Asturleones language

The Astur-Leonese language is a Romance language known by various gluttonists as Asturian, Leonese or Mirandés (traditionally each zone or region has used a localism to refer to this language, in this way we can find different denominations such as cabreirés, senabrés, berciano, paḷḷuezu, pixueto, etc.).

Phylogenetically, Astur-Leonese forms part of the Western Ibero-Romance group and arises from the peculiar evolution that Latin underwent in the kingdom of Asturias (later called the kingdom of León). The Astur-Leonese group is subdivided into three linguistic varieties (Western, Central and Eastern) that vertically trace a north-south division from Asturias to northern Portugal, thus forming the Astur-Leonese linguistic domain. The montañés in the east and Extremaduran in the south are linguistic varieties with transitional traits with Castilian rule.

Historical, social and cultural aspects

Origin

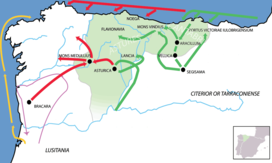

The Astur-Leonese language has its origins in Vulgar Latin, transmitted mainly by the Roman legions based in Asturica Augusta and Legio VI. The supplanting of the Asturian language by this other was slow but unstoppable, since the use of the imperial language was the key that opened the doors to obtain many rights and freedoms, among them the most important: Roman citizenship. However, as in the rest of the peninsula, it was not until the establishment of the Germanic kingdoms (Visigoths) that Latin, more or less modified, finally established itself as the only and common language on the peninsula.

In the Asturian languages, markedly conservative traits concur, doubly, such as the maintenance of the groups AI, AU and MB together with other breakers of the Latin system, such as the transformation of the original vocalism towards a system of diphthongs. This is explained by the nature of the meeting in the territory of the Astures of two very different romanization processes: the one coming from Baetica and the one coming from Tarragona. Kurt Baldinger, Krüger, Menéndez Pidal and other authors have highlighted the importance of the Sella River as the linguistic limit of these two worlds. This is how Menéndez Pidal points out in Origenes del español: “The limit of f and h towards the sources of the Sella river is, therefore, a very old and stationary or almost stationary limit”. Bética, with its flourishing civic culture and its active cultural life, would oppose the military and vulgar character of the Tarraconense. Portuguese: maintenance of the final -U and the groups AI, AU, MB. This conservative character is reflected in certain words that are only present in the Northwest of the peninsula, which were already in disuse in the time of Cicero: thus 'fabulari' (to talk, talk) in front of 'parlare' (parlare, parlar), for 'quaerere' (to want) in front of 'volere' (to fly, vouloir), 'percuntari' (to ask) versus 'questionare', campsare (to tire), etc. On the other hand, the peripheral situation of the peninsular northwest would also determine that, once Latin was adopted, many Latin words that only survive as popular words in the Northwest would be conservatively maintained; so e.g. eg, the lat. culmus 'stem' is colmo in Portuguese, cuelmu in Asturian (see the forms put together by Corominas and FEW; because of the diphthong ue, which can only be due to a ŏ, assumes Corominas a Celtic 'kŏlmos', ZCPhil 25, 1956, p 42); Silva Neto gathers no less than 51 examples (p. 269 ff.; regarding ATRIUM see especially p. 353, note 8). Malkiel has shown that the lat. ALIQUIS “as a pronoun took refuge in a remote and conservative district: the NO. and W. of the Iberian Peninsula”.

Along with these conservative traits, there are others that present a markedly innovative character and that can only be explained by the resistance of the peoples of the North to Romanization, a conflict situation that we know today through the Cantabrian wars. These two trends, together with the expansion and subsequent decline of vernacular languages such as Basque, after the period of instability that followed the Germanic invasions, will determine the special linguistic evolution of the northwest of the peninsula. In the vocabulary there are thus pre-Roman elements from the most diverse layers, which survived the late Romanization of this area, and even pre-Indo-European elements that had only been preserved in place names.

The appearance of the Romance language in the Kingdoms of Asturias and León

In the 8th century century, the language of the Church and administration was so different from that spoken that one can already Think of two different systems: Latin and Romance. This evolution over time gave rise to the appearance of the first documents with expressions written in the Romance language in the middle of the X century. in various monasteries in Asturias and León. For example, the manuscript of the Nodicia de Kesos, where the Romance of that time replaces Latin in a routine act of buying and selling. The language of this writing is considered the prelude to Astur-Leonés. From Latin written in the X and centuries ="font-variant:small-caps;text-transform:lowercase">XI, very altered by the local Romance language, there is a very important collection of documents from the monasteries of Sahagún, Otero de Dueñas and the Cathedral of León.

According to Hanssen's criteria, which is not currently shared by the linguistic community, Leonese would only be Castilian spoken by individuals whose primitive dialect was Galician and who were Castilianized. This would explain, according to this author, the maintenance of - o- on the one hand, and on the other, the false application of the diphthong to words that in Spanish repudiate it on the other. Staaf is shown in this same sense. Menéndez Pidal would be able to demonstrate the existence of assumptions of diphthongization prior in time to the Castilian predominance, establishing the existence of his own and different criteria in order to translate the short Latin vowels -e- and - o-. For this author, the Astur-Leonese group would be a consequence of the isolation of the most western dialect modalities of the primitive central peninsular Romance as a consequence of the irruption of Castilian and the late Latinization of primitively Basque-speaking groups, which would break the primitive linguistic unity of the peninsula. As Menéndez Pidal points out in Orígenes del Español: ...the Castilian differential note works like a wedge that, driven into the North, breaks the old unity of certain common Romanesque characters that had previously spread throughout the peninsula and penetrates as far as Andalusia, splitting the old dialectal uniformity, breaking up the primitive linguistic characters from the Duero to Gibraltar, that is, erasing the Mozarabic dialects and to a large extent also the Leonese and Aragonese, and increasingly expanding its action from North to South to implant the special linguistic modality born in the north of Cantabria. The great expansion of the Spanish language did not take place until after the XI century, that is, after the date we have mentioned. imposed as a term to this study. According to the traditional thesis followed by Menéndez Pidal, the languages of the Astur-Leonese group would come to be the result (dialectal in Menéndez Pidal's expression) of an unfinished process of linguistic integration of the peninsular languages, in which Astur-Leonese would be a sample of the primary substrates. of this process. In this sense, Menéndez Pidal considers Leonese or Asturleonese, together with Castilian in its different varieties, Mozarabic and Navarro-Aragonese, one of the four dialect groups within the Iberian Peninsula that contribute to the formation of the language Spanish. For Menéndez Pidal, the Astur-Leonese language would be the result of the isolation of the most western dialectal varieties of the central peninsular Romance due to the irruption of Castilian, which would put an end to the primitive geographical continuity of certain common features of the East and the West.

