Aramaic languages

The Aramaic languages (from Hebrew אֲרָמִית / arāmît; in Arabic: ɐɐͪvocavoc / Ārāmāyâ) “from the land of Aram”) make up a branch of Semitic languages with a history of at least 3,000 years, a branch that involves a diversity recognized by its presence in the Bible, and possible language of Jesus of Nazareth.

Old Aramaic was the original language of large sections of some books of the Bible, such as the Book of Daniel and the Book of Ezra, as well as the primary language of the Talmud, the Bahir, and the Zohar. Although there is evidence that it was spoken in Judea in the I century, it is still today the main language of some small non-U.S. Arabic speakers of the Near East.

The Aramaic group belongs to the family of Semitic languages, like Arabic and Hebrew, which in turn are part of the Afroasiatic macrofamily, and to the group of Northwest Semitic languages that includes the Canaanite languages.

Historical, social and cultural aspects

Geographic distribution

During the XII century B.C. C., the Aramaeans -primitive speakers of this language- began to settle in a territory that corresponds to present-day Syria, Armenia and eastern Turkey. From there they expanded into a wider territory, stretching from the eastern shore of the Mediterranean to the eastern shore of the Tigris. The most widely spoken common language in the Middle East today is Arabic, but Aramaic still holds importance as a liturgical and literary language among Jews, Mandaeans, and some Christians. Additionally, the turbulence experienced during the last two centuries in this region, has dispersed Aramaic speakers throughout the world.

Varieties of Aramaic

Strictly speaking, Aramaic is not a single homogeneous language, but a group of well-differentiated but related languages. The modern varieties are fragmentations resulting from the long history of Aramaic (reflected in its extensive literature and in its use by different communities, which form separate communities of different religions). The diversity of the Aramaic languages is such that there are varieties that are mutually unintelligible, while others have some degree of mutual intelligibility. Some are even known by a different name, such as Syriac, a dialect of Aramaic spoken by Christian communities in the east.

Aramaic dialects are classified both historically and geographically. By historical periods, a distinction is made between the modern Aramaic languages, also known as Neo-Aramaic, those that are restricted to literary use and those that are extinct. With certain exceptions, this logic distinguishes between the old, medium and modern categories. As for modern dialects, the distinction is geographical, so modern dialects are classified into Eastern Aramaic and Western Aramaic, the boundary of which can be delineated roughly on either side of the Euphrates River, or slightly to the west of it. A traditional scheme from contemporary Aramaic is as follows:

- Eastern Neo-Aramaic

- Neoarameo noriental

- Turoyo

- Western Neo-Aramaic

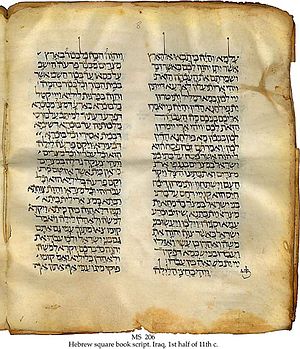

Writing system

The first system used to write Aramaic was based on the Phoenician alphabet. Subsequently, Aramaic developed its distinctive style of writing, which was adopted by the Israelites and other inhabitants of Canaan for their own languages, which is why it is now better known as the Hebrew alphabet. This is the writing system used in Biblical Aramaic.

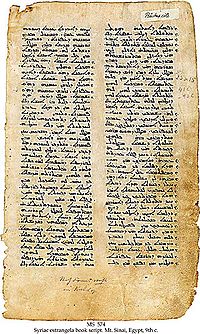

There are other writing systems for Aramaic as well, one developed by Christian communities, a cursive form known as the Syriac alphabet, and another, a modification of the Aramaic alphabet known as the Mandaean alphabet.

In addition to these writing systems, some derivatives of the Aramaic alphabet have been used throughout history by particular groups, such as the Nabataean alphabet at Petra and the Palmyrene alphabet at Palmyra. In modern times, turoyo has sometimes been written with an adapted Latin alphabet.

