Arabian language

The Arabic, also called Arabic, arabia, or algarabía (in Arabic, العربية al-ʻarabīyah or عربي/عربى ʻarabī, pronunciation: [alʕaraˈbijja] or [ˈʕarabiː]), is a macrolanguage of the Semitic family, like Aramaic, Hebrew, Akkadian, Maltese and the like. It is the fifth most spoken language in the world (number of native speakers) and is official in twenty countries and co-official in at least six others, and one of the six official languages of the United Nations Organization. Classical Arabic is also the liturgical language of Islam.

Modern Arabic is a descendant of Old Arabic. The Arabic language comprises both a standard variety seen in literacy, on formal occasions, and in mass media (fuṣḥà or modern standard - اللغة العربية الفصحى, broadly based on but not identical to Classical Arabic), as well as numerous colloquial dialects, which can sometimes be mutually incomprehensible due to lexical and phonological differences, while they maintain greater syntactic continuity. In general, the dozens of Arabic dialects are divided into two main ones, Mashreq (eastern) and Maghrebi (western). The most understood among Arabs is the Egyptian dialect المصرية العامية, for being the most populous Arab country and also for its production cinematography and its media and artistic presence in general.

The name of this language in the Arabic language itself is [al-luga] al-'arabiyya (the Arabic [language]), although in some dialects such as Egyptian is called 'arabī (in the masculine gender).

Historical, social and cultural aspects

History of the language

The Arabic language belongs to the South Semitic branch of the Afroasiatic family. Arabic literature begins in the VI century AD. C. and can be broadly divided into the following periods:

- Preclassical ArabIn this period there was already a marked dialectal differentiation.

- Classical, based on the language used to write the Quran and the subsequent works that used that variety of Arabic as a model.

- Postclassical Arab or modern standard.

During the post-classical period, varieties of colloquial Arabic emerged, some markedly different from Classical Arabic and Modern Standard Arabic, and are used as spoken languages, in regional television programs, and in other informal contexts.

Preclassical Arabic before Islam

Centuries before the rise of Islam, Arab tribes had already migrated to the regions of Palestine, Syria and Mesopotamia; Arabs were the dominant group among the inhabitants of Palmyra, long ruled by a dynasty of Arab origin, until the Romans destroyed that kingdom in AD 273. C. Between the I century a. C. and the III century d. C., the Nabataeans established a State that reached Sinai in the west, Hijaz in the east and from Mada'in Salih in the south, to Damascus in the north, having Petra as its capital. The Arabic-speaking tribes of Palmyra and the Nabataeans used the Aramaic alphabet as their writing system, but the influence of Arabic is clearly attested in inscriptions using proper names and Arabic words.

The corpus of pre-Islamic texts, covering the 6th and 7th centuries AD. C., was picked up by the Arab philologists of the VIII and IX centuries. but classical Arabic was not a uniform language, as Arabic philologists speak of a dialect divided between the western Hejaz and the eastern Tamim and other Bedouin tribes. The glottal stop phonemes preserved in the eastern dialects had been replaced in the Hijaz dialects by vowels or semi-vowels.

Classical Arabic after the rise of Islam

The Qur'an, the first literary text written in classical Arabic, is composed in a language very identical to that of ancient poetry. After the spread of Islam it became the ritual language of Muslims and also the language of teaching and administration. The increase of non-Arab peoples who participated in the new beliefs on the one hand and the will of Muslims to protect the purity of the revelation on the other, led to the establishment of grammatical norms and the institutionalization of the teaching of the language.

The development of grammatical rules took place in the 8th century, along with a process of unification and standardization of the language cultured. Expressions and forms of poetry in the pre-Islamic and early Islamic periods, as well as the Qur'an, disappeared from prose during the second half of the eighth century. After the creation of a normative Classical Arabic by Arabic grammarians, the language remained basically unchanged in its morphology and syntactic structure, becoming the learned language of the Islamic world.

In its normative form, Classical Arabic was adopted in addition to Muslim educated elites, by other religious minorities such as Jews and Christians. However, the vernacular from the beginning was very different from classical Arabic, which became a language of scholarship and literature even in Arabic-speaking regions. This linguistic situation, in which two different variants of the same language coexist, one low and the other high, is what has been called diglossia. The question of when this diglossia occurs in the Arabic-speaking community is highly controversial. The traditional Arab concept is that it developed in the first century of the Islamic era, as a result of the Arab conquests, when non-Arabs began to speak Arabic; others instead come to the conclusion that diglossia is a pre-Islamic phenomenon.

For many centuries the teaching of Arabic was under the domain of Muslim scholars, not having much place for Jews and Christians, who did not fully share philological education.

Normative Modern Arabic

As a literary and scholarly language, Classical Arabic continues to this day, but in the 19th and 20th centuries new elites arose who, influenced by Western civilization and power, revitalized Classical Arabic and formed a linguistic medium called Normative Modern Arabic, adapted to the issues of modern life. Through the media, modern Arabic has had a wide influence on the public and, beyond being an official language in all Arab countries, it is also the second language throughout the Islamic world, particularly among the religious representatives of Islam..