Evolution of the language during the Middle Ages

The language used in the writing of all kinds of acts will progressively be Asturleonese in the territory of the Kingdom of León. It is therefore a language that is used at an administrative, public and private level: wills, appraisals, Sales letters, court rulings, everything in this period is written in Asturian Romance. Legal texts are translated from Latin, such as the Fuero juzgo (known in the kingdom of León as Livro Iudgo), the procedural treaty Flowers of Law (initially written in Spanish by the master Iacobus between 1252 and 1274) and the privileges granted to various cities León (1017), Alba de Tormes (1140), Oviedo (1145), Avilés (1155), Campomanes (1247), Benavente (1164 and 1167), Zamora (1289), Ledesma (1290) or Salamanca (1301). In this period, an approach towards achieving a linguistic homogenization that could have a chancellery use is perceived. Outside the administrative and features of the Leonese XIII century in manuscripts such as the Libro de Alexandre or the Dispute between Elena and María, probably introduced by copyists from Leon.

about contests that lie between the Concello de Abilles and the Concello de Oviedo, in reason that’l Concello de Oviedo dizian that’l Concello de Abilles forged ye to take a quantia of bacons to sos that they will come from the Rochela, ye others in reason that’l Concello de Abilles di Allamos that’l Concello de Oviedo fezieron prender a Roy Nicolas ye asso fillo por prinda de los pannos que prindaron los de Abilles a los mercadores vezinos de Oviedo. We send per manda ye so sorry of the fiadoria, that they are told in the proof, that’l Concello de Abilles then hand over to the timelines of Oviedo the pans that-llos prindaron. Others if we send that’l Concello de Oviedo fagan then release Roy Nicolas ye a so fillo in stew that they can go around their houses. Others if we send all the other demands and quexumes that auian the Concellos ye sos timens against each other for whatever reason binds the day that this letter and the date that are all taken away. τ por tal que este sea firme ye non uenga en dolda nos rogamos que feziessen fazer d'esti fecho una carta parte. This foe fecho in Oviedo twenty-three days from Ochobre. It was a thousand CCC twenty-seven years. 1289, October 23. A.A.A., not 23.

Yo María Pérez, muller de Garçía Maquila, nen per fear nen per forçia, fago carta de donaçión a vos María Garçía, mia criada, cuéllovos por filla ye dovos todo quanto me he, ye nomadamentre vos donto yo gané del dicho mio husband, ye les enpennes que yo fizi de Roy Gonçáliz This you commo de suso said ye all give up in pure donaçión because you raised ye you rub some things of what you would not pay, ye because I pay clear ye de bona veluntat devos-llo dar, so lluogo (afternoon) per this letter vos do el jur ye la propriedat. Et porén renunçio todos quantos derechos, llees, (laws) uses ye costumes. Date the letter vinti e çinco dies de abril, era de mille ye trezientos ye trinta ye dos annos. Don Miguel, for God's graçia bishop of Oviedo. The king's greatest man in the land of Lleon and Asturies. I María Pérez de suso said this letter that I sent fazer oy lleer with my hands proprias lla rovro ye confirm it. 1294, April, 25. A.M.S.P.O., F.S.V. doc. n.o 827.

Rodericus peels grace of God Bishop of Oviedo with bestowal of the Dean ye of the Cabidro of Sant Salvador fazemos pleyto with inhabitants of Campomanes. Make sure that every one of you has dared to give each one anno to the Bishop, II released from each suolo. Ye of every orth VI money. Ye all the suolos (soils) ye the orths of the inhabitants alike both the one commo el otru, assi commo fo de viello. Ye by nuncio deve adar el omne del Re que-hy morar II soldos ye el fillo dalgo IV soldos. Ye if the Bishop for a Campomanes once every anno.dalle these moneys ye si elli non for hy-dallos every feast of Sant Iohan to whom elli send-hye. Quantos morarent en Campomanes non devent atraher comenderu nen sennor quien destorve elos derechos del Obispo ye-ssi alguna contra ellos for, assi merino commo otru omne qualquier, nos dallos vocaleru quien razone so pleyto por so cost dellos. Ye nos, Concello de Campomanes grant isti pleyto ye this karta assi commo ye escripta ye nunciada. 1247, October. Oviedo.A.C.U. Series A. Folder 7, no 6.

auemos una casa enna Rua que nos pertenez pus Don Iohan que fo mio husband ye father de aquestos mios fillos, ye (y) the other half of the house (en) of Santa María de la Vega. 1244, January 14. A.M.S.P: F.S.M.V. Leg. 1. not 16

assi that from isti day to apron our iur be fora ye on your iur be entrance ye fagades ende your veluntat. If you object to venier oversto, we are awarded a salvalla ye guarilla per nos. 1248, June 16. A.M.S.P: F.S.M.V. Leg. 1. not 17

dovos all'l so inherited that to my own for such condition that you pay the fingers (debts) that I devo (ye) defying that no man nen mullier of mine linnage nen de estranno that you non embargue this you do. 1259, October 6. A.M.S.P: F.S.M.V. Leg. 1. not 23

...euedes put hy omne que ande hy [and you must put in there a man who walks] of uuhand, que non es morador de quilos [no morador de aquellos] nen dela alfoz de Nora anora [ni del Alfoz de Nora a Nora] τ que ande hy [that walks there] well τ lealmientre [well and loyally]. No.no [read damage] ho malfetria fezier [or malfetria (made evil) dociere] enna [read eña] alfoz, queYou thatignies yelomelloredes [you better] by the. by forum τ by right. I do [And if] dientro.these. V annos [reading years] anything you did [get it] because this approach that you takenWe give to you as ia said ye [yet said] uos fosse embargado ho contrada we grant to saluarla τ guarirla Auos con derecho. Hie por such [and by such] that all this is Creudo et que non uenga endolda [in doubt] We sent our Iuyzes nomnados Don Nicolao. guion. τ don pedro fernandiz uermudiz que posiessent enesta Carta el nuestro seello del concello en testemunNo.. 1257. A.A.O. C-21, not 14.

who omne kills, if he does not defy him in council, he dies for him; if fur niego e non podier sign, he cries for his pair; and if he falls, enforquenllo, ['who kills a man without being challenged in the council, dies for him; if he denied it and could not prove it, to prove his innocence in a struggle, and if he loses that he is hanged']. Ledesma Fort.

The traditional thesis postulated by Menéndez Pidal based on the claim of the hegemonic role of Castile in the generation of the Spanish language and on the vision of Castilian as the first language with its own literature, makes the testimony of the first texts annoying. literary, not always written in Spanish. These interpretations are reflected when analyzing Elena y María, due to the non-subjection of the language of this poem to the regularity expected by Pidal in the manifestation of diphthongs, something common in phonetic features, which he uses as an argument to downplay the literary importance of the Leonese language, despite the fact that he himself recognizes these same irregularities in the Mío Cid. This vision, not currently shared by the linguistic community, is reflected in the words of Pidal when he said that literary texts and 'leonese' they do not agree on his testimony; neither those nor these reflect with sufficient fidelity the spoken Leonese dialect; and in literary texts, especially, two influences can be seen fighting, literary too, and completely opposite, the Galician-Portuguese and the Castilian, which were not exercised in the same way, much less in the spoken language. The spoken language maintained until today its own characters well harmonized with each other, in which the gradual transition in space is observed, from the Galician-Portuguese features to the Castilian ones; Instead of this gradual transition, the written texts show us an antagonistic mixture, since Leonese literature, lacking in personality, wavered between the two centers of attention that indisputably surpassed it.

Diglossia and official status of the Spanish language

Already included in the XIV century the Leonese territories under the Castilian orbit, and in the time in which they could be Given the right circumstances for its development as a language of prestige and culture, Castilian will replace Leonese in these areas, as in neighboring Galicia, postponing it to oral use, as happened before with Latin. Consequently, there will be a significant distance between the spoken language and the written language, Spanish.

From the 15th century to the XVIII this period can be referred to as that of the dark centuries, where, as in other areas of the Iberian Peninsula and Europe, the languages of the resulting states, in a process of centralization, to marginalize those of the rest of those territories, removing linguistic and cultural homogenization that endangers the existence of some languages and leads to their dialectal fragmentation.

In the Modern Age, production in Leonese was focused on the literary field where authors such as Juan del Enzina, Lucas Fernández or Torres Naharro published works using Leonese, especially those focused on eclogues.

