Arabic calligraphy

Arabic calligraphy (in Arabic, فن الخط [fann al -jaṭṭ], "line art"; in Persian, خوشنویسی [joshnevisí], "writing bella") is a decorative art typical of the peoples who use the Arabic alphabet and its variants. It is usually considered as the main of the Islamic arts.

Symbolism and function in Islam

The art of calligraphy developed alongside Arabic script itself and Islam, for both utilitarian and artistic writing. This duality is perceptible throughout Islamic history, and calligraphy occupies a leading role, becoming the Islamic art par excellence.

According to Mr. Saïd Saggar, this importance and antiquity of the art of calligraphy must be linked above all to the importance of the basic material of the calligrapher, the letter, in Arab culture. The calligrapher thus remembers that:

The letters and characters have, among the Arabs, an extremely strong mode of existence and presence, rarely matched in other places. The letters constitute a set of symbols and significants endowed with considerable wealth and social and spiritual influence.Saggar (1993, p. 105)

Thus, several suras of the Qur'an are introduced by certain isolated letters (muqattaʿat) around which there are numerous interpretations (exegesis or in Arabic, tafsir); Similarly, a hadith said by al-Bukhari and Muslim attributes to Muhammad the words "this Qur'an has been revealed in seven letters." The letters are widely used in the field of the irrational (divination, amulets, astrology, etc.). The mystics have recovered the subject to a great extent.

The interest in the letter awakened the passion for the art of the letter, so that the calligraphy became the celebration of its multiple meanings keeping the search for an aesthetic that makes the calligraphic text readable, understandable and loved at the same time.Saggar (1993, p. 102)

The particular status of the Qur'an and the Word in Muslim revelation are also essential issues in the development of calligraphic art in Islamic lands. In a religion where God has spoken, where divine revelation has been transmitted by the Archangel Gabriel in Arabic, copying the Qur'an is an act of mercy. The book itself is an object that takes on special importance in Islamized societies.

However, calligraphy is not just a sacred art. It is also a visual marker of Islamic society, as evidenced by the use, beginning with the reforms of ʿAbd Al-Malik (696-699), of entirely aniconic and epigraphic coinage. According to Oleg Grabar, this decision is a way for the Umayyad caliph to affirm the cultural originality of his empire against Byzantine and Sasanian models, in objects with official and symbolic value. This conception of writing and calligraphy as a cultural and artistic mark of Islam is comparable to the difficulties and disputes that arose, during the same period, around figurative representation. For O. Grabar, the fact that "Arabic writing proved to be the main iconographic and ornamental process" during the formative period of Islamic art is one of the few elements that gives Islamic art a semblance of unity.

Origins

The development of Arabic calligraphic art, like that of writing itself, is closely linked to the spread of Islam from the 7th century on. Until that time, Arab culture was transmitted mainly orally, and although the Arabs had their own alphabet, they did not use writing except for mnemonic notes, business accounting, epitaphs, and other minor uses. In the Arabic alphabet of the time, there were no points that today distinguish one letter from another: thus, for example, the letters "ب", "ت", "ث&# 3. 4; (th, t, b) were written the same, since only the basic stroke common to all of them was written. The reader had to make an extra effort of interpretation depending on the context, which was generally not a problem since the reader was often the writer himself or someone who in any case already had an idea of what was written.

The formation of the umma (Islamic State), first in Arabia and then in non-Arabic speaking territories, raises two questions. First, the need to fix the text of the Quran to facilitate its transmission between non-Arabic speakers, while guaranteeing the inalterability of the text. It is then that the alphabet is perfected so that each sign represents a single sound: the dot is invented, from which different letters are created by adding it to what until then were common strokes to represent different phonemes. Later a vowel notation will be invented that is added to the writing as diacritics. The Arabic script is definitively fixed around the year 786 with the contributions of Jalil ibn Ahmad al-Farahidi. The second issue raised is that as the Islamic State grows, administration becomes more complex and requires a volume of paperwork unheard of in the pre-Islamic Arab tribal organization. This drives the improvement of writing, which becomes faster and clearer, as well as the proliferation of different styles.

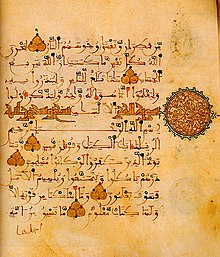

In the early days of Islam, there were basically two calligraphic styles, related to the support of writing. On hard materials, more schematic letters were engraved, with a square appearance, while for soft supports a cursive letter was used. The first style will give rise to Kufic writing, so called because it was developed in Kufa (Iraq), of an ornamental and solemn nature which in turn will lead to various styles. It also gives rise to the italics traditionally used in the Maghreb and al-Andalus, as well as in the areas of Africa that are under their influence. From the original cursive comes the nasji style or "copy" style, which is the one used to this day as a model of print, which in turn will give rise to very different forms of writing. varied, among which stands out the ruqʿa, schematic cursive used today in manuscript writing, especially in Mashreq.

