Asteroid

The asteroids (Asteroidea) or starfish are a class of the phylum Echinodermata (echinoderms) with pentaradial symmetry, with a flattened body formed by a pentagonal disk with five or more arms. The name "starfish" essentially refers to members of the class Asteroidea. However, in its common usage the name is sometimes incorrectly applied to ophiuroids. The Asteroidea class consists of about 1,900 extant species that are distributed in all of the world's oceans, including the Atlantic, Pacific, Indian, Arctic, and Antarctic. Starfish occur in a wide range of depth, from the intertidal zone to the abyssal at depths greater than 6,000 m (meters).

Starfish are one of the best-known groups of marine animals on the seafloor. They usually have a central disc and five arms, although some species may have many more arms. The aboral or upper surface may be smooth, granular, or spiny, and is covered with overlapping plates. Many species are brightly colored in various shades of red or orange, while others are blue, gray, or brown. They have tube feet operated by a hydraulic system and a mouth in the center of the oral or lower surface. They feed opportunistically, preying mainly on benthic invertebrates. Several species have special feeding behavior, including filter feeding and adaptations to feed on specific prey items. They have complex life cycles and can reproduce both sexually and asexually. Most have the ability to regenerate missing or damaged arms. They have several important functions in ecology and biology. Species such as Pisaster ochraceus became widely known as examples of the concept of keystone species in ecology. The tropical species Acanthaster planci is a voracious predator of coral throughout the Indo-Pacific region. Other starfish species, such as members of the family Asterinidae, are frequently used in developmental biology.

Taxonomy and evolutionary history

Asteroidea is a class within the phylum Echinodermata, which is made up of a large number of species. Like other classes in that group, its members are characterized by having radial symmetry as adults, usually pentaradial symmetry. However, during their early stages of development, the larvae are bilaterally symmetrical. Other features of adults include a water-bearing vascular system, and calcareous skeletons consisting of flat plates connected by mutable collagenous meshwork. Asteroids are characterized by a central disk with a number of radiating arms, typically five. The ossicles that form the hard element of the skeletal structure extend from the disc over the arms in a continuous arrangement that forms a broad base for the arms. In contrast, in ophiuroids the disc is clearly distinguished from the long, slender arms..

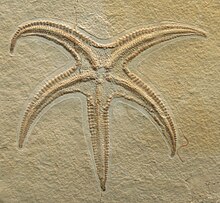

Asteroidea are underrepresented in the fossil record, partly because the hard parts of the skeleton break away when the animal decomposes, or because the soft tissues break down into distorted, unrecognizable remains. Another reason may be that most of the Asteroidea live on hard substrates where the conditions for fossilization are not favorable. The first known asteroids date back to the Ordovician. In the two main mass extinction events during the Late Devonian and the Late Permian, many species went extinct, but others managed to survive. These diversified rapidly within 60 million years during the Early Jurassic and early part of the Middle Jurassic.

Diversity

The class of asteroids is made up of the following orders:

- Order Brisingida (2 families, 17 genera, 111 species)

- The species of this order have a small inflexible disk and between six and 20 long and thin arms used for suspension feeding. They have a single series of marginal plates, a ring of merged disk plates, without actinal plates, an outcropping column that looks like a reel, reduced abactinal plates, crossed pedicelaries, and several series of long thorns in the arms. They live almost exclusively in deep-sea habitats of more than 6,000 meters, although some live in shallow waters of Antarctica. In some species, the ambularchal feet have rounded limbs without suction cups.

- Order Forcipulatida (6 families, 63 genera, 269 species)

- The species of this order have distinctive pedicelaries that consist of a short stem with three skeletal bones. They tend to have robust bodies. They have outgoing and ventous feet with flat ends. The order includes well-known species, common in temperate regions, as well as species of cold and abysmal waters.

- Order Paxillosida (7 families, 48 genera, 372 species)

- The species of this order lack an anus and do not have suction cups in their outpatient feet. They do not develop the brachiolaria stage during the phase of their larval development. They have marginal plates, and they have sesile pedicelaries. Most of them live in the soft bottom areas of sand or mud.

- Order Notomyotida (1 family, 8 genera, 75 species)

- These asteroids inhabit deep waters and have flexible arms. The internal back-lateral surface of the arms contains longitudinal muscle bands features In some species, out-of-arms lack suction cups.

- Order Spinulosida (1 family, 8 genera, 121 species)

- Most of the species of this order lack pedicelaries, and all have a delicate skeletal arrangement with small marginal plates on the disc and arms. They have numerous groups of low thorns on the aboral surface (superior).

