Arthropoda

The arthropods (Arthropoda, from the Greek ἄρθρον, árthron, «joint» and πούς, poús, «foot»), constitute the most numerous and diverse phylum of the animal kingdom (Animalia). The group includes invertebrate animals endowed with an external skeleton and jointed appendages; insects, arachnids, crustaceans and myriapods, among others.

There are more than 1,300,000 species described, mostly insects (estimated at 941,000 to 1,000,000 species), representing at least 80% of all known animal species. They are important members of marine, freshwater, terrestrial and aerial ecosystems. Several groups of arthropods are perfectly adapted to life in dry environments, just like the amniotic vertebrates and unlike all other animal phyla, which are aquatic or require moist environments.

Although there is no specialty of zoology that specifically studies all arthropods as a whole, there are sciences that specifically study insects (entomology), arachnids (arachnology), and crustaceans (carcinology).

Origin

Arthropods were traditionally classified together with annelids within the clade Articulata. Therefore, it was believed that the earliest arthropods might have been similar to annelids; although since fossil remains of annelids were rare, the classification of arthropods in Articulata was based primarily on morphological similarities.

The extensive arthropod fossil record and molecular analyzes rule out grouping in Articulata, including arthropods in the Ecdysozoa clade; and to the annelids, in Spiralia. Currently, it is thought that the first arthropods were small, segmented animals with appendages; called lobopods. These animals, among other groups of uncertain classification, are thought to represent various taxa in the stem group of the phylum Arthropoda.

On the other hand, it has been proposed that certain organisms belonging to the Ediacaran biota (from 555 million years ago) are related to arthropods. These animals from the Ediacaran period are "pseudo-bilateral& #3. 4; that have been included within the Proarticulata group, such as the genera Dickinsonia, Spriggina and Vendia. Although they have a different segmentation than the current arthropods.

Features

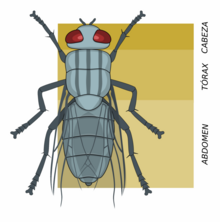

Arthropods constitute one of the great phyla of the animal kingdom, subdivided into various classes, some of which have a large number of genera and species. They are named in this way because they are equipped with articulated legs. The entire body of arthropods is made up of several segments joined together by means of articular membranes.

Despite their great variety and disparity, arthropods have fundamental morphological and physiological characteristics in common:

- Presence of articulated appendices showing enormous evolutionary plasticity and leading to the most diverse structures (patas, antennas, gills, lungs, jawbones, queliceros, etc.).

- Presence of an external skeleton or exoskeleton that move periodically. Since various pseudocellomads also move the cuticle, some authors relate arthropods to nematodes and related groups, in a nail called Ecdysozoa.

- Body consisting of repetitive segments, phenomenon known as metamería, so the body appears constructed by repeated modules along the antero-posterior axis. Segmentation is accompanied by regionalization or tagmatization, with division of the body in two or three regions in most cases. Because of this nature they have traditionally been related to the anelids that are also metamerized animals; but the defenders of the Ecdysozoa clove argue that it is a case of evolutionary convergence (see Articulata and Ecdysozoa, and in this same article the section Filogenia).

Exoskeleton

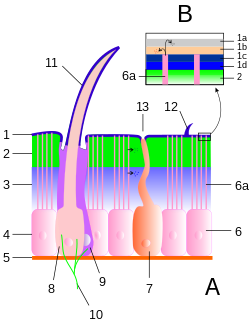

The exoskeleton of arthropods is a continuous cover called the cuticle, which extends even through the two ends of the digestive tract and through the respiratory tract or cavities, and which is located above the epidermis (called in these for that reason hypodermis), which is what secretes it.

The composition of the exoskeleton is glycopeptide (with a carbohydrate part and a peptide part). The main and most characteristic component belongs to the first of these two types, and is chitin, a polysaccharide derived from the amino sugar N-acetyl-2-D-glucosamine that is also found, for example, in the cell wall of fungi. In many cases, the consistency of the exoskeleton is enhanced by the addition of mineral substances, as in the case of crabs and other decapod crustaceans whose cuticle appears calcified, due to the deposit of calcium carbonate.