History

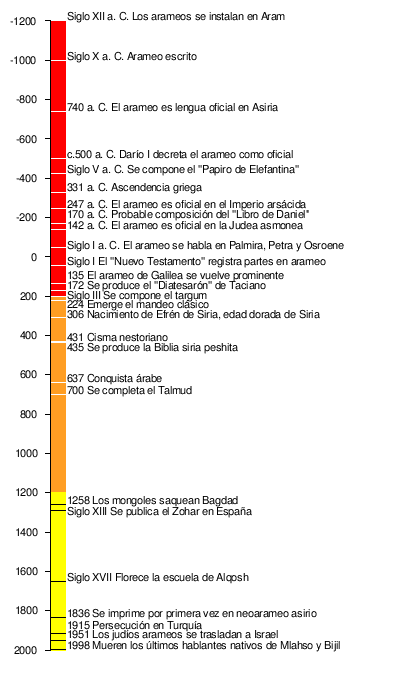

|

The following is a comprehensive history of Aramaic. This is divided into three major periods:

- Ancient Aramaic (1100 B.C.-200 AD), which includes:

- The Biblical Aramaic of the Hebrew Bible.

- The Aramaic of Jesus Christ.

- Aramaic medium (200-1200), including:

- The literary Syriac.

- The Aramaic of the Talmudes, Tarrgumim and Midráshim.

- Modern Aramaic (1200 on), which includes:

- Several modern vernacular forms.

This classification is based on the one used by Klaus Beyer *.

Old Aramaic

This period includes the Aramaic spoken by the Aramaeans from its origin until it became established as the lingua franca of the region. Ancient Aramaic comprises more than thirteen centuries of the language's history. This wide span of time has been chosen in such a way that it covers all the dialects that are currently extinct. The most important point in the history of ancient Aramaic occurs around 500 B.C. C., when it becomes Imperial Aramaic. The different dialects of Aramaic in the region become relevant when Greek replaces Aramaic as the language of power in the region.

Early Old Aramaic

Understands Aramaic from its origin. It was the language spoken in the city-states of Damascus, Hamath, and Arpad. There are many inscriptions that show the earliest use of the language, dating from the X century BCE. C. These inscriptions are mainly diplomatic documents between the Aramaic city-states. The Aramaic script in this period appears to be based on the Phoenician alphabet, and there is uniqueness in the written language. The rule of the Assyrian Empire by Tiglathpileser III in the region of Aram in the mid VIII century BCE. C. led to the establishment of Aramaic as the lingua franca of the Fertile Crescent.

Late Old Aramaic

When Aramaic spread during the 8th century century B.C. C., lost its homogeneity, and different dialects began to emerge in Mesopotamia, Babylonia, the Levant and Egypt, the most widespread being those influenced by Akkadian in Babylonia. In this way they are described in the Second Book of Kings, in which officials of Hezekiah, king of Judea, intend to negotiate with the Assyrian ambassadors in Aramaic, in such a way that the people do not understand. Around 600 B.C. C. Adon, a Canaanite king, writes to the Egyptian pharaoh in Aramaic.

Chaldee was used as the common language of the Babylonian Chaldean dynasty, and was used to describe Biblical Aramaic, which was later written in a later style. This dialect should not be confused with Chaldean Neo-Aramaic.

Imperial Aramaic

Around 500 B.C. C., Darius I established Aramaic as the official language in the western half of the Achaemenid Persian Empire. The local dialect of Eastern Aramaic was already used by Babylonian bureaucrats at that time, so Darius's edict put Aramaic on a solid footing. New Imperial Aramaic was largely standardized, its spelling based more on its historical roots than the pronunciation of any spoken dialect, while the influence of Persian gave it a new clarity, flexibility, and robustness. Imperial Aramaic is also known as official Aramaic or biblical Aramaic. For centuries after the fall of the Achaemenid Empire in 331 B.C. before Alexander the Great, Imperial Aramaic, as established by Darius, remained the dominant language of the region.