- Order Valvatida (16 families, 172 genera, 695 species)

- Most of the species of this order have five arms and ambulatory feet. They have noticeable marginal plates on the disc and arms, and the main pedicelaries look like tweezers.

- Order Velatida (4 families, 16 genera, 138 species)

- This order of asteroids is composed mainly of deep sea stars and cold waters, often with a global distribution. They have a star or pentagonal shape, with five to fifteen arms. Most have undeveloped skeletons.

Description

Sea stars tend to have a radially symmetrical appearance and usually have pentaradial symmetry as adults. However, the evolutionary ancestors of echinoderms are thought to have had bilateral symmetry. Currently, starfish, like other echinoderms, only exhibit bilateral symmetry in their larval forms.

Most sea stars have five arms radiating from a central disk. However, several groups of asteroids, such as the family Solasteridae, have 10 to 15 arms, while some species, such as Labidiaster annulatus from Antarctica, can have up to 50 arms. It is not unusual for species that typically only have five arms to have six or more arms due to developmental abnormalities.

The surface of starfish has components that resemble plates of calcium carbonate known as ossicles. These form the endoskeleton, which can have various forms, externally expressed as a variety of structures such as spines and granules. These may be arranged in characteristic patterns or series, and their architecture, individual shapes, and locations are used to classify the different groups within the class Asteroidea. Terminology referring to the location of starfish body components is generally based on reference to the mouth, to avoid incorrect assumptions of homology with the dorsal and ventral surfaces of bilateral animals. The lower surface is often referred to as the oral or actinal surface, while the upper surface is known as the aboral or abactinal side.

The body surface of starfish has several structures that comprise the basic anatomy of the animal, and can sometimes aid in its identification. The madreporite plaque can be easily identified by the light circle that lies slightly off center of the central disk. This porous plate is connected, through a calcified channel, to the hydraulic vascular system in the disc. Its function is, at least in part, to provide additional water for the animal's needs, including make-up water for the aquifer vascular system. The anus is also located slightly off center of the disc, near the madreporite plate. On the oral surface, an ambulacral groove runs down each arm, on each side of which extends a double row of unfused ossicles. Tube feet extend into these through notches and are internally connected to the aquifer vascular system.

Several groups of asteroids, including the orders Valvatida and Forcipulatida, possess small structures known as pedicellaria, which bear some resemblance to valves. These occur widely over the surface of the body. In asteroids of the order Forcipulatida, such as those of the genera Asterias and Pisaster, the pedicelaria are produced in tufts resembling pom-poms at the base of each spine, while in species from the family Goniasteridae, such as Hippasteria phrygiana, the pedicellariae are more widely distributed over the body surface. Although not all of the functions of these structures are known, it is thought that some help in the defense of the animal, while others help in feeding or eliminating organisms that try to establish themselves on the surface of the starfish. Labidiaster annulatus from Antarctica has large pedicelaria which it uses to capture active krill prey. Stylasterias forreri from the North Pacific has been observed catching small fish with its pedicelaria.

There are also other types of structures whose occurrence varies by taxon. For example, members of the family Porcellanasteridae have additional sieve-like organs located between the series of lateral plates, which are thought to generate currents in the burrows made by these starfish.

Internal anatomy

Like echinoderms, starfish possess a hydraulic water-vascular system that aids in locomotion. This system includes many projections, known as tube feet, on the arms of the starfish; These serve for locomotion and feeding. Tube feet emerge through openings in the endoskeleton and are expressed externally by open grooves that run along the oral surface of each arm.

The body cavity also contains a circulatory system, known as the hemal system. Blood channels form rings around the mouth (the oral blood ring), closer to the aboral surface, and around the digestive system (the gastric blood ring). A portion of the body cavity, the axial sinus, connects the three rings. Each arm also has hemal canals running alongside the gonads. These canals have blind ends with no continuous circulation of blood.

At the end of each arm is a small simple eye (or ocellus), which allows one to perceive the difference between light and dark, which is useful for detecting moving objects. Only a part of each ocellus cell it is pigmented (hence a red or black color), with no cornea or iris.

Body wall

The body wall is composed of a thin outer epidermis, a thick dermis made of connective tissue, and a thin inner peritoneum containing circular and longitudinal muscles. The dermis contains loosely organized ossicles (bone plates). Some have external granules, tubercles, and spines, sometimes arranged in definite patterns, and some are specialized as pedicellaria. It may also include papules, thin-walled bumps that pass through the body wall, extend into the surrounding water, and they have a respiratory function. These structures are supported by collagenous fibers oriented perpendicular to each other and arranged in a three-dimensional network with the ossicles and papules in the interstices. This arrangement allows both the flexion of the arms of the starfish, as well as the rapid onset of the necessary rigidity for actions carried out under pressure.

