Asturian (Asturleonese from Asturias)

The Asturian (autoglottonym: asturianu), also called bable, is the gluttony that the Asturian language receives in the Principality of Asturias, a language that has continuity with the traditional languages of the Kingdom of León in León and Zamora (where it is called Leonese), and Miranda de Duero in Portugal, where it is official by virtue of Law no. 7/99, of January 29 of 1999 of the Portuguese Republic (Mirandés). The very diverse dialects of Asturian are usually classified into three large geographical areas: western, central, and eastern; the three areas have continuity with the Leonese dialects to the south. In the Asturian case, for historical and demographic reasons, the linguistic standard is based on central Astur-Leones. Asturian has a grammar, a dictionary of the Asturian language, (the Diccionariu de la Llingua Asturiana), and spelling rules. It is regulated by the Academy of the Asturian Language, and although it does not enjoy of an official nature in the Statute of Autonomy, a law regulates its use in Asturias.

Some sources, such as Ethnologue, use the term "Asturian" as a synonym for "Astur-Leonese", since in reality all these gluttony names (Mirandés, Leonés and Asturiano) refer to the same language, Astur-Leonese, whose internal division does not only it does not coincide, but it is transversal to the current provincial borders.

Gluttony

Given the little social and political acceptance of calling the language Leonese in Asturias, and Asturian the language in other parts of the domain such as León or Zamora, today a significant number of authors and specialists prefer to refer to the whole as Astur-Leonese, although others continue to use regional or regional denominations (such as Asturian, Leonese, Mirandés, etc.).

Social and cultural aspects

Asturleonese and Asturian

Sometimes mention is made in scientific studies referring to this language with the name of "Asturleones" or "Leonés", especially after the publication of El Dialecto Leonés (1906) by Menéndez Pidal, who considers Leonese or Astur-Leonés, along with Castilian in its different forms. varieties, to Mozarabic and Navarro-Aragonese one of the four dialect groups within the Iberian Peninsula that contribute to the formation of the modern Spanish language. Today most linguists treat Astur-Leonese and Aragonese as independent Romance languages of the Spanish. Menéndez Pidal's terminology was also used in part by his disciples. The reason for this denomination lies in the fact that Ramón Menéndez Pidal prioritizes the sociopolitical aspect, and particularly the fact of repopulation, as a determining factor when it comes to understanding the process of linguistic cohesion in the Peninsula. However, and taking into account that the territory of the former Kingdom of León and that of use of the "Leonese romance" they did not coincide exactly, and that the process of linguistic cohesion was very intense in the south of the domain and earlier than in the north, it must be understood that it is in Asturias where the differentiating features of the language were maintained with greater vitality and firmness. Therefore, it is advocated that the most appropriate term to refer to the current situation in the administrative territory of the Principality of Asturias is "Asturian", while "Asturleonés" to allude to the language in its current and historical global extension.

Name: Asturian or Bable

Both denominations are accepted. In Asturias, bable or asturiano are synonymous terms that refer to autochthonous romance. In 1794, it already appears in the Memorias Históricas del Principado de Asturias by Carlos González de Posada, a native of Carreño, which, up to now, can be considered the first verification of this term ( bable) when referring to the “Asturian language that they say Vable there”. Subsequently, bable has been used more or less frequently, although it is true that it should never have had much popular roots, since the Asturians have mostly called their speech as "asturiano" or "asturianu". This is stated, for example, in the first volume of the Linguistic Atlas of the Iberian Peninsula, published in 1962, where the data collected in oral surveys carried out before the Spanish Civil War are collected, and where question regarding the name of the local speech, the answer was systematically "asturianu" and not "bable".

The same must be maintained in more recent times, according to the socio-linguistic survey carried out by Llera Ramo in 1991. The survey by Llera Ramo, professor of political science and professor at the University of the Basque Country, was commissioned under the mandate of Pedro de Silva, but it was never published by the government headed by his successor, the socialist Juan Luis Rodríguez-Vigil Rubio, although its data was released by some media. Under the mandate of President Antonio Trevín, the Ministry of Culture published the results of the survey in the summer of 1994.

In 1988, during the government of Pedro de Silva, it was decided to develop Article 4 of the Statute of Autonomy of Asturias to regulate the use of the language.

The Law for the Promotion and Use of Asturian includes both terms although, from the Administration itself, the term considered correct is "Asturian" and this is reflected in all the institutions and ministries of the Principality.

Origin and evolution of the language

Asturian originates from the Latin-derived Romance language spoken in the medieval kingdoms of Asturias and León. From Latin written in the 10th and 11th centuries, greatly altered by the local Romance language, there is a very important documentary collection from the Leonese monasteries of Sahagún, Otero de las Dueñas and the Cathedral of León, but of very diverse origin (see document of King Silo). From the examination of the hesitations contained in these documents, it has been possible to reconstruct some of the characteristics of the primitive language spoken in the Kingdom of León, but without having a proper documentary body in the Romance language.

Among these documents, one of the most relevant due to the lack of dependence on the formal requirements of notarial documents, is the one granted in the town of Rozuela (León) and known as Kesos News, which has been dated to around the year 980. As pointed out by the professor of medieval Latin at the University of León, Maurilio Pérez, one cannot speak of dialectal distinctions before the 12th century. "Everything is born from local situations that will later give rise to two dialects", and he adds that the rest is generated little by little due to phonetic and syntactic issues. "It is not Leonese or Castilian, but it can be said that it is one of the documents that has the most romance voices".