Modern Arabic differs from Classical Arabic only in vocabulary and stylistic features; its morphology and syntactic structure have not changed, but there are peripheral innovations and in sections that are not strictly regulated by the classical authorities. Added to this are regional differences in vocabulary, depending on the influence of local dialects and foreign languages, such as French in North Africa or English in Egypt, Jordan and other countries.

Use and status

Colloquial Arabic is spoken as their mother tongue by some 150 million people, and is also understood by several million who use it as a Koranic language.

In the regions where the Arabic language is spoken, the peculiarity of diglossia occurs. The term diglossia refers to the fact that the same language has two basic varieties that live side by side, each performing different functions. This is probably a universal linguistic phenomenon, although in Arabic it is a fact that unites the entire Arab world. Except for the speakers of Cypriot Arabic, Maltese, and most varieties of Juba and Chadic, this feature is common to all other Arabic speakers and probably dates back to the pre-Islamic period.

Diglossia can be seen in the fact of using colloquial Arabic for daily life and normative modern Arabic in school; Generally, normative modern Arabic is used in written texts, sermons, university theses, political speeches, news programs, while colloquial is used with family and friends, although also in some radio and TV programs. Normative Modern Arabic is the mark of pan-Arabism, as there is a high degree of unintelligibility among some Arabic dialects, such as between Moroccan and Iraqi.

Geographic distribution

Arabic is one of the world's languages with the largest number of speakers, around 280 million as a first language and 250 million as a second language. It represents the first official language in Saudi Arabia, Algeria, Bahrain, Egypt, United Arab Emirates, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, Morocco, Mauritania, Oman, Palestine, Qatar, Western Sahara, Syria, Sudan, Tunisia, and Yemen. It is also spoken in parts of Chad, Comoros, Eritrea, Iran, Mali, Tanzania, South Sudan, Niger, Senegal, Somalia, Turkey, Djibouti and other countries. In addition, several million Muslims residing in other countries have knowledge of Arabic, for basically religious reasons (since the Koran is written in Arabic). Since 1974 it is one of the official languages of the United Nations.

Dialectology and variants

Linguistically, the main difference between the variants of Arabic is that between the Eastern and Western varieties, each with a certain number of subdivisions:

- Western (or Maghreb):

- Arab Maghreb, often called dārijaincluding:

- Moroccan Arab

- Algerian Arab

- Tunisian Arab

- Libyan Arab.

- Saharan Arab, Algerian-Baroque border, and to a lesser extent in Niger.

- Hassanía (Western Sahara and Mauritania), also in Morocco and Algeria.

- Maltese, which is the most divergent form of Arabic, very influenced by the Sicilian and derived from Tunisian.

- Andalusian Arab.

- Arab Maghreb, often called dārijaincluding:

- Eastern Variants (or Mashrequins):

- Sudanese Group

- The Sudanese Arab, Sudan and Chad.

- Arab Nubi, between Egypt and Sudan.

- Arab Juba, South Sudan

- The Arab Chadian

- The Sudanese Arab, Sudan and Chad.

- Egyptian Group

- The Egyptian Arab, of Egypt; the best known for the rest of the Arab world thanks to cinema and television, especially in its variety of Lower Egypt, which has become a prestigious kind of koiné.

- The Arabic saidi, or Arabic of Upper Egypt.

- The Levantine Arab or Shami of Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, Israel and the Palestinian Territories.

- Lebanese

- Palestinian

- Northern Syrian Arab

- Jordanian Arab

- Palestinian

- Arab Bedawi of Egypt, Israel and the Palestinian Territories

- The Cypriot Arab

- Mesopotamian Group

- North Mesopotamian Arab

- The Mesopotamian Arab, or Iraqi, more similar to the Levantine Arab but with features of the northernmost Arab.

- The Jewish Arab, Mesopotamian Arabic dialect in Iran.

- Arab peninsula

- The Arab Gulf, east of the Arabian peninsula; in Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Iraq, Baréin, Qatar, United Arab Emirates and Oman.

- The Arab Shiji, from the Musandam Peninsula, between the United Arab Emirates and Oman.

- The Najdi Arab from the Najd region in Saudi Arabia and the deserts of Jordan and Syria.

- The Hijazí Arab from the Hiyaz region of Saudi Arabia.

- The Yemeni Arab from Yemen.

- The Arab hadhramí

- The Arab Tihamiyya

- The Arab San'ani

- The Arabic ta'izzi-adeni

- Somali Arab

- The Bahraini Arab, Baréin, as well as in areas of Saudi Arabia and Oman.

