Basque Country

Euskal Herria (traditionally, equivalent to Basque Country , and sometimes also interpreted as Basque Country ) is the name in Euskera of the European territory in which the Basque culture has developed. Located on both sides of the Pyrenees, it is usually divided into two parts called Iparralde (northern part), the French side, and Hegoalde (southern part), the Spanish side. Culturally and historically, its center or capital is set in Pamplona.

The term «Euskal Herria» appears in Basque writings for the first time in the 16th century, but it does not begin to be used in Spanish until the XIX, in the historical and political context of the rise of Basque nationalism. It has also been used historically by the Carlists. For all of the above, this denomination is controversial, also in the Basque Country. Currently, it is usually associated with Basque nationalism, and has come to generate institutional tensions between the autonomous communities of the Basque Country and Navarra. The first reference to Euskal Herria appears in a manuscript in Basque by Juan Pérez de Lazarraga from Alava, dated between 1564 and 1567, written as eusquel erria and eusquel erriau. It also appears in the Basque translation of the New Testament by Joanes Leizarraga, published in 1571, as heuscal herria or Heuscal-Herrian.

The historical region is usually divided into seven provinces, regions or countries: in Spain, Álava, Vizcaya and Guipúzcoa, which make up the Basque Autonomous Community, as well as Navarra; in France, Lower Navarre, Labort and Sola, which make up the French Basque Country.

The different currents of Basque nationalism derive their political projects around the Basque Country, going beyond the cultural sphere, which is why these projects are highly controversial. Some authors, limiting themselves solely to the anthropological or cultural conception of Euskal Herria, they prefer the Castilian and older forms of "Vasconia" or simply "País Vasco".

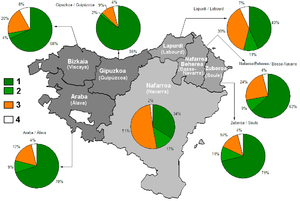

| Map of Euskal Herria |

|---|

Spanish euskera |

| Territories covered by Euskal Herria, according to the official administrative division, in Spanish, Basque and French |

About the term

For centuries there has been widespread use of the name Euskal Herria to designate a territory with well-defined cultural traits, above political-administrative borders and above historical differences. This academic institution, completely alien to the political terrain and above all creed and ideology, and responding to one of the purposes set out in Royal Decree 573/1976 of 26 February, which recognizes Euskaltzaindia – Royal Academy of the Basque Language, namely, the purpose of guardianship of the language, cannot fail to reiterate the property and suitability of the denomination Euskal Herria, a name that belongs to all. All this without prejudice, of course, of the names of each of the territories or of the political-administrative denominations. For all the above, this Royal Academy reiterates the ownership, correction and suitability of the name Euskal Herria for the whole of the seven provinces or territories, name not assimilable or equivalent to any of the political-administrative realities. At the same time, it recalls the need to respect a secular tradition that nothing and no one can interrupt or misrepresent. - Report of the Royal Academy of Basque Language/Euskaltzaindia on the name Euskal Herria

|

The term euskal translates as «relative to the Basque language», and herri(a) has the meaning of «town, locality, population, territory, country, homeland..." so Euskal Herria can be translated as "the land of the Basques", "the Basque country", "the Basque people" or "country of the Basques". In the 1979 Statute of Autonomy, the Statute of Guernica, it appears used in the second way, although the first is more common together with the third, especially in encyclopedic and documentary content. It should be noted that in the Basque media in Spanish there is a tendency not to translate the term or to use the word Vasconia in favor of Euskal Herria.[citation required]

It should be noted that the territory covered by Basque, a language prior to the incorporation of Indo-European languages around the year 4000 B.C. C., has fluctuated a lot throughout history, as has happened in the rest of the languages. For example, Euskera was spoken in La Rioja, north of Soria, northeast of Burgos, Huesca Pyrenean valleys, but in turn it receded in Renaissance times from Las Encartaciones and from most of the left bank of the mouth of the Nervión, reaching almost disappear in this area with industrialization (late 19th century and XX) according to Xabier Kintana and Julio Caro Baroja. In the Lower Ribera de Navarra it disappeared between the 1st and 10th centuries. It was also possible to speak in the Aran Valley for what is believed to have been spoken from the Bay of Biscay to the Mediterranean. There are also many hypotheses about its extension in prehistoric times, none of them sufficiently proven.[citation required]

Due to the cultural and educational movement of the ikastolas and the implementation of educational models that favor learning in Basque, it is recovering, especially on the left bank of the Nervión and around Tudela (Ribera de Navarra). Another factor that helps to recover the Basque language is the generalization of the attention to the public in that language, for the sake of the normalization of its use, in the organizations that depend on the Basque public administrations and in part of the Navarrese. In many Of them, in their contests-oppositions knowledge of the language has a certain value and it is even necessary to demonstrate a certain level to fill some positions requiring a certain Certificate of linguistic profile, which has not been without some controversy.

The term Vasconia or Wasconia has been used to refer to some part of what is now understood as Euskal Herria. The Duchy of Vasconia, constituted on the territorial basis of the circumscription or ducatus of the Roman province of Novempopulania and which extended from the south of the lower course of the Garonne River to the continental slope of the Pyrenees, ago reference to the historical affinity of the inhabitants of those lands with those on the other side of the Pyrenees. The Basque provinces, Álava, Guipúzcoa and Vizcaya are currently officially called the Basque Country or "Euskadi" (Euzkadi), a neologism constructed by Sabino Arana to refer to Euskal Herria, a term that he considered typical of the Carlists.

During the XX century, the Carlists continued to use the name of "Euskalerría" as opposed to that of "Euskadi". Thus, in a rally held in 1934 by the Traditionalist Communion in Algorta, they affirmed:

in front of the Basque separatist the Spanish Euskalerria.

The voice "Vasconia" it has fallen into disuse in favor of Euskal Herria, with more anthropological than geographical connotations, although until the unification of the Basque language it was also called Euskalerria, Euskalerría, Eskualerria or Eskualerría.

Currently, perhaps due to the influence of the Statute of Guernica, the Basque Country and Euskadi are understood as synonyms (the term Basque Autonomous Community is also used), while Euskal Herria maintains the meaning previously given to the term Euskadi, that is to say; the seven traditional territories.

Retrospective on the use of the voice

The term Euskal Herria appears for the first time written in the Alava dialect in the Lazarraga manuscript (1564). It appears on three different occasions and on all of them in the form of Hegoalde, that is, without the H, lost according to Mitxelena around the XIII century and as euskal (or in this case euskel) and not eskual or uskal (as in the case of Iparralde).

beti çagie laudatu

çegaiti doçun eusquel erria

aynbat bentajaz dotadu. (f. 18)çegayti eusquel erian dira

ederr guztioc dotadu. (f. 18v)çeñetan ditut eçautu

eusquel erriau ow, nola eben

erregue batec pobladu. (f. 18v)You will always be praisedbecause you have endowed Euskal Herria

of so many advantages.why it has been endowed

a Euskal Herria of all these beauties.in which I have met

a king has populated it.

like this Euskal Herria

Miretsico duçue, aguian, nic, Euscal-Herrico ez-naicelaric, euscaraz esquiribatceco ausartciaren hartcea.

iduritcen çait hoben nuqueiela, eta are eçagutça gutitaco eta esquer-gabe içanen nincela, baldin Euscal-Herrian iKhassia Euscal-Herrico probetchutan emplegatu ez-panu.

[...] ba-daquit Euscal-Herrian anhitz mouldz minçatcen direla, eta nori bere herrico euscara çaicala hoberenic eta ederrenic.

Ordea ea Saraco euscara denz Euscal-Herrico hoberena eta garbiena, ez-naiz or hartara sartcen, bat-bederac emanen du bere iduriric.

You may be amazed that I, without being a native of Euskal Herria, dared to write in Basque.[...] it seems to me that I would have done wrong, and would have been unsmart and ungrateful, if I hadn't used for Euskal Herria what I have learned in Euskal Herria.