The development of calligraphy as an art is linked to the fact that Islam forbids the worship of figurative representations and that is how calligraphy offers a substitute for figurative decoration in holy places. Instead of representing God or the prophet, or any other figurative motif related to religion, Islamic art replaces them with the calligraphic representation of their names, or with phrases taken from the Koran, particularly the basmala. Arabic writing in general, apart from its artistic use, underwent a true revolution in the Islamic period, taking into account the marginal use that had been made of it in previous times. Medieval Islamic societies, predominantly urban, have a high degree of literacy, and educated people pride themselves on mastering different calligraphic styles. Oral transmission is maintained by tradition, especially in the case of the Koran, whose scholars will continue learning it by heart, but at the same time an interest arises in leaving a written record of everything that happens, is fabled or thought, giving rise to a very extensive literature. Muslims justify this interest in scripture by arguing that the first word that was revealed to them by God is the imperative "read" (iqrā'), which heads the first words that according to tradition God spoke. to Muhammad:

"Read, in the name of your Lord, who has created,He created the man from a blood clot!

He has taught the man what he did not know. "

Lee! Your Lord is the Giver,

that has taught the use of lime,Quran 96.1-5

Technique

Calligraphy begins to develop beyond its functional use with the calligrapher Abu Ali Muhammad Ibn Muqla (d. 940), who was vizier to three Abbasid caliphs. Ibn Muqla and his brother established the first rules of proportion in the drawing of the letters. They took as their main measure the point, that is, the rhombus drawn with the pen, to measure the length of the lines and the circle with a diameter equal to that of the letter alif (ا) to calculate the proportions of the letters. Styles derived from the original italics are governed by these units of measurement.

The usual instrument for writing is the pen (in Arabic, qalam), still used today for artistic calligraphy. The calamus is a cane at the end of which a transversal cut is made: this cut determines the alternation between thick and thin strokes characteristic of most calligraphic styles. In the Maghreb and Al-Andalus, however, a pointed pen was used more frequently, like the traditional European pens, and for this reason the so-called Andalusian or Maghreb script does not have alternation in the stroke. There are less well-known calligraphic styles that use other instruments: the Muslims of China, for example, used the brush characteristic of Chinese calligraphers, giving Arabic calligraphy executed in this way a very peculiar appearance.

Main styles

All the classical forms that Arabic characters adopt derive from one of the two scripts used in pre-Islamic times: cursive and hiri, later called Kufic.

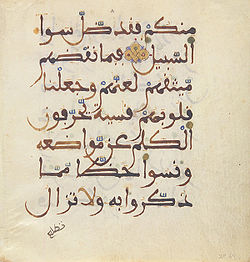

Nasji or nasji

The nasj is the most basic style of Arabic calligraphy, derived from the ancient pre-Islamic cursive and the rules devised by Ibn Muqla and Ibn al-Bawwab. The term nasj derives from the verb nasaja (نَسَخَ), "to copy". It was developed in the 10th century, modified in the 15th century by the Ottomans, and is still in use today. It is a writing of small and balanced characters. The vertical strokes are skewed to the left, while the bottom ends of the horizontal ones tend to point upwards. The ratio of high ink densities and that of fine lines, as well as that of curves and straight lines, are similar and harmonious. The speed of both writing and reading is fast.

It replaced other styles of Arabic calligraphy in book printing, as it is the most legible of all the varieties. It was adapted to be printed and, at present, it is the most used style by far.

Ruqʿa

The ruqʿa, derived from the nasj, is not an ornamental style but a functional one. Its name means "piece", because it was developed to be able to write on small pieces of paper, so that the largest amount of text could fit in the smallest possible space. It does this by simplifying the shape of the letters, completely eliminating ornamentation and diacritics, and tending to slant words so that some characters can overlap others. The colon becomes a horizontal dash, the three dots become a sort of circumflex, and the single dot is halved so as not to be confused with the dash. The ruq`a is the most widely used style in handwritten writing today, especially in the countries of the Mashreq (Arab East).

Kufic

The kūfī or Kufic is named after the city of Kufa, where it developed from the 8th century. It is the oldest style: it was previously called hiri, after the city of al-Ḥīra, the capital of the Lájmida kingdom, and is originally influenced by the Syriac alphabet. It is characterized by having pronounced angles and an overall square air. In order not to break their solid air, often the dots of the letters are reduced to small, almost imperceptible lines. It is one of the most widely used styles even today in signs and decoration and the one with the most variations, apart from having given rise to the North African and Andalusian styles. Among its variants are:

- the flowery cubicin which the strokes acquire certain plant traits and intersect.

