Baruch Spinoza

Baruch Spinoza (Amsterdam, November 24, 1632 - The Hague, February 21, 1677) was a Dutch philosopher of Spanish-Portuguese Sephardic origin. He is also known as Baruch, Bento, Benito, Benedicto or Benedictus (de) Spinoza or Espinosa , according to the different translations of his name based on the hypotheses about his origin. A critical heir to Cartesianism, he is considered one of the three great rationalists of 17th century philosophy, along with the French René Descartes and the German Gottfried Leibniz, with whom he also had a small correspondence.

Spinoza was raised in the Jewish-Portuguese community of Amsterdam. He developed highly controversial ideas regarding the authenticity of the Hebrew Bible and the nature of the one divinity. The Jewish religious authorities issued a cherem against him, which caused him to be expelled and shunned by Jewish society at the age of twenty-four (1656). He then resided in The Hague, where he dedicated himself to working as a lens polisher.

In philosophy, he is one of the main representatives of rationalism. His magnum opus, the Ethics, was published posthumously in the same year of his death (1677). The work is characterized by a rationalism that opposes the dualism of Cartesian mind and body.

Some commentators have suggested a pantheistic interpretation of Spinoza's philosophy, holding that there is an identification between the only reality (substance) and "God" or "Nature" (pantheism). In this interpretation, reality is eternal, infinite and perfect, but very different from the personal god of classical theism, and all things in the universe are simple "modes" of God, therefore, everything that exists tends to persevere in its being (conatus), in the case of the human being it manifests itself as the desire to live according to the opinion of his reason.

In his Theological-Political Treatise (1670) he critically analyzed the Judeo-Christian religion, and defended the "freedom of philosophizing" and democracy. His political theory unified the purpose of the State and the ends of the individual (preserving his rational being) through the social order, political authority and laws.

Spinoza was frequently attacked for his political and religious views. His contemporaries frequently called him an "atheist," although he did not deny the existence of God in any of his works. Harassed for his criticism of religious orthodoxy, his books were included in the Catholic Church's Index librorum prohibitorum (1679). 19th century: "Schleiermacher [...] Hegel, Schelling all proclaim with one voice that Spinoza is the father of modern thought". His philosophical and moral achievements led Gilles Deleuze to name him "the prince of philosophers".

Biography

Family origins

He was born in Amsterdam (The Netherlands) in 1632, coming from a family of Sephardic Jews emigrants from the Iberian Peninsula, fleeing religious persecution.

His family roots can be found in Espinosa de los Monteros, where the last name of his relatives was "Espinosa de Cerrato". The Espinosas were expelled from Castile by the decree of the Catholic Monarchs on March 31, 1492, and decided to settle in Portugal. There they were forced to convert to Catholicism to continue remaining in the country when Manuel I of Portugal, the Fortunate, married Isabel of Aragón, eldest daughter of the Catholic Monarchs, and ordered the Jews who held important positions in the country to be baptized. by force (doctors, bankers, merchants, etc.). At that time one hundred and twenty thousand Jews converted and the Espinosas were able to live in peace until the Inquisition established itself in Portugal some forty years later.

Spinoza's grandfather, Isaac de Espinosa, went to Nantes (his presence is attested in 1593), but he did not stay there, because Judaism was officially banned and because of the hostility that existed towards the "marranos" and especially to the Portuguese. Apparently expelled in 1615, he arrived in Rotterdam with his family, where he died in 1627. Gabriel Álvarez, Isaac's father-in-law and Spinoza's paternal great-grandfather, was sentenced to death on 20 August 1597 by the Portuguese Inquisition, although said penalty would be commuted to one of galleys.

His father, Miguel de Espinosa, was a renowned merchant and an active member of the Jewish community (synagogue and Jewish schools).

Education

Spinoza was educated in the Jewish community of Amsterdam, where there was religious tolerance, despite the influence of Calvinist clerics. Despite having received an education linked to Jewish orthodoxy, for example, by attending the lessons of Saúl Levi Morteira and Rabbi Menasseh Ben Israel (the man who negotiated with Cromwell for the return of the Jews to England), He demonstrated a rather critical attitude towards these teachings and was self-taught in mathematics and Cartesian philosophy, with the help of Franciscus van den Enden, who gave him not only Latin lessons from the age of eighteen, but "new science" instructing him in the ideas and works by Copernicus, Galileo, Kepler, Harvey, Huygens, and Descartes.

He also read Thomas Hobbes, Lucretius and Giordano Bruno, and these readings led him away from Jewish orthodoxy. To this, we can add the influences of the group of collegianten (collegiants), Dutch Protestant liberal Christians, as well as Spanish-Portuguese Jewish heterodoxies represented mainly in the figures of Juan de Prado and Uriel da Coast.

Expulsion from the Jewish community

After his father died in 1654, the philosopher no longer had to keep his disbelief hidden out of respect for the father figure.[citation needed] Then he found himself involved in a lawsuit with his stepsister regarding his father's inheritance. Baruch having won, he nevertheless renounced his large inheritance, taking only "a good bed, with its linen". In the course of the lawsuit, Spinoza's orthodoxy was called into question. The synagogue leaders offered him a pension of nine thousand guilders if he would leave Van den Ende and return to Orthodox Judaism; but Spinoza did not relent, and on July 27, 1656, the Amsterdam Talmud Torah congregation issued an order of cherem (Hebrew: חרם, a kind of prohibition, rejection, ostracism, or expulsion) against Spinoza, then twenty-three years old. The anathema in question was originally written in Portuguese, the translation of various fragments of the text is as follows:

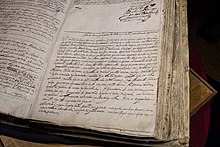

[...] for a long time [we had] news of the wrong opinions and wrong conduct of Baruch of Spinoza and by various means and warnings have tried to turn him away from the wrong path. As they did not obtain any result [...] they resolved [...] that this was [...] expelled from the people of Israel, according to the following decree [...]: [...] we expelled, execrated and cursed Baruch of Spinoza [...] before the Holy Books of the Law with their [six hundred thirteen] prescripts, with the excommunication with which Joshua excommunicated Jericho, with the curse with which Elisha written and cursed Cursed be day and cursed be night; cursed be when he lies down and cursed be when he rises; cursed be when he comes out and cursed be when he returns. May the Lord not forgive him. May the wrath and anger of the Lord be set against this man and cast upon him all the curses written in the Book of the Law. [...] We order that no one keep with him oral or written communication, that no one lends him any favor, [...] that no one reads anything written or transcribed by him.Cherem against Spinoza in the Book of the Nation Agreements.

