Aria

An aria, from the Italian aria ("air"), is a piece of music created to be sung by a solo voice without a chorus, usually with orchestral accompaniment and as part of an opera or a zarzuela. Formerly, it was any expressive melody performed frequently, although not always, by a singer. An aria is similar to the world of suites as it is a piece of a cantabile character, slow-moving, ternary or binary, and profusely ornamented. In any case, it is a theatrical or musical composition from the late Renaissance, composed to be performed by a single performer.

During the 17th century, at the time of Baroque opera, the aria was written in ternary form (A-B-A), which was known as the aria da capo (aria from the beginning) due to the repetition of the first part at the end of the aria. The aria then “invaded” the operatic repertoire with numerous variants (aria cantabile, aria agitata, aria di bravura, among others). In the mid-19th century, operas became a succession of arias, reducing the space available for recitatives.

An aria is now often used for plays or, generally, opera openings.

At the opera

Aryan form in French and Italian opera of the late 17th century

In the context of stage works and concert works, arias evolved from simple melodies to structured forms. In such works, the structured, melodic, sung aria differed from the more speech-like recitative (speaking). In general, the latter tended to carry the story line, while the former carried a more emotional charge and became an opportunity for the singers to showcase their vocal talents.

The aria typically evolved in one of two ways. The binary form arias consisted of two sections (A–B); arias in ternary form (A – B – A) were known as arias da capo (literally 'from the head', that is, with the opening section repeated, often in a highly ornate manner. In the aria da capo, episode B would normally be in a different key: the dominant or relative major key Other variants of these forms are found in late-century French operas XVII like those of Jean-Baptiste Lully, who dominated the French Baroque period.In his works the vocal solos (referred to by the French term airs) often have extended binary (ABB) form, or sometimes rondo form (ABACA), a form that is analogous to the instrumental rondo.

In the Italian school of composers of the late XVII century and early XVIII, the da capo form of the aria gradually became associated with the ritornello (literally 'little return'), a recurring instrumental episode that it was interspersed with elements of the aria and eventually provided, in early operas, the opportunity for dancing or the entrance of characters. This version of the aria form with ritornello became a dominant feature of European opera throughout the century. XVIII. Some writers think it is the origin of the instrumental forms of the concerto and sonata form. The ritornelli became essential to the structure of the aria: "while words determine the character of a melody, ritornello instruments often decide." in what terms it will be presented".

18th century

By the early 18th century, composers such as Alessandro Scarlatti had established the aria form, and especially its version da capo with ritornelli, as a key element of opera seria. “It offered balance and continuity, and yet allowed room for contrast. [...] The very regularity of their conventional characteristics allowed deviations from the normal to be exploited to revealing effect." In the early years of the century, arias in the Italian style began to prevail in French opera, eventually giving rise to the French genus of ariette, usually in a relatively simple ternary form.

Types of operatic aria became known by a variety of terms according to their character, for example, speaking aria ('speaking style', narrative in nature), aria di bravura (usually given to a heroine), aria buffa (comic type aria, usually given to a bass or bass-baritone), and so on.

M. F. Robinson describes the standard aria in opera seria in the period from 1720 to 1760 as follows:

- The first part normally began with an orchestral ritornello after which the singer entered and sang entirely the letter of the first verse. At the end of this first vocal paragraph, the music, if it was in a greater tone as it used to be, had been modified to the dominant one. The orchestra then played a second ritornello, usually shorter than the first. The singer went back in and sang the same words for the second time. The music of this second paragraph was often a little more elaborate than that of the first. There were more repetitions of words and perhaps more flourishing vocalizations. The key returned to the tonic for the final vocal cadence, after which the orchestra closed the section with a final ritornello.

The nature and assignment of arias to different roles in opera seria was highly formalized. According to the playwright and librettist Carlo Goldoni, in his autobiography:

- The three main characters of the drama should sing five arias each; two in the first act, two in the second and one in the third. The second actress and the second soprano can only have three, and the lower characters must conform to one aria each, or two maximum. The author of the words must [...] take care that two pathetic arias [i.e., melancholy] do not happen. It must distribute with the same caution the arias of bravura, the arias of action, the arias inferior and the minuetos and rumdos. It must, above all, avoid giving passionate arias, bravura arias or rumdos, to lower characters.