The term Achaemenid Aramaic is used to describe the Imperial Aramaic used during the Achaemenid Empire. This period of Aramaic is generally considered to be from Darius I's proclamation around 500 BCE. C. until approximately a century after the fall of the empire in 331 a. Many of the documents attesting to this form of Aramaic come from Egypt, particularly from Elephantine, and the best known of all is Words of Ahiqar, a book of instructive aphorisms very similar to the book of Proverbs (from the Hebrew Bible). The uniformity of Achaemenid Aramaic is such that it is often difficult to determine where a particular fragment of the language was written. Only a careful examination of the text reveals any foreign word borrowed from a local language.

In 2008 a group of thirty Aramaic documents, dating back to the IV century BCE, was published. C., which were found in Bactria. The importance of the find is due to the paucity of material in Achaemenid Aramaic outside of Egypt and the Bible.

Post-Achaemenid Aramaic

The unity of the Aramaic language and literature was not immediately destroyed by Alexander the Great's conquest. Aramaic survived in much the same way as Darius I decreed in the V century BCE. C., until the beginning of the century II d. C. The Seleucids imposed the Greek language as official in the administration of Syria and Mesopotamia from the beginning of their rule, so that it replaced Aramaic as the common language of the region as early as the III. However, Aramaic continued to flourish in Judea, across the Syrian desert, and spread to Arabia and Parthia as an anti-Hellenistic declaration of independence.

Within this category is Hasmonean Aramaic, official in Judea between 142 and 37 BC. C., which influenced the Aramaic of the Qumran texts and was the main language of non-biblical theological texts of the Essene community. The Targum, translation of the Hebrew Bible into Aramaic, was made in this Aramaic. The Hasmonean also appears in quotes in the Mishnah and the Tosefta. Its writing is different from Achaemenid Aramaic, as the spelling emphasizes pronunciation rather than etymological forms.

Babylonian targum is the last post-Achaemenid dialect found in Targum Onchilos and Targum Jonatan, the targums i> officers. The original Hasmonean targum arrived in Babylonia between the II and III and was modified according to the contemporary Babylonian dialect to create the standard language of targums. This combination formed the basis of Babylonian Jewish literature in the following centuries.

The Galilean targum is similar to the Babylonian targum in that it was formed from the combination of the literary Hasmonean and the Galilean dialect, around the II. However, no authority is attached to it, and documentary evidence shows that the text has been corrected to the extent that improvements were needed. Beginning in the 11th century, when the Babylonian targum became normative, the Galilean version She has been greatly influenced by him.

Documentary Babylonian Aramaic is a dialect used since the III century. It is the dialect of Babylonian private documents, and from the XII century, of all Jewish private documents in Aramaic. It is based on Hasmonean with very few changes, probably because many of the documents in Hasmonean were legal documents, so the language had to be common to Jews in general, and Hasmonean was the old standard back then.

Nabataean Aramaic was the language of the Arab kingdom of Petra, which between 200 B.C. C. and 106 d. C. included the eastern bank of the Jordan, the Sinai peninsula and northern Arabia. The Nabataeans preferred Aramaic to Arabic probably because of their caravan trading activities. The dialect was based on Achaemenid with some influence from Arabic, modifying the l to n and using certain foreign words. There are Nabataean inscriptions from the early kingdom, but most date from the first four centuries AD. The language was written with cursive characters forerunners of the modern Arabic alphabet. The use of foreign words increased until in the IV century, Nabatean merged with Arabic.

Palmyrean Aramaic is the dialect spoken in the city of Palmyra, in the Syrian desert, from 44 B.C. C. until 274 a. C. It was written with rounded characters, which later gave way to the Syriac alphabet. Similar to the Nabatean, it was influenced by Arabic, although to a lesser extent.

Arsacid Aramaic was the official language of the Parthian Empire between 247 B.C. C. and 224 a. C. It was the one that continued the tradition of Achaemenid Aramaic made official by Darius, although over time it suffered the influences of spoken Aramaic, Georgian and Persian. After the conquest of the Parthians by the Sasanian Empire, Arsacid exerted considerable influence on the new official language.