He was then banished from the city, which was divided into two groups:

- Ashkenazis: Jews from Central Europe who, in suffering severe persecutions during the Middle Ages, emigrated in mass to Eastern Europe, but also to the Netherlands and England.

- Sephardic: Jews expelled from the Iberian Peninsula and group to which Spinoza belonged. It was a group partially influenced by humanistic tradition.

The Ashkenazim were a closed group. At some historical moment it seems that their rules were more orthodox and rigid than those of the Sephardim. It was the majority group in Amsterdam.

After the expulsion, he retired to a suburb on the outskirts of the city and wrote his Apology to justify his abdication from the synagogue, a lost work that some authors consider a precedent of his Theological-Political Treatise (TTP). In addition, he maintained his relationship with the Mennonite and collegiate Christian groups, of a fairly liberal and tolerant Christian character.

In accordance with the Jewish custom of having a trade to support himself, he had learned to polish glass lenses for optical instruments, especially for his friend the scientist Christiaan Huygens. Apart from making a living with this work, he received, according to some of his biographers, a pension that his friend Johan de Witt obtained for him.

Writing his works

In 1660 he moved to a house in Rijnsburg, a coastal town near Leyden, which is now a museum dedicated to the philosopher and where he wrote his exposition of Cartesian philosophy, entitled Renati des Cartes Principia Philosophias (Descartes' Principles of Philosophy, PPC), with the appendix of the Cogitata Metaphysica (Metaphysical Thoughts, CM), published in the boreal summer of 1663 (Latin ed.; in 1664 the immediate Dutch version appeared); these were the only two works published under his name during his lifetime. Its impact was so great that it made its author famous, whose house began to be frequented by all sorts of figures from the Dutch Golden Age, including Huygens and Jan de Witt. It is also believed that it was then that he composed his Short Treatise on God, Man, and Their Happiness. There he began an extensive correspondence with intellectuals from all over Europe, especially a fifteen-year one with Henry Oldenburg, a German diplomat who was in London and one of the secretaries of the Royal Society. In the early 1660s, he also began work on his Tractatus de Emendatione Intellectus (Treatise on Reform of the understanding, TIE) and in the most famous of his works: the Ethics (E), completed in 1675.

In 1663 he moved to Voorburg, near The Hague, where he frequented liberal circles and became close friends with the physicist Christiaan Huygens and with the then head of government (raadspensionaris) Jan or Johan de Witt, who offered his help regarding the anonymous publication of his Theological-Political Treatise (TTP) in 1670, a work that caused quite a stir for its criticism of religion. These diatribes against the TTP, and also the barbaric murder of his protector and friend De Witt in 1672 after the defeat of the Dutch army by the English, which was taken as divine punishment because of the statesman's tolerance of disbelievers ―crime condemned by Spinoza with the pasquin Ultimi barbarorum―, they convinced him not to publish new books as long as he lived; the works would circulate in handwritten copies without printing permission among his admirers. In the following years his isolation worsened and, given the fear for his own life, at the beginning of 1673 he would come to negotiate "asylum in Livorno" with the Grand Duke of Tuscany through the mediation of the philosopher Lorenzo Magalotti.

Last years

From 1670 until his death he lived in The Hague. In 1673, Johann Ludwig Fabricius (J. L. Fabritius), professor of Theology, offered him a chair of Philosophy at his University (Heidelberg) by order of the Elector of the Palatinate; Spinoza did not accept it, because, although he was guaranteed "freedom to philosophize", he was required "not to disturb the publicly established religion." The court of justice of the regime that emerged after the murder of Johan de Witt also prohibited, on July 19, 1674, the Theological-Political Treatise (TTP). An attempt of his to publish his Ethics in Amsterdam was thwarted by an unfavorable report submitted to the authority. He then conceived the project of making a Hebrew Grammar , before undertaking a translation of the Old Testament into Dutch, although not even the attempts of that intention have reached the present day, frustrated by death. A year before his death, he was visited by Leibniz, but he denied the meeting.

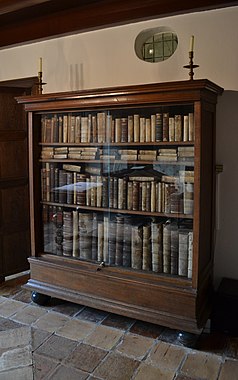

Undermined by tuberculosis, he died on February 21, 1677 at the age of 44. He did not conclude his Political Treatise (TP). An inventory of his possessions made after his death included a bed, a small oak table, a three-legged corner table, and two small tables, his lens-polishing kit, some one hundred and fifty books, and a chess set. In November of that same year, his friends published simultaneously in Latin (Opera posthuma, OP) and in Dutch (Nagelate schriften, NS) all the unpublished works they found, including your correspondence. The book was included in the Vatican's Index librorum prohibitorum in 1679.

Thought

Epistemology

Understanding and imagination

In Spinoza, it is worth saying from the beginning, there is no dualism. That is to say: soul and body are not separate entities, but rather one and the same thing, but seen from different perspectives (E, III, p2, esc.). By hypothesis: if the soul could not think, the body would be inert and vice versa (idem). Soul and body is then the same, only that in the first term it is understood from the attribute of thought and in the second from the extension (idem). Having said this, another issue to highlight right away is that, as each organism perseveres in its being (E, III, p6), it may or may not harm itself. In other words: it can decrease or increase its power to continue to exist and to act (E, IV, p8). What favors him and is useful to him is good. What affects him and hurts him is bad (idem). It remains implicit, but it is worth emphasizing, that this good and this evil are relative for man, since he is the one who judges which things are favorable to him and which are not, and he may prefer between them (E, III, p9, esc.): either craving some or hating others (E, IV, p19, dem.).

Arranged these considerations, it can be said that the problem to consider seriously is that of the possibility of true knowledge. Indeed ―in a very superficial and concise way―, it is assumed or presupposed that both fantasy and intellection (to speak with synonyms from time to time) determine what concerns them, that is, they establish their own limits. Without being excessively rigorous, imagination can be understood as anything other than understanding, and that keeps the soul in a passive or contemplative character (TIE, §84). On the contrary, the understanding leads to the soul being able to act, which is why it gives it a character of activity (E, III, p3, dem.). To this extent, what is useful to us increases our power, which means that it elevates us and frees us in a certain way -leaving aside the finite, for the moment-, since it makes us watch over the eternal rather than the perishable (TAR, §9).