Digestive System

The mouth of a starfish is located in the center of the oral surface and opens, through a short esophagus, into a cardiac stomach in the first instance, and then into a pyloric stomach in the second instance. Each arm also contains two pyloric caeca, which form long branching tubes from the pyloric stomach to the outside. Each pyloric cecum is covered by a series of digestive glands, which secrete digestive enzymes and absorb nutrients from food. A short intestine extends from the upper surface of the pyloric stomach to the opening of the anus near the center of the upper body.

Many sea stars, such as those of the genera Astropecten and Luidia, swallow their prey whole and begin to digest it in the stomach before passing it on to the pyloric caecum. However, a large number of species have the ability to evert the cardiac stomach outward to engulf and digest food. In these species, the cardiac stomach retrieves the prey, and then passes it to the pyloric stomach which always remains internal. Waste is excreted through the anus on the aboral surface of the body.

This ability to digest food outside of its body allows starfish to hunt prey much larger than the size of its mouth. It feeds on clams, oysters, arthropods, small fish, and gastropod molluscs. Some starfish are not fully carnivorous, and may supplement their diet with algae or organic detritus. Some of these species graze, but others trap food particles from the water in sticky mucous strands that can be dragged into the mouth along ciliaous slits.

Nervous system

Although starfish lack a centralized brain, their bodies have complex nervous systems under the coordination of what might be called a distributed brain. They have a network of interlocking nerves, a nerve plexus, which lies within as well as under the skin. The esophagus is also surrounded by a central nerve ring, which sends radial nerves into each of the arms, often in parallel with the branches of the aquiferous vascular system. They all connect to form a brain. The nerves of the central nervous ring and the radial nerves are responsible for coordinating the starfish's balance and steering systems.

Although starfish do not have many well-defined sensory inputs, they are sensitive to touch, light, temperature, orientation, and the state of the surrounding waters. Tube feet, spines, and pedicelariae of starfish Sea turtles are sensitive to touch, while the ocelli at the ends of the arms are sensitive to light. Tube feet, especially those found at the tips of the arms, are also sensitive to chemicals, and this sensitivity It is used in locating odor sources, such as food.

Ocelli consist of a mass composed of light-responsive pigmented epithelial cells, and narrow sensory cells located between them. Each ocellus is covered by a thick transparent cuticle that provides protection and acts as a lens. Many sea stars also have individual photoreceptor cells distributed over their bodies, and are capable of responding to light, even when their ocelli are covered.

Locomotion

Starfish move using a water vascular system. Ambient water enters the system through the madreporite plate. It then circulates from the stony canal to the annular canal and the radial canals. Radial canals carry water to the ampulla (reservoir) in the tube feet. Each foot consists of an internal ampulla and an external podium, or "foot". When the blister is compressed, it forces water onto the podium, which expands until it makes contact with the substrate. In some circumstances, the tube feet appear to function as levers, but when moved on vertical surfaces, they form a traction system. Although the podium resembles a suction cup, the gripping action is accomplished by the secretion of adhesive chemicals. instead of aspiration. Other chemicals and podial contraction allow it to be released from the substrate.

Tube feet attach to the surface and move in a wave, with one section of the body attaching to the surface, as others loosen it. Most starfish can't move very fast; for example, Dermasterias imbricata can only move about 15 cm (centimeters) in a minute. Some species in the burrowing genera Astropecten and Luidia they have points instead of suckers on their long tube feet and are capable of moving at much higher speeds on the seafloor. Luidia foliolata for example can move at a speed of 2.8 m per minute.

Respiration and excretion

Respiration occurs mainly through the tube feet and through the papules that dot the surface of the body. The oxygen in the water is distributed throughout the body primarily by the fluid in the main body cavity; the hemal system may also play a minor role.

Since it has no separate excretory organs, excretion of nitrogenous waste occurs via tube feet and papules. Body fluid contains phagocytic cells, coelomocytes, which are also found within the hemal system and aquifer vascular system. These cells engulf waste materials, which eventually travel to the tips of the wheals where they are expelled into the surrounding water. A part of the waste can be excreted by the pyloric glands with the feces.

Sea stars do not appear to have a mechanism for osmoregulation, and keep their body fluids at the same salt concentration as the surrounding water. Although some species can tolerate relatively low salinity, the lack of an osmoregulation system probably explains why starfish are not found in freshwater, or even estuarine environments.