From the XVII century we find manifestations of the Asturian language, through an archaic literature, in authors such as Antón de Marirreguera or Josefa Jovellanos (sister of the enlightened Gaspar Melchor de Jovellanos) who, by using these stylistic resources typical of the so-called rustic speech, will recover elements typical of the Asturian language. This literary tradition was continued during the XIX century by authors such as Xuan María Acebal, José Caveda y Nava, Teodoro Cuesta, Pin de Pría or Fernán Coronas. Regarding this literature, the Swedish linguist Åke Munthe points out «Reguera must be considered the creator of this literature, which I would call bable, and of its language; all the later singers, and no less from the linguistic point of view, come from him (Reguera's poetic traditions were collected, however, long after his death; for this reason they are also somewhat archaic in the later singers), although naturally On the other hand, they also take elements from the language of their respective terroirs, and frequently also from others with which they are in contact in one way or another, as well as a mixture with Castilian, Bablified or not. But the language of bable literature cannot, in my opinion, be described as a literary language because it has not achieved any unity, from the linguistic point of view, within that little miniature literature that, moreover, like the entire dialect, seems doomed. to a rapid disappearance». In reality, this literature is nothing more than a modality of costumbrista literature from the beginning of the XVIIth century of a markedly comic or burlesque character. In it, through the use of certain expressions of the Asturian language, but also of barbarisms and other archaisms typical of the Castilian vulgar language used in Asturias, the parody of certain characters or situations is reinforced. See in this sense the work of Rodrigo de Reynosa (or Rodrigo de Reinosa) reproduced in the language of germanías, "Colloquium between the Torres-Altas and the ruffian Corta-Viento, in Jácaro dialect" but they can be found in the use of local words from Zamora and Salma in works by authors such as Lope de Rueda, by Juan del Enzina and in other works such as the Coplas by Mingo Revulgo.

Legal status

The Astur-Leonese language only enjoys official recognition in the Portuguese municipality of Miranda de Duero by virtue of the Portuguese Law 7/1999, of January 29, on official recognition of the linguistic rights of the Miranda community, while in the laws In the Spanish organic autonomy laws of Castilla y León and Asturias, the language is only mentioned to generically indicate that it will be subject to "protection, use and promotion", without any binding mechanism being foreseen to carry it out and without any type of officialdom.

The Spanish Constitution recognizes, along with the existence of vehicular languages (those that are recognized as such in the statutes, art. 3.2 CE), the need to protect existing linguistic modalities in the national territory. It is specifically prevented in art. 3.3 of the constitutional text that "the wealth of the different linguistic modalities of Spain is a cultural heritage that will be the object of special respect and protection". In Asturias, given the plurality of the Asturian linguistic reality, the Statute opted for this last modality of protection. Thus in its article 4 it is prevented that "the bable will enjoy protection, its use will be promoted, its dissemination in the media and its teaching, respecting in any case the local variants and the voluntary nature of its learning". In development of these statutory provisions, Law 1/1998, of March 23, on the use and promotion of Bable/Asturian, serves this purpose, promoting its use, its knowledge within the educational system and its dissemination in the media. communication.

Administrative borders are also an obstacle for those who aspire to the normalization and standardization of the language, due to the lack of an institution that regulates the linguistic domain as a whole. This has meant that in Portugal the Anstituto de la Lhéngua Mirandesa has developed a proposal for orthography in tune with the Portuguese one, while the Academy of the Asturian Language has proposed other types of solutions for the study of the language. The worst part corresponds to the administrative territory of Castilla y León where there is no type of regulation or real promotion.

Their degrees of schooling, utilization and protection gradually diverge. In Asturias it is recognized in the official education of the Principality of Asturias. Thus, article 4 of Law 1/1998 provides, "The bable will enjoy protection. Its use, its dissemination in the media and its teaching will be promoted, respecting in any case the local variants and the voluntary nature of its learning». The Asturian subject is included in the study plans as an optional subject, despite its voluntary nature and presents a high level of schooling with almost 80% of students in primary school and more than 30% in secondary school.

In Miranda it has a degree of presence in the schools of Tierra de Miranda, and in León, for its part, it is taught in adult literacy courses in towns in the provinces of León, Zamora and Salamanca, having also established as an extracurricular activity in some educational centers in the city of León in the 2007/2008 academic year.

Geographic distribution

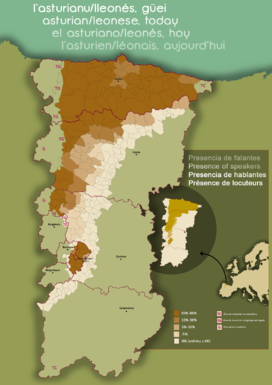

Linguistically, it is considered that within the Astur-Leonese linguistic domain, the denominations known as Leonés, Asturiano or Mirandés form part of a macrolanguage, understood as a language that exists in the form of different linguistic varieties, where the isoglottic traces, especially in Vocalism and cultured groups evolve from West to East, thus sharing some traits with Galician-Portuguese and Spanish.

By geographical extension, linguistics describes that the fundamental features of the Asturian language currently extend through Asturias, León, Zamora and Miranda do Douro. The common character of Astur-Leonese in all these territories is not characterized by being an aggregation of an Asturian dialect, another from Leon, another from Zamora and another from Mirandés; The first scientific division of Asturias-Leonese, described by linguistics, is precisely another, vertical and divided into three cross-border dialect blocks shared mainly between Asturias and León: Occidental, Central and Oriental. Only at a second level of analysis could smaller entities be described. Political or administrative entities and linguistic spaces rarely coincide biunivocally, the most common is that languages cross borders and do not coincide with them.

Number of speakers

There is no study that accurately determines the number of patrimonial speakers of the Astur-Leonese linguistic domain, since no statistical investigations have been carried out in the Leon area. On the other hand, in Asturias and Miranda the data can be considered quite accurate. Therefore, transitional languages such as Lebaniego are not included in this section due to their high level of Spanish.

| Location | Native speakers | Other | % on total Speakers of Asturleon |

| Asturias | 100 000 | 450 000 | 76.3 |

| León and Zamora | 50 000 | 25 000 / 100 000 | 20.8 |

| Braganza District | 15 000 | 2 |

Classification and varieties

In the classification used by Ethnologue, Astur-Leonese is an Iberromance language of the Western Iberian subgroup, just like Galician-Portuguese and Spanish.

Asturleonese varieties

The western dialect of Astur-Leonese is the most extensive geographically, while demographically the central variety is the most widely spoken in quantitative terms.

- Western Bloc: it is the block of greater territorial extension and covers the dialects of the west of Asturias, León, Zamora, and in Portugal the municipality of Miranda de Duero, and the populations of Rio de Onor and Guadramil. Features, facing the central block:

- - Conservation of decreasing diptongos ou and ei (as in caldeiru and cousa).

- - plural females in - (houses, cows), although in San Ciprián de Sanabria there are also female plurals in -.

- - It has three possible solutions in diptongation or brief Latin tonic (door, bid, bid).

- Central block: groups the dialects of the center of Asturias and those of the lioness region of Argüellos. Although its territorial extension is lower, it groups the largest number of speakers, because the Asturian part is the most populated of the entire linguistic domain. Most notable differences regarding the western bloc:

- - Termination in - for plural females (les cases, les vaques).

- - Monoptongation of decreasing diptongos (calderu, Something).

- - Single diptongation or (door).

- Eastern Bloc: it covers the dialects of eastern Asturias and the north-eastern zone of the province of León. One of the main features that differentiates it from the other previous linguistic blocks:

- - La f- Latin initial becomes a h- vacuum.