Imagination is referred solely and exclusively to the body (TIE, §84), and it drags us to it with all its passions, for this reason it leads us to suffer. And for this reason, the love that it promotes towards real and singular things brings us closer to death, since they are insecure and uncertain goods by nature (Ibid., §9). His fictions, moreover, are not produced by the subject as such, but arise from external causes that affect the body (Ibid., §84 and §82). Emphasizing, then, that imagination is the opposite of understanding, and that the guiding thread is the possibility and realization of an epistemology, some clarifications are needed:

- Imagination involves having confusing ideas, i.e. knowing partly the things that are a whole (TIE, §63). In other words, if we were wrong, if we were misleading about something, it is because we conceive it abstractly (Ibid., §75), that is, partly, mutilated.

- While Spinoza does it Treaty on the Reform of Understanding (TIE) the distinction between three products of imagination and vague experience (fictitious, false and doubtful ideas), in the Ethics (E) He speaks only of inadequate ideas.

- As soon as anything is more generally conceived, the more you imagine it—it shows confusingly. And as soon as the same thing is more concretely conceived, the more it is understood—it is clearly revealed—" (TIE, §55). General is synonymous with abstract, isolated and even universal, it should be said. At least in the specific context in which issues have been raised.

- From the above, it is further followed that the less the more understood can be fined, and vice versa (Ibid., §58).

- Abstract (universe) notions cannot deduce singular and real things (ibid., §80). So the imagination cannot account for the property of the existing things. The only thing that breeds is confusion, deceit and doubt, and therefore leads to terrible mistakes not distinguishing it from understanding (ibid., §87).

- The abstract and universal interrupts the progress of understanding (ibid., §99). This does not mean, much less, that the imagination is dispenseable or that we should discard it. Fictions or fantasies are also knowledge, but confused, disordered, partial and isolated from their concrete reality. It is the first way of knowing (Ibid., §19), but, if we were to stay with the imagination alone and exclusively, we would not thoroughly know anything.

Understanding, on its own, can be defined negatively. That is, remembering that its opposite is the imagination, which we have just detailed. In this way, it should be immediately clarified that, with your effort, it is possible to have clear and distinct ideas ―as opposed to confused or inadequate― that are formed by the soul ―instead of arising from the movements of the body (TIE, §91)―. Doubt has no place in understanding, it should be noted, because it arises from investigating things without order (Ibid., §80). And this would be another vital difference between imagination and intellection: the first knows partially (as we have already explained), but the second knows concretely, clearly and truly, that is, it knows things by their first causes (Ibid., §70).. And, thus, it is that Spinoza can say that the order of understanding must be in accordance with that of Nature (Ibid., §95 and §99), or, with his words: «the order and connection of ideas is the same as the order and connection of things» (E, II, p7). But if it is not yet explicit why they should be differentiated, let the author himself clarify the relevance of the matter:

When we do not distinguish between imagination and intellect, we think that what we imagine more easily is clearer for us, so we believe to understand what we imagine. Hence, we put forward what needs to be postponed, and thus the true order to advance in knowledge is translated and no correct conclusion is reached.Treaty on the Reform of Understanding (TIE) §90

Ontology

Infinity of substance

Without leaving aside what was said above regarding understanding and imagination, it should be noted that the latter does not stop presenting difficulties to overcome. A clear example of this is how things appear in the imagination: composed of parts, multiple and divisible. While, as conceived by understanding, which corresponds to reality, the same things are: infinite, unique and indivisible.

Everything in the universe is effectively infinite, from an ant to a galaxy. But this needs to be clarified, so that we take into account the meanings that Spinoza handles in relation to said word:

- Infinite by its own nature and definition, because it has no limits. It is only understood, not imagined (Ep., letter 12).

- Infinite evil, which has no limits not by essence, but by external causes. Those whose parts cannot be explained with numbers even though they are limited (dem).

The justification why our author preferred (1) instead of (2) is explained in a simple way when he states that the problem that always arises is that we try to imagine everything. That is to say, that we get involved in seeing things as composed of parts and, therefore, as divisible. In this specific case, the misleading, fictitious and dubious assumption is that of an infinite that is measurable and composed of finite fragments (E, I, prop. 15, esc.). But various absurdities follow from here (idem), so that a first firm conclusion is that (1) cannot be measured and cannot be composed of finite things (idem). Well, although it seems redundant to warn it, (2) is the one that is expressed as a sum of parts. The one that Spinoza prefers, which is (1), is the one conceived by the understanding solely and exclusively, so that it is not imagined (Ep., letter 12).

It would be necessary to know, then, how it is that all things are infinite, even though they have determined existences. And how is it possible that they are unique and indivisible. But these three qualities that the understanding allows us to conceive, can be given in different degrees. For this reason it is vital to make direct reference to that which possesses all the qualities or attributes in the highest degree, that is, God, Nature or substance. The latter is defined as that whose essence necessarily implies its existence, so that it is the cause of itself (E, I, prop. 8, dem.). God is this indeed, but he is best described as an "absolutely infinite being consisting of infinite attributes" (E, I, def. 6).

Now, the explanation regarding why there is only one God and not several, can be summarized taking into account, first of all, that outside of understanding there are only «substances», their attributes and their affections ―modes (E, I, prop. 4) ―, and, secondly, conceiving hypothetically how two or more substances would be distinguished, if they actually existed. In this way, it is intuited that they would be distinguished by their attributes or their affections. If it were the first case, then there would not be two substances that shared the same main quality (E, I, prop. 5), so that they would all be radically different from the others ―like Leibniz's monads―, and the order and connection of reality and of understanding it would not be possible for it to agree; for the latter, despite the progress it is capable of making, is limited. If it were the second case, then all substances would be one; because, remembering the principle of identity of indiscernibles: A = A and A ≠ B... Or, what is the same: as all substances are prior to their affections (idem), what is fundamental about them would be the same in all, and, therefore, several could not be thought of.

The infinity of the substance is proven by Spinoza in two ways: on the one hand, he establishes that the possibility of it existing as finite, but that would require that another substance with its same nature ―same attributes (idem)― serve it limit (E, I, prop. 8, esc. I). This, however, is the first thing that was ruled out by saying that there is only one God. And, on the other, he also explains that an infinite being is "absolute affirmation of the existence of any nature" (idem), so that said being contains in its bosom everything that is necessary for it to have life at some point (E, I, prop. 29).

