Bantu languages

The Bantu languages are a group of languages spoken in Africa that constitute a subfamily of Niger-Congo languages. Bantu languages are spoken in southern Cameroon, Gabon, the Republic of the Congo, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Uganda, Kenya, Tanzania, Angola, Zambia, Malawi, Mozambique, Zimbabwe, Namibia, Botswana, and South Africa.

The word Bantu was first used by Wilhelm H. I. Bleek (1827-75) to mean "people" (*ba-ntu is a plural form, the singular would be *mu-ntu) as reflected in many of the languages in this group (see table 1). He is also responsible for the first classification of the group of languages following scientific criteria carried out between 1862 and 1869. He and later Carl Meinhof made comparative studies of the grammars of the Bantu languages.

Classification

Family languages

The Bantu language with the largest number of speakers is Swahili (G 40). The Bantu languages comprise a range that goes from purely tonal languages to those that totally dispense with tone with grammatical and/or semantic functions.

Other important Bantu languages include Lingala, Luganda, Kikongo (or Kongo) and Chewa in East and Central Africa and Shona, Ndebele (often considered a language but actually a dialect of Zulu), Setswana, Sesotho, Xhosa, Sepedi and Swazi in southern Africa.

Some of the languages are known without the class prefix (Chewa for Chichewa, Swahili for Kiswahili, Zulu for Isizulu, Xhosa for Isixhosa, etc.) while others vary (Setswana or Tswana, Sindebele or Ndebele, etc.). However, the stem form without the marker does not normally occur in these languages: in Botswana, for example, the inhabitants are Batswana, a person is a Motswana, and the language it is setswana.

Internal sorting

Guthrie Classification

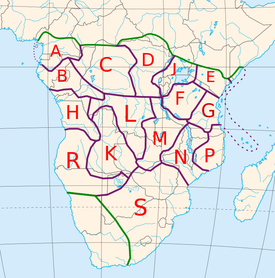

This language family has hundreds of members. They were classified by Guthrie in 1948 into groups according to geographic zones - A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H, J, K, L, M, N, P, R and S and then numbered within the cluster. (List of Bantu language names with synonyms ordered by Guthrie number.) Guthrie also reconstructed Proto-Bantu as the proto-language of this language family. Everything seems to point to the fact that the Bantu languages originated 3,000 years ago in eastern Nigeria and Cameroon, from where they expanded 2,000 years ago to the south and east of the African continent. The main groups according to Guthrie (1948) are the following (main languages are in italics):

- Protobantú

- Northwest Bantu or Bantu of the jungle

- A: South Cameroon, North Gabon and Equatorial Guinea, e.g. basea, fang, bubi.

- B: South Gabon, R. Congo and Equatorial Guinea, e.g. Balengue.

- C: R.D. Congo and R. Congo, e.g. lingala.

- South-central Bantu or Bantu de la saana

- D: Especially in R.D. Congo.

- E: In Kenya and Tanzania, e.g. kikuyu.

- F: In Tanzania, e.g. sukuma.

- G: In Tanzania and Comoros, e.g. suajili, gogo, comorense, mahorés.

- H: In Angola and the Congo, e.g. kikongo, kitubaKimbundu.

- J o Bantu de los Grandes Lagos (group added later): In Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi and close to the Great Lakes of Africa, e.g. luganda, kinyarwanda, kirundi, luhya, Nande, nkore.

- K: Mainly in Angola and Zambia, e.g. chokwe, ruKwangali

- L: In R.D. Congo and Zambia, e.g. Chiluba

- M: Zambia, Tanzania and R.D. Congo. The bemba is official in Zambia.

- N: In Malaui, Mozambique and Zambia, e.g. chichewa that is official in Malaui and the tumbuka.

- P: In Mozambique and Tanzania, e.g. makua, eChuwabo.

- R: Angola, Namibia, Botswana, e.g. umbundu, oshiwambo (dialectos kuanyama, ndonga), heir.