- - It has two possible solutions in diptongation or brief Latin tonic (door and bid in Cabrales).

Tree of linguistic varieties and regions that it groups together

| Asturleon |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Comparative text

- Cabrales (Asturias oriental).- It was a fríu day and acabin per a llenu d’elu. The veryer and the so hombri arrivein colos ñeños a la ḥuonti las Callras pela ñochi. Intamos llover and garró-yos munchu water and abellugarinse nuna of the huts ḥechas de ḥuoya del Llosu ondi aviarin un ḥuou nel llar and llechi with ñatas.

- Infiesta – L’infiestu (Central Asturies).- And it was a cold day and they're walking for a xelu full walk. The veryer and the so home arrive in colos ñeños to the ḥuente les Callres pela ñuechi. Intamos llover and garró-yos muncho agua y abellugarense nuna de les cabañes feches de ḥueya del Llosu onde aviaren un ḥueu nel llar y llechi con ñates.

- Oviedo – Uviéu (Central Asturies).- And it was a cold day and they're going for a full of xelu. The veryer and the so home arrive in the nen colos to the fonte les Callres peel nueche. Intamos llover and garró-yos muncho agua and abellugarense nuna de les cabañes feches de fueya del Llosu onde aviaren un fueu nel llar y lleche con nates.

- Aller – Yesterday (Central-Central Asturies).- And it was a cold day and they were walking for a.inu walk of xilu. The veryer and the so home yegoren colos nenos a la fonte las.ameras pea nuitse. It entamó yover y garró-yos muntso agua y abe.ugorense nuna de las cabanas fetsas de fueya del.usu onde avioren un fuíu.ar y.etsi con natas.

- Candamo (West Asturias).- Yara a cold day and they were walking for a full of xelu. The veryer already’l sou home arrives a nen colos to the fonti las Calliras pea nuochi. Entamóu llover ya garróu-ys muncha agua ya abellugarunse nuna de las cabanas fechas de fuoya del Llousu onde aviarun un fuou nel llar ya llechi con natas.

- (Western studies) Yara a cold day and they were walking for a full of xelu. The veryar ya’l sou home arriveun colus neñus a la fonti las Calliras pela nuachi. Entamóu llover ya garróu-ys muncha agua ya abellugarunsi nuna di las cabanas dates de fuaya del Llousu ondi aviarun un fuau nel llar ya llechi con natas.

- Luarca –).uarca (Western Asturies).- Yara a cold day and they were wearing a xelu's canvas. The veryer already’l sou home.egaran cones nenos a la fonte las.ameiras pula nueite. Entamóu.over ya garróu-ys muita augua ya abe.ugaranse nuna de las cabanas feitas de fueya del.ousu onde aviaran un fueu nu.ar ya.eite con natas.

- Degaña (Southwest Asturias) and Palacios del Sil (Leon).- Yara a cold day and they were purging a shilling of xelu. The crowd already’l sou home chegonun cones nenos a la fonte las.ameiras pula nueite. Entamóu chover ya garróu-.es muita augua ya abe.ugonunse nuna de las cabanas feitas de fuecha del Chousu onde avion un fueu nu.ar y.eite con natas.

- Cabrera – Cabreira (Leon).- And it was a cold day and they were pur a caminu chenu of xelu. La muyere y el sou home chegorun coñus ñeñus a la fuente las Calliras pur la ñueite. Entamóu chovere y garróu-yis mueita augua y abellugarunse ñuna de las cabins feitas de fueya del Chousu onde aviorun un fueu ñu llare y lleite con ñatas.

- Galende (Zamora).- And it was a cold day and they were pur a gelu cluen. A mullere y el sou home chegonen coñus ñeñus a fuonte as Calliras pur a ñuoite. Entamóu chovere y garróu-les muita augua y abelluganense ñuna das cabins feitas de fuolla del Chousu onde avionen un fuou ñu llare y lleite con ñatas.

- San Ciprián – San Cibrián (Zamora).- And it was a cold day and they're going to pur a gelu chenu caminu. A mullere y el sou home chegonen coñus ñeñus a fuonte es Llamaires pur a ñuoite. Entamóu chovere y garróu-les muita augua y abelluganense ñuna des cabañes feites de fuolla del Chousu onde avionen un fuou ñu llare y lleite con ñates.

- Santa Cruz de Abranes – Santa Cruz d’Abranes (Zamora).- And it was a cold day and they were pur a caminu tsenu of xelu. A mullere y el sou home tsegonun coñus ñeñus a fuonte as Calliras pur a ñuoite. Entamóu tsovere y garróu-lles muita augua y abelluganunse ñuna das cabins feitas de fuolla del Tsousu onde avion un fuou ñu llare y lleite con ñatas.

Transitional speech

The affiliation of the transitional languages to the Astur-Leonese group is disputed by some philologists (who consider them separate languages in their own right or part of the language corresponding to the other linguistic domain with which they make transition):

- Asturias

- Eonaviego or gallego-asturiano, is considered a galaxy-Portuguese variant very influenced by the Asturleonian; it is spoken at the western end of Asturias. As the limit of the Galician is usually defined by the non-diptongation of the brief Latinas /ö/ and /ë/, the eonaviego is attached to the Galician-Portuguese domain (alone. 'soil', jealousy 'blind'). However, the astur-Leonese limit is not usually defined by the diptongation or not of the short vowels (since the Spanish also diptonga) but by the palatalization of the /l-/ initial in /--/, and from this criterion at least half of the eonaviego territory (from the Porcía to the Frexulfe river: crane 'luna', llogo 'after') is ascribed to the Asturleonian linguistic domain.

- Cantabria

- Cántabro o montañes, talks about the transition between Asturleon and Spanish, spoken in Cantabria extreme oriental of Asturias and areas of northern Castile and Leon.

- Southwest of Salamanca

- Talk about The Rebollar

- Extremadura (mainly the north of the province of Cáceres)

- The Extremeño or Altaextremeño, often improperly called the Castúo, was also in this group, since it was considered a transition between the Eastern Leon and the Southern Castilian, it is currently considered a more dialect of the Asturleonian language. Only the High Extrem, since the Mid-Extremeño and the Bajo-Extremeño are at least since the centuryXVII You speak Southern Castilians of transit with the lioness.

- Caceres Province (in or without relation to the previous one, according to authors)

- Fala (Fala Extremadura, of Galician-Portuguese affiliation with asturleon and Castilian influence. Speaking in three villages in the north of Cáceres: San Martín de Trevejo (Sa Martín de Trebelhu), Eljas (As Elhas) and Valverde del Fresno (Valverdi du Fresnu).

Linguistic description

Phonology

Vocalism

- Possibly the most characteristic trait that phonetically defines the asturleonian linguistic domain is the inclination of the closing of the final atonous vowels: lleñi 'wood', nuechi / nueiti 'night', baxu 'low', llechi / lleiti 'leche', and not final: Dear 'here', vicin 'baby', vixigu 'vejigo', ufide 'offens', mulin 'molino', fur 'hormiga', etc. The massive closure that reduces to a/u/i the atonous vocalism occurs throughout the Asturleonian domain and extends with particular strength towards the transition talks with the Spanish: Speaks of El Rebollar in Salamanca (Nochi, ḥoci 'hoz', mesmu, dubri 'doble'), extremeño (ñubi, Grandi, libru, ḥuerti) and clink (lus poblis, lus hombris, I triji, Distimi, I drank you, ḥuenti, mitilu in bulsu, il curdiru). However, and for the asturian case, ALLA has regulated etymological forms: Take it., vecín, molten, costiellaand only responds to the phenomenon in isolated cases: sti 'this'. Esi 'That's right. That one. 'that one' ♫ pumar 'manzano'. ufrir "offreer". firir 'herir' elli fire 'the wound'. midir "measure." vistir 'vestir.' Follow 'follow' ≤1⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2 according to Δ *secundu), Venti 'veinte' θ *viginti (however dolce 'doce' Δ *duoděcim, no **dolci).