[...] I know that in Euskal Herria they speak in very different ways, and that everyone considers that the Basque of his people is the best and most beautiful [...]

Instead, if Sara's euskera is or not the best and purest of Euskal Herria, I don't come in there, everyone will have his opinion.Esteve Materra, Doctrine Christiana (1617)

Badaquit halaber ecin heda naitequeyela euscarazco minçatce mold guztietara. Ceren anhitz mouldz eta differentqui minçatcen baitira euscal herrian, Naffarroa garayan, Naffarroa beherean, Çuberoan, Lappurdin, Bizcayan, Guipuzcoan, Alaba-herrian [...]I also know that I cannot reach all the ways of talking about euskara. For it is spoken in many ways and differently in Euskal Herria, in the Alta Navarra, in the Baja Navarra, in Zuberoa, in Lapurdi, in Bizkaia, in Gipuzkoa, in the land of Álava [...]Pedro de Axular, Gero (1643)

Joanes Leizarraga, a Protestant priest from Labour, who died around the year 1605, author of the Basque translation of the New Testament, published in 1571, testifies to this general use of Euskal Herria. modality understandable by all readers, write

[...] batbederac daqui heuscal herrian quasi etche batetic bercera-ere minçatzeco manerán cer differentiá eta diuersitatea den[...] anyone knows what difference and diversity there is in the way of speaking in Euskal Herria almost from one house to another.

This passage is in the prologue to the Basques (“Heuscalduney”), after the bilingual letter (Basque / French) that the author addresses to Queen Juana of Navarre. The same name is used again by the same author in the same year but this time separated by a hyphen in his ABC edo christinoen instructionea:

Heuscal-herrian gaztetassunaren racasteco carguä dutenér eta goitico guciér. Leiçarraga Berascoizcoac Iaincoaren gratia desiratzen”.

Eta minçatzeco formaz den beçembatean, Heuscal-herrian religionen exercitioa den lekuco gendetara consideratione guehiago vkan dut, ecen ez bercetara

Legally today

Euskal Herria (equated with Basque town) legally and in accordance with the Statute of Guernica in Basque is constituted as an autonomous community, which may well receive the name in Basque of Euskal Herriko Komunitate Autonomoa or Euskadi.

In Spanish this term is translated in two different ways:

“Basque People”:

1. artikulua.

'Euskal Herria', bere Naziotasunaren adierazgarri, eta bere burujabetasuna iristeko, espainol Estatuaren barruan Komunitate Autónomo gisa eratzen da. Beronen izena Euskadi zein Euskal Herria izango da; eta Konstituzio eta Statute honetan adierazten direnak izango ditu oinarrizko instituzio-arautzat.Article 1.

The Basque people or Euskal Herria, as an expression of its nationality, and to access its self-government, is constituted in Autonomous Community within the Spanish State under the denomination of Euskadi or Basque Countryin accordance with the Constitution and the present Statute, which is its basic institutional rule.Statute of Autonomy of the Basque Country of 1979

“Basque Country”:

2. artikulua.

1.- Araba, Bizkaia eta Gipuzkoak, Nafarroak bezala, Euskal Herriko Komunitate Autonomoaren partaide izateko eskubidea dute.Article 2.

1.- Álava, Guipúzcoa and Vizcaya, as well as Navarra, have the right to form part of the Autonomous Community of the Basque Country.Statute of Autonomy of the Basque Country of 1979

In the political arena

Political use of the term

The concept of Euskal Herria originally had an exclusively cultural dimension, since it deals with the way in which Basque-speakers from the 20th century XVI have historically called the territories in which their language was spoken (or the territories in which, even without Basque being spoken, they belonged to territories with a great Basque-speaking imprint, in the case of Ribera de Navarre).

With the emergence of Basque independence nationalism from the end of the XIX century, Sabino Arana created the name Euzkadi to differentiate themselves from the fueristas politically represented by the "Euskalerriacos" led by Fidel de Sagarmínaga and Ramón de la Sota (later he would join the PNV), who socially sought to appropriate the term Euskal Herria, although he habitually used the term Euskeria in his articles. > (for example: "This nationalist party was only born and lives for the Homeland, which is free Bizkaya in free Euskeria").

The carlist, fundamentalist and euskalerriaco parties are Spanishists, and therefore enemies of Bizkaya.

In fact, cheers to Euskal Herria are launched in the original lyrics of the Oriamendi march, still today a Carlist anthem, which later —with different lyrics— would be one of the combat hymns of the Requeté and, by decree of February 27, 1937 approved by General Franco, national song of National Spain along with the Cara al sol of the Falange and the Marcha Real.

Subsequently, some nationalist ideologues such as Arturo Campión defended the voice Euskal Herria considering it more historic and understandable than the recently created Euzkadi, defended by the most purist aranistas such as the José Agerre from Navarra, and also capable of maintaining the same political significance as the latter.

During the Franco dictatorship, nationalist ideas were severely repressed, but the term Euskal Herria was allowed, as it was the term that the Carlists had been using since even before the birth of Basque nationalism.[citation required] Proof of this is the distinction made in 1973 by a censor, citing Unamuno, between Euzkadi and Euskal Herria:

In the opinion of the reader who subscribes, it is necessary to encourage, stimulate and help all those works in which the old and glorious word Euskal Erria appears, still used by the authentic and noble Basques. It's a criterion that doesn't fail.NOTE: The difference between saying "Gora Euzkadi" and "Gora Euskal Herria" is as follows: "Gora Euskal Herria": Viva Spain and Vasconia

«Gora Euzkadi»: Viva Euzkadi and outside SpainJoan Mari Torrealdai: The Censorship of Franco and the Basque theme, p. 89

Or that the ultra-right party Fuerza Nueva admit Euskal Herria instead of Euskadi.

The political use of the term Euskal Herria by a part of Basque nationalism is, in any case, very recent (since the 1990s), today the expression Euskal Herria is widespread throughout nationalist political parties, although some sectors (mainly from the PNV) prefer the use of the neologism Euzkadi or Euskadi, even though the creation and development of the autonomous community of the Basque Country, as a result of the Guernica Statute, has led to the identification of this with Euskadi. In any case, this neologism is gradually being displaced by the older term.

The Guernica Statute of 1979 states:

The Basque or Euskal Herria, as an expression of its nationality, and to access its self-government, is constituted in Autonomous Community within Spain under the name of Euskadi or Basque Country, in accordance with the Constitution and the present Statute, which is its basic institutional norm.

This Statute politically identifies the autonomous community of the Basque Country, Euskadi, the Basque Country, the Basque People and Euskal Herria, considering that all these terms are equivalent. This wording led the Royal Academy of the Basque Language (Euskaltzaindia) to draw up the Report of the Royal Academy of the Basque Language/Euskaltzaindia on the name Euskal Herria.

Featured personalities, such as the essayist José Miguel de Azaola and many others, openly showed their disagreement over the text of this Article and the pretense –velada o no – of eliminating the name Euskal Herria.[...]This academic institution, completely alien to the political terrain and above all creed and ideology, and responding to one of the purposes set out in Royal Decree 573/1976 of 26 February, by Eultdia In order to protect the language, it cannot fail to reiterate the ownership and suitability of the name Euskal Herria, a name that belongs to all and that in no way must be taken in a partisan sense, as unfortunately has happened and happens. All this without prejudice, of course, of the names of each of the territories or of the political-administrative denominations.

In 2009, the Minister of Education of the Basque Country Isabel Celaá (Socialist Party of Euskadi-Euskadiko Ezkerra) when asked about the use of the term in the Basque curriculum confirmed that it would continue to be present:

for the simple reason that Euskal Herria exists, is the country of the Basque Country and is a territory of culture and common language that we share the Basques [...] a territory where other seven different are conjugated (Euskadi, Navarra and the three Basque provinces) and therefore will appear again and again in the Basque curriculum [...]