Tracking the evolution of the language is lost, however, from the 12th century. At the beginning of that century, a very important strengthening of Latin was observed in notarial diplomas. This trend is evident, especially in Asturias, due to the work of Bishop Pelayo (1101?-1153) and the copyists' office created around him, who will seek a recovery of autochthonous Hispanic forms, against the new trends that come from Europe, observing an absolute distance between the spoken and written language that makes any attempt at reconstruction impossible. A separate case is that of the privilege granted to the city of Avilés, known as Fuero de Avilés, which has been dated the year 1055 and in which a previous jurisdiction conferred by Alfonso VI to the town of Aviles is confirmed. This privilege was studied by Rafael Lapesa in his well-known study Asturiano y Provenzal en el Fuero de Avilés,, and presents, according to said author, an amalgamation of linguistic characters of very diverse origin. In particular, the existence of exclusive features of the Provencal language is verified, which would be explained by the benefits conferred in the jurisdiction itself to the Frankish knights to settle in the town; however, there are few —if not non-existent— the characters that can be linked to the Asturian language. Lapesa specifically points out that not all of them are foreign words and points out four characteristics that would make Western Asturian common, namely: the maintenance of the initial -g- or -j- with sound x, the decreasing diphthongs -ei- and -ou-, the use of the pronoun "per" and the indefinite pronouns 'un', 'none'. All these characters could have another explanation given the importance of the express qualification that is made for Frankish and Galician knights to reside in the town and are not, in any case, exclusive to western Asturian. As Amaya Valencia points out, the The document presents characters present in the Northwest of the peninsula, but as regards the peculiarities of Asturias or especially Asturias, the problem is quite complex to determine.

Apart from this case, which due to its special characteristics deserves a particular treatment, the fact is that it will only be from the XIII century, with the translation of the Liber Iudiciorum (Fuero Juzgo in its romanced version) by the royal chancelleries located in the center of the peninsula, when the Romance language became natural in the medieval diplomatic language.

However, the distancing of the Asturian region from the centers of power located from the XIII century in the center (Toledo) and south of the peninsula (Seville and Córdoba) determined that the Asturian language is absent from the large cartularies of San Vicente, San Pelayo and the Cathedral. However, some reminiscences of it can be found in other medieval cartularies from monasteries further away, such as those of Lapedo in Belmonte de Miranda and San Bartolomé de Nava. An example of the character of the language of that time is found in the following dated 1233 cited by Rafael Lapesa:

In nomine dominj amen. Hio (I) Johan Thomas seeing you conviento de Belmonte lumnadamiente a la Caridat, all of mine heredat quanta yo hey en essa villa que laman ambos mestas, nomnadamiente la quarta dela, por todos sos términos antigos, τ con la mi ration todo la covas de la Vega, nomnadamiente de la vega. Seeing you conviento suso decho all these nomnadas heredades, quanto me en ellos ey o aver owe for numnado price 50 morabedis of real currency τ daquesti price soe me well paid, nenguna thing non remanezco. And therefore these heredades that you Johan Tomas you convient of his ointment of sluggish seeing, des (h)oy in the day, of my iur will be carried away τ in your might be given ye outorgadas by iamais, τ fagades delas all vestra veluntat. Ye if dalguno contra esti mio feyto quier come so bien de mia progenia como destraña, seia damn ya, escomungado del regno de Dios alongado, with Datan τ Abiron que sorbeo la tierra vivo con Simón mago τ con Juda el bringer que ver a nuestra Señor con todas aquestos padesca las dolores del infierono τ peyte a voRafael Lapesa Melgar, The Western Asturian Dialect in the Middle AgesUniversity of Seville, 1998, p. 101.

As an example of the speech of Eastern Asturias, it is worth mentioning the following text from the year 1255 from the Convent of San Bartolomé de Nava cited by Isabel Torrente Fernández of great interest due to the mixture of Latin and Romance terms:

In nomine domini amen. Equum et rationabile est ut ea quae conveninunt ne oblisviscantur litteris mandentur. Ea propter ego the Abbey of San Bartolomé de Nava priora and convent of that same place facemos agreement with you Luis González cura de San Andrés de Cuenya del Concello de Nava, Diócesis de Oviedo in this sort that you serve us of chaplain on Sundays and festivities of the whole year from above and that sacramentedes to us Between Anbas the parties agreed.Torrente Fernández, Isabel: The domains of the Monastery of San Bartolomé de Nava, 13th to 16th centuries, p. 213

According to Menéndez Pidal, the testimonies of the medieval Asturian language are scarce and partial, literary texts and notarial diplomas do not agree in their testimony; neither those nor these reflect with sufficient fidelity the dialect 'leones' (Asturleonese) spoken; and in literary texts, especially, two influences can be seen fighting, literary too, and completely opposite, the Galician-Portuguese and the Castilian, which were not exercised in the same way, much less in the spoken language. The spoken language maintained until today its own characters well harmonized with each other, in which the gradual transition in space is observed, from the Galician-Portuguese features to the Castilian ones; Instead of this gradual transition, the written texts show us an antagonistic mixture, since Leonese (Asturleonese) literature, lacking in personality, moved hesitantly between the two centers of attention that indisputably surpassed it.

From the 14th century, the texts kept an absolute uniformity with respect to the Castilian documents contained in the cartularies themselves.

More recent philologists such as Roberto González-Quevedo, on the contrary, highlight the literary continuity of Asturian since the Middle Ages: Asturian, like other Romance languages, has been used since the Middle Ages in charters, testaments, documents, such as it is easily verified in the Jurisdiction of Avilés, Jurisdiction of Campomanes, etc. Literature in Asturian is, certainly, less abundant and of less quality than one would like, but it is much better and extensive than is commonly believed. Due to their absolute marginalization in official education, there are many Asturians who are unaware that there is even a literature in their vernacular. In rural areas it is still easy to hear from Bable-speakers that their language "cannot be written".