- S o South Bantu: South Africa, Botswana, Zimbabwe and Mozambique. It is divided into the following subgroups:

- Chopi

- Nguni: xhosa, Zulu, ndebele of the north, suazi, ndebele of the south

- shona: with various dialects like zezuru.

- Sotho-Tswana: setsuana, sesotho, sesotho sa leboa, lozi

- Tswa-Ronga: xiRonga, tsonga

- bandage

- Northwest Bantu or Bantu of the jungle

Modern Classification

Guthrie's classification was used for subsequent classifications, which consisted of subgroup reassignments and group divisions, in order to ensure that all subgroups are valid phylogenetic groups.

Common features

Phonology

The Bantu languages have been extensively studied phonologically and phonetically, and the historical phonology of the family is well known. The proto-Bantu has been reconstructed and there is a great consensus among the Bantuists as to the basic characteristics. Despite the enormous variety that the Bantu languages present, the phonological system of Proto-Bantu is surprisingly simple. The reconstructed consonant inventory lacks approximants and is given by:

bilabial Alveolar palatal ensure that Obstructants sorda ♪ ♪ *c ♪ Sonora ♪ ♪ * ♪ Nose ♪ ♪ *

The voiceless obstruents /*p, *t, *k/ appear to have been stops, while sounds designated as /*b, *d, *g/ could be plosives or as in many of its modern continuing descendants [β/w, ð/ɬ, ɣ]. The "palatals" designated as /*c, *ɟ/ could have been genuine palatal stops [c, ɟ] or possibly postalveolar affricates [ʧ, ʤ/ʒ] (In fact many Bantu languages have the evolutions /*c/ > /s/ and /*ɟ/ > /z/ which reinforce their interpretation as affricates.) This The Proto-Bantu consonantal system adequately accounts for later historical developments in Central Bantu, and the appearance of shared phonetic innovations is what allows internal groupings to be established with certainty. For some authors the previous system reconstructed by Greenberg, Guthrie and Meeusen is only ancestral to the Bantu of the savannah or Central Bantu. According to Stewart (2002) the northeastern Bantu and the central Bantu would be two branches derived from an ancestral proto-Bantu with a more complicated system:

bilabial Alveolar palatal ensure that Obstructants explosive ♪ ♪ *c ♪ implosive * * * * Nasal deaf ♪ ♪ ♪ (*GUEK) Sonic nasal ♪ ♪ * *

According to Stewart, there would have been a convergence of the second and third series /*mb, *nd, *ɲɟ, * ŋg/ > /*b, *d, *ɟ, *g/ and /*ɓ, *ɗ, *ʄ, *ɠ/ > /*b, *d, *ɟ, *g/. On the other hand, the last series would be the origin of the nasals /*mp, *nt, *ɲc, (*ŋk)/ > /*m, *n, *ɲ, (*ŋ)/.

The vowel system seems clear that it was made up of seven elements that could be grouped into three distinctive opening levels that some authors reconstruct as / *i, *ɪ, *e, *a, *o, *ʊ, *u/ and others such as /*i, *e, *ɛ, *a, *ɔ, *o, *u/.

The possible syllabic structures in Proto-Bantu were:

CV, CVV;V, N{displaystyle {mbox{CV, CVV;}qquad {mbox{V, N}}}

Where C: any consonant, V: any vowel, VV: long vowel, N: nasal consonant.

Grammar

| Person / Gente various Bantu languages | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Table 1: The root of each word appears highlighted in bold preceded by Class prefix. |

Bantu languages are agglutinative languages. The most prominent morphological feature of the Bantu languages is the extensive use of prefixes and infixes. Each name belongs to a class and each language can have around ten classes altogether, something similar to gender in European languages. The class is indicated by a prefix in the noun, as well as in the adjectives and verbs that agree with it. The plural is indicated by a prefix change (see Table 1).

The verb is conjugated based on prefixes. In Swahili, for example:

- Mtototo mdogo amekisoma

- 'The little boy has read it (the book)'.

