idea of attacking immediately and apparently influenced the Tsar's opinion. Kutuzov's idea was rejected and the Allied forces fell into the trap that Napoleon had created.

The Battle

Napoleon was able to muster some 72,000 men and 157 guns for the impending battle, although about 7,000 troops under Davout were still a long way south toward Vienna. The Allies numbered about 85,000 soldiers, seventy percent of them Russian, and 318 guns. The French army was outnumbered and Napoleon was initially uncertain of his victory. In a letter to Foreign Minister Talleyrand, Napoleon asked him not to tell anyone about the upcoming battle, as he did not want to upset Empress Josephine. According to Frederick C. Schneid, Napoleon's main concern was not Josephine's peace of mind, but how to explain to her a defeat by the French army.

The Battlefield

The battle took place about ten kilometers southeast of the city of Brno, between that city and Austerlitz (Czech: Slavkov u Brna) in what is now the Czech Republic. The northern part of the battlefield was dominated by the 210 m Santon Hill and the 260 m Žuráň Hill, both overlooking the vital Olomouc/Brno road in an east-west direction. To the west of the two hills was the village of Bellowitz (Bedřichovice), and between them the Bosenitz (Roketnice) stream that ran south to connect with the Goldbach (Ricka) stream, which flows between the villages of Kobelnitz (Kobylnice), Sokolnitz (Sokolnice) and Telnitz (Telnice). The center of the entire area was the Pratzen Heights (Pracký kopec), a gently sloping hill about eleven or forty feet high. An adviser claimed that Napoleon repeatedly told his marshals: 'Gentlemen, examine this ground carefully, it will be a battlefield; you will play a role in it."

Plans and dispositions of the allies

An allied council met on December 1 to discuss proposals for battle. Most Allied strategists had two fundamental ideas in mind: contact the enemy and secure the southern flank that maintained the line of communication to Vienna. Although the tsar and his immediate entourage pressed for a battle, the Emperor Franz of Austria was more cautious and, as mentioned, was seconded by Kutuzov, the commander-in-chief of the allied troops. However, the pressure to fight from the Russian nobles and Austrian commanders was very strong, so the Allies adopted the plan of Austrian chief of staff Franz von Weyrother. He planned a main attack on the French right flank, which the Allies thought was weaker, and attacks diversion against his left flank. The allies deployed most of their troops in four columns that would attack the French right. The Russian Imperial Guard remained in reserve while Russian troops under the command of Pyotr Bagration protected the Allied right flank. On the other hand, Tsar Alexander abruptly withdrew authority from him to the commander-in-chief Kutuzov and gave it to Franz von Weyrother. In the battle Kutuzov was only able to command the IV Corps of the allied army, despite the fact that he was still the de jure general because the tsar was afraid of taking responsibility in case his plan failed..

Plans and provisions of the French

Napoleon hoped that the Allied forces would attack, and to force them to do so, he deliberately weakened his own right flank. On 28 November Napoleon met his marshals at Imperial Headquarters and they informed him of their doubts about the impending battle. They even suggested a withdrawal, but the emperor brushed off his complaints.

Napoleon's plan called for the Allies to throw in large numbers of troops to envelop his right flank in order to cut the French line of communication with Vienna. As a result, the Allies' central and right flanks would be more exposed and more vulnerable. In order for them to do so, Napoleon even abandoned the strategic position of the Pratzen Heights, feigning weakness and nervousness. Meanwhile, Napoleon's main force would hide in front of the Heights and, according to the plan, he would attack and recapture the ridge, then launch a decisive attack into the center of the Allied line, paralyzing it and surrounding it from the rear.

If the Russian force leaves the High Pratzen to go to the right flank, it will certainly be defeated.Napoleon

The massive push through the Allied center was led by the 16,000 men of Marshal Soult's IV Corps. The position of this corps was shrouded in dense fog during the opening stages of the battle; in fact, the length of time that fog lasted was vital to Napoleon's plan. Soult's troops would be discovered if the fog lifted too soon, but if it lingered too long, Napoleon would not be able to tell if the allies had left the Pratzen Heights and would prevent him from launching his well-timed attack.