In the XVII century lives the poet who usually starts all the anthologies of poetry in the Asturian language: Antonio González Reguera (Antón de Marirreguera), a priest with a happy life, reminiscent of that of the celebrated archpriest of Hita. He was the one who was the winner of a poetry contest organized on the occasion of the transfer from Mérida to Oviedo of the remains of Santa Olaya, in 1639. In the contest there were poems in Latin, Greek and Spanish. The fact that the winner was en bable says a lot about the presence and acceptance that literature in the Asturian language had at that time. During the 18th century, literature in Bable gained great momentum when a group of important poets appeared in its second half; as well as the impulse that men like Melchor Gaspar de Jovellanos wanted to give to Asturian culture. It should not be forgotten that Jovellanos was in favor of the creation of an academy that would normalize the bable.

The normative Asturian

Together with the three existing dialects of the Asturian language, today a normative Asturian has been consolidated in Asturias which has been institutionalized through the publication of uniform grammatical norms by the Academy of the Asturian Language. This normative standard It is based on the central dialect of Astur-Leonese and finds its roots in the costumbrista literature of the late 17th century, particularly that of the parish priest of Carreño, Antonio González Reguera and other later authors, whose literary work was disseminated by scholars such as Caveda and Nava in XIX century. It should be remembered that this literature arose precisely in the so-called "dark centuries" of other peninsular languages, such as Catalan or Galician, and its appearance at this time can be explained in a context of markedly burlesque literature, characterized by the use of these resources. stylistic characteristic of the then called rustic speech, which equally included the numerous dialects of Castilian that existed in Castile and any peninsular language that was not Castilian. In it, through the use of the Asturian language, but also barbarisms of the Castilian vulgar language, the parody of certain characters or situations is reinforced, but they can be found in the use of local speech from Zamora and Salamanca in works by authors such as Lope de Rueda, by Juan del Enzina and in other works such as the Coplas de Mingo Revulgo. For the rest, the normative Asturian is based on the central dialect of Astur-Leonese, although the normative includes spelling rules for writing in the western and eastern dialects. The appearance of the phoneme -l- in the postnuclear margin of the syllable (yelsu, coldu, lleldu, dulda, etc.) is a characteristic that would be a later evolution than the oldest Asturian historical texts, as Caveda y Nava points out: «The pronunciation of -u- instead of -b- is confirmed by the old words cabdal, cabdiello, dubda, etc. in which the 'u' was substituted for the 'b' as caudillo, caudillo, doubt etc”. Don José Caveda continues saying, «towards the mountains of Teberga it is still said 'coudicia', 'toudo', etc, decreasing diphthongs that in times of safety were undoubtedly in use as was done in see in couplet 35 of Alejandro's poem where it is said "ousar" for 'use' and in couplet 2398 in which it is said "Outumno" for 'Autumn'", Along with these characteristics there are others unknown in medieval texts, such as the formation of plurals or the neuter of matter. Regarding the neuter of matter, see Viejo Fernández (1993) who analyzes the documentation of the medieval Asturian language of the monastery of Nava from the 13th and 14th centuries, in a document from 1374 its use is already verified ("una fanyega de escanda linpio e pisado») (Old Fernández, X. (1993): «La llingua de los documentos del monesteriu de San Bartolomé de Nava (sieglos XIII-XIV)», Lletres Asturianes, p. 47).

The officiality of the Asturian language and processes of diglossia

Jovellanos, already at the end of the XVIII century, spoke of Asturian as a poorly studied dialect and in danger due to its greater prestige of Spanish in urban centers and the upper classes. Thus, Jovellanos, when discussing the project for a dictionary in Asturian, pointed out how: "The printing of the Dictionary must be done at the Oviedo printing press not only to promote it, as is fair, but because only in view of the Academy can the Dictionary of a dialect unknown outside of Asturias and not well known among us be printed accurately and correctly". Understood by "us" in the context of the time to upper-class scholars who approached the Asturian language with growing interest but already had only Spanish as their mother tongue.

Current status

The current legal status of the Asturian in Asturias is the following:

- Protection range, without being recognised as an official by the Government of Asturias.

- Act No. 1/1998 of 23 March on the use and promotion of the bable/asturian, article 4, which deals with the use of the IlinguaIn paragraph 2, he said that “the use of the bable-asturian in the oral or written communications of citizens with the Principality of Asturias shall be valid for all purposes”.

- In 2005 the Asturian government approved the Asturian Social Standardization Plan 2005-2007 to enhance the use and promotion of the Asturian and Galician-Asturian.

- Francisco Álvarez-Cascos, in his Speech of Investidura at the General Board of the Principality of Asturias, on July 12, 2011, committed to “fomenting the rigorous knowledge of the Asturian”, and the new autonomous head of Culture and Sport of the Principality, Emilio Marcos Vallaure, on July 18, 2011 stated that among his great objectives is “the protection of the Asturian language”.

There is also currently a movement for the officiality of the Asturian language, in which several associations such as the Xunta Pola Defensa de la Llingua Asturiana or Iniciativa pol Asturianu, among others, and political parties, such as Izquierda Xunida d'Asturies, participate., Bloque por Asturies, UNA, PAS and the Asturian section of the PCPE, among others, which support the official status of the language and carry out extensive campaigns to achieve it.

