Aviation history

The history of aviation dates back to the day when prehistoric humans stopped to observe the flight of birds and other flying animals. The desire to fly has been present in humanity for centuries, and throughout human history there is evidence of attempts to fly that have ended badly.

Many people said that flying was impossible for the capabilities of a human being. But even so, the desire existed and various civilizations told stories of people endowed with divine powers who could fly. The best known example is the legend of Icarus and Daedalus, who, being prisoners on the island of Minos, built themselves wings with feathers and wax in order to escape. Icarus got too close to the Sun and the wax on his wings began to melt, causing him to plunge into the sea and die. This legend was a warning about attempts to reach heaven, similar to the story of the Tower of Babel in the Bible, and exemplifies man's age-old desire to fly.

The modern history of aviation is complex. For centuries there were timid attempts to take flight, most of them failing, but since the 18th century, humans began to experiment with hot air balloons that managed to rise into the air, but had the drawback of not being able to be controlled. This problem was already overcome in the 19th century with the construction of the first airships, which did allow their control. At the beginning of that same century, many investigated the flight with gliders, machines capable of sustaining controlled flight for some time, and the first airplanes equipped with motors also began to be built, but which, even when propelled by external aid, barely managed. take off and travel a few meters. It was not until the beginning of the 20th century that the first successful flights took place. On December 17, 1903, the Wright brothers became the first to fly in a controlled airplane, however some claim that this honor belongs to Alberto Santos Dumont, who made his flight on September 13, 1906.

From then on, the improvements continued, and each time substantial improvements were achieved that helped develop aviation to the way we know it today. Aircraft designers continue to strive to continuously improve their capabilities and characteristics, such as their autonomy, speed, load capacity, ease of maneuvering or safety, among other details. Aircraft have started to be built with increasingly less dense and more resistant materials. Previously they were made of wood, currently the vast majority of aircraft use aluminum and composite materials as the main raw materials in their production. Recently, computers have contributed a lot in the development of new aircraft.

Antiquity-18th century: First designs and theories

It is known that around the year 400 B.C. C., Arquitas de Taranto, a scholar of Ancient Greece, built a wooden artifact that he himself baptized with the name of "Peristera" (Greek: Περιστέρα, "Dove"), which had the shape of a bird and was capable of flying up to 180 meters high. He used a jet of air to take flight, but there is no record of what produced that jet. The flying object was tied by means of ropes that allowed it to carry out a controlled flight until the jet of air ended. This wooden artifact was probably the first flying machine capable of moving under its own power.

The Kong Ming lantern, the forerunner of the hot air balloon, has been known in China since ancient times. Their invention is attributed to General Zhuge Liang, and they were used to scare enemy troops. About the year 300 B.C. C. the Chinese invented the kite, which is considered a type of glider, and developed techniques to make it fly in the air. Centuries later, in the year 559 there are documented flights of human beings using comets. Emperor Gao Yang experimented on prisoners, including Yuan Huangtou, the son of the previous emperor, Yuan Lang. He ordered them to jump from the top of a tower, and Yuan Huangtou glided past the city's barriers, though he would be executed soon after.

In the year 852, the Andalusian Abbas Ibn Firnás, jumped from the minaret of the Mosque of Córdoba with a huge canvas to cushion his fall, suffering minor injuries, but going down in history as the precursor of modern parachutes. In 875, at the age of 65, Ibn Firnás had wooden wings covered with silk cloth that he had decorated with raptor feathers made. With them he launched himself from the top of a hill, and managed to stay in the air for a short time, although there are stories that say that he flew for more than ten minutes. The landing was very violent and Abbas Ibn Firnas broke both legs, but he considered the experience a success, as did the large crowd of people who watched.

This flight served as the inspiration for Eilmer of Malmesbury, a Benedictine monk, who more than a century later, around the year 1010, traveled more than 200 meters in the air, on a device similar to that of Abbas Ibn Firnás.

In 1290, Roger Bacon, an English monk, wrote that air, like water, had some characteristics of solids. Bacon studied Archimedean ideas related to the density of the elements, and came to the conclusion that if people could build a machine with the right characteristics, the air could support that machine, just as the sea supports a ship.

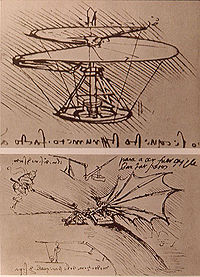

Most likely, the Italian artist and inventor Leonardo da Vinci was the first person to seriously dedicate himself to designing a machine capable of flying. Leonardo designed gliders and ornithopters, which used the same mechanisms used by birds to fly, through a constant movement of the wings up and down. However, he never actually built such machines, but his designs were preserved, and subsequently, already in the XIX century and XX, one of the gliders designed by Leonardo da Vinci was considered noteworthy. In a recent study, a prototype based on the design of that same glider was created, and indeed, the aircraft was capable of flight. However, when interpreting the glider design, some modern ideas related to aerodynamics were applied. Even so, this design is considered the first serious sketch of an aircraft.

18th-19th century: Aircraft that are lighter than air

According to chronicles of the time, the first successful flight of a hot air balloon was thanks to Father Bartolomeu Lourenço de Gusmão, a Portuguese born in Brazil in colonial times, who managed to raise the flight of an aerostat, which he would call passarola, on August 8, 1709 at the court of Juan V of Portugal, in Lisbon. In the demonstration, the passarola rose some ten feet above the ground, impressive to observers, and earning it the nickname Flying Father. No detailed descriptions of the event have survived, probably because were destroyed by the inquisition, but some fanciful designs of the eccentric aircraft appeared in the Viennese newspaper Wienerische Diarium of 1709. According to a chronicle in that newspaper, the apparatus consisted of a thick paper balloon, which inside it contained a bowl of fire, and it managed to rise more than twenty feet. However, the passarola did not influence the aviation developments that would occur later.

The first published aviation study was Emanuel Swedenborg's Sketch of a Machine for Flying in the Air, published in 1716. This sketch of a flying machine consisted of a fuselage and two large wings that would move along the horizontal axis of the aircraft, generating the necessary thrust for its lift in the air. Swedenborg knew that his machine would never fly, but he said that the problems that existed in his design would be solved in the future. His words were:

It seems easier to talk about a machine capable of flying, than to build one capable of lifting the flight, because this requires a greater amount of force than man is capable of generating, and less weight than that of a human body. Mechanical science may help, like a strong spiral bar. If these requirements are met, perhaps one day we will know better how to use this design and thus make the necessary improvements to try to fulfill what we currently do, we can hardly describe. We have sufficient evidence and examples in nature that tell us that flying without danger is possible, although when the first attempts are made, we will possibly have to pay for lack of experience, with an arm or leg (brada).

The strong spiral bar described by Swedenborg is what is now known as a helix. He knew that lift and the way to generate that lift would be essential for the creation of a device capable of flying by its own means.

The first recorded human flight was made in Paris on October 15, 1783, in a tethered balloon. Two months later, the doctor Jean-François Pilâtre de Rozier and the nobleman François Laurent d'Arlandes, made the first free flight in a machine created by man. They managed to fly for 25 minutes, covering eight kilometers in a balloon air heater, invented by the Montgolfier brothers, two paper manufacturers. The air inside the balloon's air chamber was heated by a wooden fire. The balloon had the disadvantage that it was uncontrollable, it flew where the wind took it. This balloon, being quite heavy, reached a maximum height of just 26 meters. The Montgolfier brothers went on to make other balloons, achieving several successful flights, causing balloon flight experimentation to spread across Europe throughout the century XVIII. The balloons allowed the deepening of knowledge about the relationship between altitude and atmosphere. Even Napoleon Bonaparte planned to use balloons in a possible French invasion of England.

In November 1792, the rehearsals carried out by a group of artillerymen from the Royal College of Artillery in the Alcazar of Segovia and later before King Carlos IV of Spain of the flight of a hot air balloon, all of them directed by Louis Proust; They were the first made in the world in the military aspect.