Secondary metabolites

Various toxins and secondary metabolites were extracted from a number of starfish species. Research on the efficacy of these compounds for possible pharmacological or industrial use is carried out in many countries.

Life Cycle

Starfish have the ability to reproduce sexually and asexually.

Sexual reproduction

Most starfish species are dioecious, meaning there are males and females. It is usually not possible to distinguish them externally, since the gonads cannot be seen, but their sex is apparent during spawning. Some species are simultaneous hermaphrodites (produce eggs and sperm at the same time). In some of them, the same gonad, called ovotestis, produces both eggs and sperm. Other starfish are sequential hermaphrodites, some of which are protandrous. That is, the juveniles are initially male but become female as they age, as occurs in the species Asterina gibbosa for example. Others are protogynous and convert from female to male as they age. In some species, when a large female reproduces by division, the smaller individuals she produces become males. When they grow large enough, they change back into females.

Each arm has two gonads that release gametes through openings, called gonoducts, located in the central disc between the arms. In most species fertilization is external, although some species know internal fertilization. In most species, the eggs and sperm are released into the water (free spawning) and the embryos and larvae that result from external fertilization are part of the plankton. In other species, the eggs develop attached to the underside of rocks. In certain species, the females incubate their eggs, covering them with their body, or holding them in special structures. These structures include chambers on the aboral surface, the pyloric stomach (Leptasterias tenera) or even the gonads themselves. Sea stars that incubate their eggs by covering them with their bodies usually elevate their central disc, assuming a hunched posture. There is also a species that incubates a portion of its young and delivers the remaining eggs that do not fit in the pouch. In these brooding species, the eggs are relatively large and yolked, and usually, though not always, develop directly into a small starfish, without going through a larval stage. Developing hatchlings are called "lecithotrophic" as they derive their nutrition from the egg yolk, unlike larvae which feed planktotrophically. In an intragonadal brooding species, hatchlings obtain their nutrition by feeding on other eggs and embryos in the gonadal brooding pouch. Brooding is particularly common in deep-sea and polar species, which live in environments less favorable for larval development, and in the smaller species that produce few eggs.

Reproduction takes place at different times of the year depending on the species. To increase the chances that their eggs will be fertilized, starfish may synchronize spawning, gathering in groups, or forming pairs. This latter behavior is called pseudo-copulation, and the male climbs on top of the female, placing his arms between his, and emits sperm into the water. This stimulates the emission of eggs. Starfish can use environmental cues to coordinate spawning timing (day length to indicate the correct time of year, sunrise or sunset to indicate the correct time of day), and chemical cues to indicate their readiness. others. In some species, adult females produce chemicals to attract sperm in seawater.

Asexual reproduction

Some species of starfish also reproduce asexually as adults, either by fission of their central discs or by autotomy of their arms. The type of reproduction depends on the genus. Among starfish that regenerate entire bodies from severed arms, some can do so, even from fragments as little as 1 cm (centimeter) long. Splitting of the starfish, or through its disks or arms, is often accompanied by changes that facilitate partitioning.

The larvae of several species of starfish also have the ability to reproduce asexually. They can do so by autotomy of parts of their bodies or by budding. When there is an abundance of food, the larvae favor asexual reproduction. rather than developing directly. Although this costs time and energy, it will allow a single larva to reproduce into multiple adults if conditions are right. Various other reasons trigger similar phenomena in the larvae of other echinoderms. These include the use of tissue that is lost during metamorphosis, or the presence of predators that prey on the larger larvae.

Larval development

Like other echinoderms, starfish undergo deuterostomic (embryonic) development, a feature they share with chordates (including vertebrates), but not with most other invertebrates. Their embryos initially develop bilateral symmetry, which seems to reflect their probable common ancestry with chordates. However, further development takes a very different path, when the larva settles out of the zooplankton and develops the characteristic radial symmetry. As the organism grows, one side of its body grows larger than the other, eventually absorbing the smaller side. After that, the body is formed into five parts around a central axis until the starfish has its radial symmetry.

Sea star larvae are ciliated, free-swimming organisms. The fertilized eggs develop into bipinaries and later (in most cases) into brachiolaria larvae that either grow by feeding on the egg yolk, or by trapping and eating other plankton. In both cases, they live as plankton, suspended in the water and swim by beating their cilia. The larvae are bilaterally symmetrical and have a distinct left and right side. Over time, they settle to the bottom of the sea, undergo complete metamorphosis, and become adults.