Knowledge of Asturian

In 2017, it was estimated that 200,000 people or 19.3% of the population of Asturias spoke Asturian. 6% of the population of Asturias. According to a study by the University of the Basque Country, there are 100,000 native speakers of Asturian, 9.7% of the population of Asturias and 400,000 who have it as a second language. In a study carried out in 2003, Astur-Leonese would be the mother tongue or first language of 17.7% of the population of Asturias, 20.1% would have Astur-Leonese and Spanish as mother tongues, while 58.6% of the Asturians would have Spanish as their mother tongue.

Teaching and literacy

The teaching of Asturian in Primary Education did not begin until 1984, when six schools began to offer it as an optional subject within school hours, two or three hours a week in the middle and higher cycles of basic education (from the age of 8 to 14 years old). In the following courses it was extended to more centers until it reached practically all the public schools of Primary Education in Asturias. The acceptance figures were always very high, but the voluntariness in learning referred to in the fourth article of the Statute of Autonomy was assimilated to a very small extent by the administration, since until 1997 it was the School Councils that decided whether the school offered or not the subject, with which there were many cases of students who could not go to Asturian class, even if their parents requested it, since the center did not offer that possibility. The media gave an account of many of these parents who denounced this situation, in addition to the campaigns of citizen associations and teaching unions.

Children between the ages of 6 and 12 study Asturian at school on a voluntary basis, while between 12 and 18 it is only possible to study it optionally in some institutes. Its offer must be guaranteed in any educational center, although in many cases this is not fulfilled (in the vast majority of private and subsidized centers; despite government aid and subsidies to the latter). This situation in the present tends to change. During the 2004–2005 school year, twenty-two thousand Asturian students were able to access llingua asturiana classes in public schools and institutes in the Principality of Asturias. In the private ones the number of enrolled is testimonial.

Finally, within the new curricula adapted to the European framework, the Faculty of Asturian Philology will have a Minor in Asturian Llingua of 48 credits that will come into force in the 2010-2011 academic year and a Mention in Asturian of 30 credits for the Faculty of Teacher Training.

- 2008 data

Nearly 22,000 Asturian schoolchildren from public and subsidized education, specifically 21,457, studied Asturian (data from June 6, 2008) in the 254 centers that offer the optional subject Llingua Asturiana. Of the 22,000, the bulk, 17,500 students, are in Primary Education and some Infant classrooms, and more than 4,500 in Secondary and Baccalaureate, according to data from the General Director of Human Resources of the Ministry of Education and Science. This represents 55% voluntary school participation in the study of Asturian in Primary, and 40%, also voluntary, in Secondary.

- Course data 2009-2010

According to the data provided by the department, a total of 52,466 students study this Llingua Asturiana course, of which 51,560 receive classes in public network centers and 906 in subsidized networks.

Literature

The literary tradition, until the 20th century, is scarce: with the exception of Antón de Marirreguera (17th century), Francisco Bernaldo de Quirós Benavides, Josefa de Jovellanos and Antonio Balvidares (XVIII century), Juan María Acebal, José Caveda y Nava, Teodoro Cuesta, Pin de Pría or Fernán Coronas (XIX century and first half of the XX). Regarding this literature, the Swedish linguist Åke W: son Munthe points out «Reguera must be considered the creator of this literature, which I would call bable, and of his language; all the later singers, and no less from the linguistic point of view, come from him (Reguera's poetic traditions were collected, however, long after his death; for this reason they are also somewhat archaic in the later singers), although naturally On the other hand, they also take elements from the language of their respective terroirs, and frequently also from others with which they are in contact in one way or another, as well as a mixture with Castilian, Bablified or not. But the language of bable literature cannot, in my opinion, be described as a literary language because it has not achieved any unity, from the linguistic point of view, within that small miniature literature that, moreover, like the entire dialect, seems doomed. to a rapid disappearance".

It is from the democratization of Spain that the resurgence (Surdimientu) of literature in Asturian takes place, with authors such as Berta Piñán, Esther Prieto, Lourdes Álvarez, Ismael González Arias, Xuan Bello, Antón García, Miguel Rojo, Milio Rodríguez Cueto, Pablo Antón Marín Estrada or Martín López-Vega. All of them writers with universalist pretensions, who renounce being corseted in localist models and give the Asturian a full literary dimension. In this process, translations of foreign literature have been of great importance: Albert Camus, Tennessee Williams, Herman Melville, Franz Kafka, T.S. Eliot, Eugénio de Andrade, etc.

The most significant novels from this Surdimientu period are: Historia universal de Paniceiros, by Xuan Bello; In Search of Xovellanos, by Ismael González Arias; Imago, by Adolfo Camilo Díaz; The Incarnate City, by Pablo Antón Marín Estrada; and The soundtrack of paradise, by Xandru Fernández.

The Academy of the Asturian Language (Academia de la Llingua Asturiana, A.Ll.A) was founded in 1981, with the intention of recovering the old institution that was established in the XVIII.

Music

Virtually all traditional and modern music related to folk and rock uses Asturian in their interpretations. In traditional song, Mariluz Cristóbal Caunedo and José Manuel Collado stand out. In the field of folk, the reference groups are Llan de Cubel, Asturiana Mining Company, Felpeyu, Ástura, La Bandina'l Tombo and Tuenda. The main voices of the updated traditional song are those of Anabel Santiago, Nacho Vegas and the Valle Roso Brothers. And the most outstanding figure of jazz fusion with traditional song is Mapi Quintana. In modern music, the group Los Berrones stands out, authors of the best-selling album in Asturian in history.

The group Dixebra and more recent ones such as Skanda, Llangres, Skama la Rede, Oi! N'Ast, Gomeru o Asgaya, where the guitarist and composer of the heavy metal band Avalanch, Alberto Rionda, participated. Lately it is necessary to review singer-songwriters and groups that are closer to little like Toli Morilla and Alfredo González.