The thickness and hardness of the cuticle is not the same throughout its length. On the contrary, it appears forming hardened areas called sclerites, separated or joined together by thinner and more flexible areas. The sclerites receive complex denominations that vary in each group, but in a general way those with a dorsal location are called tergites; sterni, those of ventral location; and pleurites, the sides. There may also be ridges of the exoskeleton developed inwardly called apodemas and others called apophyses, both invaginations of the body wall form rigid processes that serve for the insertion of muscles and to give strength or rigidity to the exoskeleton.

The exoskeleton is structured in the following layers:

- Epicuum: Very thin, stratified in turn and with hydrophobic properties that give it a waterproofing function. It is composed of proteins and lipid substances such as waxes. Where it is thinner the exchange of substances is facilitated, for example perspiration.

- Procution: It is the main and thickest part of the cuticle. It is formed in turn by two layers:

- Exoculic: This part is the most unequal and rigid thickness. Its hardness derives from the presence of phenolic compounds that link the other polymers. Abunda in the sclerites and is thinner or absent in the joint areas.

- Endocundar: Thick, but at the same time flexible and thicker than the exocuculus.

The cuticle is very frequently covered with setae (hairs) of various functions, including tactile sensory.

The coloration of arthropods usually depends on the cuticle. Color pigments or guanine crystals are deposited in the procuticle. The epicuticle may have fine striations that produce physical (not chemical) colors, such as the metallic or iridescent appearance of many insects.

Ecdysis

The external skeleton has a disadvantage and that is that, in order to grow, the animal must get rid of it. It does so in a hormonally controlled process of ecdysis or moulting. The hypodermis secretes enzymes that soften and partly digest the lowermost layer of the cuticle (the endocuticle), causing the rest to fall off. Immediately the secretion of a new cuticle begins, first the epicuticle and then, below it, the procuticle. Until this new covering hardens, the animal is relatively defenseless, with less chance of escape or resistance. The entire molting process is hormonally controlled; ecdysone or "molting hormone" is the substance responsible for these changes to occur. The successive phases of the animal's existence between moulting and moulting are called stages or instars. This trait is shared by arthropods with some other phyla, such as nematodes which also have a cuticle and molt.

Appendices

The appendages are articulated expansions of the exoskeleton, inside which are located the striated muscles that, attached to the joints, provide them with versatility and speed of movement. The articulated pieces that form the appendages are called artejos (a word that derives from the Latin article, "articulated").

There are two basic types of appendages: uniramous, formed by a single axis, typical of terrestrial arthropods (arachnids, myriapods and insects); and the birameans formed by two axes and typical of aquatic arthropods (trilobites and crustaceans). There is no agreement on which was the ancestral appendage.

In the course of evolution there has been a tendency to restrict the appendages to certain regions of the body and to specialize them for different functions. The head appendages are adapted for sensory perception, defense, and for manipulating food; those of the thorax are used for locomotion and swimming; the abdominals perform respiratory and reproductive functions, such as retaining eggs or clinging to the partner during copulation. Others have been modified in such a way that it is difficult to recognize them as such (spider spinnerets, scorpion combs).

Digestive system

The digestive system of arthropods is divided into three distinct regions, the stomodeum, the mesodeum, and the proctodeum. Stomodeus and proctodeum are the regions located at the anterior and posterior end, respectively; they are covered with cuticle that is renewed every time the animal moults. The middle part of the digestive tract, the mesodeum, derives from the endoderm (second blastodermal sheet) and is the one that produces digestive secretions and where most of the absorption of nutrients takes place; it frequently presents derivations or lateral caecums that enlarge its surface.

Breathing

Many arthropods are too small to have or need respiratory organs. Aquatic arthropods usually have gills, internally more vascularized appendages than other organs. They are found in crustaceans, as specializations of the dorsal branch of the thoracic appendages, and in the same way in kyphosurans or eurypterids or the first fossil scorpions. Secondary gills (derived from tracheae) are also found in the aquatic larvae of some insects, such as mayflies.

As is general in animals, members of the aerial life group breathe through internalized organs, which in arthropods can be of two types:

- Tracheas: Insects, some arcnid orders, miriapods and humid cochinillas (crustaceans adapted to earthly life) present a network of ducts that communicate with the outside by holes called spectacles, often equipped with valve openings that regulate their diameter. The cuticle in these structures is very thin and permeable, which in any case occurs when the mute arrives. In some cases there is active ventilation, with cyclic movements of inspiration and expiration.

