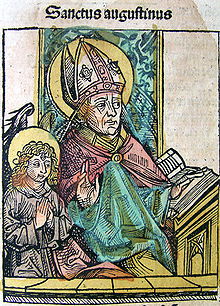

Augustine of Hippo

Augustine of Hippo or Aurelius Augustine of Hippo (Latin: Aurelius Augustinus Hipponensis), also known as Saint Augustine (Tagaste, November 13, 354-Hippon, August 28, 430), was a Christian writer, theologian and philosopher. After his conversion, he was Bishop of Hippo in North Africa and led a series of struggles against the heresies of the Manichaeans, the Donatists, and Pelagianism.

He is considered the "Doctor of Grace", he was the greatest Christian thinker of the first millennium and, according to Antonio Livi, one of the greatest geniuses of humanity. A prolific author, he dedicated a large part of his life to writing on philosophy and theology, being Confessions and The City of God his most outstanding works.

He is revered as a saint by various Christian communities, including the Catholic, Orthodox, Eastern Orthodox, and Anglican Churches. The Catholic Church considers him the Father of the Latin or Western Church and on September 20, 1295 Pope Boniface VIII proclaimed him a Doctor of the Church for his contributions to Catholic doctrine, along with Gregory the Great, Ambrose of Milan and Jerome of Estridon. His liturgical feast is celebrated on June 15 and August 28.

Biography

Birth, childhood and adolescence

Saint Augustine was born on November 13, 354 in Tagaste, an ancient city in North Africa on which the current Algerian town of Suq Ahras sits, then located in Numidia, one of the provinces of the Roman Empire. Scholars generally agree that Agustín and his family were Berbers, an indigenous North African ethnic group.

Augustine and his family were heavily Romanized, speaking only Latin at home as a matter of pride and dignity. However, Augustine leaves some information about his awareness of his African heritage. For example, he refers to Apuleius as "the most notorious of us Africans."

Her father, named Patricio, was a small pagan landlord and her mother, the future Saint Monica, is set up by the Church as an example of a Christian woman, of proven piety and kindness, a self-sacrificing mother and always concerned about the well-being of her family, even under the most adverse circumstances.

Mónica taught her son the basic principles of the Christian religion and, seeing how the young Agustín strayed from the path of Christianity, she gave herself up to constant prayer in the midst of great suffering. Years later Agustín would call himself “the son of his mother's tears.” In Tagaste, Agustín began his basic studies, and later his father sent him to Madaura to study grammar.

Agustín excelled in the study of letters. However, he himself acknowledges in the Confessions that he was not a good student and that he should have been forced to study in order to learn (cf. Confessions 1,12,19). In any case, he showed great interest in literature, especially classical Greek, and possessed great eloquence. His first triumphs were set in Madaura and Carthage, where he specialized in grammar and rhetoric. During his student years in Carthage he developed a irresistible attraction to the theater. At the same time, he was very fond of receiving flattery and fame, which he easily found in those early years of his youth. During his stay in Carthage he displayed his rhetorical genius and excelled in poetic contests and public contests. Although he was carried away by his passions, and openly followed the impulses of his sensual spirit, he did not abandon his studies, especially those of philosophy. Years later, Agustín himself made a strong criticism of this stage of his youth in his book Confessions .

At the age of nineteen, reading Hortensius by Cicero awakened in Augustine's mind the spirit of speculation and thus he devoted himself fully to the study of philosophy, a science in which he excelled. During this time the young Agustín met a woman with whom he maintained a stable relationship for fourteen years and with whom he had a son: Adeodato.

In his tireless search for an answer to the problem of truth, Augustine passed from one philosophical school to another without finding a true answer to his concerns in any. He finally embraced Manichaeism, believing that in this system he would find a model according to which he could guide his life. Several years he followed this doctrine and finally, disappointed, he abandoned it, considering that it was a simplistic doctrine that supported the passivity of good in the face of evil.

