Baroque

The Baroque was a period of history in Western culture originated by a new way of conceiving art (the «Baroque style») and which, starting from different historical-cultural contexts, produced works in numerous artistic fields: literature, architecture, sculpture, painting, music, opera, dance, theater, etc. It manifested itself mainly in Western Europe, although due to colonialism it also occurred in numerous colonies of the European powers, mainly in Latin America. Chronologically, it spanned the entire 17th century and early XVIII, with more or less extension in time depending on each country. It is usually placed between Mannerism and Rococo, at a time characterized by strong religious disputes between Catholic and Protestant countries, as well as marked political differences between absolutist and parliamentary States, where an incipient bourgeoisie began to lay the foundations of capitalism.

As an artistic style, the Baroque arose at the beginning of the XVII century (according to other authors at the end of the XVI) in Italy —a period also known in this country as Seicento—, from where it spread to most of of Europe. For a long time (XVIII and XIX) the term «baroque» had a pejorative meaning, with the meaning of ornate, deceitful, capricious, until it was later revalued at the end of the century XIX by Jacob Burckhardt and, in the XX, by Benedetto Croce and Eugenio d& #39;Ors. Some historians divide the Baroque into three periods: "primitive" (1580-1630), "mature" or "full" (1630-1680) and "late" (1680-1750).

Although it is usually understood as a specific artistic period, aesthetically the term "baroque" also indicates any artistic style opposed to classicism, a concept introduced by Heinrich Wölfflin in 1915. Thus, the term "baroque" can be used both as a noun as adjective. According to this approach, any artistic style goes through three phases: archaic, classical and baroque. Examples of Baroque phases would be Hellenistic art, Gothic art, Romanticism or Modernism.

Art became more refined and ornate, with the survival of a certain classicist rationalism but adopting more dynamic and effective forms and a taste for the surprising and anecdotal, for optical illusions and dramatic blows. There is a preponderance of realistic representation: in a time of economic hardship, man faces reality more harshly. On the other hand, this harsh reality is often subjected to the mentality of a troubled and disillusioned age, which manifests itself in a certain distortion of forms, in forced and violent effects, strong contrasts of light and shadow, and a certain tendency to imbalance. and exaggeration.

The abuse of the ornamental, the overloading in art is also known as baroque style.

General aspects

Baroque: a polysemic concept

The term «barroque» comes from a word of Portuguese origin (barrôco), whose feminine name denominated pearls that had irregular shapes (as in Spanish the word «barruecas»). It arose in the context of music criticism: in 1750, the French essayist Noël-Antoine Pluche compared the way of playing of two violinists, one more serene and the other more extravagant, commenting on the latter that "he tries at all costs to surprise, to attract attention, with wild and extravagant sounds. It only seems that in this way it was a question of diving to the bottom of the seas to extract baroque [baroc in French] with great effort, while on dry land it would be possible to find valuable jewels much more easily».

"Baroque" was originally a derogatory word designating a capricious, bombastic, excessively ornate type of art. This is how it first appeared in the Dictionnaire de Trévoux (1771), which defines " in painting, a picture or a figure of baroque taste, where the rules and proportions are not respected and everything is represented following the whim of the artist".

Another theory derives it from the noun baroque, a syllogism of Aristotelian origin from medieval scholastic philosophy, which points to an ambiguity that, based on a weak logical content, confuses what is true with what is false. Thus, this figure indicates a type of pedantic and artificial reasoning, generally in a sarcastic tone and not without controversy. In this sense, Francesco Milizia applied it in his Dizionario delle belle arti del disegno (1797), where he stated that “baroque is the superlative of bizarre, the excess of the ridiculous”.

The term «baroque» was used from the 18th century in a derogatory sense, to underline the excess of emphasis and abundance of ornamentation, unlike the clearer and more sober rationality of the Enlightenment. At that time, baroque was synonymous with other adjectives such as "absurd" or "grotesque". Enlightenment thinkers saw in the artistic achievements of the previous century a manipulation of classicist precepts, so close to their rationalist concept of reality, therefore that his criticisms of 16th century art turned the term “baroque” into a pejorative concept: in his Dictionnaire d'Architecture (1792), Antoine Chrysostome Quatremère de Quincy defines the baroque as “a shade of the extravagant. It is, if you will, its refinement or if one could say, its abuse. What severity is to the wisdom of taste, the baroque is to the strange, that is, it is its superlative. The idea of baroque entails that of ridicule taken to excess".

However, art historiography subsequently tended to revalue the concept of the baroque and value it for its intrinsic qualities, while beginning to treat the Baroque as a specific period in the history of Western culture. The first to reject the negative meaning of the Baroque was Jacob Burckhardt (Cicerone, 1855), stating that "Baroque architecture speaks the same language as the Renaissance, but in a degenerate dialect". Although it was not a laudatory statement, it paved the way for more objective studies, such as those elaborated by Cornelius Gurlitt (Geschichte des Barockstils in Italien, 1887), August Schmarsow (Barock und Rokoko, 1897), Alois Riegl (Die Entstehung der Barockkunst in Rom, 1908) and Wilhelm Pinder (Deutscher Barock, 1912), which culminated in the work of Heinrich Wölfflin (Renaissance und Barock, 1888; Kunstgeschichtliche Grundbegriffe, 1915), the first to give the Baroque its own and differentiated stylistic autonomy, pointing out its properties and stylistic features in a revalued way. Subsequently, Benedetto Croce (Saggi sulla letteratura italiana del Seicento, 1911) carried out a historicist study of the Baroque, framing it in its socio-historical and cultural context, and trying not to make any kind of value judgments. However, in Storia dell'età barocca in Italia (1929) he again gave a negative character to the Baroque, which he described as "decadent", just at a time when numerous treatises appeared that claimed the artistic value of the period, such as Der Barock als Kunst der Gegenreformation (1921), by Werner Weisbach, Österreichische Barockarchitektur (1930) by Hans Sedlmayr or Art religieux after the Council of Trente (1932), by Émile Mâle.

Subsequent studies have definitively established the current concept of the Baroque, with small exceptions, such as the differentiation made by some historians between «baroque» and «baroque style», the first being the classical, pure and primitive phase of the art of the century XVII, and the second a mannered, ornate and exaggerated phase, which would converge with Rococo —to the same extent as mannerism it would be the mannered phase of the Renaissance. In this sense, Wilhelm Pinder (Das Problem der Generation in der Kunstgeschichte, 1926) argues that these «generational» styles follow one another based on the formulation and subsequent distortion of certain cultural ideals: as well as Mannerism played with the classical forms of a Renaissance of a humanist and classicist nature, Baroqueism is the reformulation in a formalist key of the Baroque ideological substrate, based mainly on absolutism and counter-reformism.

On the other hand, compared to the Baroque as a certain period in the history of culture, at the beginning of the XX century a second meaning arose, that of "the baroque" as a phase present in the evolution of all artistic styles. Nietzsche already asserted that "the baroque style arises every time great art dies". The first to give meaning Transhistorical aesthetic to the Baroque was Heinrich Wölfflin (Kunstgeschichtliche Grundbegriffe, 1915), who established a general principle of alternation between classicism and baroque, which governs the evolution of artistic styles.

The baton was picked up by Eugenio d'Ors (Lo barroco, 1936), who defined it as an "aeon", a transhistorical form of art ("lo baroque" as opposed to "the baroque" as a period), a recurring modality throughout the history of art as an opposition to the classical. If classicism is a rational, masculine, Apollonian art, the baroque is irrational, feminine, Dionysian. For d'Ors, "both aspirations [classicism and baroque style] complement each other. There is a style of economy and reason, and another musical and abundant. One is attracted to the stable and heavy forms, and the other to the rounded and rising ones. From one to the other there is neither decadence nor degeneration. These are two forms of eternal sensibility."

Historical and cultural context

The 17th century was generally a time of economic depression, the consequence of the prolonged expansion of the previous century caused mainly by for the discovery of America. Poor harvests led to an increase in the price of wheat and other basic products, with subsequent famines. Trade stagnated, especially in the Mediterranean area, and only flourished in England and the Netherlands thanks to trade with the East and the creation of large commercial companies, which laid the foundations of capitalism and the rise of the bourgeoisie. The poor economic situation was aggravated by the plague plagues that ravaged Europe in the mid-XVII century, which particularly affected the area Mediterranean. Another factor that generated misery and poverty were the wars, caused mostly by the confrontation between Catholics and Protestants, as is the case of the Thirty Years' War (1618-1648). All these factors caused a serious impoverishment of the population; in many countries, the number of poor and beggars reached a quarter of the population.