- Division in two large blocks of Asturleon (West and Central-Eastern respectively) according to whether or not the old decreasing diptongos /EI/ and /OU/ also present in the galaico-Portuguese group and originated in: 1.- the Latin diptongo *au: maurus boli mouru / moru, 2.- Latin group *al+C: alterum outru, otru, 3.- Latin group *ul+C: pulsum pousu/ posu, 4.- Latin groups *ucc, *upp and *utt: tuccinum Toucín, tocín. However, the decreasing diptongos differ between Galician and Asturleon, as they occur in the latter, cases of realization that do not exist in Galician: cilia asturleonés ceiya, Galician cella 'ceja', concilium asturleonés conceiyu, Galician Concello, meum asturleonés mieu ▪ miou, Galician meu 'mi', ego asturleon yeu ▪ you, Galician eu 'me', eccu-hic asturleon eiqui, Galician here., corium asturleonés Cueiru, Galician coiroetc.

- As in Spanish, Occitan and Aragonese, diptongation of the short Latin tonic vowels / Column/, with three possible results according to dialectal varieties: door. cuervu (general) bid, cuorvu (Western schools, Sanabria, Miranda do Do Douro and Cabrales) and bid, quarvu (Cudillero), and /ě/ with two possible results earth terra, Good. (general) and Bullshit, bian in Cudillero.

- Like in Aragonese (it was. ♫ Folia, güello ¢Ü pueyo Occitan (“podium”),huelha ♫ Folia, uelh and old Mozárabe (uello development of the diptongo /UE~UO/ de /ů/ ante yod: güeyu / guoyu 'ojo' cedesuLu, wasya / fuoya 'hoja' Δ *foia Δ folia, remueyu / remuoyu 'remojo.' restrueyu / restruoyu 'rastrojo', buechu "eight." wasyu 'hoyo' ≤1⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2 puexu 'poyo, podio' ≤ podium, but unlike the Aragonese does not produce the diptongo /ě/: Seya "sea." Espeyu;u(cf. Aragonese spy.).

- Absence of diptongation of the most consonant nasal: fonte 'fuente', Put on. 'puente', dondiu 'duendo, manso' Δ domiYou, ♪ 'luengo,long', bonu 'good', conca 'fall', contu 'count, DRAE-2', None of you sound? 'Don't they ring you?

- Conservation of the diptongo /ie/ ante /-s/ and /-rl/ grouped in voices in which Spanish reduced to simple /i/: watch her. 'Look at him.' feet 'prisco', Right. 'Christra'. viéspera 'vispera' viespa viéspara 'avispa' priesa 'prise'. ciscu 'cisco', or. inc. viesgu 'I live.' Salmantino stock 'arada' ♫ Reverse is asturleonism and could also be Spanish risk,[chuckles]required] as far as the last name is concerned is of Asturian origin.

- Apocope of the final vowel /E/ after nasal /N/: vien 'come', ♪ 'have', Put it on. 'pose'. After liquid /R/ and /L/: salt 'sale', I want it. 'Would', and behind /S/ and /Z/: clis 'eclipse', clas 'class', envás 'Envase', bass 'base', merez 'merece', Inlláz 'Link', diz 'dice', indiz 'indice', héliz 'Hélice', vertex 'vértice', cross 'cruce', conduz 'drive', cuz 'cuece', Cues 'cose'.

- Conservation of the final etymological vowel /E/ of Latin groups -etis, -itis: llide 'lid'. vide 'vid'. vitis. rede 'red'. wall 'pared'. Maybe. 'huésped' headquarters 'sed.' aspide 'spid'. lawn "crowd".

- Reaction against hiatus with the insertion of epentic palatal consonant /y/: ♪, oyiu 'hear', Cayida 'fall', Believe You believe, mayestru, criyáu 'Cryed', ideya 'idea', feud 'faith', puya. piyor 'peor' Δ peioris, o /g/: rigu. ríu Δ rivus, nigu. Niu. nidus, Pu. megollu 'meollo' Δme(d)ullum.

Consonantism

- Conservation F Latin in initial and intervocálica position except in the Asturian-Eastern dialect and talks about transition that maintain an intermediate stage /ḥ/: fíadu~fégadu 'liver. Approach 'ahogar' fema 'beautiful'. skirt 'talk' ♫fabulāri, fi 'higo'.

- Palatal /Y/ results from -LY- and -C'L- Latin, except in the southern dialects of the Mirandes and Sanebris: to 'woman' ≤3 courtya 'corteza' Δ *curticula, although sometimes lention occurs Wow.~fiyu ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü abeya~abea 'abeja'. The same result is given in eonaviego, talks about transition with the Gallego.

- Solutions in prepalatal fonema deaf fricative /š/ (which in Spanish evolved to watch sorda /x/) for different Latin groups -SS-, D + yod/, /x/: coxu 'cojo', xatu 'jato', baxu 'down.' Same result for groups IU, GI, GE xenxiva 'empty' Δ *gingiva, save in asturian-oriental dialect: xugu~Uruguay 'yogo', xuntar~untarring 'Join', xelu~elu Ice.

- Palatalization of the initial simple L- Latina (conserved as such in Spanish and Galician) with different phonetic results. It is palatable in the western regions of Cantabria: Take it. / lleite 'leche', Ilingua 'language', ♪ 'luna', llume 'light' (such as in Aragones and Catalan). Sometimes palatalization occurs even inside word All right. 'alabar.' rellatu ♫ Relatus, ♪ ♪ al'aqráb, callavera (a)varia, allantre I'm ad-ante.

- Palatalization in /LL/ of the R'L group perlla 'perla' PIRuLA Garllar 'garlar' GARRuLARE, burlla 'burla' BURRuLA, Parllar 'parlar' PARoLARE, Carls 'Carlos' CARoLUS, esterllina 'Sterlin'. STERLING, pot 'orla' ORuLA, pot 'borla' BURRuLA, scarllata 'scarlata' θ iškarláṭ, birllar 'birlar', merluza 'merluza'.

- Palatalization in /LL/ group S'L apusllar ¢Ü PUSTuLA, islla; INSULA, Pesllar 'close'. PESTuLARE, used 'hoguera' Δ*uslada USTuLATA.

- Palatalization in /LL/ assimilation product L ≤ miRacuLu ▪ My LacuRu ▪ milla, paRaboLa ▪ paLaboRa ▪ Pallabra, peRicuLu ▪ peLicuRu ▪ pelligru, chaRacteR caretre ▪ street, aRatrum ▪ Ladru ▪ alladru 'Arado', peRegrinum ▪ peLegrín ▪ pellegrín 'peregrino'.

- Palatalization in /LL/ of /L/ as a result of the formation of a diptongo: valentis Valley, calentem Shut up., alecrem ▪ allegre, collobra culuebra. snake., alenitus ▪ allentu, collection ▪ ♪ 'cosecha'.

- In front of the Spanish, and in coincidence with the Galician, the inner group -MB- is preserved without reducing. It continues throughout Cantabria: llamber'lamer', llombu 'lomo', camba 'bed, pin of the car', Damage 'amelga'.