Also in Spain, Diego Marín Aguilera was the first man reported to have flown with a device that weighed more than air. On the night of May 15, 1793, Diego Marín Aguilera made a 360-meter flight in Coruña del Conde, Burgos province with an iron artifact and bird feathers, controlled by the pilot himself, who managed to reach "five to six varas” high above the starting point until landing on the other side of the river after having traveled a route of “431 Castilian varas” (about 360 meters). The reason for the rapid landing was the breakage of one of the bolts that moved the wings. In the morning, when the neighbors found out what happened on that emotional night in May, they mocked their neighbor Marín, believing him crazy, and they set fire to the feathered device as something diabolical.

Other inventors, such as the Frenchman Jacques Charles, replaced hot air with hydrogen, which is a gas that is lighter than air. But in the same way, the balloons still could not be directed, and only the altitude was controllable by the aviators.

In the 19th century, in 1852, the French engineer Henri Giffard invented the airship, which is a lighter machine than the air, and differs from the balloon in that its direction could be controlled through the use of rudders and engines. The first controlled flight of an airship took place on September 24 of that same year in France, controlled by the Giffard himself, managing to travel 24 kilometers, at a speed of 8 km/h using a small steam engine. Throughout the late 19th century and into the first decades of the XX, the airship was a trusted method of transportation.

19th century: Gliders

With the invention of the balloon and the dirigible, inventors began trying to create a heavier-than-air machine that was capable of flying under its own power.

First of all, gliders appeared, machines capable of sustaining controlled flight for some time. In 1799, George Cayley, an English inventor, designed a relatively modern glider, which had a tail to control it, and a place where the pilot could be placed, below the center of gravity of the apparatus, thus giving stability to the aircraft. Cayley built a prototype, which made its first unmanned flights in 1804. Over the next five decades, he worked on its prototype, during which time Cayley deduced many of the basic laws of aerodynamics. In 1853, one of Cayley's assistants made a short flight in a glider at Brompton, England. George Cayley is considered the founder of the physical science of aerodynamics, having been the first person to describe an engine-powered fixed-wing aircraft.

In 1856 the Frenchman Jean-Marie Le Bris made the first flight that glided higher than his takeoff point, thanks to his glider, the L'Albatros artificiel, which, for take off, it was dragged by horses on the beach. According to him, he reached a height of 100 meters and covered a distance of 200.

In 1866, a Polish peasant and carpenter named Jan Wnęk built and flew a controllable glider. Wnęk was illiterate and self-taught, and all the knowledge and deductions about gliders he obtained by observing the flight of birds and thanks to his skills. Jan Wnęk was firmly strapped to his glider across the chest and hips and controlled it with wing rolls. To test it, he jumped from the tower of the Odporyszów church, 45 meters high, which in turn is located on a 50-meter hill, making the relative height 95 meters to the valley. He made several flights with the public between 1866 and 1869, especially during religious festivals, carnivals and New Year's celebrations, but Jan Wnęk's deeds were hardly recorded and had no impact on the progress of aviation.

At this time, Frank Wenham tried to build a series of gliders, but they were unsuccessful. In his efforts, he discovers that most of a bird's lift seemed to be generated at the front, and Wenham deduced that thin, long, fixed wings, similar to today's airplane wings, would be more efficient than wings. similar to those of birds or bats. His work was presented to the newly formed Royal Aeronautical Society of Great Britain in 1866, and Wenham decided to test his ideas by building the world's first wind tunnel in 1871. Society members made use of the tunnel and were surprised and delighted. with the result: fixed wings generated significantly more lift than scientists had anticipated. This experiment clearly demonstrated that the construction of heavier-than-air machines was possible, the problem was how to generate the necessary thrust to move the apparatus forward, since they had verified that fixed-wing aircraft required a constant flow of air passing by the wings, and it was still necessary to be able to control the aircraft in flight.

In 1874, Félix du Temple built a glider made of aluminum in Brest (France), which he called Monoplane. It had a wingspan of 13 meters and a weight of 80 kilograms without counting the pilot, as well as being self-propelled. He carried out several tests, and apparently managed to take off thanks to a ramp, and then achieve a safe landing, making the first self-propelled flight in history, even if it was for a short time and the distance traveled was short.

The 1880s were a time of intense study, characterized by the gentleman scientists, scientists who had the necessary resources to conduct independent research without having to rely on outside funding, who did most of the research. part of the research in the field of aeronautics until the turn of the XX century. A large number of advances were made that would make the first practical gliders possible. Three names in particular brought great insights: Otto Lilienthal, Percy Pilcher and Octave Chanute.

One of the first modern gliders was built in the United States by John Joseph Montgomery, who flew his machine on August 28, 1883, in a controlled flight. But it took a long time for Montgomery's work to be acquaintances. Another glider was built by Wilhelm Kress in 1877 in Vienna.

The German Otto Lilienthal continued the work of Frank Wenham, publishing his research in 1889. Lilienthal also manufactured a series of gliders, and by 1891 was able to make sustained flight over 25 meters, improving on earlier attempts that featured unstable results. The German rigorously documented his work, even with photographs, and for that reason, he is one of the best-known aviation pioneers. He also promoted the jump before you take flight idea, suggesting that researchers should start with gliders and then try to work on projects to develop an aircraft, rather than designing such an aircraft directly on paper and wait for that layout to work.

Lilienthal made several successful flights until 1896, the year in which he died in a plane crash on October 9, caused by a sudden crosswind, which broke a wing of his aircraft in mid-flight, causing it to fall from a height of 17 meters. For all these reasons, Lilienthal is considered the first person to carry out a controlled gliding flight, in which the pilot controlled the aircraft. His last words before he died the next day were: "Sacrifices must be made."

At the time, Lilienthal was working on finding suitable small engines to equip his aircraft, with the idea of creating a heavier-than-air prototype capable of taking flight under its own power.

Octave Chanute continued Lilienthal's work in the area of gliders. He created several prototypes and included improvements to his own aircraft. In the summer of 1896, he made several flights on his gliders at Miller Beach, Indiana, United States, and decided that the best of them all was a biplane. Like Otto Lilienthal, Chanute documented his work in detail, and also photographed his machines and experiments.During his research, he spent part of his time corresponding by correspondence with people who had similar interests, including Percy Pilcher. Chanute was particularly interested in solving the problem of how to provide stability to the aircraft when it was in flight. This stability was achieved naturally in birds, but had to be done manually in the case of humans. Among the problems related to the stability of the biplane in flight, the most disconcerting was the longitudinal stability, since the angle of attack of the wing caused the center of pressure of the aircraft to increase and caused the angle of the biplane to increase even more. more, and you will lose.

19th century: Aircraft

In the 19th century some attempts were made to produce an aircraft that took off under its own power. But most of them were shoddy, built by people interested in aviation but not knowledgeable about the problems Lilienthal and Chanute dealt with.

In 1843, William Henson, an English inventor, registered the first patent for an aircraft equipped with engines, propellers, and a fixed wing, which is now known as an airplane. But the prototype built based on Henson's designs did not perform well, and he gave up on his project. In 1848, his friend John Stringfellow built a small airship based on Henson's designs, which was successful in certain respects, being able to take off by its own means, but it did so without a pilot, and it could only fly for two or three seconds.

In 1878, the Peruvian engineer Pedro Ruiz Gallo presented his work General studies of aerial navigation and resolution of this important problem where he explained the design of an "ornithopter". Ruiz Gallo would die in 1880 during the War of the Pacific.

In 1890, Clément Ader, a French engineer, built an airplane he called Éole, equipped with a steam engine. Ader managed to take off at Éole, but was unable to control the aircraft, and was only able to travel about 50 meters in the air. Even so, he considered the results satisfactory, and considered building a larger airship, the construction of which took five years of his life. But unfortunately, his new plane, called Plane III, was too heavy and he was never able to take off.

In 1884 the Russian Aleksandr Mozhaiski designed and created a monoplane with which he managed to take off thanks to a steam engine and travel a distance of between 20 and 30 meters.