Although he indicated that the Ministry was going to:

specify exactly what is Euskal Herria because children have the right to receive an education that is scientific, founded in reality

denying that Euskal Herria was a legal-administrative reality:

a legal-administrative entity, as appears in the curriculum prologue that we are trying to improve

Days later, Iñaki Oyarzabal (Partido Popular) also defended the use of the term Euskal Herria to define the Basque cultural reality, alleging that:

Euskal Herria responds to a cultural reality, a linguistic landscape.

Pretension of political-administrative union

The territory currently defined as Euskal Herria had its first political complicity and unity between the 5th and 8th centuries (it was the union of the majority of the Basque tribes as one) as a response to the continuous incursions and attacks of the Germanic peoples after the fall of the Roman Empire. During the reign of Sancho Garcés III the Greater (1004-1035), the kingdom of Nájera-Pamplona (see map), ancestor of the Kingdom of Navarre, reigning for the last six years (1029-1035) over almost the entire Christian north of the peninsula, reigned over most of the Basque territories. Some authors defend that it included among its domains those corresponding to the French Basque Country, without however including the Ribera Baja, which would not be conquered from the Muslims until the following century. For this reason they consider the reign of Sancho III as the only stage in which the Basque people were united under the same political reality. Other authors, such as Armando Besga, think otherwise.

Today various sectors (especially Basque nationalists) defend the political union of the seven historical and traditional Basque territories in a common political-administrative entity.

There are different political projects on Euskal Herria facing this common entity, some defend the creation of its own state and independent from Spain and France (maximum objective of Basque nationalism), while others defend a territorial collaboration between the current institutions existing in said territory. Today no union proposal is put into practice.[citation required]

Interpretation of the Basque Country as a nation

The concept of Euskal Herria as a nation is controversial. In addition, some nationalists prefer to use the expression Euzkadi to refer to the Basque nation.

Basque nationalists consider that their homeland must be sovereign to be able to determine itself and decide their political status, and for many of those who feel part of that community, their capital would be Pamplona.

The "national" Basque has a very different degree of support in each of the territories. A study by "Fórum Radio Euskadi" shows that in the Basque Country 52% of those interviewed consider it a nation while this belief is supported by 32% in Navarra and 34 % in the French Basque Country.

According to data from the Euskobarómetro of June 2019, 46% of Basques claim to have a nationalist sentiment compared to 50% who do not. 38% of Basques consider themselves as Basque as Spanish, 26% only Basque, 25% more Basque than Spanish, 4% only Spanish and 3% more Spanish than Basque.

According to data from the Navarrometer in 2001, 18% of Navarrese considered themselves only Navarrese and 21% Navarrese and Basque, while 44% considered themselves Navarrese and Spanish and 6% Navarrese, Basque and Spanish. The same study in 2016 indicates that 45.1% consider themselves only Navarrese, 20.1% Basque and Navarrese, 8.9% Spanish, 8.6% Basque, Navarrese and Spanish, 6.8% Navarrese and Spanish, 5.4% only Basque and 5.1% European. The Navarrese identity would reach 80.6%, the Basque identity 34.1%, the Spanish identity 24.3% and 66.7% consider themselves a European citizen in one way or another.

In the French Basque Country, according to a study carried out by the Basque Studies Society, 36% of the inhabitants consider themselves only French, 45% Basque and French at the same time (to a greater or lesser extent, both more Basque than French as more French than Basque) and 11% consider themselves exclusively Basque.

Given the prospect of a hypothetical independence referendum in the Basque Country, 31% of citizens would vote yes, 48% no, and 21% would not vote or would not vote.

A CIS survey made public in 2012 shows that 42.6% of Basques would be against independence compared to 41.5% who would be in favor, while 15% do not know or do not answers. This study also shows that 36.9% of those surveyed feel Basque and Spanish compared to 25.2% who feel exclusively Basque and 5.9% only Spanish. Based on the electoral results of the different political parties in these territories, it can be inferred, with due caution, that the feeling of belonging exclusively to a Basque nation could only be in the majority in Vizcaya and Guipúzcoa (which add up to more than 60% of the total population of Euskal Herria and whose territory is somewhat greater than 20% of the total).

Basque feeling is varied in Euskal Herria, both in the way it is interpreted and in its presence by territory. The feeling of Basque identity in Navarre is the most politically diverse and controversial. In a 1994 survey, the Navarrómetro said that 38% of Navarrese considered themselves very or quite Basque, while 12% considered themselves somewhat Basque and 50% considered themselves little or not Basque at all, and according to a study carried out by Radio Euskadi Forum 41.7% of Navarrese consider Navarra part of Euskal Herria while 49.5% do not.

Geography

The territory covers an area of 20,664 km². It is located in the western vertex of the Pyrenees and its coastline is bathed by the Cantabrian Sea. It has a population of approximately 3,000,000 people, of which around 2,600,000 have Spanish citizenship and the rest French. Euskal Herria is made up of seven territories, sometimes referred to by the Basque term lurralde or herrialde:

- Vizcaya

- Guipuzcoa

- Álava

- Navarra

- Baja Navarra

- Labort

- Sola

There are two territories that Basque nationalism considers to be parts of Euskal Herria but that administratively do not currently belong to any of the aforementioned territories; It is the Enclave of Treviño, which administratively belongs to the province of Burgos (Castilla y León) and the municipality of Valle de Villaverde, which belongs to Cantabria.[citation required]

Main cities

Metropolitan areas

- Gran Bilbao: 868 745 inhabitants

- San Sebastian region: 444 152 inhabitants

- Pamplona metropolitan area: 346 716 inhabitants

- Functional area of Vitoria – Central Álava: 280 948 inhabitants

- Éibar-Durango metropolitan area: 126,190 inhabitants[chuckles]required]

- Bayona-Anglet-Biarritz: 126 072 inhabitants[chuckles]required]

Extensions and geographic data

Source Datutalaia

Mountain systems

The territory in which the Basque people settle is especially mountainous. Most of its mountain ranges are located on the west-east axis. The most common rock is calcareous, but also granite.

The highest peaks are in the Pyrenees, with the Mesa de los Tres Reyes being the highest peak. This mountain range is born next to the sea, ascends from west to east and the first peak that exceeds 2000 meters is the Orhi, of great mythological importance.

To the south of Navarra and Álava is the range of the Sierra de Toloño, the Sierra de Cantabria and the Sierra de Codés.

Between these two main mountain ranges are the Basque Mountains. They are oriented from east to west and are made up of mountains such as Gorbea, Urbasa, Andia, Amboto, Ordunate or Aizkorri.

History of the territories of Euskal Herria

The term Euskal Herria encompasses different territories and political realities, only culture and language are the common element to all of them with the differences that are normal among the various populations. The vision of the concept of these aspects, culture and history, should not be taken as if Euskal Herria were an existing political entity, beyond what was stated above, since this would lead to a biased vision.

The language has undergone a progressive process of loss of territoriality, exacerbated after the 40 years of Franco's dictatorship, and has been shrinking around the Bay of Biscay and the Pyrenees. Many of the territories where Basque was spoken are outside what is understood by Euskal Herria and in many of the territories that make it up the use is minority.

History has gone through very different stages in which these territories have been under different powers, some centered on cities that remain in what is known as Euskal Herria, such as Pamplona, and others in centers far from them.

This includes a series of common historical and cultural data typical of the different current political realities (beginning of the XXI century). Each of these realities has its own particularities in its own article.

Origins

Various hypotheses point out that already in prehistoric times the Basques, or different tribes that spoke languages very similar and related to the current Basque, already inhabited the lands that today make up Euskal Herria.

Paleogenetic investigations (studies based on mitochondrial DNA) carried out by Peter Forster assume that all of Europe was colonized by the inhabitants of Iberia after the last ice age.