- The Arab Barequi

- The Omani Arab

- Arabic dhofarí

- Sudanese Group

Dialectal Arabic and diglossia

Dialectal Arabic refers to the multitude of local colloquial varieties of Arabic. The official and literary language is only one, but the spoken varieties are very different from each other, so that intercomprehension is difficult in many cases. It is often said that the difference between Arabic dialects is the same as that between Romance languages, but this is an exaggeration.

The formation of the dialects is due to several combined factors such as the export of existing dialect varieties in Arabia before the Islamic expansion, the influence of the substrata, the geographical and cultural isolation of some areas and the influence of the Colonial languages. The greatest differences occur between the eastern or Mashreqian and western or Maghrebi dialects.

Today Standard Arabic is generally understood and most Arabs are able to speak it more or less correctly: it is the language of writing, of the Qur'an, of teaching, of institutions and of the media communication. Egyptian Arabic, an oriental dialect with some Maghrebi features, is also widely understood, exported to the entire Arab world through a large number of films, television series and songs.

Example of phrase in various dialects:

- 'Tomorrow I'll go see the beautiful market.'

- Classic Arabic:

- سدا سأرى السوق الجميل

- Gadan, sa-adhabu li-arà a-ssuqa Al-yamila

- Modern Arabic standard:

- سأرى السوق الجميل

- Gadan/Bukra, sa-adhabu li-arà a-ssuqa Al-yamila

- Gadan/Bukra, sa-aruhu li-arà a-ssuqa Al-yamila

- Syrian Arab

- بكرة حروح أشوف السوق الحلو/الجميل

- Bukra, ha-ruh ashuf e-ssuq el-hilu/Al-yamil

- Lebanese

- بكرة حروح أشوف السوق الحلو/الجميل

- Bukra, ha-ruh ashuf e-ssuq el-hilu/Al-yamil

- Egyptian Arab

- بكرة هروح أشوف السوق الجميل

- Bukra, ha-ruh Ashuf e-ssuq el-gamil

- Tunisian Arab

- ultimaدا نروح نشوف السوق الجميل

- Gadan, namshi nshuf e-ssuq el-yamil

- Moroccan Arab

- ultimaدا نروح نشوف السوق الجميل

- Gada, namshi nshuf e-ssuq el-yamil

Dialect differences tend to be reduced due to the impact of the mass media.

Derived Linguistic Systems

Maltese, spoken in Malta, is an Arabic dialect written in Latin script and heavily influenced by Sicilian and English.

- The previous sentence in Maltese: G-ada mma mmur nara s-suq is-sabi-

Arabic has left a large number of loanwords in languages with which it has been in contact, such as Persian, Turkish, Swahili and Spanish. In this last language, the Arabisms come mainly from Andalusian Arabic, a variety spoken in the Iberian Peninsula from the VIII century until the XVI. They were more abundant in the everyday lexicon in medieval times.

Many have passed into Spanish with the addition of the Arabic article (al- and its variations as-, ar-, etc.):

- bricklayer (andalusi al-bannī ́ classic al-bannā ́: "the builder");

- sugar. as-sukkar;

- apricot. al-barqūq: "the plum"

- Oil. az-zayt;

- rental andalusí al-kirē ́ classic al-kirā ́;

- Ivory. al-fīl: "the elephant";

- etc.

Others without article:

- macabro. maqābir: "ceminds";

- I wish. Andal. w šā l-lāh. wa šā' allāh: "and dear God"

- until. ḥattà;

- etc.

There are also numerous place names. Some of them are Arabic adaptations of pre-existing place names:

- Albacete Δ al-basīṭ: "the plain";

- Alcalá Δ al-qal`a: "the fortress";

- Alcázar, Alcàsser al-qagger: "the palace"

- Algeciras Δ al-yazira al-jadr: "the green island"

- Almedina ≥ al-medina: "the city (city)";

- Almería. al-miriya: "the mirror";

- Badajoz ” بيوس Batalyaws;

- Guadalquivir Δ and. wād al-kbīr. al-wādī al-kabīr: "the big river";

- Guadalajara; wād al-ḥajaara: river of stones;

- Medinaceli; madīnat Salīm: "the city of Salim";

- Seville − Išbīliya. Hispalis;

- Jaén. jiayyān: "defiladero";

- etc.

Linguistic description

Classification

It is a language that belongs to the West Semitic subbranch (formed by a total of three languages: Hebrew, Aramaic and Arabic) of the Semitic branch of the Afroasiatic macrofamily. It is the most archaic Semitic language, that is, closest to Primitive Semitic of all those still alive today. It has been a literary language since the 6th century and the liturgical language of Muslims since the 7th century.

The literary form is called in Arabic al-luga al-fuṣḥà ('the most eloquent language') and includes the ancient Arabic of pre-Islamic poetry, the Qur'an and classical literature and the modern standard Arabic, used in contemporary literature and the media. The dialectal forms receive the generic name of al-luga al-‘ammiyya (‘the general language’). There are intermediate forms between one and the other.