Late Eastern Old Aramaic

All the dialects mentioned in the previous subheading were descendants of Imperial Aramaic. Notwithstanding this, the various regional dialects of Late Ancient Aramaic coexisted with those, often as spoken languages. Evidence for these dialects is known only through their influence on words and names over a more standard dialect. However, these spoken dialects became written languages in the II century BCE. C. and reflect a stream of Aramaic dialects that were not dependent on Imperial and show a clear division between the regions of Mesopotamia, Babylonia in the east, and Judea and Syria in the west.

In the east, Palmyrean and Arsacid dialects mixed with regional languages, creating a mix between imperial and regional dialects. Arsacid later became Mandaean, the ritual language of Mandaeanism.

In the kingdom of Osroene, centered on Edessa and founded in 132 BC. C., the regional dialect became the official language, Old Syrian.

Eastern Mesopotamian Aramaic flourished on the east side of the Tigris, with evidence at Hatra, Assur, and Tur Abdin. Tatian, the author of 'Diatesaron', was originally from Assyria and possibly wrote his work in Eastern Mesopotamian rather than Ancient Syrian or Greek. In Babylonia, the regional dialect used by the Jewish community was Jewish Old Babylonian, which was increasingly influenced by Biblical Aramaic and Babylonian Targumic.

Late Western Old Aramaic

Western regional dialects of Aramaic followed a similar course to those of the East, although they are quite different from Imperial Aramaic and eastern dialects. Aramaic came to coexist with Canaanite dialects, eventually displacing Phoenician in the I century BCE. C. and Hebrew in the IV century d. c.

The best-attested form of Late Western Old Aramaic is that used by the Jewish community. This form is known as Old Jewish Palestinian, its oldest form being Old East Jordanian, which probably came from the region of Caesarea Philippi. This is the dialect in which the oldest Enoch manuscript (170 BC) is written. The next distinctive phase of the language is known as Old Judaic around the II century. This language can be found in various inscriptions and personal letters, preserved quotations from the Talmud, and receipts from Qumran. The first edition of "The War of the Jews" by Flavio Josefo was written in ancient Judaic.

Old East Jordanian continued to be used around the I century by pagan communities east of the Jordan River, This dialect is also known as Old Pagan Palestinian. It was written in a cursive script similar to that of Old Syrian. There is a possibility that an Old Christian Palestinian dialect arose from the pagan, which may be related to a tendency towards Western Aramaic found in the Old Syrian Gospels (see Peshitta).

Dialects spoken in the time of Jesus

In the vicinity of Israel—in addition to the Hebrew dialects of Khumran and the Mishnah (extensively attested in the Dead Sea Scrolls)—seven dialects of Western Aramaic were spoken at the time of Jesus. They were probably distinct but mutually intelligible.

Old Judeo was the dominant dialect of Jerusalem and Judea. In the Ein Gedi region, the Southeastern Judeo dialect was spoken. Samaria had its own distinctive dialect, Samaritan Aramaic in which the consonants he, jet and ayin were pronounced all as alef.

Galilean Aramaic, the dialect of Jesus' home region, is known only through a few place names, Targumic Galilean influences, some rabbinic literature, and a few private letters. It was probably characterized by the fact that diphthongs were never simplified to single vowels.

Several dialects of east Jordanian were spoken east of the Jordan. In the region of Damascus and the mountains of Anti-Lebanon, Damascene Aramaic was spoken, deduced from modern Western Aramaic. Finally, to the north in Aleppo, the western dialect Orontean Aramaic was spoken.

In addition to Hebrew and Aramaic, Greek was used in urban centers, although the exact roles of these spoken languages are still a matter of debate. It is suggested that Hebrew was a local language, Aramaic an international language of the Middle East, and Greek the administrative language of the Roman Empire. The three languages influenced each other, especially Hebrew and Aramaic, with the incorporation of Hebrew words into Jewish Aramaic (especially religious words). Conversely, Aramaic words entered Hebrew.

Similarly, the Greek version of the New Testament often retains non-Greek Semitisms, including transliterations of Semitic words:

- Some of Hebrew origin: the order of Jesus Ephphatha, εφαθα, a form of the imperative hippataj, أعربية, «Be open!».