Indivisibility, also in two ways: its “parts” would preserve infinity or not. If it is the first case, then there would be several substances, but, again, it was the first to be ruled out as absurd (E, I, prop. 13, dem.). If it is the second, it could stop being (idem). Then he adds another distinction: a "part" of a substance would in turn be a finite substance, but that is contradictory to his definition (E, I, prop. 13, esc.).

To answer the question about infinite and determined existences, it would be necessary to add that the attributes of God express his essence (E, I, prop. 19, dem.), and, since eternity belongs to the nature of the substance, its main and fundamental qualities are also (idem). Then, as determined existences are the modes or affections of those attributes, they also share their infinity, indivisibility, and uniqueness, of course, to less perfect degrees.

There is enough to say. Because accepting the infinity of the substance implies, for example, assuming that all that exists are modes of it, that it is an immanent cause, that it has infinite attributes even though we only know it through only two (thought and extension), that it is a cause free and in turn is the most determined being that exists, etc. But all the effects of committing to Spinoza's pantheism are contained or implied in the following quote, which he himself repeats in several sections: "Everything that is, is in God, and without God nothing can be or be conceived» (E, I, prop. 15).

Concept of expression

The erroneous attribution to Einstein of the phrase according to which "everything is relative" is famous, the misinterpretation of which has been the subject of irony due to the absurdities it apparently implies. This from a peculiar sense, of course: that related to the field of logic —where something is recognized as true or false. According to this perspective, that everything is relative would be the same as saying that there are no undeniable or absolute truths, and, therefore, that there is no possible sure or stable knowledge about anything. With which, following the Cartesian idea of the tree or building of knowledge, attacking the fundamentals would collapse everything. So that science and philosophy would not only be useless, but would also be impossible.

If there were no truths that could be known and understood, any discussion or investigation would be doomed to failure. We would be engrossed in a world of opinions, each one trapped in the particular disposition of his brain (E, I, ap.). And the dialogue would be a fiction, since each one would have their own truth that could not be criticized, but only respected by the others; since, as everyone would know and would repeat, "everything is relative, and the truth that the other exposes as his is immeasurable." It is the risk that the sophists pointed out and took since antiquity, who, in another master phrase —of those that show the situation of thought in an era— wonderfully summed it up: “man is the measure of all things”.

Einstein's phrase was not expressed in this sense in which the sophists and Descartes would have imagined it, which is, moreover, the same one that most of the people who know it express and repeat it as an excuse to say anything no matter how absurd. That everything is relative must be understood, simply and simply, as "everything is related or connected", adding the precision that "everything" encompasses what exclusively exists. So, from this other perspective, one speaks of the metaphysical realm: where something is recognized as existing as necessary and as non-existent as impossible (CM, 240/25, chap. III). The matter is not reduced, then, to whether this or that is true or false.

Thus, everything that is real —from a star, a planet or a stone, to any animal or man, and everything that is not yet known but is there—, however hard it is to imagine and understand, is related to each other. Each existent is connected to all the others; the entire universe would be like an immense spider web, where what affects one is also felt by others. To understand this, however, other issues must be exposed: Spinoza, unlike Descartes, did not refer to God as a mere asylum against solipsism, but rather conceived it as the foundation of everything that exists (E, I, p25, esc.). This, it is necessary to clarify immediately, is not about the figure of creator or demiurge that the religious tradition assigns to his deity (E, II, p3, esc.).

The Dutch philosopher was referring, in the first place, to the fact that substance is the only thing that necessarily exists —as far as it is impossible for it to be otherwise— (E, I, p11, dem.) in and of itself, so that it is its own sustenance (E, I, p8, esc. II). That is to say, it does not need anything else —any external cause (E, I, p11, esc.)— to exist, but rather it is self-sufficient (E, I, p7, dem.). It is his own cause, which is called causa sui (E, I, def1). And, in this sense, it is understood that everything that does need an external cause that supports its existence must be based on —or caused by— the substance (E, I, def5). This is identified completely and entirely with God, so that it really is the one who preserves everything that exists (E, I, p15, dem.). But it is not the same as in the religious tradition, because the divinity does not only create what it pleases —that is, it does not choose what possible comes to exist—, but rather everything that is not absurd or impossible exists (E, I, p33, esc. II). This shows his power or power to act (idem).

It goes without saying that, for Spinoza, there was only one substance, and that was God or Nature (E, I, p5, dem.). Everything that exists, then, from stone to man, does not have its being in and of itself. Their existence depends on external causes, and therefore, since they are created things, they depend on the only thing that exists as causa sui. Other than created, then, what distinguishes the things of God? Worth the redundancy in the primordial point: in that we are not substance; we are, in truth, derivatives of it. The Dutch philosopher, to explain himself, distinguishes between the substance, its attributes and its modes. The first is the only thing that has its existence by causa sui (E, I, def3); the second refer to the essential definitions of the substance (E, I, def4); and third parties, to their ways of expressing themselves particularly and determinedly (E, I, def5).

God or substance refer, then, to existence itself, which is eternal and infinite (E, I, p8, esc. II). In this sense, it is absolute and indeterminate, because it can also manifest itself in infinite ways (E, I, p16, dem.). So that divinity cannot be imagined in any way, since that would be limiting it, reducing it, taking away its dignity and legitimacy as the foundation of everything that exists. From all that has been said, it follows in turn that anything created, because it comes from the same causa sui, has something divine in its own constitution. For this reason, each thing is an expression or manifestation of Nature or of God. Nothing is unworthy of its infinity (E, I, p15, esc.) nor of its perfection —of its reality.

Which, with all its letters, would be to differentiate that, although God or the substance can be understood absolutely and indeterminately without referring to the ways that derive from its existence, the truth is that all created things are in God and are conceived by him (E, I, p15, dem.); so that all things, from the ant or the bacterium to man, are divine as expressions of the substance —the way of understanding it particularly and determinedly— (E, II, p7, esc.). Nature, then, is the same everywhere (E, III, pref.).