In contrast, arias in the opera buffa (comic opera) often had a character specific to the nature of the character being portrayed (for example, the cheeky servant girl or the suitor or tutor irascible old man).

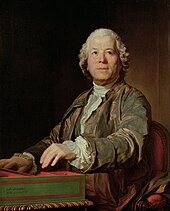

By the end of the century it became clear that these formats were becoming fossilized. Christoph Willibald Gluck thought that both opera buffa and opera seria had strayed too far from what opera should really be, and seemed unnatural. The jokes of the opera buffa were threadbare and the repetition of the same characters made them seem like nothing more than stereotypes. In opera seria, the singing was devoted to superficial effects and the content was uninteresting and stale. As in opera buffa, the singers were often masters of stage and music, embellishing the vocal lines in such a florid manner that the audience could no longer recognize the original melody. Gluck wanted to return opera to its origins, focusing on drama and human passions and making words and music equally important. The effects of these Gluckist reforms were seen not only in his own operas but in Mozart's later works; the arias now expressed much more the individual emotions of the characters and were more firmly anchored and advanced in the plot. Richard Wagner would praise Gluck's innovations in his 1850 essay Opera and Drama: "The musical composer rebelled against the obstinacy of the singer" instead of "unfolding the purely sensual contents of the Aria at its most high"; Gluck sought to "shackle Caprice's performance of that Aria, striving for himself to give the melody a [...] expression that responds to the underlying text". This attitude was the basis for the possible deconstruction of the aria from Wagner in his concept of total work of art (Gesamtkunstwerk).

19th century

Despite Gluck's ideals and the tendency to arrange libretti so that arias played a more organic role in the drama rather than simply interrupting its flow, in turn-of-the-century operas XIX (for example, those of Gioachino Rossini and Gaetano Donizetti), arias di bravura remained central attractions and continued to play an important role in grand opera and in Italian opera during the XIX century.

A preferred aria form in the first half of the XIX century in Italian opera was the cabaletta, in which a song-like cantabile section is followed by a livelier section, the cabaletta proper, repeated in whole or in part. Normally such arias would be preceded by a recitative, and the entire sequence would be called a scene. There may also be opportunities for orchestra or choir participation. An example is Casta Diva from Vincenzo Bellini's opera Norma.

Around 1850, aria forms in Italian opera began to show more variety: many of Giuseppe Verdi's operas offer extended narrative arias for leading roles that allow for, in their scope, intensification of drama and characterization. Examples include Rigoletto's sentence to the court, "Cortigiani, vil razza dannata!" (1851).

Later in the century, Wagner's operas after 1850 were fully composed, with fewer elements easily identifiable as stand-alone arias; while the Italian genre of verismo opera also sought to integrate airy elements while still allowing some & #39;pieces of show'.

Concert Arias

Concert arias, which are not part of any larger work (or are sometimes written to replace or insert arias into their own operas or operas by other composers) were written by composers to provide the opportunity for vocal display for concert singers; examples are Ah perfido!, op. 65, by Beethoven, and several concert arias by Mozart, including Conservati fedele.

Instrumental music

The term "aria" was used frequently in the 17th and XVIII for instrumental music used for dance or variation, and was inspired by vocal music. For example, Johan Sebastian Bach's Goldberg Variations were titled in his 1741 publication "Clavier Ubung bestehend in einer ARIA mit verschiedenen Verænderungen" ('Keyboard exercise, consisting of an ARIA with several variations'), and composed when Bach was cantor in the church of Saint Thomas of Leipzig.

The word is sometimes used in contemporary music as a title for instrumental pieces, for example Robin Holloway's 1980 "Aria" for chamber ensemble or Harrison Birtwistle's marching band piece "Grimethorpe Aria" » (1973).

Contenido relacionado

Golden Raspberry Awards

Overture 1812

Viña del Mar International Song Festival