At that time, Hiram Stevens Maxim, a British-born American, studied a series of designs in England, and built an aircraft of monstrous dimensions by the standards of the time. It was a 3,175 kg biplane with a 32-meter wingspan, equipped with two steam engines, each capable of generating 180 hp. Maxim built the aircraft to study the basic problems of aerodynamics and power. He observed that the device, without equipment that would help to obtain its control, would be unsafe and dangerous at any altitude, so he built a special runway, 550 meters long, where he placed some rails on which the plane was located to carry out tests. The first tests were carried out in search of problems, and from July 31, 1894 he began to increase the power of the engines in each test, lining up the apparatus on the runway. The first two were reasonably successful, the device managed to "jump" on the rails for a few seconds, but did not fly. In the third test, the crew applied maximum power to the plane's engines, reaching 68 km/h, and after traveling 180 meters there was so much lift that the plane went off the rails, managing to take off and fly traveling 60 meters. at which time the aircraft hit the ground. Maxim only returned to further testing in the 1900s, using gasoline engines and smaller aircraft.

Another aviation pioneer was Samuel Pierpont Langley, an American scientist who, after a successful career in astronomy, began a serious study of aerodynamics at what is now the University of Pittsburgh in the United States. In 1891, Langley published Experiments in Aerodynamics ( Experiments in Aerodynamics ), where he detailed his research, and it is from there that he devoted himself to designing and building aircraft based on his ideas. On May 6, 1896, a prototype built by him made its first successful flight. The name of the aircraft was Aerodrome No.5. The plane traveled approximately 1,000 meters at a speed of 40 km/h. On November 28 of the same year, he made another successful flight, with the Aerodrome No.6 device, which managed to successfully travel 1460 meters, but took off without crew members.

After the successes of these flight tests, Langley decided to build an airplane that would be capable of being flown by one person, so he began looking for people willing to invest in his new machine. It is then that the United States government subsidized him with fifty thousand dollars, thanks to the interest aroused by the idea of having a device that would serve as an aerial military observer, since the Spanish-American War was beginning at that time. Langley then built his Aerodrome A, and went on to carry out tests on an identical version but one quarter the size of the original model, and without crew members. The prototype flew twice on July 18, 1901, successfully making a few more takeoffs until 1903.

With the basic design of the aircraft apparently approved in the tests carried out, Langley accredited that the Aerodrome A was ready to be tested with a crew member on board. He then began to search for a suitable engine, and hired Stephen Balzser to build it. Langley was disappointed to see the engine put out just 8bhp of power, instead of the 12bhp he had expected. A Langley assistant, Charles M. Manly, redesigned the engine, transforming it into a five-cylinder, water-cooled engine capable of generating 52 bhp and 950 rpm, with a weight of 57 kg.

On October 7 and December 8, 1903, Langley, at the controls of Aerodrome A, attempted to get his plane off the ground. He carried out his attempts on a ship on the Potomac River, and used a catapult to provide the necessary thrust for takeoff. But unfortunately, the plane was very fragile, and in both attempts the plane ended up hitting the water right after takeoff. In addition to that, the plane did not have longitudinal control or landing gear, and therefore had to make takeoff attempts over the river. Another problem was that the funds available to him were running out, so he tried to get more, but his efforts failed.

For all the work carried out within the world of aviation, Langley was recognized by the Smithsonian Institution, an educational institution located in Washington D.C., as the inventor of the airplane, thanks to the fact that Glenn Hammond Curtiss later made several modifications at Langley's Aerodrome A in the 1910s, and would get airborne.

Meanwhile, in the UK, Percy Pilcher nearly became the first person to take flight in an airplane. Pilcher built several gliders: The Bat (El Murciélago), The Beetle (El Escarabajo), The Gull (La Gaviota) and The Hawk (El Halcón). He managed to take flight on all of them, succeeding in his attempts. In 1899 he built a prototype of a steam-powered airplane, but unfortunately Pilcher died in a plane crash with one of his gliders, without having tested his prototype. His works remained hidden for years, and only a long time later, aroused interest in the scientific community. More recent studies indicated that his prototype would have been capable of taking flight under its own power with a crew member on board.

Another name worth noting is that of Gustave Whitehead, whose first flight has been documented on August 14, 1901 in Connecticut (United States), the day he managed to fly with his model Number 21 three times. The information was reported in the Bridgeport Herald, New York Herald and the Boston Transcript, It is said that the longest flight managed to cover more than 2,500 meters at an altitude of 60 meters, being greater than the mark reached by the Wright brothers two years later.

Months later, in January 1902, he managed to fly 10 kilometers over Long Island in his model Number 22. But before that, some witnesses confirm a 1 km flight around the year 1899. Both the model Number 21 and Number 22 were single-seaters, the first one powered by an engine 15 CV and the second with a 30 CV engine. The engine accelerated the front wheels to gain takeoff speed, and the pilot shifted power to the propellers. In this way, the necessary catapult mechanism in the Wright brothers' model was avoided.

The plans of Whitehead's models have been preserved and in 1937, Stella Randolph compiled his work in The Lost Flights of Gustave Whitehead. Recognition of Gustave Whitehead would only come from that time.

1900-1914: The first flights in a heavier-than-air aircraft

The Wright Brothers

During the 1890s, brothers Wilbur and Orville Wright became interested in aviation, especially with the idea of building and flying a heavier-than-air aircraft that could take off under its own power. At that time, both managed a bicycle factory in Dayton, Ohio, United States, and began to read and study aviation-related books and documents with great interest. Following Lilienthal's advice, in 1899 they began manufacturing gliders. At the end of the century, they began to carry out their first successful flights with their prototypes, in Kitty Hawk (North Carolina), a place chosen because in that area they could find constant winds, which also blew in the same direction, thus facilitating the glider flights. In addition to that, the area had a flat ground, which made landings easier.

After several tests and glider flights, the Wrights decided in 1902 to build a heavier-than-air aircraft. They became the first team of designers to carry out serious tests to try to solve aerodynamic, control and power problems, which affected all airplanes manufactured at that time. For a successful flight, engine power and aircraft control would be essential, and at the same time the aircraft needed to be well controlled. The tests were difficult, but the Wrights were persevering. At the same time, they built an engine with the desired power and solved flight control problems through a technique called roll, rarely used in aviation history but which worked at the low speeds at which the plane would fly.

The plane that the Wright brothers made was a biplane that they called Flyer (Flyer ). The pilot remained lying on the lower wing of the plane, while the engine was located to the right of it, and rotated two propellers located between the wings. The roll technique consisted of ropes attached to the wingtips, which the pilot could pull or release, allowing the aircraft to rotate through the longitudinal and vertical axis, allowing the pilot to be in control of the aircraft. The Flyer was the first aircraft recorded in the history of aviation, endowed with longitudinal and vertical maneuverability, excluding Lilienthal's gliders, where control was carried out through the force of the crew member himself.

On December 17, 1903, just months after Langley's unsuccessful tests, Orville Wright became the first person to fly a self-propelled heavier-than-air aircraft, though not without controversies. The flight happened at Kitty Hawk. The brothers used rails to keep the device on its way, and a catapult to propel it. The plane gained altitude at the end of the run over the rails, covering 37 meters at an average speed of 48 km/h during the 12-second flight. That same day they carried out three flights, which were witnessed by four lifeguards and a child from the area, making these the first public and documented flights. In a fourth flight the same day, Wilbur Wright managed to cover 260 meters in 59 seconds. Some Ohio state newspapers, including the Cincinnati Enquirer and the Dayton Daily News They published the news of the event the following day.

The Wright brothers made several public flights (more than 105) between 1904 and 1905, this time in Dayton, Ohio, inviting friends and neighbors. In 1904, a crowd of journalists gathered to witness one of the Wrights' flights, but because of technical problems with their plane, which they could not correct in two days, Orville and Wilbur were ridiculed by the media, going on to receive little attention, with the exception of the Ohio press. Several journalists from that state witnessed various of his flights, including the first circular flight in the world, and a new distance record, since during an attempt on October 5, 1905, they traveled 39 kilometers in 40 minutes. Starting in 1908, the Wright brothers' airplanes no longer needed the catapult to take flight.