- the geometric cubic, in which the letters stylize and simplify forming geometric figures. It is one of the most used styles in decoration, especially in mosaic and tile, to which it adapts perfectly since it can be reduced to an addition of squares. Inscriptions in geometric cubics are frequent, adorning the outer walls of mosques, alminars or the base of the domes.

Zolight

The thuluth resembles the nasj, from which it is derived, but the letters are longer in proportion to the thickness of the line. It developed in the 13th century as an ornamental style, in competition with the Kufic. The original thuluth quickly gave way to a variety called warped thuluth, in which the letters are lengthened or shortened at will to fit the script into the space in which it is inscribed (usually a rectangle). The gaps left by the long letters are usually filled with diacritics or purely ornamental signs with no other value than making the whole harmonic. A good example of this style is the inscription that appears on the flag of Saudi Arabia.

Persian Styles

The fārsī (Persian) style and its derivatives come from the nasj and originated, as its name suggests, in the regions of Asia influenced by for Persian culture. It comes from the ruq`a and like this, it is generally characterized by the simplification of the letters, the horizontal elongation of the strokes and the alternation of sizes between some letters and others. Among the styles of Persian origin, one of the most famous is the nastaʿliq, a clearly oriental style whose name comes from nasj taʿliq, that is, "nasj pendant". It is called this way because, as in other oriental styles, not all the letters are arranged on the line of writing: the words tend to start a little above the line and end just above the line, giving the impression that they are hanging.. This also allows the words to be mounted slightly on top of each other. It has a very pronounced alternation between thick and thin lines, which is achieved by alternating two pens, one triple the thickness of the other. In addition, the pen is usually rotated when drawing a stroke, which causes it to change thickness, something unusual in other styles, in which the pen always forms the same angle with respect to the surface on which it is written. nastaʿliq is the preferred style for block letters in Urdu and other languages of the Indian subcontinent that use characters of Arabic origin (see Urdu Wikipedia).

Diwani

The dīwānī style, also derived from nasj, owes its name to the fact that it was used in administration (dīwān ) of the Ottoman Empire. It was invented by the calligrapher Husam Rumi from the Persian style taʿliq, the predecessor of nastaʿliq, and became popular during the reign of Suleiman the Magnificent (1520–1566). It is a very ornamental Baroque style, characterized by its elongated and curved lines and because it prolongs the strokes in such a way that letters are often joined together that should not be: it is common to try to write words or entire phrases in dīwānī without lifting the pen from the paper. The space between words is also shortened. This style gave rise to another, even more baroque, called yallī dīwānī or dīwānī sublime: as in the thuluth, empty spaces are filled using diacritics and ornamental signs.

Maghrebi and Andalusian styles

An important style —or set of styles— is the so-called Andalusi or Maghrebi, which bears little relation to the others because, unlike them, it does not derive from nasj but from Old Kufic. It is the form of writing traditionally used in Al-Andalus, Northwest Africa and by the Muslim peoples of West Africa. It is executed with a different pen from those commonly used, as it has a sharp point similar to those of European feathers. For this reason, it has little thickness in the line and it is usually uniform. It escapes the rules of proportion applied to the other styles, thus granting greater freedom of execution.

Calligraphic compositions

Calligraphy is often used to make drawings or artistic compositions that represent objects, plants or animated beings, or simply harmonic forms such as symmetrical compositions or geometric figures. These compositions are not intended to communicate a text but to show the skill of the calligrapher: in general they are very difficult to read and for this reason they usually reproduce messages that the viewer already knows. Most commonly, it is the basmala or Muslim ritual invocation, the shahada or profession of faith, or short chants from the Koran that Muslims know by heart.

The oldest examples are those that form geometric figures using the script called Geometric Kufic. As for the compositions made with italics, those that reproduce animals or fruits are classic. Drawings are also a classic subgenre. «in mirror», double compositions in which the original motif is then reproduced in the form of a specular reflection, showing through this symbolism the double expression of the human being, its visible material part –the body with its different manifestations– and the internal, represented by the psychological world.

Among the calligraphic compositions we must mention the tughra (طغراء in Arabic; tuğra in Turkish) or stylized signature of the Ottoman sultans that appeared in the heading of the official documents as a coat of arms. The tugras have a common characteristic shape, and apart from a few small details, only the name of the sultan that appears on it varies.

Contenido relacionado

Du gamla, du cold

Gōzanze Myō-ō

Moroccan Arabic