On the other hand, the hegemonic power in Europe shifted from imperial Spain to absolutist France, which after the Peace of Westphalia (1648) and the Peace of the Pyrenees (1659) consolidated itself as the most powerful state on the continent, virtually undisputed until the rise of England in the 18th century. Thus, the France of the Luises and papal Rome were the main nuclei of baroque culture, as centers of political and religious power —respectively— and disseminating centers of absolutism and counter-reformation. Spain, although in political and economic decline, nevertheless had a splendid cultural period —the so-called Golden Age— which, although marked by its religious aspect of incontrovertible Counter-Reformation proselytism, had a marked popular component, and led both to literature and to plastic arts at levels of high quality. In the rest of the countries where the Baroque culture arrived (England, Germany, the Netherlands), its implementation was irregular and with different stamps characterized by their distinctive national characteristics.

The Baroque was forged in Italy, mainly in the papal seat, Rome, where art was used as a propaganda medium for the dissemination of Counter-Reformation doctrine. The Protestant Reformation plunged the Catholic Church into a deep crisis during the first half of the XVI century, which evidenced both corruption in numerous ecclesiastical strata and the need for a renewal of the message and the Catholic work, as well as a greater approach to the faithful. The Council of Trent (1545-1563) was held to counter the advance of Protestantism and consolidate Catholic worship in the countries where it still prevailed, laying the foundations of Catholic dogma (sacramental priesthood, celibacy, worship of the Virgin and the saints, use liturgical Latin) and creating new instruments of communication and expansion of the Catholic faith, placing special emphasis on education, preaching and dissemination of the Catholic message, which acquired a strong propaganda stamp - for which the Congregation for the Propagation of of faith-. This ideology was embodied in the recently founded Society of Jesus, which through preaching and teaching had a notable and rapid diffusion throughout the world, stopping the advance of Protestantism and recovering numerous territories for the Catholic faith (Austria, Bavaria, Switzerland, Flanders, Poland). Another effect of the Counter-Reformation was the consolidation of the figure of the Pope, whose power was strengthened, and which resulted in an ambitious program for the expansion and urban renewal of Rome, especially its churches, with special emphasis on the Basilica of Saint Peter and its surroundings. The Church was the largest artistic patron of the time, and used art as the workhorse of religious propaganda, as it was an easily accessible and intelligible popular medium. Art was used as a vehicle of expression ad maiorem Dei et Ecclesiae gloriam, and popes such as Sixtus V, Clement VIII, Paul V, Gregory XV, Urban VIII, Innocent X and Alexander VII became great patrons and promoted great improvements and constructions in the eternal city, already qualified at that time as Roma triumphans, caput mundi ("Rome triumphant, head of the world").

Culturally, the Baroque was a time of great scientific advances: William Harvey tested the circulation of the blood; Galileo Galilei perfected the telescope and strengthened the heliocentric theory established the previous century by Copernicus and Kepler; Isaac Newton formulated the theory of universal gravitation; Evangelista Torricelli invented the barometer. Francis Bacon established with his Novum organum the experimental method as the basis of scientific research, laying the foundations of empiricism. For his part, René Descartes led philosophy towards rationalism, with his famous "I think, therefore I am".

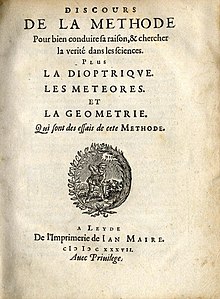

Due to the new heliocentric theories and the consequent loss of the anthropocentric sentiment typical of Renaissance man, Baroque man lost faith in order and reason, in harmony and proportion; Nature, not regulated or ordered, but free and fickle, mysterious and unfathomable, became a more convenient direct source of inspiration for the baroque mentality. Losing faith in the truth, everything becomes apparent and illusory (Calderón: Life is a dream); nothing is revealed anymore, so everything must be investigated and experienced. Descartes turned doubt into the starting point of his philosophical system: «considering that all the thoughts that come to us while awake can also occur to us during sleep, without any then being true, I resolved to pretend that all the things that had hitherto entered in my spirit, they were no more true than the illusions of my dreams" (Discourse on the method, 1637). Thus, while science limited itself to the search for truth, art headed towards the expression of the imaginary, of the longing for the infinite that baroque man yearned for. Hence the taste for optical effects and illusory games, for ephemeral constructions and the value of the transitory; or the taste for the suggestive and seductive in poetry, for the wonderful, sensual and evocative, for the linguistic and syntactic effects, for the strength of the image and the power of rhetoric, revitalized by the claim of authors such as Aristotle or Cicero.

Baroque culture was, in the definition of José Antonio Maravall, «directed» —focused on communication—, “massive” —of a popular nature— and “conservative” —to maintain the established order—. Any means of artistic expression had to be mainly didactic and seductive, it had to reach the public easily and it had to excite them, make them agree with the message it transmitted, a message put at the service of the instances of power —political or religious—, which was the one that paid for the production costs of artistic works, since the Church and the aristocracy —also incipiently the bourgeoisie— were the main patrons of artists and writers. If the Church wanted to transmit its counter-reformation message, the absolute monarchies saw in art a way to magnify their image and show their power, through monumental and pompous works that conveyed an image of greatness and helped to consolidate the centralist power of the monarch. reasserting his authority.

For this reason and despite the economic crisis, art flourished thanks above all to ecclesiastical and aristocratic patronage. The courts of the monarchical states —especially the absolutists— favored art as a way of capturing the magnificence of their kingdoms, a propaganda instrument that attested to the magnificence of the monarch (a paradigmatic example is the construction of Versailles by Louis XIV). The rise of collecting, which entailed the circulation of artists and works of art throughout the European continent, led to the rise of the art market. Some of the main art collectors of the time were monarchs, such as Emperor Rudolf II, Charles I of England, Philip IV of Spain or Queen Cristina of Sweden. The art market flourished notably, focused mainly on the Dutch (Antwerp and Amsterdam) and German (Nuremberg and Augsburg) spheres. Art academies also proliferated —following in the wake of those that emerged in Italy in the XVI century—, as institutions in charge of preserving art as a cultural phenomenon, to regulate its study and conservation, and to promote it through exhibitions and competitions; The main academies that emerged in the 17th century were the Académie Royale d'Art, founded in Paris in 1648, and the Akademie der Künste in Berlin (1696)

The Baroque style

The Baroque was a style heir to mannerist skepticism, which was reflected in a feeling of fatality and drama among the authors of the time. Art became more artificial, more ornate, decorative, ornate. He highlighted the illusionistic use of optical effects; beauty sought new ways of expression and the astonishing and surprising effects became relevant. New aesthetic concepts arose such as «wit», «insight» or «sharpness». In personal conduct, the external appearance stood out above all, so that it reflected a haughty, elegant, refined and exaggerated attitude that received the name of préciosité.

According to Wölfflin, the Baroque is defined mainly by opposition to the Renaissance: compared to the Renaissance linear vision, the Baroque vision is pictorial; compared to the composition in planes, the one based on depth; in front of the closed form, the open one; in front of the compositional unity based on harmony, the subordination to a main motive; compared to the absolute clarity of the object, the relative clarity of the effect. Thus, the Baroque "is the style of the pictorial point of view with perspective and depth, which submits the multiplicity of its elements to a central idea, with a vision without limits and a relative obscurity that avoids sharp details and outlines, while at the same time being a style that, instead of revealing its art, hides it."

Baroque art expressed itself stylistically in two ways: on the one hand, there is an emphasis on reality, the mundane aspect of life, everydayness and the ephemeral nature of life, which materialized in a certain «vulgarization» of the religious phenomenon in Catholic countries, as well as in a greater taste for the sensible qualities of the surrounding world in Protestants; on the other hand, a grandiloquent and exalted vision of national and religious concepts is manifested as an expression of power, which translates into a taste for the monumental, the lavish and ornate, the magnificent character given to royalty and the Church, to often with a strong propaganda stamp.

The Baroque was a culture of the image, where all the arts came together to create a total work of art, with a theatrical, scenographic aesthetic, a mise en scène that reveals the splendor of the dominant power (Church or State), with certain naturalistic touches but in a set that expresses dynamism and vitality. The interaction of all the arts expresses the use of visual language as a means of mass communication, embodied in a dynamic conception of nature and surrounding space.

