Aspis

The aspis (Ancient Greek ἄσπις, AFI [aspis]) is the generic term for the word shield. The aspis was commonly worn by ancient heavy infantry at various periods in Greek history, from Minoan times to the 4th century a. c.

The hoplon (τὸ ὅπλον, [hoplon]) was used by Greek heavy hoplite infantry and cavalry, between the centuries VIII a. C. and IV century B.C. c.

It underwent numerous evolutions in the material, the shape and the means of apprehension, adapting to the new offensive weapons that had greater penetrating power, manufacturing techniques and the various types of combat formations practiced by combatants.

Circular in shape, it was approximately 90 to 110 cm in diameter and consisted of a large bowl and a heavily reinforced, almost flat rim. It consisted of sheets of wood glued together. The interior was lined with fine leather, had a bronze clamp in the center, which was riveted, and a leather strap on the edge. The exterior of the shield could be covered with a bronze sheet, or painted and decorated. It weighed between 6 and 8 kg.

Minoan period (2nd millennium BC)

- The aspis in the form of 8

Shield made of perishable materials and formed by a wooden frame domed in two superimposed lobes, giving it a vague figure of 8 shape on which oxen skins are sewn. Tensioned and dried leather has the property of being more resistant to the penetration of arrows, even spears. It was suspended on the back by the télamon, a leather strap, which left the combatant's hands free. Placed in front during the confrontation, the shield was thrown back on the back in case of displacement of the troop or in case of flight.

"As Hector fled, the dark, bulging leather trim lashed at his ankles and neck." This is how Homer describes Hector's huge shield. There are many other references to those great shields: Ajax's shield was like a city wall; Agamemnon's could protect a man from both sides.

The Homeric shield is sometimes described as round. In Mycenaean art it is very rare to find round shields. However, the Sea Peoples of the 12th century B.C. C. and Homer's contemporary Greeks used them. However, they were not proper body shields. The poet was probably referring to shields with curved edges, such as the figure-of-eight.

Mycenaean period (second half of the 2nd millennium BC)

- The aspis in the shape of a tower

The figure-8 aspis gradually disappeared after 1400 BCE. C. and another type of shield based on the same materials made its appearance. This aspis-tower was a large weapon, about the height of a man, rectangular in shape, rounded at the top and bulging along a vertical line. It was also made of oxhide (up to seven layers) sewn to a wooden frame, sometimes with the addition of a bronze plate and supported by télamon.

Circa 1200 B.C. c

At this time, a shield appeared rounded at the top and cut at the bottom, smaller than the «8» or «tower» models.

Building a shield

The shields described in the Iliad consisted of several layers of leather, probably glued together and sewn to a wicker weave. The stitching is clearly represented in the Knossos paintings. It had a large bulge, probably made of bronze and rawhide or some similar material. The edges were so curved inward that the warrior was literally inside his shield. One of Homer's shields has two "rods." It's definitely tensioners. These rods were placed inside and were necessary to maintain the shape of the shield.

9th-8th century BC. c

- The new shield

The Mycenaean figure-eight shield remained in use until the 8th century BCE. C. in the areas of Greece that survived the cataclysms of the XII century BC. c.

The Dorians, who settled in southern Greece around 1050 B.C. C., they probably brought a round shield with a central handle. This shield underwent several modifications during the VIII century BC. C.: a bracelet was fixed in the center and the handle was moved to the edge. Said shield is the one that made possible the rigid formation of the phalanx. Half of the shield protruded from the left side of the warrior. If the man on the left came closer, he was protected by the protruding part of the shield, thus guarding the defenseless side of him. Later shields sometimes had a leather curtain hanging down to protect the warrior's legs from darts and arrows.

- The cut shield

This was the most widespread model during this period. Suspended on the back and made of leather-covered wood, it was large in size, rounded at the top and bottom, and featured two cutouts across halfway up.

VII-IV century BC. c

Hoplon

The hoplite's aspis koilè (commonly called a hoplon)

Literally, the word hoplon means:

το όπλο - to Hoplo (n): the original meaning was: «tool», «instrument»; later the meaning was that of war tool = weapon. τα όπλα - ta Hopla (pl.) : tools of war = mainly referring to protective armaments, which could also include weapons (see below).

