Aquila adalberti

The Iberian imperial eagle (Aquila adalberti) is a species of accipitriform bird of the family Accipitridae. It is one of the endemic birds of the Iberian Peninsula. Until not long ago it was considered a subspecies of the imperial eagle (Aquila heliaca), but DNA studies of both birds carried out by researchers Seibold, Helbig, Meyburg, Black and Wink in 1996 They demonstrated that they were sufficiently separated to constitute each of them a valid species. The Iberian imperial eagle is a threatened bird; In 2013, four hundred and seven couples were counted in the Iberian Peninsula. Its binomial name commemorates Prince Adalbert of Bavaria.

Description

The plumage of adult specimens is very dark brown throughout the body, except on the shoulders and the upper part of the wings, where it is brown dotted with white feathers. The nape is slightly paler than other parts of the body, and the tail is darker, without light bands or white lines as in the eastern imperial eagle. In the case of juvenile individuals, less than one year old, the color is between brown and reddish, changing to a more or less homogeneous straw yellow color in their second year of life, throughout the second and third years. of life, the specimens adopt plumage phases known as checkerboard, in which the yellowish color is interspersed with increasingly numerous dark brown and black feathers, in the subadult plumage, which appears between the fourth and fifth year. A clear predominance of dark brown is already observed, although still intermixed with lighter colored feathers, reaching the plumage of mature individuals, previously described, in the fifth year, at the same time as sexual maturity. The average size of adults is between 78 and 83 cm in height, and 2.8 kg , although females, larger than males, can reach 3.5 kg. The wingspan varies between 1.8 and 2.1 m.

They live about twenty years on average, with specimens having been documented as being twenty-seven years old in the wild and forty-one years old in captivity.

Habitat

Its territories cover a large number of habitats, from pine forests in mountain areas to dune systems and marshes in coastal areas. Their highest densities are reached on flat lands or with gentle relief, with important, although not dominant, tree formations (dehesas) and with good rabbit populations.

Historically, the persecution of this species meant that the surviving pairs were those that took refuge in areas of difficult access and abrupt relief, generally in mountain areas. Its recovery has led to new couples, and also some old ones, occupying spaces of plain and penilnura.

Within the eagle's territory, its home range, three areas can be distinguished: the nesting area; the nearby feeding area, the most common hunting ground that is defended by the couple for their exclusive use; and the distant feeding area that is used more occasionally, its use is shared with other pairs and other birds of prey, and it is used more outside of the breeding season.

The young, upon emancipation, disperse to areas near or far from where they were born, in search of new hunting and reproduction territories.

Behavior

Unlike the eastern imperial eagle of Eurasia and East Africa, the Iberian species does not migrate. Each pair defends its hunting and reproduction area (about two thousand hectares) throughout the year.

Food

Their food consists of rabbits, which they hunt alone or in pairs. It also preys on hares, pigeons, crows and other birds, and to a lesser extent foxes and small rodents, and may occasionally feed on carrion.

Playback

The Iberian imperial eagle is monogamous. The mating season occurs from March to July, during which the eagles recondition one of the nests they have used for years, rotating from one to another. These nests are located in the tops of trees such as cork oaks or pines. In reforestation areas they have become accustomed to nesting on eucalyptus trees, despite this being a foreign species.[citation required] They nest on both high and low branches.

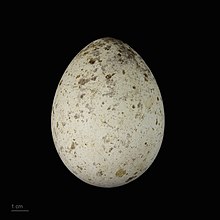

The typical clutch consists of four to five eggs weighing 130 g that are incubated for forty-three days. It is common for up to three eaglets to develop, although this trend has decreased in recent years due to the use of pesticides, which increase the number of infertile eggs.[citation needed] If the year is bad and there is little food, the older chicken hoards it and is the only one that survives; However, it can be said that the Iberian imperial eagle does not practice cainism. When they need to go in search of food, the parents cover the eggs or chicks with leaves and branches to prevent them from being discovered by predators, [citation needed] something that sometimes is not enough, ending with one of the chicks captured by a golden eagle or, in the case of low nests, even a fox or other medium-sized carnivore.[citation needed]< /sup>

The young leave the nest between sixty-five and seventy-eight days after birth, but continue to live nearby and be fed by the parents for four months. After this time, they become independent and begin a nomadic life. When they reach sexual maturity, they usually visit the limits of the territories of sedentary couples in search of a "single" or "widowed" individual of the opposite sex. Young nomads are frequently attacked by pairs of adults into whose territories they have entered.[citation needed]

Evolution of historical distribution and abundance

The regression in the distribution range is weak during, approximately, the period 1850-1890. From this date it intensifies until the end of the first decade of the XX century, becoming scarce in several regions, and during The future of the process is very accelerated. Before the beginning of the decline, it was distributed throughout the Iberian Peninsula except in the north (Catalonia, the Pyrenees, the Cantabrian Mountains and northern Portugal) and in the north of Morocco.