Toponymy

The toponymy in the Asturian language of the towns of the autonomous community has gained visibility in recent years. More than half of the Asturian councils would have requested the elaboration of a file on the toponymy in Asturian of their territories, many of them having been approved (in some cases jointly with the place name in Castilian and in others substituting it). The Toponymy Advisory Board is a body of the Principality of Asturias related to this task.

In September 2011, there were 49 conceyos (municipalities) with official place names in Asturian, out of the 78 that exist (See list).

Complaints of discrimination

Asturian, which has been standardized very late (the first official spelling standards were published in 1981), despite having explicit protection by the Statute of Autonomy, is not a co-official language in the Principality. Although it was introduced into the educational system in 1984 as an optional subject, it is not a vehicular language nor is it used in the Administration, although with the approval of Law 1/1998, of March 23, on the use and promotion of Bable/Asturian, Asturian citizens have the right to address the regional administration in that language. Since 1984, the teaching of Asturian has progressed, although some Asturian nationalist and language defense groups have denounced cases of discrimination. In 2001, the nationalist formation Andecha Astur filed a complaint for violation of article 510 of the Penal Code (referring to fundamental rights and public liberties) against a concerted religious school, that of the Carmelites of Villaviciosa, denouncing that the center fined the schoolchildren with 25 pesetas for each word used in Asturian. The Court of Instruction number 1 of Villaviciosa dismissed the case considering that fine for the use of Asturian did not constitute a crime. A later sentence of the Provincial Court of Oviedo also considered that the facts did not constitute a criminal offense and that, in In any case, the contentious-administrative route should have been followed.

In 2002 the Academy of the Asturian Language published a report entitled Report on the repression and non-recognition of linguistic rights in Asturias where it deals with the history and current situation of this problem.

For its part, the International Association for the Defense of Threatened Languages and Cultures (AIDLCM) visited the Principality of Asturias on November 25, 26 and 27, 2002, meeting with various institutional representatives, producing a report, Report and recommendations on the Asturian language published in 2004, which denounced the existence of great inequality regarding the exercise of linguistic rights among people who have the language as their own Asturian and those that have the Spanish language as their own and proposed various recommendations to reverse this situation: making Asturian official, promulgation of a law for the normalization of said language and its promotion, the creation of an entirely Asturian regional television channel and the recognition of the Academy of the Asturian Language as the highest scientific authority in matters related to language.

Some defenders of Asturian have accused the National Court of linguistic discrimination, where an Asturian pro-independence militant who was tried did not obtain permission to testify in Asturian, as it is not an official language. The defense accused the Court of violating article 24 of the Spanish Constitution.

Linguistic description

Asturian is a variety of Astur-Leonese which in turn forms part of the Ibero-Romance languages, typologically and phylogenetically close to Galician-Portuguese, Castilian and to a lesser extent Navarrese-Aragonese. Typologically it is a fusional inflectional language, with an initial nucleus and complement marking, and the basic order is SVO (declarative sentences without topicalization).

Phonology

The transcription is done according to the rules of the international phonetic alphabet.

- Vocals

The Asturian vowel system distinguishes five phonemes, divided into three degrees of opening (minimum, medium and maximum) and three situations (central, anterior and posterior).

| previous(palatales) | central | subsequent(s) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| closed vowels (minimum opening) | i | - | u |

| average vowels (middle opening) | e | - | or |

| Open vowels (maximum opening) | - | a | - |

- Consonants

Consonants the lips dental Alveolar palatals monitoring deaf occlusive p t t implied k occlusive sound b d g FRENCH f θ s MIN - nasal m - n - side - - l - vibrant - - r/ cede - -

Notes:

- /n/ is pronounced as a coda position.

- /g/ is usually pronounced as a sound frying even at word start.

Writing

Since the first texts, Asturian uses the Latin alphabet. In 1981, the Academy of the Asturian Language published some spelling rules. However, in Tierra de Miranda (Portugal), Astur-Leonese is written with a different standard.

The reading of the Asturian orthographic rules, and the written practice that is observed clearly shows the written language model that is pursued and that, briefly, can be summarized by saying that it is based on a vowel system of five units /a e i o u/ with three degrees of opening and double location. Similarly, it has the following consonant units: /p t ĉ k b d y g f θ s š m n ņ l ḷ r ṙ/. The model tends to a written language where the phenomenon of metaphony by -u is not frequent, nor the presence of decreasing diphthongs, general in the West, /ei, ou/. Although its writing is possible, there is neither «ḷḷ» (che vaqueira also represented, among other spellings, as «ts» in the past), nor the eastern aspiration «ḥ» (also represented as «h. »), in such a model but their corresponding «ll» and «f». Grammatically, the language offers triple gender distinction in the adjective, feminine plurals in -es, verb endings in -es, -en, -íes, íen, absence of verbs compounds (or their formation with have), etc.

The model that follows is not arbitrary, since it is offered as a fairly common possibility in previous writers and, although the strength of the central variants is a reality, the written language does not reflect an oral dialect as a model either. In the same way that the cultivation of any local variant is accepted, in teaching the speech with which the students are familiar is very present, a necessary condition to carry out an adequate pedagogy.