The studies by Alzualde A, Izagirre N, Alonso S, Alonso A, de la Rúa C. based on the mitochondrial DNA of human remains from the prehistoric cemetery of Aldaieta (Álava), confirm that there is no difference between these burials and the rest of the Atlantic Europeans.

Studies carried out by René Herrera, from the University of Florida, as well as by three anthropologists from the UPV-EHU, Mikel Iriondo, María del Carmen Barbero and Carmen Manzano, find differences between the inhabitants who currently inhabit the different Basque territories. Some even point to different types among the Basques

An article published in January 2003 in Investigación y Ciencia, the Spanish edition of the magazine "Scientific American", reviewed a study by two German scientists (Elisabeth Hamell and Theo Vennemann) who were investigating the origin of common Basque and pre-Indo-European of almost all of Europe, based on linguistic aspects. Venneman states that:

We do not fall into exaggeration if we claim that Europeans are all Basque.

But Venneman's proposal has been highly criticized by Basque scientists and is not accepted by many specialists in linguistics.

At the beginning of the 19th century, the writer and scholar Juan Antonio Moguel exposed in his book "History and geography of Spain illustrated from the Basque language" (study of the etymology of the place names of the Iberian Peninsula carried out from the Basque language) that the ancient inhabitants of Iberia spoke languages of the same family to which current Basque belongs, coinciding with their contemporary the German scientist Wilhelm von Humboldt, defender of Basque-Iberianism, that is, that the Basque language is a direct descendant of the Iberian language.

The hypothesis of late Basqueization maintains that current Basques come from Aquitaine.[citation required]

Rome

According to the Roman historians Plinio, Mela, Floro or Silio Itálico, the territories of present-day Euskal Herria were inhabited by several tribes whose language and affiliation are unknown.

Roman politicians and historians differentiated the Vascones from the Varduli, Caristians and Autrigonians. The Basques occupied part of Navarre and Aragon, and were administratively dependent on the Caesar Augustan convent, whose capital was present-day Zaragoza. The Várdulos, Caristios and Autrigones lived in what we know today as Guipúzcoa, Vizcaya and Álava (respectively) and their administrative unit was the Cluniense convent, whose headquarters were in Clunia, in the province of Burgos. Although there are various theories that consider that the Basques spread throughout the Basque territories (hence the term) and that for this reason Basque is spoken and mixed with the Celts who were fleeing from Roman pressure in the Ebro, creating the Basque dialects.

The Roman geographer Strabo cites the Vascones as the limit of the Celtic peoples of northern Spain. Gaius Julius Caesar, in his book "De Bello Gallico", explains that the Garona River divided the Gauls from the Aquitanians. Many Aquitanian inscriptions from the first centuries AD include words that seem to be Old Basque: ILVURBERRIXO, ANDEREXO, ASTOILVN, SEMBETTEN, BIHOSCIN, SENNICO, HARBELEX, CISON, CISSON, HARSORI, HERAVS, VM·ME·SA·HAR.

Romanization was strong in some of these lands, especially in the south of Navarra. There are testimonies of this Romanization in important cities and remains of important iron mines or other industries. Pamplona and Bayona, for example, were settlements founded by the Romans.

The fall of the Roman Empire gave way to the settlements and subsequent kingdoms of the Visigoths and Franks and the establishment by the Franks of the Duchy of Vasconia in France.

Some historians believe that the Visigoths did not come to dominate the Basques.

After Roman times, the following maps assume the existence of Vasconia, Gasconia or Basque lands around AD 500. C. (see map) and 600 d. C. (see map) and between 526-600 d. C. (see map).

Roncesvalles

In the year 778 the Battle of Roncesvalles took place where the Basques (some theories maintain that they were Muslims, who supported their relatives from Pamplona) defeated the rearguard of Charlemagne's army. He crossed the Pyrenees to support the Muslim governor of Zaragoza, Sulaiman ibn Yazqan ibn Al-Arabi against the central power of Al-Andalus [11] and on his way he appointed delegates in Pamplona, which at that time would be populated by Pamploneses, who were free and independent according to J. Arbeloa (Origins of the Kingdom of Navarra. San Sebastián, 1969). Once the Frankish (French) armies had gathered in the city of Zaragoza, the governor decided not to respect the signed pact and not hand over the city, so Charlemagne ordered its siege. The rebellion of the Saxon states, led by Wittekind, disrupts the plans of Charlemagne who raises the siege. On his return to Pamplona, he found that the city had rejected his delegates, so he destroyed the walls and headed for Roncesvalles on August 15, 778.

In that battle the Franks were defeated by the angry Navarrese, but the French created the epic legend, in which Roland (Roldán), prefect of the March of Brittany, blew his marvelous ivory olifant to warn the rest of the attacking army, and when he and the twelve imperial champions were wounded, he threw his glorious sword "Durandal" so that he would not fall into the hands of the enemy. The copy of the Song of Roland (the “Chanson de Roland”) preserved in the so-called “Oxford Manuscript”, made up of 4,002 verses grouped into stanzas, describes the Carolingian departure for Aquitanian lands and the disaster suffered by the rearguard commanded by Count Roldán, which would make him a hero of the songs of deed. In addition to him, Eggihard, butler of the royal table, and Anshelm, count palatine, died in combat, among many others.[12]

In modern Basque, the word "erraldoi" ("giant") seems to come from a medieval variation of the term that in Spanish has taken the form of "Roldán".

Navarre on the rise

In the second half of the 9th century and the 10th century (see map 900 AD) the Kingdom of Pamplona was established (see map 1000 AD), its first historical king being Íñigo Arista (Eneko Aritza), which obtained the support of most of the families in the territory under its rule, as well as that of the Muslim Banu Qasi of the Ebro valley.

From the 11th to the 16th centuries, the Kingdom of Navarre became Christianized and literate using the Romance style, which displaced Basque (Basque), Hebrew and Arabic as the commercial language (Ordinance of Huesca in 1349). The Lingua Navarrorum (Basque) experienced two high points at this time: the establishment of the General Study of Tudela in 1259 and that of the University of Oñate in 1540.

Sancho Garcés II "Abarca" (970-994) and Count of Aragon (943-994) was the first to call himself King of Navarre, according to the Annals of the Kingdom of Navarre: "reinando Yo, D. Sancho, King of Navarre, in Aragon, in Nájera and as far as Montes de Oca".

In the times of Sancho III the Greater (1004-1035) the domains of the Kingdom of Nájera-Pamplona, which included Navarre (except La Ribera), northwest Soria, La Rioja, the current three Basque provinces, Castilla, Aragón, Sobrarbe and Ribagorza from 1032 to 1035, reached their greatest territorial extension.

According to some historians (such as Ramón Menéndez Pidal or Justo Pérez de Urbel), Sancho III, the so-called Rex Navarrae Hispaniarum and Rex Ibericus was the first king aware of the "unity of Spain" forging the first "Spanish empire"; According to other Basque ideologies, he was the unifier of the Basque territories. In any case, the presumed Hispanic unification only lasted three years, since, upon his death, he divided his kingdom among his children. And the presumed Basque unification, five more years, since in the year 1040 the Lord of Biscay declared himself a vassal of the King of Castile.

After the death of Sancho III in the year 1035, his will, following the Navarrese tradition, transferred the kingdom to his eldest son, García "el de Nájera", having to render the rest of his sons vassalage to this [citation needed]("sub manu"), but what really happened is that these vassals created independent kingdoms establishing the new political structure of the century XII with the kingdoms of Nájera-Pamplona (later the kingdom of Navarre), Aragon and Castilla.

The decline of Navarre

Between 1076 and 1134 the kingdom of Nájera and Pamplona was incorporated into the Aragonese crown from which it separated in the reign of García Ramírez (see map 1097 AD).