One of the main characteristics of Baroque art is its illusory and artificial character: “ingenuity and design are the magical art through which one can fool the eye until astonishing” (Gian Lorenzo Bernini). The visual and ephemeral were especially valued, which is why theater and the various genres of performing arts and shows gained popularity: dance, pantomime, musical drama (oratorio and melodrama), puppet shows, acrobatics, circus, etc. There was a feeling that the world is a theater (theatrum mundi) and life a theatrical performance: "all the world is a stage, and all men and women mere actors" (As , William Shakespeare, 1599). In the same way, the other arts tended to be dramatized, especially architecture. It is an art that is based on the inversion of reality: in "simulation", in turning the false into true, and in "dissimulation", passing the true for false. Things are not shown as they are, but as one would like them to be, especially in the Catholic world, where the Counter-Reformation had little success, since half of Europe went over to Protestantism. In literature, it manifested itself by giving free rein to rhetorical artifice, as a means of propaganda expression in which the sumptuousness of the language tried to reflect reality in a sweetened way, resorting to rhetorical figures such as metaphor, paradox, hyperbole, antithesis, hyperbaton., the ellipsis, etc. This transposition of reality, which is distorted and magnified, altered in its proportions and subjected to the subjective criterion of fiction, also passed to the field of painting, where foreshortening and illusionistic perspective are abused for the sake of greater, striking effects. and surprising.

Baroque art sought to create an alternate reality through fiction and illusion. This trend had its maximum expression in the party and the playful celebration; buildings such as churches or palaces, or a neighborhood or an entire city, became theaters of life, on stages where reality and illusion were mixed, where the senses were subjected to deception and artifice. In this regard, the Counter-Reformation Church had a special role, which sought through pomp and pageantry to show its superiority over the Protestant churches, with acts such as solemn masses, canonizations, jubilees, processions or papal investitures. But just as lavish were the celebrations of the monarchy and the aristocracy, with events such as coronations, royal weddings and births, funerals, ambassador visits or any event that allowed the monarch to display his power to admire the people. Baroque festivals involved a combination of all the arts, from architecture and plastic arts to poetry, music, dance, theater, fireworks, flower arrangements, water games, etc. Architects such as Bernini or Pietro da Cortona, or Alonso Cano and Sebastián Herrera Barnuevo in Spain, contributed their talent to such events, designing structures, choreography, lighting and other elements, which often served as a testing ground for future, more serious achievements: thus, the canopy for the canonization of Saint Elizabeth of Portugal served Bernini for his future design of the canopy of Saint Peter, and the quarantore (Jesuit sacred theater) by Carlo Rainaldi was a model of the church of Santa Maria in Campitelli.

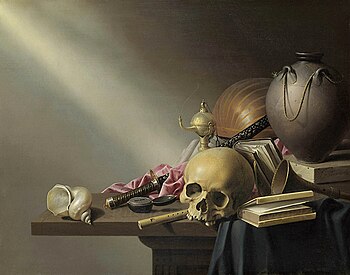

During the Baroque, the ornamental, artificial and ornate character of the art of this time revealed a transitory sense of life, related to the memento mori, the ephemeral value of riches in the face of the inevitability of death. death, parallel to the pictorial genre of vanitas. This feeling led to value in a vitalistic way the transience of the moment, to enjoy the slight moments of recreation that life grants, or the celebrations and solemn acts. Thus, births, weddings, deaths, religious acts, or royal coronations and other recreational or ceremonial acts, were dressed in a pomp and artificiality of a scenic nature, where large assemblies were made that brought together architecture and decorations to provide an eloquent magnificence. to any celebration, which became a spectacle of an almost cathartic nature, where the illusory element, the attenuation of the border between reality and fantasy, gained special relevance.

It should be noted that the Baroque is a heterogeneous concept that did not present a stylistic unity neither geographically nor chronologically, but that within it there are various stylistic trends, mainly in the field of painting. The main ones would be: naturalism, a style based on the observation of nature but subject to certain guidelines established by the artist, based on moral and aesthetic criteria or, simply, derived from the free interpretation of the artist when conceiving his work.; realism, a trend arising from the strict imitation of nature, neither interpreted nor sweetened, but meticulously represented even in its smallest details; classicism, current focused on the idealization and perfection of nature, evocative of high feelings and deep reflections, with the aspiration of reflecting beauty in all its fullness.

- Styles

Finally, it should be noted that new pictorial genres arose or developed in the Baroque. If until then the representation of historical, mythological or religious themes had prevailed in art, the profound social changes experienced in the XVII century They fostered interest in new topics, especially in Protestant countries, whose severe morality prevented the representation of religious images as they were considered idolatry. On the other hand, the rise of the bourgeoisie, which decidedly invested in art to highlight its status, brought with it the representation of new themes far removed from the grandiose scenes preferred by the aristocracy. Among the profusely developed genres in the Baroque, the following stand out: genre painting, which takes its models from the surrounding reality, from daily life, from peasant or urban themes, from poor and beggars, merchants and artisans, or from festivals and folkloric environments.; the landscape, which elevates the representation of nature to an independent category, which until then only served as a backdrop for scenes with historical or religious figures; the portrait, which focuses its representation on the human figure, generally with a realistic component although sometimes not exempt from idealization; the still life or still life, which consists of the representation of inanimate objects, whether they are pieces of household trousseau, flowers, fruit or other food, furniture, musical instruments, etc.; and the vanitas, a type of still life that alludes to the ephemeral nature of human existence, generally symbolized by the presence of skulls or skeletons, or candles or hourglasses.

- Gender

Architecture

Baroque architecture assumed more dynamic forms, with exuberant decoration and a scenic sense of shapes and volumes. The modulation of space became relevant, with a preference for concave and convex curves, paying special attention to optical games (trompe-l'œil) and the viewer's point of view. Urbanism also gained great importance, due to the monumental programs developed by kings and popes, with an integrating concept of architecture and landscape that sought to recreate a spatial continuum, of the expansion of the shapes towards infinity, as an expression of high ideals, whether political or religious. Bruno Zevi, architect and historian, synthetically defines the essence of Baroque architecture, «Baroque is spatial liberation, it is mental liberation from the norms of treatise writers, from conventions, from elementary geometry and from everything static, it is also liberation from symmetry and the antithesis between internal space and external space. Due to this desire for liberation, the Baroque achieves a psychological significance, which transcends to the architecture of the XVII and centuries. style="font-variant:small-caps;text-transform:lowercase">XVIII, achieving a state of mind of freedom, a creative attitude freed from intellectual and formal prejudices».

Italy

As in the previous era, the engine of the new style was once again Italy, thanks mainly to the patronage of the Church and the great architectural and urban programs developed by the pontifical headquarters, eager to show the world its victory against the Reform. The main constructive modality of Italian Baroque architecture was the church, which became the greatest exponent of Counter-Reformation propaganda. Italian Baroque churches are characterized by an abundance of dynamic forms, with a predominance of concave and convex curves, with façades richly decorated and full of sculptures, as well as a large number of columns, which often detach from the wall, and with interiors where the curved shape and profuse decoration also predominate. Among his various floor plans he highlighted —especially between the end of the XVI century and the beginning of the XVII— the design in two bodies, with two concentric pediments (curved on the outside and triangular on the inside), following the model of the façade of the Church of the Gesù by Giacomo della Porta (1572).

One of its first representatives was Carlo Maderno, author of the façade of St. Peter's in the Vatican (1607-1612) —whom he also modified the plan from a Greek cross projected by Bramante to a Latin cross—, and the church of Santa Susana (1597-1603). But one of the greatest promoters of the new style was the architect and sculptor Gian Lorenzo Bernini, the main architect of the monumental Rome we know today: St. Peter's baldachin (1624-1633) —where the Solomonic column appears, later one of the distinctive signs of the Baroque—, colonnade of Saint Peter's Square (1656-1667), Saint Andrew of the Quirinal (1658-1670), Chigi-Odescalchi Palace (1664-1667). The other great name of the time is Francesco Borromini, a highly inventive architect who subverted all the rules of classical architecture —to which, despite everything, Bernini still clung—, through the use of warped surfaces, ribbed vaults and mixtilinear arches., creating an architecture of an almost sculptural character. 1661). The third renowned architect active in Rome was Pietro da Cortona, who was also a painter, a circumstance perhaps for which he created volumes of great plasticity, with great contrasts of light and shadow (Santa Maria della Pace, 1656-1657; Santi Luca e Martina, 1635-1650). Outside of Rome it is worth noting the figure of Baldassare Longhena in Venice, author of the church of Santa Maria della Salute (1631-1650); and Guarino Guarini and Filippo Juvara in Turin, the first author of the Shroud chapel (1667-1690), and the second of the Superga basilica (1717-1731).

- Italian Baroque Architecture

France

In France, under the reigns of Louis XIII and Louis XIV, a series of constructions of great lavishness began, which were intended to show the greatness of the monarch and the sublime and divine character of the absolutist monarchy. Although some Italian influence is perceived in French architecture, it was reinterpreted in a more sober and balanced way, more faithful to Renaissance classicism, which is why French art of the time is often referred to as French classicism.