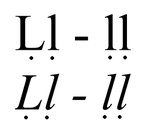

Alphabetical order and value of graphemes

(The transcription is done according to the rules of the international phonetic alphabet).

| Mayuscula | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | L | M | N | Ñ | O | P | R | S | T | U | V | X | And | Z |

| Minuscule | a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | i | l | m | n | ñ | or | p | r | s | t | u | v | x | and | z |

| Name | a | Be | ce | of | e | efe | gue | ♪ | i | ele | eme | Ene | Eden | or | pe | Erre | That one. | you | u | uve | xe | ye | zeda |

| Fonema | a | b | θ / k | d | e | f | g | - | i | l | m | n | or | p | φ/r | s | t | u | b | MIN | θ |

Digraphs

Some phonemes are represented by a digraph (pair of letters).

| Mayuscula | CH | GU + E I | LL | QU + E I | RR (between vowels) |

| Minuscule | ch | gu + e i | ll | qu + e i | rr (between vowels) |

| Name | che | - | Elle | cu | Erre double |

| Fonema | t offset | g | ~~~ | k | r |

Dialectal spellings

There are special spellings to represent allophones used in some varieties:

- The digit ( vaqueira or ch vaqueira) is used to represent sounds considered varieties of fonema ///, mainly in Western Asturian ( ingua) for example.

- The digit ts is used to represent the sound [t cancellations] (not to be confused with the previous one), which appears in words where the rest of the Asturian has -ch-/-it-, performing in the councils of Quirós and Teberga (bear, cutsu).

- The digit yy is used to represent the sound [kj], in isolated western zones, which corresponds on one side to the -y- of the rest of the domain (or -ch-), and on the other, to ll-/--/ch- initial (veryyer, fiyyu; yyegar).

- The graphema ḥ (aspired car) represents the phonema /h/, especially in the areas of the eastern asturian where the f- Latina is aspirated: (ḥaba). It also appears in some words as guaḥe or ḥispiar and can be used in several other language loans such as the case of ḥoquei.

Since the graphemes ḥ and ḷḷ do not appear in most of the typefaces commonly used both in computers and in graphic publications, they are often, and are also admitted, changed to h. and l.l respectively.

Other graphemes

To reproduce sounds from other languages, mainly Spanish and English, letters are sometimes used; j (jota), k (ka) and w (ve double ), although they are not properly part of the Asturian alphabet.

- Example: Jalisco, Kuwait.

Spelling marks

Asturian uses the following orthographic signs:

- The sharp accent (♪) above a vowel indicates in some cases tonic syllable (example: daWhat?, Call♪, Scooterc, móvil, pláganu). It is also used to differentiate monosyllables: P (substantive = father) / pa (preposition).

- The apostrophe (’) between two letters indicates that a sound was lost among them: opened the caxón (instead of)opened the caxon).

- The diresis (!) puts on the vowel u when you need to read it in sequences güe, güi: güelu, llinI did.stica.

- The short script (-) is used in front of the personal pronoun - and (Answer-and), in the composite words (politician-relixosu) and in several more specific cases.

- The long script (-) is used mainly in the transcription of dialogued texts to indicate that a character takes the word:

- What time and?

- Les two and cuartu .

- Signs of interrogation (?) are placed at the beginning and at the end of a direct interrogative sentence (U ta Xuan?).

- Signs of exclamation (!) are placed at the beginning and at the end of an exclamative phrase (What a wobble!).

- The coma (,)

- The point (.)

- The point and comma (;)

- The two points (:).

- The suspensive points (...)

- The parenthesis (())

- The quotes (“ ” or « »)

Grammar

Asturian is similar to the other Ibero-Romance varieties. An interesting peculiarity is the neuter of matter, for uncountable nouns which is a survival of the neuter gender in Asturian that has been lost outside of Astur-Leonese (except for the still-existing neuter article in Spanish "lo").

The Alphabet

The Asturian phonological system is represented in writing by means of the Latin alphabet. In this way, the Asturian uses the following letters.

| Letra | Name | Fonema |

|---|---|---|

| A, a | a | /a/ |

| B, b | Be | /b/ |

| C, c | ce | /θ/, /k/ |

| D, d | of | /d/ |

| E, e | e | /e/ |

| F, f | efe | /f/ |

| G, g | gue | /g/ |

| H, h | ♪ | - |

| I, i | i | /i/ |

| L, l | ele | /l/ |

| M, m | eme | /m/ |

| N, n | Ene | /n/ |

| Ñ, ñ | Eden | /// |

| Or, or | or | /o/ |

| P, p | pe | /p/ |

| Q, q | cu | /k/ |

| R, r | Erre | /r/, / acute/ |

| S, s | That one. | /s/ |

| T, t | you | /t/ |

| U, u | u | /u/ |

| V, v | uve | /b/ |

| X, x | xe | / |

| And, and | ye, and Greek | /,/, /i/ |

| Z, z | zeta, zeda, ceda | /θ/ |

Vocabulary

The Asturian language is the result of the development of the Latin spoken in the territory of the ancient Astures and Cantabrians. For this reason, the vast majority of words in Asturian, as in other Romance languages, come from Latin: ablana, agua, falar, güeyu, home, llibru, muyer, pesllar, pexe, práu, suañar.

To this Latin base we must add the words that entered the lexical fund of the Asturian domain from languages spoken before the arrival of Latin (substratum) or after (superstratum). Added to the influence of the substratum and superstratum are later borrowings from other languages.

Substrate

Very little is known about the language of the Asturians and Cantabrians, although it is possible that it was close to two Indo-European languages, Celtic and Lusitanian. Words from the Asturian language or from other pre-Indo-European languages spoken in this territory are grouped under the name of pre-Latin substratum. Several examples would be:

- Bedul, boroña, brincar, bruxa, canndanu, cantu, carrascu, comba, cuetu, güelga, llamuerga, llastra, llócara, matu, peñera, riega, tapín, zucar...

On the other hand, numerous celtisms were integrated thanks to the same Latin language and then passed to the Asturian as:

- Bragues, shirt, carriage, beer, sayu...