In that of Sancho el Sabio (1150-1194) it was renamed Kingdom of Navarre and the territorial loss continued: in the year 1200, under the reign of Sancho el Fuerte (1194-1234), lost the current territories of Álava, Guipúzcoa and Duranguesado, which were conquered by the Castilian monarch when the Navarrese king was in Murcia, in search of allies (see map of the 12th century and map of 1190 AD).

The "Arrano Beltza", a "aguila negra" on a yellow background, seal of Sancho VII the Strong (1194-1234), is the current symbol of the most independent Basque nationalism.

The current coat of arms of Navarre, red with chains around a green emerald, arose in the mid-century XII, with the adoption of the heraldic fashion by King Sancho VI of Navarre (1150-1194) as evidenced by preserved copies of his personal seals. There is a legend that identifies these chains with which Sancho the Strong was supposedly taken as loot during the battle of Las Navas de Tolosa against the troops of Miramamolín in 1212. Sancho VII's successor, Teobaldo I of Navarre, instead adopted for his first seal the primitive forms of Sancho VI, whose arms began to be spread painted in the form of a defensive shield with the characteristic blocking of reinforcement. The drawing of this blockade evolved until it acquired an emblematic meaning and took the form of the celebrated "cadenas de Navarra".

Navarra, already separated from the other peninsular territories of Euskal Herria, is forced to direct its expansion policy towards the north and east, Basque-French territories of Ultraports, and the border strip with Aragon.

The death without issue of Sancho VII the Strong, despite having left a pact of adoption with Jaime of Aragon, means the enthronement in Navarre for almost two centuries of French dynasties (the Champagne, the Capeta and the Evreux) who will also have territories in France and will neglect to varying degrees the government of the small kingdom.

Castilian, the administrative language of the time, worked with difficulty in 1219 among the rural population. Thus, the multiple lawsuits such as the privilege granted by the Merino Mayor de Castilla to the residents of the Riojan valley of Ojacastro, to be attended in Basque.

The pressure of Castile and Aragon means that, seeking the survival of the kingdom, on the death of Sancho VII el Fuerte in 1234 without issue, he enters the orbit of France with the installation of the house of Champagne (1234-1274) and, later, of the Capetians (1274-1328). The house of Évreux (1328-1425) (see map 1360 AD) inaugurated a period of interesting peninsular and European relations, especially with Carlos II. Carlos III the Noble (1387-1425) (see map 1378-1417) stands out for the material and cultural prosperity that developed in Navarre.

When Carlos III died, the turbulent reign of the Aragonese infant Juan II (1425-1479) began, which would lay the seed for the future disintegration of the kingdom (see 15th century map). Juan II was married to the holder and heiress to the crown, Blanca I of Navarra. Blanca's will, made in 1439, two years before her death, established that Prince Carlos de Viana should not wear the crown without the consent of his father, who would never grant it. Thus, Carlos de Viana reluctantly served as lieutenant of the kingdom, while his father, the ambitious infante Juan, took a prominent part in the Castilian noble league against the favorite Álvaro de Luna, succeeded his brother Alfonso the Magnanimous in the Aragonese crown (1458) and married Juana Enríquez (1447), daughter of the Admiral of Castilla in order to shore up his position within the Castilian noble league. The marriage decreased his rights to maintain the Navarrese crown, since he maintained it as the widowed king of the crown holder, but when he married again he ceased to be so.

Carlos de Viana held the lieutenancy of the kingdom peacefully until 1449. That year, his father returned to Navarra and took control of the government, suppressing the lieutenancy. In addition, he placed addicted people, contrary to the Beaumontés faction, which supported the prince, in the key positions of the administration. The Navarre Civil War finally broke out in 1451 with two clearly differentiated sides. The people from Agramonte supported Juan II of Aragon and the Beaumont people supported Carlos de Viana. The two sides clashed in the battle of Aibar (October 25, 1451) resulting in the prince being captured by his father. The prince would remain in prison until 1453 and would be disinherited by his father two years later.

The war was won by Carlos de Viana, but he died under strange circumstances (rumors spread that he had been poisoned by Juana Enríquez). Thus, with the reign of his sister Eleanor, the Foix dynasty entered, although a generation later it would change to Albret, with the marriage between Catalina de Foix and Juan III de Albret.

The conquest of peninsular Navarre by Castile

Between 1512 and 1524 the Conquest of Navarre took place in which Ferdinand the Catholic (son of Juan II and Juana Enríquez) and king consort of Castile, militarily invaded Navarre (see map 1560 AD) with powerful troops under the orders of the Duke of Alba. This time the people of Agramonte opted for the legitimate Kings of Navarre (Catalina and Juan) and the Beaumonteses for Ferdinand the Catholic. And so Fernando the Catholic managed to occupy the Kingdom of Navarre with the support of Pope Julius II, alleging that the Navarrese kings were allies of Louis XII of France, an enemy of the Holy League, in which both Spain and the Papal States participated. In 1515, by the Treaty of Burgos, Navarra was annexed by the Crown of Castile. No Navarrese was present at this meeting. Years later, first Juan de Albret and later Enrique II of Navarre tried to recover the Navarrese territory south of the Pyrenees but it was not possible before the arrival of winter. In his withdrawal, the rear of Albret's army was attacked, producing the so-called battle of Velate where some valuable cannons were requisitioned and the degree of confrontation that occurred is not clear to historians. The most important attempt was made in 1521 when Carlos I of Castile was already reigning (and taking advantage of the war in the Communities of Castile). It was managed to recover in a short time, thanks to the general uprising of the Navarrese of almost all of Navarra. Subsequently, on June 30, 1521 (the war in Castile had ended), the Battle of Noáin took place, where the defeat of the Franco-Navarre troops determined the fate of Navarra. There were still two pockets of resistance: one in the Battle of Amaiur (1522), where today a monolith commemorates the battle, and the end of the independence of Navarra, and another, until February 1524, in the Castle of Fuenterrabía.

The Kingdom of Navarre under the domain of the house of Albret-Foix was reduced to the territories to the north of the Pyrenees (Lower Navarre) (see previous map). In 1594 Enrique de Navarra was crowned King of France, being the first Bourbon to accede to the French throne.

The privileges

For a long time, each one of the Basque territories, the cities and the towns conserved their different particular jurisdictions (in Vizcaya the jurisdiction of Vizcaya for the flat land of Vizcaya, the Duranguesado and the Encartaciones for these two since the end of the century XVI, jurisdiction of Logroño for Bilbao or Bermeo, etc.; in Guipúzcoa the jurisdiction of Guipúzcoa; in Álava the jurisdiction of Ayala and that of Vizcaya; in Navarra that of Navarra; etc.), which were not abolished by the Spanish and French kings.

The situation changed with the French Revolution. In the French territories, north of the Pyrenees, the fueros were immediately repealed.

The southern part, the Spanish part, was one of the main scenarios of the Carlist Wars where the urban population supported the Liberals and the rural population supported the Carlists. Different brawls, in addition to the Carlist Wars, occurred since the announcement of the suspension of the fueros. The result was the loss of a large part of the privileges of the Basque Provinces in 1876 after the Carlist defeat.

In Navarre, however, a law made it possible to preserve a large part of the original fueros. This was due to the enthusiasm of the Navarrese elite with liberalism, which created a doctrine called liberal fuerismo where they advocated adapting the fueros to the liberal State.

Ethnography

José Miguel de Barandiarán, a teacher in Basque anthropology, ethnography and mythology expressed the following about the Basque people:

The Basque people are currently a perfectly defined ethnic and cultural group. There are many different facts that have contributed to the profile of his personality and have given him a characteristic nuance. Such events spring from the life and culture of the Basque people. And this culture and this life have its history, which, not in isolation, but constitute an organic process, articulated with the vicissitudes of other peoples, form Basque history.

The words of Andrés Ortiz-Osés, a member of the Círculo de Eranos, are also explanatory in this regard and justify the differences with respect to the Indo-European peoples:

Today the Basque indigenous culture represents the last reduct in the context of the patriarchal-rationalist indo-European culture. The Basque indigenous culture, in fact, is pre-indoeuropea and pre-patriarchal: the Basques, from an indigenous Pyrenean evolution of Crogmanon, existed as such an ethnic group before the famous patriarchal invasions of the Indo-Europeans.