On November 7, 1910, they made the world's first commercial flight. This flight, made between Dayton and Columbus (Ohio), lasted one hour and two minutes, covering 100 kilometers and breaking a new speed record, reaching 97 km/h.

Alberto Santos Dumont

Brazilian Alberto Santos Dumont was fascinated by machines. In 1891 he moved with his father to Paris, where he was amazed by the world of aviation. He made his first flights as a passenger in a balloon and later created his own balloon, the Brésil (Brazil in French). Santos Dumont also created a series of airship models, some of which were successfully flown but others not. The deeds carried out by Santos Dumont in Paris made him a famous person in that city.

On September 13, 1906, Santos Dumont made a public flight in Paris, in his famous plane, the 14-bis. This device used the same warping system used in the Wright brothers' aircraft and managed to travel a distance of 221 meters. The 14-bis, unlike the Wrights' Flyer, did not need rails, catapults or wind to take flight and, as it had a lot of media coverage at the time, the flight is considered by some people to be the first successful flight of an aircraft. When this flight was made, little or nothing was known about the Wright brothers, which is why the international press considered Santos Dumont's 14-bis as the first aircraft capable of taking off under its own power.

Santos Dumont, after 14-bis, would invent the first ultralight, the Demoiselle, which was the last device he would develop. He also made important advances related to the control of the plane in flight and the ailerons of his aircraft.

Controversy between the Wright brothers and Alberto Santos Dumont

There is great controversy regarding the realization of the first flight. Generally there are two opinions, those who consider the Wright brothers (specifically Orville Wright) to be the author of this feat and those who consider Alberto Santos Dumont. The latter made the flight of 14-bis in Paris, the first of an airplane in the history of aviation that is achieved without external artifice and that is registered and published. Specialists allege the use of rails and catapults in the takeoff tests of the Wright brothers, and the testimony of the flight of 14-bis in Paris by aviators and aviation authorities.

In this regard, the Wright brothers did not perform many public flights, as they intended to carry out their flights alone or with few witnesses present, although they had attempted to carry out demonstrations for the armed forces of the United States, France, the United Kingdom and Germany, all without success, with the intention of avoiding the theft of information by other aviators, and seeking to perfect the device enough to obtain the patent for his plane (ironically, Santos Dumont put all his inventions in the public domain).

Some aviation specialists credit the Wright brothers as the first to fly a heavier-than-air aircraft. Despite the lack of reports from aviators and aviation organizations, the same specialists also point to the fact that, through the news published in Ohio newspapers, the testimony of inhabitants of the region where these flights were carried out and the photos of these flights, show that these flights occurred, but the aircraft did not take off by themselves, but instead they used artifacts that catapulted them, making Santos Dumont's flight considered the first in the history of aviation, despite having occurred a few years after the first flights of the Wright brothers.

In fact, the Wrights are credited in the United States as being the first to fly an airplane. His first public flights, carried out in the presence of a large number of witnesses, were carried out in 1908 in Le Mans (France).

Santos Dumont is considered the inventor of the airplane in most parts of the world, where he is called the father of aviation. Several people, however, criticize that title, claiming that other aviators made their contributions to the world of aviation long before Santos Dumont or the Wrights, and that that title should not be used for any particular aviator.

Other First Flight Controversies

Several aviators claimed to have flown in an airplane before the flights of the Wright brothers and Santos Dumont, making history's first flight in an airplane even more controversial. This controversy was fueled by the Wright brothers, who remained distanced from the media while preparing the patent for their aircraft, thus little known at the time by the global aviation community, and also by the large number of possible first flights in an airplane, due to the different categories and qualifications of the aircraft and the means used to achieve such flights, due to the lack of credible witnesses and due to the pride and patriotism of the nations of these aviators.

In Spain, Diego Marín Aguilera, on the night of May 15, 1793, made a 360-meter flight with an iron artifact and bird feathers, controlled by the pilot himself. Only a few testimonies and a belated recognition remain.

Gustave Whitehead claimed to have flown a heavier-than-air aircraft, under his own power, on August 14, 1901. He made the mistake of not documenting his alleged flight, but later, a replica of his aircraft named Number 21 successfully took flight. American Lyman Gilmore also claimed to have flown on May 15, 1902.

In New Zealand, farmer and inventor Richard Pearse built a monoplane that took flight on March 31, 1903. There is ample evidence that this actually happened, among accounts and photographs. But Pearse himself would later admit that this flight was not controlled and that he ended up crashing into a mountain after having flown at a height of about 3 meters. The German Karl Jatho flew in a heavier-than-air aircraft on the 18th. August 1903. His flight was short-lived, but the speed and design of the wings made the aircraft uncontrollable by the pilot. As late as 1903, witnesses claimed to have seen the Scotsman Preston Watson conducting flights at Errol, east of Scotland. But in the absence of photographic or documented evidence, they make it impossible to verify it.

The Romanian engineer Traian Vuia also claimed to have flown in an airplane, and that he managed to take off and stay in the air for a reasonable time, and without the help of any element. Vuia piloted the plane that he himself designed and built, on March 18, 1906 at Montesson, near Paris. None of their flights exceeded 100 feet. For comparison, by late 1905 the Wright brothers had already made 24-mile, 40-minute flights. However, the Wrights had to use a catapult to achieve this. the takeoff.

Many claims of flight are difficult to prove due to the fact that they reached so low that the planes blended in with the ground. In addition to that, the means used to take flight are also part of the debate. Some took flight completely by their own means, but there were others that were initially catapulted on takeoff, and in the air they were sustained by their own means. For all this, Alberto Santos Dumont and the Wright brothers are considered worldwide as the first to fly in an airplane, since there is plenty of evidence of their flights.

1906-1914

During these years, two inventors, the Frenchman Henri Farman and the Englishman John William Dunne, were also working on their own prototype airplanes on their own.

In January 1908, Farman won the Grand Prix of aviation, with an airplane that covered a kilometer, although flights had already covered more distance before, such as the one of the brothers Wright in 1905, covering a total of 39 kilometers. Later, on October 30, 1908, Farman became the first to make a city-to-city flight, made from the small town of Bouy and Reims, both in France (27 kilometers in 20 minutes). August 1909, he broke another record again, reaching 180 kilometers in just over three hours in his plane, the Farman III, and later 232 kilometers in four hours, 17 minutes and 53 seconds in that same device.

Dunne's initial work was sponsored by the UK Armed Forces, and tested at Glen Tilt (Scottish Highlands). The best design of his was the D4, which flew in December 1908 near Blair Atholl in Pertshire. His main contributions to the history of aviation were related to the stability of the machines, which was one of the main problems that the pioneers of aviation initially faced.

On May 14, 1908, Wilbur Wright made the first flight of an airplane loaded with two people, carrying Charles Furnas as a passenger.

On September 17, 1908, American Thomas Etholen Selfridge became the first person to die in an airplane in flight, when Wilbur Wright crashed his two-passenger plane in one of his military tests at Fort Myer (Virginia, United States). Also in 1908, Hart O. Berg became the first woman to fly, doing so as a passenger with Wilbur Wright at Le Mans, France.

On July 25, 1909, French engineer Louis Blériot became the first person to fly across the English Channel on board an airplane. Flying his plane Blériot XI, and starting from the French town of Calais, after 37 minutes in the air he managed to land near Dover, already in British territory. Thanks to his feat, Blériot won the prize of £1,000 offered by the English newspaper Daily Mail to the first person to do so.

Under the auspices of Peruvian President José Pardo, Carlos Tenaud was sent to study with Pedro Paulet. Tenaud would build his first airplane in 1909, similar to a butterfly that could only soar at a low altitude.The government sent him to France to train where he would be a student of Louis Blériot.

On March 8, 1910, Baroness de Laroche became the first woman to earn a pilot's license. She had made her maiden flight on October 22, 1909.