The first notable works were carried out by Jacques Lemercier (Sorbonne chapel, 1635-1642) and François Mansart (Maisons-Lafitte palace, 1624-1626; Val-de-Grâce church, 1645-1667). Subsequently, the great court programs focused on the new façade of the Louvre Palace, by Louis Le Vau and Claude Perrault (1667-1670) and, especially, on the Palace of Versailles, by Le Vau and Jules Hardouin-Mansart (1669- 1685). Of this last architect, it is also worth highlighting the church of San Luis des Invalides (1678-1691), as well as the layout of the Place Vendôme in Paris (1685-1708).

- French Baroque Architecture

Spain

In Spain, the architecture of the first half of the XVII century showed the Herrerian heritage, with an austerity and geometric simplicity of Escorial influence. The Baroque was gradually introduced, especially in the ornate interior decoration of churches and palaces, where the altarpieces evolved towards levels of ever higher magnificence. In this period, Juan Gómez de Mora was the most prominent figure, being the author of the Clerecía de Salamanca (1617), the Town Hall (1644-1702) and the Plaza Mayor in Madrid (1617-1619). Other authors of the time were: Alonso Carbonel, author of the Buen Retiro Palace (1630-1640); Pedro Sánchez and Francisco Bautista, authors of the Collegiate Church of San Isidro in Madrid (1620-1664).

Towards the middle of the century, the richest shapes and the freest and most dynamic volumes were gaining ground, with naturalistic decorations (garlands, plant cartouches) or abstract shapes (moldings and cut-out moldings, generally in a mixtilinear shape). At this time it is worth remembering the names of Pedro de la Torre, José de Villarreal, José del Olmo, Sebastián Herrera Barnuevo and, especially, Alonso Cano, author of the facade of the Granada Cathedral (1667).

Between the end of the 17th century and the beginning of the XVIII the Churrigueresque style (by the Churriguera brothers) was given, characterized by its exuberant decorativeness and the use of Solomonic columns: José Benito Churriguera was the author of the Main Altarpiece of San Esteban de Salamanca (1692) and the façade of the palace-church of Nuevo Baztán in Madrid (1709-1722); Alberto Churriguera designed the Plaza Mayor of Salamanca (1728-1735); and Joaquín Churriguera was the author of the Colegio de Calatrava (1717) and the cloister of San Bartolomé (1715) in Salamanca, of Plateresque influence. Other figures of the time were: Teodoro Ardemans, author of the façade of the Madrid City Hall and the first project for the Royal Palace of La Granja de San Ildefonso (1718-1726); Pedro de Ribera, author of the Toledo Bridge (1718-1732), the Conde-Duque Barracks (1717) and the façade of the church of Nuestra Señora de Montserrat in Madrid (1720); Narciso Tomé, author of the Transparent of the Cathedral of Toledo (1721-1734); the German Konrad Rudolf, author of the facade of the Cathedral of Valencia (1703); Jaime Bort, architect of the facade of the Murcia Cathedral (1736-1753); Vicente Acero, who designed the cathedral of Cádiz (1722-1762); and Fernando de Casas Novoa, author of the Obradoiro façade of the Santiago de Compostela Cathedral (1739-1750).

Other European countries

In Germany, no significant construction began until the middle of the century, due to the Thirty Years' War, and even then the main works were commissioned to Italian architects. However, at the end of the century there was an emergence of highly valued German architects, who created works whose innovative solutions already pointed to the Rococo: Andreas Schlüter, author of the Royal Palace of Berlin (1698-1706), influenced by Versailles; Matthäus Daniel Pöppelmann, author of the Dresden Zwinger Palace (1711-1722); and Georg Bähr, author of the Dresden Frauenkirche Church (1722-1738). In Austria, Johann Bernhard Fischer von Erlach, author of the church of San Carlos Borromeo in Vienna (1715-1725); Johann Lukas von Hildebrandt, author of the Belvedere Palace in Vienna (1713-1723); and Jakob Prandtauer, architect of the Melk Abbey (1702-1738). In Switzerland it is worth mentioning the Einsiedeln Abbey (1691-1735), by Kaspar Moosbrugger; the Jesuit church of Solothurn (1680), by Heinrich Mayer; and the Collegiate Church of Sankt Gallen (1721-1770), by Kaspar Moosbrugger, Michael Beer and Peter Thumb. In England, a Renaissance classicism of Palladian influence survived for a good part of the 17th century, whose greatest representative was Inigo Jones. Subsequently, the new forms of the continent were introduced, although reinterpreted again with a surviving sense of restraint and containment of the Palladian tradition. In this sense, the masterpiece of the period was Christopher Wren's St. Paul's Cathedral in London (1675-1711). Other notable works include Castle Howard (1699-1712) and Blenheim Palace (1705-1725), both by John Vanbrugh and Nicholas Hawksmoor.

In Flanders, Baroque forms, present in an overflowing decorativeness, coexisted with old Gothic structures, classical orders and Mannerist decoration: it is worth noting the churches of Saint-Loup de Namur (1621), Sint-Michiel de Leuven (1650- 1666), Saint-Jean-Baptiste of Brussels (1657-1677) and Sint-Pieter of Mechelen (1670-1709). In the Netherlands, Calvinism determined a simpler and more austere architecture, with classical lines, with a preponderance of civil architecture: the Amsterdam Stock Exchange (1608), by Hendrik de Keyser; Mauritshuis Palace in The Hague (1633-1644), by Jacob van Campen; Amsterdam City Hall (1648, now the Royal Palace), by Jacob van Campen.

In the Nordic countries, Protestantism also fostered a sober and classical architecture, with models imported from other countries, and its own characteristics that are only perceptible in the use of various materials, such as the combined walls of brick and stonework, or copper roofs. In Denmark, the Copenhagen Stock Exchange building (1619-1674) by Hans van Steenwinkel the Younger stands out; and the church of Frederick V (1754-1894), by Nicolai Eigtved. In Sweden, it is worth mentioning the Drottningholm Palace (1662-1685) and the Riddarholm Church (1671), by Nicodemus Tessin the Elder, and the Royal Palace in Stockholm (1697-1728), by Nicodemus Tessin the Younger.

In Portugal, it was not until the middle of the century —with the independence from Spain— that major construction activity began, favored by the discovery of gold and diamond mines in Minas Gerais (Brazil), which led King John V to wanting to emulate the courts of Versailles and the Vatican. The main constructions include: the Mafra National Palace (1717-1740), by Johann Friederich Ludwig; the Royal Palace of Queluz (1747), by Mateus Vicente; and the Sanctuary of Bom Jesus do Monte, in Braga (1784-1811), by Manuel Pinto Vilalobos.

In Eastern Europe, Prague (Czech Republic) was one of the cities with the greatest construction program, favored by the Czech aristocracy: Czernin Palace (1668-1677), by Francesco Caratti; Archiepiscopal Palace (1675-1679), by Jean-Baptiste Mathey; St. Nicholas Church (1703-1717), by Christoph Dientzenhofer; Sanctuary of the Virgin of Loreto (1721), by Christoph and Kilián Ignác Dientzenhofer. In Poland, the Cathedral of San Juan Bautista de Wroclaw (1716-1724), by Fischer von Erlach; the Krasiński Palace (1677-1682), by Tylman van Gameren; and the Wilanów Palace (1692), by Agostino Locci and Andreas Schlüter. Cathedral of Saint Peter and Saint Paul in Saint Petersburg (1703-1733), the work of the Italian architect Domenico Trezzini. Later, Francesco Bartolomeo Rastrelli was the exponent of a late Baroque with Franco-Italian influence, which already pointed to the Rococo: Peterhof Palace, called "the Russian Versailles" (1714-1764, initiated by Le Blond); Winter Palace in Saint Petersburg (1754-1762); and Catherine's Palace in Tsarskoye Selo (1752-1756). In Ukraine, the Baroque is distinguished from the Western by more restrained ornamentation and simpler forms: Kiev Cave Monastery, Vydubichi St. Michael Monastery in Kiev.

In the Ottoman Empire, Western art influenced traditional Islamic forms during the 18th century, as denoted in the Tulip Mosque (1760-1763), the work of Mehmet Tahir Ağa. Another exponent was the Nuruosmaniye Mosque (1748-1755), the work of the Greek architect Simon el Rum and sponsored by Sultan Mahmud I, who ordered plans for European churches to be brought for their construction.