- Others of Aramaic Origin: the word Talitha, Ταλιθα, which can represent the noun 국alyěthā, ,,,...........................................

- And others that can be both Hebrew and Aramaic, and Rabbounei queαβουνει that may be Ribboni, מוה, «my teacher» in both languages.

The evidence suggests a complex linguistic environment, and care needs to be taken when analyzing data.

In 2004, the production of the film The Passion of the Christ made extensive use of dialogues in Aramaic, especially reconstructed by William Fulco. Despite the efforts, Aramaic speakers described the language used as forced and unfamiliar. In addition, the Aramaic used in the film is Syriac Aramaic from the VII century and VIII and not Palestinian Aramaic as used in Judea in the I century.

Middle Aramaic

The III century is considered the chronological boundary between Old Aramaic and Middle Aramaic, since during this century the nature of various Aramaic languages and dialects begins to change. The descendants of Imperial Aramaic cease to exist as living languages, and the regional languages of the East and West began to produce new literatures. Unlike many of the Old Aramaic dialects, quite a bit is known about the vocabulary and grammar of Middle Aramaic.

Middle Eastern Aramaic

Only two of the eastern Aramaic languages continued to exist in this period. To the north of the region, Old Syriac became Middle Syriac; while to the south, the Old Babylonian Jew produced the Middle Babylonian Jew. Simultaneously, the post-Achaemenid Arsacid dialect became the forerunner of the new Mandaean language.

Middle Syriac

Middle Syriac is the classical, liturgical, and literary language of today's Syrian Catholic Church. Its heyday was between the IV and VI, beginning with the translation of the Bible into this language, the Peshitta and the prose and poetry of Ephrem of Syria. Unlike its predecessor, Middle Syriac is a distinctly Christian language, though over time it became the language of those who opposed the Byzantine leadership's dominance of the church in the East. Missionary activity led to the spread of Syriac through Persia, India, and China.

Middle Babylonian Jewish Aramaic

Middle Babylonian Jewish Aramaic was used by Jewish writers in Babylonia between the IV and XI. It is most commonly identified as the language of the Babylonian Talmud, completed in the VIIth century century, and Post-Mudic literature, which are the literary products most important of Babylonian Judaism. The most important epigraphic sources for this dialect are the hundreds of Aramaic magic bowls inscribed with Jewish characters.

Mandaean

Mandaean is a sister dialect of Babylonian Jewish Aramaic, although it is both linguistically and culturally distinct. Classical Mandaean is the language in which Mandaean religious literature was composed. It is characterized by a highly phonetic spelling.

Middle Western Aramaic

Dialects of Old Western Aramaic continued into Middle Jewish Palestinian, Samaritan Aramaic, and Christian Palestinian. Of these three, only the average Jewish Palestinian continued as a written language.

Middle Jewish, a descendant of Old Jewish, ceased to be the dominant dialect and was used only in southern Judea. Similarly, Middle East Jordanian continued as a minor dialect derived from Old East Jordanian.

Middle Jewish Palestinian Aramaic

In 135, after the Bar Kochva revolt, many Jewish leaders expelled from Jerusalem moved to the Galilee. The Galilean dialect then emerged from obscurity, and became the standard for Jews in the West. This dialect was spoken not only in Galilee but also in the surrounding areas. In this language was composed the Jerusalem Talmud, completed around the V century, and the Midrashim, a series of commentaries and teachings Biblical. The modern standard for vowel punctuation in Biblical Hebrew (X century Tiberian system) is most probably based on the pronunciation of the Galilean dialect of the average Jewish Palestinian.

Samaritan Aramaic

The Aramaic dialect of the Samaritan community is attested for the first time by a documentary tradition that can be dated back to the IV century. Its modern pronunciation is based on the form used in the X century.

Palestinian Christian Aramaic

The language of Aramaic-speaking Western Christians is evident from the VI century, but probably existed as early as the IV. The language itself comes from Old Christian Palestinian, but its writing conventions were based on Early Middle Syrian and heavily influenced by Greek (The name of Jesus, Aramaic Yeshu, is is found written as Yesûs in Palestinian Christian).