On September 23, 1910, the Peruvian-French aviator Jorge Chávez Dartnell together with his plane Blériot XI managed to cross the Alps for the first time from Brig (Switzerland) to Domodossola (Italy) where he 20 meters high the plane plummeted after the wings broke due to the strong wind. Seriously wounded, Chávez died four days later. Juan Bielovucic, also a Peruvian, would manage to overcome the Alps in 1913, without an accident, being the second man to cross the Alps.

In 1911, Calbraith Perry Rodgers became the first person to fly a transcontinental plane, traveling from Sheepshead Bay, New York, on the Atlantic Ocean, to Long Beach, California, on the Atlantic Pacific, in a series of short flights that would take a total of 84 days.

Advances in other types of aircraft

At the same time that fixed-wing aircraft were being developed, airships were becoming more and more advanced. During the first decades of the 20th century, airships were capable of carrying far more cargo and passengers than airplanes. Many of the advances related to airships were the work of the German Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin.

Construction of the first Zeppelin airship began in 1899 in Germany. The initial prototype, called LZ1 (German acronym for Luftschiff Zeppelin 1), was 128 meters long and was powered by two Daimler 14.2 CV engines each. The first flight of the LZ1 occurred on July 2, 1900, lasting just 18 minutes, because it was forced to descend because the control mechanism had suffered a mechanical failure. After repairing it, the Zeppelin was able to show its full potential in the following flights, surpassing the 6 m/s record of the La France airship by a margin of 3 m/s, but even so, it failed. attract potential investors. It took a few years for Ferdinand von Zeppelin to raise enough funds to continue his tests.

In 1902, the Spanish engineer Leonardo Torres Quevedo developed a new type of airship that solved the serious suspension problem of the gondola by including an internal frame of flexible cables that gave the airship rigidity due to the effect of internal pressure, combining the properties of rigid and flexible airships. Three years later, together with Alfredo Kindelán, Torres Quevedo built the first Spanish airship, called España, which was characterized by having a balloon separated into three compartments (trilobed), which increased safety. As a result of this fact, the collaboration between Torres Quevedo and the French company Astra began, which came to buy the patent with a transfer of rights extended to all countries, except Spain, to enable the construction of the airship in the country. Thus, in 1911, the manufacture of the airships known as Astra-Torres began. Some examples were acquired by the French and English armies from 1913, and used during the First World War in a wide variety of tasks, mainly naval protection and inspection.

In 1918, Torres Quevedo designed, in collaboration with the Spanish engineer Emilio Herrera Linares, a transatlantic airship, which they called Hispania, which reached the status of a patent, in order to carry out from Spain the first air crossing of the Atlantic Ocean. Due to financing problems, the project was delayed and it was the British John William Alcock and Arthur Whitten Brown who achieved this feat for the first time, in 1919.

In 1877 the Italian Enrico Forlanini developed an unmanned helicopter prototype, about 13 meters high and powered by a steam engine. It was the first of its kind. It achieved a vertical takeoff and remained in the air for about 20 seconds, although the first successful and recorded flight of a helicopter occurred in 1907, carried out by Paul Cornu in France, but not until 1936 with the Focke-Wulf Fw 61 of manufacture German, no functional helicopter was available.

The gyroplane was invented by the Spanish engineer Juan de la Cierva, who developed the articulated rotor that Igor Sikorsky would later use in his helicopters, even paying the patent and rights of use to the Spanish inventor. On its first flight in 1923, the autogyro managed to travel 200 meters, and later, it made the first trip between aerodromes from Getafe to Cuatro Vientos in 1924.

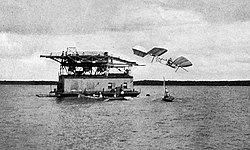

As for seaplanes, the first in history was the work of the French engineer Henri Fabre. He named it Le canard (French for 'the duck'), and on March 28, 1910 he took off from the water and managed to travel 800 meters. His experiments were closely followed by Charles and Gabriel Voisin, who acquired several of his prototypes to develop their own, which they named Canard voisin . In October 1910, the Canard voisin became the first seaplane to fly over the Seine River, in Paris, and in March 1912 it also became the first seaplane to be used militarily since the French aircraft carrier La Foundre (French for 'the lightning bolt').

1914-1918: World War I

Not long after it was invented, the airplane found its way into military service. The first country to use aircraft for this purpose was Italy. Bulgaria would follow suit in attacks on Ottoman positions during the First Balkan War.

But the first war in which aircraft were used in attack, defense and reconnaissance missions was in World War I. The Allies and the Central Powers made extensive use of aircraft. Ironically, the idea of using aircraft as a weapon of war before World War I was laughed at and jeered at by many military commanders in the days leading up to the war.

Aviation-related technology advanced rapidly because of the war. At the beginning of this, the planes could barely carry the pilot, but after many improvements, an additional passenger could be added. Engineers created more powerful engines, and aircraft were built with significantly better aerodynamics than before the war. As a comparison, at the beginning of the war the planes did not exceed 110 km/h, however at the end of the war, many already reached 230 km/h or even more.

After the war began, military commanders discovered the importance of the aircraft as a spy and reconnaissance weapon, being able to easily locate enemy forces and bases without much danger, until anti-aircraft weaponry began to be developed as it went along war.

But the use of reconnaissance patrol planes created a problem: they frequently encountered enemy planes. So it didn't take long to equip those aircraft with guns on board so they could defend themselves, but at the same time the pilot had to control the aircraft, which made things more complicated, so some planes had a spotter who could aim and fire a machine gun he carried in his arms, which was ineffective until the synchronized machine gun was developed.

The French would make a serious effort to solve this problem, and in late 1914, Roland Garros placed a fixed machine gun in front of his aircraft, allowing him to shoot while controlling the aircraft, thanks to covering the propellers with a metal plate that shielded them. On April 19, 1915, Garros was shot down and taken prisoner by the Germans, and because his plane was not destroyed, the engineer Anthony Fokker studied and improved the system, thanks to a mechanism that synchronized the rotation of the propeller with the shots of the machine gun, and that would end up being equipped in all the airplanes, reason why the air battles between fighters became very common. The use of seaplanes also spread, using them for reconnaissance missions in the sea, to be able to take pictures of enemy naval forces and to bombard enemy submarines.

At this time the name ace of aviation appeared, thus considering pilots who managed to shoot down five or more enemy aircraft in combat. Many of them would become famous people during and after the war. The most famous was the German Manfred von Richthofen, better known as the Red Baron, who managed to shoot down 80 enemy aircraft with different aircraft, although the most famous was the Fokker Dr.I that he used painted red. He was shot by a Canadian in 1918, shortly before the end of the war.

The most famous aircraft of the war was the Sopwith Camel, which claimed more aerial victories than any other Allied aircraft, but was also known for its difficult handling, responsible for the deaths of several novice pilots. Also from this period It is the Junkers J 1, a German-made aircraft that became the first all-metal aircraft in 1915.

1918-1939: The Golden Age of Aviation

In the period between the wars, all the technology related to aviation was developed, making important advances in the design of airplanes, and being the moment in which the first airlines began to operate. It was also a time when airmen began to impress the world with their feats and skills. Aircraft began to replace wood with metal in a widespread way. The engines also experienced a large increase in power. This series of technological advances, together with the increasing socioeconomic impact that airplanes came to have, led to the interwar period being considered the golden age of aviation. All this was possible in part, thanks to the large number of aircraft and pilots that remained after the First World War.

One of the main reasons for these developments was the delivery of a series of prizes that were awarded to aviators who managed to set records for distance flown and speeds achieved. An example of an award of these characteristics was the Orteig Award, which awarded 25,000 dollars to the first person to make the New York-Paris route or vice versa, without making stops of any kind. This award was won by Charles Lindbergh, who in his Ryan NYP single-engine monoplane (a modified Ryan M-2), christened Spirit of Saint Louis, took off from Roosevelt Airfield (Long Island, City of New York) on May 20, 1927 and after a flight of 33 hours and 32 minutes, he landed at Le Bourget airport, near Paris. But Lindbergh was not the first aviator to make a non-stop transatlantic flight. John William Alcock and Arthur Whitten Brown, two British aviators, managed to fly years earlier from Lesters Field, near Saint Johns, Nova Scotia (Canada), to Clifden (Ireland), from June 14 to 15, 1919 in their Vickers Vimy plane. IV (a modified bomber). For accomplishing this feat, Alcock and Brown won the £10,000 prize from the London newspaper Daily Mail, receiving the award from Winston Churchill. In addition, a year before Lindbergh's flight, the Spanish Plus Ultra seaplane, manned by Ramón Franco, Julio Ruiz de Alda, Juan Manuel Durán and Pablo Rada, crossed the South Atlantic from the town of Palos de la Frontera (Huelva, Spain) to Buenos Aires (Argentina), to emulate the voyage of Columbus, but by air, instead of by water.