In great personal frustration, he decided, in 383, to leave for Rome, the capital of the Roman Empire. In Agustín's departure to Rome there was an intellectual motivation and to discover new horizons, but, mainly, what pushed him to travel definitively is the fact that he found out that the students in Rome were much more educated and respectful of teachers than those he taught in Carthage (cf. Confessions 5,8,14). Her mother wanted to accompany him, but Agustín deceived her and left her ashore (cf. Confessions 5,8,15).

In Rome he became seriously ill. After recovering, and thanks to his friend and protector Symmachus, prefect of Rome, he was appointed magister rhetoricae in Mediolanum, present-day Milan.

Augustine, as a Manichaean and imperial orator in Milan, was the oratorical rival of Bishop Ambrose of Milan.

Conversion to Christianity

It was in Milan where the last stage before Augustine's conversion to Christianity took place. There, he began to attend Bishop Ambrosio's liturgical celebrations as a catechumen, being admired by his preaching and his heart. Ambrosio introduced him to the writings of Plotinus and the epistles of Paul of Tarsus and thanks to these works he converted to Christianity and decided to definitively break with Manichaeism.

This news filled his mother with joy, who had traveled to Italy to be with her son, and who took it upon herself to find a marriage for him in accordance with his social status and direct him towards baptism. Instead of choosing to marry the woman Monica had found for him, he decided to live in asceticism; decision to which he arrived after having known the Neoplatonic writings thanks to the priest Simpliciano and the philosopher Mario Victorino, since the Platonists helped him solve the problem of materialism and the origin of evil.

Bishop Ambrosio offered him the key to interpreting the Old Testament and finding the source of faith in the Bible. Finally, reading the texts of Saint Paul helped Augustine to solve the problem of mediation —linked to that of the Communion of Saints— and that of divine Grace. According to Agustín himself, the decisive crisis prior to conversion occurred while he was in the garden with his friend Alipio, reflecting on Antonio's example, when he heard the voice of a child from a neighboring house saying:

Tolle legeTake and read

and, understanding it as a divine invitation, he picked up the Bible, opened it to the letters of Saint Paul and read the passage.

No comilones and drunkenness; no lust and shame; no rivalries and envy. Reveal yourselves more of the Lord Jesus Christ and do not worry about the flesh to satisfy his lusts.Rom. 13, 13-14.

At the end of this sentence all shadows of doubt faded.

In 385, Augustine converted to Christianity.

In 386, he devoted himself to the formal and methodical study of the ideas of Christianity. He resigned from the chair and withdrew with his mother and some of his companions to Casiciaco, near Milan, to dedicate himself completely to study and meditation.

On April 24, 387, at the age of thirty-three, he was baptized in Milan by the holy Bishop Ambrose. Already baptized, he returned to Africa, but before embarking, his mother Monica died in Ostia, the port near Rome.

Monasticism, priesthood and episcopate

When he arrived in Tagaste, Agustín sold all his possessions and distributed the proceeds to the poor. He withdrew with some companions to live on a small property to live a monastic life there. Years later, this experience was the inspiration for his famous Rule. Despite his search for solitude and isolation, Agustín's fame spread throughout the country.

In 391 he traveled to Hippo (Hippo Regius, modern Annaba, in Algeria) to look for a possible candidate for monastic life, but during a liturgical celebration he was chosen by the community to be ordained a priest, because of the needs of Bishop Valerius of Hippo. Agustín accepted, after resisting, this choice, although with tears in his eyes. Something similar happened when he was consecrated as a bishop in 395. He then left the monastery for laymen and settled in the episcopal house, which he transformed into a monastery for clerics.

Augustine's episcopal activity was enormous and varied. He preached and wrote tirelessly, argued with those who went against the orthodoxy of the Christian doctrine of that time, presided over councils and resolved the most diverse problems that his faithful presented to him. He faced Manichaeans, Donatists, Arians, Pelagians, Priscillianists, Academics, etc. He participated in the regional councils III of Hippo in 393, III of Carthage in 397 and IV of Carthage in 419, in the last two as president and in which the Biblical Canon that had been established by Pope Damasus I in Rome was definitively sanctioned. in the Synod of 382.