- The secondary group -M'N-, originated by the loss of a Latin atone vowel, was reduced in asturleon to a simple /-m-/ except in the Asturian-Eastern dialect: fame 'hambre'iNe, Semar 'sembrar' Δ semiNare, enxame 'enjambre'.iNe, No. 'Name'iNe, # 'cumbre'iNe, Llegume 'legumbre'.iNe, Esllumáu 'dispainted'inatus.

- Asymilation of /-R/ end of the infinitive against encyclical pronoun: quiet 'heat it', xubillu 'look it', Morrenos 'to die', I 'contarles', da-yla 'Give it'.

- In front of Spanish, conservation of the Latin group -N'R-: Tienru. TENeRU 'land', xenru. GENeRU 'Yesterday', vienres. VENERIS 'Friday', senra. SENIRA 'Serna', Censorship. inCINeRATA 'Czeiza', He's got it.. TENIRA 'will'. etenru aeternus 'eterno' and pienres 'pies' (in the phrase vienres party ente les pienres) are cases of hypercorruption.

- Conversion in /L/ of the first element of Latin groups -P'T- / -P'D-: xaldu 'jaudo, soso.'idus, selmana 'Semana'iMana, estreldu ▪iyour 'striking', trelda ▪ida 'barro'. -B'T- /-B'D-: dulda ¢Üita 'duda', recaldu "required" coldu Cubito 'codo'. -V'T- lleldu LEViyour 'leudo'. -D'B-: vilba ”uba 'viuda'. -D'C-, T'C: xulgar IUDicare 'juzgar', dolce ”ecim 'doce', thirteen ¢Üecim 'trece', selce.ecim 'diecise', Major. ▪iHow 'majority', skin 'pega, obstacle'iCa, Pealgu ► pediatiCu 'peaje'. -P'S- And the ≤ gypsu 'yeso'. -F'D-: trelda ► trifida 'trébol'. In this sense, it is considered that terms as buttocks;ior belfo ¢Ü ¢Üidus are asturleon loans to Castilian, as in this language you could expect *naga And...Befo. Also Portuguese Julgar is considered loan of the Asturleon.

- Tendency to the epentesis of oclusiva cum liquid: Gurupu 'group', taragumiar 'Bring', taranca 'trace', Toronchu 'troncho', barenga 'brenca', Berezu, bereciu 'brezo', garayu 'grajo', tarozu 'trozo', tarabiella 'trabilla', Calaviya 'slave', garanu 'grano', curume / crume 'cumbre'. Possibly it is a phenomenon of substrate that coincides with the Basque language (cf. granum /2005 Garau 'grano', Clunia *Culunia *Curunia Coruña del Conde).

Morphosyntax

Morphology

- The centre-oriental asturleone retains a third unique adjective mark to accompany the incontable realities known as "neuter of matter" that is made in /-o/. In this way the adjectives present three terminations -u, -a, -o, as they should accompany a male noun, a female or a neutral (or uncountable) respectively: mozu guapU " handsome boy," moza guapA 'Pretty girl', . 'Pretty people'. Other examples meat No...meat tienra or mofu llandio 'soft muscle' notmofu llandiu.

- As in Aragonese, differentiation between the DES- prefixes (from Latin dis-) and ES- (from Latin ex-). The first marks the opposite action facer 'doing'/desfacer 'undo', ♪ 'mezclar'/dislike 'separate'. The second indicates action, Esgayar 'deceat', I'll be right there. 'down'.

- Quite often, and without etymological justification, the appearance of vowel /i/ or “epenthetical yod”: blandiu / llandiu 'blando', mundiu 'world', muria 'muro', llastria 'lastra', Fuercia 'force', rondiu 'redondo', rutiu 'eructo', mostiu 'let', curtiu 'cut'.

- Insecure of the final tuning liquid (/R/ and /L/) that is reinforced with insertion of -e paragogic: trébole 'trébol', treee 'tree', jail, zúcare 'sugar', almíbare 'almibar', ambare 'Ambar', marblee, fréxole 'fréjol', which sometimes develops secondary syncopa: Zucre, deble, fever, alcazre 'alcázar'. In the extreme this insecurity is solved with the fall: carci 'carcel', arbu 'tree', trebu 'trébol'.

- Insecurity of the final atone/-N/ nasal that disappears or reinforces with insertion of -e paragox: Dentame/dentámene 'denture', virxe/virxene 'virgen', xerme/xérmene 'germen', vierbe/viérbene 'gusano', Quexume/I'm sorry. 'burning', moblame 'mobiliario'.

- Insertion of atonic suffixes – ALU, -ARU, -ANU without etymological explanation or semantic modification: ñicu / ñícaru 'girl', viespa / viéspara 'avispa', shell / Conchara, Ilasca / lláscara 'lasca', llueca / ## 'cencerro', xuncu / xuncalu 'junc', Zuecu / Zuécalu 'zueco', carambu / carámbanu 'carámbano', Was. / Scana 'socavón', demongu / demonganu / demongaru 'demon', tambu / Tombanu 'tapadera', ciegu / cégaruetc. Sometimes it develops in secondary syncopy: viespra, xunclu,nucla ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ñocla ≤1⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄2⁄ Take it. 'lepra', Congaru 'congrid', Chigare 'chiger, cider tavern', Nobaru ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü ¢Ü búgare 'bogavante' bugre ≤2. Spanish carambano *kar-ambo is considered asturleonism. Possibly it is a substrate phenomenon of a language that tended to the proparoxytone accent, cfr. the Galician solutions with suffix ego/a: cobra / Copper, Cuncha / Conchega, hates / odega, Look. / skin, Salamanca / Salamantigaetc.

Syntax

- Article insertion before possessive: mio/miou mariu 'my husband', to/tou xatu 'your calf', les nueses costumes 'our customs', the so/sua cabanna.

- Possibility of postponing the possessive to the noun followed by the DE particle: of mine/miou 'my husband', the xente de nueso 'our people', les vaques de so/sou 'Your cows'.

- As it happens in Italian, adverbial function of the neutral adjective - or, where Spanish, except exceptional cases (Speak louder, run fast, plays dirty.), has solved with the modal suffix -: I don't know who to facer made me curious? 'Are you not able to do something carefully / with care?', serious 'Speak seriously, seriously,' Watch out 'He did it carefully, with attention', Dixome tienro 'He said tenderly to me, tenderly.' Thus, opposition occurs skirt asturianu 'Speak asturian, asturian language' in front of Asturian skirt 'Speaks asturianly, in the Asturian way.'

- Genitivo in aposition or unmarked. In all languages romances the function of genitivo is marked by preposition of, in asturleones instead this brand is completely missing and the function must be deduced by the context: car Xuan 'John's car, the fía'l rei 'the daughter of the king', Oxenu 'The Garden of Eugenio', ca'l 'house of the priest', the meu'l puoblu 'in the middle of town'. It is the same situation as in old French that allowed constructions of the type la fille le rei 'the daughter of the king', the gent le rei Hugon 'the people of King Hugo'. Closely related is the use of prepositional syntagmas without connector of as it occurs in Catalan and ancient Castilian: apron the cough güeyos 'in front of your eyes', front l'ilesia 'in front of the church' (cf. Catalan enfront l'església).

- Postverbal situation of direct and indirect supplements, except in negations and after the relative that: Vendi-y-lo 'see him,' told me 'He told me,' dexé-y 'I left him,' dexélu 'I left it', val-lo 'it's worth it.' daben-y-les 'they gave them.' But, Nun told me 'didn't tell me,' nun-y dexé 'I didn't leave him,' nun the waltz. 'no good', nun-and daben 'Don't let them down', You have to face it 'You have to do it', You have to miss me. 'You have to talk to me.'

