Ballista

The ballista or ballista (from Latin: ballista, from Greek: βαλλιστής, ballistra, from βάλλειν bállein, 'throw, throw'') is a siege weapon that hurled a projectile, usually an arrow or a stone, at a target at distances of more than 100 meters. Used in Europe from classical antiquity until the advent of the cannon in the 15th century, it was similar in appearance and mechanism to the a crossbow, but of a larger size. This siege weapon was developed around 400 BC. C. by the ruler of Syracuse Dionysius I of Syracuse from the oxybeles and the gastrafetes, similar in appearance and mechanism to those of a crossbow, but much larger. Early versions projected heavy darts or spherical stone projectiles of various sizes for siege warfare. It evolved into a smaller precision weapon, the scorpio, and possibly the polybolos.

Design

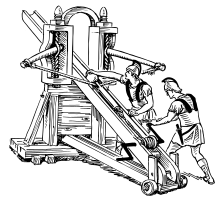

The ballista was usually made of wood, though it could have parts made of or at least clad in metal, and used string, animal sinew, or horsehair as tensioners. Developed from earlier Classical Greek era weapons, it was based on different mechanics and used two levers that delivered potential energy through ropes or sinew woven into twisted skeins. The system was based on the torsion of an elastic material, instead of a tension blow like the one used in a bow, thus improving its effectiveness. This allowed him to throw large rocks or sharp-tipped wooden bolts. The larger calibers could hit targets more than 150 meters away, making them important siege engines.

Due to its size, it had to be supported on a tripod and was handled by several men in charge of placing the projectiles, tightening the machine by the torsion mechanism and finally releasing the projectile. If the maneuver was done correctly, the projectile would be fired great distances. It was mainly used in sieges, as once mounted it was difficult to aim at moving targets. However, on certain occasions wheels were incorporated into the ballista support to be able to change it without having to disassemble it.

Origin

The term is used in a confusing way: at first it is understood as a catapult to the weapon that launches arrows or spears (also called oxybolos and dorybolos), and ballista to the stone-throwing device (also called lithobolos and petrobolos), more powerful than the previous one. At some point in the IV century, these definitions are reversed and ballista comes to define the least powerful spear or arrow-throwing machine.

The term catapult is the oldest used to designate the first heavy weapons. Its etymology, from the Greek καταπέλτης katapéltēs, comes from the Greek words katá (downwards) and pelte (light shield). the term designates a machine capable of breaking shields in the downward trajectory of its missiles. Subsequently, this word will designate only a special type of these weapons. It is in the year 399 B.C. C. when the tyrant of Syracuse, Dionisio el Viejo, ordered to prepare new mechanical weapons to defend the city from the siege of Carthage, which were reported for the first time. Among them is the gastraphetes, ancestor of the crossbow or the oxybeles. It is a kind of large crossbow placed on a tripod, which launched large arrows (600 to 800 grams), which could cross a line of men.

Ancient Greece

The first ballistae in Ancient Greece were developed from two weapons called oxybeles and gastrafetas. The gastraphetes ('navel bow') was a hand crossbow. It had a compound nose and was extended by holding the front end of the weapon against the ground while the end of a sliding mechanism was placed against the stomach. The operator would then walk forward to cock the gun while a ratchet prevented it from firing during loading. This produced a weapon that, it was claimed, could be operated by a person of average strength but had a power that allowed it to be used successfully against armored troops. The oxybeles was a larger and heavier construction that used a winch and was mounted on a tripod. It had a lower rate of fire and was used as a siege engine.

With the invention of torsion spring beam technology, the first leaf springs were built. The advantage of this new technology was the fast relaxation time of this system. Thus, it was possible to fire lighter shells with higher velocities at a longer distance. By contrast, the comparatively slow relaxation time of a tension machine such as the oxybeles meant that much less energy could be transferred to light shells, limiting the weapon's effective range.

The earliest form of crossbow is believed to have been developed by Dionysus of Syracuse, around 400 BC. c.

The Greek ballista was a siege weapon. All non-wooden components were transported on the baggage train. It would be assembled from local wood, if necessary. Some were placed inside large, armored, mobile siege towers or even on the edge of a battlefield. Despite all the tactical advantages offered, it was only under Philip II of Macedon, and even more so under his son Alexander, that the ballista began to develop and gain recognition as a siege machine and field artillery. Historical accounts, for example, cite that Philip II employed a group of engineers within his army to design and build catapults for his military campaigns. It is even claimed that it was Philip II with his team of engineers who later invented the ballista. Dionysus's device, which was nothing more than a large slingshot, was further refined by Alexander, whose own team of engineers introduced innovations such as the idea of using springs made of tight coils of string instead of a bow to achieve more energy and power when launching projectiles. Polybius reported the use of smaller, more portable crossbows, called scorpions, during the Second Punic War.

The ballistas could be easily modified to fire shaft and spherical projectiles, allowing their operators to easily adapt to prevailing battlefield situations in real time.

As the role of artillery on the battlefield became more sophisticated, a universal joint (invented just for this role) was integrated into the ballista mount, allowing operators to alter the trajectory and the direction of firing of the ballista as necessary without long disassembly of the machine.