Soul-body relationship

God, as infinite, possesses in turn infinite attributes or essential definitions (E, I, def6). But it is only understandable to man in terms of only two of them: thought (E, II, p1, dem.) and extension (E, II, p2). And this, taking into account the concept of expression, means that the order and connection of ideas —field of the first attribute— is the same as the order and connection of things —scope of the second— (E, II, p7, cor.), since they are based on the same foundation: Nature or substance. In the same way, the individual in his particularity can understand himself by defining himself through thought, saying, then, that he has a soul; or from extension, saying that he has a body (E, II, p13, cor.). Both are one and the same thing seen in different ways (E, II, p7, esc.).

Before continuing, it should be clarified that every time we have spoken of an individual, we have referred to one made up of several bodies (E, II, p13, post. I esc.). Regarding the latter, the Dutch philosopher clarifies that knowing their nature —field of extension— is that one can distinguish the perfection or reality of the different ideas that are the concepts of each one of them —field of thought— (E, II, p13, sc.). Focusing, then, on bodies —which imply a single divine attribute: extension— he clarifies that they are distinguished from each other by their movement or rest, and not by their substance (Ibid., lemma I), since God or Nature it is the only one that exists properly speaking. If there were more than one substance, it would have to be produced by something else, which is absurd (E, I, p6, cor.) by its very definition as causa sui.

Continuing with the idea of a compound individual, Spinoza considered that several bodies could be grouped as they moved one to the other according to a certain relationship (E, II, p13, esc. def.). In addition, this union of bodies would retain its nature even if the bodies that compose it changed, because what is relevant is the relationship of movement and rest that has been established from the beginning (Ibid., lemma IV). The compound, then, can be affected and change in infinite ways, always preserving its nature (Ibid., lemma VII). This is understandable if it is remembered that bodies, like ideas, are above all modifications of the substance, but they are not itself (E, I, p8, esc. II). So, again, "all nature is a single individual, whose parts—all bodies—vary in infinite ways, without any change in the total individual" (E, II, p13, lemma VII, esc). One can now see why specifying what being a composite individual entailed.

The idea of the human soul, for its part, implies the existence of a body (E, II, p13, dem.). If it also refers to something else, an effect should be produced and the idea associated with it revealed. But, since this is not the case, it can be said that the soul has a body as its object (idem), and, in the case of man, it not only possesses it but also exists as it feels (E, II, p13, cor.). But soul and body, since they are one and the same thing, are not two empires trying to conquer each other. It is simply and simply impossible for them to influence each other, since each one refers to different attributes of the substance. Just as in the case of bodies nothing leads them to move or remain at rest but the influence of other bodies —other modes of extension— (Ibid., lemma III, cor.), nothing can lead the soul to think but other modes of thought (E, III, p2, dem.).

This does not mean, however, that body and soul are separate from each other and are independent of each other. Both are the same thing expressed in different ways: the object and its definition (E, II, p13, dem.). In this way, it can be recognized that the order of the actions and passions of the body is the same as that of the actions and passions of the soul (E, III, p2, esc.). If one insisted on continuing to analyze the matter —that is, on separating what is united—, the intimate identification between the mode of thought with the mode of extension could be shown, bringing up those who defend that, if the soul is inept at thinking, then the body would not move (idem). They believe that they thus demonstrate a dominance of the first over the second; but it is convenient to reverse the argument to explain that, in the same way, if the body did not move, the soul could not think (idem). To say it with all the letters: it is not possible that there is a human body without a soul or a human soul without a body.

And if it were still not clear that the soul does not dominate the body or vice versa, with Spinoza we would have to remember that «nobody has determined what the body can» ―what can be deduced from its nature ― (idem), so that they cannot explain all its functions, and this is confirmed in that the same «can do many things that are astonishing to its own soul» (idem). This without mentioning what is implicit behind what has been said up to now: since everything is in God and is conceived by him (E, I, p15, dem.), it follows that everything necessarily exists (E, I, p33, esc. II). So that the actions and passions of man follow a strict, inevitable and inviolable order, and for this reason the Dutch philosopher can treat them as if it were "a question of lines, surfaces or bodies" (E, III, pref.). Those who insist on considering themselves free do so because they are aware of their actions and because they do not take into account the causes that determine them (E, III, p2, esc.). What Jorge Luis Borges expressed precisely when he said: "our ignorance of the complex machinery of causality" (Nine Dantesque essays). Thus, what we call "decision" in the field of thought is a "determination" in the field of extension (E, III, p2, esc.). Spinoza, once again, makes us face reality as it is:

those who believe that they speak, or silence, or do anything, for free decision of the soul, dream with eyes openEthics demonstrated according to geometric order (E), III, p2, esc.

Conatus

The conatus is a central theme in the philosophy of Benedicto Spinoza. According to him: "Every thing strives, as much as it can, to persevere in its being" [Unaquaeque res, quantum in se est, in suo esse perseverare conatur] (E, III, p6). Spinoza presents some reasons to believe this. First, particular things are modes of God, which means that each expresses the power of God in a particular way (E, III, p6, dem.). Furthermore, it could never be part of God's definition that his ways contradict each other (E, III, p5); each thing, therefore, "opposes everything that can take away its existence" (E, III, p6, dem.). Spinoza formulates this resistance to destruction in terms of an effort to continue to exist, and conatus is the word he uses most often to describe this force.

Strive to persevere is not simply something one thing does, in addition to other activities that might happen. Rather, the effort is "nothing more than the real essence of the thing" (E, III, p7). Spinoza also uses the term conatus to refer to rudimentary concepts of inertia, as Descartes had done earlier. Since a thing cannot be destroyed without the action of external forces, motion and rest can also be destroyed. exist indefinitely until disturbed.

Man could also be defined by the conatus. Referred to the soul is will (voluntas); but, when he refers to the soul and the body at the same time, he calls it appetite ( appetitus ). On the other hand, desire (cupiditas) is "the appetite accompanied by self-awareness" (E, III, p9.); which is, one could say, the essence of man "as soon as it is conceived as determined to do something by virtue of any affection that occurs in it" (E, III, def. affect.). Desire is the idea that We have appetite, which when we are aware of the decrease in our power to act, our conatus, produces the affect (afectum ) of sadness. On the other hand, joy "is a passion through which the soul passes to a greater perfection" (E, III, p11.) when we are aware of the increase in our power.

Causality

Although the Principle of Sufficient Reason is most commonly associated with Gottfried Leibniz, it is arguably found in its strongest form in Spinoza's philosophy. Within the context of Spinoza's philosophical system, the principle can be understood to unify causation and explanation. What this means is that for Spinoza, questions about the reason why a given phenomenon is the way it is (or exists) can always be answered, and can always be answered in terms of the relevant cause(s). This constitutes a rejection of teleology or final causation, except possibly in a more restricted sense for human beings. Given this, Spinoza's views regarding causation and modality begin to make a lot more sense.