Relation to other Semitic languages

The Arabic language is closely related to other Semitic languages, especially Hebrew. This relationship is perceived both in the morphosyntactic and in the semantic.

| Spanish | Arab | Hebrew |

|---|---|---|

| water | ماء (mā.) | (májm) |

| peace | سلام (salām) | מוווה (хлаm) |

| father | أب (.(b) | Русский.(av) |

| Day | يوم (jáwm) | (jom) |

| death | موت (mawt) | (mavét) |

| alms | صدقة (Gradaqa) | ה (tsedáka) |

| head | رأس (ra.(s) | ה (roусский) |

| ♪ | أنت (.anta) أنت (.(anti) | אה (.ata) Русский.(a) |

| soul | نفس (nafs) | أعربية |

| house | بيت (bájt) | (bájt) |

| Me. | أنا (.anā) | Русский.(chuckles) |

| heart | (lub) or قلب (qalb) | (lev) |

| Hebrew | عبرية?ibríjja) | ” ivrít) |

| Arabic | عربية?arabbijja) | . aravít) |

Writing system

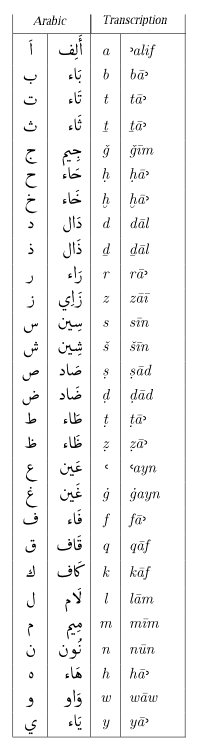

Arabic uses its own writing system that is written from right to left, joining the letters together, so that each letter can have up to four forms, depending on whether it is written alone, at the beginning, in the middle or at the end of the word.

With very few exceptions, each grapheme corresponds to a phoneme, that is, there are hardly any silent letters, omitted letters, or letters that in certain positions, or joined to others, have a different value from the one that corresponds to them in principle. The exceptions are usually due to religious tradition.

In spoken Arabic some letters have different values, depending on the region, than they do in Classical Arabic. Typically, these local pronunciation idiosyncrasies are maintained when the speaker uses Standard Arabic.

In Arabic there are no capital letters. There was an attempt to introduce them in the 1920s, but it was not accepted. Since Arabic proper names often have meaning, they are sometimes enclosed in parentheses or quotation marks to avoid confusion.

Arabic has incorporated (and adapted in some cases) the punctuation marks of European languages: the period, the comma (،), the semicolon (؛), the question mark (؟), etc. The ellipses are usually two and not three.

Phonetics and phonology

Vowels

Modern Standard Arabic has three vowels, with short and long forms: /a/, /i/, /u/. There are also two diphthongs: /aj/ and /aw/.

Consonants

The consonant inventory of Arabic is made up of the following phonemes:

| Labial | Interdental | Dental/Alveolar | Postalveolar | Palatal | Velar | Uvular | Faríngea3 | Gloss | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simple. | emphatically | Simple. | emphatically | |||||||||

| Nasal | m | n | ||||||||||

| Occlusive | sorda | t̪ | t̪ˁ | k | q | . | ||||||

| Sonora | b | d̪ | d̪ˁ | Русский1 | ||||||||

| Fridge | sorda | f | θ | s | ˁ | MIN | x~χ4 | h | ||||

| Sonora | ð | ð~~zˁ | z | 4 | ||||||||

| Approximately | l2 | j | w | |||||||||

| Vibrante | r | |||||||||||

Canciones

Roots and shapes

As in the rest of the Semitic languages, the morphology of Arabic is based on the principle of roots (جذر) and shapes or weights (وزن). The root is most often triliteral, that is, formed by three consonants, and has a general meaning. The form is a root inflection paradigm that frequently also contains within itself a meaning. For example, the union of the verb form istaf'ala (to order to do) with the root KTB (to write) gives the verb istaKTaBa (to dictate, that is, to order that it be written). or make write); with JDM (serve) gives istaJDaMa (to use, that is, to make serve); with NZL (to descend) gives istaNZaLa (to take inspiration, that is, to "bring down" the inspiration). Other examples of paradigms with the root كتب KTB:

- كتب KàTaba: he wrote

- أكتب iKtaTaBa: he enrolled

- كتاب KiTāB: book

- كاتبة KāTiBa: writer / secretary

- مكتبة màKTaBa: library

- مكتب miKTaB: desk

- اكتب uKTuB!: Write!

- تكتبون TaKTuBūna: you wrote

- مكتوب maKTūB: what is written (destiny)

Many times it is possible to guess the meaning of an unknown word by joining the meanings of its root and its paradigm. For example, the word "zāhir" combines a root meaning 'see' with a paradigm of meaning 'what', and this allows us to surmise the word has the meaning 'what is seen'; or 'visible'. This word actually has this meaning. But it also has another, 'arrabales', that we could not have deduced in this way.