- Pulmons in book: They present a very folded internal structure, which multiplies the surface by which the gas exchange is made, and they open to the outside by own and independent openings. There are lungs in book in several arcnid orders, including spiders and scorpions.

Circulation

The circulatory system of arthropods is open, that is, there is no closed circuit of vessels through which a differentiated liquid circulates, which could properly be called blood. What exists is a specialized vessel that runs longitudinally through a large part of the body called the dorsal heart. When this organ contracts, it moves the internal body fluid: the hemolymph, which it receives from open posterior vessels and pushes forward through equally open vessels (separated by valves). The section of the vessel that is connected to the brain is called the aorta, in which it directly irrigates the cerebral cavity and the organs close to it, and then returns to the network of vessels and reaches the dorsal heart again. Hemolymph reaches the extremities through muscular pumps which, with the help of muscular contractions, act as "auxiliary hearts" allowing the circulatory fluid to reach that area of the body.

The network of vessels is always poorly developed, except in the gills of aquatic arthropods. There are no specialized blood cells for oxygen transport, although, as in all animals, there are amebocytes (amoeboid cells) with functions of cellular immunity and hemostasis (coagulation and healing). Yes, there may be respiratory pigments, but dissolved in the hemolymph.

Excretion

Crustaceans have antennal and maxillary glands for excretion, at the base of these appendages. Arachnids usually have coxal glands, which open at the base of the locomotor legs. In insects and myriapods, characteristic tubular organs appear, called Malpighian tubes or ducts, which open between the midgut and hindgut (proctodeum); their products add to the composition of the feces.

Terrestrial arthropods are usually uricotelic, that is, they do not produce ammonia or urea for nitrogenous excretion, but uric acid or, sometimes, guanine.

In arthropods, excretion by accumulation is common, as an alternative or complement to excretion by secretion. In this case, the excretion products accumulate in nephrocytes, pericardial cells or directly in the cuticle. The accumulation is usually of urates or guanine, very poorly soluble nitrogenous bases that form solid deposits. In the latter case, the seedlings serve the added function of getting rid of these excreta.

Nervous system

As befits protostomes, the nervous system develops on the ventral side of the body, and as befits metameric animals, its organization is segmental. A pair of ganglia appears in each segment, positioned more or less ventrolaterally, with the two ganglia of a pair soldered or joined by a transverse commissure and those of consecutive pairs joined by connective nerves.

Central Nervous System

In arthropods it is an anelidian-type organ, therefore, it has a structure primarily in the form of a rope ladder, that is, two longitudinal nerve cords that run through the ventral part of the body, with a pair of ganglia per metamere attached transversely by commissures; however, ganglion concentration processes occur due to the formation of tagmata.

Brain or sincere brain

Normally it is formed by three pairs of associated ganglia, corresponding to the procephalon. Three regions can be distinguished:

- Protoceedings: It is the result of the merger between the odd node of the arquicerebro, dependent on the acronym, and the pair of prosocerebro nodes; it is preoral. Protocerebro has structures related to composite eyes, ocelos and endocrine system:

- Prefrontal lobes: It is a wide region of the middle area of protocerebro where different groups of neurons constitute the pairs intercerrebralis; they are related to the ocelos and the endocrine complex. It also differentiates the central body and the pedunculated or fungiform bodies. These two centers are of association, they are very developed in social insects. They will govern in them the conduct of the colony and the gregarism of it.

- Optical lobes: Inerve the composite eyes, and in them lies the vision. They are very developed in animals with complex eyes such as hexapotes or crustaceans. Three centres differ:

- External lamina

- External index

- Internal regulation

- These are related to each other by quiasmas.

- Deutocerebro: Result of the merger of a couple of nodes; preoral. From the deutocerebro there are nerves that inerve the first pair of crustacean antennas and the antennas of hexapotes and miriapotes. In those nerves, two branches, the motor and the sensitivity need to be differentiated. In addition, there are groups of neurons in which association centers reside with olfactory and enjoyable function. These centres are also presented in the tritocerebro. The cherishes lack deutocerebro; some authors think it is atrophy, while others believe they have never had it.