Spinoza has also been described as an "Epicurean materialist," specifically in reference to his opposition to Cartesian mind-body dualism. This view was held by the Epicureans before him, as they believed that atoms with their probabilistic paths were the only fundamentally existing substance. Spinoza, however, deviated significantly from the Epicureans by adhering to strict determinism, as than the Stoics before him, in contrast to the Epicurean belief in the probabilistic path of atoms, which is more in line with contemporary thinking on quantum mechanics.

Emotions

One thing that seems, on the surface, to distinguish Spinoza's view of emotions from Descartes' and Hume's descriptions is that he considers emotions to be cognitive in some important respect. Jonathan Bennett states that "Spinoza saw emotions primarily as caused by cognitions. However, Spinoza did not say this clearly enough, and sometimes lost sight of it altogether." Spinoza provides several demonstrations that purport to show truths about how human emotions work. The picture presented is, according to Bennett, "unflattering, tinged as it is with universal egoism".

Ethics

Spinoza's notion of beatitude occupies a central place in his ethical philosophy. Beatitude (or salvation or freedom), Spinoza thinks:

consists of a constant and eternal love of God, or in the love of God for men. (E, V, p36)

And this means, as Jonathan Bennett explains, that "Spinoza wants 'beatitude' represents the highest and most desirable state one could be in'. Here, understanding what 'the highest and most desirable state' means requires understanding Spinoza's notion of conatus (read: strive, but not necessarily with any teleological baggage) and that "perfection" It does not refer to (moral) value, but to completeness. Since individuals are identified as mere modifications of infinite Substance, it follows that no individual can ever be fully complete, that is, perfect, or blessed. Absolute perfection is, as noted above, reserved solely for Substance. However, the mere modes can achieve a lesser form of bliss, viz., that of pure understanding of oneself as one really is, that is, as a definite modification of Substance in a certain set of relations to all things. others in the universe. That this is what Spinoza has in mind can be seen at the end of the Ethics, in E, V, p24 and E, V, p25, where Spinoza makes two final key moves, unifying the metaphysical propositions., epistemological and ethical that has been developed throughout the work. In E, V, p24 he links the understanding of particular things to the understanding of God, or Substance; in E, V, p25, the conatus of the mind is linked to the third type of knowledge (intuition). From here, it is a small step to the connection of the Beatitude with the amor dei intellectualis ("intellectual love of God").

Politics

On the political side, Spinoza partly follows Thomas Hobbes. However, his doctrine had a great influence on the thought of the 18th century, since he is considered the initiator of atheism, although this statement is not entirely correct.

As a philosopher, he shares the theme of determinism with Hobbes. However, Spinoza was always, and in all fields, an outlawed writer, to the point that at the beginning of the 19th century he was not recognized, especially by the German romantic movement (Goethe, Jacobi, etc.).

Within the realm of politics, he is considered the forerunner of Jean-Jacques Rousseau.

His thought translates the worldview of Galileo, who maintains that the world is subject to certain laws, so he will look for those that regulate society. On this point he partly agrees with Descartes and Hobbes, but with the singularity that Spinoza also seeks the laws that govern morality and religion. Thus, he introduces both morality and religion, trying to introduce reason in both spheres, for which he uses a rational method.

In his Ethics demonstrated according to the geometric order, Spinoza speaks of God, of the human being and of the place that man occupies within nature. For him, the correct way to understand men is as one more part of nature, and human actions should not be analyzed with moral criteria, but as necessary parts of the laws that govern the cosmos; that is, there are universal laws of nature to which men are subject, so it cannot be said that man is totally free. Following this approach is one of the most important statements of his and that brought him the most problems, namely: values are arbitrary human creations.

On the political issue, the philosopher claims the broadest possible democracy, although within this he does not explicitly include women, to whom he asks whether or not they should have political rights, which is not very clear to him; he finally leans towards sustaining an innate inferiority of women, and affirms that the best government belongs to men. However, he leaves a door open for recognition by women, finally saying that they are equal to men, that they can govern, but that it is best to avoid the subject, since it can generate conflicts.

According to his political thought, the purpose of the State is to make all men free, which means that man should not be an automaton.

Reception

Pantheist, panentheist or atheist?

Shortly after his death in 1677, Spinoza's works were placed on the Catholic Church's Index librorum prohibitorum. Other condemnations soon followed, such as that of Aubert de Versé in his work L'Impie convaincu, ou Dissertation contre Spinoza (1685). According to his subtitle, in the work “the foundations of [Spinoza's] atheism are refuted.” Johann Franz Buddeus called him “the atheorum nostra aetate princeps” (the great prince of atheists of our times). Pierre Bayle in his Dictionnaire historique et critique claimed that Spinoza was the first systematic atheist: «Il a été un athée de systeme, et d'une méthode toute nouvelle, quoique le fond de sa doctrine lui fût commun avec plusieurs autres philosophes anciens et modernes, européens et orientaux".

It is commonly believed that Spinoza equated God with the material world. As a consequence, the philosopher has been considered among the greatest exponents of pantheism. But, in a letter addressed to Henry Oldenburg, he states: "As for certain people who assume that I identify God and Nature (by which they understand a certain mass or corporeal matter) as one and the same thing, they are totally wrong" (Ep 73). For Spinoza, each individual knows the Universe through the attributes of thought and extension (E, II, p1-2), following the order and connection of ideas, which is the same in things (E, II, p7). From the essence of God (E, I, p20, dem.), on the other hand, an infinity of other attributes and modes follow (E, I, p16, dem.), but the human understanding can only encompass them in a "partial and inadequate" (E, II, p11, cor.).

According to the German philosopher Karl Jaspers (1883-1969), when Spinoza wrote Deus sive natura ("God or Nature"), he implied that God is natura naturans (creative nature), and not natura naturata (created nature). He also defended about this philosophical system that God and Nature are not interchangeable terms, but that the transcendence of the divine essence is expressed in the infinity of its attributes, and that the two attributes known to humans —thought and extension— they express the immanence of God. But, from the perspective of the German philosopher, even limited to the attributes just mentioned, God cannot be strictly identified with our world. According to Jaspers, the pantheistic motto "one and all" would be valid for Spinoza only if "one" maintained its transcendence and "all" was interpreted as the totality of finite things.