The existence of fixed paradigms facilitates the deduction of vowels, that is, inferring the vocalization of words read, but never heard yet.

For example, almost all words that have a written form of the type 12ā3 (the numbers correspond to the radical consonants) are voweled 1i2ā3: kitāb, kifāh, himār, kibār, etc. However, there are also exceptions: the written word "dhāb" ('go') is read "dahāb". As a result, someone who has learned this word by reading it instead of, for example, hearing it in a Qur'anic recitation, will pronounce it, by analogy, "dihāb". According to native experts, who tend to consider Arabic as a spoken language, "dihāb" is bad Arabic, and "dahāb" is the only correct way. According to Western experts, for whom Arabic is a written language and pronunciation details are secondary, the alleged error is so widespread that it must be considered correct, standard Arabic.

Classical Arabic has more lexical forms than colloquial ones. Often many of the original meanings of the forms have been lost, but not those of the roots. Arabic dictionaries organize the words by roots, and within each root the derived words by degree of complexity. This implies the need to know the root to search for the word, which is not always easy because there are irregular roots.

Gender

Arabic has two genders: masculine and feminine. Words that "have a feminine form" are generally feminine, that is, the singulars that end in ة, اء or ى (-ā'h, -a, -à, all these endings sound approximately like the Spanish a), and those that do not have these endings are masculine.

Most exceptions to this rule are feminine with no feminine ending. Between them:

- Those referring to female beings: أم Umm (mother); فرس charades (yegua); مريم Maryam (Mary, his name).

- Wind names.

- Those that can by analogy be considered sources of life and others related to them: شمس šams (sol); نور nūr (light); نار nār (fire); رحم raḥm (uter); أر arroga (land).

- The names of the body parts pairs in number: يد yad (mano); عين ‘ayn’ (eye).

- Others for use: وقس qaws (arco) ب sketchر bi'r (pozo), stakeholderريق ṭarīq (camino).

It is very rare for a word with a feminine ending to be masculine. This is the case of the numerals three to ten in the masculine, and of the word خليفة jalīfa (caliph or jalifa).

The feminine singular of animate beings is almost always formed by adding the ending ة (-at) to the masculine: كاتب kātib (writer) > كاتبة kātiba (writer); مستخدم mustajdim (user) > مستخدمة mustajdima (user); صحراوي ṣaḥarāwī (Sahrawi) > صحراوية ṣaḥarāwiyya, etc.

Some words have both genders, such as قتيل qatīl (dead /a)

Number

In Arabic there are three numbers: singular, dual and plural.

- In the singular one must include the singulatives, that is, those words that indicate unity with respect to a word that indicates collective. For example, زيتونة zaytūna ([una] aceituna) is singulativo de زيتون zaytūn (oil, generic). zaytūna may have a plural. zaytūnāt ([one] olives). The synchronization is made by adding the termination of the female ([a]) to the collective name.

- The dual indicates two units. It forms by adding the termination -ān (nominative) or - Ayn. (accusative/genitive): بحر baḥr (mar) /2005 بحرين baḥrayn (two seas, Baréin). It has its reflection also in the verbal conjugation. In dialectal Arabic the dual is unproductive, reserving in general for already coined uses, and is not used in verbs.

- The plural Arabic offers great difficulty. We have to distinguish between:

- The regular plural: forms by adding the endings ون -ūn o ين - (nominative and accustive/genitive, respectively) in masculine, and termination ات -āt in female.

The masculine plural is mainly used for words referring to human beings. The feminine plural is more widespread, it can be used for animated and inanimate beings and is usually the usual plural of the words with a feminine mark. mustajdimūn (users); مستمدمات mustajdimāt (users).

- The regular plural: forms by adding the endings ون -ūn o ين - (nominative and accustive/genitive, respectively) in masculine, and termination ات -āt in female.

- The plural friction is the most common. It forms by internal bending of the word in singular. Returning to roots and forms, it is about putting the radicals of the singular into another paradigm, which is the plural of that singular. Precision is important, because in most cases there is no way of knowing for certain what plural corresponds to a given singular, nor what singular corresponds to a plural: the speaker must act by analogy or learn the singular and plural of each word. Examples:

- ولد walad (muchacho) pl. أولاد awlād.

- ملاك malak (angel) pl. ملاكة malā'ika.

- كتاب kitāb (book) pl. كتب kutub.

- حمار ḥimār (ass) pl. حمير ḥamīr.

- عالم ‘ālim (ule) pl. علماء 'ulamā' (from where the Spanish word comes from).

In other cases, a certain form of the singular corresponds inevitably to a certain form of the plural. For example:

- قانون qānūn (ley) pl. وقانين qawānīn

- صاروخ ṣārūj (misil; porro) pl. صواري TENawārīj

Sometimes a word has several possible plurals. Standard Arabic tends to simplify and fix, in this case, a single plural form for words that in classical we can find with various plurals, depending on times and places. But despite this trend, it is difficult to know which of the various forms listed in dictionaries is the standard one, since it is extremely normal for more than one to continue to be used.