- Tritocerebro: Result of the merger of a couple of nodes; in origin it is postoral. The tritocerebro inervates the second pair of crustacean antennas, and in hexapodes and miriápodes, the intercalar or premandibular segment, lacking appendices. In the cherries it inerates the cherries. From it there are nerves that relate it to the sympathetic or vegetative nervous system (in the case of hexapotes, with the so-called frontal node). In addition to the tritocerebro part a periesophageal constituency that binds to the first pair of ganglions of the ventral ganglion nerve chain, and a subsophageal comisura that binds the two tritocerebral ganglias together.

In the protocerebrum and deutocerebrum, commissures and connectives are not differentiated. The tritocerebro is formed by a pair of ganglia that join the previous ones in the so-called tritocephalic heads, losing the connectives, while in the deutocephalic heads, it remains independent, conserving the connectives with the deutocerebrum. This occurs in some crustaceans such as branchiopods or cephalocarids. In all cases, the commissure is differentiated, which is subesophageal.

Inside the head capsule, the brain is upright; the protocerebrum and the deutocerebrum are located upwards, and the tritocerebrum is inferior and goes backwards.

Ventral ganglionic nerve chain

It is made up of a pair of ganglia per metamer that initially have connectives and commissures. In primitive groups, the ganglia of each pair of segments appear dissociated, and the structure resembles a rope ladder. The degrees of concentration and shortening are due to the suppression of the commissures and connectives respectively.

Highlight the subesophageal ganglion; in hexapods it is the result of the fusion of three pairs of ventral ganglia corresponding to metameres IV, V and VI and innervates the mouthparts (the mandibles and the two pairs of maxillae) and is therefore called gnathocerebrum; in decapods, there are six associated ganglia (since the three ganglia of maxillipeds are included.

Sympathetic or vegetative nervous system

Sensory and motor neurons that form ganglia and are located on the walls of the stomodeum. This system is related to the central nervous system and the endocrine system. There are two parts to the sympathetic nervous system.

- Stematogastric sympathetic system: It is always present. It is diversely formed by odd ganglia, united with each other by recurrent nerves. It has as function the regulation of the swallowing processes and the peristal movements of the digestive tract. It also regulates the heartbeat.

- terminal or flow friendly system: It may or may not be present. It's also odd, and it's tied to the last ganglia of the ventral ganglion nerve chain. Its function is to inerve proctodeo, act in reproductive processes, egg laying and sperm transfer, and also regulates the beats of the stigmas of the last segments of the abdomen.

Senses

Most arthropods are endowed with eyes, of which there are several different models.

- The simple eyes are spheroidal cavities with a simple retina and covered frontally by a transparent cornea, Its optical performance is very limited, with the exception of the great eyes of some spiders families, such as leaps.

- The composite eyes are composed of multiple equivalent elements called omatides that are radially arranged, so that each one points in a different direction and among all they cover a more or less wide angle of view. Each omatide contains several sensitive, retinal cells, behind transparent optical elements, fulfilling the function that the cornea and the crystalline play in the eyes of vertebrates. There are also cells that wrap the omatide by sealing it in front of the light. Not all groups have composite eyes, which are absent, for example, in the arcnides.

The vision of many arthropods has advantages that are often lacking in vertebrates, such as the ability to see in an extended spectrum that includes the near ultraviolet, or to distinguish the direction of polarization of light. Color vision is almost always present and can be very rich; The crustacean Squilla mantis presents thirteen different pigments with different sensitivity to color, which contrasts with the poor trichromatic system (of three pigments) of most primates, including our species.

Distributed throughout the body, sensilla can be found, which are receptors sensitive to chemical stimuli, such as those of taste or smell, and tactile receptors, associated with antennae and palps and also with tactile setae, hairs that are associated with a sensitive cell. Some insects have a sense of hearing, which is revealed by the existence of auditory signals for intraspecific communication, such as crickets. Many are sensitive to ground vibrations, by which they detect the presence of prey or predators; others, like flies, have trichobothria capable of perceiving minimal changes in environmental pressure.

Arthropods are often endowed with simple but effective position sensors that help them maintain position and balance, like the chordotonal organs that a diptera has on the halteres.