Martial Guéroult (1891-1976) suggested that the term "panentheism" might better describe Spinoza's view of the relationship between God and the world than "pantheism." The world is not God, but it is, in a quite definite sense, in God. Not only do all finite things have their cause in God: they cannot even be conceived without God. However, the American panentheist philosopher Charles Hartshorne (1897-2000) insisted that Spinoza's view would be better described by the term "classical pantheism".

In 1785, Friedrich Heinrich Jacobi published a condemnation of Spinoza's pantheism, after word spread that Gotthold Lessing had confessed before he died to being a "Spinozian"—understood at the time as a synonym for "atheist"—. Jacobi claimed that Spinoza's doctrine was pure materialism, because he declared that Nature and God are nothing more than extension. This, according to Jacobi, was the result of typical Enlightenment rationalism and could only lead to absolute atheism. Moses Mendelssohn disagreed with this interpretation, stating that there is no real difference between theism and pantheism. This issue became one of the greatest intellectual and religious debates in European civilization at the time.

For Europeans in the second half of the 18th century century, Spinoza's philosophy was particularly attractive because it provided an alternative to materialism, atheism and theism. There were three of Spinoza's ideas that most attracted them:

- the unity of all existing;

- the order and connection of everything that happens;

- and the identity between the soul and God.

In 1879 there were those who praised Spinoza's pantheism; however, others still considered it alarming and dangerous. Spinoza's words referring to "God or Nature" (Deus sive Natura) suggested a living, natural deity, in contrast to the "first cause". » by Isaac Newton and the mechanistic materialism of Julien Offray de La Mettrie (1709-1751) in his work The machine man (L'homme machine). Coleridge and Shelley saw in Spinoza's philosophy a religion of Nature, and Novalis called him "the God-intoxicated man". Shelley was inspired by Spinoza to write his essay The necessity of atheism.

Spinoza was considered an atheist because he did not speak of God in the same way that the Judeo-Christian monotheistic tradition did. As Frank Thilly expresses in his interpretation: «[…] he clearly denies that God can have personality or consciousness; He […] he has neither intelligence, nor sensitivity, nor will; He does not act according to ends, but everything necessarily results from his nature, according to the law [...]". Therefore, Spinoza's distant and indifferent God is the antithesis of the concept of an anthropomorphic and paternal God who is interested in the fate of humanity.

According to the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Spinoza's God is an "infinite intellect" (E, II, p11, cor.), omniscient (E, II, p3) and capable of appreciating men to the extent that he loves himself (E, V, p36, cor.). It is in this sense that Spinoza exposes divine intellectual love ―amor intellectualis Dei― as the supreme good for men (E, V, p20, dem.), insofar as the “more we know the singular things, the more we know God" (E, V, p24). Which consequently implies that, the closer human understanding approaches to deity, it reaches an "adequate knowledge of the essence of things" (E, V, p25, dem.) ―totally opposed to inadequate and partial (E, II, p11, cor.)―.

However, the issue is complex. Spinoza's God does not have free will (E, I, p32, cor. 1), he has no objectives or intentions (E, I, app.). On the other hand, the philosopher emphasizes that "if understanding and will belong to the eternal essence of God, then [they must be] something different from what men ordinarily understand" (E, I, p17, esc.).

Steven Nadler, interpreter of the author of Ethics (E), suggests that the answer to the dilemma of the alleged atheism attributed to Spinoza depends on the definition that is taken as the starting point for the discussion. If pantheism is associated with religiosity, then the Dutch philosopher is not. Since, according to this same thinker, our attitude towards God should not be the religious disposition to take refuge in his will ―“that asylum of ignorance” (E, I, ap.)―, but, for on the contrary, the objective and rational philosophical study; that is, the love for knowledge, since "ignorance suppressed, stupid admiration is suppressed" (idem). The religious inclination leads to live under the fluctuation between hope and fear (E, III, p50, esc.), in the face of fortune, which in turn leads to superstition and the ruin of man as long as it "[disguises ], under the specious name of religion, the fear with which they want to be controlled, so that [they fight] for their slavery, as if it were their salvation" (TTP, pref.).

Comparison with Eastern philosophical traditions

Several authors have discussed the resemblance between Spinoza's thought and Eastern philosophical traditions. The Sanskrit scholar Theodor Goldstücker was one of the first, in the 19th century, to underline the similarities between Spinoza's thought and the traditional Indian school Vedanta. Goldstücker wrote that:

[...] a Western philosophical system that occupies a fundamental place between the philosophies of all times and nations, and that is [to that extent] such an exact representation of the ideas of the Indian classical thinking school Vedanta that we could suspect that his author had copied his fundamental principles of the Hindus, if his biography did not assure us of his total ignorance of his doctrines.

I am talking about the philosophy of Spinoza, a man whose own life is a representation of that moral purity and indifference to the transient charms of this world, an attitude that is the constant affinity of the true philosopher Vedanta [...].

Compared to the main ideas of both systems, we should not find any difficulty in demonstrating that, if Spinoza had been Hindu, his system would certainly have marked a final phase of Vedanta philosophy.

In his lectures, Max Müller underlined the striking similarities between Vedanta and the Dutch philosopher's system, saying that "Brahman, [as] conceived in the Upanishads and defined by Sankara, is clearly the same as Spinoza's "substance". Helena Blavatsky, founder of the Theosophical Society, also compared Spinoza's philosophical thought to Vedanta, writing in an unfinished essay: "[...] God ―natura naturans― understood [simple] and only with its attributes; and God himself ―as natura naturata― understood as the infinite series of modifications and relationships, the direct flow that results from the properties of those same attributes. That is exactly Vedanta divinity."

The interpretation of Spinoza in the 19th and 20th centuries

In the Europe of the 19th centuries and xx interest in Spinoza grew, often from a left-wing or Marxist perspective. Karl Marx appreciated Spinoza's "world view" (Weltanschauung), interpreting it as materialist. Friedrich Engels wrote that "it is a great honor for the philosophy of that age [...] that it insisted, from Spinoza to the great French materialists, in explaining the world by itself, leaving to the science of nature of the future the care of offering detailed justifications".

Louis Althusser, Gilles Deleuze, Antonio Negri and Étienne Balibar ―among other authors― have been inspired by Spinoza's philosophy. Deleuze's doctoral thesis, published in 1968, calls him "the prince of philosophers". Nietzsche had few philosophers in his esteem, and Spinoza was among them. However, he never read their works directly, instead learning about him in History of Modern Philosophy, by Kuno Fischer.