το όπλον - to Hoplon : (later generic use) tool of war, including all kinds of weapons (see below).

το όπλον - to Hoplon : (old main meaning) the type of shield Greek heavy infantry used in the hoplite phalanx (Οπλιτική Φάλαγξ); the hoplite (Οπλίτης) took his name from his shield (Οπλον).

The term «weapon», in a generic sense, was used, according to many historians, improperly by contemporary literature to designate this type of shield, since the ancient Greeks never gave that word that meaning. This error comes, they say, from the fact that it was mainly this shield that allowed the appearance of the hoplite and the phalanx and that it was the weapon par excellence of this warrior. Although this statement is not unanimous among military historiography, it is widely accepted.

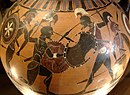

Made its appearance in the VII century B.C. C., the aspis koilè (hollow shield) was a round shield from 90 cm to one meter in diameter, domed and whose grip system was revolutionary for the time. Supported by the entire forearm, it allowed a firm and comfortable fixation during combat. It consisted of a wooden frame covered by a bronze plaque decorated with an emblem that identified the combatant and the city for which he was fighting. These paintings could represent animals (snake, bird, lion, etc.), mythological figures (gorgon, centaur, Pegasus, etc.) or a letter (such as the inverted "V" representing the capital "λ" (lambda) of Lacedaemon (Sparta)) among others. This front face also had a spiritual function, since it served to return bad luck to the enemy. In the center of the internal face of the shield covered with leather, an anatomically worked bracer (porpax) was fixed, in which the forearm slid. The grip (antilabè), attached near the edge, was made of leather or rope. The set was completed with a cord near the inner edge through doweled eyelets and which served to hang the shield. Sometimes also a piece of striped leather, also decorated, was fixed on the lower part, intended to offer better protection of the thighs.

Weighing around 8 kg, it was a weapon reserved for heavy infantry, which was made up of hoplites. At the time of the phalanx assault, the aspis koilè, held by the left arm folded in front of the body, protected its wearer from the chin to the top of the legs. Thanks to its original grip system, it allowed a push to be applied during the crash to try to knock down the enemy lines and, in the continuation of the combat, a great freedom of movement.

Variant of aspis koilè

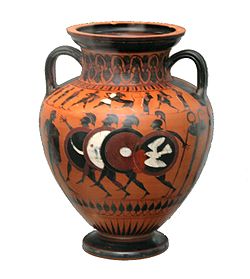

There are several representations (paintings on vases, figurines) from this period with a modified model of the aspis koilè with cut lateral edges, but no specimen has yet been found, perhaps because it was made of perishable materials.

This assumption is contradicted by the Prometheus Painter's depiction of the amphora, which dates to the mid-VI century BCE. C. (see below). These cutouts served to facilitate the passage of the spear, whose shaft got stuck between the body and the right elbow stuck against it during the assault; all this so that the ranks of the combatants were kept tight. This way of fighting during the clash of two phalanxes would be very different from that visible on the Olpe de Chigi dating from around 650 BC. C. and in which the hoplites have the spear raised and could represent an evolution, prefiguring the type of formation of the Macedonian phalanx.

Pelta: 6th-4th century BC. c

The pelta was a light shield carried by the Thracian peltast, a light infantry fighter. It had the shape of a crescent (concave side facing up) and was made of a wooden frame, often wicker, covered in goat or lambskin. Like the aspis koilè, its external face bears an emblem, often a geometric drawing that can also be more representative (snake, eye, crescent, etc.).

The shields of Olympias

After the battle it was customary for the victorious general to dedicate a shield with an inscription to one of the shrines. Many of these shields have been found at Olympia. Some have the entire front lined with bronze, others only the rim. All non-metallic parts of these shields have disappeared, although many of the interior fittings have been discovered. These were fixed in the center of the shield with rivets, which were then adjusted at the front. The soul of the shield was made of wood, with a garrison of bronze or oxhide.

Several of Olympia's shields have the fittings attached directly to the reverse of the bronze garnish. Such shields were made especially for offerings, as they would have been useless in battle. It has been suggested that they were used to deflect blows, but such a theory is at odds with the essential purpose of the phalanx. Each hoplite was supposed to protect the defenseless side of the neighbor from him, not deflect the projectiles thrown at him.