Mtoto, 'child,' governs the adjectival prefix m- of mdogo, 'little' 39;, and the verbal subject prefix a-. This is followed by the present perfect tense -me- and the object marker -ki- that matches the implicit word kitabu, & #39;book. If we pluralize the subject ('children'), we get:

- Watoto wadogo wamekisoma

and by pluralizing the direct object ('books', vitabu) the resulting phrase is

- Watoto wadogo wamevisoma.

Verb

The typical structure of a verb form in many Bantu languages is:

(Pre)-Suj-(Neg)-(TG)-(AG)-(Obj)-R-VF{displaystyle {mbox{(Pre)-Suj-(Neg)-(TG)-(AG)-(Obj)-R-VF}},}

Where

- Prepre-initial prefix

- Suj, subject mark

- Neg, negative prefix (for negative sentences)

- TG, grammatical time

- AG, grammatical look

- Obj, object mark

- R, verbal root

- VF, final flexive vocal

Examples:

- mó-tu-téta-ya-mú-♪- Yeah. (Nande)

- Pre-Suj-Neg-AG-Obj-R-VF

- 'We didn't go and send him.'

- a-si-nge-fañ- Yeah. (Swahili)

- Suj-Neg-AG-R-VF

- '(he/she) wouldn't.'

Syntax

Most of the languages in this group form the sentence according to the basic scheme of SVO (subject - verb - object). They also use prepositions and typologically they are initial nucleus languages.

Lexical comparison

The reconstructed numerals for different Bantu language groups are:

| GLOSA | PROTO-TEKE-MBEDE | PROTO-MBOSHI-BUJA | PROTO-BANGI-TETELA | PROTO-KONGO-YAKA | PROTO-RUFIJI-RUVIMA | PROTO-BANTU NEED | PROTO-BANTÚ S | PROTO-BANTÚ SW | PROTO- BANTUS | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| '1' | *-m-(-si) | ♪-m-- | *-mwe | ♪ Let's go | -mo. | *-mwe / ♪-moi | *mwe | *-mwe/ ♪ Let's go | ♪ | ||

| '2' | *bwadi | *-bali | ♪ | ♪ | *-βeli | *-βiri | *(m-)b ratei | ♪ | *-bàd. | ||

| '3' | *-tatu | *--atu | ♪ | ♪ | *-ta devotedtu | *-tha devotedtu | *(m-tharu) | ♪ | *-tátě | ||

| '4' | ♪ | *-nai | *n | ♪ | *-n-e-e | *-nai | *(mu-)n transformation | *-n | ♪ | ||

| '5' | *-ta devotednu | *-tanu | *ta(about)no | *ta | *-cha wakeno * | *-tha childhood | *chanu | ♪ | ♪-tâ ♪ ♪-câ ¦ | ||

| '6' | *-sjaminu | *- -amano | samanu | * | *5+1 | *-tan-atu | *5+1 / ♪ I-pu | *5+1 | |||

| '7' | *aa devotedm-bwadi | * *ambali | *sam-badi | *-sambwadi | *5+2 | ♪ | *5+2 / *()i)-khomb- | *5+2 | *-câ infon-bàdray | ||

| '8' | *-na tipna | *-nanai/ ♪ | *na(turning)nai | *na feltna | *5+3 / *-na tipne | -*na memorial | *5+3 | *5+3 / *-nan transformation | *-na tipàì | ||

| '9' | *-bwa | *i-bwa | *-bwa | *-bwa | *5+4 | *ke wandernaa | *5+4 | *5+4 | |||

| '10' | *-ku childhood | * *umi | *ku feltmi | *-ku childhood | *i-kumi | *kumi | *-kumi/ *omurożgo | *kifies tom |

History

Black South Africans were sometimes officially referred to as Bantu by the apartheid regime, so the term sintu is now preferred there to refer to this language group; si- is a prefix used, among other things, for the name of many southern Bantu languages (derived from Proto-Bantu *ci-)

Contenido relacionado

Indonesian culture

Seraiki

Ethnography of Trinidad and Tobago