Playback

In sexual reproduction, the females, after being fertilized by the males, lay eggs. Development, from the egg, can be direct or indirect.

- In direct development an individual is born similar to the adult, although, as it is logical, smaller.

- In indirect development a larva is born that involves a series of profound changes called metamorphosis.

There are frequent cases of parthenogenesis (the female produces a zygote without having been fertilized), especially in crustaceans and insects. There are also cases of reproduction by embryogenesis, which is one of the types of fragmentation where the larvae, young or embryonic stages divide into new individuals.

There are also cases of hermaphroditism that appear mainly in parasitic or sessile species.

Phylogeny

For many decades, the phylogenetic relationships of coelomates were based on Cuvier's conception of the articulates (Articulata), a clade consisting of annelids and arthropods. Numerous modern morphological analyzes based on cladistic principles have corroborated the existence of the Articulata clade, eg Brusca & Brusca, Nielsen or Nielsen et al., among others.

However, various cladistic analyzes such as the pooled data analysis by Zrzavý et al (1998) and others have concluded that annelids and arthropods are not directly related. The presence of metamerization in annelids and arthropods must be considered a case of evolutionary convergence. Rather, these studies proposed the clade Ecdysozoa in which arthropods show close phylogenetic relationships with pseudocoelomate groups, such as nematodes, nematomorphs, priapulids, and quinorhynches, by the shared presence of a chitinous cuticle and a molting process (ecdysis) of the cuticle. same. Ecdysozoa, as currently defined, includes members of three putative subclades: Nematoida (Nematoda and Nematomorpha), Scalidophora (Priapulida, Loricifera, and Kinorhyncha), and Panarthropoda (Arthropoda, Onychophora, and Tardigrada).

The phylogeny of arthropods has been highly controversial, with a dispute between supporters of monophylletism and those of polyphylletism. Snodgrass and Swan They have defended monophylletism, although the first considers arthropods divided into arachnids + jawed, and the second interprets them divided into schizoramous and atelocerate. Tiegs & Manton defended diphylletism, with arthropods divided into schizoramous + uniramous and onychophorans as a sister group to myriapods + hexapods. Subsequently, Manton and Anderson supported the polyphylletism of the group (see Uniramia).

With the appearance of the first studies based on molecular data and combined analyzes of morphological and molecular data, it seems that the old controversy about monophyly and polyphyly has been overcome, since all of them corroborate that arthropods are a monophyletic group in the which also include onychophorans and tardigrades (the clade has been called panarthropods); most also propose the existence of the Mandibulata clade that brings together the subphyla Hexapoda, Crustacea and Myriapoda. It had primarily been proposed that hexapods might be related to crustaceans or myriapods, however the hypothesis that they would be related to myriapods has been largely discounted, due to various molecular analyzes and fossil evidence suggesting that crustaceans are closely with the hexapods and that in fact they are a paraphyletic group of the latter, therefore the phylogenetic relationships of the classes of arthropods would be as follows:

| Arthropoda |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Taxonomy

The arthropod phylum (Arthropoda) is divided into four subphyla.

- The subfilo will unite (Uniramia) comprises five classes: diplópodos (Diplopoda), milpiés; chilopodes (Chilopoda), ciempiés; paurópodos (Pauropoda), small animals without eyes and cylindrical body that carry 9 or 10 pairs of legs; symphiles (Symphyla), the ciempiés of garden.

- The crustacean subfilo (Crustacea), which is mostly marine (although not infrequent on the ground) abounds in fresh water and includes animals such as lobsters, kettles or shrimps, and crabs.

- The cherished subfilo (Chelicerata) is characterized by presenting the first pair of modified appendices in queliceros and due to lack of antennas; it consists of three classes: Arachnida (Arachnida), spiders, scorpions and mites; merostomados (Merostomata), the horseshoe crabs or cacerolas; and picnogonides (Py)

- Trilobitomorphic extinct subfilo (Trilobitomorpha) included trilobites.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Phylogenetic tree of arthropods and related groups

According to another classificatory proposal, the phylum is divided into five subphyla:

- Subfil Trilobitomorpha

- Subfil Cheliceriformes

- Crustacea subfil

- Subfilo Hexapoda

- Subfilo Myriapoda

Contenido relacionado

Theobromine

Struthio camelus

Lophotrochozoa