Auto de fe

The auto de fe was a public act organized by the Inquisition in which those convicted by the court abjured their sins and showed their repentance —which made possible their reconciliation with the Catholic Church—, so that it would serve as a lesson to all the faithful who had gathered in the public square or in the church where it was celebrated (and who were also invited to solemnly proclaim their adherence to the Catholic faith).

The aforementioned was the intended meaning of the auto de fe, in which those sentenced to death by the ecclesiastical court —the relapses (repeat offenders)— were released to the secular arm, that is, delivered to the secular authority, which was in charge of carrying out the death sentence, leading the prisoners to the place where they were going to be burned —previously strangled if they were penitents, and burned alive if they were unrepentant, that is, if they had not recognized their heresy or did not repent.

The auto-da-fé that was carried out discreetly in the offices of the Inquisition was called an autillo.

Purpose

The purpose of the Inquisition processes was not to save the souls of the condemned but to guarantee the public good by "extirpating" heresy. Hence, the reading of the sentences and abjurations had to be done publicly "for the edification of all and also to inspire fear", as the jurist Francisco Peña pointed out in 1578 in his commentary on Nicholas Eymerich's Inquisitor's Handbook. Thus, it was essential that the condemned man affirm before the assembled public that he had sinned and that he repented, so that it would serve as a lesson to all those who listened to him, and to those who were also invited to solemnly proclaim his faith. That was the purpose of the auto-da-fe.

However, according to Henry Kamen, "what began as a religious act of penance and justice ended up being a public festival more or less similar to bullfights or fireworks". "People flocked to see them because they were a strange sight, alien to their usual faith, religious practices, everyday existence". The popularity of the autos de fe also contributed to the prestige they achieved from the autos de fe of 1559 because the king attended —until then the kings of the Hispanic Monarchy had not participated, except in one held in Valencia in which he was present. present Carlos I—, and the changes introduced by the Inquisition from that date to increase its solemnity and magnificence in order to dazzle the faithful.

According to Kamen himself, among the foreigners who visited Spain, the autos-da-fe caused "astonishment and disgust at a practice that was unknown in the rest of Europe. The Flemish Jean Lhermite, who attended an auto-da-fe in the company of Philip II in Toledo in February 1591, later went to watch the executions, describing the whole affair as a "very sad spectacle, unpleasant to see." 3. 4;. No doubt it must have been terrifying to see clerics presiding over a ceremony in which the condemned were executed, but in reality public executions in other countries were not much different from an auto-da-fe, and sometimes exceeded it in savagery&# 34;.

History

The first autos-da-fe were the work of the medieval pontifical inquisition, under the name Sermo Publicus or Sermo Generalis Fide -so called because it began with a sermon—, but they were held only in the Toulouse region on the occasion of the repression of the Cathar heresy.

The first auto-da-fe of the Spanish Inquisition took place in Seville on February 6, 1481, and in the early days they were sober and austere acts. "The public hardly attended the autos; instead of an elaborate ceremonial, there was little more than a simple religious rite determining the penalties for arrested heretics. The ceremony was not even necessarily held on a public holiday, proof that the public was not in attendance". We have an account of the first auto-da-fe held in Toledo on Sunday, February 12, 1486, in which it is said that 750 reconciled Jewish converts left in procession from the church of San Pedro Mártir. "With the great cold that it was, and the disgrace and diminishment that they received because of the great people who watched them, because many people came from the regions to watch them, and they are giving very loud screams, and some crying mesavan; They believed themselves more because of the dishonor they received than because of the offense they did to God". When the procession reached the "greater church" at the door there were two chaplains, who made the sign of the cross on each one's forehead, saying these words: «Receive the sign of the cross, which you denied and misled you lost»". Inside the church, "where they said mass and preached to them", they were called one by one, and they were then read "all the things in which they had judiciously ". "And after this was finished, there they were publicly penanced".

In 1504, one of the most important autos-da-fé of the Inquisition was held in Córdoba. After hundreds of cases passed through the court, 107 people, men and women, were burned alive, possibly in the largest auto-da-fe ever.

Throughout the XVI century, the autos-da-fe grew in solemnity and duration. painting by Pedro Berruguete Auto de Fe presided over by Santo Domingo de Guzmán (c. 1500), which was commissioned by the Inquisitor General Torquemada for the altarpiece of the Convent of Santo Tomás de Ávila. Henry Kamen points out that the painting is "totally made up" and that it is possible that it served as a model for the new auto-da-fe ceremonial established in the Instructions of 1561.