In 1914, American Tony Jannus became the first pilot in history to fly commercially. Jannus piloted a seaplane to transport cargo and passengers between St. Petersburg and Tampa, Florida (United States). His seaplane had room for one passenger, who paid five dollars for a 22-mile flight. This air taxi, the St. Petersburg-Tampa Airboat Airlines considered the first airline in the world, in a short time ran into financial difficulties, so it lasted just a few months. In 1919 and through the 1920s, several airlines were established throughout Europe and the United States. These companies began using planes that had previously seen military use in World War I, but had been converted to carry cargo and passengers, and were elegantly decorated on the inside. Even so, these devices were very noisy and were not properly pressurized or conditioned.

After the war, the American and Canadian governments offered their excess planes to aviators at low prices. Despite the fact that these aircraft were stronger than those manufactured before the war, they still could not be considered safe, since they were made most of the time with wood and fabrics, and did not have basic navigation equipment. Even so, many pilots who had previously fought in the war bought these planes and used them to earn money, performing acrobatic and dangerous displays at fairs, which made accidents frequent, and many of these aviators died.

The United States Postal Agency also used old military planes to transport mail between some American cities, until 1927, when they stopped operating these flights, preferring to contract airlines to perform this service. Airmail was very important in the development of commercial aviation.

In 1929, technology related to airships advanced remarkably, with a Zeppelin making the first trip around the world, at the controls of Ferdinand von Zeppelin. In those years, airships were used by numerous airlines in Europe, and in the 1930s the first transatlantic routes began, which were very successful. The era of airships ended in 1937 when the Hindenburg airship crashed in Lakehurst, New Jersey, USA, killing 35 people. The event occurred because the airship was filled with hydrogen, a highly flammable gas. After this event, people stopped using airships, despite the fact that such an accident was the only one that occurred in this type of aircraft.

In the 1930s, many airlines used seaplanes that they used primarily for transoceanic flights. One of the largest seaplanes of the time was the Dornier Do X, so large that it needed twelve engines to take off, six on each wing. It first flew in 1929, but it was not very popular. Another seaplane, the Boeing 314 Clipper, capable of carrying 74 passengers, was popular in those years. In 1938 they made their first commercial flights over the Atlantic Ocean, but the development of increasingly powerful aircraft and airports with increasingly long runways meant that the use of seaplanes ended throughout the 40s.

Regarding other types of aircraft, in the 1920s the Spanish engineer Juan de la Cierva y Codorníu began to develop a rotary-wing aircraft that can be considered a hybrid between an airplane and a helicopter, and which received the name gyroplane. De la Cierva made his first flight in a gyroplane in 1923, covering 200 meters, and a year later in another test he managed to reach 100 km/h. The Spaniard continued to evolve his apparatus in England and the United States with the support of private investors, and became very successful with his models in the early 1930s. But with the arrival of the Spanish Civil War, de la Cierva died and the related investigations to the gyroplane are practically paralyzed, focusing all efforts on the development of the helicopter taking advantage of the research and advances made by Juan de la Cierva with the gyroplane, a device that today is considered the forerunner of the helicopter. Henrich Focke in Germany and Igor Sikorsky in the United States developed the first operational models of helicopters in the late 1930s and early 1940s, eventually having to purchase several of the gyroplane patents to develop their devices.

Years before, other pioneers made advances in helicopters, such as in Slovak Ján Bahýľ at the turn of the XX century, the Argentine Raúl Pateras Pescara, who made the first flight of a moderately controllable helicopter in 1916, or the Spanish Federico Cantero Villamil, who developed one of the first effective helicopters, the Libélula Viblandi, but the Spanish civil war paralyzed his projects.

Developments in aviation technology

During this period, and especially in the 1930s, there were various technical improvements that made it easier to build larger planes capable of traveling longer distances and flying faster and at higher altitudes, making it possible to carry more cargo and more passengers. Advances in the science of aerodynamics allowed engineers to develop aircraft whose design interfered as little as possible with the plane's flight. Control equipment and aircraft cabins would also improve considerably. In addition to that, improvements in radio communication technology allowed the use of this type of equipment on airplanes, so pilots could receive flight instructions from equipment on the ground, and pilots from different aircraft could also communicate with each other. All this generated more precise techniques of aerial navigation. Autopilot also came into use in the 1930s, allowing pilots to take short rest periods on long-duration flights.

The most characteristic aircraft of this stage was the Douglas DC-3, a twin-engine monoplane that made its first flights in 1936. It had a capacity for 21 passengers and was capable of reaching a cruising speed of 320 km/h. It quickly became the most widely used commercial aircraft of the time, and is considered one of the most important aircraft ever produced in aviation history.

The jet engine began to be developed in England and Germany in these years. Briton Frank Whittle patented a design for a jet turbine in 1930, and developed an engine that could be used for practical purposes by the end of the decade. German Hans von Ohain patented his version of a jet engine in 1936, and began developing a similar machine. None of them knew about the work that the other was doing, for this reason, both are considered their inventors. About to end World War II, Germany used the first jet aircraft and manufactured a series of Messerschmitt Me 262, the first jet fighter in history.

The fact that planes flew at higher and higher altitudes, where turbulence and other undesirable weather factors are rarer, created a problem: at higher altitudes, the air is less dense, and therefore has less of oxygen for respiration. As planes began to fly higher, pilots, crew, and passengers found it increasingly difficult to breathe. The specialists, to solve this problem, would create the pressurized cabin, which managed to keep the atmospheric pressure constant regardless of the flight height. These became popular in the late 1940s, although the first commercial airliner with a pressurized cabin was the Boeing 307, which made its maiden flight in 1938. Today, virtually all commercial passenger aircraft cabins are pressurized cabins..

Notable flights in this period

- 1919: The British John William Alcock and Arthur Whitten Brown made the first transatlantic crossing on a plane. They departed from Nova Scotia, Canada, to Clifden, Ireland. The flight travelled 3138 km, lasting approximately 12 hours.

- 1922: The Portuguese aviators, Sacadura Cabral (pilot) and Gago Coutinho (navegante) carried out the first aerial crossing of the South Atlantic.

- 1924: A U.S. Army Air Force Air Force Air Force Team successfully conducts the first air circumnavigation for 175 days, travelling more than 42 000 kilometres.

- 1926:

- The Spanish hydroplane Plus Ultra, led by Ramón Franco and Julio Ruiz de Alda, crossed the South Atlantic from the town of Palos de la Frontera (Huelva, Spain) to Buenos Aires (Argentina).

- The Elcano Squad, in charge of the Spanish captains Eduardo González-Gallarza, Joaquín Loriga Taboada and Rafael Martínez Esteve, together with their mechanics Pérez, Calvo and Joaquín Arozamena Postigo, performs a raid between Madrid (Spain) and Manila (Philippines) of 17 000 km, in 18 stages and throughout 39 days.

- American explorers Richard Evelyn Byrd and Floyd Bennett made the first flight over the North Pole.

- The Argentines Eduardo Alfredo Olivero, together with Bernardo Duggan and Emilio Campanelli, made a flight between Buenos Aires and New York, in 37 stages and throughout 81 days.

- 1927:

- Charles Lindbergh became the first person to cross the Atlantic Ocean on a solo plane flight. Its plane took off from New York (United States) and landed in Le Bourget (Paris, France), after travelling 5810 km in 33 hours and 32 minutes.