Already as bishop, he wrote books that position him as one of the four main Latino Church Fathers. Agustín's life was a clear example of the change he achieved by adopting a set of beliefs and values.

Death

Augustine died in Hippo on August 28, 430 during the siege to which Gaiseric's vandals subjected the city in the context of the invasion of the Roman province of Africa. His body, at an uncertain date, was transferred to Sardinia and, around 722, to Pavia, due to the expansionist threat of the Islamic world through the Mediterranean as well as the North African coast, to the basilica of San Pietro in Ciel d&# 39; Gold, where it rests today.

The legend of the encounter with a child by the sea

A medieval tradition, which includes the legend, initially narrated about a theologian, who was later identified as Saint Augustine, tells the following anecdote: one day, Saint Augustine was walking along the seashore, next to the beach, giving turned on its head many of the doctrines about the reality of God, one of them the doctrine of the Trinity. Suddenly, looking up, he sees a beautiful boy, who is playing in the sand. He takes a closer look and sees that the boy runs to the sea, fills the bucket with sea water, and returns to where he was before and empties the water into a hole. The boy does this over and over again, until Agustín, filled with great curiosity, approaches the boy and asks: "What are you doing?" And the boy answers: "I am taking all the water out of the sea and I am going to put it in this hole." And Saint Augustine says: «But, that is impossible!». To which the child replied: "It is more difficult for you to understand the mystery of the Holy Trinity."

The legend is inspired at least by Augustine's attitude as a student of the mystery of God.

Doctrine

Reason and faith

Augustine, predisposed by his maternal faith, approaches the biblical text, but it is his mind that cannot penetrate inside. In other words, for Augustine, faith is not enough to access the depths of the revelation of the Scriptures.At the age of nineteen, he turned to rationalism and rejected faith in the name of reason. However, little by little he changed his mind until he reached the conclusion that reason and faith are not necessarily in opposition, but that their relationship is complementary. Faith is an initial and necessary condition to penetrate the mystery of Christianity, but not a final and sufficient condition. Reason is necessary. According to him, faith is a way of thinking agreeing, and if thought did not exist, faith would not exist. That is why intelligence is the reward of faith. Faith and reason are two fields that need to be balanced and complemented.

To successfully carry out the conciliation operation between the two, it is essential to specify their characteristics, their scope of application and the hierarchy (faith wins over reason, since it is supported by God) that is established between them. As on many other occasions, it is in the biblical text where Augustine finds the starting point to support his position.

Commenting on a fragment of the Gospel of John (17,3), Augustine says:

The Lord, with his words and actions, has exhorted those who have called salvation to have faith in the first place. But then speaking of the gift that he should give to the believers, he said, "This is eternal life, that they believe," but, "This is eternal life, that they may know you, the one God, and the one you have commanded, Jesus Christ."Agustín de Hipona

This position is situated between fideism and rationalism. To the rationalists he replied: Crede ut intelligas ("believe to understand") and to the fideists: Intellige ut credas ("understand to believe"). Saint Augustine wanted to understand the content of the faith, demonstrate the credibility of the faith and deepen his teachings.

Interior

Augustine of Hippo anticipates Descartes by maintaining that the mind, while it doubts, is aware of itself: if I deceive myself, I exist (Si enim fallor, sum). As the perception of the external world can lead to error, the path to certainty is interiority (in interiore homine habitat veritas), which through a process of illumination meets the eternal truths and the same God who, according to him, is in the most intimate of each one.

The eternal ideas are in God and are the archetypes according to which he creates the cosmos. God, who is a community of love, comes out of himself and creates out of love through rationes seminals, or germs that explain the evolutionary process that is based on a constant creative activity, without which nothing would subsist. Everything that God creates is good, evil has no entity, it is the absence of good and the undesirable fruit of man's freedom.