The influence of other languages after the arrival of Latin. In the Asturian, Germanisms were especially important.

- Germanisms

The Germanic peoples that were placed on the Iberian Peninsula, especially Goths and Suevos, left words like:

- Blancu, esquila, estaca, mofu, serón, spetar, gadañu or tosquila.

- Arabism

The Arabisms could reach Asturian directly, through contacts between the speakers of the Asturian domain with the Arabs or with Arab people from the south of the Peninsula. In other cases they could arrive through Castilian.

The following are some of the Arabisms of Asturian:

- Acebache, alphaya, hive, bath, ferre, galbana, mandil, safase, xabalin, zuna, zucre

Loans

The Asturian language also received a large part of its lexicon from nearby languages, such as Spanish, French, Occitan or Galician. Through Spanish, words from more distant languages also arrived.

In order of importance, Castilianisms are in first place in the list of loans to Asturian. However, in some cases, due to the great closeness between Castilian and Asturian, it is quite difficult to know if a word is a loan from Castilian, a common result of the two languages from Latin, or a loan from Asturian itself to Spanish. Some Castilianisms in Asturian are:

- Echar, antoxu, guerrilla, xamon, naesta, rexa, vanilla, xaréu...

Spanish was also used as an intermediary for the arrival of words from other languages, especially from America. For example, going through Spanish, they will arrive in words from Nahuatl (cacagüesa, chicolate, tomate), from Quechua (cóndor, llama), from Caribbean (caiman, cannibal, canoe) or Arawak (iguana, furacán).

Several words from English (esprái, fútbol, güisqui, ḥoquei, water-polo) or from other languages also passed through Spanish: boomerang (from the Australian Aboriginal languages, including English), sperm whale (from Portuguese), kaolin (from Chinese), kamikaze (from Japanese), vampiru (from Serbian) or vodka (from Russian).

From time to time, Galician loanwords are also difficult to identify, due to the proximity of this language to the more western varieties of the Asturian linguistic domain. Some words of Galician origin are usually considered as cachelos, chombada or quimada.

Gallicisms (words borrowed from French) and Occitanisms appear early, which seems to indicate that contacts with inhabitants from beyond the Pyrenees were frequent, not only through the Camino de Santiago, but also by sea. Many of these words actually belong to the marine lexicon, although most of the Gallicisms reached Asturian directly, in other cases they passed through Castilian before.

Among the Gallicisms we can mention:

- malvís, tore, ♪, xofer, ♪, You, Foina, galipote, llixeru, Month, pote, somier, tolete, vagamar, xalé, xarré...

From Occitan come words like:

- Hostel, barbecue or tolla.

Sample text

- Extract of L'ultimu home (Miguel Solís Santos)

- A scarf tremer the fayéu. The nerbatu sniffed. L'esguil desapaeció nel nieru. Hebo otru españíu, and darréu otru. L'home, entós, mientres cayía coles manes abiertes, güeyos nel infinitu y el so cuerpu remanando per tolos llas abonda blood, glayó una pallabra, una pallabra namás, que resonó y güei continua resonando na viesca y en toa Asturies: "Llibertá!"

- Spanish translation of 'The Last Man'

- 'An explosion made the beech shake. Milo flew away. The squirrel disappeared in the nest. There was another explosion, and then another one. The man, then, as he fell with his hands open, his eyes in the infinite and his body pouring everywhere a lot of blood, cried out a word, only a word, which he resonated and today continues to resonate in the forest and throughout Asturias: "Freedom!"

Comparison between variants

The Our Father in the three main variants, Spanish and Galician:

- Gallego

We who are not here, sanctified sex or your name, see or your kingdom, and let your will be done here on earth as not here. Give us hoxe or us daily bread; I forgive our offenses, as we also forgive those who have offended us; And do not let us fall into temptation, but deliver us from evil. Amen.

- Western

Pái nuesu que tas nel cielu, sentificáu sía'l tou nome. Amiye'l tou reinu, do your will voluntarily do the same on earth as in heaven. Our bread of all days give us light and forgive us our offenses the same as we make cones that we lack. Never let us fall into temptation and deliver us from evil. Amen.

- Central

Pá nuesu que tas nel cielu, sanctificáu seya'el a nome. Love him to reign, do the will the same on earth as in heaven. Give us your bread of all days and we forgive our offenses the same as we do to each other that we lack. And never let us fall into temptation, and deliver us from evil. Amen.

- East

Our Father who is in heaven, hallowed be your name. Amiye'l tu reinu, ḥágase la tu voluntá lu mesmu en tierra que' cielu. Give us today our bread of all days and forgive us our offenses the same that we do with those who lack us. And do not let us fall into temptation, and deliver us from evil. Amen.

- Castellano

Ours in heaven, sanctified be your name. Let your kingdom come. Do your will here on earth as in heaven. Give us today our daily bread and forgive our offenses, just as we forgive those who offend us. And do not let us fall into temptation and deliver us from evil. Amen.

comparative Alpi questionnaire (around 1930)

Comparative table of the situation of the different dialect variants carried out by the ALPI questionnaire (linguistic atlas of the Iberian Peninsula) is provided with the thirty years of the last century:

Question

p.305

Navelgas

(Tineo)309

Villanueva

(Teberga)313

Plains

(Castrillion)315

Felechosa

(Yesterday)329

Brochure

(Leon)321

Los Carriles

(Llanes)eye

5güeyu

['we]u]güechu

['wet cleansingu]güeyu

['we]u]güiyu

['wi]ü]güetyu

['wet]u]"oyu

[o]u]ear

5ureya

[whispering]uret ratea

[whispering]oreya

[o're]a]oreya

[o're]a]oreye

[o're]e]Oreíya

[ore’i]a]ear

5uyíu

[u']ju]o'yidu

[o’]iδu]o'yiδu

[o’]iδu]u

[o'iu]uyíu

[u']ju]I heard.