Modern Aramaic (Neo-Aramaic)

Today one of the Aramaic languages is spoken by more than 400,000 people, including Jews, Christians, Muslims, and Mandaeans who live in remote areas, preserving their traditions through print and, more recently, electronic media. The modern Aramaic languages are now further apart from each other than at any time in history, due to the political instability of the last two hundred years in the Middle East that has affected modern Aramaic speakers, producing a worldwide diaspora. In the year 1915, the Aramaic-speaking Christians living in eastern Turkey were subjected to persecutions that marked the end of the Ottoman Empire. In 1948, the newly founded State of Israel attracted the majority of Aramaic-speaking Jews. However, this migration has caused small groups of Neo-Aramaic-speaking Jews to be literally lost within a sea of modern Hebrew speakers, which could make the extinction of many Jewish Aramaic dialects imminent.

Modern Eastern Aramaic

Modern Eastern Aramaic exists as a wide variety of dialects and languages. There is a significant difference between the Aramaic spoken by Jews, Christians, and Mandaeans. Two of the most important varieties are Assyrian Neo-Aramaic and Mandaean.

Christian languages are often called Modern Syriac, Modern East Syriac or East Neo-Aramaic (also called Sureth or Suret) and are found profoundly influenced by the Middle Syrian liturgical and literary language. However, these dialects also have roots in numerous mainly oral local dialects, and are not direct descendants of Middle Syrian. The dialects of this group are not mutually intelligible.

Modern West Syriac, also called Central Neo-Aramaic, is generally represented by Turoyo, the language of Tur Abdin. A related language, mlahso, has recently become extinct.

Modern Jewish Aramaic languages are currently spoken primarily in Israel, and most are considered endangered. The Jewish dialects from the communities that lived between Lake Urmia and Mosul are not intelligible. In some places like Urmia, Christians and Jews speak unintelligible dialects of Modern Eastern Aramaic in the same place. In others like Mosul, the dialects of both religions are similar and allow for conversation.

Some Mandaeans living in Iran's Khuzestan province speak Modern Mandaean, which is very different from any other Aramaic dialect.

Modern Western Aramaic

Very little remains of Western Aramaic. It is still spoken in the Christian town of Maalula in Syria, and in the Muslim towns of Bakh'a and Jubb'adin, as well as by some people who migrated from these towns to Damascus and other cities in Syria. All the speakers of these dialects also speak Arabic, which is the main language in these towns. It is in serious danger because there are no standardization and dissemination policies.

Lexical comparison

The numerals in different modern Aramaic variants are:

| GLOSA | Northeast | Turoyo | Western | PROTO- ARAMEO | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aramaic Assyrian | Barzani | Aramaic of Bohtan | Caldeo | Hertevin | Hulaulá | Lishan Didan | Lishana Deni | Lishanid Noshan | Mandeo | Senaya | ||||

| '1' | xa | xa | xa | xa book | haa | xa | xa | xa | xa | hødɔ | xa | ðo | ・ | ♪ |

| '2' | tr | tre | tra | tre | terte | tre | tre | tre | tre | train | tre | tre | iθ | ♪ |

| '3' | t tla devoted | talaa | t tlota | t tla devoted | T tlata | tělhaa | taha | t tlaa | ## | klː intended | t tla gravesaa | tloθo | eθlθ | *tlāθa |

| '4' | arpapa | Русский | arba | Årba | Årba | Årba | arba | Årba | Årba | ⋅ | Årba | aroboo | | * apostlearbāʕ |

| '5' | xam≤ | xam≤ | xam≤ | xam≤ | h ham≤a | xam≤ | xam≤ | xam≤ | xam≤ | hѕmьɔ | xam≤ | amamь | ・mme・ | *amam cleana |

| '6' | θta | ◊ | θta | ◊ | Åæri | ◊ | θta | ◊ | Русскийta | /25070/tth | Åæri | ≤2 | seθ | * coins. *giletta |