Colonial architecture

Colonial Baroque architecture is characterized by profuse decoration (Portada de La Profesa, Mexico; facades covered in Puebla-style tiles, as in San Francisco Acatepec in San Andrés Cholula and San Francisco de Puebla), which would be exacerbated in the so-called "ultra-baroque" (Facade of the Tabernacle of the Cathedral of Mexico, by Lorenzo Rodríguez; Church of Tepotzotlán; Temple of Santa Prisca de Taxco). In Peru, the constructions developed in Lima and Cuzco since 1650 show some original characteristics that are even ahead of the European Baroque, such as the use of padded walls and Solomonic columns (Iglesia de la Compañía, Cuzco; San Francisco, Lima). In other countries, the following stand out: the Metropolitan Cathedral of Sucre in Bolivia; the sanctuary of the Lord of Esquipulas in Guatemala; the cathedral of Tegucigalpa in Honduras; the cathedral of León in Nicaragua; the Church of the Company in Quito, Ecuador; the church of San Ignacio in Bogotá, Colombia; the cathedral of Caracas in Venezuela; the Court of Buenos Aires in Argentina; the church of Santo Domingo in Santiago de Chile; and the cathedral of Havana in Cuba. It is also worth remembering the quality of the churches of the Jesuit missions in Paraguay and the Franciscan missions in California.

In Brazil, as in the metropolis, Portugal, the architecture has a certain Italian influence, generally Borrominesque, as can be seen in the churches of San Pedro dos Clérigos in Recife (1728) and Nuestra Señora de la Gloria in Outeiro (1733). In the Minas Gerais region, the work of Aleijadinho stood out, author of a group of churches that stand out for their curved planimetry, façades with dynamic concave-convex effects and a plastic treatment of all the architectural elements (São Francisco de Assis in Ouro Preto, 1765-1775).

In the Portuguese colonies of India (Goa, Damao and Diu) an architectural style of Baroque forms mixed with Hindu elements flourished, such as the Goa Cathedral (1562-1619) and the Basilica of the Good Jesus of Goa (1594- 1605), which houses the tomb of San Francisco Javier. Goa's collection of churches and nunneries was declared a World Heritage Site in 1986.

In the Philippines, the baroque churches of the Philippines (designated as a World Heritage Site in 1993) stand out, with a style that is a reinterpretation of European baroque architecture by the Chinese and Filipino artisans: San Agustín Church (Manila), Church of Our Lady of the Assumption (Santa María, Ilocos Sur), Church of San Agustín (Paoay, Ilocos Norte) and Church of Santo Tomás de Villanueva (Miagao, Iloílo).

Gardening

During the Baroque, gardening was closely linked to architecture, with rational designs where the preference for geometric shapes gained preference. His paradigm was the French garden, characterized by larger lawn areas and a new ornamental detail, the parterre, as in the Gardens of Versailles, designed by André Le Nôtre. The Baroque taste for theatricality and artificiality led to the construction of various accessory elements for the garden, such as artificial islands and grottoes, open-air theatres, ménageries of exotic animals, pergolas, triumphal arches, etc. The orangerie arose, a construction with large windows designed to protect orange trees and other plants of southern origin in winter. The Versailles model was copied by the great European monarchical courts, with exponents such as the gardens of Schönbrunn (Vienna), Charlottenburg (Berlin), La Granja (Segovia) and Petrodvorets (Saint Petersburg).

Sculpture

Baroque sculpture acquired the same dynamic, sinuous, expressive and ornamental character as architecture —with which it reached a perfect symbiosis, especially in religious buildings—, emphasizing movement and expression, starting from a naturalistic but deformed base at the whim of the artist. The evolution of sculpture was not uniform in all countries, since in areas such as Spain and Germany, where Gothic art had been well established —especially in religious imagery— certain stylistic forms of the local tradition still survived, while in countries where the Renaissance had supposed the implantation of the classic forms (Italy and France) the persistence of these is more accentuated. By theme, along with the religious, the mythological was quite important, especially in palaces, fountains and gardens.

In Italy Gian Lorenzo Bernini once again stood out, a sculptor by training although he worked as an architect commissioned by various popes. Influenced by Hellenistic sculpture —which in Rome he could study perfectly thanks to the papal archaeological collections—, he achieved great mastery in the expression of movement, in fixing the action stopped in time. He was the author of works as relevant as Aeneas, Anchises and Ascanio fleeing from Troy (1618-1619), The kidnapping of Proserpina (1621-1622), Apollo and Daphne (1622-1625), David Throwing His Sling (1623-1624), the Tomb of Urban VIII (1628-1647), Ecstasy of Saint Teresa (1644-1652), the Fountain of the Four Rivers in Piazza Navona (1648-1651) and Death of Blessed Ludovica Albertoni (1671-1674). Other sculptors of the time included: Stefano Maderno, halfway between Mannerism and Baroque (Santa Cecilia, 1600); François Duquesnoy, Flemish by birth but active in Rome (Saint Andrew, 1629-1633); Alessandro Algardi, trained in the Bolognese school, classical in style (Beheading of Saint Paul, 1641-1647; Pope Saint Leo arresting Attila, 1646-1653); and Ercole Ferrata, disciple of Bernini (The death at the stake of Saint Agnes, 1660).

In France, sculpture was the heir to Renaissance classicism, with preeminence of the decorative and courtly aspect, and of mythological themes. Jacques Sarrazin trained in Rome, where he studied classical sculpture and the work of Michelangelo, whose influence is evident in his Caryatids in the Louvre's Pavillon de l'Horloge (1636). François Girardon worked on the decoration of Versailles, and is remembered for his Mausoleum of Cardinal Richelieu (1675-1694) and for the group of Apollo and the Nymphs of Versailles (1666 -1675), inspired by the Apollo de Belvedere of Leochares (circa 330 BC-300 BC). Antoine Coysevox also participated in the Versailles project, and among his productions the Glorification of Louis XIV in the War Room of Versailles (1678) and the Mazarin Mausoleum (1689-1693). Pierre Puget was the most original of the French sculptors of the time, although he did not work in Paris, and his taste for drama and violent movement distanced him from the classicism of his surroundings: Milo of Crotona (1671 -1682), inspired by Laocoonte.

In Spain, religious imagery of Gothic heritage lasted, generally in polychrome wood —sometimes with the addition of authentic clothing—, present either in altarpieces or as a free-standing figure. Two schools are usually distinguished in the first phase: the Castilian, centered in Madrid and Valladolid, where Gregorio Fernández stands out, who evolved from a mannerism influenced by Jun to a certain naturalism (Cristo recumbent, 1614; Baptism of Christ, 1630), and Manuel Pereira, of a more classical style (San Bruno, 1652); In the Andalusian school, active in Seville and Granada, the following stand out: Juan Martínez Montañés, with a classicist style and figures that denote a detailed anatomical study (Crucified Christ, 1603; Immaculate Conception, 1628-1631); his disciple Juan de Mesa, more dramatic than the teacher ( Jesús del Gran Poder , 1620); Alonso Cano, also a disciple of Montañés, and like him a content classicist (Immaculate Conception, 1655; San Antonio de Padua, 1660-1665); and Pedro de Mena, a disciple of Cano, with a sober but expressive style (Penitent Magdalena, 1664). Since the middle of the century, the "full baroque" has been produced, with a strong Berninian influence, with figures such as Pedro Roldán (Main Altarpiece of the Hospital de la Caridad in Seville, 1674) and Pedro Duque Cornejo (Choir stalls of the Cathedral of Córdoba, 1748). Already in the 18th century the Levantine school stood out in Murcia and Valencia, with names like Ignacio Vergara or Nicolás de Bussi, and the The main figure of Francisco Salzillo, with a sensitive and delicate style that points to the Rococo (Oración del Huerto, 1754; Prendimiento, 1763).

In southern Germany and Austria, sculpture had a great boom in the 17th century thanks to the Counter-Reformation impulse, after the previous Protestant iconoclasm. Initially, the most relevant works were commissioned from Dutch artists, such as Adriaen de Vries (Affliction of Christ, 1607). The German names include: Hans Krumper (Patrona Bavariae, 1615); Hans Reichle, disciple of Giambologna (choir and group of The Crucifixion of the Cathedral of Saint Ulric and Saint Afra in Augsburg, 1605); Georg Petel (Ecce Homo, 1630); Justus Glesker (Crucifixion Group, 1648-1649); and Andreas Schlüter, also an architect, who received Berninian influence (Equestrian statue of the Great Elector Frederick William I of Brandenburg, 1689-1703). In England, the Italian influence was combined, present especially in the dynamic drama of funerary monuments, and the French, whose classicism is more appropriate for statues and portraits. The most important English sculptor of the time was Nicholas Stone, trained in Holland, author of funerary monuments such as that of Lady Elisabeth Carey (1617-1618) or that of sir William Curle (1617).