The differences persist in colloquial dialects as well:

- كاس kās (copa) pl. standard كموس ku'ūs, pl. Moroccan كيسان kīsān.

- حاجة ḥāğa (thing) pl. Egyptian حاجات ḥāğāt, pl. Moroccan حاجات ḥāğāt o حواج ḥawā'iğ

According to grammarians, in words of several possible plurals, the plural forms a12u3, a12ā3, a12i3a, or 1i23a (the numbers are the stem letters), or the regular masculine plural, should be used for sets of three to ten. These forms are called paucales, or plurals of small number. At no time has this rule been strictly followed, but many still say that ṯalāṯatu ašhur ("three months") is more correct than ṯalāṯatu šuhūr.

Declension

Classical Arabic has a declension with three cases (nominative, accusative, and genitive) and two forms (determined and indeterminate) for each case.

The declension usually appears as a diacritic placed over the final letter. Like the short vowels, it is not written except in didactic texts or when there is a risk of confusion:

| case | determined | indeterminate |

|---|---|---|

| nomination | dāru دارة | dārun دار |

| accusing | dāra دارу | dāran داران |

| genitive | dāri دار | dārin دار |

As you can see, the letters that are written are always the same except in the case of the indeterminate accusative, in which the diacritic is placed over an alif (ا). The plural and dual endings have, as we have seen, their own declension that does imply variation in the letters, and the same occurs with some verb forms.

Since they are diacritics, whoever reads a non-vocalized text aloud must understand the text to know which case to pronounce at the end of each word. This implies that the declension does not really add anything to the understanding of the text; in fact it is redundant because its function is already performed by the prepositions and the position of the words within the sentence. It is an archaism used in Arabic above all for its aesthetic value, since a sentence in which all the declensions are pronounced sounds more harmonious to Arab ears because they link some words with others. Standard Arabic often omits inflections that are not reflected in the script, including short word-final vowels. The pronunciation of the declension is common when reading a text, making a speech or reciting poetry, but it is inappropriate and pompous in conversation unless you want to give it a certain solemnity or occurs, for example, among philologists..

Dialectal Arabic omits all declensions: for dual and plural endings it uses only the accusative/genitive form.

Example: "users write long pages sitting in front of the computer"

Classical pronunciation:

- al-mustajdimūna yaktubūna zeruḥufan θālisūna amāma l-ḥāsūb

Pronunciation without inflections:

- al-mustajdimūn yaktubūn zeruḥufan θālisūn amām al-ḥāsūb

Both are spelled the same:

- المستدمون يكتبون صحفا stakeholderويلة جالسون أمام الحاسوب

Dialectalizing pronunciation:

- al-mustajdimīn yaktubū zeruḥuf θālisīn amām al-ḥāsūb

Writing:

- المستدمين يكتبوا صحف أويلة جالسين أمام الحاسوب

Noun phrase

General characteristics of the noun phrase

In its most classic form, the usual sentence order is verb + subject + complements. However, in dialectal forms the subject + verb order is more frequent, which is also frequently used in Modern Standard Arabic. When the verb precedes a plural subject, the verb remains singular. This is not the case if the verb is placed after the subject.

Noun

(morphology: gender, number, case, etc.)

(use: as nucleus, in apposition, etc.)

Adjective

The adjective always comes after the noun. If it refers to people, or if it refers to things and is singular, the adjective agrees with it in gender and number (and case, if the declension is used). However, if the name is a plural of a thing or of living beings (except humans), the adjective agrees with it in the feminine singular. That is, we will say for example:

- a beautiful book: كتاب جميل kitāb[un] janamīl[un]

but in the plural we will say

- a book Nice. (كتب جميلة kutub[un] janamīla[tun])

If the noun is determined by the article al-, the adjectives must be determined as well. Thus, "the Arab world" it will be said al-‘āliam al-‘arabī, that is, the Arab world.

There is a very productive type of adjective called نسبي nisbī or relationship, which is formed by adding the suffix ي -ī (masc.) or ية - iyya (fem.). It is one of the few cases in Arabic of word formation by adding suffixes and not by internal inflection. In Spanish, it has given the suffix -í (masc. and fem.) in words like ceutí, alfonsí, saudi etc The adjective of relationship is used to form demonyms and is common in surnames and words that indicate relationship or belonging:

- تونس Tūnis (Tunisia) تونسية tūnisiyya (Tunecina)

- TECشتراك ištirāk (share, socialize) . ištirākī (socialist)

- يوم yawm (day) أويمي yawmī (daily).

