Architeuthis

Architeuthis is a genus of cephalopods of the order Teuthida commonly known as giant squids. Up to eight species have been proposed, although some scientific groups argue that only one exists.

They are deep-dive marine animals that reach extraordinary dimensions; recent estimates suggest a maximum of 10 m for males and up to 13 m for females. There has been speculation about the existence of specimens of much more than twenty meters and half a ton in weight, although this has not been confirmed. One One of the largest specimens was a female almost 18 meters long, whose corpse was washed up on a New Zealand beach in 1887. There is also mention of another specimen accidentally captured in 1933, in New Zealand waters, 21 meters long. long and 275 kg in weight.

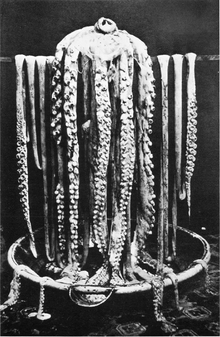

The tentacles, located on the head, measure from 2.5 to 6 times the length of the mantle or visceral sac, and make up most of the body length. On September 30, 2005, researchers from the National Science Museum of Japan and the Ogasawara Whale Watchers' Association obtained images of a giant squid in its natural habitat. 556 photos were obtained in 2004. And the same team filmed a squid giant for the first time on December 4, 2006. The first video images of a live specimen in the wild were taken in the summer of 2012 by a joint Discovery Channel and NHK television team and premiered in its entirety on January 13, 2013 for Japan and on the 27th for the US.

Morphology and anatomy

Despite its enormous size, the giant squid is not particularly heavy when compared to its main predator, the sperm whale, because its prominent length is mainly due to its eight arms and two tentacles. The weights of the captured specimens have been measured in hundreds of kilograms. Postlarval juveniles have been discovered in surface waters off New Zealand. There are plans to capture these young specimens in order to be studied.

Very little is known about its reproductive cycle. The male has a prehensile spermatophore or reservoir tube; which acts as a penis, 9 dm long, extending from within the mantle, and apparently used to inject sperm into the female's reservoir (located on one arm). Although the means by which the sperm is transferred to the egg mass is the subject of much debate, a capture in Tasmania of a female specimen with a small tendril subsidiary attached to the base of each of its eight arms could be vital to solving the question. This species loses the hectocotyls used in reproduction as in many other cephalopods.

The arms are equipped with hundreds of suction cups in two rows lengthwise, each mounted on an individual base, and fitted around its circumference with a toothed ring that helps it capture its prey by gripping it firmly between the arms. suction and drilling. The size of the suckers varies from 2 to 5 cm in diameter, and it is common to find circular scars near the mouth of sperm whales that hunt these animals. Another known predator of the giant squid is the sleepy shark Somniosus pacificus, in the Southern Ocean, but it is not known whether these sharks actively hunt them, or are simply scavengers of squid carcasses.

One of the most unusual aspects of this species (as well as some other large squid species) is its tendency to maintain low ammonium densities relative to seawater and thus maintain neutral buoyancy in its natural environment. (the water column), since they lack a gas-filled swim bladder as teleost fish use for that function, they use the ammonium chloride that is there for their muscle tissue.

Like all cephalopods, giant squids have special statocyst organs to sense their orientation and movement in the water. The age of a specimen can be determined by means of "growth rings" in the statoliths of the statocyst, analogous to determining the age of a tree by counting its rings, from which it can be deduced that males grow about 2.6 mm per day and females 4.68 mm.

Vision

With a diameter of up to 25 cm, the Architeuthis dux is considered the animal with the largest eyes, although it is believed that the colossal squid could have even larger eyes. These eyes lack a horny membrane (oegopsid eyes), just like the other species of squids and flying squids, unlike true squids that have it.

Cephalopods are distinguished from other invertebrates by having a complicated visual system. Both the cephalopod and vertebrate visual systems are an example of convergent evolution. This means that both groups of animals are similar, but their ability to see developed separately in each group. In fact, if we compare the eyes of a squid with ours, we find notable differences in terms of their anatomy. Both squids and humans have simple eyes, with pupils, irises, and a retina.