Conception of time

Saint Augustine paradoxically expresses the perplexity generated by the notion of time: «What is time? If no one asks me, I know. If I have to explain it, I don't know anymore.” Based on this perplexity, he attempts a fruitful ontological reflection on the nature of time and its relationship with eternity. From the fact that the Christian God is a creator but not a created God, it follows that his temporal nature is radically different from that of his creatures. According to the answer he gave to Moses, God defines himself as:

And God said to Moses, "I am the one who I am," he added, "Thus you will say to the Israelites, "I am sent to you."Exodus3,14

Saying this is equivalent to defining yourself regardless of any quality, which is equivalent to ignoring change. Therefore God is outside of time while human beings are structurally temporal entities.

Influenced by Neoplatonism, Augustine separates the world of God (eternal, perfect and immutable), from that of creation (dominated by matter and the passage of time, and therefore mutable). His analysis leads him to the asymmetry of time. This asymmetry comes from the fact that everything that has already happened is known to us because we have experienced it and it is easy for us to remember it in the present, something that does not happen with a future that is about to happen. For Saint Augustine, God created time ex nihilo along with the world and subjected its creation to the course of that time, hence everything in it has a beginning and an end. He, on the other hand, is outside of all temporal parameters.

"I measure time, I know; but I do not measure the future, which is not yet; nor do I measure the present, which does not extend through any space; nor do I measure the pretery, which no longer exists. What then is what I measure?”(Confessions, XI, XXVI, 33)

Augustine rejects the identification of time and movement. Aristotle defines time as an arithmetic resource to measure a movement. Augustine knows that time is duration, but he does not accept that it is identified with a spatial movement. The duration takes place within us and is the result of the ability to foresee, see and remember the events of the future, present and past. Agustín comes to the conclusion that the seat of time and its duration is the spirit. It is in the spirit that the sensation of duration (long or short) becomes effective, of passing time, and it is in the spirit that the duration of time is measured and compared. What is called future, present and past are nothing but expectation, attention and memory of the spirit, which has the ability to foresee what will come, look at it when it arrives and keep it in memory once it has passed.

“And more properly it would be said: “Three are the times, present of the past, present of the present and present of the future.” Because these three presences have some being in my soul, and I only see and perceive them in it. The present of past things is the present memory or memory of them; the present of the present things is the present consideration of something present; and the present of future things is the present expectation of them.”(Confessions, XI, XX, 26)

Original Sin

Augustine taught that the sin of Adam and Eve was an act of foolishness followed by pride and disobedience to God. The first couple disobeyed God, who had told them not to eat from the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil (Gen 2:17). The tree was a symbol of the order of creation. Egocentrism made Adam and Eve eat of it, so they did not recognize or respect the world as it was created by God, with its hierarchy of beings and values.

They would not have fallen into pride and lack of wisdom, if Satan had not planted in their senses "the root of evil". His nature was wounded by concupiscence or libido, which affected human intelligence and will, as well as the affections and desires, including sexual desire. Augustine used Cicero's Stoic concept of the passions to interpret Paul's doctrine of the original sin and redemption.

Some authors perceive Augustine's doctrine as directed against human sexuality and attribute his insistence on continence and devotion to God as a result of Augustine's need to reject his own highly sensual nature, as described in the Confessions. Augustine declared that "for many, abstinence is easier than perfect moderation".

His system of grace and predestination prevailed for many centuries, although not without strong opposition, and underwent, through a scholastic elaboration, substantial changes to save free will; and finally it reappeared in the conception of the spiritual life modeled by Luther and the other teachers of the Reformation.

Fight against heresies

When Augustine was born, not even fifty years had passed since Constantine I had legalized Christian worship. After the establishment of Christianity as the official religion of the empire by Theodosius I the Great, multiple interpretations of the gospels arose.

According to Augustine, heresy is the misunderstanding of the faith, which is why it is a problem of a rational nature, although not every error is. In his treatise Heresies he distinguishes 88, but the main ones he had to deal with were: Manichaeism, Donatism, Pelagianism and Arianism.