In the Netherlands, Baroque sculpture was limited to a single name of international fame, the also architect Hendrik de Keyser, trained in Italian mannerism (Funerary monument of William I, 1614-1622). In Flanders, on the other hand, numerous sculptors did emerge, many of whom settled in the neighboring country, such as Artus Quellinus, author of the sculptural decoration of the Amsterdam City Hall. Other Flemish sculptors included: Lukas Fayd'herbe (Tomb of Archbishop André Cruesen, 1666); Rombout Verhulst (Tomb of Johan Polyander van Kerchoven, 1663); and Hendrik Frans Verbruggen (Pulpit of the Cathedral of Saint Michael and Saint Gudula in Brussels, 1695-1699).

In America, the sculptural work developed in Lima stood out, with authors such as the Catalan Pedro de Noguera, initially in a mannerist style, which evolved towards the Baroque in works such as the stalls of the cathedral of Lima; Gomes Hernández Galván, from Valladolid, author of the Tables of the Cathedral; Juan Bautista Vásquez, author of a sculpture of the Virgin known as La Rectora, currently at the Riva-Agüero Institute; and Diego Rodrigues, author of the image of the Virgin of Copacabana in the Shrine of the same name in the Rimac District of Lima. In Mexico, the Zamoran Jerónimo de Balbás, author of the Altarpiece of the Kings of the Metropolitan Cathedral of Mexico City, stood out. In Ecuador, the Quito school stood out, represented by Bernardo de Legarda and Manuel Chili (nicknamed Caspicara). In Brazil, the figure of Aleijadinho stood out again, who was in charge of the sculptural decoration of his architectural projects, such as the church of São Francisco de Assis in Ouro Preto, where he made the sculptures on the façade, the pulpit and the altar; or the Sanctuary of Bom Jesus de Congonhas, where the figures of the twelve prophets stand out.

Painting

Baroque painting had a marked geographical differentiating accent, since its development occurred by country, in various national schools, each with a distinctive stamp. However, a common influence again coming from Italy is perceived, where two opposing tendencies arose: naturalism (also called caravagism), based on the imitation of natural reality, with a certain taste for chiaroscuro —the so-called tenebrism—; and classicism, which is just as realistic but with a more intellectual and idealized concept of reality. Later, in the so-called «full baroque» (second half of the XVII century), painting evolved into a more decorative style, with a predominance of mural painting and a certain predilection for optical effects (trompe-l'oeil) and luxurious and exuberant scenery.

Italy

As we have seen, in the first place two opposing tendencies arose, naturalism and classicism. The first had its greatest exponent in Caravaggio, an original artist with a hazardous life who, despite his premature death, left numerous masterpieces in which the meticulous description of reality and the almost vulgar treatment of characters with a vision are synthesized. not exempt from intellectual reflection. Likewise, he was an introducer of gloom, where the characters stand out against a dark background, with artificial and directed lighting, with a theatrical effect, which highlights the objects and the gestures and attitudes of the characters. Among Caravaggio's works, the following stand out: Crucifixion of Saint Peter (1601), The Calling of Saint Matthew (1602), Burial of Christ (1604), etc. Other naturalist artists were: Bartolomeo Manfredi, Carlo Saraceni, Giovanni Battista Caracciolo, and Orazio and Artemisia Gentileschi. Also worth mentioning in relation to this style is a genre of paintings known as "bambochadas" (after the Rome-based Dutch painter Pieter van Laer, nicknamed il Bamboccio), which focuses on the depiction of vulgar characters such as beggars, gypsies, drunkards or homeless people.

The second trend was classicism, which arose in Bologna, around the so-called Bolognese school, started by the brothers Annibale and Agostino Carracci. This trend was a reaction against mannerism, seeking an idealized representation of nature, representing it not as it is, but as it should be. His sole objective was ideal beauty, for which he was inspired by classical Greco-Roman art and Renaissance art. This ideal found a suitable subject of representation in the landscape, as well as in historical and mythological subjects. The Carracci brothers initially worked together (frescoes from Palazzo Fava in Bologna), until Annibale was called to Rome to decorate the vault of Palazzo Farnese (1597-1604), which for its quality has been compared to the Sistine Chapel. Other members of the school were: Guido Reni (Hippomenes and Atalanta, 1625), Domenichino (The Hunt for Diana, 1617), Francesco Albani (The Four Elements , 1627), Guercino (La Aurora, 1621-1623) and Giovanni Lanfranco (Assumption of the Virgin, 1625-1627).

Lastly, in the «full baroque» the process started in architecture and sculpture culminated, tending towards monumentality and decorativeness, to ornate and bombastic figuration, with a taste for horror vacui and illusionary effects. One of his great teachers was the architect Pietro da Cortona, influenced by Venetian and Flemish painting, author of the decoration of the Barberini and Pamphili palaces in Rome and Pitti in Florence. Other artists were: il Baciccia, author of the frescoes in the church of the Gesù (1672-1683); Andrea Pozzo, who decorated the vault of the church of San Ignacio in Rome (1691-1694); and the Neapolitan Luca Giordano, architect of the decoration of the Palazzo Medici-Riccardi in Florence (1690), and who also worked in Spain, where he is known as Lucas Jordán.

France

In France there were also the two currents that emerged in Italy, naturalism and classicism, although the first did not have excessive popularity, due to the classicist taste of French art since the Renaissance, and it occurred mainly in the provinces and in bourgeois circles and ecclesiastical, while the second was adopted as "official art" by the monarchy and the aristocracy, which gave it its own hallmarks with the coining of the term French classicism. The main naturalist painter was Georges de La Tour, in whose work two phases can be distinguished, one focused on the representation of popular types and humorous scenes, and another where religious themes predominate, with a radical tenebrism where the figures are glimpsed with dim lights. of candles or candle lamps: Penitent Magdalene (1638-1643), Saint Sebastian cared for by Saint Irene (1640). The Le Nain brothers (Antoine, Louis and Mathieu) are also included in this current, focused on peasant themes but far from tenebrism, and with a certain bambochante influence.

Classicist painting focuses on two great painters who spent most of their careers in Rome: Nicolas Poussin and Claude Lorrain. The first received the influence of Rafaelesque painting and the Bolognese school, and created a type of representation of scenes —generally mythological in theme— where he evokes the splendid past of Greco-Roman antiquity as an idealized paradise of perfection, a golden age of humanity, in works such as: The Triumph of Flora (1629) and The Shepherds of Arcadia (1640). For his part, Lorrain reflected in his work a new concept in the elaboration of the landscape based on classical references —the so-called “ideal landscape”—, which shows an ideal conception of nature and man. In his works, the use of light stands out, to which he gives paramount importance when conceiving the painting: Landscape with the embarkation in Ostia of Santa Paula Romana (1639), Port with the embarkation of the Queen of Sheba (1648).

In the height of the Baroque, painting was framed more in the courtly circle, where it was directed mainly towards portraiture, with artists such as Philippe de Champaigne (Portrait of Cardinal Richelieu, 1635-1640), Hyacinthe Rigaud (Portrait of Louis XIV, 1701) and Nicolas de Largillière (Portrait of a young Voltaire, 1718). Another aspect was that of academic painting, which sought to lay the foundations of the pictorial trade on the basis of classicist ideals that, in the long run, ended up constraining it in rigid repetitive formulas. Some of his representatives were: Simon Vouet (Presentation of Jesus in the Temple, 1641), Charles Le Brun (Entry of Alexander the Great into Babylon, 1664), Pierre Mignard (Perseus and Andromeda, 1679), Antoine Coypel (Louis XIV resting after the Peace of Nijmegen, 1681) and Charles de la Fosse (Kidnapping of Proserpina, 1673).

Spain

In Spain, despite the economic and political decline, painting reached levels of high quality, which is why it is common to speak, in parallel to literature, of a "Golden Age" of Spanish painting. Most of the production was religious-themed, practicing to a lesser extent genre painting, portraiture and still life —especially vanitas—. The Italian and Flemish influence is perceived, which arrives above all through prints: the first is produced in the first half of the XVII century, with a predominance of tenebrist naturalism; and the second in the following half century and beginning of the XVIII, of Rubenian origin.