Size

The growth rate of a giant squid is extraordinarily fast. It is the animal with the fastest growth rate, which is why in a few years they have that enormous size. Its overall length, particularly, has often been exaggerated. There are records of specimens measuring more than 20 m in length, but it has never been scientifically documented. Such lengths may be confused by the extremely large extensions of its two rubber band-like feeding tentacles. The 1887 specimen actually measured less than 13 meters, the rest is a consequence of this post mortem stretching.

The giant squid reaches considerable sizes, with mantle length (LM) records greater than 4.5 m, total length of most records from 6 to 13 m. This genus presents a pronounced sexual dimorphism. The maximum weight is estimated at 312 kg for females, and 178 kg for males. Males have a shorter lifespan than females and mature sexually earlier, it is estimated that males live around one year and females twice or twice as long. triple the years

Food

Although the giant squid has eight arms, it is the two longest tentacles that are used to capture prey, and can reach 12 m in length. Each tentacle is equipped with suckers, which present a kind of ring with teeth. While they suck, their teeth dig into the victim's skin, thus providing greater security when stalking their prey. The squid's mouth closely resembles a parrot's beak. The tongue is equipped with an organ called the radula, in charge of chopping up the prey before it passes into the esophagus so that it can be digested.

In feeding studies, a high percentage of cod and other fish have been found in their stomachs. The latest necropsies also reveal remains of small crustaceans. On the other hand, squids are the favorite snack of sperm whales, which descend to the abyssal zone (more than 1,000 m) to get their meat, thus giving rise to titanic underwater fights. They are also eaten by deep-sea bony and cartilaginous fish and seabirds such as albatross, Diomedea exulans.

Playback

To determine the age of a squid, the ear bones are studied -the statoliths-, the organs of balance, which have a series of concentric rings like those found in tree trunks; all you have to do is count that number of rings to determine the age of a squid. The maximum age it can reach is 3 years.

Like many fish, squid have many limitations in reproducing. If things go wrong one year, either due to poor health, bad environmental conditions, etc., in the following years they will have many problems to reproduce. Squid make up for this by laying large numbers of eggs.

By comparing the reproductive system of the giant squid with that of other squids, it is considered probable that clutches consisted of small eggs surrounded by a gelatinous mass, left adrift in the water column. The oocytes are small, oval, 1.2-2.5 mm in greatest diameter. Potential fecundities were estimated between 1 million and 12 million oocytes. Males produce spermatophores 80-200 mm in length and females lack spermatheca. It is unknown how the insemination and subsequent fertilization of the oocytes would occur. Spermatangia (devaginated spermatophores) were found implanted in various body parts of females and males (mantle, head, eyes, arms, tentacles, siphonal cavity, and male end organ). It was suggested that spawning would be intermittent and prolonged. The paralarvae are epipelagic.

Giant squids, both Architeuthis dux and Taningea danae, are characterized by having a reproductive system quite different from other cephalopods. For this reason they have a copulatory organ or penis, which can reach 85 cm in length in Taningea and 78 in Architeuthis.

In the case of the Taningea, it not only has a reproductive organ, easily visible, because it is externalized, having a length as long as the arms. It also has another with similar characteristics, although somewhat smaller (1/5 part) within the mantle.

Species

The taxonomy of the giant squid, as with many genera of cephalopods, has not been fully resolved. There is quite a bit of controversy although some scientists have proposed these nine species:

- Architeuthis dux - giant Atlantic squid.

- Architeuthis hartingii

- Architeuthis japonica

- Architeuthis kirkii

- Architeuthis martensi

- Architeuthis physeteris

- Architeuthis princeps

- Architeuthis sanctipauli - South giant squid.