- The struggle against the doctrine of the Manicheans occupies an important part within their apologetic works, because many believed that Mani's teachings shed light on Scripture. With the number of apocryphal Gospels, manifoldism made many Christians maintain a dualism between these two beliefs. Augustine wrote one of his main anti-manique texts to Bishop Fausto. Augustine criticizes the doctrine of this heresy by saying that it represented a distortion of external origin to the Christian message.

- Donatism was an inner threat. After the Edict of Thessalonica, a group of believers who were overthrown by Bishop Donato were separated from the Church, who were accused of being condescending with the lapsi. This struggle was a priority for doctrinal and political reasons, as its belligerent character put the Catholic Church in North Africa at risk. Donatism is like an excess of faith, since it does not admit in the Church those who in the persecutions refused faith, thus separating the institution of the followers. For Augustine instead the Church is made up of men, who are imperfect, but not because of it when they "fall" (lapsi) lose validity the sacraments received. Donatists conceive a Pure Church of believers who seek perfection and should not readmit the renegades. Augustine, despite using repressive measures to lapsiHe advocated for acceptance and forgiveness and thinks they do not need to be re-admitted, since they continue to belong to the Church. High tensions, as with the circumcellions, led to the prohibition of donaticism in Cartago with an imperial Christian named Marcelino in 411.

- Pelagianism posed a problem of rational interpretation about the value of the actions performed by the believer as merit to gain salvation. Augustine accused the Pelagianism of not believing in God's free love. Salvation for him is not an exclusive merit of man's will in performing good works, but also plays a very important role in grace. Augustine failed to make Pelagianism disappear in life, although his contributions on this subject were decisive during the Council of Ephesus, held a year after his death.

The conception of history

Augustine's philosophy of history describes a process that affects the entire human race. It is a universal history made up of a series of successive events that move towards an end through divine providence.

He also describes the different moments in history: first, creation, followed by the fall caused by original sin, in which the devil introduces degradation into the world: God offers paradise, but the individual he chooses to misuse his freedom, disobeying him. He is followed by the announcement of the revelation, and the incarnation of the son of God. The last stage is achieved by the redemption of the individual by the Church, which is the sixth of the ages of the human being.

Unlike the cyclical conception of time and history characteristic of Greek philosophy, Augustine bases his representation of history on a literal, progressive and finalist conception of time. History has had a beginning and will have an end in the Last Judgment, and it is divided into six ages, inspired by the six days that God used to create: the Six Ages of the world, delimited by the creation of the world, the flood universal, the life of Abraham, the reign of David (or the construction of the temple in Jerusalem, by Solomon), the captivity in Babylon and, finally, the birth of Christ, which inaugurates the sixth age. The latter continues until the second coming of the Messiah to judge men at the end of time. Humanity has begun a new stage, in which the Messiah has come, and has given hope of resurrection: with Christ, the old human ends, and spiritual renewal begins in the new human. The consummation of history would be to reach the end without end: eternal life, in which peace will reign, and there will be no more fighting. No one will rule over anyone, and infighting will end. His thesis is that since the coming of Christ we live in the last age, but only God knows the duration of this age.

Saint Augustine tries to show that human freedom must be reconciled with the intervention of God, who does not coerce the individual, but helps him. The action of the individual exercises freely, framing individual morality in a community morality. The historical process of the human being can be explained through the dialectical struggle, the conflict, between the two cities of the world, which will eventually reach harmony.[citation required]

The City of God

The City of God is one of the thinker's most important books. It is mainly a theological work but also one of deep philosophy. The first part of the book seeks to refute the pagan accusations that the Church and Christianity were to blame for the decline of the Roman Empire and more particularly for the sack of Rome. He predicts the triumph of a Christian State supported by the Church and defends the theory that history makes sense, that is, that there is divine Providence for nations and individuals.