In the first half of the century, three schools stand out: the Castilian (Madrid and Toledo), the Andalusian (Seville) and the Valencian. The first has a strong court stamp, as it is the seat of the Hispanic monarchy, and still denotes a strong influence from Escorial, perceptible in the realistic and austere style of art produced at that time. Some of its representatives are: Bartolomé and Vicente Carducho, Eugenio Cajés, Juan van der Hamen and Juan Bautista Maíno, in Madrid; Luis Tristán, Juan Sánchez Cotán and Pedro Orrente, in Toledo. In Valencia, Francisco Ribalta stood out, with a realistic and colorful style, with a Counter-Reformation theme (San Bruno, 1625). Also usually included in this school, although he worked mainly in Italy, is José de Ribera, with a tenebrist style but with a coloring of Venetian influence (Sileno borracho, 1626; The martyrdom of San Felipe , 1639). In Seville, after a first generation that still shows Renaissance influence (Francisco Pacheco, Juan de Roelas, Francisco de Herrera el Viejo), three great masters arose who elevated Spanish painting of the time to great heights: Francisco de Zurbarán, Alonso Cano and Diego Velazquez. Zurbarán devoted himself mainly to religious themes —especially in monastic environments—, although he also practiced portraiture and still life, with a simple but effective style, with great attention to detail: Saint Hugo in the Carthusian refectory (1630), Fray Gonzalo de Illescas (1639), Santa Casilda (1640). Alonso Cano, also an architect and sculptor, evolved from an accentuated tenebrism to a certain classicism of Venetian inspiration: Christ died in the arms of an angel (1650), Presentation of the Virgin in the Temple (1656).

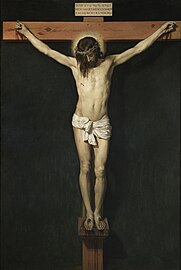

Diego Velázquez was undoubtedly the most genius artist of the time in Spain, and one of the most renowned internationally. He trained in Seville, in the workshop of what would be his father-in-law, Francisco Pacheco, and his first works are framed in the naturalistic style in vogue at the time. In 1623 he settled in Madrid, where he became Philip IV's chamber painter, and his style evolved thanks to contact with Rubens (whom he met in 1628) and his study of the Venetian school and Bolognese classicism, which he met in a trip to Italy in 1629-1631. Then he abandoned gloom and ventured into an in-depth study of pictorial lighting, of the effects of light both on objects and in the environment, with which he reaches heights of great realism in the representation of his scenes, which, however, are not it is devoid of an air of classical idealization, which shows a clear intellectual background that for the artist was a vindication of the profession of painter as a creative and elevated activity. His works include: The waterboy of Seville (1620), The drunkards (1628-1629), The forge of Vulcano (1630), The Surrender of Breda (1635), Crucified Christ (1639), Venus in the Mirror (1647-1651), Portrait of Innocent X (1649), Las Meninas (1656) and Las hilanderas (1657).

In the second half of the century the main artistic centers were Madrid and Seville. In the capital, naturalism was replaced by colorful Flemish and the decorative art of full Italian Baroque, with artists such as: Antonio de Pereda (The Knight's Dream, 1650); Juan Ricci (Immaculate Conception, 1670); Francisco de Herrera el Mozo (Apotheosis of San Hermenegildo, 1654); Juan Carreño de Miranda (Foundation of the Trinitarian Order, 1666); Juan de Arellano (Vase, 1660); José Antolínez (The transit of the Magdalena, 1670); Claudio Coello (Carlos II adoring the Sacred Form, 1685); and Antonio Palomino (decoration of the Tabernacle of the Cartuja de Granada, 1712). In Seville, the work of Bartolomé Esteban Murillo stood out, focused on the representation above all of Immaculate Conception and Child Jesus —although he also did portraits, landscapes and genre scenes—, with a delicate and sentimental tone, but with great technical mastery and chromatic virtuosity: Adoration of the Shepherds (1650); Immaculate Conception (1678). Together with him, Juan de Valdés Leal stood out, the antithesis of Murillo's beauty, with his predilection for vanitas and a dynamic and violent style, which despises drawing and focuses on color, on pictorial matter: canvases of the Last Days of the Hospital de la Caridad in Seville (1672).

Flanders and Holland

The political and religious separation of two areas that until the previous century had had a practically identical culture highlights the social tensions that existed in the century XVII: Flanders, still under Spanish rule, was Catholic and aristocratic, with religious-themed art predominating, while the newly independent Netherlands was Protestant and bourgeois, with secular art and more realistic, with a taste for portraits, landscapes and still lifes.

In Flanders, the main figure was Peter Paul Rubens, trained in Italy, where he was influenced by Michelangelo and the Venetian and Bolognese schools. In his workshop in Antwerp he employed a large number of collaborators and disciples, which is why his pictorial production stands out both for its quantity and its quality, with a dynamic, vital and colorful style, where anatomical rotundity stands out, with muscular men and women. sensual and fleshy: The landing of Marie de' Medici in the port of Marseilles (1622-1625), Minerva protects Pax from Mars (1629), The three Gracias (1636-1639), Kidnapping of the daughters of Leucippus (1636), Trial of Paris (1639), etc. His disciples were: Anton van Dyck, a great portrait painter with a refined and elegant style (Sir Endymion Porter and Anton van Dyck, 1635); Jacob Jordaens, specialized in genre scenes, with a taste for popular themes (The King drinks, 1659); and Frans Snyders, focused on still life (Still Life with Birds and Game, 1614).

In Holland, Rembrandt especially stood out, an original artist with a strong personal stamp, with a style close to gloomy but more diffused, without the marked contrasts between light and shadow typical of the Caravaggists, but rather a more subtle and diffuse penumbra. He cultivated all kinds of genres, from religious and mythological to landscape and still life, as well as portraiture, where his self-portraits stand out, which he practiced throughout his life. His works include: Anatomy Lesson by Dr. Nicolaes Tulp (1632), The Night Watch (1642), The Skinned Ox (1655), and The trustees of the clothiers (1662). Another relevant name is Frans Hals, a magnificent portrait painter, with a free and energetic brushstroke that predates Impressionism (Banquet of the Arquebusiers of Saint George in Haarlem, 1627). The third name of great relevance is Jan Vermeer, specialized in landscapes and genre scenes, to which he gave a great poetic, almost melancholic sense, where the use of light and light colors especially stands out, with an almost pointillist technique: View of Delft (1650), The Milkmaid (1660), The Letter (1662). The rest of the Dutch artists generally specialized in genres: interior and popular and domestic themes (Pieter de Hooch, Jan Steen, Gabriel Metsu, Gerard Dou, Utrecht Caravaggist School); landscape (Jan van Goyen, Jacob van Ruysdael, Meindert Hobbema, Aelbert Cuyp); and still life (Willem Heda, Pieter Claesz, Jan Davidsz de Heem).

Other countries

In Germany there was little pictorial production, due to the Thirty Years War, so many German artists had to work abroad, as is the case of Adam Elsheimer, a notable landscape painter attached to naturalism who worked in Rome (The flight into Egypt, 1609). Joachim von Sandrart also settled in Rome, a painter and writer who compiled various biographies of artists of the time (Teutschen Academie der Edlen Bau-, Bild- und Mahlerey-Künsten, 1675). Similarly, Johann Liss was on a pilgrimage between France, the Netherlands and Italy, so his work is very varied both stylistically and in genres ( The inspiration of Saint Jerome , 1627). Johann Heinrich Schönfeld spent a good part of his career in Naples, producing a work of classical style and Poussinian influence ( David's Triumphal Parade , 1640-1642). In Germany itself, the still life developed remarkably, with artists such as Georg Flegel, Johann Georg Hainz and Sebastian Stoskopff. In Austria, Johann Michael Rottmayr stood out, author of the frescoes in the Collegiate Church of Melk (1716-1722) and the Church of San Carlos Borromeo in Vienna (1726). In England, the scant native pictorial tradition meant that most commissions —generally portraits— were entrusted to foreign artists, such as the Flemish Anton van Dyck (Portrait of Charles I of England, 1638), or the German Peter Lely (Louise de Kéroualle, 1671).

America

The first influences were from Sevillian tenebrism, mainly Zurbarán —some of whose works are still preserved in Mexico and Peru—, as can be seen in the work of the Mexicans José Juárez and Sebastián López de Arteaga, and the Bolivian Melchor Perez de Holguin. The Cuzco School of painting arose as a result of the arrival of the Italian painter Bernardo Bitti in 1583, who introduced mannerism to America. He highlighted the work of Luis de Riaño, disciple of the Italian Angelino Medoro, author of the murals of the Andahuaylillas temple. The Indian painters Diego Quispe Tito and Basilio Santa Cruz Puma Callao also stood out, as well as Marcos Zapata, author of the fifty large canvases that cover the high arches of the Cathedral of Cuzco. In Ecuador, the Quito school was formed, represented mainly by Miguel de Santiago and Nicolás Javier de Goríbar.