[o'jδu]Yegua

6yeugua

[']eugwa]yeugua

[']eugwa]Yegua

[']egwa]Yegua

[']egwa]Yegua

[']egwa]Yegua

[']egwa]shaft

6The eis

['eis]l'exe

[l'exe]the eixa

[the 'eirit']the exe

['e laughter]the exi

['e agile]the exa

[the 'epit'].

7xobu

['happy]xobu

['happy]♪

['λobu]l.lu

['happy]tsobu

[']sobu]♪

['λobu]knot

7noyu

['no]u]nodiu

['noδju]nuedu

['nweδu]nuibu

['nuibü]nuedu

['nueδu]nudu

['nuδu]milk

7xeiti

['xeiti]tseichi

['tseit cleani]llechi

['λetκi]Take it.

[' laughter]tseichi

['tseit cleani]Take it.

['λet ratee]Bridge

9ponti

['ponti]ponti

['ponti]puenti

['puenti]a bridge

['bridge]puenti

['puenti]Bridge

['bridge]rain

9chover

['tgilo'beR]tsover

['tso'beR]rain

['λobeR]Yover

['yobeR]tyover

[']obeR]rain

['λobeR]flame

8xama

['happy]tsapada

[tsa'pada]flame

['λama]yama

[']ama]tyama

[']ama]llapada

[λa'pada]snow

9Nievi

[njebi]Nievi

[njebi]Navi

[]ebi]snow

[Chuckles]Nievi

[njebi]snow

[Chuckles]One spoon

11one whose

['ku]aR]cuchare

[ku’tgilare]whose

[ku']aR]whose

[ka']aR]cutyar

[ku']aR]a cucharo

[a cu’tpitu]aro]avispa

13gueiespa

[gei'espa]Abraspa

[a’brjespa]abyspera

[a’bjwaits]biaspra

['bjespRa]plaster

[']espRa]abiéspara

[a'bjespara]dance

14 and 27beixar

[bei’κaR]beitsar

[bei’tsaR]dance

[bai’laR]dance

[bai’e]baitsar

[bai’tsaR]dance

[bai’λaR]woman

15to

[mu’]eR]♪

[mu’tgileR]to

[mu’]eR]to

[mu’]eR]mutyer

[mu’]eR]to

[mu’]eR]flour

22Farina

[fa’rina]... Fariña

[fa’ri]a]Farina

[fa’rina]varina

[va’rina]h.arina

[ha’rina]Everything.

22todu

[toðu]... Everything.

[toðo]too

['to:]too

['to:]tou

[tou]suit

22truxienun

[tRu’iriienun]... Trixeron

[tRi'・eron]trixoren

[tRi'κoren]truxurin

[tRu' riforin]Trayer

[tra']eren]They were

23fonun

['fonun]... They were

['were gone]foren

['foren]Vorin

['vorin']h.oron

['xoron]silbar

16xiplar

[CHUCKLING]xiblar

[gifting]xiblar

[laughter]xiblar

[laughter]xiblar

[gifting]♪

[tpitting]laurel

17xoreiru

[gilo’reiru]tsaurel

[tsau’rel]lloreu

[λo’reu]llorel

[llo’rel]laurel

[lau’rel]Iloru

[λo’ru]

Comparison of texts in Asturleonese

See more comparative tables

| Location | Linguistic block | Text | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Asturleon dialects | |||

| Talk about Carreño | Asturias | Central Asturleon | To the human beings are born llibres already equal in dignidá and drains and, pola mor of the reason and the consciousness of so, they have to behave fraternally the other colos. |

Speak of Somiedo | Asturias | Western Asturleon | Todolos human beings are born.ibres already equal in dignidá already, dotaos cumo tan of reason already consciousness, they have to behave fraternally the outgoing cones. |

Pa Pauezu | León | Western Asturleon | Todolos human beings are born.ibres already equal in dignidá already, dotaos cumo tan of reason already consciousness, they have to behave fraternally the outgoing cones. |

Cabreirés | León | Western Asturleon | To these human beings add the same books in dignidá and dreitos, and, given as they are right and conceived, they have to behave fraternally the outgoing pussy. |

Mirandés | Trás-os-Montes (Portugal) | Western Asturleon | All houman beings naze blemishes and eiguales an denidade i an dreitos. Custuituídos de rezon i de cuncéncia, dében portar-se uns culs outros an sprito de armandade. |

| Talk about transition | |||

Extreme. | Extremadura and Salamanca | You speak of transition between Asturleon and Spanish | Tolos hombris nacin libris i egualis en digniá i derechus i, comu spend reason i concéncia, ebin behavel-se comu hermanus los unus conos otrus. |

Cantabri or Montañes | Cantabria | Tolos serishuman nacin libris y eguales en dignidá y drechos and, dotaos comu are of reason and conscience, tién de behavese comu sis los unos conos otros. | |

| Other Romance languages | |||

| Portuguese | Portugal | Portuguese | All human beings nascem livres e iguais em dignitye e em direitos. Donated by razão e de consciência, devem agir uns para com os outros em espírito de fraterne. |

| Gallego | Galicia | Gallego | All of you human beings are born Ceibes and iguais in dignity and dereitos, and, endowed as they are of thirst and conscience, they must behave fraternally a cosoutros. |

| Castellano | Castilla | Castellano | All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights and, endowed with reason and conscience, they must behave fraternally with each other. |