For this reason, its peculiar characteristics were the object of attention of international researchers among which the German Wilhelm von Humboldt stands out, whose visits Arturo Farinelli recounts.

Language

The Basque people have their own language, Euskera, apart from Spanish and French. We also find Gascon and Roma in a much smaller minority that some of the autochthonous gypsies have preserved.

Today, practically all Basques speak the respective state languages (Spanish and French). In all of Euskal Herria, approximately one third of the Basques speak Euskera, a non-Indo-European language. This unique and isolated language has caught the attention of many linguists, who have tried to discover its history and origin.

In the Lower Adour area, which includes the towns of Bayonne and Anglet, Gascon (a dialect of Occitan) is the traditional language (the Basque spoken today was introduced from the XIX due to the migration of the Basque-speaking population from the interior) and French. Because of this, this area is considered by Occitanists as part of Gascogne and is currently a trilingual area.

The Basque-speaking population is on the rise, mainly due to the co-officialization of Basque in the three territories of the autonomous community of the Basque Country, its support and promotion by the institutions and its implementation in the educational system. In Navarra, Euskera is considered its own language along with Spanish, although it is not co-official throughout the territory, while in the French Basque Country it is not even official, although its teaching is allowed.

In 2003, the Department of Culture of the Basque Government highlighted that while in the Basque Country the percentage of the Basque-speaking population rose 5 points, in Navarra it barely rose 1, while in the French Basque Country it fell 9 points. This made an increase of 3 percentage points in total.

The "IV Sociolinguistic Survey" of the Basque Government carried out in 2006 points out that six out of ten Basques have some knowledge of Basque and it had gained 137,000 speakers in the last fifteen years, although unevenly. It confirmed that the revitalization of the Basque language was advancing in the autonomous community of the Basque Country, especially in Álava, rising from 7.8% to 14.2%, and in Navarra, while in the French Basque Country it continued its decline, going from 24.4% to 22.5%, although the regression slowed down. Knowledge of Basque was increasing, especially among the young population, in all territories.

In 2008 there was a growing increase in the population that studied Basque in Navarra, with the percentage of people who had knowledge of that language in Navarra remaining at 18%, in Guipúzcoa 52%, and 31% in Vizcaya and in Álava 25%.

Related articles

- Alavese Dialecto

- Vizcaino Dialecto

- High-navar Dialecto

- Dialecto bajo-navarro

- Dialecto suletino

- Dialecto labortano

- Gipuzka Dialecto

- Dialecto roncalés

- Euskera Battery

Basque mythology

Basque mythology is a pre-Indo-European and matriarchal mythology, with the Goddess Mari being the central motif around which many of its legends revolve. Its priestesses, the sorginak, were demonized with the arrival of Christianity and persecuted, as in the case of Zugarramurdi, although this did not prevent the family cult of ancestors from continuing to be led by the etxekoandre (the mother of the home or hamlet) and their medicine practices were resumed by the emaginak (midwives).

Other figures to highlight are the lamiak or laminak, numenas that inhabited the banks of the rivers, and the jentillak (literally, pagans); Of the latter, only the Basajaunak (lords of the forests) and Olentzero, who converted to Christianity, survived the advent of Kixmi (Christ).

The influence of Indo-European beliefs is different depending on the historical territory in certain cases, because while in most cases the Sun is treated as a feminine divinity (Eguzki amandrea or grandmother sun) to whom we pray when worn and treated with respect, in Vizcaya, probably due to Celtic influence, it took the form of a masculine genius under the name of Ekhi.

These beliefs have survived until the 20th century at the hands of Basque artists who were born and raised with the magic of mythology such as Néstor Basterretxea or Patxi Xabier Lezama Perier with interpretations of the ancient Basque mythological gods, many times independently in tales or legends and in other cases in idiosyncrasy with Christian beliefs, where the pagan was persecuted and identified with the Devil. In the study of Basque mythology, the work carried out by anthropologists such as Joxemiel Barandiaran, José María Satrustegi and Caro Baroja should be highlighted.

Basque rural sport

Among the traditional and typical sports we find Basque pelota and rural Basque sports that are deeply rooted throughout the Basque Country.

Basque pelota is another characteristic sport of the country. It is played in the pediments, with different traditional modalities, being the ball by hand, basket-punta, ski lift, shovel and ratchet the best known. This sport has spread throughout the world, especially in Hispanic countries, having a relevant presence in Florida (USA). There are important frontons in the main cities of the Hispanic world, including the Jai Alai in Manila. The pelotatzale (ball) hobby is widespread throughout a good part of the north of the peninsula, and even finds fans in Valencia.

We must not forget the Basque tradition of the boat regattas, which together with other Cantabrian towns carry out a circuit of championships disputing the famous "flags", for the Basque Country with the participation: C.R. Arkote, Plencia (Vizcaya), Hondarribia A.E., Fuenterrabía (Guipúzcoa), Zarautz Inmobiliaria Orio, Zarauz (Guipúzcoa), C.R.O. Orio, Orio, (Guipúzcoa), Getariako A.E Guetaria, (Guipúzcoa), Pasai Donibane, Pasajes (Guipúzcoa), Zumaya (Guipúzcoa), Urdaibai A.E., Bermeo (Vizcaya) and Kaiku A.K.E (Sestao) (Vizcaya).

Other traditional Basque sports or rural sports are linked to work in the farmhouses (baserriak) and the Basques' fondness for challenges between different athletes in the area, in which bets were exchanged between neighbors in favor of one of the contenders, this tradition is still preserved today, betting being a very important component in Basque rural sports events (also in Basque pelota). The main Basque rural sports that are still preserved are: stone lifting, where the record exceeds 300kg (harrijasotzaileak), log cutting (aizkolariak), grass cutting (segalariak), taking the rope one of the two teams pulling each one of them from the middle to one of the two ends (soka-tira) and the tests of dragging large stones with a team of oxen (idi-probak).

Dances

Basque dances are a very important part of Basque culture and folklore. Each town and village has its own dances, which, although they have been studied by territory, do not always imply a direct relationship between them. The first studies of these dances date back to Manuel de Larramendi and his Choreography or general description of the very noble and loyal Province of Guipúzcoa (1756), although there is evidence of these as early as the 17th century. style="font-variant:small-caps;text-transform:lowercase">XVI, as these accompanied the astolasterrak, popular theater pieces with a humorous tone.

Focusing on the different types of dance, three characteristic formations of performance cannot be overlooked:

- Dances of pilgrimage or square, based on the dances that were celebrated in the pilgrimages and whose participation was popular and spontaneous have gone to thicken the repertoire of the established dance groups, although it is true that they are still being carried out in all those pilgrimages, especially in the rural places of the country, this kind of popular and spontaneous dances that invite all the pilgrims and visitors to participate freely.

- Sword dancesThe sword dances, which have an obvious parallelism with the Europeans of the same kind. Its realization, always linked to the commemoration or to the surrender of honors, is linked to the ritual dance where the people respectfully support each group of dancers.

- End party dances, this type of dances are made to mark the end of a holiday or of a specific period, such as the carnival, have served as symbolic colophon to the festive rampage, represented in the coupo, vapuleo and burning of the skin of inflated and empty wine. It is the end of one cycle and the beginning of another.

Culture

Literature

"The history of the Basque literature is nothing more than the history of the effort of a scarce people in inhabitants, politically disarticulated and mistreated and culturally devoid, to approach the written tradition" |

| Patxi Salaberri, member of the Navarro Council of the Euskera and academic number of Real Academia de la Lengua Vasca. |

The main characteristics of literature in Basque are the following:

- It is the fruit of a language without officiality or unity: having been born in such a small community of speakers has had an important impact on the written literature, especially as history and the limits of the languages and peoples progress are weakened and diffused. The history of the Basque language is said to be is the story of its survival and that of a people which will mark all the authors, turning together with the religious theme the commitment (whose first steps would be the apologism of Larramendi) towards the euskera one of the pillars around which different movements will revolve.