Roman Empire

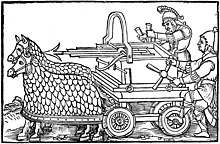

It was a fundamental weapon of war during the Roman Empire, along with the catapult or the onager. Each legion, depending on the historical moment, could have several ballistas in the corps or units named as ballistarii. There were also carroballistae or carroballista: units made up of a horse-drawn cart with a mounted ballista. It was of great importance until in the late period it was displaced by the use of the onager. Although the Latin sources speak of huge ballistas. It is not certain if it was part of the propaganda, but it is certain that they at least reached eight meters in height.

It was used just before the start of the empire by Julius Caesar during his conquest of Gaul and invasions of Britain. Both attempted invasions of Britain and at the Battle of Alesia, he recorded the use of the ballista in his own commentarii (diary), De bello Gallico. There is also evidence that they were used in the battles of Bedriacum, in the siege of Rhodes or during the siege of Jerusalem.

The Roman engineer Marco Vitruvio recorded in his work De architectura the use of war machines such as the ballista and his experience in the Roman army, as well as the adaptation of the Greek versions. This work, the tenth book on machines, devotes chapter XVI to the construction of ballistae, the XVII to the proportions of crossbows and chapter XVIII to the way of firing catapults and crossbows. As far as ballistas are concerned, his main contribution is the incorporation of a new type of clamp that manages to increase the size of the nerve of the spring, increasing its power.

Dexo explained the construction, parts and proportions of the catapults. The crossbows are several and different, though all for one effect itself: for some operate with levers and axes, others with polyspastes, others with organs, and some also with eardrums: but no crossbow is built but with the due proportion to the stone that should be thrown: for what reason it is not for all its construction, but only for the practical ones in Arithmetic, at least in numbering and multiplication. For the holes are made in the capitals through which the hair maromas are passed, mainly of a woman, or of a nerve, which are given in resistance to the gravity of the stone that is to throw away the crossbow; as in the catapults it is taken from the length of the dart. But so that even those who did not know Geometry or Arithmetic can build them, and in time of hostility they are not pregnant in calculations, I will put what I have experienced myself in practice, and what my teachers taught me in part; reducing the notes of the Greek pesos to ours.Marco Vitruvio, De architectura. Book I. Chapter XVI: From the construction of the crossbows. Page 256.

Early Roman crossbows were made of wood and held together with iron plates around the frames and iron nails in the bracket. The main support had a slider at the top, where stone in the form of bolaños or other projectiles were loaded. Attached to this at the rear were a pair of vises and a claw, used to retrieve the bowstring to the starting position for cocking the shot. A slider passed through the field frames of the weapon, in which were the torsion springs (usually animal tendon), which twisted around the bow arms, which in turn were attached to the bowstring. bow. In this way, when the bowstring was pulled back with the spring winches already taut, the energy needed to fire the projectiles was stored. The Roman writer Lucilius described them as weapons that could throw stones ranging from one kilo to 30 kilos generally, although projectiles of more than 70 kilograms have been found. Using smaller stones would imply a greater speed in the offensive.

The ballista was a highly accurate weapon, but the design compromised range for accuracy. Catapults sacrificed this precision for the range and weight of the projectile, reaching more than 100 kilograms.

A psychological weapon as well

Its value -like the rest of the siege weapons- was not only for its capacity for personal or material destruction, but also for the moral or psychological damage to the defensive troops. Not only because of the impact of the projectile at a distance, but because of the sound they generated. To make the ballista appear more impressive during battle, decorations were added to make it more monumental, and sometimes even fake weapons were created to further fear the enemy.

Thus, seeking precisely a demoralizing effect, the Carthaginian general Hannibal in command of a fleet at the service of the Prussian king of Bithinia, in 184 B.C. In a naval battle, he used crossbows to launch clay jars filled with poisonous snakes against the fleet of King Eumenes II of Pergamon, an ally of Rome.

Notable archaeological remains

- The Roman ship of Mahdia. In 1907 he appeared in Tunisia, near the city of Mahdía, a Roman ship four kilometres from the coast and submerged 40 meters. Inside it was found as part of a gear, a dented wheel of ten centimeters and with teeth along the middle of the wheel, two other dented wheels of smaller dimensions and one Modiolus: a wheel of about fifteen centimeters in diameter with perforations at 30o perimeter. All this was part of mechanical mechanisms to elevate and aim the ballists. It is believed that the ship carried the spoils of the site of Athens by Sila in 86 a. C.

- Hatra ballist. In 1972, in the city of Hatra, Iraq, several fragments of a ballist were found. They were located in one of the gates of the city until during a siege the entrance was demolished, burying the machine. Parts found Modiolus bronze and slats, wooden remains or 2 millimeter bronze plates that served as protection against fire. It is estimated that its size was 240 cm wide, 84 cm high and 45 cm thick.

Middle Ages

With the decline of the Roman Empire, the resources to build and maintain these complex machines became very scarce, so the crossbow was initially supplanted by the simpler and cheaper onager and the more efficient musket.

Although the weapon continued to be used in the Middle Ages, it faded from popular use with the advent of the trebuchet and mangonel in siege warfare.

While not a direct descendant mechanically, the concept and name continue as crossbows arbalistas (arcus 'bow' + crossbow).