Averroes

Averroes (Latinization of the Arabic name أبو الوليد محمد بن أحمد بن محمد بن رشد ʾAbū al-WalīdʾMuhammad ibn Aḥmad ibn Muḥammad ibn Rušd; Córdoba, Al-Andalus, Almoravid Empire, April 14, 1126 – Marrakech, Almohad Empire, December 17, 1198) was an Andalusian philosopher and physician. Muslim, teacher of philosophy and Islamic law, mathematics, astronomy and medicine.

Averroes comes from a family of legal scholars. His grandfather was Córdoba's main qadi under the Almoravid regime and his father held the same position until the arrival of the Almohad dynasty in 1146. Averroes himself was appointed qadi of Seville and served in the courts of Seville, Córdoba and Morocco during his career.

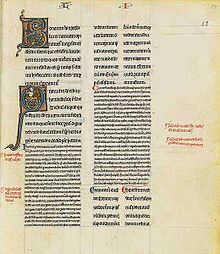

In addition to producing a medical encyclopedia, he wrote commentaries on the work of Aristotle; hence he was known as "the Commentator." In his work Refutation of the refutation (Tahafut al-tahafut) he defends Aristotelian philosophy against Al-Ghazali's assertions that philosophy would be in contradiction with religion and It would therefore be an affront to the teachings of Islam. Jacob Anatoli translated his works from Arabic into Hebrew during the XIII century.

At the end of the XII century a wave of Islamic fundamentalist fanaticism invaded Al-Andalus after the conquest of the Almohads, and Averroes was exiled and isolated in Lucena y Cabra, near Córdoba, and his works were prohibited. Months before his death, however, he was vindicated and summoned to court in Morocco. Many of his works on logic and metaphysics have been permanently lost as a result of censorship. Much of his work has only been able to survive through translations in Hebrew and Latin, and not in its original Arabic. His main disciple was Ibn Tumlus, who had succeeded him as chamber physician to the fifth Almohad Caliph Al-Nasir.

In the West, Averroes was known for his extensive commentaries on Aristotle. His thoughts generated controversy in Latin Christianity and sparked a philosophical movement called Averroism based on his writings. Averroes's theory on the unity of the intellect became one of the best known and most controversial Averroist doctrines. His works were condemned by the Catholic Church in 1270 and 1277. Although weakened by rebuttals by St. Thomas Aquinas, Latin Averroism continued to attract followers into the XVI .

Biography

Childhood and education

Muhammad ibn Ahmad ibn Muhammad ibn Rushd grew up in a family known for its public service, especially in law and religion. His grandfather Abu al-Walid Muhammad was the chief qadi of Córdoba and imam of the aljama mosque under the government of the almoravids. His father, Abu al-Qasim Ahmad, was not as well known as his grandfather, but was also a Qadi until Almohad control of the city in 1146.

According to his traditional biographers, Averroes' education was "excellent," beginning his studies in hadith (traditions of the Prophet Muhammad), jurisprudence, medicine, and theology. He learned Maliqui jurisprudence from al-Hafiz Abu Muhammad ibn Rizq and hadith from Ibn Bashkuwal, a pupil of his grandfather. His father also provided him with knowledge of jurisprudence. The field of medicine was taught to him thanks to Abu Jafar Jarim al-Tajail, who surely also taught him philosophy. Similarly, he knew the writings of the philosopher Ibn Bajjah, better known as Avempace, and perhaps even knew and tutored him personally. He attended regular meetings of philosophers, doctors and poets in Seville, attended by philosophers such as Ibn Tufayl, Ibn Zuhr or the future caliph Abu Yusuf Yaqub. Likewise, he studied the kalam theology of the Ashariyyah school, which he himself will later criticize. His 13th century biographer, Ibn al-Abbar, wrote that he was more interested in the study of laws and their principles than in the hadith, especially the khilaf, disputes and controversies of Islamic jurisprudence. Ibn al-Abbar also mentions his dedication to the "sciences of the ancients", referring to the philosophy and science of ancient Greece.

Career

In 1153 Averroes was in Marrakech, the capital of the Almohad Caliphate, to make astronomical observations and to support the Almohad project to build new educational institutions. He hoped to find some kind of physical laws about astronomical movements instead of the mathematical laws that were the only ones known at the time, although his research did not bear fruit. During his stay in Marrakech, he met Ibn Tufayl, a renowned philosopher, author of Hayy ibn Yaqdhan , who was also a physician at the Caliphate court. Averroes and Ibn Tufayl began a friendship despite their philosophical differences.

In 1169, Ibn Tufayl presented Averroes to the Almohad caliph Abu Yaqub Yusuf. According to the chronicles of the historian Abdelwahid al-Marrakushi, the caliph asked Averroes if the sky had always existed or had been created. Worried about the answer he might give, since he might create a controversy and endanger him, he decided not to answer. The caliph then developed the ideas of Plato, Aristotle and other Muslim philosophers related to the subject and discussed them with Ibn Tufayl. This display of knowledge reassured Averroes, explaining his ideas on the matter, which impressed the caliph. Averroes was also impressed by it, reporting that the caliph had a "great desire to learn, something he did not imagine".