- The French Dieudonne Costes and Joseph Le Brix made the first unscheduled air cruise from the South Atlantic, flying from Saint Louis (Senegal) to Natal (Brazil), on a flight from Paris to Buenos Aires.

- 1928:

- Charles Kingsford Smith and Charles Ulm made the first flight over the Pacific Ocean, starting from Oakland (California, United States) to Brisbane (Australia), making stopovers in Honolulu and Suva.

- The Spanish aviator Juan de la Cierva overflew the Channel in an autogiro, a rotating wing aircraft invented by himself.

- 1929: Richard Byrd and his crew made the first flight over the South Pole.

- 1930: Amy Johnson became the first woman to travel alone between England and Australia.

- 1931: American pilots Clyde Pangborn and Hugh Herndon Jr. made the first flight across the Pacific Ocean with no stopovers, between Tokyo, Japan, and Wenatchee (Washington, United States).

- 1932: The American Amelia Earhart became the first woman to make a solo transatlantic flight, starting from Harbour Grace (Canada) and arriving at Londonderry (United Kingdom). The flight lasted 15 hours and 18 minutes.

- 1933:

- The Spaniards Mariano Barberán, Joaquín Collar Serra and Modesto Madariaga, carried out the crossing of the Atlantic Ocean between Seville (Spain) and Camagüey (Cuba), on board a Breguet XIX GR called Four Winds, being the greatest distance to that moment on the ocean.

- 1934:

- The Herberts Cukurs, with a plane designed and built by itself, left Riga (Latvia) towards Banjul (Gambia) and returns, on a journey of more than 19 000 km.

- 1935: Amelia Earhart became the first person to fly between North America and Hawaii on a single flight.

- 1936: Herbert Cukurs, with a plane designed and built by himself, left Riga (Latvia) to Tokyo (Japan), and returned, on a flight of 40 045 km.

- 1937: Amelia Earhart disappeared into the Pacific Ocean, in her attempt to become the first woman to turn the world into a plane, along with her partner Fred Noonan.

1939-1945: World War II

The years of World War II were characterized by a drastic growth in aircraft production, and by the great development of aviation-related technology. The following table shows the exponential growth in aircraft production in this period:

| Type of aircraft | Year 1940 | Year 1941 | Year 1942 | Year 1943 | Year 1944 | Year 1945 | Total units |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heavy pumps | 0 | 0 | 4 | 91 | 1147 | 2657 | 3.899 |

| Heavy pumps | 19 | 181 | 2241 | 8695 | 3681 | 27 874 | 42 691 |

| Media bombers | 24 | 326 | 2429 | 3989 | 3636 | 1432 | 11 836 |

| Light pumps | 16 | 373 | 1153 | 2247 | 2276 | 1720 | 7785 |

| Combat aircraft | 187 | 1727 | 5213 | 11 766 | 18 291 | 10 591 | 47 775 |

| Recognition aircraft | 10 | 165 | 195 | 320 | 241 | 285 | 1216 |

| Transport aircraft | 5 | 133 | 1264 | 5072 | 6430 | 3043 | 15 947 |

| Training aircraft | 948 | 5585 | 11 004 | 11 246 | 4861 | 825 | 34 469 |

| Liaison aircraft | 0 | 233 | 2945 | 2463 | 1608 | 2020 | 9269 |

| Annual total | 1209 | 8723 | 26 448 | 45 889 | 42 171 | 50 447 | 174 887 |

During the conflict, the first long-range bombers, the first practical jet aircraft, and the first jet fighter were developed. At the start of the war, the fighters could reach top speeds of 480 km/h and fly at an altitude of 9,000 meters. By the end of the war, after all the research and development by both sides, fighters were flying at 400 mph and many were reaching 40,000 feet.

Jet fighters developed during the conflict could move even faster, but they were not used until the end of the war. The first functional jet was the German Heinkel He 178, which made its maiden flight in 1939, shortly before the start of the war. Years later, in 1944, the Messerschmitt Me 262 became the first jet fighter to operate in the war, and could reach a top speed of 900 km/h. A German prototype, the Messerschmitt Me 163 was capable of 970 km/h in short flights, and served as the basis for the Messerschmitt Me 163 Komet, the fastest fighter of the war, which was used in some missions at the end of the war., in 1945. The Germans also created the first long-range ballistic missiles, the V-1 and V-2.

World War II bombers were capable of carrying twice the payload and traveling twice the distance of pre-war bombers. Long-range bombers made the most impact over the course of the war, as jet fighters began operating at the end of the war, and German defeat was a matter of time. The V-1 missiles were inefficient and the V-2s were not produced in large numbers. The American North American P-51 Mustang fighter was key along with the heavy bombers, since they served as protection against enemy fighters. Other famous aircraft of the war included the British Supermarine Spitfire fighter, widely regarded as 'the savior of the UK', the Japanese Mitsubishi A6M Zero fighter and the American Boeing B-29 Superfortress bomber.

1945-1980

Turboprops

After the end of World War II, commercial aviation began to develop independently of military aviation. Aircraft manufacturing companies began to create models specially designed for passenger transport and, during the first years after the war, airlines used military aircraft modified for civilian use, or versions derived from them, among which it would be worth mentioning the Boeing 377 Stratocruiser, which was derived from the Boeing C-97 Stratofreighter, and which became the first double-decker aircraft in aviation history, since its fuselage called "double-bubble" It allowed a deck with seats to be housed at the top, and a small VIP room at the bottom that was accessed by a spiral staircase, and which at the same time was the largest commercial aircraft until the arrival of the Boeing 707 in 1958..

Of the commercial aircraft that were developed in this period, the four-engine Douglas DC-4 and the Lockheed Constellation stand out, which were used for local passenger or medium-distance flights. They also made transoceanic routes, but for these they needed to make stops to refuel. Transoceanic flights needed more powerful engines, which already existed in 1945 in the form of jet turbines, but these, at that time, still consumed too much fuel and with them an airplane could only travel short distances.

To solve this problem, even temporarily, turboprop engines were developed, which were propellers capable of generating more than three thousand horsepower. These engines would begin to be used in the Vickers Viscount, Lockheed L-188 Electra or Ilyushin Il-18, aircraft capable of transporting between 75 and 110 passengers between the cities of New York and Paris without stops and at a cruising speed of more than 500 km/h.

Age of Jets

In the late 1940s, instructors began the turbines used in jet fighters produced during World War II. Initially, the United States and the Soviet Union wanted jet engines to produce ever-better bombers and fighters to further improve their military arsenal. When the Korean War began in 1950, both the United States and the Soviet Union had jet fighters, most notably the American North American F-86 Saber and the Soviet MiG-15.

As for the first commercial jet aircraft in aviation history, it was the British-made de Havilland Comet. The Comet began its use as a passenger aircraft in 1952, being capable of flying at 850 km/h h, and with a relatively quiet, pressurized cab. This aircraft began as a commercial success, with many airlines placing orders. But two accidents that occurred in 1954 in the middle of the sea raised great doubts regarding the safety of the plane. The main cause of the accidents was due to the fatigue of the metal around the window where the radio unit was housed, and of the windows that were both square, which ended up succumbing at the edges to the cabin's pressurization. Hence, since then the windows of the airplanes are oval, to dissipate the energy around them. The de Havilland company tried to save its plane, whose sales had fallen drastically, through some structural modifications, but a third accident in 1956 caused sales to fall again, and production finally ceased in 1964.

The North American company Boeing launched the Boeing 707 in 1958, which became the first successful jet airliner. The engineers who developed the model made a special effort to ensure that the mistakes that had been made in the de Havilland Comet did not occur in the 707. The Douglas DC-8 and Convair 880 jet models were launched a few years later, although the success The commercial that both models had was more modest than that reached by the 707, of which a total of 1010 units were produced, making Boeing since then the largest aircraft manufacturer in the world.

The 727, 737 and 747 models are direct derivatives of the 707. The Boeing 737, whose production began in 1964, is the most produced and popular passenger airliner in history, with more than six thousand aircraft produced, and well into the 21st century, the model continues in production, thanks to all the improvements and variants produced.