Meanwhile, to support his weak right flank, Napoleon ordered Davout's III Corps to march from Vienna to join General Legrand's men, who held the far southern flank as it was to bear the brunt of the attack ally. Davout's soldiers had 48 hours to cover 110 km. His arrival was crucial to the success of the French plan, since Napoleon's position on his right flank was very risky due to the weakness of the troops garrisoned there. However, the reason Napoleon was able to use a risky plan was because Davout, commander of III Corps, was one of his best marshals, because his right flank position was protected by a complicated system of streams and lakes, and because the French had already established themselves in a secondary line of retreat through Brunn (Brno). The Imperial Guard and Bernadotte's I Corps were held in reserve while the V Corps under Jean Lannes held the northern sector of the camp. battlefield, where the new line of communication was located.

By December 1, French troops had moved in accordance with the movement of the Allies to the south, just as Napoleon expected.

Start of the fighting

The combat actions began around eight in the morning on December 2, 1805, when the first allied column attacked the town of Telnitz, defended by the 3rd.er Line Regiment. This sector of the battlefield was the scene of much fighting in the aftermath with various Allied charges driving the French out of the town and forcing them back to the other bank of the Goldbach stream. The first men of Davout's corps arrived at this moment and drove Telnitz's allies out, but were then attacked by hussars and again driven from the town. Further Allied attacks on Telnitz were stopped by French artillery.

The Allied columns began to charge into the French right, but not at the desired speed as the French successfully held them back. In reality, the Allied attacks were misguided and untimely: the Liechtenstein cavalry detachments on the Allied left flank had to be placed on the right and, in the move, encountered and delayed part of the 2nd Allied column. infantry advancing against the French right. The planners at the time thought it a disaster, but it would later prove helpful. Meanwhile, the vanguard of the second column was attacking the village of Sokolnitz, defended by the 26th Light Regiment and tirailleurs, French skirmishers. Initial Allied assaults were unsuccessful and General Langeron ordered the bombardment of the village, driving the French out. At the time the third column attacked the castle of Sokolnitz. The French counterattacked and retook the town only to be driven out again. Fighting in the sector temporarily ceased when Louis Friant's division, part of III Corps, took over the town. Sokolnitz was perhaps the most hotly contested on the battlefield and changed hands several times throughout the day.

As Allied troops attacked the French right flank, Kutuzov's IV Corps halted at the Pratzen Heights and stayed there. Like Napoleon, Kutuzov realized the importance of Pratzen and decided to protect the position, but the tsar misunderstood and drove the IV Corps off the Heights, pushing the allied army into his grave.

“One strong blow and the war is over”

About 8:45 a.m., satisfied by the weakness of the enemy center, Napoleon asked Soult how long it would take his men to reach the Pratzen Heights, to which the marshal replied: "Less than twenty minutes, sire ». About a quarter of an hour later the French Emperor ordered the attack, adding: "One strong blow and the war is over".

Dense fog helped cover the advance of Saint-Hilaire's division, but as they ascended, the legendary "Sun of Austerlitz" dissipated the mist and gave them courage. The Russian soldiers and officers who were at the top they were surprised to see the number of enemy soldiers advancing towards them. After an hour of fighting, the Allied 4th Column was almost completely destroyed, although other soldiers from the 2nd, mostly inexperienced Austrians, also participated. and they matched forces in the fray against one of the best fighting forces in the French army, which they momentarily drove from the halt. However, in despair, Saint-Hilaire's men again charged the bayonet and gained the position. To the north, General Vandamme's division attacked in an area called Staré Vinohrady ("Old Vineyards") and thanks to their skilled tirailleurs and deadly rifle volleys they wiped out several enemy battalions.