After this first meeting, Averroes remained under the caliph's protection until his death in 1184. When the caliph complained to Ibn Tufayl about the complexity of understanding Aristotle's works, Ibn Tufayl recommended that he urge Averroes to write about it.; this was the beginning of the philosopher's voluminous commentaries on Aristotle, whose first commentaries were written in 1169, leading to his being known as the Commentator.

That same year, Averroes was appointed qadi of Seville and in 1171 he was appointed qadi of his hometown, Córdoba. As a qadi he would adjudicate cases and issue fatwas (legal opinions) based on Islamic law, the sharia. The production of his writings grew exponentially during this time, despite his many obligations and his travels within the Almohad Empire, tours that he took advantage of to investigate astronomy again. In 1179 he was again named qadi of Seville. In 1182 he succeeded his friend Ibn Tufayl as court physician and that same year he would be appointed chief cadí of Córdoba, a prestigious position previously held by his grandfather.

In 1182 Caliph Abu Yaqub died and was succeeded by Abu Yusuf Yaqub al-Mansur. At first Averroes was in royal favour, although finally in 1195 his fortunes turned. He was charged with several crimes and he was accused by a court in Córdoba. Said court condemned his works and ordered their burning and exiled Averroes from the city to nearby Lucena and Cabra. Some biographers attribute this change to a possible insult to the caliph in his writings, although more recent research links it to political motives. The Encyclopedia of Islam explains that the caliph distanced himself from Averroes and moved closer to the more orthodox positions of the ulema, who opposed Averroes and whose support was necessary for the caliph in order to combat the Muslims. Christian kingdoms.

After a few years, Averroes returned to the court of Marrakech and enjoyed Caliphate favor again. He died soon after, on December 11, 1198.

Philosophy of knowledge

Averroes' noetics, formulated in his work known as Great Commentary, starts from the Aristotelian distinction between two intellects, the nous pathetikós (receptive intellect) and the nous poietikós (agent intellect), which made it possible to separate philosophical reflection from mythical and political speculation.

Averroes strove to clarify how human beings think and how it is possible for perishable beings to formulate universal and eternal truths.

The Cordovan philosopher distanced himself from Aristotle by emphasizing the sensory function of the nerves and by recognizing in the brain the location of some intellective faculties (imagination, memory...).

Averroes locates the origin of intellection in the sensible perception of individual objects and specifies its end in universalization, which does not exist outside of the soul (the principle of animals): the process consists of feeling, imagining and, finally,, grasp the universal.

That universal has, moreover, existence insofar as it is by what is particular. In any case, it is the intellect or understanding that provides universality to what starts from sensible things.

Thus, in his work Tahâfut he exposes the need for science to adapt to concrete and particular reality, since there can be no direct knowledge of universals.

Averroes' conception of intellect is changeable, but in its broadest formulation he distinguishes four types of intellect, that is, the four phases that understanding goes through in the genesis of knowledge: material (receptive), habitual (which allows us to conceive everything), agent (efficient and formal cause of our knowledge, intrinsic to man and that exists in the soul) and acquired (union of man with the intellect).

Averroes also distinguishes between two subjects of knowledge (more properly: the subjects of intelligibles in act): the subject through which these intelligibles are true (the forms that are true images) and the subject through which they are true. intelligible are an entity in the world (material intellect). Consequently, the subject of sensation (for which it is true) exists outside the soul and the subject of the intellect (for which it is true), within.

Transcendence

Despite the condemnation of 219 Averroist theses by the Parisian bishop Étienne Tempier in 1277 because of their incompatibility with Catholic doctrine, many of these survived in later literature by authors such as Giordano Bruno or Giovanni Pico della looking at her Thus, we find in these authors a defense of the superiority of the contemplative-theoretical life over practical life (in line with what was defended by Aristotle in his Nicomachean Ethics, X or in y a vindication of the character instrumental-political of religion as a doctrine destined for the government of the masses incapable of giving a law to themselves through reason.Religious law, Averroes had said in his Tahafut al-tahafut (تهافت التهافت), provides the same truth that the philosopher reaches by inquiring into the cause and nature of things; however, this does not imply that philosophy acts in any way in educated men as a substitute for religion: «philosophers believe that religions are necessary constructions for civilization (...)» The existence of religion is also necessary for the integration of the philosopher into civil society.

Other theses that we find in Averroes are:

- That the world is eternal.

- That the soul is divided into two parts, a perishable individual (passive intellect) and another divine and eternal (active intellect).

- The active intellect is common to all men.

- The active intellect becomes passive intellect when it is attached to the human soul. When man's imaginative faculty receives the images that give him the activity of the senses, it transmits them to the passive intellect. The forms, which exist in power in such images, are updated by the active intellect, becoming concepts and judgments. That is why he was fought by Christian theologians.