Wide-body aircraft

Wide-body aircraft are commercial aircraft that have three rows of seats separated by two aisles. They were created to provide more comfort to passengers, and to facilitate their mobility and that of the crew members around the plane.

The first wide-body aircraft was the Boeing 747, nicknamed Jumbo, capable of carrying more than 500 passengers in a single flight. It was introduced in 1968, and at that time many they thought it would not be commercially successful, so Boeing ran into financial problems during the development process of the aircraft. However, the Jumbo became a commercial achievement, breaking all expectations, and going on to serve routes with a high density of passengers. From its launch it was the largest commercial aircraft in the world until the appearance of the Airbus A380, already in the XXI century.

In the 1970s, the first commercial trijets appeared, the McDonnell Douglas DC-10 and the Lockheed L-1011 TriStar, capable of intercontinental routes, also the birth of the F-14 Tomcat on December 21 of that year and they were very successful at the time. Years later, a derivative of the DC-10 would also be produced, the McDonnell Douglas MD-11.

The first wide-body twin jet was the Airbus A300, a medium-range commercial airliner, manufactured by the European consortium Airbus. The North American Boeing counterattacked with the Boeing 767, similar to the A300 but could operate longer routes, and with the Boeing 757 for medium-range routes, but which did not have a wide body. The Boeing 767 revolutionized commercial aviation, since its long range, its low operating costs and its transport capacity (it could carry more than 200 passengers) allowed regular flights using the fewest number of aircraft possible on transatlantic routes and previously impractical routes. due to high operational costs and low number of passengers. Thanks to this aircraft, transatlantic travel became popular, and in the late 1980s and early 1990s, there were more Boeing 767s crossing the Atlantic Ocean daily than all other commercial aircraft operating those routes combined, and during the early years of the [[XXI]] century, continues to be the aircraft that is used the most times to cross the Atlantic daily, despite of the growing competition from newer and more modern aircraft.

Supersonic flight

After the end of World War II, the technology needed to perform controlled supersonic flight was not yet available. On top of that, the planes were not yet strong enough to withstand the strong shock waves generated by supersonic speeds. At sea level, the speed of sound is about 1,225 km/h, but at 15,000 meters, it's only 1,050 km/h. In fact, some aviators in World War II managed to pass the sound barrier, but with catastrophic results: the strong shock waves generated by speed destroyed planes that had not been designed to reach those speeds.

In 1947, American engineers began working on small prototypes of uncontrolled aircraft. The biggest concern of aviation specialists was that these planes would resist the shock waves that are created at high speeds. The good results obtained in these tests would lead to the production of a series of planes that they called X-planes (X-planes in English). American Charles Yeager became the first person to exceed the speed of sound, on October 4, 1947, piloting a Bell X-1 named Glamorous Glennis.

In 1962, the North American X-15 rocket plane became the first aircraft to reach the thermosphere, piloted by American Robert White. He managed to stay at an altitude of 95,936 meters for sixteen seconds, covering approximately 80 kilometers in that period. This was the first flight of an airplane through space. Later, the X-15 would reach 107,960 meters of altitude, and also became the first hypersonic aircraft (5 times the speed of sound), breaking various speed records, and exceeding Mach 6 (six times the speed of sound).) on various flights.

The first supersonic aircraft for civilian use were created in the late 1960s. The world's first commercial supersonic aircraft was the Soviet Tupolev Tu-144, which made its maiden flight on December 31, 1968.

The Concorde, made by a Franco-British consortium, made its maiden flight two months later. The Tu-144 began its first passenger flights in 1977, but due to operational problems, it ceased to be used as a passenger plane the following year. As for the Concorde, it made its first commercial flights in 1976, serving transatlantic routes. Both aircraft have been, to date, the only commercial supersonic aircraft to have been developed. In 2004, its commercial flights were suspended, leaving the Concordes as specimens in aviation museums around the world.

From Earth to space

With the space race at the center of the Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union, the sky was literally no longer the limit, at least for controlled flight. In 1957 the Soviet satellite Sputnik became the first satellite to orbit the earth, and in 1961, Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin became the first person to travel into space, orbiting the planet once, and staying there. for 108 minutes. The United States reacted months later by launching astronaut Alan Shepard into space, and years later, launching the first mission to the Moon within the Apollo Program. On July 20, 1969 Neil Armstrong, commander of the Apollo 11 mission, would become the first person to set foot on the moon.

1980-2000

On June 12, 1994, the Boeing 777 made its maiden flight, becoming the first aircraft designed and planned entirely with computers, and is currently the largest twin-jet aircraft in the world. Together with the Airbus A340 quad-jet, they are the aircraft with the longest operational range on the planet, being able to cover more than 16,000 kilometers in a single flight.

Since the 1970s, airports and commercial aircraft have become one of the preferred targets for terrorist attacks (air piracy). The worst of these attacks occurred in 2001, when two American Airlines planes and two United Airlines planes were used in the 9/11 attacks. As a direct consequence of this event, the number of air travelers decreased in most airlines, and many of them faced great financial difficulties in the following years. The effects of the attack, although minimized, still persist in several companies. The result of the terrorist threat is the increase in security measures that have been taken at airports since then.

21st century

Since the beginning of the XXI century, subsonic aviation has sought to replace the pilot with remote-controlled or computer-controlled aircraft. In April 2001, the Northrop Grumman RQ-4 Global Hawk drone flew from Edwards Air Force Base, California, United States, to Australia, non-stop and without refueling, taking 23 hours and 23 minutes. being the longest flight made by an unmanned aircraft.

One of Air France's Concordes crashed on July 25, 2000, when a turbine on the plane caught fire, causing it to crash in Gonesse, France shortly after takeoff. Until then, the Concorde was considered the safest commercial aircraft in the world. It went through a modernization process until 2003, but due to low passenger numbers and high operating costs, all aircraft stopped flying in 2003, when British Airways withdrew the last one in service, and since then no supersonic aircraft. perform commercial flights.

On April 27, 2005, the Airbus A380 flew for the first time, and on October 25, 2007, with the completion of its first commercial flight between Singapore and Sydney, it became the largest commercial passenger aircraft in the world. world, surpassing the Boeing 747, which had held that record since it made its maiden flight in 1969. But even so, the A380 is surpassed in size by the Antonov An-225, which made its maiden flight on December 21, 1988, and since then it has been the largest aircraft in history.

On December 15, 2009, after two years of delay, the Boeing 787 made its first flight at the company's facilities at the Paine Field airport (Everett, Washington, United States), becoming the first commercial airplane made mainly of composite materials.

The impact on aviation of the COVID-19 pandemic has been significant due to the resulting travel restrictions, as well as the drop in demand among travelers, and may also affect the future of air travel. For example, the mandatory use of face masks on airplanes has become a common feature of flights so far in the 2020s.

The future

Since the beginning of the 1990s, commercial aviation began to develop technologies that in the future will make the airplane an increasingly automated device, gradually reducing the importance of the pilot in the operations of the aircraft, with the intention to reduce air accidents caused by human error. Commercial aircraft manufacturers continue to investigate possible ways to improve them, making them increasingly safer, more efficient and quieter. At the same time, pilots, air traffic controllers and mechanics will be increasingly better prepared and aircraft will undergo more rigorous inspections in order to avoid accidents due to human or mechanical failure.

The reusable launch system, also known by its acronym RLV (Reusable Launch Vehicle) is a launch vehicle that is capable of being launched into space more at once, thanks to its reusable rockets, which would generate enough thrust to reach space and once there, orbit around the planet. These aircraft will be able to take off and land in the same way as airplanes, on long runways. Although they are not yet available, there are several models that are in the testing phase, such as SpaceShipOne, which became the first privately-owned manned space vehicle. Over time, they could be used for low-cost space travel. and high security. However, in order for them to be used multiple times, they need to have a stronger structure to withstand continued use, which would increase the weight of the device, and given the lack of experience with these vehicles, costs still have to be considered. what it would entail.