- Architeuthis stockii

It is likely that they are not all different species. No genetic or physical basis is available for distinguishing between the species names that have been proposed, based on the location of the specimen's capture, to describe them. The peculiarity of the observations of specimens and the extreme difficulty of observing them alive, of following their movements, or of studying their habits makes a complete study difficult.

In the 1984 FAO Species Catalog of the Cephalopods of the World, C.F.E. Rope, M.J. Sweeney and C.F. Nauen wrote:

Many species have been named in a single genus of the Architeuthidae family, but they would be inadequately described and poorly understood, so the systematic group remains confused.

Kir Nazimovich Nesis (1982, 1987) considers only three species to be valid.

In 1991, Frederick Aldrich of the Memorial University of Newfoundland wrote:

I reject the concept of 20 separate species, and until this matter is resolved, I choose to place them all in synonym with Architeuthis dux Steenstrup.

In a letter to Richard Ellis dated June 18, 1996, Martina Roeleveld of the South African Museum wrote:

So far, I haven't seen anything suggesting there could be more than one kind of "Architeuthis".

In Cephalopods: A World Guide (2000), Mark Norman wrote the following:

The number of species of giant squids is not known, although the general consensus among researchers is that at least there are three species, one of the Atlantic ocean (Architeuthis dux), one of the Antarctic Ocean (A. sanctipauli) and at least one in the North Pacific Ocean (A. martensi).

Distribution

They are found in all oceans although it is rare to find them in tropical and polar waters. They have been found in the North Atlantic, Scotland, Ireland, South Africa, New Zealand and Spain, specifically in the Carrandi Caladero, between 18 and 30 miles (vertical from Colunga) and in the Canary Islands. Cepesma has 21 giant squids of different species. The Architeuthis on display range from 6 m to 13 m in length. The first specimen is an immature female of 1.5 years and 147 kg. The second specimen weighs 140 kg and has 6.5 m long tentacles. There are also specimens of 120, 114, 107 kg, among the largest.

Displacement

The displacement of the squid is carried out by means of its siphon, something similar to a “jet propulsion” system. The two small fins on their mantle serve as stabilizers. Due to their proportions, giant squids out of the water are, indisputably, really heavy, however in the water they have neutral buoyancy. This is due to a high concentration of ammonium ions in its muscles. Ammonium ions are lighter than seawater, so the animal can maintain its level in the water without the need for high energy expenditure by constantly swimming. Although ammonium is toxic to most animals, and must be disposed of in the form of urea, or uric acid, squid in some as yet unknown way accumulate this toxic substance without being harmed. For this reason, the meat of this cephalopod is toxic for us, while it is not for the sperm whale.

History and myth

Aristotle, who lived in the IV century B.C. C., described a large squid, which he named teuthus, distinguishing it from the smaller squid, the teuthis. He mentions that “of the squids the teuthus is much larger than the teuthis; among the Teuthi [plural of Teuthus] specimens as large as five fathoms have been found.”

Pliny the Elder, who lived in the I century d. C., also described a gigantic squid in the Naturalis Historia of him, with a head "as big as a barrel", arms 9.1 m long, and a body mass of 320 kg.

Stories about giant squids have been common among sailors since ancient times. The existence of these stories go back to the Norwegian legend of the kraken. In 1755 that word was used to describe a large sea serpent that swam near a ship off the coast of Norway.

Japetus Steenstrup produced a series of papers on giant squid in the 1850s. He was the one who coined the term "Architeuthis," using it to define giant squids, in a paper in 1857. A part of a giant squid was saved by the French ship Alecton in 1861, this finding allowed a greater knowledge of the species/genus by the scientific community. Between 1870 and 1880, large numbers of squid were found stranded on the shores of Newfoundland. For example, a specimen from Thimble Tickle Bay in Newfoundland, found on November 2, 1878, was 6.1 m long. One of its tentacles was 10.7 m long and was estimated to have a weight of 2.2 t. In 1873, a squid "attacked" to a minister and a child in a dory on Bell Island, Newfoundland. Giant squids have also been found stranded in New Zealand in the late 19th century.