As the book progresses, it becomes a vast cosmic drama of creation, fall, revelation, incarnation, and eternal destiny. According to Augustine, views of class and nationality were trivial compared to the classification that really matters: whether one belongs to "God's people".

Since creation, history has coexisted with the «earthly city» (Civitas terrea), turned towards selfishness; and the “City of God” (Civitas Dei), which is being realized in the love of God and the practice of the virtues, especially charity and justice. Neither Rome nor any State is a divine or eternal reality, and if it does not seek justice it becomes a grand robbery. The city of God, which is also not identified with the Church of the present world, is the goal towards which humanity is heading and is destined for the just.

The Augustinian division into two cities (and two citizenships) will have a decisive influence on the history of the medieval West, marked by what has been called «political Augustinism». The Christian who feels called to be an inhabitant of the city of God and who orders his life in accordance with amor Dei cannot avoid being at the same time a citizen of a specific people. Whatever this people may be, they will never be able to fully identify with the ideal city of God, which is why the Christian will remain structurally divided between two citizenships: one of a strictly political nature, which is the one that links him to a city or a concrete state; and another that cannot stop being partially political, but that is also largely spiritual.

“True justice does not exist, except in that republic whose founder and ruler is Christ.”

The theory of the two cities raises how the Christian has to live: he must have his sights set on the ultimate goal of full heavenly citizenship, but without forgetting, at the same time, to give meaning to his passage through this earthly life, given that the story does not seem to have to come to an immediate end.

Theologically, The City of God is a very important work according to his vision of salvation history and for having embodied the key doctrines of Christianity such as creation, original sin, the grace of God, resurrection, heaven and hell.

Philosophically, by showing how philosophy serves as a value to build an exhaustive vision of Christianity, as well as by providing a general framework within which most of the political philosophy in the Christian West was made with a utopian vision, in such a way that he influenced Christian writers such as Bossuet, Fénelon, De Maistre, Donoso Cortés, among others.

Augustinian Theodicy

Saint Augustine was especially interested in the “problem of evil”, attributed to Epicurus, who had stated: “If God can, knows and wants to put an end to evil, why does evil exist?”. This fundamental fact becomes an argument against the existence of God, still used by atheists and critics of religions. The responses to the argument that attempt to rationally demonstrate the coherence of the existence of evil and God in the world, are called theodicy.

Augustine gave several answers to this question based on free will and the nature of God:

- Saint Augustine believes that God created all good. Evil is not a positive entity, then it cannot "be", as the Manicheans say, because according to Augustine, evil is the absence or deficiency of good and not a reality in itself. Saint Augustine takes this idea of Plato and his followers, where evil is not an entity, but ignorance.

- For St. Augustine the word "bad" is an absence of something. This does not have intrinsic properties. Evil is a system restriction itself. It is an internal dynamic restriction of the world. Augustine's argument says that when it feels that there is no sense in life there is a void, and that evil is given by its own decisions. The only way to get away from evil is to be filled with fullness. If God is this substance or source of primordial reality, then evil is the deprivation of substance by its own decisions. This means that evil does not exist substantially, but exists by the deprivation of good or of God.

- Augustine argues that human beings are rational entities. Rationality consists of the ability to evaluate options through reasoning, and therefore God had to give them freedom by nature, which includes being able to choose between good and evil. God had to leave the possibility of Adam and Eve to disobey him, which exactly happened according to the Bible. This is known as the defense of free will.

- For Augustine, God allowed natural evils because they are just punishment of sin, and although animals and babies do not sin, they are worthy of divine punishment, being the children heirs of original sin.

- Finally, Augustine suggests that the world should be seen as something beautiful. Although evil exists, it contributes to a general good greater than the absence of it, as well as musical dissonances can make a melody more beautiful.

Ethics

The concept of love is central to Christian theological doctrine, which alludes to the thematic core related to the figure of Christ. The concept of love in San Agustín is so preponderant that it has been the object of study by illustrious intellectual figures such as Hannah Arendt. For Saint Augustine:

love is a precious pearl that, if it is not possessed, nothing serves the rest of the things, and if it is possessed, everything else remains.