| '7' | ・awwa | ・u markwa | ・awa | ¢Ü ¢Ü | ¢Ü ¢Ü | giloa | uritwa | Đa | ¢Ü ¢Ü | gilww | ・owa | ・awoo | e≤3 | *ritabaa |

| '8' | tmanya | tmanya | tmanya | tmanya | tmanya | tmanya | tmanya | tmanya | tmanya | thımː | tmenya | tměnyo | θmo devoted | *tmanya |

| '9' | Русский | Русский | Русский | ". | Русский | gul a | Русский | gul a | Русский | ▪ | teritaa | . | e e・ | ♪ you cleaned up ♪ ¶¶ |

| '10' | θRA | Русский | ► | ∅sraa | gulchesaa | gulsraa | ► | ∅saraa | Åisra | æsrɔ | esra | asasroo | ess・ | ♪ |

Linguistic description

Phonology

The reconstruction of the phonology of the different stages of Aramaic is complicated due to the scarcity of data regarding some aspects, and that the writing system is only consonantal. Although from time to time there are transcriptions of Aramaic terms in Akkadian, Greek, or Demotic where the vowels are marked, this evidence is fragmentary and difficult to interpret. The consonant inventory for Archaic Aramaic has been reconstructed as:

| Labial | Coronal | Dorsal | Gutural | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inter-dental | Alveo-dental | Palatal | Velar | Uvular | Faringal | Gloss | |||

| Occlusive | sorda | p | t | k | . | ||||

| Sonora | b | d | g | ||||||

| emphatically | ".. Δ ▪ | (k). q ▪ | |||||||

| Fridge | sorda | θ Δ š ▪ | s | š | < ḥ ▪ | h | |||

| Sonora | ð. z ▪ | z | |||||||

| emphatically | θ ’. . ▪ | s ".. . ▪ | |||||||

| Lateral | sorda | . š ▪ | |||||||

| Sonora | l | ||||||||

| emphatically | ʼ. q ▪ | ||||||||

| Sonorante | w | j. and ▪ | . r ▪ | ||||||

| Nasal | m | n | |||||||

In the table above, a sign is indicated only when the phoneme and its transcription use the same letter, and only when they differ is the usual transcription given. Note that each of the graphemes < z, ṣ, q > is used to transcribe two different phonemes, while < š > transcribes three different phonemes, this is because in later stages of Aramaic the original phonemic distinctions were lost. As for the oldest vowel inventory, it would have been /i, ī, a, ā, u, ū/, identical to that of Proto-Semitic. This system underwent notable changes in later stages:

- Imperial Aramaic, in this stage were given the change /./ /s/, /./ / y/ and /θ, ð, θ/ θ /t, d, t/. These changes significantly reduced the number of dental consonants. These changes were reflected in the writing: so the fonema /ð/ written initially. z passed to write d and something similar happened to the fonemas that changed.

- Aramaic half, /a/ /i/ in closed syllables, the /i, u/ tónicas became /e(towards), o(towards)/, in all the dialects /ai/ /ei/ and /au/ /o book /ou/ (although these changes were given at different times in each dialect, although they all ended up experiencing them). In addition, in the first pretonic syllable the short vowels are lost (although if a complicated consonant group occurs the position of the vowel is marked by [øn]). Also at this time the vocálica quantity ceases to be phenomically distinctive. In some dialects, not all, there are also changes such as /ā/ /2005 ///, /u/ atona /2005 /// in some photontic contexts, /i, a/ atonas 국/ in some photontic contexts. Thus in the dialects that experienced all these changes the vocálic system became heptavocálico /i, e, מ, a,., o, u/ (while in one where the last changes did not occur would remain as pentavocálico /i, e, a, o, u/.

- Aramaic lateAt this stage there were various vocalic systems, or at least diacritic systems to denote the vowels, these systems depended on the different dialects distinguishing the Tiberian Aramaic, the Babylonian Aramaic, the Nestorian Aramaic and the Jacobite Aramaic.

Contenido relacionado

Ramiro I of Aragon

Pedro de Heredia

Mozarabic