In order to overcome the incompatibility of Averro's theses with Christian doctrine, Siger de Brabant proposed the doctrine of double truth, according to which there is a religious truth and a philosophical and scientific truth. This doctrine would be adopted by the majority of European defenders of Averroism.

Main works

- Tahafut al-tahafut (تهافت التهافت, Refutation refutation or Destruction of destruction, Destructio destructionis in Latin)

- Kitab fasl al-maqal (On the Harmony between Religion and Philosophy)

- Bidayat al-Mujtahid (Distinguished jurist)

- Comments to the “Corpus aristotelicum”, which include:

- The minor comments (Yawami) to the Isagoge de Porfirio, to the Organon, Rhetoric, Poetics, Physics, De Coelo et Mundo, De generatione et corruptione, Meteorological, De Anima, Metaphysics, De partibus animalium, De generatione animalium and Parva Naturalia, of Aristotle.

- Media comments (Taljisat) to the Isagoge de Porfirio. the Organon, Rhetoric, Poetics, Physics, De Coelo et Mundo, De generatione et corruptione, Meteorological, De Anima, Metaphysics and Ethics nicomaquea, by Aristotle.

- Senior Comments (Tafasir) to the Second Analyticals, Physics, De Coelo et Mundo, of Anima and Metaphysics of Aristotle.

- Exhibition of the Republic Plato

- Comments to Ptolomeo, Alejandro de Afrodisias, Nicolás de Damascus, Galeno, al-Farabi, Avicena y Avempace

- The treaty From Substantia Orbis

- Three important theological writings: Fasl al-Maqal, Kasf'al-Manahiy and Damima

Medicine

Averroes, who served as physician to the Almohad court, wrote several treatises on medicine. The most famous is Kitab al-kulliyyat al-Tibb ( Book of generalities of medicine ), Latinized in the West as the Colliget , written about 1162, before his appointment at court. The title of this book is contrary to al-Juz'iyyat fi al-Tibb (The particularities of medicine), written by his friend Ibn Zuhr, since both collaborated on purpose so that their works complemented each other. The Latin translation of the Colliget became a reference book on medicine in Europe for centuries. Other titles that have survived are On Sentimentality, Differences in Temperament and Medicinal Herbs. In addition, he wrote summaries of the works of the Greek physician Galen (f. 210) and a commentary on Avicenna's Poem of Medicine.

Summary of the Kitab fasl al-maqal

Decisive treatise that determines the nature of the relationship between religion and philosophy

- The law obliges to study philosophy

- If the theological studies of the world are philosophical, and the law compels such studies, then the law compels them to make philosophy.

- The law compels these studies.

- These studies must be done in the best way, through demonstrative reasoning.

- To master this instrument, the religious thinker must conduct a preliminary study of logic, just as a lawyer has to study legal reasoning. This is no more heretic in one case than in the other. And logic has to be learned from antiquity teachers, regardless of the fact that they are not Muslims.

- After logic we must proceed to philosophize correctly. We must also learn from our predecessors, just as in mathematics and laws. It is therefore wrong to prohibit the study of ancient philosophy. The danger you may pose is accidental, such as the danger of taking medicine, taking water or studying laws.

- For every man the law has foreseen a path to the truth according to its nature, through demonstrative, dialectical or rhetorical methods.

- Philosophy contains nothing that opposes Islam

- Demonstrative truth and the truth of scriptures cannot be in conflict.

- If the apparent meaning of Scripture is in conflict with the conclusions of the demonstration, then they must be interpreted allegorically, that is, metaphorically.

- With regard to such difficult questions, the error made by a qualified judge in the matter is forgiven by God, while the error by an ununderstood person in the matter is not forgiven.

- Philosophical interpretations of Scripture should not be taught to the majority. The law provides other methods to teach them.

- The purpose of Scripture is to teach the theoretical and practical sciences and practice and correct attitudes.

- When symbols are used, each type of person, demonstratives, dialectics or rhetoric should try to understand the symbolized inner sense or to subtract it to the content with the apparent sense, according to their abilities.

- Explaining the inner sense to people who are not able to understand, is destroying their faith in the apparent sense without replacing it with something else. The result is descreening in students and teachers. It is better for scholars to profess ignorance, citing the Quran on the limits of human understanding.

- The appropriate methods to teach people are indicated in the Quran, as the first Muslims knew. The popular parts of the Book are wonderful in responding to the needs of all kinds of minds.

Averroes in literature

Averroes is the protagonist of the story The Search for Averroes in El Aleph, by Jorge Luis Borges. Averroes, like Ibn Rushd, is one of the characters in the novel Two Years, Eight Months and Twenty-eight Nights by Salman Rushdie. He is also mentioned in the fourth canto of Dante's The Divine Comedy. Finally, Averroes is part of a novel by the author Ikram Antaki in his book The Spirit of Córdoba, which together with another Cordovan philosopher, discuss topics on mathematics, religion and humanism.

Eponymy

- The lunar crater Ibn-Rushd bears this name in his memory.

Contenido relacionado

Olmec culture

V millennium BC c.

Murphy's War