- Born among states whose languages are romances: Euskal Herria is among what has been the cultural and political centers of the West, being these competing states among themselves depositaries of the Latin tradition. That is why this people who have kept their old speech have received the Latin influence, which is reflected above all in the School of Sara and other religious authors of the time because of the abundant use of quotes to classic and Christian authors that they did in their prose texts.

- The main purpose of religious teaching: Father Barandiaran (as Martin Ugalde collects in his Synthesis of the history of the Basque Country or the same religious in his Early Men in the Basque Country) defended in life the late Christianization of the Basque people, claiming that in the same Navarre until the centuryXX. pagan beliefs had been preserved in idiosyncrasy with the Christians. This is the reason behind the insistence of the Catholic Church for Christianizing and extending catechism among the people using the Basque language (after the Counter-Reform). This religion was sometimes imposed by the politics of the moment, but on other occasions the Catholic Church itself used the language itself (the Basque) and literature as a wall against the changes and new ideologies arising, this would be the case of Protestantism or journalistic clashes of Jean Hiriart-Urruti and the French republicanists.

- Poetry has always had more weight than prose: so it has been the beginning of most languages, because the prose demands a reader, that is, alphabet people who read it. The songs, bertsos, esiak and songs, have only needed to be sung. That is why, as in other literatures, the coplas and songs of melodies that were and are known to the people are abundant. The fruit of this would also be the abundance of lyrical compositions of a popular character, in front of the cultured poetry, which almost until the end of the XIX would not get rid of the influence of bertsolarism in the use of meters above all.

- Little implantation of the printing press or the "problem of the printing press": unlike the rest of the Romantic languages the printing press apparently had little implantation so that non-religious works like Peru Abarca they had to be transmitted through manuscripts even in the late 18th century. There has been much debate and a little clear, on the one hand, the existence of censorship both in France and in Spain over the centuries following the western schism, on the other hand that there was not enough production for the implementation of these or the lack of need of these by the authorities, which would have been validated from other means to transmit real and similar edicts. As evidenced by the publication of real edicts in euskera during the Kingdom of Navarre, the printing press had been implanted in Vasconia, therefore one of the arguments would be rejected (although most religious texts were published outside Euskal Herria and the existence of an edict of 1766 of the Earl of Aranda prohibiting publication in euskera (1766)) [chuckles]required], but that of censorship would gain strength in the light of the long periods that passed the works between which they were written, passed the censorship of the inquisition and finally published. This was the case of Juan de Tartas, whose works, despite being religious, took time to be printed and (as in the case of other authors of the time) suffered the so-called "bad of printing". That is, the alteration of the work due to the frank spelling and the suppression of most of the punctuation signs, to the point of being extremely complicated his reading and understanding.

- Your study is relatively recent: Excepting the case of Oihenart perhaps, there has been no author until well entered the centuryXIX that has been interested in the history of the literature in Basque, which added to the problem of the printing press has made discoveries such as the manuscript of Joan Amendux (1969), Ibarguen-Chopin or Lazarrraga (2004) have revolutionized what was known so far, especially regarding the late medieval and pre-rerenaissance literature.

Written Literature

The first book published in Basque was Lingua Vasconum Primitiae by Bernard Etxepare in 1545. This work is known from the only copy preserved in the National Library in Paris. As can be inferred from the opinions of his contemporaries, he was not appreciated due to his popular meters of bertsolarism. His verses were set to music at the end of the XX century by Benito Lertxundi, Xabier Lete and the group Oskorri, among others, turning them into songs popular. Currently his poems have acquired the character of almost an anthem among the sectors of the Euskaldun culture and in defense of the Basque language, being recited in all kinds of cultural and popular events.

- CONTRAPAS

|

|

Education

The educational system is regulated by the general laws of the two states. Then, in the Spanish part, each autonomous community has its own particularities, while in the French the system obeys the general legislation of France. In all of them schooling is compulsory up to the age of 16.

Gastronomy

The gastronomy of all the territories that make up the Basque Country enjoys great prestige both nationally and internationally.[citation required] Both in the French part, where the recognized category of its cuisine extends to them, as in the autonomous communities of Navarra and the Basque Country on the Spanish side.

The gastronomic societies stand out.

Skewers are undoubtedly a very popular and appreciated specialty; also any of the preparations of cod or cocochas, which are some of the most popular Basque cuisine specialties on the coast. In the mountains you can highlight the cheese with denominations such as Idiazábal, Roncal or Ossau-Iraty, the curd (typical of the entire Cantabrian coast, especially Cantabria) (the one from the Ulzama valley is famous), the chistorra from Navarra and the veal. In the south, the piquillo peppers from Lodosa, Navarrese and Rioja Alavesa wines, and natural asparagus stand out. In the north, the Espelette pepper, the piperrada, the Irouléguy wine, the Basque cake (gâteau basque in French) or the axoa are very famous.

Celebrations

Within the common tradition, with a greater or lesser presence, the following festivities are celebrated, some of them of a political nature and others of a cultural nature.

- Tamborrada de San Sebastian: January 20 in San Sebastian.

- Vespera de Santa Águeda: February 4.

- Inauteri: Carnivals, late winter. From the ethnographic point of view, the carnivals of small rural nuclei such as Lanz, Ituren, Zubieta have special interest...

- Aberri Eguna: Day of the Basque Country (initially the PNV), Resurrection Sunday.

- Nafarroaren Eguna: Last Sunday of April in Baigorri.

- Sanfermines: from 6 to 14 July in Pamplona.

- San Ignacio de Loyola: pattern of Guipúzcoa and Vizcaya. 31 July

- Bayonne Festivals: from 24 to 28 July in Bayonne.

- Suletine pastoral: Theatrical work typical of Sola during the summer.

- Fiestas de La Blanca de Vitoria: from 4 to 9 August in Vitoria.

- Big Week of San Sebastian: August 15th Week in San Sebastian.

- Bilbao's Great Week: the second half of the month of August in Bilbao.

- San Francisco Javier: patron of Navarre and International Day of the Basque Country. December 3.

- St. Thomas Day: holidays marked by the rural environment. 21 December in several municipalities of Vizcaínos and Guipuzcoanos.

- Olentzero: Christmas character that runs through the streets in Euskal Herria on 24 and 25 December.

Sports

The non-traditional sports activities as well as the interest in them are greatly influenced by the interest of the media of each state to which each territory belongs, therefore, while in the territories In Spain, the majority of fans favor football and cycling, while in the French, rugby is one of the most followed and practiced sports.

- Football is the main Basque sport as it is in Spain and France. The main clubs are Athletic Club, Real Society, Eibar, Osasuna and Alavés. The Athletic Club of Bilbao maintains a policy of registering only Euskal Herria players, or well formed in the quarry of some Basque club.

- Cycling is another popular sport. Not in vain the production of bicycles in Spain has been centralized for a long time in these territories, especially in Éibar, where they were organized in the mid-centuryXX. the first cycling tests. In the competitions you can see Basque followers dressed in orange, the color of the Euskaltel-Euskadi team and are already mythical the ikurriñas present always in the mountain stages of the "Tour de France", proof in which the cyclist of Villava, Miguel Indurain, already retired from the competition, was the first to win the Tour de France five consecutive times, winning also the Giro de Italia. Also the cyclist Abraham Olano won the Return to Spain and was world champion on the road.