There is a significant lack of information. As mentioned above, by the beginning of the 20th century the species was already scarce. During the period 1850-1890 it is recorded in places where it was rare in the first decade of the following century: the Spanish Levante, the Estrella mountain range and the Alentejo region in Portugal, the Penibetic System, the Tingitana peninsula. From all these sectors it disappears throughout the decalustro. Thus, in 1950, only the main towns remained in the southwestern quadrant of Spain, with adjacent areas, that is, without fragmenting: Doñana, the western Sierra Morena (small), the Tagus Valley as it passes through the border between Spain and Portugal and through Torrejón. el Rubio, in Extremadura (small), Montes de Toledo and Tiétar valley as it passes through the border of Madrid, next to Ávila.

With the continuation of the decline, in the 1967 census, the first to be carried out, fifty couples were estimated. In this count, the distribution was considered by four nuclei: Sierra de Guadarrama, Monte del Pardo, Tajo valley and Doñana, but a second census in 1974, more precise, corrected this distribution with that observed in the previous paragraph but, evidently (since twenty-five years passed) with the nuclei much smaller, and also fragmented, with only some very small subpopulations remaining next to them, such as that of the Sierra de Béjar.

Thanks to recovery efforts and legal protection provided in 1966, the negative trend was reversed in the 1970s, and by the end of the 1980s the estimated number was one hundred and thirty couples. With this, the existing populations grew and new small nuclei were formed, such as that of the eastern Sierra Morena. However, during the 1990s the evolution of the population was very negative, and compared to the 1989 census there was a 30% decrease in couples. This propensity reverses with the beginning of the new century, and by 2004 there were already one hundred and ninety-five couples.

In 2011 there were three hundred and seventeen pairs, which meant that the old distribution sectors have increased significantly and new subpopulations have been formed. In this way, the western and eastern Sierra Morena have large populations, the population of the Tiétar valley has extended northwards until it penetrates into Castilla y León and covers the mountains north of Madrid, a new nucleus has been born in the southeast of Portugal., and in general the rest of the concentrations have grown, even ceasing to be very little or not at all fragmented (continuing with the Tiétar valley, it has grown in this way thanks to the fact that the subpopulations of Monte del Pardo and Sierra de Guadarrama have also grown. fact, thus uniting the three groups together).

Conservation status

One hundred and ninety-four breeding pairs were censused in Spain (2004) and recently[when?] two pairs have recolonized Portugal. The contingents of the species have maintained a positive growth trend since 1974, date of the first census, until the present. Part of this upward change in the number of individuals could be linked to a greater prospecting effort during the last decade. In 2010, censuses were carried out. two hundred and eighty-two couples: two hundred and seventy-nine in Spain and three in Portugal (Ministry of the Environment, Rural and Marine Environment). BirdLife International, following the IUCN 2001 criteria for red lists, classifies it as Vulnerable (VU), which represents a downgrade since the last review, which considered it Endangered (EN). This change in status is has been promoted by the results obtained in modeling that point to a stabilization of the different subpopulations in the coming years. Despite this positive population trend, it is a species with a very small number of individuals and whose survival is linked to intensive conservation actions.

Among the main causes of threat are mortality from poisons, electrocution and direct human persecution, the scarcity of rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus)—their main prey—, habitat deterioration and fragmentation, pollution and diseases.

At the beginning of the XX century, the Iberian imperial eagle was still a very abundant animal in much of its range. distribution, but in recent decades their number has plummeted. The population of Morocco is considered extinct.

Since 1991, a marked disproportion of sexes has been observed in the population around Doñana, where 70% of the chicks born are males. In 2005, the CSIC launched a plan to try to increase the number of females and solve this problem.

Although it is still in danger, the attention of the Spanish administrations has ensured that despite all the impediments, the population of this symbol of the Iberian fauna has doubled since the beginning of the 1990s. Currently there is a recovery plan for the species at the national level and some of the autonomous communities that host the bird have also developed their own conservation plans.

Contenido relacionado

Bear johnson

Camelidae

Bovine spongiform encephalopathy