In the 18th century the sculptural altarpieces began to be replaced by paintings, and Baroque painting developed notably in America. Likewise, the demand for civil works grew, mainly portraits of the aristocratic classes and the ecclesiastical hierarchy. The main influence was that of Murillo, and in some cases —as in Cristóbal de Villalpando— that of Valdés Leal. The painting of this period has a more sentimental tone, with sweeter and softer forms. Notable are Gregorio Vázquez de Arce in Colombia, and Juan Rodríguez Juárez and Miguel Cabrera in Mexico.

Graphic and decorative arts

The graphic arts had a great diffusion during the Baroque, continuing the boom that this sector had during the Renaissance. The rapid profusion of engravings throughout Europe led to the expansion of artistic styles originating in the centers of greatest innovation and production of the time, Italy, France, Flanders and the Netherlands —decisive, for example, in the evolution of art. Spanish painting. The most used techniques were etching and drypoint engraving. These procedures allow an artist to make a design on a copper plate in successive stages, which can be retouched and perfected on the fly. The various degrees of wear on the plates made it possible to make about 200 etching prints —although only the first 50 were of excellent quality—, and about 10 drypoint prints.

In the 17th century the main centers of engraving production were in Rome, Paris and Antwerp. In Italy it was practiced by Guido Reni, with a clear and firm drawing of a classicist style; and Claude Lorrain, author of high-quality etchings, especially in shading and the use of intertwining lines to suggest different tones, usually in landscapes. In France, the following stood out: Abraham Bosse, author of about 1,500 engravings, generally genre scenes; Jacques Bellange, author of religious representations, influenced by Parmigianino; and Jacques Callot, trained in Florence and specialized in figures of beggars and deformed beings, as well as scenes from the picaresque novel and the commedia dell'arte —his series of Great Miseries of War influenced Goya. In Flanders, Rubens founded a school of burilists to more effectively disseminate his work, among which Lucas Vorsterman I stood out; Anton van Dyck also cultivated etching. In Spain, engraving was practiced mainly by José de Ribera, Francisco Ribalta and Francisco Herrera el Viejo. One of the artists who used the engraving technique the most was Rembrandt, who reached levels of great mastery not only in drawing but also in painting. creation of contrasts between light and shadow. His engravings were highly valued, as can be seen with his etching Christ Healing a Sick (1648-1650), which sold for one hundred guilders, a record figure at the time.

The decorative and applied arts also expanded greatly in the 17th century, mainly due to the decorative and ornamental nature of the Baroque art, and the concept of "total work of art" that was applied to great architectural achievements, where interior decoration played a leading role, as a means of capturing the magnificence of the monarchy or the splendor of the Counter-Reformation Church. In France, the luxurious project for the Palace of Versailles led to the creation of the Manufacture Royale des Gobelins —directed by the king's painter, Charles Le Brun—, where all kinds of decorative objects were manufactured, mainly furniture, upholstery and goldsmithing. The manufacture of tapestries had a significant increase in its production, and was directed towards the imitation of painting, with the collaboration in numerous cases of renowned painters who made cartoons for tapestries, such as Simon Vouet, Le Brun himself or Rubens in Flanders. —a country that was also a great tapestry-producing center, which it exported to the entire continent, such as the magnificent tapestries of Triunfos del Santo Sacramento, made for the Descalzas Reales of Madrid.

Goldsmithing also reached high levels of production, especially in silver and precious stones. In Italy, a new technique arose to cover fabrics and objects such as altars or tabletops with semi-precious stones such as onyx, agate, carnelian or lapis lazuli. In France, like the rest of manufactures, it was subject to royal protection, and the profusion of silver objects was such that in 1672 a law was enacted that limited the production of objects made of this metal. Ceramics and glass generally continued with the same manufacturing techniques as in the Renaissance period, with white and blue pottery from Delft (Holland) and polished and cut glass from Bohemia standing out. The Murano glassmaker Nicola Mazzolà was the creator of a type of glass that imitated Chinese porcelain. He also continued to make stained glass windows for churches, such as those in the Parisian church of Saint-Eustache (1631), designed by Philippe de Champaigne.

One of the sectors that gained more relevance was cabinet-making, characterized by wavy surfaces (concave and convex), with volutes and various motifs such as cartouches and shells. In Italy, the following stood out: the Tuscan wardrobe with two bodies, with bronze balustrades and hard stone inlaid decoration; the Ligurian desk with two bodies, with carved and superimposed figures (bambochos); and the Venetian carved armchair (tronetto), exuberantly decorated. In Spain, the bargueño arose, a rectangular chest with handles, with numerous drawers and compartments. The Spanish furniture continued with the Mudejar-style decoration, while the Baroque was denoted in the curved shapes and the use of Solomonic columns in the beds. Even so, the austerity of a Counter-Reformation sign predominated, as denoted in the chair called frailero (or missional in Latin America). The golden age of cabinetmaking occurred in the France of the Louises, where high levels of quality and refinement were achieved, above all thanks to the work of André-Charles Boulle, creator of a new technique for applying metals (copper, tin) on organic materials (tortoiseshell, mother-of-pearl, ivory) or vice versa. Boulle's works include the two chests of drawers in the Trianon, in Versailles, and the pendulum clock with the Chariot of Apollo in Fontainebleau.

Literature

Baroque literature, like the rest of the arts, developed under absolutist political and counter-reformation religious precepts, and was characterized mainly by skepticism and pessimism, with a vision of life posed as a struggle, dream or lie, where everything is fleeting and perishable, and where the attitude towards life is doubt or disappointment, and prudence as a rule of conduct. His style was sumptuous and ornate, with highly adjective, allegorical and metaphorical language, and a use Frequent figure of rhetoric. The main genres that were cultivated were the utopian novel and bucolic poetry, which together with the theater —which is dealt with in another section due to its importance—, were the main vehicles of expression of baroque literature. As also happened with the rest of the arts, Baroque literature was not homogeneous throughout the continent, but various national schools were formed, each one with its peculiarities, a fact that fostered the rise of vernacular languages and the progressive abandonment of Latin..

In the crisis situation of the Baroque, each author decided to face this stage in a different way:

- The escapism: as the name itself indicates, the end to which the authors intended to arrive is to be able to get away and forget the socio-economic problems of the time through fantasies, glories, different realities or presenting an idealized world utopia where all the problems that may arise are easily solved and where it covers the order.

- The satire: other writers such as Quevedo or Góngora left their mark when using satire as a way of laughing the world and the situation in which they had touched them to live through the so-called spicy novels.

- Stoicism: it is a critique of the vanity of the world, the transientness of beauty, fame and life. Calderon de la Barca is the most outstanding author of this style for his work Sacramental cars.

- Morality: attempting to eradicate defects and vices, proposing more appropriate models of conduct according to the political and religious ideologies of their time.

In Italy, literature was forged on the foundations of the Renaissance realism-idealism dichotomy, as well as the predominance once again of religion over humanism. His main linguistic stamp was the use and abuse of the metaphor, which permeates everything, with a somewhat twisted aesthetic taste, with a preference for the deformed over the beautiful. The main current was Marinism -by Giambattista Marino-, a style bombastic and exaggerated that tries to surprise by the virtuosity of the language, without paying special attention to the content. For Marino, "the end of the poet is astonishment": his main work, Adonis (1623), stands out for its musicality and abundance of images, with an eloquent style and, despite everything easy to read. Other marine poets were: Giovanni Francesco Busenello, Emanuele Tesauro, Cesare Rinaldi, Giulio Strozzi, etc.

Preciosity arose in France, a current similar to marineism that gives special importance to the richness of language, with an elegant and mannered style. He was represented by Isaac de Benserade and Vincent Voiture in poetry, and Honoré d'Urfé and Madeleine de Scudéry in prose. Later on, classicism arose, which advocated a simple and austere style, subject to classical canons —such as the three Aristotelian units—, with a rigid metric regulation. Its initiator was François de Malherbe, whose rational and excessively rigid poetry subtracted any hint of emotionality, who was followed by: Jean de La Fontaine, an impeccable fabulist, with a didactic and moralizing intention; and Nicolas Boileau-Despréaux, elegant but uncreative poet, for his insistence on subjecting the imagination to the rule and regulation. Other cultivated genres were: burlesque (Paul Scarron), eloquence (Jacques-Bénigne Bossuet), psychological novel (Madame de La Fayette), didactic novel (François Fénelon), satirical prose (Jean de La Bruyère, François de la Rochefoucauld), epistolary literature (Jean-Louis Guez de Balzac, the Marquise de Sévigné), religious literature (Blaise Pascal), the fantastic novel (Cyrano de Bergerac) and the fairy tale (Charles Perrault).