"Love and do whatever you want: if you shut up, shut up for love; if you shout, shout for love; if you correct, correct for love; if you forgive, forgive for love. The root of charity is within you; the root of that root cannot spring but good."

Augustine also formulated his own version of the biblical quote "love your neighbor as yourself" in the following way:

Cum dilectione hominum et hatred vitiorum

Which translated means "with love of humanity and hatred of sins," often quoted as "love the sinner but not the sin." Augustine led many clergymen under his authority on Hippo to free his slaves "as an act of mercy". Saint Augustine also said:

You made us, Lord, for You, and our heart will be restless until it rests on You.

For the saint, God created human beings for Him, and therefore human beings will not be whole until they rest in God. As for other Fathers of the Church, for Augustine of Hippo, social ethics implies condemnation of the injustice of wealth and the imperative of solidarity with the disadvantaged:

The riches are unjust or because you unjustly acquired them or because they themselves are injustice, because you have and another has not, you live in abundance and another in misery.Psalmos 48

Saint Augustine was insistent on the idea of justice. Upton Sinclair quotes Augustine in The Cry for Justice, a collection of quotes against social injustice:

The superfluities of the rich are the needs of the poor. Those who possess superfluities possess the goods of others.

Augustine of Hippo also defended the good of peace and tried to promote it:

To end the war by word and seek or maintain peace with peace and not with war is a title of greater glory than to kill men with the sword.Epistle 229

In The City of God, Saint Augustine attacks Roman tradition, including myths such as that of Lucrecia, a lady who, after being raped by the son of the last king of Rome, committed suicide by sticking a dagger. For the Romans, Lucrecia was the most worthy model of moral integrity. Not for Agustín, who considers that her death added a crime to another crime, since "whoever kills himself kills a man and, therefore, contravenes divine law."

Agustín, at various times in his works, will devote attention to lies. In On Lies, he classified lies as mischievous or humorous, and distinguishes the liar (who enjoys lying) from the liar (sometimes he does it unintentionally or to please). Like Kant, does not consider it lawful to lie to save a person's life.

“The capital lie and the first to be resolutely avoided is the lie in religious doctrine. [...]The second is the one who unjustly harms someone, that is, who harms someone, and takes no advantage of anyone. The third is the one that favors one, but it hurts another, even if it is not in clumsy body. The fourth is the one committed by the pure appetite of lying and cheating, which is the pure dry lie. The fifth is the one that is committed to wanting to please the conversation. The sixth is the one who takes advantage of anyone, without harming anyone. [...]The seventh is the one that, without harming anyone, favors any, except the case that the judge asks [...] The octave is the one who, without harming anyone, takes advantage of someone to avoid being cluttered in the body.”St. Augustine, Mendacio510-511.

Politics

As the influence of the Church increased, its relationship with the State became contentious. One of the first political philosophers to deal with this issue was Augustine of Hippo in his attempt to integrate classical philosophy into religion. He was powerfully influenced by the writings of Plato and Cicero, which were also the foundation of his political thought.

As a citizen of Rome, he believed in the tradition of a state bound by law, but as a humanist he agreed with Aristotle and Plato that the goal of the state is to enable its people to lead good and virtuous lives. For a Christian this meant living according to the divine laws sanctioned by the Church. Augustine thought that in practice there are few people who live according to these laws and that the majority live in sin. He distinguished between the city of God and the earthly city. In the latter, sin predominated.

For Saint Augustine, a theocratic model under the influence of the Church over the State is the only way to ensure that earthly laws are dictated with reference to divine ones, allowing people to live in the city of God, whether that "an unjust law is no law at all".

Having those fair laws is what distinguishes a state from a gang of robbers. However, Augustine further points out that even in a sinful earthly city, the authority of the state is capable of ensuring order through laws and that everyone has reason to desire order.