Two of the most famous acts of faith due to their solemnity were celebrated in the Plaza Mayor of Valladolid on May 21 and October 8, 1559. In the first of the two, fourteen people were burned, including Agustín and Francisco of Cazalla and Constanza de Vivero, and the bones and statue of another, and sixteen were reconciled with penance. In the second, thirteen people were burned, such as Isabel, wife of Carlos de Seso, Marina de Guevara, and the bones of another, and there were also sixteen other penitentiaries. Surely these two historical acts inspired Miguel Delibes the one described in his novel El hereje . Another literary reference is found in the novel Auto de fe by the Bulgarian-Austrian-English author, Elías Canetti, written in 1935, banned by the Nazis and unknown until the 1960s XX.

The autos-da-fe of 1559 held in Valladolid and Seville to eliminate the Protestant foci that had arisen in those two cities served as a model for the later ones, and this was stipulated in the Instructions issued in 1561 by the Inquisitor General Fernando de Valdés.

The attendance of the authorities and officials at the auto-da-fe will become mandatory from 1598 under penalty of excommunication. The Inquisition grants the presidency of the act to a member of the high nobility and when it is held in Court it will try to get the king to attend. This was what happened with the two autos-da-fe held in Valladolid in 1559 in which the city's Protestants were condemned. The first was attended by the Regent Juana of Austria and the second by King Philip II, who had just returned from the Netherlands. The following year the court of Toledo organized an auto-da-fe on the occasion of the marriage of Felipe II with Isabel de Valois, and in 1564 another was organized in Barcelona on the occasion of the king's visit to celebrate the Cortes of Catalonia. Felipe II presided over other autos-da-fe —in Lisbon in 1582 and in Toledo in 1591— since, according to Joseph Pérez, "apparently, he liked these ceremonies very much, and not out of sadism, as has been said many times —let's remember that those sentenced to death are executed after the auto de fe, and that the authorities do not attend the execution—, but by pomp: procession, mass, sermon...".

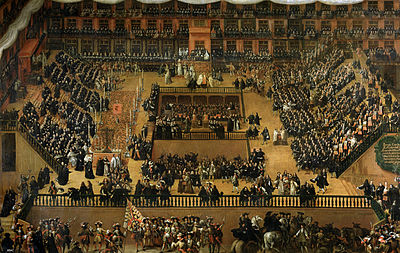

Philip III also presided over some auto-da-fe, such as the one held on March 6, 1600 in Toledo, and Philip IV asked that one be held at court in 1632 to celebrate the healing of his wife, Isabel de Borbón. Under the pretext of the wedding of King Carlos II and María Luisa de Orleans, one of the most famous auto-da-fes was held in Madrid in 1680 due to the painting by Francisco Rizi and the "Relation" of the same written by José del Olmo, who as a relative of the Holy Office had been one of the organizers of the ceremony and the designers of the dais where the authorities sat. The king chose the date, June 30, the feast of Saint Paul, "to mark the great triumph of the Catholic faith and the defeat of Jewish obstinacy". In the 18th century the auto-da-fés are increasingly rare and discreet, and the last one the king attended was held in 1720, under Felipe V.

One of the reasons for the progressive decrease in the number of autos de fe was that they were expensive and the Inquisition, which was not as rich as people believed, did not always have the necessary funds. The decline can already be seen in the 17th century. Thus, while in Seville in the second half of the XVI century, at least twenty-three autos-da-fe were held, in Madrid between 1632 and 1680 none were held.

The last auto-da-fe

In Portugal, on October 1, 1774, Sebastião José de Carvalho e Melo published a decree requiring verdicts of the Holy Office to require royal sanction, effectively ending the Portuguese Inquisition. Autos-da-fe were no longer organized in Portugal.

According to Emilio La Parra and María Ángeles Casado, the last general auto-da-fe held in Spain took place in Seville in 1781. The victim was María de los Dolores López, a woman of low social status, accused of faking revelations and to maintain sexual relations with her successive confessors ("she slept with them in her underwear, she was very often naked, and then they whipped her themselves because that was convenient for her salvation, although there is no record that there were complete acts", according to a friar familiar with the case). She was denounced by one of the confessors, who was convicted of having committed the crime of solicitation. The woman did not repent of her mistakes because according to her & # 34; nothing [of what she had done] was a sin & # 34; and she was sentenced to death. After the celebration of the auto-da-fe, which lasted twelve hours and in which the condemned woman appeared dressed in a sambenito and a crown painted with flames and devils, she was relaxed to the secular arm to be executed. She was given the vile club and then her corpse was thrown into a & # 34; great bonfire & # 34;.