The feminine plural ending (يات -iyyāt) is also used to form nouns:

- يوم yawm (day) أويميات yawmiyāt (daily)

- السودان al-Sūdān (Sudan) 한ودانيات sūdāniyāt (sets of Sudan)

Determinants

In Arabic there is only one specific article, without variation in gender and number, although it does vary in pronunciation. This is the article ال al-, which is written together with the word it determines, which is why it is frequently transcribed in Latin characters separated from it with a hyphen and not with a space.

The l of the article changes its pronunciation to that of the first letter of the given word when said letter is one of the so-called "solares". Half of the letters of the alphabet are solar: tāʾ, ṯāʾ, dāl, ḏāl, rāʾ, zāy, sīn, šīn, ṣād, ḍād, ṭāʾ, ẓāʾ, lām and nūn. The rest are called "polka dots". Thus, التون al-tūn (the tuna) is pronounced at-tūn; الزيت al-zayt (the oil) is pronounced az-zayt, etc. In the Latin transcription, the l of the article can be kept or replaced by the letter solarizada. Dialectal Arabic sometimes solarizes other letters.

On the other hand, the a of the article disappears when the previous word ends in a vowel (which happens very frequently if the declension is used):

- الكتب al-kutub (books) 한ترى الكتب ištarà l-kutub (He bought the books).

In Arabic, in principle, there is no indefinite article, since this value is given by the declension. Dialectical Arabic often uses the numeral واحد wāḥid (one) followed by the definite article:

- classic: كتاب kitābun (a book); dialect: واحد الكتاب wāḥid al-kitāb (lit., "one book").

Pronoun

There are two types of pronouns: isolated and suffixes. The latter, suffixed to a noun, indicate possession: بيتي bayt-ī: "my house"; بيتها baytu-hā: & # 34; his house hers hers & # 34;, etc. When suffixed to a verb, they indicate the direct or indirect object: كتبتها katabat-hā: [she] wrote it (eg, a letter) or [she] wrote (to a woman).

Verb phrase

General characteristics of the verb phrase

The order in the verb phrase is usually subject, verb, complements. A more classical order puts the verb before the subject, and in this case it is always in the singular even if the subject is plural.

As in spoken Spanish, the passive voice has no agent subject: a sentence like Don Quixote was written by Cervantes would be impossible in classical Arabic, which could only express Don Quixote what wrote Cervantes (which is a perfectly correct construction in classical Arabic although its Spanish translation is considered vulgar), or 'the "Quijote was written (it is not known by whom), or well Cervantes wrote Don Quixote. However, standard Arabic, especially that used in the press, gradually incorporates, by imitating European languages, grammatical constructions foreign to the Arabic language, including the passive sentence: Don Quixote was written by part of Cervantes, and the periphrasis of the type was the writing of Don Quixote by Cervantes.

As in other languages, the verb "to be" at present it is not used. To say "I am Arab" we will say: أنا عربي anā ‘arabī, that is, I am an Arab.

But that usually doesn't work when the predicate is determined. The words العالم العربي al-‘ālam al-‘arabī (literally: the Arab world) can only mean the Arab world. If we remove the article from the adjective, tracing the structure of Spanish, we obtain العالم عربي al-'ālam 'arabī, which necessarily means the world is Arab, and never the Arab world.

Sometimes third person pronouns are used to mark the place where the verb "to be" should be, to give a shade of intensity or to avoid confusion: العالم هو عربي al-'ālam huwa 'arabī (the world is Arab): "the world is indeed Arab" (same as inna al-‘ālam ‘arabī). It is better to use pronouns like this only when the predicate is determined: ana huwa l-mudarris (I am the teacher).

Verb

The Arabic verb has two aspects, "past" and "presente", which, more than indicating "time", correspond to the completed action and the action in progress. The imperative and the future are modifications of the present. There is no infinitive. In dictionaries, verbs are stated in the third person masculine singular of the past tense. Thus, the verb "to write" is in Arabic the verb "wrote" (kataba). The present, in turn, has three modes: indicative, subjunctive and jussive, which differ mainly in the final short vowels. In dialectal Arabic all three merge into one.

There are ten different verb paradigms: each root can form up to ten different verbs (see the Roots and forms section). For example, the verbs "naẓara" (looked) and "intaẓara" (waited) both derive from the same verbal root nẓr, in the "1a2a3a" and "i1ta2a3a".

From the verb derive the maṣdar, a name that designates the action of the verb and is frequently translated as an infinitive or a nomen actionis, and the active and passive participles. Both are frequently used in place of the verb. For example, "I am waiting for the subway" can be said:

- using the verb: أنا أنتبر الميترو [anā] antaѕir al-mītrū ("[I] wait for the subway")

- using the active participio: أنا منتexpresر الميترو anā muntaѕir al-mītrū ("soy waiting of the metro")

- using mazer: أنا في أنتبار الميترو anā fī intiѕār al-mītrū ("I'm waiting for the subway")

There is a difference in meaning between the first ("I start to wait", "I am going to wait") and the last two ("I'm waiting").