Longevity

The lifespan of starfish varies considerably between species, and is generally longer in larger species. For example, Leptasterias hexactis, which weighs 20 g as an adult, reaches sexual maturity in two years and has a life expectancy of about 10 years, while Pisaster ochraceus, whose adult weight is 80 g, reaches maturity in five years and can live up to 34 years.

Regeneration

Some species of starfish have the ability to regrow missing arms and can grow new limbs. Some species also have the ability to regrow a new central disc from a single arm, while others require that at least a portion of the central disc be connected to the detached part. Regeneration can take several months or years. Starfish are vulnerable to infection in the early stages after the loss of an arm. A severed limb lives on stored nutrients until it regrows a central disc and mouth and is capable of feeding again. Apart from the fragmentation that is carried out for breeding purposes, the division of the body can occur accidentally after detachment by a predator, or the arm can be actively ejected during an escape response, a process known as autotomy. The loss of body parts is accomplished by the rapid softening of a special type of connective tissue in response to nerve signals. Most echinoderms have this type of tissue.

Food

Most starfish species are generalist predators, feeding on molluscs such as clams, oysters, snails, or any other animal too slow to evade attack (for example, other echinoderms or near-dead fish). Some species are detritus feeders, feeding on decomposing animal and plant matter, or on organic sheets attached to substrates. Others, such as members of the order Brisingida, feed on sponges or plankton and suspended organic particles. Acanthaster planci consumes coral polyps, and is part of the food chain in coral reefs. From time to time, explosive outbursts from these stars occur that can cause severe damage to coral reef ecosystems.

Some starfish have special organs that make it easier to capture prey and feed; Pisaster brevispinus, from the Pacific coast of the United States, can use a set of specialized tube feet to dig deep into soft substrates and extract its prey (usually clams). Grasping shellfish, the sea star slowly opens the shell of the prey, exhausting its adductor muscle, and then inserts its everted stomach into an opening to devour the soft tissues. For the everted stomach to gain entry, the gap between the valves need only be a fraction of a millimeter wide.

Distribution

Currently, more than 1,900 species of starfish are known to exist. Echinoderms maintain a delicate internal electrolyte balance in their bodies, and this is only possible in a marine environment. This means that starfish occur in all of Earth's oceans, but are not found in any freshwater habitats. The greatest variety of species is found in the tropical Indo-Pacific. Other regions known for their great diversity include the tropical and temperate zones of Australia, the tropical eastern Pacific, and the cold-temperate waters of the North Pacific (from California to Alaska). All starfish live at the bottom of the sea, but their larvae are planktonic, which allows them to disperse to new locations. Habitats range from tropical coral reefs, rocks, mud, gravel, and sand, to kelp forests, seagrass beds, and the dark bottom of deep waters.

Threats

Starfish and other echinoderms pump water directly into their bodies through the aquifer vascular system. This makes them vulnerable to all forms of water contamination, as they have little ability to filter the toxins and contaminants it contains. Oil spills and similar events often affect echinoderm populations and have far-reaching consequences for the ecosystem.

Another threat that starfish frequently suffer is when they get too close to the coast, tourists make the mistake of taking them out of the water to contemplate them and take photos of them, without knowing that by doing so they cannot perform their gas exchange for respiration and in a short time they will die due to poisoning, in other words, they drown.[citation required ] Starfish and other echinoderm species are best kept from their aquatic habitats.

They are also used as keepsakes or souvenirs and are extracted to be sold. They are used in aquariums.

Further reading

- Blake DB, Guensburg TE; Implications of a new early Ordovician asteroid (Echinodermata) for the phylogeny of Asterozoans; Journal of Paleontology, 79 (2): 395-399; March 2005.

- Gilbertson, Lance; Zoology Lab Manual; McGraw Hill Companies, New York; ISBN 0-07-237716-X (4th edition, 1999).

- Shackleton, Juliette D.; Skeletal homologies, phylogeny and classification of the earliest asterozoan echinoderms; Journal of Systematic Palaeontology3 (1): 29-114; March 2005.

- Sutton MD, Briggs DEG, Siveter DJ, Siveter DJ, Gladwell DJ; A starfish with three-dimensionally preserved soft parts from the Silurian of England; Proceedings of the Royal Society B – Biological Sciences; 272 (1567): 1001–1006; 22 May 2005.

- Hickman C.P, Roberts L.S, Larson A., l'Anson H., Eisenhour D.J.; Integrated Principles of Zoology; McGraw Hill; New York; ISBN 0-07-111593-5 (13th edition, 2006).

Gallery

Contenido relacionado

Compsognathus longipes

Thalassemia

Distichlis