It is usually said that the last auto-da-fe was held in Valencia in 1826, in which the teacher from Ruzafa, Cayetano Ripoll, was sentenced to be executed by hanging and later burned as a heretic, but at that time the Inquisition did not it existed because King Ferdinand VII had not reestablished it after its abolition by the liberals during the Triennium (1820-1823).

Development

In the Instructions issued in 1561 by the Inquisitor General Fernando de Valdés it was stated:

When the proceedings have been completed and the judgements have been established, the inquisitors shall set a public holiday to celebrate the self of faith; the date shall be communicated to the canons and to the municipal authorities and, if any, to the president and to the auditors of the court of justice, to invite them to attend the ceremony. Inquisitors will try not to start too late, so that the execution of the relaxed can be carried out day and without incident

The autos-da-fe were held on Sundays or holidays, because, according to Nicholas Eymerich's Manual of Inquisitors, "it is convenient for a large crowd to attend the torture and the torments of the guilty, so that fear may separate them from evil". "It is a show that fills the attendees with terror and a terrifying image of the Last Judgment. Well, this is the feeling that should be inspired". On the other hand, "the presence of the chapters, the churches and the magistrates gives greater splendor to the ceremony".

The preparations began a month before the set date because the dais had to be built in a public square or in a temple, with benches for the condemned so they could be seen by the crowd, a platform for the authorities, and bleachers. for viewers. It was also necessary to prepare the sanbenitos that the condemned would wear, the effigies of those who had fled or died, the banners and the ballot boxes that contained the sentences. In addition, the hangings and sometimes the awnings had to be arranged to provide shade for the attendees. All this involved a large sum of money, so the Inquisition, whose finances were never very buoyant, always had difficulties organizing them, and could not always count on the financial help of the municipalities where they were held. The consequence of all this was that "over time, autos-da-fe tended to become increasingly rare".

A few days before its celebration, a public proclamation was read in which the population was invited to attend the auto-da-fe. In Madrid in 1680, the town crier read the following in the squares and streets:

The inhabitants of Madrid, seat of the court of His Majesty, are informed that the Holy Office of the Inquisition of the Villa and Kingdom of Toledo will hold a public self of faith in the Plaza Mayor on Sunday, June 30; on this occasion, the sovereign Pontiff gives special graces and indulgences to all who attend.

At two in the afternoon the day before, the procession of the Green Cross began, accompanied by the banner of the Holy Office, which was carried by an important person —in the auto de fe of 1680 it was carried by the Duke of Medinaceli, & #34;prime minister" of Charles II. Behind him paraded the relatives, commissioners and notaries of the Inquisition, as well as representatives of the regular and secular clergy. The purpose of the procession was to take the Green Cross and the banner of the Inquisition to the place where the auto-da-fe was to be held the following day. The cross was covered with a black veil and "family members and nuns kept vigil all night, protected by a detachment of soldiers".

At dawn on the day of the auto-da-fe, the procession of the White Cross began, so called because it was headed by a cross, also called the bramble, which contained as a symbol some pieces of firewood that were going to be used in the bonfire where those sentenced to death would burn. Behind the White Cross, came the clergy, followed by the effigies ["life-size cardboard images", according to a contemporary account] of the condemned who had fled or died. before being judged -"whose bones were also brought in trunks, on which flames were painted", according to the account of the 1680 order-- and by the condemned carrying a candle in hand, headdresses with a crown or hood and dressed with the sambenitos that indicated the type of crime and the sentence.

As in a theatrical performance, the procession that formed to reach the place where the auto-da-fe was held had its rules regarding the order and distribution of the participants. The inmates were taken at dawn from the Inquisition prison to the chapel of the Holy Office from where the entire procession left formed. The cross was at the head of the entourage raised by the court prosecutor, who used to march on horseback. Behind him, on foot, walked the reconciled prisoners carrying candles as a sign of penance. Next were the Dominican friars, preceding the relaxed prisoners, that is, those sentenced to death. These prisoners were dressed in a kind of chasuble called sambenito, painted with scenes from hell, with terrible flames and figures of the condemned. On their heads they supported the coroza or capirote, a kind of cone also painted with infernal symbols, generally made of cardboard, which was grotesque and humiliating. Behind them were the so-called relatives of the Inquisition, which in some writings appear as "the eyes", and they closed the procession, first the lancers on horseback (or another military delegation) and then the representatives of the religious communities existing in the city.