Without justice, what would kingdoms really be but bands of thieves?, and what are the bands of thieves if not small kingdoms? [...] For this reason, intelligent and truthful was the answer given to Alexander the Great by a pirate who had fallen into his power, for having asked the king why the sea was infested, with bold freedom the pirate answered: for the same reason why you infest the earth; but since I do it with a small trunk they call me a thief, and to you because you do it with formidable armies, they call you emperor.St. Augustine, The City of God, IV, 4.

Augustine adopted Cicero's definition of community as an argument against Christianity's responsibility for the fall of Rome.

Just war

The insistence on justice with its roots in Christian doctrine was also applied by Saint Augustine to war. He believed that all war is evil and that attacking and plundering other states is unfair, but he accepted that there is a "just war" waged for a just cause, such as defending the state against aggression or restoring peace, even though it must be resorted to. she with remorse and as a last resort. In Contra Fausto she justifies violence as a "necessary evil" to make heretics and pagans return to the straight path of faith, an argument that will be used from the IX by the papacy to legitimize the fight against the infidels, giving rise, later, to phenomena such as the crusades or the Inquisition.

Reception

Saint Augustine is of great importance in the history of European culture. The Confessions of him suppose a model of interior biography for many authors, who are going to consider introspection as an important element in literature. Specifically, Petrarch was a great reader of the saint: his description of his love states is linked to that interest in the inner world that he finds in Saint Augustine. Descartes discovered self-awareness, which marked the beginning of modern philosophy, copying its fundamental principle (cogito ergo sum/I think therefore I am), not literally but in meaning, by Saint Augustine (si enim fallor, sum/if I'm wrong, I exist: De civ. Dei, 11, 26).

On the other hand, Saint Augustine will be an important bridge between classical antiquity and Christian culture. The special appreciation that he has for Virgil and Plato will strongly mark the following centuries.

There are two main schools of Catholic philosophical and theological thought: the Platonic-Augustinian and the Aristotelian-Thomistic. The Middle Ages, until the XIII century and the rediscovery of Aristotle, will be Platonic-Augustinian.

The philosopher Bertrand Russell was impressed by Augustine's meditation on the nature of time in the Confessions, comparing it favorably with Kant's version:

"I myself am not in conformity with this theory, because it makes time something mental. But it is clearly a very skilled theory, worthy of serious consideration. I would go further and say that it is a great advance in regard to what is found in Greek philosophy. It contains a better and clearer exposure than that of Kant of the subjective theory of time—a theory that, since Kant, has been widely accepted among philosophers."Bertrand Russell, History of Western Philosophy

Augustine's analysis and criticism are still valid, as contemporary philosophers such as Hannah Arendt and Jacques Derrida are oriented, in their reflections, by the author of The City of God.

The figure of Agustín inspired different golden comedies within the popular subgenre of the comedy of saints. One of the most famous cases is that of Lope de Vega, author of El divino africano (ca. 1610), where the conversion of Agustín from Manichaeism to Catholic faith.

Augustine and science

According to the scientist Roger Penrose, Saint Augustine had a "brilliant intuition" about the space-time relationship, anticipating Albert Einstein and the theory of relativity by 1,500 years when Augustine affirmed that the universe was not born in time, but rather with time, that time and the universe arose at the same time. This claim of Augustine's is also rescued by Penrose's colleague Paul Davies.

Augustine, who had contact with Anaximander's ideas of evolutionism, suggested in his work The City of God that God could use inferior beings to create man by infusing him with a soul. He thus defended the idea that despite the existence of God, not all organisms and inert things came out of Him, but rather some suffered evolutionary variations in historical times from God's creations.

Works

St. Augustine was a prolific author who left a large number of works, written from 386 to 419, dealing with various topics. Some of them are:

Veneration

Saint Augustine is venerated in the Catholic Church, the Orthodox Church, the Eastern Orthodox Churches and some Lutheran Churches as he appears in the Lutheran liturgical calendar.

Contenido relacionado

Pierre de Fermat

Kingdom of macedonia

Ontology