- Opposition of the prepositions PER 'time-space' θ *per and BY 'cause-effect' Δ *pro: subi staircase 'Go up the stairs' / subi pola staircase 'Go up the stairs.' In all Romany only asturleonian and French (pair ♫ pour the old Latin distinction remains.

- Verbal peripherals finish + infinitive, duty + infinitive, dir + infinitive, having + infinitive, lack the prepositions DE, QUE and A: Just call. They just called you, Must be the two of you. 'must be both,' the sabadu must come 'They were coming on Saturday', you quit smoking 'I'll quit smoking', You have dexed the keys 'You have to leave me the keys.

- New Americanity of the past participle in gender and number with the direct object in the formation of the perfect preterite composed: them songs that Lluisa tien cantaes 'the songs Luisa has sung.' It is an arcaism that met the medieval Spanish (the songs Luisa has sung) and also preserved in French: the chansons that Louise blackmailed.

- Remains of the old perfect of the moving verbs built with the auxiliary being: The times are coming from... 'The time has come for...' They're coming from... 'have come from'. It is again an archaism that met medieval Spanish and also preserved French: sont arrivées 'have arrived', and the Italian Sono arrivate 'Have arrived.

- The conjugate use of the subjunctive is avoided by means of the infinitive: with no face 'Let's do it.' I went without them to notice nothing 'I left without them reading anything.' Before Xuan Spertar 'Before John wakes up,' Three sunshine 'After the sun sets,' nun tien who-and face it 'no one has to do it to her,' You eat 'to eat', I could eat my dad. 'My father broke his back so I could eat', He sent them to sew. 'He kept them sewing' in front of He sent them. 'it kept them sewing'.

- The conjugated use of the subjunctive is avoided through the periphrasis in + gerundio: Let me know when it's time 'when it's time you tell me,' in xintando marcho 'when I eat,' Seeing Iyán, call me When you see Julian, you call me, finishing + Infinitive: Xintar withered 'as soon as I eat,' just to see Iyan call me 'as soon as you see Julian you call me.'

- In asturleones there are no compound verbs with There must be and it is never said: ♪ he isu, ♪ there was falau. Therefore the simple perfect preterito of indicative is always used regardless of whether the action is within or outside of a temporary space: the conseyeru faló(u) güei and the ministru faló(u) yesterdayi 'the counselor has spoken today and the minister spoke yesterday.' falasti yesterdayi and falasti güei 'You spoke yesterday and you talked today.' However, as in Portuguese and Galician the past action within an unfinished time space can also be expressed through the preterito pluscuamperfecto the conseyeru falare güei and the ministru faló(u) yesterdayi 'the counselor has spoken today and the minister spoke yesterday', already ate. 'I had already eaten here,' I will finish singing(e) when I(u) arrived(i) 'I was done singing when I got here.'

- The imperative is made in -a / ai in the first conjugation; skirt 'talk', fali 'talk', in -i, in the second: llambi 'lame', Callbéi 'lamed' and -i, -i in the third: xubi 'sube', xubíi Get up.

Comparison tables

| Mozárabe | Galaicoportugués | Asturleon | Castellano | Navarroaragones | Catalan | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Consonants | ||||||

| F- | f | f | f h ~ (dialectal) | h ~ ▪ Ø f | f | f |

| PL-CL- | pl kl | t implied | t implied / MIN | pʎ / pl kʎ / kl | pl kl | |

| FL- | fl | t implied | t implied / MIN | / fl | fʎ / fl | fl |

| L- | j / | l | l | / l | ||

| N- | n | n | n / | n | n | n |

| -L- | l | Ø | l | l | l | l |

| -N- | n | Ø | n | n | n | n |

| -LL- | l | / | ||||

| -NN- | n | |||||

| -LY- | j | / | ♫ ▪ x | |||

| -NY- | ||||||

| Ce,i- | t implied / d | ts ▪ s (θ in Galician) | ts ▪ θ | ts ▪ s ▪ s ~ θ | ts ▪ θ | ts ▪ s |

| - Ce,i- | t implied / d | ts ▪ s (θ in Galician) | ts ▪ θ | ts ▪ s ▪ s ~ θ | ts ▪ θ | ts ▪ s ð ▪ Ø (coda) |

| Ge,i- | j / ♫ | ♫ (MIN in Galician) | MIN (♫ in mirandés) | Ø / /x | ♫ ▪ t implied | ♫ |

| - CSC.e,i- | MIN | MIN | MIN | MIN ▪ x | MIN | MIN |

| -CS- | MIN | MIN | MIN | MIN ▪ x | MIN | MIN |

| -CT- | ht | jt | jt t implied ~ ts (dialectal) | t implied | jt | jt |

| -(U)LT- | jt | jt | jt (n)t (dialectal) | t implied | jt | lt |

| -P-T- -C- | p t k / b d g | b d g | b d g | b d g | p t k / b d g | b d g p t k (coda) |

| -MB- | mb | mb | mb | m | m | m |

| -ND- | nd | nd | nd | nd | n | n |

| -M'N- | mn | m | mn / m | mbr | mbn / mbr | m / mbr |

| Vocals | ||||||

| AL + Cons. | aw | ow | ow | o/o | o/o | ► / Al |

| AW | aw | ow | ow | or | or | |

| AY | aj/ej | ej | ej | e | e | e |

| ‐ | ji | E | ji | E | já/j | I |

| Y+ And | wé | or | wó / wé/ wá | or | wa/wé | ú/í |

| ‐ | jé/e | ‐ | ji | ji | já/j | E |

| ́ | wé / o | ́ | wó / wé/ wá | wé | wá/wé | ́ |

| E | E | E | E | E | E | ‐ / E / ► |

| or | or | or | or | or | or | or |

| -O# | o / e / Ø | o/o | o/o | or | o/ Ø | Ø |

| -E# | e/o / Ø | e / i / Ø | e / i / Ø | e/ Ø | e / i / Ø | Ø |

| -AS# | as / is | ʃ・ (a in Galician) | as/ That's it. | a | a | ► / That's it. |

| Galaicoportugués | Asturleon | Castellano | Navarroaragones | Catalan | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n/n) nh | (n/n) nn | (n/n) nn | (n/n) gn/ng nig / ing inn / ynnn / ny | (n/n) yn / ny | |

| (li/l) lh | (li/l) ll/y | (li/l) ll | (li/l) gl / lg / lig yl / il / yll | (li/l) l/l | |

| j | li lh | li ll / and | li i/j/g | li gl / lg / lig yl / il / yll | li il / yl |

| - - - - - | g/i/j | g/i/j | gg g / j / i | jh/i/g | g/i/j |

| MIN | x | x | x / ss | sc / isc / ss sç / yss / is | ss / iss |

| x / ix / g | g/ x / ch | gg ch'' | sc / çc g/i | tx |

| Latin | Gallego | Asturleon | Castellano |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diptongation and . | |||