As soon as the procession of the White Cross arrived at the public square or the temple where the auto-da-fe was to take place, and the condemned, the inquisitors and the authorities occupied the seats they had reserved, the act began with a sermon by a preacher dedicated to exalting the faith and attacking heresy. It also exhorted the unrepentant convicts to repent before being burned alive —if they did, they would be executed with a vile garrotte before being burned at the stake— since "a the inquisitors were very concerned about obtaining the conversion of all the condemned: no one should die without having confessed and having received the Eucharist', recalls Joseph Pérez. With these unrepentant special precautions were taken so that they could not address the public and they often appeared gagged.

After the sermon, the sentences were read. Each condemned man came forward to hear his own and if it was a reconciled person, he publicly abjured his mistakes and promised not to make them again. On that occasion, an inquisitor asked him about Catholic dogmas, and he, along with the public, answered: "Yes, I believe." Afterwards, various religious hymns were sung —Miserere mei, Veni Creator— and prayers were said, proceeding afterwards to discover the Green Cross that had remained covered with a black cloth. Finally, the inquisitor acquitted the reconciled and relaxed the secular arm of those sentenced to death so that the sentence could be pronounced and executed.

The auto-da-fe lasted several hours and could last the whole day, especially if it closed with the celebration of a solemn mass. There was some case in which it had to be suspended on Sunday night and resumed the following Monday.

"The following day, the sentences pronounced against the reconciled were carried out: lashes, a parade through the main streets to be exposed for all to see; those who had been sentenced to prison terms were taken to their cells".

An example: the auto-da-fé of the “Zugarramurdi witches” (Logroño, 1610)

On Sunday, November 7, 1610, "a great crowd of people" who also came from France to attend the event —it is estimated that thirty thousand people were present. they sported gold earrings and crosses on their chests—and several hundred members of religious orders. Next was the green Santa Cruz, insignia of the Inquisition, which was planted on top of a large scaffold. Later, twenty-one penitents appeared with a candle in their hands —and six of them with a rope around their throats to indicate that they had to be whipped— and twenty-one people with sanbenitos and large crowns with blades, candles, and ropes, indicating that they were reconciled.. Next, five people came out carrying statues of the deceased with relaxed seals, accompanied by five coffins containing their unearthed bones —they were two women and two men who had refused to admit that they were witches and warlocks, and another who had. she had done but that she would be burned for being one of the instigators of the sect. Next, four women and two men appeared, also with the labels of relaxed, who were going to be handed over to the secular arm to be burned alive because they had refused to admit that they were witches and warlocks. The procession was closed by four secretaries of the Inquisition on horseback accompanied by a donkey carrying a velvet-trimmed chest that kept the sentences, and the three inquisitors of the Logroño court, also on horseback. Once the defendants had settled on the scaffold and the inquisitors faced them, with the ecclesiastical state on their right and the civil authorities on their left, a Dominican inquisitor preached the sermon and then began the reading of the sentences by the inquisitorial secretaries. The reading lasted so long that the auto-da-fe had to be extended to Monday, November 8.

Classes of autos-da-fé

The following types of autos de fe are distinguished:

- General Self of Faith: is the one that was celebrated with a large number of prayers of all kinds (taxpayers or penitents relapses, confides repentant and penitentiated, etc.)

- Special Self of FaithIt is the one that was celebrated with some prayers without the apparatus or the solemnity of the general self of faith, so the authorities and corporations did not attend, but only the Holy Office and the ordinary royal judge in case of having any relaxed.

- Self of singular faithIt is the one that was celebrated with a single prayer, whether in the temple be in the public square according to the circumstances.

- Authentic: it is the self of faith that was celebrated within the chambers of the Inquisition court. It could be open doors for those who wanted to and to have a seat in the room or closed doors not to enter but the persons authorized to do so. In this second case it was sometimes with a fixed number of people outside the court and the dean inquisitor, or secret ministers, and then only the secretaries attended.

Contenido relacionado

Annex: Chronology of Chile

28th century BC c.

International Civil Aviation Organization