The battle had clearly turned in favor of the French side, but it was far from over. Napoleon ordered Bernadotte's I Corps to support Vandamme's left and moved his own command center from Zuran Hill to St Anthony's Chapel on the Pratzen Heights. The plight of the Allies was confirmed by their decision to send the Russian Imperial Guard, under the command of Grand Duke Constantine, Tsar Alexander's brother, to counter-attack in the Vandamme section of the field, forcing bloody fighting and the only loss of one French unit in battle, a battalion of the 4th Line Regiment. Anticipating trouble, Napoleon ordered his heavy cavalry guard forward, which annihilated their Russian counterparts but failed to settle the battle due to the large number of mounted units on both sides involved in the fight. The Russians had a numerical advantage, but the intervention of the Drouet division, second of Bernadotte's I Corps, allowed the French cavalry to seek refuge behind their lines. The horse artillery of Napoleon's guard also inflicted heavy casualties on the Russian cavalry and riflemen, who aborted the action and fell in great numbers while pursued for almost half a kilometer by the strengthened Gallic cavalry. Russian casualties at Pratzen included Kutuzov, seriously wounded, and his stepson Ferdinand von Tiesenhausen, killed in action.

Ending

I was... under a ferocious and continuous artillery fire... Many soldiers, immersed in intense fighting from 7 a.m. to 4 p.m., were left unarmed. I couldn't do anything but withdraw...General Lieutenant Przhebishevsky

Meanwhile, the northern part of the battlefield was also witnessing heavy fighting. The Prince of Liechtenstein's heavy cavalry began to assault Kellerman's French light cavalry forces having reached their correct position in the field. The fighting began in favor of the French, but Kellerman's troops took cover behind General Caffarelli's infantry division once it became clear that the number of Russians was too large. Caffarelli's men stopped the Russian assaults and allowed Joachim Murat to send two cuirassier divisions into the fight, commanded by d'Hautpoul and Nansouty, to put an end to the tsarist cavalry. The skirmish was fierce and long, but the French prevailed. Then Lannes launched his V Corps against Piotr Bagration's troops and, after hard fighting, managed to expel the expert Russian commander from the battlefield. Lannes wanted to pursue him, but Murat, in charge of that sector, was against the idea.

Napoleon's attention then shifted to the southern end of the battlefield, where his troops and allies continued to fight for Sokolnitz and Telnitz. In a double attack, St. Hilaire's division and part of Davout's III Corps attacked the enemy at Sokolnitz and persuaded the commanders of the two columns, Generals Kienmayer and Langeron, to flee quickly. Buxhowden, the Russian commander of the Allied left wing and the man responsible for leading the attack, was completely drunk and also fled. Kienmayer covered his retreat with O'Reilly's light cavalry, who also gallantly defeated five of the six French cavalry regiments before having to withdraw as well.

Then a general panic seized the allied army and they began to leave the battlefield in all possible directions. During this retreat a famous and terrible episode occurred: the Russian forces defeated by the Gauls were retreating south towards Vienna across the frozen Satschan Ponds. French artillery attacked them and broke through the ice, causing many men to drown in the icy waters and dozens of artillery pieces to sink. Source estimates of how many guns were captured in this action differ, ranging from 38 to over 100, as well as the number of casualties, which ranged from 200 to over 2,000. Because Napoleon exaggerated this incident in his report on the battle and since the tsar tacitly accepted it as an excuse for such a catastrophic defeat, the more conservative figures must be closer to reality. Many drowned Russians were rescued by the French. However, local evidence, made public much later, suggests that Napoleon's account is entirely fictitious, as on the Emperor's instructions the lakes were drained a few days after the battle and only the bodies of two or three men and about 150 horses were found.

Consequences

Austerlitz and the previous campaign profoundly altered the nature of European politics. In three months the French had occupied Vienna, smashed two armies, and humiliated the Austrian Empire. These facts contrast with the rigid power structures of the 18th century. Austerlitz laid the foundation for almost a decade of French domination of the European continent, but another of the imminent effects of it was to provoke war with Prussia in 1806.