| P)RTA(M) | carrier | door | door |

| )CULU(M) | ollo | güeyu güechu | eye |

| TIFMPU(M) | Tempo | tiempu | time |

| TIFRRA(M) | terra | earth | earth |

| F- (initial position) | |||

| FAC giftRE | facer | facer facere | make |

| FgivingRRU(M) | ferro | fierru | iron |

| L- (initial position) | |||

| LÀRE(M) | Lar | ♪ ar | Lar |

| LVELPU(M) | . | ♪ obu | . |

| N- (initial position) | |||

| NATIVIT ATE(M) | Nothing. | ñavidá | Christmas |

| Palatalization of PL-, CL-, FL- | |||

| UNPA (M) | chan | chanu llanu | llano |

| CLAVE(M) | chave | chave Key | Key |

| FLUEMMA(M) | chama | chama flame | flame |

| Decreasing diptongos | |||

| CAUSA(M) | cousa | cousa Something | Something |

| FERRAR)U(M) | Ferreiro | ferreiru ferreru | blacksmith |

| Palatalization of -CT- and -LT- | |||

| FUE(M) | fetus | feitu fechu | fact |

| N)CTE(M) | noite | nueite nueche | night |

| M/25070/LTU(M) | Moito | mueitu ♪ | a lot. |

| AUSCULT | Scot | escueitare scueichare | listen |

| Group -M'N- | |||

| H)M(I)NE(M) | home | home | man |

| (I)NE(M) | fame | fame | hunger |

| LvolvM(I)NE(M) | lume | llume ume | Light |

| -L- intervocálica | |||

| GGN(M) | Xeo | xelu | Ice |

| FILICTU(M) | fieito | feleitu feleichu | Done. |

| -l- | |||

| CAST sumaLLU(M) | castelo | castiel castieuu | castle |

| -N- intervocálica | |||

| RANGNA(M) | ra | frog | frog |

| Group -LY- | |||

| MUL)ERE(M) | muller | to ♪ | woman |

| Groups -C'L-, -T'L-, G'L- | |||

| NOVACANCELA(M) | Navy | ñavaya | Navaja |

| VETANCELU(M) | hair | vieyu viechu | Old man |

| TEGANCELA(M) | Tella | teya | Teja |

| Mirandés (West Asturleon) | Senabrés (West Asturleon) | Resto of dialects (West Asturleon) | Central Asturleon | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic elements | ||||

| Diptongos (1) | -I-I-I- | -I-I-I- | -I-I-I- | -I'm- |

| Diptongos (2) | -I'm- | -I'm- | -I'm- | -I'm- |

| - Or, | - | - | - | - or; |

| -As, | -as, | -as, | -as, | - it's, in. |

| E-, I-; O-, U- | ei-; ou- | e-, i-; o-, u- | e-, i-; o-, u- | e-, i-; o-, u- |

| L- | Ihado, lhobo | Ice cream, weep | llau /,au, /obu | llau, llobu |

| S- | ||||

| PL-, FL-, etc. | shama, chober | shama, huvere | shama /,ama, chover / overover | flame, rain |

| Sibilante | /s/, /z/, /,/, ///, /х/, / | /s/, /θ/, / implied/ ([χ]) | /s/, /θ/, / a/ | /s/, /θ/, / a/ |

| -D- | tired | (d)o | Cansáu | Cansáu |

| -LL- | ♪ | Horse | caballu / cabauu | ♪ |

| -NN- | anho | year | añu / anu | luu |

| - LJ- | abeilha | abella | abeya, abeya, abecha | abeya |

| Morphological elements | ||||

| Art. Def. | l, la, ls, las | he, a, os, a | el, la, los, las | el, la, los, les |

| Art. Indef. | a, ignoble, uns, ̄ | a, nail, uños, nails | one, one, a few, a | one, one, a few, a |

| Positive ♪ | miu, mie; tou, tue; sou, sue; nuosso; Buosso | mieu, mine; tou, you; sou, súa; nub; Yummy. | mieu, mine; tou, you; sou, súa; nub; Yummy. | my, to, so, nuesu; vuesu |

| Demonstrative | These, you, aqueilhes | these, those, those | these, those, those / | these, those, those |

| Neutral gender | (-) | (-) | (-) | (+) |

| Inf. conjugado | (+) | (-) | (-) | (-) |

| Fem. -AGE | (+) | (-) | (-) | (-) |

Personal pronouns of subject (tonic forms) Mirandés Leon Asturiano

WesternAsturiano

CentralAsturiano

EastCantabrian

WesternCantabrian

EastExtreme. GLOSA Singular 1.a pers. you you you Me. Me. Me. Me. Me. 'me' 2.a pers. You You You You You You You You 'you' 3.a pers. masc. the the Him. Heli Heli Him. Him. Him. 'he' neu. - - - that that that the - 'ello'

(uncountable)fem. eilha eilla eiaa She She She She She 'la' Plural 1.a pers. No nosoutros No No No us. musotrus muhotruh "we" 2.a pers. Bodies Vosoutros Go Go Go You vusotrus vuhotruh 'vosotros' 3.a pers. masc. eilhes eillos ♪ They They They ellus elluh 'they' fem. eilhas eillas eiasas Elles elles/as them. them. Ellah 'las'

Form for adjectives Mirandés Leon Asturiano

WesternAsturiano

CentralAsturiano

EastCantabrian

WesternCantabrian

EastExtreme. GLOSA Singular masc. buonu Good. Good. bonu Good. güenu güinu güenu 'good.' neu. Buono Good. Good. Bonus güeno güenu 'good.' fem. Buona Good. Good. # Good. güena güena güena "good." Plural masc. Boots Good. Good. bonds Good. Bless us. güenus güenus 'good.' fem. buonas Good. Good. bones Good güenas güenas güenas 'good.'

| Location | Linguistic block | Text | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Asturleon dialects | |||

| Talk about Carreño | Asturias | Central Asturleon | Tolos homes are born llibres and pareyos in dignidá and drains, and aviaos that are of reason and conscience, have carried some other pa colos. |

Speak of Somiedo | Asturias | Western Asturleon | Tolos homes are born.ibres already pairs in dignidá already drains already, already aviates that are of reason already consciousness, have been carried out some out cones. |

Pa Pauezu | León | Western Asturleon | Todolos human beings are born.ibres already pareyos in dignidá already dreitos ya, dotaos cumo tan de razón yaciencia, han portase sios outros. |

Cabreirés | León | Western Asturleon | Todolos homes ñacen llibres y pareyos en dignidá y dreitos y, dotaos cumo están de razón y concéncia, han portase hermanibles los unos pa cu cus outros. |

Mirandés | Trás-os-Montes (Portugal) | Western Asturleon | All houman beings naze bleeds and eiguales an denidade i an dreitos. Custuituídos de rezon i de cuncéncia, dében portar-se uns culs outros an sprito de armandade. |

Extreme. | Extremadura / Salamanca | East Asturleon | Tolos hombris nacin libris i egualis en digniá i derechus i, comu spend reason i concéncia, ebin behavel-se comu hermanus el unus conos otrus. |

Cantabri / Mountaineering | Cantabria | East Asturleon | Tolos serishuman nacin libris y eguales en dignidá y drechos and, dotaos comu are of reason and conscience, tién de behavese comu sis los unos conos otros. |

| Other Romance languages | |||

| Portuguese | Portugal | Portuguese | All human beings nascem livres e iguais em dignitye e em direitos. Donated by razão e de consciência, devem agir uns para com os outros em espírito de fraterne. |

| Gallego | Galicia | Gallego | All of you human beings are born free and iguais in dignity and dereitos and, endowed as they are of reason and conscience, they should behave fraternally a cos outros. |

| Spanish or Spanish | Spain | Spanish or Spanish | All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights and, endowed with reason and conscience, they must behave fraternally with each other. |

| Catalan/Valenciano | Catalonia/Valencia/Baleares | Catalan/Valenciano | Tots els éssers humans naixen lliures i equals in dignitat i drets i, dotats com son de raó i consciència, must behave-se fraternalment els uns amb els altres. |

Contenido relacionado

Gallo-Italic languages

Lusitanian language

Phrygian language