Although strandings continue to occur sporadically around the world, they have never occurred as frequently as those that occurred in Newfoundland and New Zealand during the last century XIX. It is not known why some giant squids are stranded on the beaches, but it may be due to the difference in depth, the cold water where the squid lives is temporarily altered. Many scientists who have studied squid mass strandings believe they are cyclical and predictable. The length of time between strandings is not known, but specialist Frederick Architeuthis Aldrich proposed that it should be about 90 years. Aldrich uses this value to correctly explain a relatively small stranding that occurred between 1964 and 1966.

In 2004, a giant squid, later named "Archie," was caught off the coast of the Falkland Islands by a trawler. It measured 8.62 m long and was transferred to the Natural History Museum in London to be studied and preserved. It was displayed in a museum exhibit on March 1, 2006. Finds of a complete specimen are very rare, as most specimens are in poor condition after having washed up on beaches when dead or having been recovered from the stomach of dead sperm whales.

Researchers went through a painstaking process to preserve the body. It was transported frozen to England aboard a trawler and then thawed, a process that took about four days. The main difficulty with the thaw is that the thick mantle took much longer than the tentacles. To prevent the tentacles from rotting, the scientists covered them with ice packs, and the mantle was bathed in water. Then the squid was injected with a formol-saline solution to prevent rotting. The creature is now in a 9 m long display case in the Darwin Center in the aforementioned Museum of Natural History.

In December 2005, the Melbourne Aquarium in Australia paid AUD$100,000 (about £47,000 GBP or US$90,000) for the intact body of a giant squid, preserved in a large block of ice, which had been caught by fishermen off the coast of New Zealand's South Island that year.

The first images of a live giant squid were recently obtained. It was a Japanese team from the National Museum of Science in Tokyo, who followed a group of sperm whales, the only known predator of the giant squid, to their feeding ground. In the depths of the Ogasawara Islands in the Pacific Ocean, the team repeatedly suspended a rope to which they attached a common squid and shrimp bait (jig), along with a camera. On September 30, 2005, the news appeared in several world-renowned media: "The adult giant squid finally attacked one of the baits, which allowed more than 550 photos of the animal to be taken in its struggle to free itself" (although the photographs were made the previous year). The squid lost a 5.5 m long tentacle in its struggle, which allowed us to infer a total length between seven and eight meters.

In early December 2006, the same team led by Tsunemi Kubodera once again managed to capture and film a giant squid of the species Architeuthis dux in its natural environment and on the surface (it had never been seen before). achieved). On December 4, 2006, off the Ogasawara Islands, a young female measuring 3.5 m in length and weighing 50 kg was captured (a small size compared to the 21 m and 275 kg that have reached reach some individuals of this species). Common squid bait was used at the end of a rope, and a camera was added to it. The animal was able to be brought to the surface for investigation, but it died.

The number of known giant squid specimens was established at around 600 in 2004, and new specimens continue to be recorded each year. The search for live Architeuthis involves the capture of young individuals, including some in larval stage. Giant squid larvae are very similar to those of Nototodarus and Moroteuthis .

At the end of 2016, a 105-kilo calf was photographed alive on the coast of Galicia, which later died.

Giant Squids in Culture

The giant squid's elusiveness and terrifying appearance are images that have become firmly established in the human mind. The image that humans have of the giant squid has evolved since the first legends about the kraken appeared until the appearance of books such as Moby-Dick, Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea or in the novel The Red One, by Berhard Kegel. It also appears in the book Beast (1991) by the writer Peter Benchley, which was adapted for a telefilm by the director Jeff Blackner.

In particular, a very recurring image has been that of a giant squid catching a sperm whale with its tentacles, when in reality, the squid is usually the sperm whale's prey.

Contenido relacionado

Joint (anatomy)

Psittacidae

Tuberous sclerosis