The philosopher Jorge Santayana published an essay entitled "Spinoza's ethical doctrine" in the literary magazine The Harvard Monthly, after graduating from the same university. Later, he wrote an introduction to a edition of the Ethics (E) and the Treatise on the reform of understanding (TIE). In 1932, Santayana was invited to present an essay ―finally published under the title of "Ultimate Religion"—at a gathering held in The Hague to celebrate the tercentenary of Spinoza's birth. In his autobiography, Santayana described Spinoza as his "exemplary teacher and model" in understanding the naturalistic foundation of religion. morality.

Work

| Latin title | Title translated | Abbreviation used when quoting the work | Year(s) of writing | Year of publication | With the consent of the author | Edition

póstuma | Attribution

Dudosa | Completed by the author in life |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Renati Descartes principia philosophiae, more geometrico demonstrata | Principles of Descartes philosophy demonstrated according to geometric method | PPC Principia philosophiae cartesianae | - | 1663 | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Cogitata metaphysica | Metaphysical thinking | CM | ||||||

| Tractatus theologico-politicus | Theological-political Treaty | TTP | - | 1670 | ||||

| Tractatus de intellectus emendatione | Treaty on the Reform of Understanding | TIE | 1661 | 1677 | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Ethica, ordine geometric demonstrata | Ethics demonstrated according to geometric order | E | 1661-1675 | ✔ | ✔ | |||

| Tractatus politicus | Political Treaty | TP | 1675-1677 | ✔ | ||||

| Epistolae | Correspondence | Ep | 1661-1676 | ✔ | ✔ | |||

| Compendium grammatices linguae hebraeae | Hebrew grammar compound | Compendium | - | ✔ | ||||

| Tractatus de Deo et homine ejusque congratulatete | Short Treaty | KV Korte Verhandeling | 1660-61 | 1862 | ✔ | ✔ | ||

| Reeckening van de Regenbogen (Dutch) | Algebraic figure of the rainbow | - | - | 1687 | ✔ | ✔ | - | |

| Reeckening van de Kanssen (Dutch) | Probation calculation | - | - | ✔ | ✔ | - |

Correspondence

Spinoza corresponded from December 1664 to June 1665 with Willem van Blijenbergh, an amateur Calvinist theologian, who questioned Spinoza on the definition of evil. Later, in 1665, Spinoza notified Henry Oldenburg that he had begun work on a new book, the Theological-Political Treatise, published in 1670. Leibniz strongly disagreed with Spinoza on his own manuscript "Refutation of Spinoza", but he is also known to have met Spinoza on at least one occasion (as mentioned above), and his own work bears some striking similarities to specific important parts of Spinoza's philosophy (see: Monadology).

In a letter, written in December 1675 and sent to Albert Burgh, who wanted to defend Catholicism, Spinoza clearly explained his view of both Catholicism and Islam. He claimed that both religions are made “to deceive people and constrict the minds of men.” He also claims that Islam far surpasses Catholicism in doing so. The Tractatus de Deo, Homine, ejusque Felicitate (Treatise on God, Man and His Happiness) was one of Spinoza's last published works, between 1851 and 1862.

Spanish translations

| Year | Book translated | Translator/editor(s) | Editorial | City | ISBN | Notes on the edition |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1966 | Complete works | Juan B. Bergura | Iberians and L.C.L. | Madrid | 978-84-7083-011-2 | Translation, notes and preliminary study. |

| 2011 | Luciano Espinosa | Gredos | Madrid | 978-84-24919-41-2 | ||

| 2015 | Atilano Domínguez | Live Book | Madrid | 978-84-16423-68-2 | The complete works of Baruch by Spinoza, including his epistolary and the biographies that were composed of him. It does not contain the Compendium of grammar of the Hebrew language. | |

| 1958 | E | Vidal Peña | Partnership | Madrid | 84-206-0243-4 | |

| 1987 | Atilano Domínguez | Trotta | Madrid | 978-84-9879-070-2 | ||

| 2009 | Oscar Cohan | FCE | Mexico City. | 978-96-81604-97-4 | ||

| 2011 | Vidal Peña | Trotta | Mexico City. | 978-84-20654-97-3 | ||

| 2020 | Pedro Lomba | Trotta | Madrid | 978-84-9879-784-8 | Bilingual edition. | |

| 1986 | TTP | Atilano Domínguez | Partnership | Madrid | 84-206-0185-3 | Translation, introduction, analytical index and notes. |

| TP | 84-206-0219-1 | |||||

| 1989 | Humberto Giannini and Maria Isabel Flisfisch. | University | Santiago de Chile | Introduction, translation, notes, índex latinus translationis and bibliography. | ||

| 1988 | TIE, PPC and CM | Atilano Domínguez | Partnership | Madrid | 84-206-0325-2 | Introduction, translation and notes of three works by Spinoza in one volume. |

| 2008 | TIE | Boris Eremiev, Luis Placencia | Colihue SRL | Buenos Aires | 978-950-563-048-6 | Bilingual edition: Latin-Spanish. Notes and preliminary study. |

| 2006 | Oscar Cohan | Cactus | Buenos Aires | 978-98-72100-03-2 | ||

| 1968 | José Francisco Soriano Gamazo | University of Zulia | Maracaibo | Bilingual edition: Latin-Spanish. | ||

| 1990 | KV | Atilano Domínguez | Partnership | Madrid | 84-206-0478-X | Translation, prologue and notes. |

| 2005 | Compendium | Guadalupe González Diéguez | Trotta | Madrid | 978-84-81647-51-8 | |

| 2007 | Ep | Oscar Cohan, Diego Tatián, Javier Blanco | Colihue SRL | Buenos Aires | 978-950-563-041-7 | |

| 1988 | Atilano Domínguez | Partnership | Madrid | 84-206-0305-8 | Translation, introduction, notes and indexes. | |

| Juan Domingo Sánchez Estop | Hyperion | Madrid | 84-751-7236-9 |

Covers of their first editions

Contenido relacionado

Leonardo Boff

Maimonides

Johann Caspar Lavater

Albert Schweitzer

Erasmus of Rotterdam

![Tratado de la reforma del entendimiento (TIE)[n. 3].](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/0b/Tractatus_de_Intellectus.png/120px-Tractatus_de_Intellectus.png)