- In the French Basque Country, rugby is very popular among the Basque community. In France, rugby is a popular sport in the southwest. Two Basque clubs belong to the first division of the French rugby league (the Top 14): the "BOPB" or the "Biarritz Olympique Pays Basque" in Biarriz and the "Aviron Bayonnais" in Bayona. The colors of the Biarritz Olympique are red and white and those of the Aviron Bayonnais, white and blue. There are also national-level clubs (Fédérale 1 equivalent of the third division) in Mauleon (Sola) (Sport Athlétique Mauléonais), in San Juan Pie de Puerto (Baja-Navarra) (US Nafarroa) and San Juan de Luz (Labort) (Saint Jean de Luz Olympique Rugby).

- As for the mountain and climbing, the vitoriano Juanito Oiarzabal (Vitoria), who has the world record of "ochomiles", with 24 in total. Also noteworthy, Josune Bereziartu, the only woman who has climbed grade 9a/5.14d; Edurne Pasaban, the first woman to climb the 14 eight thousand; we wound them Eneko Pou and Iker Pou and the world champion, in 2006, in sport climbing the eibarrés Patxi Usobiaga, named "best Basque sportsman of 2006" and World Cup champion that same year.

- The Laboral Kutxa Baskonia de Vitoria is a very outstanding team in basketball and in its palmarés presume to be two times Euroliga subfield, European Cup champion and four times subfield, league champion and three times subfielder and has six King Cups of Basketball and three subfielders. There are also basketball teams in San Sebastian (Gipuzkoa Basket), Bilbao (Dominion Bilbao Basket) and Hondarribia-Irun (Liga Femenina).

- In basketball the star is the AMAYA Sport San Antonio de Pamplona, which has won the Cup of Europe (2000/01), being a champion of the same in 2002/03 and 2005-06, Recopa de Europa (1999/00 and 2003/04), Champion of League (2001/02 and 2004/05), sub-campion of league (1997/98 and 1999/00), of the Copa del Rey (1998/99 and 2000/01), the champion). Also noteworthy are the eibarrés Juventud Deportiva Arrate that is held in the Spanish Honor Division, and the Bidasoa Sports Club of Irún, which currently militates in the Honor B Division but which got the European Cup (1994/95), this being the first title in a sport for teams for a Basque club, sub-campaign of the same in the 1995/96 season. Champion of the Recopa of Europe 1996/97, Champion of League in the 1986/87 and 1994/95 seasons, champion of the Copa del Rey 1990/91 and 1995/96, champion of the Supercopa of Spain 1995/96 and of the Asobal Cup 1992/93.

- The exceptional conditions in the Basque coast for the practice of surfing with places like Zarauz, Mundaca and Biarriz, which are often on the world surf circuit.

Political parties

For years, the independence, or greater autonomy, of the Southern Basque Country or Hegoalde has been at the center of Basque politics in Spain, the Basque political parties state:

- The Basque Nationalist Party defends “the right of the Basque people to decide their future” and the achievement of a “new status” for the Basque people.

- Euskal Herria Bildu: a stable coalition belonging to the so-called abertzale left-wing pole, made up of the Sortu, Eusko Alkartasuna, Aralar and Alternatiba parties and the Herritarron Garaia and Araba Bai groups. It promotes the independence of Euskal Herria.

- The Basque Nationalist Party, Eusko Alkartasuna (EA), Aralar, Sortu and Abertzaleen Batasuna among others, defend independence through the right of self-determination.

- Elkarrekin Podemos defends that "Euskadi is a nation" and the right of the Basques to decide their future.

- Geroa Bai, the Navarre coalition heir to Nafarroa Bai, defends from the prisma abertzale also respect for the will of the Navarre to decide their future.

- Socialist Party of Euskadi-Euskadiko Ezkerra (federation of the Spanish Socialist Workers Party) advocates for a Federal Spain; that would change the current status.

- The Popular Party opposes any change in the current status.

- Unión del Pueblo Navarro proposes that Navarra be a differentiated community within Spain, as well as reject a possible union with the Basque Country. Since 1982, the Socialist Party of Navarre defends Navarre as a differentiated community and opposes the union with the Basque Country.

- Izquierda Mirandesa, Agrupación Electoral Independiente del Condado de Treviño y Agrupación Electoral Independiente de la Puebla propose that the region of Miranda de Ebro and the Treviño County belonging to Burgos be integrated in the province of Álava. In all cases the idea of Basque independence is defended, and they support the independence of Euskal Herria, a territory to which they belong.

- Other positions: Alternatiba, Batzarre, Izquierda-Ezkerra, Ezker Batua-Berdeak, the Carlist Party of Euskalherria.

The debate in the French Basque Country or Iparralde is different and focuses on the institutional articulation of the Basque Country, whose main claim was that of a Basque department or the recognition of autonomy.

With the reform of the territorial model in France, the demand has focused on the creation of a Territorial Collectivity on the map of the French administration. This demand had an unprecedented consensus to date, but was met with rejection by the French government. Finally, the French Basque Country was constituted as a unified commonwealth with powers in economic development, transport, waste collection and language policy.

Personalities of different political sensibilities have supported the claim of the Territorial Collectivity, such as Jean-René Etchegaray, mayor of Bayonne, Jean-Michel Galant, president of the Baigorri-Garazi community; Max Brisson, secretary of the UMP; the centrist senator and president of the Elected Council of Iparralde Jean-Jacques Lasserre; the deputies of the Socialist Party Sylviane Alaux and Colette Capdevielle; the senator and parliamentary spokesperson for the Socialist Party Frédérique Espagnac or the mayor of Hendaye, Kotte Ezenarro.

- The Republicans and formerly the Union for a Popular Movement oppose self-determination, and the autonomy of the French Basque Country The former mayor of Baiona Jean Grenet said the Basque Department "It is not the engine of decentralization"but supported the Council of Elects in its demand to fit the Basque reality into the "metropolitan pole". During the recent debate of the territorial collectivity the leader of the UMP in the Basque Country, Max Brisson, was favorable to the creation of the territorial collectivity.

- The Socialist Party, during Francois Mitterrand's mandate, promised the creation of a Basque Department that finally failed to fulfill after his election. Basque socialist political representatives such as Frantxua Maitia, Kotte Ezenarro or the Sylviane Alaux, Colette Capdevielle and Frédérique Espagnac are favorable to institutional demands and have been very active in their achievement, other positions like Jean Espilondo were opposite.

- The centrists are also divided. The main institutional position of the centrists, the mayor of Bayona Jean René Etchegaray, was elected president of the Commonwealth of the Basque Country.

- Basque nationalist parties, such as Euskal Herria Bai (which encompasses Abertzaleen Batasuna, Sortu and Eusko Alkartasuna) and the Basque Nationalist Party have always called for the creation of an institution for the Basque Country. Although the Basque Department was called for, in the face of the Territorial Reform, the Basque nationalists claim their own institution through autonomy. EA, Abertzaleen Batasuna and Sortu form the Euskal Herria Bai coalition, which assumes these declarations. Some political formations at the French state level, such as Europe Ecologie, also endorse the Basque institutional claim. Basque nationalists have also supported the creation of the single community, although their aspiration is to advance the autonomy.

- Front National maintains a French centralist and identity policy, opposed to the institutional recognition of the Basque Country.

- Batera is a platform that promotes popular consultations on Autonomy for the French Basque Country.

- Enbata was an abertzale political movement that called for the creation of its own department for the French Basque Country within the French constitution and the creation of a common autonomous entity for the seven Basque historical territories.

Wildlife

Among the breeds of farm animals typical of the territory are those mentioned below. Within the bovine breeds: the betizu, the monchina, the Pyrenees and the terreña; within the goat breeds: the azpi-gorri; within the sheep breeds: the carranzana, the latxa and the sasi-ardi; within the equine and donkey breeds: the donkey, the Alava horse and the pottoka; Within the pig breeds: the Vitoriano snub; within the canine breeds: the Basque shepherd, the villain of the Encartaciones, the Pachón de Vitoria and the villanuco of the Encartaciones.

Contenido relacionado

Walloon language

Folk music from Spain

Bojutsu