Adverb

Frequently, the adverb is formed by adding the indeterminate accusative ending -an to the noun (which, remember, is reflected in writing through a final alif):

- سحن ḥasan (good) حسنان ḥasanan (OK)

- شكر šukr (thank you) أعران šukran (thank you)

Complex sentence

General characteristics of the complex sentence

(frequency, syntactic characteristics, formation by conjunctions/affixes, etc.)

Coordination

(copulative, disjunctive, distributive)

Subordination

(adversative, relative, etc.)

Lexicon, semantics and pragmatics

Lexicon

Loans

The Arabic language has incorporated numerous loanwords over time, both classical and standard or dialectal Arabic. The oldest loans, already unrecognizable, come from other Semitic languages such as Aramaic. In medieval times, numerous Persian, Greek, and later Turkish words entered the Arabic language. And in modern times it has incorporated many words of French, English, Spanish or Italian origin. Loanwords are much more common in dialects than in literary Arabic, and affect syntax as well. Words of Tamazight or Berber origin in the Maghreb, Ottoman Turkish in Egypt, Persian and Kurdish in Iraq are frequent.

Examples:

- ورشة warša (staller; standard) workshop (English)

- روية rwīża (wheel; norm) wheel (spanish)

- بندورة bundūra (tomato; Syrian) pomodoro (Italian)

- تليفون tilifūn (telephone; standard) telephone (French)

- كوبري kūbrī (bridge; Egyptian) köprü (whispering)

- دكوردو dakūrdū (all right, Tunisian) Okay. (spanish)

- قانون qānūn (law; standard) ≤3 000 (kánōn) (Greek)

- قيصر qay certify (emperator; standard) cæsar (Latin)

- قصر qagger (palacio; standard) castrum (Latin)

- 한بيزة ṭarabēza (mesa; Egyptian) Δράπία (rape) (Greek)

- بنفسجي banafsiğī (violet; standard) بنفش (banafš) (panting)

Sometimes the loans are integrated into the system of roots and forms, taking from the word incorporated three or four radicals that will serve to create new words according to the usual rules of Arabic derivation. For example, from faylasūf (philosopher, of Greek origin) the quadriliteral root FLSF is extracted, with which words such as falsafa (philosophy), mutafalsif (the one who claims to be a philosopher). Warša and kūbrī, of English and Turkish origin, respectively, have plurals derived from the roots WRŠ in the first case and KBRY in the second: awrāš, kabārī.

Semantics

(peculiarities of the semantic structure of the language, e.g. vigesimal numbering, grammaticalization of the social hierarchy (honorifics), etc.)

Pragmatics

(peculiarities in the use and interpretation of the language according to the context, default contextual assumptions, cultural background assumptions, body language, etc.)

Arabic literature

The Arabic language has a vast literary production that spans from the V century to the present day.

The oldest important samples of Arabic literature are compositions from pre-Islamic Arabia called mu‘allaqat, "hanging". This name is traditionally attributed to the fact that they could have been written and hung on the walls of the Kaaba, then the pantheon of Mecca, for having been victorious in some poetic joust. This would have allowed its survival, given that at the time literature was transmitted orally and therefore it can be assumed that most of its production was lost. The mu‘allaqat are long poems that respond to a fixed scheme that will later inherit, with variations, the classical poetry of the Islamic period. Pre-Islamic poetry has remained in Arab culture as a linguistic and literary model and as an example of primitive values linked to life in the desert, such as chivalry.

The Qur'an and the spread of Islam mark a milestone in the history of Arabic literature. In the first place, it supposes the definitive development of writing and the establishment of the literary language, classical Arabic. Secondly, Arabic-language literature is no longer limited to the Arabian peninsula and begins to develop in all the lands where Islam spreads, where Arabic is the official and prestigious language (later replaced by Arabic). Persian in some regions of Asia). Thus opens the wide field of classical Arabic literature, with a great profusion of genres and authors.

With the fall of Al-Andalus and the Arab powers of the East (Baghdad, Cairo), which will be replaced by the Ottoman Empire, Arabic literature enters a stage of decline, with much less production and little originality compared to the splendor of previous centuries.

Between the middle of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th, depending on the area, the Arab world, and with it its literature, entered the revival process called Nahda (Renaissance). Contemporary Arabic literature breaks away from classical models and profusely incorporates genres such as the novel or the short story and, to a lesser extent, theatre. Poetry continues to be, as in classical times, the most cultivated genre.

The emergence of Arab nationalism in the mid-XX century and up to the 1970s served as a spur to literary development. By areas, Egypt is the country that has given the most writers to contemporary Arabic literature (Naguib Mahfuz the Nobel laureate was from there), followed by Lebanon, Syria, the Palestinian Territories or Iraq.

A famous aphorism declared that "Egypt writes, Lebanon publishes and Iraq reads."

Contenido relacionado

Z

Preposition

Adjective