Military and Political Results

Allied casualties were around 27,000 in an army of 73,000 men, 37% of its strength. The French lost about 9,000 out of a force of 67,000, or 13%. The allies also lost 180 guns and 50 banners. The great victory was received with astonishment and delirium in Paris, since a few days before the nation was on the verge of a financial collapse. Napoleon wrote to Josephine: «I have defeated the Austro-Russian army commanded by two emperors. I'm a little tired... A hug." Perhaps the best summary of the hard times for the allies was made by Tsar Alexander: "We are babies in the hands of a giant."

France and Austria signed a truce on December 4 and signed the Treaty of Pressburg twenty-two days later. Austria agreed to recognize French territory captured by the treaties of Campo Formio (1797) and Lunéville (1801), cede land to Bavaria, Württemberg and Baden, who were Napoleon's German allies, pay forty million francs in war indemnities, and deliver Venice to the Kingdom of Italy. It was a harsh end for Austria, to be sure, but not a catastrophic peace. The Russian army was allowed to withdraw to its homeland and the French encamped in southern Germany. The Holy Roman Empire disappeared in 1806. Napoleon created the Confederation of the Rhine, made up of a series of German states on the border between France and Prussia. Prussia saw these moves as an affront to its status as the leading power in Central Europe and went to war against France in 1806.

Rewards

Napoleon's words to his troops after the battle were very complimentary: Soldats! Je suis content de vous (English: Soldiers! I am very proud of you.). The Emperor provided two million francs for the senior officers and two hundred francs for each soldier, as well as generous pensions for the widows of the fallen. The orphaned children were adopted by Napoleon personally and were allowed to add "Napoleon" to his baptismal and family names.The French emperor never granted noble titles to any of his generals, as was customary after a great victory. It is likely that he did not significantly elevate anyone because he regarded Austerlitz as a personal triumph.

Popular impact

War and Peace

The battle of Austerlitz is a pivotal event in Leo Tolstoy's novel War and Peace. About to start the battle, Prince Andrei Bolkonski, one of the main characters, thinks that the upcoming "day [will be] his Toulon, or his Arcole", references to Napoleon's latest victories. Andrei awaits glory, always thinking of him, “I will march forward and sweep everything I come across.” However, later in the battle, Andrei falls into the hands of the enemy and even meets his hero, Napoleon.. Tolstoy portrays Austerlitz as an early test of Russia, one that ended badly, because the soldiers fought for irrelevant things, like glory or fame, rather than the virtues that would enable, for example, victory at Borodino in the 1812 invasion..

Historical overview

Napoleon's victory over the allies was not as successful as he had hoped, but historians and aficionados acknowledge that the original plan brought him a significant victory. For that reason, Austerlitz is sometimes compared to other great tactical battles, such as Cannae or Höchstädt. Some historians suggest that Napoleon was so successful at Austerlitz that he lost touch with reality, and what used to be French foreign policy became Napoleon's own after the battle. In French history, Austerlitz is recognized as an impressive military victory, and in the 19th century, when fascination with the First Empire was at its height, the battle was revered by Victor Hugo that, "in the back of [his] thought", he was hearing the "sound of heavy cannons rolling towards Austerlitz". However, on the recent bicentenary controversy erupted when the then President and Prime Minister of France, Jacques Chirac and Dominique de Villepin, respectively, did not attend any commemoration of the battle. On the contrary, some citizens of the overseas departments of the French country protested against what they saw as the "official commemoration of Napoleon", arguing that Austerlitz should not be celebrated because they believed that Napoleon had committed genocide against the colonized peoples.

After the battle, Tsar Alexander I blamed everything on Kutuzov, commander-in-chief of the Allied army. However, it is clear that Kutuzov's plan was to fall back to the rear, where the Allied army had a logistical advantage.. In that case, the allies could have been reinforced by Archduke Charles's troops in Italy and the Prussians could have joined the coalition against Napoleon. A French army on the edge of its supply lines, in a place without supplies, could have met a very different end than it did at Austerlitz.

Contenido relacionado

27

Annex: Annual table of the fourteenth century

Aquatint engraving